Lucky Day by Chuck Tingle Summary, Characters and Themes

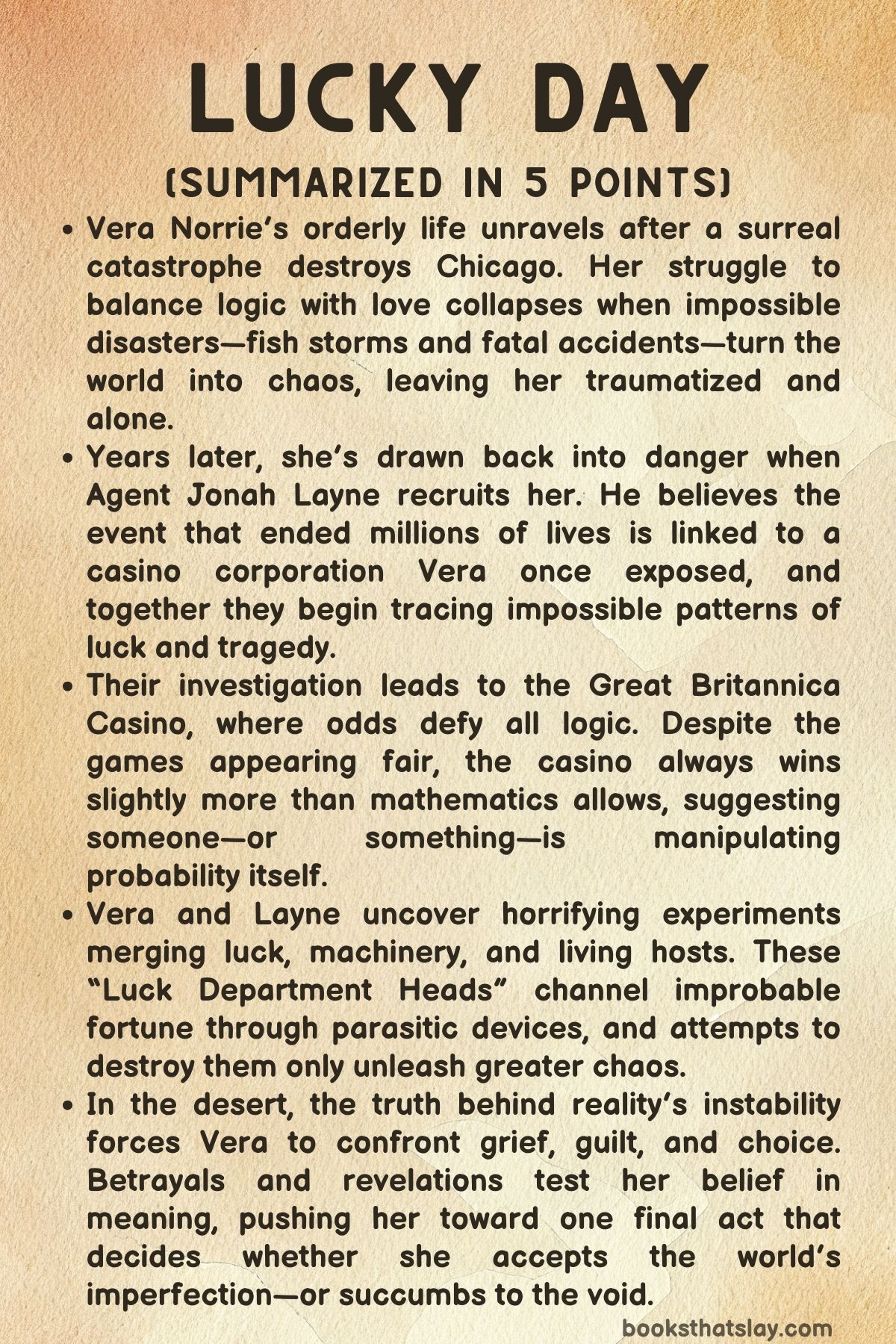

Lucky Day by Chuck Tingle is a surreal speculative thriller that fuses dark humor, existential dread, and tender human emotion into a vivid exploration of probability and chaos. The story follows Vera Norrie, a rational-minded investigator and statistician whose life unravels after a cataclysmic “Low-Probability Event” destroys Chicago.

As she struggles to comprehend the impossible, Vera becomes entangled in a vast conspiracy involving corporate greed, reality tears, and the weaponization of luck itself. Through its strange events, emotional depth, and sharp commentary on control and randomness, Lucky Day becomes both a cosmic mystery and a deeply human story about choice, guilt, and survival.

Summary

Vera Norrie begins her day in Chicago beside her girlfriend Annie, their morning routine shaped by Vera’s obsession with precision and control. Annie, playful and free-spirited, gently teases her partner’s rigid habits as they prepare for Vera’s pre-launch celebration—a brunch marking the release of her nonfiction book on probability and gambling fraud.

Their contrasting personalities—Vera’s logic against Annie’s intuition—are clear when Annie finds a penny from Vera’s birth year marked with a gold star, identical to those Vera once used as a child collector. Annie calls it fate, but Vera rejects superstition, tossing the coin into a fountain.

At brunch, Vera’s friends and mother, Maria, celebrate her professional success. Underneath the laughter, tension builds—Vera intends to come out to her mother.

When she finally reveals that she’s engaged to Annie, Maria reacts with denial and anger, claiming her daughter’s bisexuality is imaginary. The confrontation explodes in public humiliation and heartbreak.

Maria storms out, and Vera, torn between rage and guilt, chases her into the street—only for the world to collapse into chaos. Fish rain from the sky, vehicles crash, and a red truck smashes into a wall, killing Maria instantly.

Within moments, all of Chicago descends into a nightmarish catastrophe: parades of corpses, spontaneous explosions, monstrous apparitions, and impossible deaths. Vera staggers through a hellish landscape as people die in grotesque, improbable ways.

Her friend Kevin is killed by a chimpanzee in a Renaissance costume wielding a typewriter. Vera barely escapes the city, her reality shattered.

Years later, Vera lives in isolation at her mother’s abandoned Wisconsin home. Grief has drained her will to live; she survives mechanically until a stray black cat, whom she names Kat, rekindles faint empathy.

When Kat dies suddenly, Vera’s fragile recovery collapses—until Agent Jonah Layne from the Low-Probability Event Commission (LPEC) appears at her door. He believes the catastrophe that killed millions is connected to Everett Vacation and Entertainment, the corporation Vera once exposed.

Layne offers her a chance to investigate, and for the first time in years, Vera feels a sense of purpose.

Reluctantly partnering with Layne, Vera travels with him to Las Vegas to examine the Great Britannica Casino, owned by Everett Vacation and Entertainment. Layne believes that all victims of the Low-Probability Event had ties to this casino, known for offering gamblers unusually favorable odds.

Vera remains skeptical but intrigued when she learns her late mother might have visited it. The pair meet Denver White, the confident young CEO who runs the casino.

Despite her polished demeanor and insistence that everything is legal, Vera notices subtle anxiety when the company’s real estate holdings are mentioned.

Later, Layne admits he already has the casino’s internal data and wanted to gauge Denver’s reaction. Vera spends days analyzing the files and discovers a statistical impossibility: even though the games favor players, the casino consistently profits slightly above what probability allows.

It’s as if luck itself is being manipulated. Confused and furious at the absence of logical explanation, Vera nearly quits the case.

Layne convinces her to continue, taking her to a trailer park where a “Minor Low-Probability Event” has just occurred. There she witnesses a man whose face has become a swirling black void—a living tear in reality.

Layne explains that such rips, or “plot holes,” spawn bursts of extreme luck and misfortune that eventually balance out. Vera realizes the catastrophe in Chicago was not a one-time event but part of an ongoing breakdown of reality.

The investigation deepens. Layne reveals he lost his brother during the original catastrophe and joined LPEC after discovering another rift that caused simultaneous deaths and impossible good fortune in Nashville.

Vera begins theorizing: what if luck is a real, measurable force that can be transferred or manipulated? The Great Britannica might be harnessing these rips for profit.

Their shared insight forms an uneasy bond as they pursue answers.

When Vera and Layne confront Denver again, she admits that her company’s scientists have been experimenting with devices that channel probability. These devices appear as grotesque centipede-like organisms attached to people’s necks—living conduits of manipulated luck.

One such host, a man named Mark, exhibits twitching movements as the machine maps streams of luck through his body. Denver claims attempts to destroy these parasites resulted in deadly backlashes.

She knows they came from the same “plot holes” connected to the earlier disasters. Layne offers her immunity if she helps them neutralize the devices, though Vera resents letting the guilty go free.

Still, she agrees, understanding that stopping the spread is more urgent than revenge.

Denver arranges for Vera and Layne to reach a remote desert site linked to the corporation’s secret experiments. As they travel at night, strange phenomena erupt: confetti rains from the sky, vehicles fail simultaneously, and monstrous forces attack.

Denver is seized by a pale tendril and vanishes. Layne and Vera flee, taking with them a caged centipede-host from the wreckage.

As they cross the desert, Vera deciphers coordinates tied to the casino’s files, leading them to a hidden bunker.

Inside, the facility is strewn with corpses of guards killed through bizarre chain reactions—slips, stray gunfire, electrocutions—echoing the absurd cruelty of the earlier disaster. A familiar penny with a gold star rolls to Vera’s feet, reminding her of Annie and fate.

In the central chamber stands an enormous, pulsating hole in reality. Layne sets up stabilization equipment while Vera dons a protective suit, taking the caged parasite, and steps into the portal.

Within the void, Vera experiences shifting illusions. The darkness becomes a diner from the day her mother died, where she encounters Maria and old companions who claim she “does not exist.

” The scene mutates into a white gallery where a false version of her mother offers her another caged centipede and tempts her to bring both back—to end reality and embrace oblivion. The void reveals Layne’s past: during the original catastrophe, he was driving with his brother when a falling fish shattered their windshield, killing his sibling and causing the crash that killed Vera’s mother.

The void urges Vera to accept nothingness, but she refuses, remembering her cat, the sunlight, and fleeting love. She leaves the cages behind and escapes.

Vera emerges to find the rift closing. Layne, injured but alive, plans to report to the LPEC.

During the drive back, he draws his gun, revealing that consultants like her are expendable. Vera crashes the car, killing him, and retrieves his hidden USB key.

Using it, she leaks classified files to journalists, exposing the government’s exploitation of “luck” experiments, human testing, and manipulation of probability for corporate gain.

Back in Wisconsin, Vera dismantles her gun, opens her blinds, and watches her yard bloom with flowers growing from her cat’s remains—life returning from decay. She sends a message to Annie, apologizing and asking to talk.

Her phone buzzes as the story closes, suggesting the smallest chance—a new beginning.

Characters

Vera Norrie

Vera Norrie stands at the center of Lucky Day, serving as both the narrator and the emotional axis around which the story’s exploration of fate, probability, and guilt revolves. She is a meticulous, logical woman whose devotion to control stems from a deep-seated fear of chaos.

At the beginning of the novel, Vera’s rigid personality contrasts sharply with the spontaneous warmth of her girlfriend, Annie. Her obsession with order and data—embodied by her career as an investigator and author of a book on gambling fraud—reflects a need to impose structure upon an unpredictable universe.

However, the cataclysmic “Low-Probability Event” shatters her sense of rationality. Through Vera, Chuck Tingle examines how trauma and grief dismantle intellectual certainty.

Years after the disaster, she has become hollow, living in emotional exile. Yet when Agent Layne reintroduces purpose through the investigation, Vera slowly reconnects with her humanity.

Her eventual defiance against the void, and her decision to expose the truth, mark her transformation from a detached observer into a morally awakened survivor. Vera’s journey is thus one of rediscovering meaning in randomness, finding hope amid nihilism, and learning that empathy—not control—is the true antidote to chaos.

Annie

Annie represents the emotional foil to Vera’s calculating nature. She is lighthearted, imaginative, and instinctively spiritual, the kind of person who sees meaning in coincidences.

Her playful optimism contrasts with Vera’s skepticism, yet it also reveals the tenderness that balances their relationship. Annie’s insistence that the found penny is a sign of fate, and her belief in luck’s power, introduce the novel’s thematic tension between probability and faith.

Even though Annie disappears early in the narrative, her presence lingers throughout the story as a haunting reminder of what Vera has lost—not only love but also trust in the unknowable. Annie embodies the possibility of wonder, the belief that meaning can exist without proof.

When Vera finally reaches out to her again at the end, Annie’s symbolic role as hope’s anchor is restored. She represents the emotional continuity that survives even when logic and order collapse.

Maria Norrie

Maria, Vera’s mother, personifies generational conflict and the weight of denial. A woman shaped by traditional expectations, she struggles to accept her daughter’s sexuality and independence.

Her reaction to Vera’s coming out—anger, disbelief, and prejudice—exposes the limits of love constrained by rigid morality. Yet Maria’s characterization extends beyond intolerance; she reflects the tragedy of misunderstanding between parent and child.

Her death during the raining-fish catastrophe transforms her from antagonist to martyr of chance, embodying the cruel indifference of fate. Vera’s guilt over their unresolved relationship becomes one of the novel’s central emotional wounds.

Through Maria, Lucky Day explores how human connections, strained by misunderstanding, can be abruptly severed by randomness. Her spectral presence later in the void sequence shows how grief distorts memory and how forgiveness becomes both impossible and necessary.

Agent Jonah Layne

Agent Layne of the Low-Probability Event Commission is a paradoxical character—both a comic relief and a moral catalyst. Cheerful, eccentric, and occasionally irritating, Layne initially seems like the narrative’s optimist to Vera’s cynic.

However, his quirkiness conceals a deep trauma: the death of his brother during the original Low-Probability Event. This duality makes Layne more than just a foil; he is a mirror for Vera, equally haunted by survivor’s guilt yet channeling it into action.

His belief in the supernatural mechanics of probability contrasts with Vera’s analytical skepticism, but their collaboration slowly merges intuition with intellect. Layne’s ultimate betrayal—attempting to kill Vera to protect bureaucratic secrecy—reveals the corruption of institutions that claim to manage chaos.

Yet even in death, Layne’s complexity endures. His role underscores how idealism can curdle into complicity when bound to systems of control.

Denver White

Denver White, the young CEO of the Great Britannica casino, embodies the seductive face of corporate amorality. Charismatic, brilliant, and disturbingly composed, she thrives on the manipulation of chance.

To her, probability is not a field of study but a commodity to be engineered and sold. Denver’s interactions with Vera and Layne blur the line between villainy and pragmatism; she is neither overtly malicious nor sympathetic but chillingly self-assured.

Her revelation of the centipede-like devices that channel luck exposes the dehumanizing machinery beneath capitalist spectacle. Denver’s death—encased and suffocated by an alien shell—serves as grotesque poetic justice, transforming her into another victim of the system she exploited.

Through her, the novel critiques the monetization of chance and the illusion of control perpetuated by corporate power.

Kat

Kat, the stray black cat Vera adopts in her isolated years, may seem minor but plays a crucial symbolic role. The cat becomes a vessel for Vera’s tentative return to emotional life after years of numbness.

In caring for Kat, Vera reconnects with the rhythms of empathy, responsibility, and affection—elements lost since the catastrophe. Kat’s sudden death devastates her, representing the fragility of renewed hope, yet its skeletal remains later nurture flowers in Vera’s garden.

This image transforms Kat into a symbol of regeneration and continuity, illustrating that even death can feed new life. In a novel preoccupied with the absurd cruelty of chance, Kat embodies the quiet resilience of nature and the persistence of care.

Themes

Probability, Control, and the Illusion of Order

In Lucky Day, the relationship between probability and control becomes the narrative’s intellectual and emotional axis. Vera, a scholar of probability and a woman obsessed with predictability, builds her life around structure—schedules, measured speech, and empirical certainty.

Her academic work on gambling fraud mirrors her psychological need to prove that randomness can be contained through logic. Yet as the world collapses into statistical chaos during the Low-Probability Event, Vera’s framework for understanding reality disintegrates.

The improbable becomes omnipresent: fish rain from the sky, planes collide, and people die through impossible coincidences. These moments mock the idea of control, turning probability—the language Vera once mastered—into an incomprehensible force.

The novel uses this collapse to critique the human compulsion to rationalize existence, exposing how reason can serve as both shield and shackle. The illusion of order comforts Vera until it traps her, making her incapable of recognizing or accepting unpredictability as an essential condition of life.

When she eventually faces the literal rifts in reality, the “plot holes,” she confronts the same truth on a cosmic scale: that order is fragile, and that life persists not through logic but through resilience within chaos. Chuck Tingle transforms probability from a mathematical abstraction into a philosophical question—whether humanity’s pursuit of order is a noble defense against meaninglessness or merely a refusal to face it.

Trauma, Guilt, and the Weight of Survival

The emotional core of Lucky Day lies in Vera’s survival and the guilt that follows. Her mother’s death during the catastrophe becomes both a haunting memory and a moral burden.

The randomness of her survival feels punitive, not lucky—she lives while others die without reason. Her later life in isolation, surrounded by silence and decay, reflects the paralysis of trauma, where survival feels like a cosmic mistake rather than a gift.

The black cat that momentarily rekindles her empathy represents a tentative bridge between detachment and life, yet its death reinforces the cycle of loss that defines her existence. Through Vera’s perspective, Tingle explores the corrosive effects of guilt, showing how survivors often internalize chaos as personal failure.

Even when Vera is recruited to investigate the catastrophe’s origins, her motivations are less about justice than the desperate need to give her pain structure—to transform meaningless tragedy into solvable mystery. The novel gradually reframes survival not as a debt to be repaid but as a quiet act of defiance.

By the end, when Vera accepts life’s contradictions and opens herself to reconciliation, her endurance becomes a reclamation of agency. Her choice to live, not simply exist, redefines survival as the courage to embrace imperfection rather than the burden of explaining it.

Corruption, Exploitation, and the Ethics of Chance

The corporate machinery behind Everett Vacation and Entertainment functions as a cynical extension of human greed—an entity manipulating luck itself to preserve power. In Lucky Day, the casino and its parasitic “luck devices” literalize how systems exploit chance and human vulnerability for profit.

The company’s control of probability is a perverse mirror of capitalism’s manipulation of risk: games appear fair, outcomes seem random, yet the house always wins. This imbalance becomes an allegory for exploitation disguised as opportunity, where even fortune is commodified.

The Luck Department, with its grotesque centipede-machines and enslaved “hosts,” embodies the dehumanization of those consumed by corporate control. Through Vera’s moral outrage and Layne’s pragmatic cynicism, Tingle interrogates complicity—how institutions justify cruelty through statistics and how individuals rationalize moral surrender in the name of greater stability.

When Vera leaks the classified data, her rebellion is both personal and systemic: a rejection of power structures that weaponize probability and treat people as expendable variables. The theme exposes the ethical decay that arises when randomness—once a neutral aspect of existence—is harnessed as a tool for dominance.

By the conclusion, Tingle frames corruption not as an aberration but as a distortion of the same human desire for control that drives Vera herself, linking the personal to the political in unsettling symmetry.

Reality, Existence, and the Temptation of Oblivion

Throughout Lucky Day, reality is neither stable nor trustworthy. The “plot holes” and probability tears are physical manifestations of existential uncertainty—the places where meaning collapses under contradiction.

Vera’s journey into the void literalizes her confrontation with nihilism, culminating in a vision where the universe tempts her to surrender to nothingness. The void’s logic is seductive: if reality is arbitrary and cruel, nonexistence offers purity and relief.

The novel uses this confrontation to examine humanity’s craving for meaning even when evidence of order disappears. Vera’s refusal of the void, grounded in her memory of her cat and her human connections, becomes a philosophical stand against despair.

It is not reason or faith that saves her but the recognition that small, flawed attachments give life coherence amid senselessness. This affirmation transforms her understanding of existence from something to be decoded into something to be inhabited.

Tingle suggests that meaning is not discovered but created in defiance of entropy. The final image—flowers blooming from death, life continuing despite absurdity—captures this transformation.

Reality remains unstable, but Vera’s acceptance of its messiness becomes an act of creation itself, asserting that imperfection and chaos are not proof of futility but evidence of life’s persistence.

Love, Identity, and Reconciliation

The evolution of Vera’s relationships, particularly with Annie and her mother, grounds Lucky Day in deeply human conflict amid its surreal chaos. Vera’s difficulty expressing love stems from her fear of vulnerability—a need for control that mirrors her obsession with probability.

Her mother’s denial of her sexuality intensifies this fear, binding love to shame and rejection. The apocalyptic collapse that follows their argument externalizes this emotional fracture: the world literally falls apart as Vera’s personal world implodes.

Her long estrangement and eventual message to Annie years later signify a journey toward reconciliation not only with others but with herself. Through love, Tingle presents identity as an act of truth-telling, a confrontation with the self unmediated by logic or justification.

Vera’s queerness, initially suppressed by familial expectation and internalized rationalism, becomes inseparable from her moral awakening. By embracing love after witnessing horror and betrayal, she reclaims her identity as something resilient rather than fragile.

The final scene—Vera choosing sunlight, growth, and connection—reframes love as both defiance and redemption. It asserts that even in a world where logic fails and probability fractures, love endures as the most authentic proof of existence.