Moderation by Elaine Castillo Summary, Characters and Themes

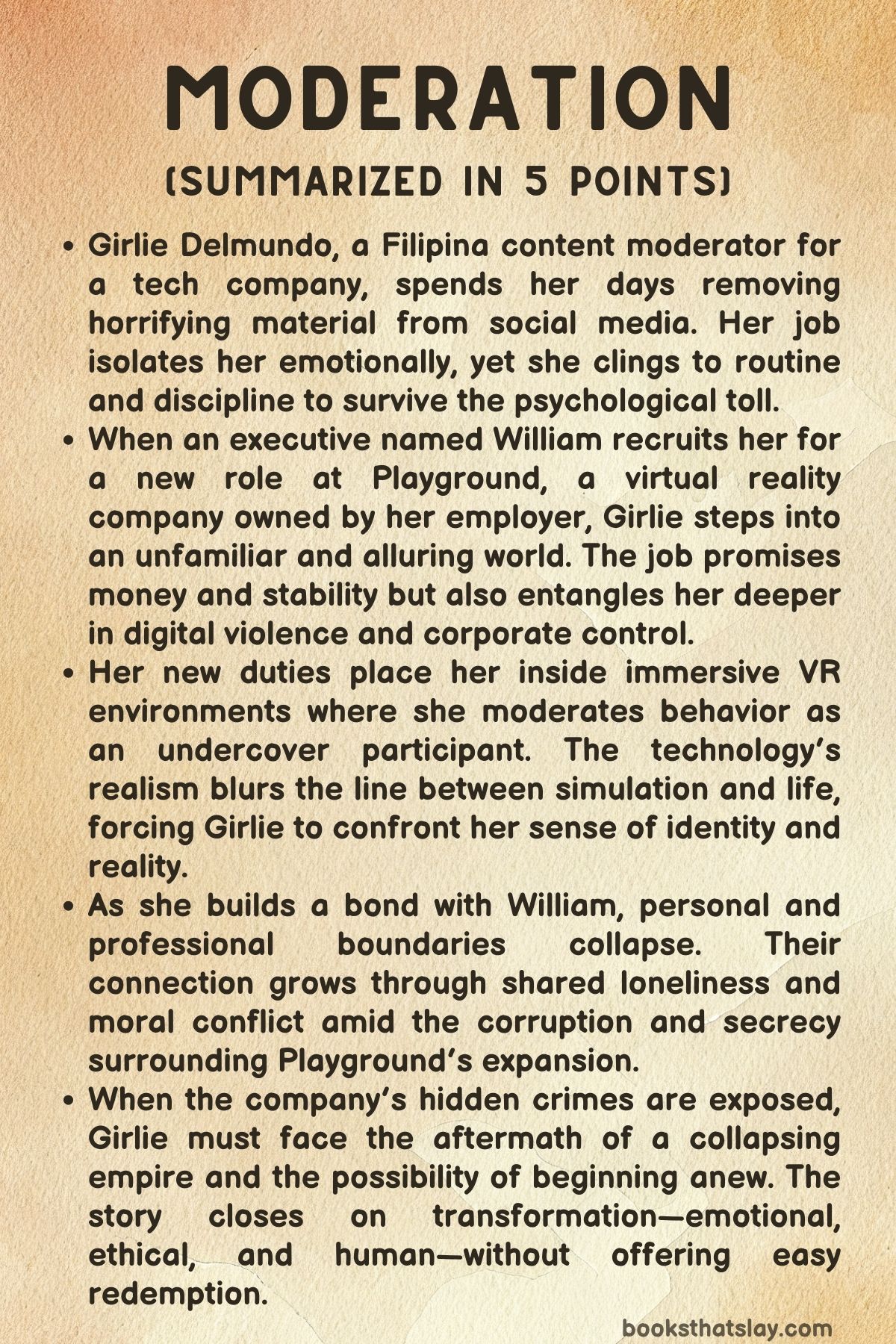

Moderation by Elaine Castillo is a haunting examination of the hidden labor behind digital safety and the psychological toll of moderating humanity’s darkest impulses. The novel follows Girlie Delmundo, a Filipina content moderator working for a social media contractor in Las Vegas, who spends her days filtering violent and abusive imagery from online platforms.

When a new opportunity arises at a virtual reality company, she is drawn into an even more immersive—and ethically fraught—world where reality and simulation blur. Through Girlie’s story, Castillo explores technology’s exploitation of emotion, migrant labor, and the fragile borders of selfhood in an increasingly digital age.

Summary

Girlie Delmundo works for Reeden, a company tasked with cleansing social media of violent and explicit content. Over the years, she has become one of the few long-term survivors in a job notorious for its psychological damage.

What was once dominated by white American workers is now largely staffed by Filipina women—seen as disciplined, compliant, and fluent in English. Girlie excels at identifying child exploitation material, her composure masking the deep fatigue that defines her existence.

Her daily routine revolves around a sterile office filled with motivational posters and meaningless wellness programs meant to disguise the trauma inherent in their labor. She copes through routine—strict diet, weightlifting, and avoidance of intimacy—while sustaining her extended family financially.

At home in Las Vegas, Girlie lives with her mother and cousins in a house once bought during the housing boom, later nearly lost during the 2008 crash. The house stands as both a relic of immigrant ambition and a reminder of financial fragility.

Girlie’s cousin Maribel works as a bartender and dreams of a more open life. When Maribel decides to propose to her girlfriend Avery at her upcoming birthday party, Girlie takes on the planning despite her misgivings.

Beneath her calm exterior, Girlie struggles with loneliness and detachment, occasionally scrolling through real estate listings of the Bay Area home her family lost years before—a digital haunt of her former life.

Her monotonous existence shifts when corporate executives visit her moderation site. Among them is William Cheung, a poised and enigmatic representative from Playground, a virtual reality company recently merged with Reeden and a French entertainment firm called L’Olifant.

Impressed by her work, William offers Girlie a promotion to a new position—“active moderation” inside virtual environments. Though wary, she meets him for dinner to learn more.

Over a polished meal, William outlines Playground’s transformation from a therapeutic VR experiment into a massive entertainment empire. The offer is extraordinary: full-time employment, stock options, and a life-changing salary.

Girlie, stunned, accepts an invitation to tour the Playground facility.

The next day, William introduces her to the company’s futuristic offices, far removed from the grim moderation floor below. He equips her with an advanced VR bodysuit and guides her through a simulation of a grand historical fairground—a world of palaces, amphitheaters, and oceans of avatars.

The detail and beauty of the environment are overwhelming. William explains that moderators will now operate inside such spaces, disguised as ordinary users, policing content and behavior from within.

The boundary between human labor and digital surveillance has collapsed. Girlie accepts the role, aware that she’s entering a new phase of exploitation but drawn by the promise of escape.

Girlie’s training at Playground is rigorous and isolating. She learns to navigate immersive landscapes, manage in-world crises, and suppress emotional reactions to virtual violence.

The new system maps her body for a second-skin suit, embedding her identity deeper into the machine. As she adapts, she encounters William in both physical and virtual settings—their relationship oscillates between mentorship and subtle intimacy.

One day inside a Roman simulation, they share a moment of quiet connection before being interrupted by a violent avatar. Girlie senses that their bond exists in a space neither fully real nor artificial.

Therapy sessions with Dr. Perera, the company psychologist, become a refuge.

During one, Girlie admits she wants to learn to swim—a skill tied to childhood trauma. Perera designs a VR program to teach her, guiding her through simulated beaches and oceans.

The sessions become metaphors for control and surrender; she learns to “float” by relinquishing fear. Her progress mirrors her growing ability to navigate the emotional currents of both real and virtual worlds.

Meanwhile, the company expands aggressively. During Playground’s launch gala at the Bellagio, Girlie endures a night of corporate spectacle and performative optimism.

To her horror, she runs into Maribel, who is working the event as a server, blurring the boundaries between Girlie’s private and professional lives. William meets Maribel and, in an awkward moment, is invited to her upcoming birthday celebration.

The evening spirals when Girlie thinks she sees a man from a traumatic moderation case among the guests. She chases him through the crowd, only for William to stop her, realizing she’s hallucinating figures from the past.

The visions have followed her for years—a symptom of the endless exposure to digital horror. He is shaken by her calm acceptance of it.

Weeks later, virtual assaults in Playground’s simulations increase, echoing the chaos of the real internet. Girlie continues to moderate violence from within, aware of the futility of control.

She and William grow closer, sharing quiet moments in the virtual Trevi Fountain and later in a bar, where he tells her about Edison Lau, Playground’s founder. Edison’s obsession with realism drove him to reconstruct personal memories so precisely that they overrode reality itself.

His ambition and depression led to his death—possibly a suicide—after Reeden’s corporate takeover. William reveals that he inherited Edison’s dog, Mona, and carries the guilt of having failed him.

Their conversation exposes shared grief and longing, but when intimacy threatens to surface, Girlie retreats again.

The corporate empire soon begins to unravel. Dr. Perera confides that Reeden has corrupted Edison’s therapeutic technology into a massive data-harvesting system, blending medical experimentation with entertainment. Lawsuits and investigations erupt, exposing Reeden and L’Olifant’s illegal surveillance and exploitation of users.

As the company collapses, Girlie returns to an almost deserted office. Logging into the system, she finds herself inside one of Edison’s creations—a virtual fairground haunted by fragments of history.

There, she meets a digital version of William, who reveals he’s leaked evidence of the corporation’s crimes and that the avatar she’s speaking to is only a recorded copy of himself. His actions have destroyed Reeden and cost him everything.

He tells her she’s been laid off, her contract terminated with severance.

In the fading simulation, Girlie refuses to believe he’s gone. She insists that he exists somewhere beyond the code.

When he admits he’s in London’s Crystal Palace, their final exchange turns tender and desperate—they share a last kiss before the program shuts down. In the real world, Girlie discovers that Dr. Perera protected her personal data from corporate use. With quiet resolve, she liquidates her savings, helps her family financially, and decides to leave the United States behind.

Girlie relocates to London, renting a small flat in Crystal Palace. Life there is muted but freeing—she wanders through parks, museums, and markets, beginning to rediscover her autonomy.

One afternoon, she unexpectedly encounters William and his dog at a café. Both are stunned but relieved to see each other alive.

They talk about the company’s downfall, their past colleagues, and the strange aftermath of their shared experiences. Their humor returns, softer and more human than before.

When William asks why she’s come to London, she says she’s trying to change her life. As they walk away together, Girlie tells him her real name for the first time.

In that moment, the boundaries between identities—employee, moderator, avatar, survivor—finally dissolve. Together, they step into an uncertain but tangible world, no longer governed by screens or simulations, but by the fragile truth of their shared humanity.

Characters

Girlie Delmundo

Girlie is the novel’s central consciousness, a Filipina content moderator whose survivalist discipline masks profound vulnerability. In Moderation, she is forged by exposure to humanity’s worst images and by the racialized labor pipeline that funnels resilient, obedient, English-fluent Filipina women into invisible digital sanitation.

She creates a hard carapace—weights, diet, punctuality, refusal of faux-wellness—yet her body betrays her with phantom smells and panic; trauma leaks through in the very senses her job tries to deaden. She is also the family’s ballast, underwriting a multigenerational mortgage while guarding a private sorrow over the lost Milpitas home, which she stalks on Zillow like a ghost of a life that might have been.

Her alias, chosen to separate work-self from family-self, becomes a fragile shield against psychic corrosion. When William recruits her into VR “active moderation,” she crosses from watching atrocity on screens to policing it from within immersive worlds.

The upgrade in status and pay appears to offer restitution for years of precarity, but the deeper arc is ethical and existential: Girlie is compelled to ask whether safety and order in synthetic empires can ever be clean when built on extraction—of labor, of data, of memory. Her late migration to London, the swimming lessons, the unlearning of fear, and the willingness to speak her true name mark a rebirth that does not cancel her past so much as metabolize it; she learns to float by surrendering, not by stiffening.

William Cheung

William is Girlie’s counterpart and catalyst: a polished, weary insider who believes in craft, realism, and care while operating within corporate machinery that rewards spectacle and control. In Moderation, he reads at first as a recruiter—Reverso on wrist, gentility in manner—but the veneer covers grief and complicity.

Loyal to Edison and Mona, he shepherds Playground’s evolution from therapeutic realism to grand, monetized lobbies, then turns whistleblower when that dream curdles into exploitation. His attraction to Girlie begins in professional regard—her composure, her medieval French, her eye for pattern—and deepens into a mutual recognition of loneliness and rigor.

He is simultaneously the man who ushers her into total immersion and the man who yanks the plug on the empire, leaving her jobless yet freer. The recording he leaves in the Fairground, equal parts confession and farewell, reframes him not as corporate savior but as someone trying, clumsily and bravely, to choose the human over the machinic.

Meeting Girlie again in Crystal Palace, stripped of status and sleep, he finally allows tenderness to stand without strategy.

Maribel

Maribel, Girlie’s younger cousin, embodies exuberant risk and the ache for public joy. In Moderation, her Vegas hustle—bartending, plotting a terrace proposal, evangelizing queer spectacle—clashes with Girlie’s suspicion of coercive grand gestures, revealing a loving but asymmetrical dynamic: Girlie manages logistics and shields the family from fallout; Maribel insists on visible life.

Her relationship with Avery and her easy warmth with William at the birthday party show a gift for bridging worlds that Girlie treats with caution. When Girlie quietly gives her money and permission to start anew, Maribel becomes the figure who receives what Girlie never had: a chance to launch without self-annihilation.

Their parting is one of the book’s tender truths—care that releases rather than binds.

Flo

Flo, Girlie’s mother, is the lineage of sacrifice that underwrites the novel’s economy of care. A nurse who chased the American home-ownership dream across state lines, she loses almost everything in the crash, then folds into the Las Vegas household where pride and debt coexist.

In Moderation, Flo’s nagging about marriage and children comes freighted with class fear and immigrant math; every life choice is a mortgage calculation. Her presence explains Girlie’s double bind: the drive to provide and the refusal to be consumed.

Even when offstage, Flo’s needs structure Girlie’s choices—bus rides instead of the Tesla, extra shifts instead of dates—until Girlie’s departure to London reframes care as something possible from a distance, no longer tethered to the moderator floor.

Dr. Perera

Perera is the hinge between therapy and technology, the clinician who uses VR to retrain bodies and nervous systems. In Moderation, he guides Girlie through breathing, buoyancy, and the terror of submerging her face—small acts that reroute a life habituated to bracing.

His ethical unrest grows as corporate interests cannibalize therapeutic tools for data and profit; warning Girlie to safeguard herself, he becomes a rare adult in a room of executives playing civilization. His decision to keep her biometrics out of the machine is a quiet act of resistance that grants her an intact self to carry into the book’s final movement.

Edison Lau

Edison is the haunted origin of Playground’s realism: an artist-engineer who wants VR to rebuild trust in memory with such fidelity that the brain yields. In Moderation, his stubborn insistence on accuracy over scale produces wonders that investors cannot monetize, and grief that he cannot escape; reenactments of childhood and a collapsing mind make him both visionary and warning.

His ambiguous death—fall, jump, push—becomes the moral spur for William’s exposure of corporate rot. Edison’s dream survives only in the restorative uses Girlie finds for immersion—learning to swim, relearning her body—gestures that honor his better intentions while refusing his self-erasure.

Aditya

Aditya personifies the smooth escalation of ambition within extractive systems. In Moderation, he escorts investors through sanitized floors, translates cruelty into OKRs, and romances the glamour of the launch even as moderators absorb the blows.

His rumored entanglement with Vuthy humanizes him without absolving him. He can admire Girlie’s competence and still place her in harm’s way, a contradiction the novel insists we recognize in modern management: pleasant, promotive, proximate to harm.

Joseph

Joseph, the floor manager, is the banal face of containment. In Moderation, he keeps throughput high, cycles bodies in and out, and outsources care to cake and symposiums.

His role clarifies that violence in platform economies is not only what users do on screens but how organizations metabolize workers—cheerfully, efficiently, replaceably.

Jess

Jess is the new hire who cannot “get used to it. ” In Moderation, her panic inside VR, refusal to log out, and collapse into resignation dramatize what Girlie long ago learned to suppress.

Jess’s crisis is also Girlie’s mirror; by sprinting through real corridors to reach her, Girlie briefly exits the logic of metrics and latency, reentering the human tempo of touch, voice, consent. Jess reminds us that breaking is a kind of knowledge.

Vuthy

Vuthy exists at the edges of executive spaces—competent, alert, and entangled with Aditya. In Moderation, he helps stage the illusion that the empire is stable while absorbing the same precarity as other moderators.

His presence underscores the book’s attention to diasporic workers who keep the lights on yet remain outside the frame of credit and ownership.

Avery

Avery, Maribel’s partner, is love under strain: sick, hopeful, the imagined recipient of a terrace-top proposal. In Moderation, she represents what public joy tries to secure against illness, work, and money.

Through Avery, the novel refuses to separate romance from the economic and bodily contingencies that shape queer domesticity.

Sam

Sam, Girlie’s former girlfriend, appears in crisp retail light—Tiffany blue as corporate glass. In Moderation, that brief, clipped encounter hints at Girlie’s history of intimacy constrained by time, money, and secrecy.

Sam’s composure contrasts with the underground life of moderation, suggesting why past relationships might have buckled under Girlie’s compartmentalization.

Martin

Martin, the soldier cousin, threads violence across spheres: combat simulations at Playground and the United States’ military imaginary that those simulations aestheticize. In Moderation, his presence makes explicit what the VR arenas often displace—that empire is not only a game skin but a career path, a family story, a wound that returns home.

Maurice de Coligny

Maurice is the theatrical CEO who sells conquest as culture. In Moderation, his speeches convert L’Olifant’s theme-park historicism into a humanist veneer for surveillance and extraction.

He is the book’s satiric monarch, proof that the most dangerous avatars are the ones in suits.

Mona

Mona, the senior dog, is the book’s unexpected truth-tester. In Moderation, she holds William to routines of tenderness, appears as an avatar in the Fairground to guide Girlie, and pads between the two at the close like a benign psychopomp.

Where VR manufactures presence, Mona guarantees it; the animal’s unprogrammed needs anchor both characters to a world that cannot be spun up or patched.

Stella

Stella, Girlie’s aunt and the recipient of the house transfer that kept the family afloat, personifies the compromises that stabilize immigrant kin networks. In Moderation, her family’s occupancy of the McMansion is both haven and reminder of dispossession, a living archive of the risks Girlie keeps paying down.

Themes

The Commodification of Trauma and Digital Labor

In Moderation, Elaine Castillo exposes the brutal economy of digital labor that thrives on the invisible suffering of workers like Girlie Delmundo. The novel lays bare how trauma becomes a commodity in the global tech ecosystem—processed, sanitized, and monetized through the work of content moderators who must repeatedly encounter humanity’s most depraved acts for the sake of “community safety.

” Girlie’s job at Reeden encapsulates the paradox of modern moderation: she must absorb horror to maintain the illusion of online civility. Castillo presents moderation not as a neutral or technical process but as a form of psychic violence outsourced to marginalized workers.

Filipina women like Girlie become the preferred labor force because of their endurance, obedience, and fluency in English—qualities that corporations exploit under the guise of resilience. The daily exposure to disturbing content creates a psychological corrosion so deep that wellness seminars and motivational slogans become cruel jokes.

The novel shows that such corporate gestures merely conceal the truth—that this work destroys people. Even Girlie’s physical routines, her obsessive fitness and self-discipline, emerge as coping mechanisms to maintain control in a job that strips away identity and emotion.

Her phantom smell of smoke symbolizes this lingering contamination—the mind’s attempt to process the invisible burns of constant exposure. By situating Girlie’s labor in Las Vegas, a city defined by artificiality and performance, Castillo underscores the commodification of both trauma and emotion, showing how human suffering itself becomes a spectacle, curated and contained for digital consumption.

Alienation and the Fragmented Self

Girlie’s life unfolds under the shadow of alienation—psychological, cultural, and technological. Her work as a moderator severs her from ordinary social life, forcing her to create boundaries between her professional and personal selves that ultimately fracture her identity.

The pseudonym “Girlie Delmundo” is not merely a company safeguard; it becomes an existential mask, an invented self meant to endure what her real one cannot. Her detachment from family and friends stems from this need for control—a defense mechanism against emotional collapse.

Castillo portrays Girlie’s alienation as emblematic of a larger human condition shaped by technology: the more we connect digitally, the more fragmented we become. The transition from moderating flat screens to navigating virtual reality intensifies this schism.

In Playground’s immersive environments, Girlie’s body is literally split between worlds; she exists simultaneously as flesh and avatar, both moderator and participant. The sensory precision of VR makes alienation more insidious—by feeling so real, it erodes the distinction between authenticity and simulation.

Even her budding intimacy with William reflects this duality; their connection oscillates between genuine tenderness and the eerie unreality of mediated emotion. By the end, Girlie’s attempt to rebuild her life in London suggests a partial recovery—a return to the unaugmented self—but the novel leaves open whether such wholeness is possible after so much fragmentation.

Castillo suggests that modern existence, especially for those caught in digital labor systems, is defined by this oscillation between self-erasure and self-reclamation.

Technology, Ethics, and the Collapse of Reality

Castillo uses the corporate empire of Reeden and Playground to explore how technological innovation corrodes moral and perceptual boundaries. The novel questions not just what technology can create but what it destroys in its pursuit of progress.

Playground begins as a therapeutic venture—a humane attempt to use VR for healing—but gradually mutates into a vast commercial machine that blurs therapy, surveillance, and entertainment. The company’s rhetoric of “safety” and “community” masks a system built on exploitation, data extraction, and psychological manipulation.

Through William’s and Edison’s stories, Castillo reveals the moral rot at the core of technological utopianism: idealists consumed by their inventions, unable to distinguish creation from obsession. For Girlie, the ethical collapse manifests through her work—policing violence within virtual worlds that themselves are designed to simulate violence.

The moderators’ presence inside these simulations becomes paradoxical: they are tasked with maintaining order in systems structured around chaos. When virtual assaults and harassment begin to mirror real-world trauma, the distinction between digital and physical harm disintegrates.

The novel’s climax—William’s data leak and the ensuing corporate implosion—marks not a triumph of justice but a grim reckoning. Reality itself becomes unstable, manipulated through code, memory, and desire.

In the end, Castillo poses a haunting question: when technology can recreate every sensation and memory, what remains real? Moderation becomes not just a story about the ethics of work but a meditation on the vanishing line between reality and simulation.

Migration, Class, and the Inheritance of Survival

Embedded within Girlie’s story is a powerful examination of class and migration, tracing how the legacies of economic displacement shape individual identity. The Filipino diaspora, represented through Girlie’s family, forms the backbone of the novel’s critique of global capitalism.

Their pursuit of stability—buying homes, sending remittances, taking contract jobs abroad—mirrors the very logic of exploitation that sustains companies like Reeden. The 2008 housing crash that ruins Girlie’s family serves as both literal and symbolic loss: a collapse of the American dream built on borrowed money and invisible labor.

Girlie’s job as a content moderator continues this lineage of precarious work, replacing physical care labor with emotional endurance. Her family’s collective migration from California to Nevada signifies both survival and stagnation—upward mobility that leads nowhere.

Castillo highlights how racialized labor persists in new forms, shifting from hospitals and care homes to the digital sphere. The novel also interrogates generational expectations: Girlie’s mother’s sacrifices as a nurse contrast with Girlie’s alienation as a digital worker.

Both women perform unseen labor for others’ comfort. Yet, while her mother’s labor nurtured bodies, Girlie’s labor sanitizes minds.

In this inversion lies the tragedy of modern migration—the transformation of care into control, service into surveillance. The ending, with Girlie’s quiet life in London, suggests a cyclical migration pattern, an unending search for belonging that transcends geography.

Castillo captures how survival itself becomes the inheritance of the working class: endurance mistaken for empowerment, displacement mistaken for progress.

Intimacy, Desire, and the Possibility of Connection

Amid its critique of labor and technology, Moderation unfolds as a deeply human story about desire and the search for connection. Girlie’s guarded existence is punctured by her growing intimacy with William, whose presence unsettles the emotional walls she has built.

Their relationship resists easy categorization—it is part mentorship, part companionship, part love affair haunted by mutual damage. Both characters are marked by grief and professional detachment, drawn to each other precisely because they recognize the loneliness in the other.

Castillo renders their intimacy as an act of defiance against dehumanization; in a world that commodifies feeling, genuine emotion becomes radical. Yet, the novel never romanticizes this connection.

Their bond is shadowed by ethical tension—he is her superior, she his subordinate—and by the haunting question of whether real intimacy can exist when mediated through systems of control. The virtual kiss they share before the company’s collapse blurs the boundaries between affection and simulation, authenticity and artifice.

When they reunite in London, their recognition of each other feels like a reclamation of the real after years of artificiality. The final moment, when Girlie shares her true name, signifies a return to vulnerability—the courage to be seen.

Through this fragile connection, Castillo offers a glimpse of redemption: that amid systemic exploitation and digital alienation, love—however uncertain—remains one of the last human truths.