Mrs Endicott’s Splendid Adventure Summary, Characters and Themes

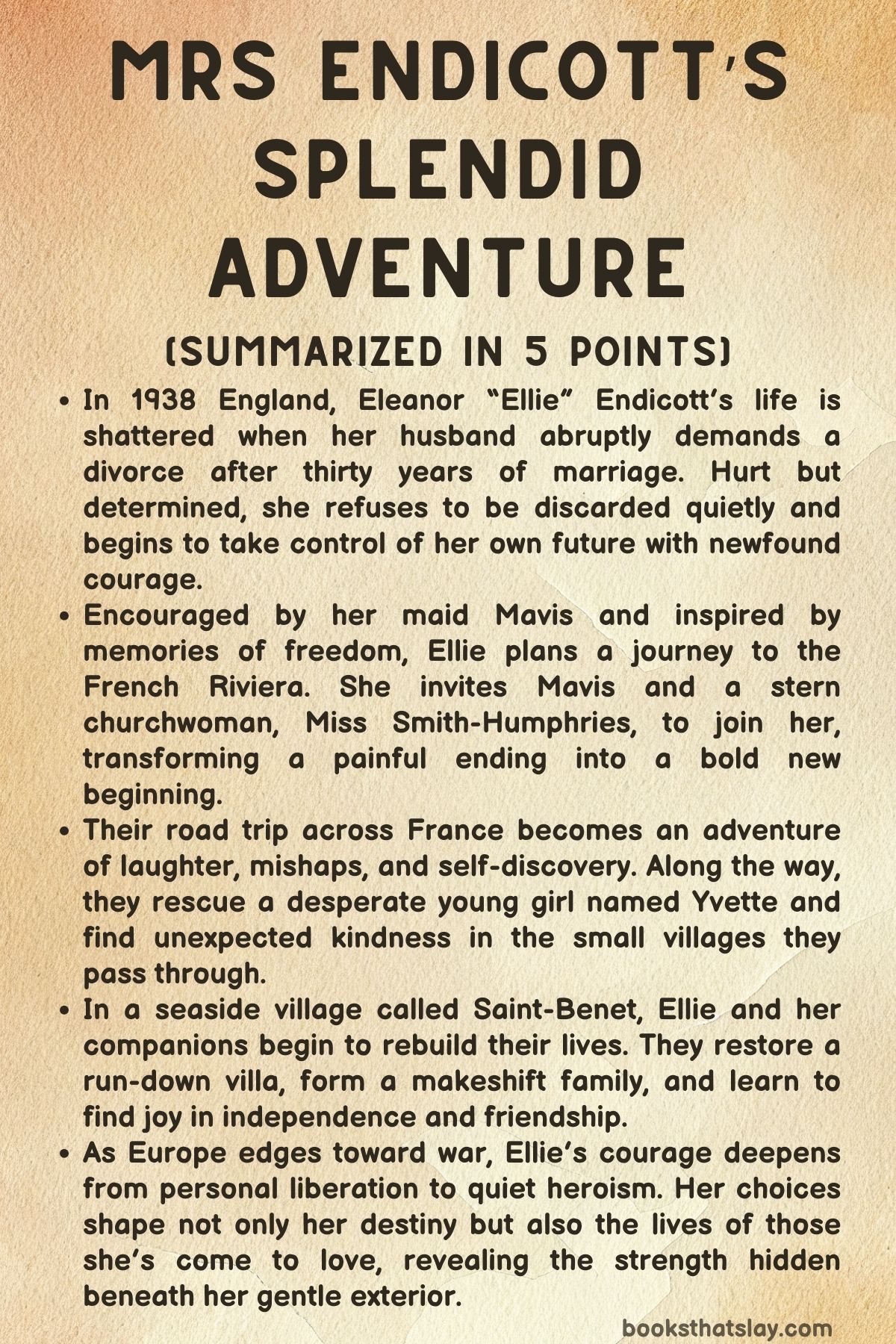

Mrs Endicott’s Splendid Adventure by Rhys Bowen is a historical novel set against the uneasy calm of pre-war Europe. It follows Eleanor “Ellie” Endicott, a conventional Englishwoman whose life unravels when her husband abruptly demands a divorce after thirty years of marriage.

Pushed out of her comfortable existence, Ellie unexpectedly discovers independence and courage. What begins as an impulsive trip to France with two unlikely companions transforms into a story of reinvention, friendship, and resilience. As war clouds gather, Ellie’s journey from a subdued wife to a brave, self-reliant woman mirrors the larger spirit of ordinary people facing extraordinary times.

Summary

In 1938 Surrey, Eleanor “Ellie” Endicott’s life collapses when her husband Lionel, a successful banker, announces over breakfast that he wants a divorce. After three decades of dutiful domesticity, she is stunned to learn that he intends to marry a younger colleague.

Lionel’s cold practicality in suggesting she move into his London flat fuels Ellie’s anger and humiliation. Urged by her loyal maid Mavis Moss to seek legal advice, Ellie meets a local solicitor who encourages her to stand firm.

When Lionel later tries to dictate the terms of separation, Ellie surprises him by confidently negotiating better terms, marking the first step in reclaiming her sense of power.

Lonely yet liberated, Ellie realizes she no longer wishes to remain in the stifling village where everyone will pity her. Remembering her adventurous Aunt Louisa, she decides to journey to the French Riviera—a bold and shocking decision for a woman of her age and background.

Her resolve hardens when Lionel mocks her plan. Encouraged by Mavis, who is trapped in an abusive marriage, Ellie invites her along, offering safety and companionship.

An unexpected addition joins them—Miss Theodora Smith-Humphries, a stern churchwoman with a terminal illness who longs for one last adventure. The three women set off for France in Lionel’s Bentley, with Ellie leaving behind her old life and even her wedding ring.

On the ferry to Calais, the group’s excitement mingles with fear of the unknown. Once in France, Ellie confidently handles border officials, posing Mavis as her maid and Dora as her aunt.

Their laughter over the deception sets the tone for their growing friendship. Traveling through the French countryside, they find joy in small discoveries—food, music, and local hospitality.

In Burgundy, they stumble upon a harvest festival, joining the villagers for dancing and wine. Ellie feels a sense of vitality she hasn’t known in years.

As they drive south, Ellie’s leadership grows. When they nearly run out of petrol near Lyon, she stops at a small garage where she encounters Yvette, a frightened teenager hiding from a predatory lorry driver.

Acting instinctively, Ellie hides the girl and drives off, saving her from danger. Though Dora disapproves, Ellie insists she could not have done otherwise.

Yvette reveals she fled her father’s farm to escape an arranged marriage, and Ellie offers her refuge. The group now becomes four, bound by chance and compassion.

In Valence, Yvette confesses she is pregnant by a soldier and fears rejection. Ellie reassures her, though Dora warns against taking on more responsibility.

The travelers soon reach the coast near Marseille but find the port city dangerous and chaotic. When the Bentley breaks down in the hills, they are helped by a fisherman named Nico, who directs them to the quiet village of Saint-Benet.

There, they rent rooms at a modest guesthouse and begin to feel at home. Ellie wakes to the scent of sea air and senses that this peaceful harbor might be her new beginning.

As repairs on the Bentley delay their plans, the women explore the area, picnic on the beach, and find joy in simple pleasures. Dora’s sternness softens; Mavis gains confidence; Yvette begins to heal.

Ellie realizes that her impulsive escape has led her to the freedom she always sought. She rents a dilapidated villa, restoring it with the help of Louis, a witty local mechanic, and soon the place becomes their home.

A small conflict arises when Ellie discovers that her garden’s water supply has been diverted by a nearby viscount, Roland. Marching up to his grand château, she confronts him with unexpected confidence.

Roland, a charming yet spoiled aristocrat, is both amused and intrigued by her boldness. Their sparring turns into a cautious friendship.

Ellie learns that the villa once belonged to an opera singer, likely Roland’s father’s mistress, which deepens her curiosity about the estate’s past.

By Christmas, Ellie and her companions have settled into a rhythm of friendship and domesticity. They celebrate with neighbors, attend Mass, and exchange thoughtful gifts that symbolize their newfound closeness.

The following spring, Ellie’s son Colin visits unexpectedly, sent by Lionel to persuade her to return home as war looms. Their reunion is awkward but affectionate.

Colin is impressed by his mother’s transformation and reluctantly accepts her choice to stay in France. He also brings news that Mavis’s abusive husband has died, freeing her at last.

Life in Saint-Benet blossoms. Ellie befriends Nico, the fisherman who helped her, and a gentle bond grows between them.

When he takes her out to sea, she experiences joy and exhilaration, feeling truly alive. But their peace is soon interrupted when Yvette gives birth to a daughter, Jojo, and abandons her weeks later.

Ellie decides to raise the baby herself, supported by Mavis and Dora. The infant brings laughter and purpose to their household.

As war spreads across Europe, Saint-Benet falls under German occupation. Ellie’s life takes a dangerous turn when Nico and the local abbot recruit her to help smuggle Jewish refugees to safety.

Using her villa as a temporary shelter and Nico’s boat for transport, Ellie becomes part of the underground resistance. Her courage grows as she risks discovery night after night.

When Nico is injured, she nurses him, and their affection deepens into love.

Their covert operation thrives until betrayal strikes. Tommy, one of their English friends, is arrested by German soldiers after being denounced.

The soldiers raid Ellie’s villa, and though they find nothing, Tommy is taken away. Soon Ellie learns that Roland, desperate for German favor, was the informer.

He admits his betrayal and is cast out. Not long after, news reaches her that Nico and the abbot have been captured and executed, leaving her heartbroken.

She takes in Nico’s mother, mourning together as the village endures hunger and fear.

Months pass before liberation arrives. As the Allies advance, the villagers celebrate freedom, though Ellie can barely feel joy.

Then, miraculously, Nico returns—alive. He reveals that he and the abbot survived by pretending to be dead after their boat was destroyed.

His return brings Ellie renewed hope. They marry soon after, surrounded by friends and neighbors, their simple ceremony symbolizing survival and rebirth.

The war leaves deep scars, but life gradually resumes its rhythm. Ellie learns of the death of Tommy in Auschwitz and grieves deeply, while Clive, his companion, leaves to paint in his memory.

Years later, Lionel visits, seeking reconciliation, but finds Ellie transformed—happy, confident, and remarried. She gently but firmly refuses him.

A letter from Yvette, now living under her real name Jeanne-Marie, arrives. She writes that she has turned her life around and is raising her daughter safely, expressing gratitude for Ellie’s kindness.

Reading it, Ellie feels the journey has come full circle.

In her twilight years, sitting on the terrace of Villa Gloriosa with Mavis, Ellie reflects on the extraordinary path her life has taken. From a cast-off wife in England to a woman who found love, courage, and freedom in France, she realizes that her true adventure was not the journey itself but the discovery of who she could become.

Mrs Endicott’s Splendid Adventure thus closes as a story of rebirth, compassion, and enduring strength amid the turmoil of history.

Characters

Eleanor “Ellie” Endicott

Eleanor Endicott is the emotional and narrative core of Mrs Endicott’s Splendid Adventure. At the outset, she is portrayed as a quiet, dutiful Englishwoman whose life has been shaped by domestic routines and social expectations.

Her husband’s sudden demand for divorce jolts her from complacency, forcing her to confront a lifetime of submission and emotional neglect. Ellie’s journey—both literal and metaphorical—is one of awakening and reinvention.

Initially, her composure masks deep insecurity and loneliness, but through her travels and experiences, she transforms into a woman of conviction, capable of compassion, leadership, and love.

Her decision to leave England and drive to the Riviera symbolizes rebellion against societal norms. Ellie evolves from the repressed wife of a banker into a self-reliant figure whose empathy and courage drive the story’s humanitarian dimension, especially during wartime.

Her kindness to Yvette, her protection of refugees, and her resilience in grief demonstrate an inner strength that blossoms only once she frees herself from Lionel’s shadow. By the novel’s end, Ellie embodies the triumph of independence and emotional rebirth—a woman who redefines happiness on her own terms.

Lionel Endicott

Lionel serves as the catalyst for Ellie’s transformation. A prosperous but emotionally sterile banker, he represents the patriarchal rigidity of pre-war English society.

His calm cruelty in discarding his wife after decades of loyalty reveals his moral shallowness. Throughout the novel, Lionel remains largely unchanged—self-serving, rationalizing his betrayal as inevitable and civilized.

Even his later attempt at reconciliation, after Ellie has rebuilt her life, underscores his inability to grasp the depth of her growth. His role is that of a mirror—his coldness and entitlement highlight Ellie’s warmth, courage, and newfound independence.

Lionel’s downfall lies not in tragedy but in irrelevance; he becomes the remnant of a life Ellie has outgrown.

Mavis Moss

Mavis begins as a secondary figure—a working-class cleaning woman—but becomes one of the novel’s emotional anchors. Practical, outspoken, and fiercely loyal, she offers Ellie the first glimpse of genuine friendship and solidarity across class lines.

Her own suffering at the hands of an abusive husband contrasts with Ellie’s genteel oppression, illustrating how women of all backgrounds endured confinement and control. When Ellie helps Mavis escape her marriage, it cements their bond and reveals Ellie’s growing moral courage.

In France, Mavis evolves into a symbol of quiet endurance and domestic stability. Her transformation from servant to equal companion is profound; she rebuilds her confidence, learns new skills, and becomes a moral pillar during the Resistance.

By the end, her steadfast presence beside Ellie—older, wiser, and at peace—embodies survival and dignity.

Miss Theodora “Dora” Smith-Humphries

Miss Smith-Humphries, or Dora, is initially introduced as a rigid, intimidating churchwoman, yet her decision to accompany Ellie unveils a hidden longing for freedom. Facing terminal illness, she becomes both mentor and mirror to Ellie—a woman who has also lived within the confines of propriety but now seeks meaning before death.

Her blunt humor and courage bring balance to Ellie’s gentleness. Dora’s journey from moral austerity to joyful participation in life’s pleasures—splashing in the sea, celebrating friendship—adds poignancy to the novel’s theme of renewal.

Her acceptance of mortality and her generous gifts at Christmas mark her as a figure of grace, leaving behind both material and emotional legacies that sustain Ellie after her death. Dora’s arc reinforces the idea that liberation is possible even in one’s final days.

Yvette (Jeanne-Marie)

Yvette, later revealed as Jeanne-Marie, embodies youthful recklessness and desperation. When Ellie rescues her, she appears as a frightened runaway; yet her story unfolds in layers of deceit and vulnerability.

Her pregnancy, her lies about her background, and her eventual abandonment of her child portray her as a product of both hardship and fear. Though she betrays Ellie’s trust, she is never demonized—her flaws reflect the chaos and moral complexity of wartime Europe.

Yvette’s eventual redemption, revealed through her letter years later, underscores the enduring impact of Ellie’s compassion. Her arc is one of lost innocence and eventual self-forgiveness, linking the novel’s personal themes of maternal love and renewal with its broader moral vision.

Nico Barbou

Nico, the fisherman of Saint-Benet, is both love interest and moral counterpart to Ellie. Earthy, patient, and courageous, he embodies the resilience of ordinary people during war.

His connection to the sea mirrors Ellie’s connection to freedom—both are shaped by endurance and unpredictability. Nico’s kindness, his devotion to his mother, and his quiet heroism in the Resistance deepen the emotional stakes of the story.

His relationship with Ellie grows organically, built on mutual respect and shared values rather than passion alone. His apparent death and later return give the novel its emotional crescendo, turning tragedy into hope.

Their eventual marriage represents a union grounded in equality and shared experience—a stark contrast to Ellie’s first marriage. Nico stands as a symbol of integrity, love reborn from loss, and the courage to act selflessly in dark times.

Roland, Viscount de Saint-Clair

Roland, the young viscount, embodies the decay of old aristocracy. Idle, vain, and occasionally charming, he represents privilege detached from responsibility.

Ellie’s interactions with him reveal both her maturity and his weakness. While he offers glimpses of kindness, his ultimate betrayal—exposing the refugee network to the Germans—marks him as morally bankrupt.

Roland’s character arc is one of squandered potential; even his motives are steeped in cowardice and self-preservation. Through him, the novel critiques the superficiality of status without conscience.

His downfall contrasts starkly with the moral courage of the humble villagers, highlighting that nobility lies in deeds, not titles.

Father André and Abbot Gerard

The two clergymen in Mrs Endicott’s Splendid Adventure—Father André of Saint-Benet and Abbot Gerard of the island monastery—serve as moral beacons in a world unraveling under war. Father André represents community faith, offering kindness and connection to the villagers, while Abbot Gerard embodies spiritual compassion in action, risking his life to shelter Jewish refugees.

Their friendship with Ellie deepens her understanding of sacrifice and faith beyond doctrine. Abbot Gerard’s alliance with Nico transforms religion into resistance, a form of moral courage rather than passive prayer.

Together, they symbolize the enduring strength of goodness amidst human cruelty.

Clive and Tommy

Clive and Tommy, the English couple living near Ellie, bring warmth and humanity to her adopted life in France. Cheerful and practical, they help her adjust to village life and later become vital allies in the Resistance.

Tommy’s capture and death serve as one of the novel’s most tragic turns, revealing the devastating cost of moral bravery. Clive’s grief and eventual departure mark the quiet heartbreak that follows liberation—the recognition that freedom always comes at a price.

Their friendship with Ellie emphasizes the power of chosen family, forged through shared danger and compassion.

Madame Barbou

Nico’s elderly mother, Madame Barbou, adds emotional depth to the story’s closing chapters. Her stoic endurance during wartime and her later bond with Ellie after Nico’s presumed death highlight themes of maternal grief and resilience.

When she moves into the villa, she becomes part of the novel’s symbolic circle of women—each having lost and rebuilt, each sustaining the others through kindness. Her presence cements the idea that healing, though incomplete, is possible through shared strength.

Themes

Female Independence and Self-Discovery

In Mrs Endicott’s Splendid Adventure, the transformation of Eleanor “Ellie” Endicott from a submissive wife into a self-reliant woman forms the emotional and thematic core of the story. Her journey begins with personal devastation—the sudden collapse of a marriage that defined her identity for three decades—but evolves into an awakening of independence and purpose.

In England, Ellie’s life was dictated by domestic routines and social expectations. Her husband, Lionel, exemplified patriarchal complacency, viewing her not as an equal partner but as a fixture in his well-ordered world.

When he announces his affair and demands a divorce, Ellie’s rebellion against submission is not just a reaction to betrayal; it is a redefinition of self-worth. Her insistence on fair financial terms and her decision to embark on a journey to France mark her first true acts of autonomy.

In France, independence becomes tangible through experience rather than theory. Ellie takes charge of practical challenges—driving across a foreign country, managing repairs, handling finances, and protecting her companions.

Each obstacle strengthens her confidence, revealing the latent resilience that domestic life had suppressed. Her relationships with Dora, Mavis, and later Nico underscore her growing ability to lead without domination and to nurture without self-effacement.

By the novel’s conclusion, Ellie’s independence matures into emotional equilibrium: she no longer defines freedom as escape but as the ability to choose her path with courage and dignity. Her evolution reflects a broader commentary on women reclaiming identity in an era when divorce and self-sufficiency were social taboos.

Ellie’s independence, therefore, is not a solitary triumph but an emblem of modern womanhood emerging from tradition’s shadow.

Friendship, Solidarity, and Female Companionship

The novel’s enduring warmth arises from the solidarity among its women—a theme that transcends social class, age, and circumstance. Ellie’s companionship with Mavis and Dora begins as an unlikely alliance but becomes a source of strength and survival.

Mavis, a working-class woman trapped in an abusive marriage, and Dora, a terminally ill spinster yearning for one last adventure, represent different faces of confinement. Their companionship with Ellie evolves into a quiet sisterhood, where loyalty and emotional honesty replace societal hierarchies.

Their shared journey to the Riviera is both literal and symbolic—a crossing from dependence to mutual empowerment.

Throughout the story, Bowen uses moments of domestic intimacy to explore the transformative power of female friendship. Whether sharing laughter during a French harvest festival or working side by side in their adopted villa, the women create a household grounded in empathy rather than obligation.

Even in moments of conflict—Mavis’s fear, Dora’s stubborn propriety, Yvette’s deceit—their compassion prevails over judgment. The arrival of Yvette and her baby expands this theme into a generational continuum: the women not only support one another but also become protectors of new life and hope.

When war descends, their unity takes on moral significance. Together, they shelter fugitives and face danger with quiet heroism.

This solidarity, forged in shared struggle, becomes an act of defiance against the masculine violence of both domestic oppression and global conflict. By the end, friendship is portrayed not as dependency but as a moral force—one that gives meaning, resilience, and redemption to lives once confined by isolation.

War, Courage, and Moral Responsibility

As the narrative shifts into the wartime years, Mrs Endicott’s Splendid Adventure transforms from a story of personal emancipation into one of collective moral courage. The tranquil life Ellie builds in Saint-Benet is disrupted by the encroaching realities of Nazi occupation, testing the moral convictions of every character.

Ellie’s decision to shelter Jewish refugees at immense personal risk illustrates how ordinary people, driven by conscience rather than ideology, become heroes. Her villa—once a sanctuary of personal healing—becomes a haven for the persecuted, symbolizing the transformation of private freedom into public responsibility.

War also exposes character. Nico’s quiet bravery, Clive’s forged papers, and Tommy’s tragic fate reflect varying forms of sacrifice.

Ellie’s courage is not rooted in recklessness but in compassion. Her willingness to act, even after betrayal and loss, shows that moral strength often manifests through endurance rather than defiance.

The contrast between Ellie’s humanity and Roland’s cowardly treachery underlines Bowen’s moral vision: survival without integrity is meaningless, while sacrifice born of conscience restores dignity to suffering.

The war also deepens Ellie’s understanding of freedom. The independence she once sought for herself becomes inseparable from the freedom of others.

Her grief for Tommy and Nico’s presumed deaths forces her to confront the cost of moral choice, yet her endurance reflects a deeper, almost spiritual courage—the ability to continue loving and living after immense loss. Through the war, Bowen redefines heroism not through grand gestures but through steadfast compassion and moral clarity amidst chaos.

Love, Renewal, and the Possibility of Happiness

While the novel begins with the collapse of love, it ends with its quiet renewal. Ellie’s relationship with Nico represents a mature form of affection built on respect, shared values, and emotional equality.

Unlike Lionel’s cold pragmatism, Nico’s love is grounded in mutual understanding and kindness. Their bond emerges gradually—through shared meals, small acts of care, and mutual bravery—rather than through idealized romance.

Bowen presents this love as a reward not for beauty or youth but for emotional authenticity.

Love, however, extends beyond the romantic. The affection between Ellie and her companions, her care for baby Jojo, and her compassion for Nico’s mother all represent love as a sustaining moral energy.

In a world scarred by betrayal and war, this quiet, nurturing love restores faith in humanity. When Ellie and Nico marry after liberation, their union feels less like a romantic climax and more like a testament to endurance.

Their happiness is modest yet profound, rooted in shared survival and a mutual belief in goodness.

By the closing pages, Ellie’s life has come full circle: she is no longer the obedient wife of an English banker but a fulfilled woman who has rebuilt her world through courage, empathy, and the capacity to love again. Bowen’s portrayal of renewal suggests that even amidst devastation, the human spirit retains its power to rebuild—to find grace not by returning to what was lost but by embracing what has been hard-won.

Class, Identity, and the Redefinition of Social Roles

The novel also explores the shifting boundaries of class and identity in pre-war and wartime Europe. Ellie’s friendship with Mavis dismantles the rigid hierarchies that once defined her world.

Their partnership—an upper-middle-class Englishwoman and her working-class maid traveling as equals—represents a quiet social revolution. In Saint-Benet, their shared labor erases distinctions of privilege; all that matters is capability, kindness, and survival.

Bowen subtly critiques the artificiality of British class structures through Ellie’s growing identification with French village life. Freed from England’s social scrutiny, she discovers dignity in simplicity and community.

The contrast between her self-made home and the decaying grandeur of the viscount’s château reflects a deeper moral inversion: nobility is no longer inherited but earned through compassion and courage. Even Yvette’s story—a poor, deceived girl given a second chance—reinforces this theme by portraying redemption as accessible to all, regardless of birth.

By the novel’s conclusion, Ellie’s social transformation is complete. She moves from being the ornamental wife of privilege to an active moral agent embedded in a community defined by mutual respect rather than status.

The war accelerates this leveling of class distinctions, but Ellie’s acceptance of equality begins long before the conflict. Through her eyes, Bowen imagines a more humane society emerging from the ruins of old hierarchies—one where decency, courage, and kindness form the true measure of worth.