My Other Heart Summary, Characters and Themes

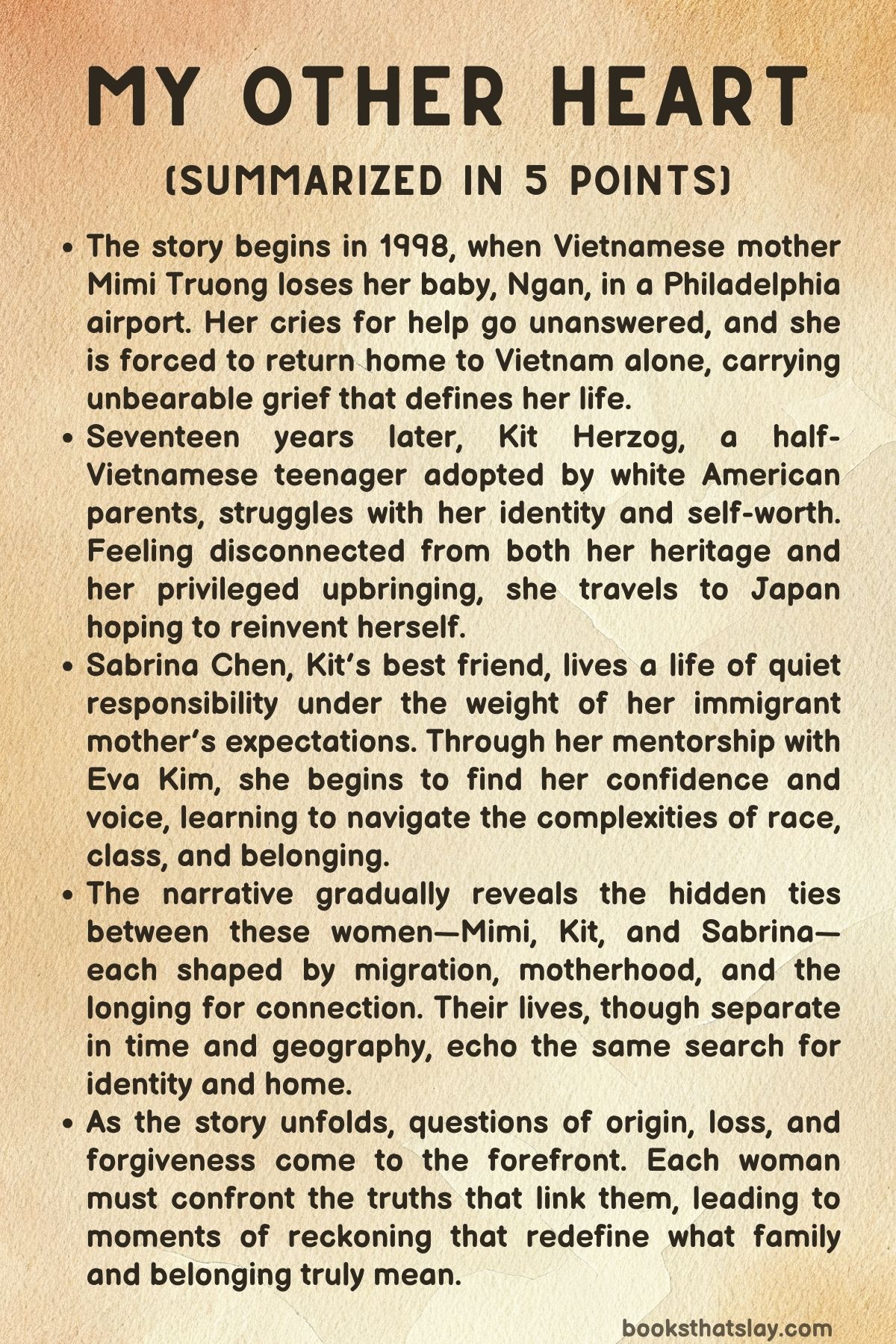

My Other Heart by Emma Nanami Strenner is a contemporary novel exploring the complex intersections of identity, migration, and motherhood. Set across Vietnam, America, and Japan, the story follows three women—Mimi Truong, a Vietnamese mother haunted by the loss of her child; Kit Herzog, a mixed-race American teenager grappling with her adoption; and Sabrina Chen, a Chinese American girl striving to define herself within cultural and class divides.

Through their interconnected lives, Strenner examines belonging, displacement, and the silent endurance of women shaped by borders, secrets, and love. The novel unfolds with quiet emotional precision, connecting generations through loss and rediscovery.

Summary

In May 1998, Mimi Truong, a Vietnamese woman traveling from Philadelphia to Saigon with her infant daughter, Ngan, faces a tragedy that alters her life. Exhausted and struggling with the alienation of America, she loses sight of Ngan at the Newark airport.

Amid chaos and misunderstanding, unable to communicate in English, she is sedated and deported back to Vietnam without her child. The disappearance destroys her spirit, leaving her in Saigon consumed by grief while her sister Cam tries and fails to console her.

Seventeen years later, her life continues under the weight of that single moment.

In 2015 Philadelphia, Kit Herzog, a high school student of mixed heritage adopted by white American parents, wrestles with questions of identity. She resents how people demand to know “where she’s really from,” and hides her discomfort behind sarcasm and rebellion.

Her relationship with her best friend, Sabrina Chen, reveals contrasts in privilege and temperament—Kit impulsive and assertive, Sabrina responsible and restrained. When Kit decides to spend the summer in Tokyo after a breakup, she frames it as a journey of self-discovery, but beneath her confidence lies uncertainty about who she truly is.

Raised in comfort, Kit invents fantasies about her origins, convinced her biological mother was Japanese, a fiction that shields her from the ambiguity of her past.

Sabrina’s life is more constrained. She and her mother, Lee Lee, live modestly in Philadelphia.

Lee Lee, a stern Chinese immigrant, demands obedience and discipline, leaving Sabrina feeling suffocated. She secretly dreams of attending Princeton and traveling to China, but financial hardship and family obligations weigh her down.

Her friendship with Kit, though genuine, exposes class differences—Kit’s carelessness toward Sabrina’s struggles deepens a growing rift between them. When a burst pipe forces Sabrina to spend her savings on repairs, her travel dreams vanish, and Kit’s overseas plans highlight the gulf between their worlds.

Assigned to intern at the Asian American Immigration Coalition, Sabrina meets Eva Kim, a confident lawyer who becomes her mentor. Eva challenges her to confront the stereotypes she endures and to use her voice rather than hide behind silence.

Sabrina begins to awaken to her own strength, learning to balance humility with ambition. Her experiences at the Coalition expose her to stories of immigration and injustice, helping her reframe her relationship with her own mother and community.

The narrative alternates between these parallel journeys. Mimi continues to live in Saigon, her life a quiet echo of loss.

She works tirelessly as a cleaner, still haunted by memories of Ngan. Kit, meanwhile, embarks on her summer in Tokyo, living with the Buchanan family—Amy, a reckless friend, and her brother, Ryo.

In Tokyo, Kit feels both liberated and alien. She observes Amy’s chaotic freedom and Yuriko Buchanan’s elegance, absorbing their contrasting ways of life.

Ryo’s steadiness and intellect draw her in, and their relationship becomes a brief but formative experience that teaches her about connection, honesty, and self-perception. Kit’s time abroad marks her transition from fantasy to reality, though she still avoids confronting her true origins.

Sabrina’s story deepens as she discovers she may be undocumented. Eva Kim pushes her to face this truth and helps her navigate her uncertain legal status.

Working alongside Eva, Sabrina witnesses the struggles of immigrants denied protection, such as a Thai woman named Achara who can’t access medical care. These encounters shift Sabrina’s understanding of her mother, making her see that Lee Lee’s rigidity stems from survival and fear rather than cruelty.

Their tense relationship gains new layers of compassion as Sabrina starts to grasp the weight of her mother’s sacrifices.

Meanwhile, Mimi returns to America after seventeen years, still searching for Ngan. In New Jersey, she works for a wealthy family and spends weekends scanning crowds in Philadelphia, hoping to glimpse her daughter.

Her persistence mirrors Lee Lee’s own resilience, both women bound by loss and motherhood.

Sabrina’s emotional world becomes more complicated when she grows close to Dave Harrison, a boy connected to both her and Kit. Their relationship blurs friendship and romance, stirring guilt and longing.

When Dave admits he values her friendship but doesn’t love her, Sabrina is heartbroken but begins to understand her own self-worth beyond romantic validation. Eva helps her see that heartbreak, too, can be a form of transformation.

Everything converges one summer afternoon at the Herzogs’ house. Kit hosts Ryo and his father, while Dave and Sabrina arrive together.

Suddenly, a thin Vietnamese woman appears—Mimi Truong—asking for “Katherine, adopted in 1998. ” The family freezes.

Through the doorway, Sabrina and Mimi meet eyes, realizing their resemblance. Panic overtakes Sabrina; she flees in Dave’s Jeep and accidentally hits Mimi, injuring her.

At the hospital, Eva arrives to mediate. Tests and stories confirm what intuition already knew: Sabrina is Mimi’s long-lost daughter, Ngan.

Eva arranges meetings between the women and explains the legal consequences. Lee Lee, who took the baby from the airport years earlier, faces potential imprisonment.

Mimi, compassionate and weary, refuses to press charges, wanting only to reconnect. Eva proposes that Lee Lee self-deport to avoid prison while pursuing DACA for Sabrina.

In detention, Lee Lee asks only that her daughter be safe. When Sabrina visits her before deportation, she demands to know why Lee Lee did it.

Lee Lee answers simply: “Because I had to. You needed me.

And I needed you. ” A flashback reveals the truth—Lee Lee, working at Newark Airport in 1998, found the unattended baby near Gate D12.

Lonely and invisible, she took the child and walked away, creating a life built on love and fear.

Months later, Sabrina lives with Eva and begins communicating with Mimi, who now resides in Ho Chi Minh City with her husband, Toan. Mimi, after years of despair, finds peace in reconnecting with her daughter.

By late 2015, Sabrina prepares to visit Vietnam, encouraged by Eva and supported by Dave, who remains a steady friend. She travels to Saigon, reflecting on everything she has lost and gained.

Standing in the city at dusk, she feels both anxious and free, ready to meet Mimi and begin a new chapter that unites her two lives.

My Other Heart closes with Sabrina sending a message to Dave: she has arrived. The long journey that began with a lost child and a mother’s grief ends with reunion and understanding.

Across continents and generations, the women’s stories—of loss, resilience, and identity—come full circle, revealing that love, even when fractured by distance and time, endures as the truest connection between them.

Characters

Mimi Truong

Mimi Truong stands at the heart of My Other Heart, embodying both the agony of loss and the resilience of motherhood. A Vietnamese woman scarred by displacement, her life unravels when her baby daughter vanishes at an American airport.

This trauma defines her existence — the bewildering bureaucracy, the cultural estrangement, and the coldness of the country that was supposed to offer safety. Mimi’s return to Vietnam is not a homecoming but an exile, marked by guilt and unending yearning.

She becomes a ghost of her former self, moving through life in a state of quiet mourning. Yet beneath her grief lies remarkable endurance.

When she later returns to America, years older and more fragile, she carries not bitterness but determination — a mother’s instinctual pull toward the child she lost. Through her, the novel explores how memory and identity fracture under migration, and how love, even in its most desperate form, can transcend borders and time.

Kit Herzog

Kit Herzog represents the contradictions of privilege and identity confusion. Adopted into a white American family, she lives in material comfort but emotional instability.

Her mixed Vietnamese heritage, coupled with an upbringing devoid of cultural anchors, leaves her desperate to belong somewhere — or to someone. Kit’s self-invented Japanese identity reveals both her imagination and her fragility; she constructs a myth about herself to avoid confronting the emptiness of not knowing her roots.

Her relationships — particularly with Dave Harrison and her best friend Sabrina — expose her insecurity. Kit’s charm often masks self-centeredness, yet she is never portrayed as malicious.

Her summer in Tokyo becomes both a literal and metaphorical search for meaning, as she seeks authenticity amid the facades she’s built. Through Kit, My Other Heart dissects the emotional cost of adoption, the subtle racism of assimilation, and the aching desire to rewrite one’s origins.

Sabrina Chen

Sabrina Chen’s journey in My Other Heart is one of awakening — from quiet obedience to self-awareness and strength. A first-generation Chinese American girl, she shoulders the burdens of her immigrant mother’s sacrifices and expectations while struggling to define herself beyond stereotypes.

Her friendship with Kit Herzog, both intimate and unequal, becomes a mirror for class and cultural tensions: where Kit is impulsive and entitled, Sabrina is cautious and dutiful. Sabrina’s relationship with her mother, Lee Lee, is fraught with love and repression; their bond oscillates between tenderness and suffocation.

The mentorship of Eva Kim ignites Sabrina’s transformation, teaching her to voice anger, claim identity, and confront injustice. The revelation that she was the lost child Mimi once mourned shatters and redefines her sense of self.

Sabrina’s path — from silence to speech, from shame to empowerment — encapsulates the novel’s central concern: how the children of migration inherit both the pain and resilience of those who came before them.

Lee Lee

Lee Lee embodies the survival instincts of the immigrant mother, her entire being shaped by hardship and secrecy. Once a young Chinese woman smuggled into America, she endures exploitation, widowhood, and undocumented existence with stoic determination.

Her act of taking baby Ngan — later known as Sabrina — from the airport, while morally fraught, emerges as an act of salvation in her eyes. She raises Sabrina under a veil of fear and discipline, teaching restraint as a means of protection.

To outsiders, she is severe and proud; to her daughter, she is both a protector and a prison. Yet Lee Lee’s love, though flawed, is profound — a love born of trauma and necessity rather than sentiment.

When she finally chooses deportation over imprisonment, she sacrifices herself again for Sabrina’s future. Lee Lee’s story reveals the quiet heroism and tragedy of those whose motherhood must coexist with illegality and erasure.

Eva Kim

Eva Kim is the novel’s moral catalyst — a woman of intellect, compassion, and fiery pragmatism. As an immigration lawyer and mentor, she represents what Sabrina and others might become: someone who channels personal struggle into collective empowerment.

Eva’s sharpness and humor balance her empathy; she cuts through pretense and compels others to confront uncomfortable truths. Her mentorship transforms Sabrina’s view of herself and her world, teaching her to harness her story rather than hide it.

Eva’s own life, briefly glimpsed, suggests a balance between vulnerability and control — she has faced her share of loss and compromise, yet refuses to let pain define her. Through Eva, My Other Heart honors the women who turn survival into advocacy, and who redefine success not through assimilation but through courage and truth.

Dave Harrison

Dave Harrison functions as a mirror through which the young women measure themselves and their desires. He is kind yet oblivious, embodying the comfortable indifference of privilege.

For Kit, he is a romantic conquest that validates her identity; for Sabrina, he is a rare listener who seems to see her worth. Dave’s relationships with both reveal the social and emotional hierarchies embedded in race, class, and gender.

His inability to grasp the depth of the girls’ emotional struggles underscores how insulated his world is from theirs. Yet he is not without empathy — his support during Sabrina’s darkest moments reflects genuine care.

Ultimately, Dave symbolizes the limits of cross-cultural understanding when privilege remains unexamined; he is both a comfort and a boundary that Sabrina must transcend to grow into herself.

Toan

Toan, Mimi’s husband in Vietnam, serves as a figure of steadiness amid emotional upheaval. Though secondary to the central female narratives, his presence grounds Mimi’s later life.

His patience and quiet love contrast her obsessive longing for her lost daughter. Yet even he cannot fully bridge the distance between them — a gap created by trauma and years of separation.

Toan’s later involvement in reuniting Sabrina and Mimi, done in secret, reflects both compassion and respect for Mimi’s need for closure. He represents the ordinary goodness of those who bear witness to suffering without trying to erase it.

Through Toan, the novel suggests that healing often begins not with grand gestures but with the simple, steadfast presence of those who choose to stay.

Themes

Displacement and Belonging

The sense of displacement in My Other Heart forms an emotional undercurrent that binds the characters across generations and geographies. Mimi Truong’s traumatic loss of her daughter at an American airport encapsulates the alienation of immigrants who are caught between nations that neither fully claim nor understand them.

Her return to Vietnam does not restore peace; instead, it underscores how home becomes a place remembered rather than inhabited. For Kit Herzog, displacement takes a subtler but equally corrosive form — that of a transracial adoptee growing up amid affluence but feeling fundamentally unmoored.

She lives in a house that provides comfort yet denies connection, raised in a culture that consumes her heritage as novelty while erasing its complexity. Sabrina Chen’s story extends this theme into a second generation of immigrants who are born or raised in the host country yet remain treated as outsiders.

Her frustration with being seen as the “smart Asian girl” reflects the exhaustion of being categorized before being known. Across all three women, belonging is a shifting mirage: cultural, emotional, and familial homes remain elusive.

Emma Nanami Strenner uses these characters not to romanticize the search for identity but to show how displacement corrodes the ability to feel whole. The act of belonging is portrayed not as arrival but as endurance — the daily negotiation of language, memory, and love across invisible borders that no paperwork or passport can erase.

Motherhood and Loss

Motherhood in My Other Heart is both a redemptive force and a site of devastation. Mimi’s story begins with the most primal loss imaginable — the disappearance of her infant — and the rest of her life becomes a ritual of grief.

Her maternal love persists in absence, surviving without the child it was meant to nurture. Lee Lee, Sabrina’s adoptive mother, transforms motherhood into a form of resistance.

Having lived undocumented, she channels her fear and deprivation into fierce control, believing that strictness is protection. Her act of taking the lost child, while morally fraught, is born from an instinct to love in a world that gave her none.

Sally Herzog, Kit’s adoptive mother, embodies yet another face of loss: infertility and the silent panic of a mother who fears being replaced by a biological past she cannot access. Through these intertwined portraits, the novel redefines motherhood as an act beyond biology — a continuum of sacrifice, guilt, and devotion that transcends legality or bloodline.

Strenner’s portrayal rejects sentimentality; love does not rescue these women but binds them to their pain. Even when reconciliation occurs, it carries the residue of trauma.

The reunion between Mimi and Sabrina is tender but uneasy, a reminder that maternal bonds can heal and wound in the same gesture. The novel insists that motherhood, for these women, is not defined by who gives birth but by who endures for love’s sake.

Identity and the Construction of Self

The characters in My Other Heart continuously construct and reconstruct their identities in response to the social worlds that confine them. Kit invents a Japanese heritage for herself, an act of self-deception that arises not from vanity but from a desperate need for coherence.

Her lie is a defense against the void of not knowing who she is or where she belongs. Sabrina’s journey, by contrast, exposes how identity can be both imposed and resisted.

She is assigned a role — diligent, compliant, predictable — and must fight to reclaim her individuality from the stereotypes that define her. Mimi’s identity fractures under colonial and postwar histories that render her voiceless: first as a refugee, then as a laborer in a foreign land.

Strenner shows how these identities are less stable categories and more survival mechanisms. Each woman wears a version of herself to navigate an environment structured by race, class, and power.

Yet, their identities also evolve through encounter — Kit’s immersion in Tokyo, Sabrina’s mentorship under Eva Kim, Mimi’s reunion with her daughter. Identity in this world is not discovered but built, layer by layer, through the friction of misunderstanding, shame, and longing.

By the novel’s end, these women do not arrive at certainty but reach a fragile awareness: the self is not an inheritance but a creation, a story told and retold until it feels true enough to live in.

Race, Privilege, and Social Hierarchies

Strenner uses the contrast between Kit and Sabrina to expose the quiet hierarchies embedded within multicultural societies. Though both are of Asian descent, Kit’s proximity to whiteness — through her upbringing in a wealthy adoptive family — grants her freedoms that Sabrina cannot imagine.

Her rebellion, from impulsive travel to self-invention, is cushioned by privilege. Sabrina’s life, shaped by her mother’s undocumented status, is a daily exercise in invisibility.

She works to exist within systems that were not built for her, enduring the casual condescension of teachers and peers who see her as a model minority rather than a person. Through their friendship, Strenner reveals how race operates not just as color but as context — mediated by class, language, and citizenship.

Lee Lee’s encounters with the American upper class further amplify this theme: her dignity is mistaken for aggression, her knowledge for rudeness. The novel does not offer easy binaries of oppressor and oppressed; instead, it exposes how power circulates subtly, shaping even intimate relationships.

Dave Harrison’s interactions with both girls illustrate how privilege masquerades as kindness, how empathy can coexist with blindness. By tracing these tensions across homes, classrooms, and workplaces, Strenner dissects the architecture of privilege — showing how it isolates as much as it protects, and how its quiet inheritance shapes lives for generations.

Migration and the Search for Home

Migration in My Other Heart is portrayed as a force that dislocates not only bodies but generations. Mimi’s flight from America to Vietnam and back again mirrors the oscillation between survival and belonging that defines the immigrant condition.

Lee Lee’s own migration — illegal, dangerous, and lonely — transforms her into someone who values security over freedom. Her secrecy and fear shape Sabrina’s upbringing, leaving the daughter to inherit not only her mother’s dreams but her anxiety.

For Kit, travel becomes an aesthetic adventure, a way to rebrand herself rather than escape. Yet, her time in Tokyo confronts her with the uncomfortable truth that movement alone cannot substitute for identity.

Through these arcs, Strenner reframes migration as an emotional journey rather than a geographical one. The characters move endlessly — from Saigon to Philadelphia, from Tokyo to New Jersey — yet home remains intangible.

The return to Vietnam, the deportation of Lee Lee, and Sabrina’s eventual flight to Saigon close the circle, but not neatly. Each woman’s path shows that migration never truly ends; it becomes an inheritance, shaping how descendants dream, fear, and love.

Strenner captures the ache of living between worlds, where nostalgia becomes both a refuge and a wound, and where home is finally understood as not a place but a connection reclaimed.