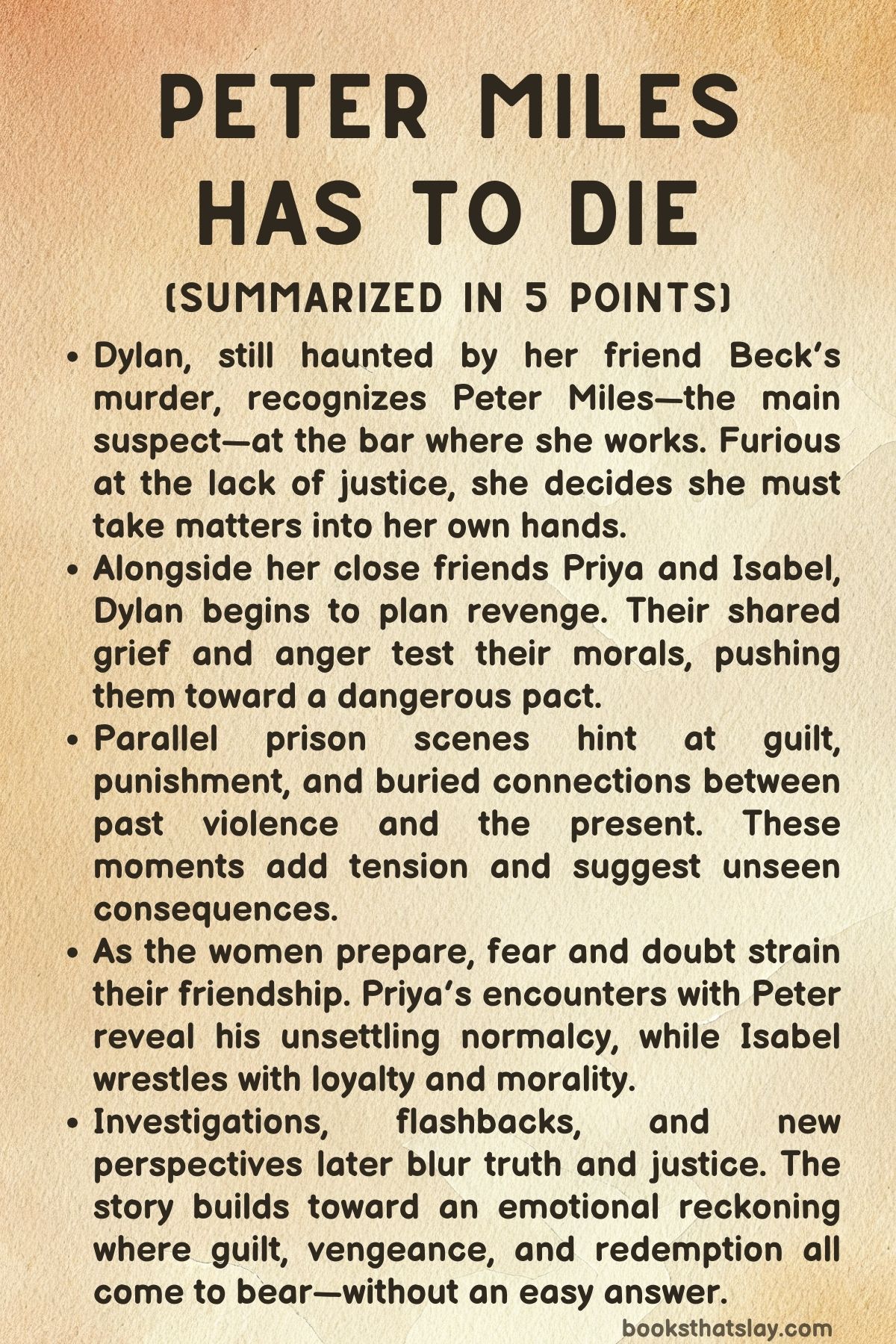

Peter Miles Has to Die Summary, Characters and Themes

Peter Miles Has to Die by Katie Collom is a psychological crime novel about grief, justice, and the blurred lines between vengeance and morality. The story centers on three women—Dylan, Priya, and Isabel—whose lives collapse after the brutal murder of their friend Beck.

When Dylan encounters Peter Miles, the man they once suspected, she decides that waiting for justice is no longer an option. What begins as shared grief turns into a conspiracy to kill. Through intercut prison reflections, shifting loyalties, and emotional unraveling, Collom examines how pain and guilt can transform ordinary people into avengers of their own making.

Summary

The story opens with Dylan, a bartender at Aces of Spades, haunted by the murder of her best friend, Beck. One night, she is stunned when Peter Miles—the man suspected in Beck’s disappearance—sits at her bar as if nothing happened.

Rage floods her, and she decides that the system has failed Beck. Dylan resolves to take justice into her own hands: Peter Miles must die.

While Dylan begins planning, the narrative alternates between her story and the reflections of an unnamed inmate in a Texas prison. These interludes hint at guilt, insomnia, and memories of a woman—foreshadowing the eventual consequences of revenge.

Dylan’s closest friends, Priya, a nurse, and Isabel, a teacher, are still grappling with Beck’s death. When Dylan reveals that Peter has returned to town and that she’s been serving him at the bar, her friends are horrified.

Isabel pleads for caution, while Priya insists that murder cannot be justified. Dylan, certain that the justice system is indifferent, challenges them: will they help her or turn her in?

Despite hesitation, loyalty and shared trauma tie them together.

Through flashbacks, readers see Beck in happier times, gushing about dating a police officer named Peter Miles. Dylan’s suspicion of him began then, and her hatred only grows as she encounters him again at the bar.

She spits in his drink to assert a small, defiant control, but her fury needs an outlet. Soon she begins planning his death, setting strict rules—no written notes, no digital traces—and dividing responsibilities among her friends.

Priya’s task is reconnaissance. She drives to Peter’s house, expecting a rundown place, but instead finds a well-kept suburban home, suggesting he hides behind normalcy.

She notices an older woman who may be his mother and records details of his routine. Her confidence wavers when Peter himself approaches her car, polite but armed, confirming he is as dangerous as ever.

She retreats, shaken by how close she came to exposure.

Meanwhile, grief consumes Beck’s parents. Isabel visits them and finds their home hollowed by loss.

Mr. Grant admits to wanting revenge, while Mrs.

Grant lashes out in denial and rage. Later, Isabel tells Dylan and Priya that the police have arrested a woman named Melanie, another suspect from Beck’s psychiatry program.

Dylan dismisses the theory, convinced it’s a diversion to protect Peter. The argument reignites the trio’s tension until Isabel, desperate to act, volunteers to help bait Peter.

A flashback to Beck’s New Year’s Eve party shows Dylan meeting Peter for the first time and warning Beck that he’s bad news. Beck laughs it off.

In the present, Dylan continues monitoring Peter’s bar habits. She meets Bree, a regular at Aces, who becomes both a friend and, eventually, a romantic distraction.

Bree gives Dylan a book of poetry and her number, hinting at a future Dylan knows she doesn’t deserve.

The women locate an abandoned waterfront house as the site of their plan. Inside, they gather tools—rope, a gag, wire, and a knife.

The discussion turns grim, but their shared determination steels them. They swear to finish the job even if one falters.

Flashbacks to Beck’s final days show her withdrawing and terrified of Peter’s harassment, refusing help from Priya out of shame or fear.

On the night of the planned murder, Peter returns to Aces. Dylan serves him calmly, adding crushed pills to his drink while masking her nerves.

He boasts that he’s getting his job back with the police, a reminder of how little justice means. Dylan excuses herself outside, where she runs into Bree and arranges another date—an echo of the life she might have had.

She returns to finish what she started.

Later chapters shift to Detective Bree, now investigating Peter Miles’s death. Her partner, Mike, helps reconstruct the timeline: the three friends had motive and alibis, but the case feels off.

Bree visits Priya, who nervously admits to having followed Peter once but denies any involvement in the murder. Bree’s intuition tells her the truth lies among the three women, yet she also senses something deeper.

Flashbacks reveal that Bree, too, has a personal history with Peter—he assaulted her in college, and she has carried the trauma ever since. At Beck’s funeral, she realizes with clarity why someone like Peter had to die.

As the investigation tightens, the friends come under pressure. Isabel is harassed by unknown callers and pulled over by men pretending to be cops.

Priya’s car is vandalized, and Dylan is attacked outside the bar. They suspect police retaliation for Peter’s death.

Fear and paranoia fracture their unity. Dylan urges them to stay silent and “act normal,” but the guilt and stress begin to consume Isabel.

The narrative returns to Bree, who faces pressure from her department to close the case. Evidence against the women is thin, yet the chief demands a scapegoat.

Bree’s internal conflict deepens—she knows the truth but feels complicit. Meanwhile, a sequence of prison vignettes, set years earlier, continues to mirror the themes of guilt, punishment, and endurance.

Eventually, the harassment stops when two corrupt officers are arrested. Dylan invites her friends over, hoping to restore some calm.

Isabel, overcome by guilt, proposes confessing to Peter’s murder alone to spare the others. Priya refuses, terrified of prison.

Dylan argues that Peter’s death cost the world nothing compared to what he took from them. She asks Isabel to hold off while she “figures something out.

The final act reveals the choice that defines the ending. Bree decides to take the blame.

She confesses to killing Peter Miles, telling her partner that she had motive—he assaulted her years ago—and that she manipulated the investigation to protect others. Her confession, though partially untrue, brings closure to the department and shields the three women from prosecution.

In the aftermath, time passes. Dylan now owns a bar called That Good Night Pub.

One day, she receives a letter from Texas State Penitentiary—Bree’s final message. Bree tells her to stop writing, explaining she confessed not out of guilt but because she wanted to protect the others and end the cycle of ruin that Peter started.

She has accepted the sentence as her own form of peace.

Dylan reads the letter with Priya, who visits with her dog, Echo. They toast to Beck’s memory and to Bree’s sacrifice.

Isabel, now living in Mérida, sends postcards that speak of recovery and distance. The women acknowledge Bree as their “scapegoat,” the one who bore their collective sin.

As they raise their glasses—“To Bree”—the story closes not with triumph but with quiet recognition of how vengeance, once unleashed, never leaves anyone unscarred.

Characters

Dylan Darcy

Dylan stands as the emotional core and moral paradox of Peter Miles Has to Die. Haunted by her best friend Beck’s brutal murder, Dylan’s grief curdles into a consuming need for vengeance that defines every decision she makes.

Working as a bartender at Aces of Spades, she becomes both hunter and haunted—spying on Peter Miles with cold precision while masking her inner storm beneath a façade of control. Dylan’s actions are driven by a deep mistrust of institutional justice, convinced that the police’s apathy leaves her no choice but to act.

Her friendship with Priya and Isabel deteriorates as her obsession isolates her, revealing the corrosive nature of vengeance. Despite flashes of tenderness, especially with Bree, Dylan’s emotional life is a battlefield of guilt, rage, and loyalty.

The novel paints her as both avenger and victim, consumed by the very violence she seeks to correct. Ultimately, Dylan’s determination transforms her from a grieving friend into an architect of moral collapse, highlighting the dangerous intimacy between justice and retribution.

Priya Shah

Priya’s moral and psychological turmoil forms the novel’s quiet backbone. A nurse by profession, she represents compassion and empathy, yet finds herself drawn into Dylan’s vengeful plot despite her deep moral reservations.

Her world is a balance of care and chaos—tending to battered women at work while battling guilt and fear in private. Priya’s participation in the plan is reluctant, guided more by loyalty to Dylan and grief for Beck than by belief in revenge.

Her rationality makes her the moral compass of the group, constantly questioning the ethics of their actions. Yet, as the story unfolds, her fear of exposure and punishment corrodes that moral clarity.

The threats, vandalism, and harassment she suffers afterward intensify her descent into paranoia. Through Priya, the author explores how ordinary people can be swept into extraordinary violence, showing that even good intentions can become complicit in tragedy when justice feels unreachable.

Isabel Guerrero

Isabel’s journey is one of unraveling sanity and guilt. A friend pulled into Dylan’s plan through emotional manipulation and shared grief, she oscillates between moral outrage and fearful compliance.

Unlike Priya, Isabel’s fragility stems from emotional rather than ethical uncertainty. Her attempts to lead a normal life—managing a relationship, maintaining appearances—crumble as trauma and paranoia tighten their grip.

Isabel’s post-crime deterioration is one of the novel’s most tragic arcs: she becomes disoriented, haunted by guilt, and desperate for redemption. Her impulse to confess underscores her need for moral purification, even at the cost of her own freedom.

Isabel’s psychological decay exposes the unbearable weight of complicity, turning her from bystander to victim of her own conscience. She becomes a symbol of what vengeance destroys—not just its target, but everyone tethered to it.

Bree

Bree embodies both justice and sacrifice, a woman who straddles the line between law and vengeance. Initially appearing as a detective investigating Peter Miles’s murder, her backstory reveals a history of trauma—she too was assaulted by Peter in college.

This revelation transforms her from neutral investigator to a figure of profound emotional conflict. Her growing relationship with Dylan complicates her sense of duty; affection, empathy, and shared pain bind them in ways neither anticipates.

When Bree ultimately confesses to Peter’s murder, she becomes the novel’s moral scapegoat, shouldering guilt to free others. Bree’s imprisonment represents both an act of defiance and redemption—she chooses to bear the consequences of violence, reclaiming agency from a system that failed her and Beck alike.

Through Bree, the novel explores the redemptive, self-destructive nature of confession and the tragic beauty of chosen culpability.

Peter Miles

Peter Miles is less a man than a shadow—his presence, though limited, drives the novel’s entire emotional landscape. Charismatic, manipulative, and violent, Peter represents the embodiment of unchecked male power.

His relationship with Beck and his subsequent behavior reveal a man who wields charm as a weapon, using authority to mask predation. Even after his death, Peter’s specter persists in every scene—his ghost lingers not as remorse but as the enduring consequence of abuse.

For Dylan, Priya, Isabel, and Bree, Peter symbolizes everything the world refuses to punish. His character serves as the gravitational center of moral decay, drawing every woman in the story toward vengeance, guilt, or ruin.

The brilliance of his portrayal lies in absence—he is most powerful when unseen, when his influence manifests through the destruction he leaves behind.

Rebecca (Beck) Grant

Beck’s death is the emotional and narrative catalyst of the entire novel. Though she exists primarily in memory and flashback, her vibrancy and vulnerability shape the motivations of all who loved her.

Beck’s relationship with Peter exposes her naïveté and yearning for validation, which tragically blind her to danger. Through the grief of her friends, Beck becomes both martyr and myth, a lost innocence that propels vengeance and sorrow alike.

Her murder fractures her circle of friends, binding them together in guilt and desperation. Beck’s memory operates as both a wound and a compass—the reason for Dylan’s descent, Priya’s paralysis, Isabel’s collapse, and Bree’s ultimate sacrifice.

In the end, Beck’s presence underscores the haunting truth of the story: that love and loss, when corrupted by violence, can turn justice into its own form of damnation.

Themes

Grief and Its Transformation into Vengeance

In Peter Miles Has to Die, grief is not merely an emotional response—it becomes a driving force that distorts morality and propels the characters into irreversible choices. Dylan’s grief over Beck’s murder is visceral and consuming; it manifests not as sorrow but as obsession.

She channels her pain into a mission, believing that vengeance is the only language justice will understand. Her mourning mutates into a fixation that isolates her from rational thought, friendships, and even self-preservation.

The way she tends bar, spits in Peter’s drink, and constructs elaborate plans for revenge exposes how grief corrodes her sense of self and ethics. Priya and Isabel, though initially hesitant, are drawn into Dylan’s spiral, each confronting how their unresolved pain seeks expression.

The book portrays grief as a contagion—it infects every relationship, bending empathy into complicity. Through interwoven perspectives, Katie Collom illustrates that grief, left unattended, becomes a weapon: it convinces ordinary people that killing can be a form of healing.

Even the prison sequences, where remorse is distilled through years of confinement, underscore how grief lingers long after the act of vengeance. By the end, grief is circular; it births revenge, which then creates more loss.

Dylan’s eventual calm, mirrored by Bree’s sacrifice, reflects the illusion that vengeance can soothe pain. The narrative insists that true closure never comes from retaliation—it merely shifts the weight of suffering from one set of shoulders to another.

Justice and the Corruption of Moral Certainty

The novel interrogates the meaning of justice in a system that continually fails women. Dylan’s conviction that “Peter Miles must die” arises from her disillusionment with institutional justice—the police’s indifference, the manipulation of power by men like Peter, and the helplessness of victims who are repeatedly dismissed.

Her version of justice becomes personal and punitive, rooted not in law but in emotional truth. Yet as she plots the murder, her justification begins to erode.

The reader watches the line between justice and revenge blur until it becomes unrecognizable. Priya’s profession as a nurse places her in direct conflict with this ideology—her vocation centers on saving lives, yet she is persuaded to consider taking one.

Isabel’s moral confusion further complicates the picture; her desire to protect her friends collides with her understanding of right and wrong. Collom portrays justice as something inherently unstable when filtered through trauma.

The authorities—embodied by corrupt cops, an indifferent chief, and a manipulative system—mirror the moral decay the women fear. Bree’s eventual confession reframes justice entirely: she assumes guilt not because she is culpable but because someone must pay.

In doing so, she exposes how justice often demands a sacrifice rather than truth. The book’s closing scenes, with Dylan running a new bar and reading Bree’s letter, suggest that justice in this world is transactional—achieved not through righteousness but through survival and silence.

Female Solidarity and the Fragility of Loyalty

The friendship among Dylan, Priya, and Isabel stands at the emotional center of Peter Miles Has to Die, revealing both the strength and volatility of female bonds under pressure. Their unity originates from shared grief and outrage, but as the plan unfolds, their loyalty becomes a moral battlefield.

Dylan’s dominance in the group stems from her ability to transform despair into action; Priya’s cautious pragmatism and Isabel’s emotional instability form the counterweights. The trio’s shifting dynamics expose how solidarity can be both empowering and destructive.

Their collective conspiracy binds them together in secrecy, yet the very act of uniting against Peter begins to fracture them. Trust, once a source of comfort, becomes suffocating, as each woman fears betrayal more than punishment.

Collom’s portrayal of their bond resists sentimentality—it is messy, coercive, and charged with guilt. The novel suggests that sisterhood under trauma often blurs moral boundaries: love becomes protection at all costs.

When Bree enters their orbit, her connection to Dylan introduces a new kind of solidarity, one based on shared pain rather than friendship. Bree’s final act of taking the fall becomes the ultimate expression of female loyalty—self-destruction as salvation for others.

Through these women, Collom portrays solidarity as both a refuge and a curse, capable of nurturing resilience and perpetuating violence in equal measure.

Memory, Guilt, and the Weight of the Past

Throughout the narrative, memory operates as both torment and evidence. Dylan’s recollections of Beck, fragmented and replayed in obsessive loops, keep the dead alive but also trap the living in a state of paralysis.

Each woman is haunted by a different memory—Priya by the moment she followed Peter to his home, Isabel by the echo of the night that changed everything, and Bree by her college assault. These memories do not fade; they dictate action, shaping guilt into a living presence.

Collom crafts guilt not as remorse but as endurance—a relentless reminder that every decision, no matter how justified, leaves an indelible mark. The prison vignettes mirror this idea through anonymous narrators who measure time in guilt rather than years.

The act of remembering becomes a form of punishment; it denies peace even when justice is served. The letter Dylan receives at the end, in which Bree asks her to stop writing, is a symbolic severance from the cycle of recollection.

Bree’s choice to bear the guilt for Peter’s death encapsulates how memory transforms into moral burden—someone must carry it so others can forget. Yet, as the women toast Bree, their attempt at closure feels incomplete.

The past, though buried, continues to dictate their present. In this way, the novel argues that guilt is never truly expiated; it merely changes hands, passed along like an inheritance no one can refuse.