The Battle of the Bookshops Summary, Characters and Themes

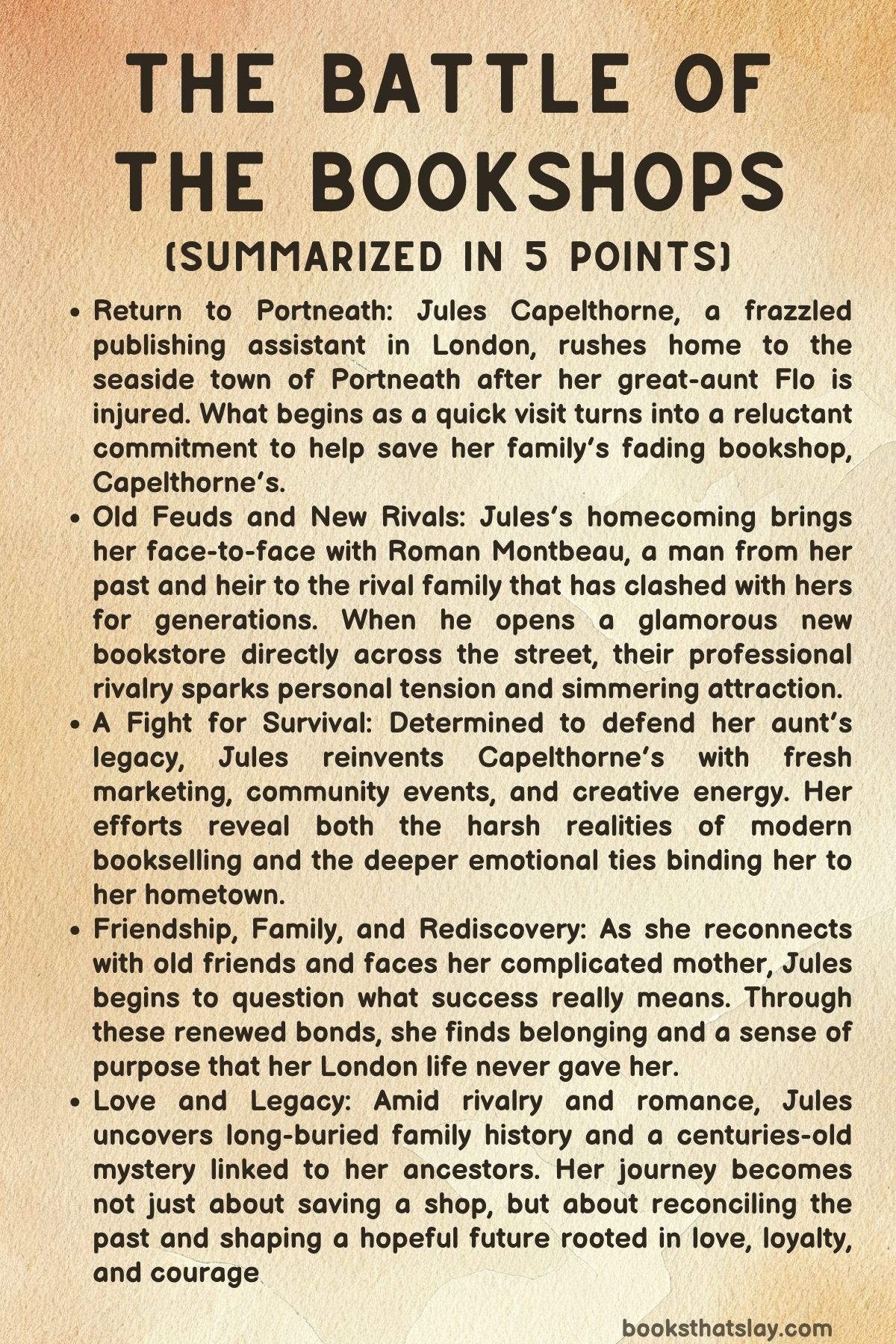

The Battle of the Bookshops by Poppy Alexander is a charming contemporary novel set in the coastal town of Portneath, where rivalry, family legacy, and love collide between two bookstores—and the families that own them. It follows Jules Capelthorne, a weary London publishing assistant who returns home to help her injured great-aunt Flo revive their century-old bookshop.

Across the street stands Roman Montbeau, her old adversary and heir to the rival family empire, who has opened a sleek new store designed to crush hers. As competition escalates, past grudges resurface, and unexpected affection threatens to rewrite the feud’s final chapter.

Summary

Jules Capelthorne leaves behind her demanding London job to return to her hometown, Portneath, after receiving an urgent call from her mother. Her great-aunt Flo has suffered a fall, leaving her unable to manage Capelthorne’s Books, the family shop that has stood for generations.

Arriving in Devon, Jules discovers that Flo is alive but frail, and that the beloved bookshop—once the heart of the town—is now in danger of closing. Despite intending to stay only for the weekend, guilt and affection compel her to help reopen it.

At the station, Jules encounters Roman Montbeau, a confident man from her youth and member of the rival family long at odds with the Capelthornes. Their frosty reunion foreshadows the rekindling of the ancient feud that has divided their families for centuries.

When Jules learns that Roman is behind a new business venture in Portneath, unease grows—but nothing prepares her for the shock of seeing his new, glamorous shop unveiled directly across the street. The Portneath Bookshop gleams with modernity, instantly threatening the faded Capelthorne’s.

Determined not to let Flo’s legacy disappear, Jules decides to stay in Portneath longer, even at the cost of her job in London. She cleans and restores the old shop, reconnecting with childhood memories and rediscovering the comfort of her roots.

Her efforts are rewarded with the slow return of customers, aided by Flo’s unwavering spirit and the loyalty of a few locals. Yet Roman’s store prospers, its glossy design and café drawing crowds away from Capelthorne’s.

Jules’s anger only deepens when her old friend Freya’s patisserie begins supplying Roman’s café, blurring friendship and betrayal.

As competition intensifies, Roman remains both rival and enigma. Beneath his charm lies a man torn between ambition and conscience.

His new store, though successful, weighs on him as he sees the toll it takes on Jules. Their encounters are full of tension—flashes of hostility mixed with an undeniable attraction that neither can ignore.

They cross paths at the local café, town events, and even at Freya’s engagement celebration, where sharp words give way to reluctant camaraderie. Yet each knows that their budding feelings threaten to shatter family loyalties.

At Capelthorne’s, Jules modernizes operations, introduces social media promotions, and restores the neglected upstairs rooms. With help from Charlie, a spirited PhD student who volunteers to catalog the antiquarian stock, she discovers forgotten treasures—including an old medical notebook later dubbed the Capelthorne grimoire.

As Flo heals, her romantic friendship with a gentle widower named Graham brings moments of warmth to the household. Meanwhile, Jules’s small victories—story hours, themed displays, author signings—revive the community’s affection for the store.

Despite these efforts, Roman’s success looms. His promotions, discounts, and charm draw many of Flo’s old customers.

When Jules learns that Roman’s family owns the lease on Capelthorne’s property, she begins to suspect that the feud is destined to repeat itself. Yet, against her better judgment, attraction overcomes resentment.

Shared encounters turn to stolen moments and late-night conversations, leading to an unexpected romance between the descendants of two enemy families.

Their relationship flourishes in secret, but tensions rise when Jules discovers the Montbeaus’ true leverage. Flo confesses that their shop’s lease—granted a century ago—will soon expire, reverting ownership to the Montbeaus.

Roman pleads with his powerful father to spare the Capelthornes, but business interests prevail. Unable to tell Jules, he grows increasingly distressed.

When the truth surfaces, Jules feels betrayed, believing Roman complicit in the plan to reclaim her family’s shop. Their relationship collapses under the weight of love and legacy.

While Jules and Flo despair, Charlie continues researching the ancient grimoire. His findings, supported by historian Professor Brynlee Roberts, reveal that Bridget Capelthorne, their ancestor, was executed for witchcraft in 1685—one of England’s last such victims.

Her writings show the same courage and intelligence Jules sees in herself, transforming the book into both a personal and historical revelation. The discovery reignites Jules’s resolve: even if the shop must close, the Capelthorne legacy will endure through history.

Meanwhile, tragedy strikes when a fire damages Roman’s store, ending his commercial venture. Freed from the burden of rivalry, he realizes that his ambitions mean little without Jules.

At the same time, Flo’s health falters, prompting Jules to rethink her priorities. Together, they decide to attend the London rare book fair to value the grimoire, where it draws tremendous attention from Sotheby’s specialists.

When the manuscript is auctioned, it sells for an astonishing £535,000, its historical significance captivating collectors worldwide.

The sale transforms their fortunes. Flo uses part of the proceeds to buy a charming cottage in Middlemass, securing her retirement.

Jules pays off debts, ensures the shop’s continuity, and looks toward a peaceful future. Roman, now estranged from his father but free from guilt, reconciles with Jules.

Their love, tested by rivalry and secrets, finds new strength in forgiveness. They attend family gatherings, blending humor with uneasy truce, as the once-hostile clans begin to heal old wounds.

In the novel’s final chapters, reconciliation replaces enmity. Jules and Roman marry quietly, joining their surnames as Capelthorne-Montbeau—a symbol of unity after centuries of conflict.

Flo thrives in her new home, tending her garden and visiting Bridget’s newly erected memorial, while Roman ensures that Capelthorne’s remains open under fair terms. The bookshop, reborn under new management, becomes a shared symbol of peace between two families once divided by pride.

By the end, The Battle of the Bookshops celebrates endurance, reconciliation, and the quiet triumph of love over rivalry. What began as a story of competition grows into one about belonging and renewal—where old books, small towns, and unlikely relationships remind us that even the fiercest battles can end in harmony.

Characters

Jules Capelthorne

Jules Capelthorne stands at the emotional and moral center of The Battle of the Bookshops. Initially depicted as a driven yet disillusioned publishing assistant in London, she is caught between professional exhaustion and deep-seated guilt over abandoning her roots.

Her journey back to Portneath becomes both literal and symbolic—a return to authenticity and self-discovery. Jules begins as someone shaped by the urban grind, under the oppressive thumb of Caroline Farquarson, but as she reconnects with her family and community, she sheds the superficial ambitions of city life.

Her evolution is underscored by a fierce sense of loyalty—to her great-aunt Flo, to the legacy of Capelthorne’s Books, and eventually to her own ideals. Throughout the story, Jules embodies resilience and defiance.

Her rivalry with Roman Montbeau channels her latent strength, while her eventual forgiveness of him reveals her capacity for emotional maturity. By the novel’s conclusion, she represents renewal—of love, legacy, and purpose—anchoring the emotional transformation of both families.

Roman Montbeau

Roman Montbeau is Jules’s foil and romantic counterpart, embodying the tension between tradition and progress. A man of privilege who initially views business as a competitive game, he returns from New York hardened by corporate ambition but inwardly conflicted.

His decision to open The Portneath Bookshop opposite Capelthorne’s demonstrates both arrogance and longing—for control, legacy, and perhaps connection. Roman’s charm, intellect, and latent decency complicate his role as antagonist; his moral conflict deepens as he falls in love with Jules.

Torn between filial duty to his father, Henry Montbeau, and his conscience, Roman evolves from a calculating businessman into a compassionate partner willing to dismantle his family’s ruthless legacy. His journey mirrors Jules’s—both seek redemption from inherited feuds and personal pride.

Roman’s final choice to preserve Capelthorne’s instead of profiting from its demise signifies his ultimate growth: love and empathy triumph over lineage and power.

Aunt Flo Capelthorne

Flo Capelthorne, with her plastered limbs and undimmed spirit, represents endurance and the warmth of tradition. The heart of the Capelthorne family, she bridges the past and present, nurturing both her niece and the struggling bookshop that symbolizes their shared history.

Flo’s gentle humor, emotional intelligence, and quiet strength provide moral grounding amid chaos. Her faith in books as vessels of connection contrasts with the commercial strategies surrounding her.

The subplot of her tender relationship with Graham adds poignancy and hope, showing that love and new beginnings can flourish at any age. Flo’s eventual purchase of Hollyhock Cottage and her stewardship of Bridget Capelthorne’s memory complete her arc—she becomes the guardian of the family’s physical and emotional heritage, embodying the endurance of goodness across generations.

Maggie Capelthorne

Maggie, Jules’s mother, is a portrait of imperfection and emotional distance. Self-absorbed and dramatic, she initially appears as an obstacle rather than a comfort.

Her fractured relationship with Jules stems from neglect, secrecy, and jealousy, particularly surrounding her late lover Alistair, whom she believes to be Jules’s father. Yet beneath her vanity lies vulnerability—a woman shaped by lost dreams and guilt.

Maggie’s gradual softening, culminating in her apology and small gestures of reconciliation, reflects one of the novel’s subtler redemptive threads. She embodies the complex, often flawed nature of maternal love: inconsistent, self-centered, but not entirely devoid of care.

In a story about legacy, Maggie’s emotional evolution underscores the possibility of forgiveness within even the most strained family bonds.

Freya

Freya provides a bright, effervescent counterpoint to Jules’s seriousness. As Jules’s childhood best friend and now a successful pastry chef, she symbolizes rooted joy and local belonging.

Her café, Freya’s, becomes a space of warmth and laughter, contrasting with the sterile competitiveness of London publishing or the glossy façade of The Portneath Bookshop. Freya’s engagement to Finn, her honesty, and her occasional missteps—such as unwittingly collaborating with Roman’s store—make her human rather than idealized.

Through Freya, the novel celebrates friendship as a form of sustenance; she reminds Jules of who she was before ambition and guilt clouded her identity. Freya’s nurturing spirit and loyalty lend balance to the novel’s central tension between rivalry and reconciliation.

Charlie

Charlie is one of the most distinctive and refreshing presences in the narrative—a nonbinary PhD student whose enthusiasm for antiquarian books injects youthful energy and intellectual curiosity into Capelthorne’s. Their meticulous cataloging of the shop’s forgotten treasures and discovery of the seventeenth-century grimoire catalyze both the plot and the thematic exploration of legacy.

Charlie bridges the past and future: they honor the value of history while employing modern tools like online sales to sustain it. Their friendship with Jules transcends age and hierarchy, offering mutual respect and encouragement.

Charlie’s arc, culminating in a Sotheby’s internship, symbolizes the reward of passion and integrity, and their gender identity, treated naturally and respectfully, enhances the book’s inclusivity without defining their character entirely.

Henry Montbeau

Henry Montbeau embodies the cold logic of old money and corporate power. As patriarch of the Montbeau family, he treats business as warfare and tradition as entitlement.

His insistence on reclaiming Capelthorne’s property despite its sentimental value reveals both cruelty and fear—fear of losing dominance in a world shifting toward empathy and collaboration. Henry’s exchanges with Roman expose generational conflict: the older man equates success with control, while his son seeks meaning through compassion.

Though he never truly redeems himself, Henry’s rigid worldview provides essential contrast to the emotional evolution of others. He represents the dying breed of industrial paternalists—formidable yet out of step with the humane future the younger generation envisions.

Graham

Graham, the widowed customer who slowly courts Flo, offers quiet emotional grounding. His progression from timid visitor to loving companion parallels the novel’s theme of renewal.

Graham’s gentle persistence and genuine affection contrast sharply with the ambitious energy of other characters. His romance with Flo exemplifies understated tenderness—proof that intimacy and trust can blossom later in life.

Through Graham, the story softens its focus from rivalry to companionship, suggesting that love, like literature, endures when nurtured with patience rather than spectacle.

Bridget Capelthorne

Though centuries removed, Bridget Capelthorne’s presence haunts the narrative like an ancestral echo. Her story—of persecution, misunderstood healing, and execution as one of England’s last accused witches—embodies the novel’s exploration of legacy, female resilience, and the reclamation of silenced voices.

The discovery of her grimoire transforms her from a tragic myth into a symbol of defiance. Bridget’s fate mirrors Jules’s struggle: both women stand against systems that misinterpret strength as rebellion.

In bringing Bridget’s story to light, Jules restores dignity to her ancestor and, by extension, to herself and the generations of women who refused to yield to oppression.

Themes

Family Legacy and Heritage

Family legacy drives every emotional and moral decision in The Battle of the Bookshops, shaping Jules Capelthorne’s journey from weary assistant to independent woman. Her return to Portneath isn’t only prompted by duty toward her injured aunt but also by a deep-seated pull toward the history embodied in Capelthorne’s Books.

The shop, run by generations of her family, becomes the symbol of continuity, endurance, and belonging. Through Jules’s eyes, legacy transforms from a burden of obligation into a living thread that connects past and present.

Flo’s dedication to keeping the shop alive represents a devotion that transcends commerce—it becomes an act of remembrance and identity preservation. The discovery of the seventeenth-century grimoire by Bridget Capelthorne adds a haunting layer, turning the family’s heritage into a mirror of women’s historical struggles for recognition and survival.

Bridget’s tragic execution as a so-called witch highlights how society often punished capable women who dared to exist beyond defined roles, and her rediscovered story allows Jules to reclaim strength from ancestral pain. Even Roman, though a Montbeau, is constrained by his own family’s heritage—pressured to perpetuate a feud he doesn’t fully believe in.

The contrast between the Capelthornes’ nurturing legacy and the Montbeaus’ mercantile dominance underscores how family inheritance can either bind or liberate. Ultimately, Jules’s defense of Capelthorne’s Books isn’t just about saving a shop; it’s about protecting memory, restoring justice to her bloodline, and redefining what it means to inherit something of worth.

Rivalry and Reconciliation

The longstanding feud between the Capelthornes and Montbeaus encapsulates the destructive persistence of inherited grudges. What began as a historical quarrel has calcified into a defining characteristic of both families, dictating loyalties, fears, and relationships across centuries.

When Jules confronts Roman’s rival bookshop, the ancient hostility manifests in modern competition—marketing battles, social charm offensives, and moral conflict over community loyalty. Yet beneath the rivalry lies an exploration of reconciliation: the question of whether individuals can rewrite the animosities imposed by history.

Jules and Roman’s evolving relationship becomes the emotional lens through which this theme unfolds. Their personal affection repeatedly clashes with family expectations, revealing how reconciliation demands courage, vulnerability, and the willingness to see beyond inherited narratives.

The rivalry between their bookshops mirrors the tension between old and new values—tradition versus progress, intimacy versus ambition. The turning point comes not through victory in competition but through mutual recognition of shared humanity and the futility of division.

When Roman ultimately chooses compassion over conquest, allowing Capelthorne’s to survive, the story suggests that true reconciliation is achieved not by erasing history but by confronting it with empathy. The families’ eventual peace demonstrates that love and understanding can heal generational wounds, replacing the cold inheritance of rivalry with the warmer legacy of unity.

Ambition, Identity, and Fulfillment

Jules’s personal evolution forms the emotional core of The Battle of the Bookshops, charting her transformation from a subordinate employee to an autonomous, fulfilled woman. Her early life in London symbolizes the hollow pursuit of professional success detached from purpose.

Working under a tyrannical boss in an industry that values appearance over passion, Jules loses sight of her own ideals. Returning to Portneath forces her to reexamine what ambition truly means.

The struggle to save Capelthorne’s becomes not just a business mission but a process of reclaiming identity and meaning. Through rediscovering her roots, Jules learns that ambition grounded in authenticity carries greater worth than advancement built on pretense.

The revival of the bookshop parallels her inner renewal—each decision to modernize, connect with customers, and protect its history reflects her growing confidence. Roman’s character provides a counterpoint: his corporate success and wealth have come at the cost of emotional satisfaction, and his attraction to Jules stems partly from her sincerity and purpose.

Their differing paths reveal that fulfillment arises when ambition aligns with personal truth. By the novel’s end, Jules’s triumph isn’t measured by wealth or acclaim but by self-realization—the recognition that success lies in belonging, love, and integrity rather than external validation.

Love as Transformation

Romantic love in the novel operates not as escape but as confrontation—it forces both Jules and Roman to face the contradictions within themselves and their families. Their relationship begins in hostility, shaped by past embarrassment and entrenched prejudice, but gradually exposes their vulnerabilities and shared longing for something real beyond rivalry.

Love here acts as a disruptive force, challenging inherited loyalties and societal boundaries. Jules’s affection for Roman demands forgiveness and the courage to see him apart from his surname, while Roman’s devotion compels him to defy his father’s expectations and abandon ruthless ambition.

Their bond evolves through tension, misunderstanding, and betrayal, culminating in a partnership that is built on honesty and mutual respect. What makes their love transformative is its refusal to ignore pain—it acknowledges deceit, broken trust, and generational curses, yet persists as an act of rebuilding.

By the conclusion, love doesn’t simply unite two individuals; it reconciles communities, heals old feuds, and restores hope. It turns the battlefield of bookshops into a shared future of cooperation.

In this way, love becomes the narrative’s moral resolution—a testament to how human connection can reshape even the most fractured histories and give meaning to loss, legacy, and redemption.

Feminine Resilience and Empowerment

Throughout The Battle of the Bookshops, women form the backbone of endurance, vision, and quiet revolution. The story’s emotional power resides in its portrayal of female agency across generations: Flo’s pragmatic optimism, Jules’s tenacity, Freya’s loyalty, and even Bridget Capelthorne’s posthumous voice collectively affirm the resilience of women who refuse to vanish into history’s margins.

The novel critiques the systems—corporate, familial, and patriarchal—that dismiss women’s labor and creativity as secondary. Jules’s former boss, Caroline, embodies that same system’s cruelty, reinforcing how even successful women can perpetuate oppressive hierarchies.

Against this backdrop, the Capelthorne women redefine success on their own terms, prioritizing community, authenticity, and compassion. The rediscovered story of Bridget’s persecution functions as both a cautionary tale and a symbolic inheritance—an ancestral warning about the price of female independence.

Jules’s decision to honor Bridget with a memorial signifies her reclaiming of narrative authority for women silenced by history. The intertwining of business survival with personal empowerment demonstrates that their struggle is never just economic; it’s existential.

Each step Jules takes—from cleaning shelves to negotiating with Roman—echoes generations of women fighting for recognition. By the novel’s end, her triumph is collective, carried by the voices of those before her, proving that empowerment flourishes not in isolation but through shared courage and memory.