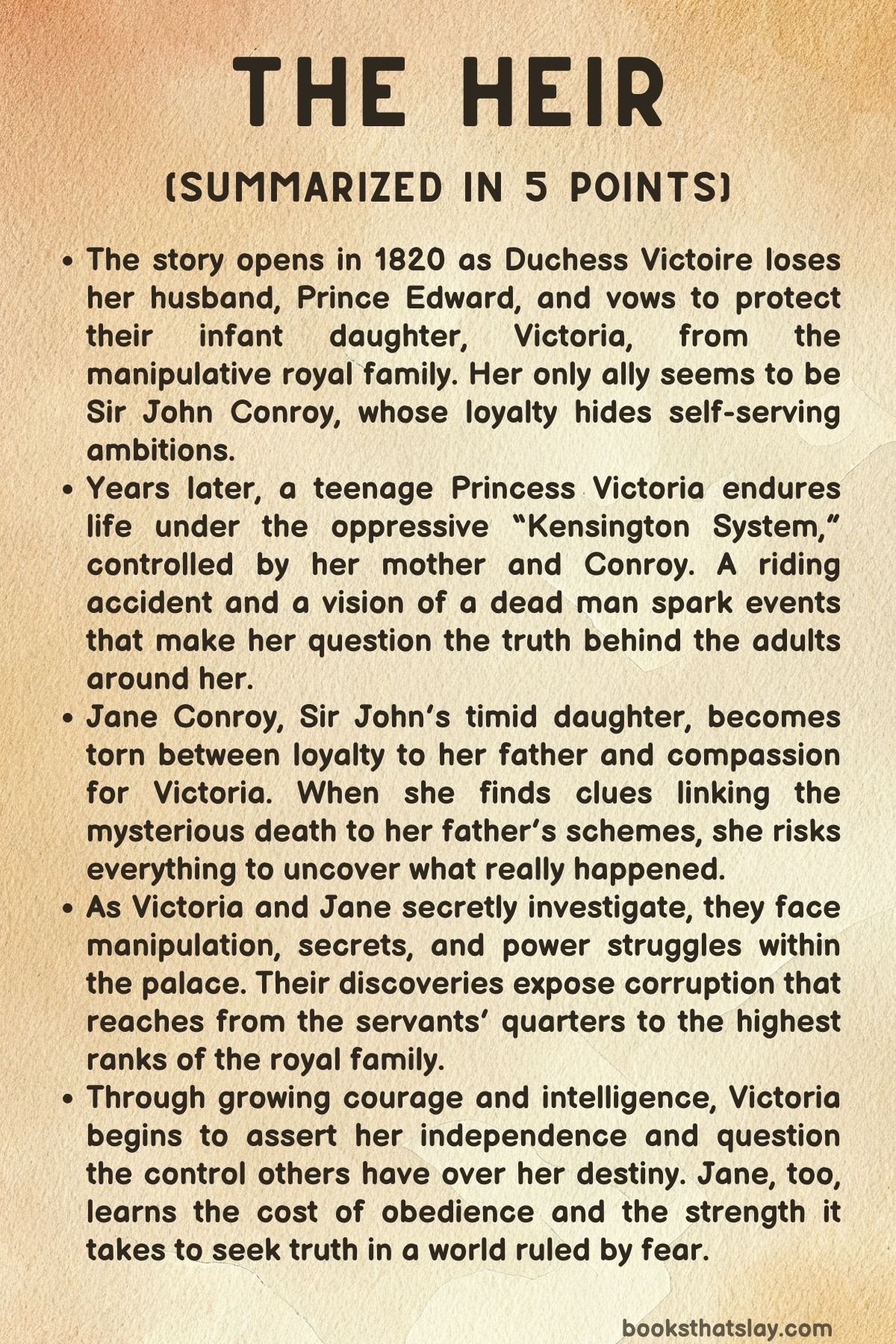

The Heir by Darcie Wilde Summary, Characters and Themes

The Heir by Darcie Wilde is a richly layered historical novel that blends royal intrigue, personal rebellion, and the shadowed politics of early 19th-century England. Set around the childhood and adolescence of Princess Victoria before she became queen, the story explores her life under the rigid “Kensington System” designed to control her every movement.

Told through the perspectives of Victoria and Jane Conroy, daughter of the domineering Sir John Conroy, the novel reveals a world of secrets, manipulation, and ambition within the royal household. At its core, it is a story about power—how it is gained, withheld, and reclaimed by those born into its orbit.

Summary

The novel opens in 1820 in the seaside town of Sidmouth, where Victoire, Duchess of Kent, keeps vigil beside her dying husband, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent. Outside, a fierce storm rages as their infant daughter, Alexandrina Victoria, cries in another room.

Edward, weakened by fever after exposure to the rain, is attended by Dr. William Maton.

Despite Victoire’s desperate prayers, the duke dies, leaving his widow and their baby in a vulnerable position within a hostile royal family. Before his death, he urges his wife to trust his aide, John Conroy, and to protect their child from the scheming of his brothers.

His death marks the beginning of Victoire’s dependence on Conroy, who quickly becomes her adviser and manipulates her loneliness and fear to consolidate his power.

Fifteen years later, Princess Victoria lives in seclusion at Kensington Palace under a strict regimen known as the “Kensington System,” enforced by her mother and Sir John Conroy. She is never left alone, every detail of her life monitored.

Her only comfort lies in moments of rebellion. During one such moment, she insists on riding her horse, Prince, in defiance of orders.

Accompanied by Jane Conroy, Sir John’s timid daughter, and the groom Hornsby, Victoria gallops across the park until her horse rears and throws her. Dazed, she glimpses what appears to be a dead man nearby—a bald man in a black coat—before fainting.

Back at the palace, her mother panics, fearing illness will take her daughter as it did her husband. Conroy arrives and strikes Jane for carelessness, but Victoria defends her companion and insists she saw a corpse.

The claim is dismissed as delusion, a product of her supposed hysteria. Only Jane believes her.

Later, Jane secretly returns to the site and discovers broken gold-rimmed spectacles buried in the mud. She hides them, suspecting they belong to the man Victoria saw.

Her father’s threats and manipulation force her silence, even as she realizes Conroy’s ambitions revolve around controlling Victoria’s future reign.

At the same time, Victoria begins to question the world around her. She senses deception in the adults governing her life.

Her governess, Lehzen, becomes her quiet ally, offering compassion and cautious guidance. When Victoria again mentions the body, Conroy claims to have found nothing.

Yet Jane’s discovery of the spectacles deepens the mystery. The princess’s insistence that she saw a dead man, and her growing awareness of Conroy’s lies, marks the start of her defiance.

The story then follows both young women as they navigate the dangerous undercurrents of palace life. Jane struggles under her father’s domination while yearning for approval.

Lehzen, suspicious of Conroy’s control, investigates the sudden dismissal of Hornsby, the groom who witnessed the fall. Her inquiries suggest that Sir John has concealed something about the dead man’s identity.

At a concert soon after, Conroy publicly claims the body was a gardener who died naturally, turning Victoria’s supposed “error” into a scene of humiliation. But Aunt Sophia, another royal, interrupts and accuses him of lying, creating uproar.

The outburst convinces Victoria that something is being hidden.

As political tensions grow, Victoria and Lehzen learn that Parliament may soon grant the princess her own household, freeing her from her mother and Conroy. This hope fuels Victoria’s determination to uncover the truth.

In a rare moment of courage, Jane confides that she found spectacles at the scene. Victoria recognizes them as Dr. Maton’s—the same physician who attended her father’s death. This revelation proves the dead man was not a gardener.

The two young women form a secret alliance to investigate, despite the danger of defying Sir John.

Their investigation uncovers a pattern of deceit. Dr. Maton’s sudden death and Sir John’s involvement raise suspicions of blackmail and political secrets. To learn more, Victoria secretly disguises herself and visits Dr. Maton’s son, Gerald, under the alias “Miss Kent. ” He tells her his father died mysteriously after a “gentleman” arranged hush money for the family and ordered his papers destroyed.

The princess begins to suspect that her father’s old physician was silenced to conceal royal corruption.

Meanwhile, King William IV rages against Conroy’s influence over the Duchess and demands that Victoria be granted her independence. But Parliament hesitates, and Conroy works tirelessly to maintain his control.

Victoria’s secret meetings and growing resolve strengthen her sense of identity as a future monarch. Lehzen remains her steadfast protector, warning her that power requires vigilance and mistrust of easy loyalty.

The balance shifts when Victoria is sent on a royal tour designed to showcase her loyalty to her mother and to delay the establishment of her household. On the journey, Conroy continues his psychological warfare, waking her at dawn and demanding that she sign a declaration naming him her private secretary.

He withholds food and comfort to force compliance. Victoria’s health deteriorates, and in a feverish confrontation she accuses him of poisoning both Dr. Maton and herself. She collapses soon after.

At the same time, Jane and her sister Liza rush to Ramsgate with help from a loyal maid and a coachman, carrying a doctor to rescue Victoria. Dr. Clarke diagnoses typhoid rather than poisoning, and Victoria slowly recovers under Lehzen’s care. Conroy spreads false reports of her improving health, using her illness to delay any political changes that would remove his authority.

During her recovery, Victoria and Jane piece together the remaining fragments of the mystery surrounding Dr. Maton’s death.

They discover that Dr. Maton had been writing a memoir filled with secrets about his powerful patients, using it to blackmail them for money.

The revelation points suspicion toward Lady Conroy—Jane’s mother—who often hosted private gambling gatherings and may have poisoned the doctor to protect herself. With evidence from a maid named Betty, Victoria confronts Lady Conroy and forces her into exile in Ireland.

Jane’s brother Ned is sent away as well, saving him from possible prosecution for his role in covering up the death. Lady Conroy admits that Sir John had bribed the Maton family to destroy incriminating papers, revealing his desperation to conceal his own scandals.

After this confrontation, Victoria regains strength and authority. She rejects further manipulation from her mother, who continues plotting her daughter’s marriage to secure influence.

With Lehzen, Jane, and other loyal allies, Victoria commits to protecting herself and preparing for the throne. The conspiracy around Dr. Maton fades into history, but its lesson endures: deceit and ambition can fester even in the gilded corridors of royalty.

In the final pages, the story circles back to 1820, revealing the moment Sir John Conroy first inserted himself into the Kent household. As the Duke of Kent lies dying, Conroy bribes Dr. Maton with banknotes to “do whatever you can. ” The doctor returns to bleed the duke once more, sealing his fate.

Watching from the shadows, Conroy turns toward the nursery where baby Victoria sleeps, already plotting the power he will one day claim through her. The scene closes the circle, showing how one act of opportunism would shape a generation of secrets and define the destiny of England’s future queen.

Characters

Princess Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria)

At sixteen, Victoria is the moral and narrative center of The Heir, emerging from the suffocating “Kensington System” with a will sharpened by constant surveillance. She learns to master performance: outward docility conceals an exacting memory, political intuition, and a private resolve to test every assertion made by her keepers.

The accident on the green jolts her into detective-like agency; she refuses to recant what she saw, assembles allies, and orchestrates a clandestine visit to Gerald Maton. Victoria’s sense of justice fuses with nascent statecraft—she frames the Maton mystery not merely as personal peril but as a question of public order under a future reign.

Ghostly visitations function like an inner council rather than superstition, reminding her to observe, to bide her time, and to turn fear into discipline. By the end, even in illness and political setback, she has learned the essential arts of monarchy: choosing confidantes, managing appearances, and striking when evidence will do the most good.

Victoire, Duchess of Kent

Victoire is a woman broken open by bereavement and fear, clinging to control as a surrogate for safety. Her love for her daughter is real, but it is braided with anxiety, status insecurity, and a dependence on the man her dying husband told her to trust.

That dependence curdles into complicity as she allows Sir John to define reality inside Kensington, dismissing Victoria’s perceptions as delirium when they threaten the regime that protects her. Victoire’s deepest conflict is between maternal instinct and political survival; at crucial moments she chooses the latter, not from malice but from terror of losing place, income, and relevance.

Her tragedy is that the methods she believes will preserve her family instead estrange her from the daughter whose ascendancy could secure them both.

Sir John Conroy

Sir John is the book’s most sophisticated antagonist, a courtier who wields intimacy as bureaucracy and menace as paternal concern. He choreographs theater—public apologies, whispered rumors, staged denials—to fix the narrative and isolate Victoria.

In private he is a domestic tyrant, striking his daughter, gaslighting the princess, and deploying hunger, exhaustion, and forced signatures as instruments of policy. His power rests on three habits: turning care into custody, laundering self-interest through constitutional language, and erasing evidence.

Yet his very competence exposes him; the tighter he draws the net, the more witnesses he creates. Even when he survives scandal by deflection, the coalition of women and servants he discounted have learned his patterns and begun to map the cracks.

Jane Conroy

Jane begins as a trembling satellite in her father’s orbit, desperate for a word of approval, and becomes the story’s most poignant study in divided loyalty. She pockets the spectacles that prove the corpse’s identity, lies by omission to stay safe, then edges toward courage as Victoria treats her not as a tool but as a partner.

Jane’s growth is measured in small rebellions—returning to the green, sharing the evidence, borrowing her own voice in a drawing room built to silence her. Her allegiance re-roots from blood to conscience without renouncing pity for her family; she negotiates the removal of her mother and the safety of her brother with a tact learned from watching power up close.

In a world that discounts her, Jane learns the leverage of information and the dignity of choosing the right risk.

Louise Lehzen

Lehzen is the quiet architect of Victoria’s autonomy, a governor who teaches vigilance before grammar and strategy before sentiment. She refuses bloodletting, resists panic, and understands the court’s true currency is access.

With servant networks, coded letters, and precise timing, she makes room for the princess to act without ever pushing her beyond prudence. Lehzen’s creed—watch, fight, trust sparingly—becomes Victoria’s operating system.

She is not a zealot; she considers abandoning the inquiry when it endangers her charge, and that hesitation proves her devotion is to Victoria’s future rather than to any vendetta.

Dr. Maton

Maton is both victim and catalyst. As a physician steeped in outdated cures and private vices, he personifies a decaying order: bleeding as treatment, gambling as pastime, secrets as revenue.

The shattered spectacles and the hush-money pension sketch a man ensnared by debts and tempted into leverage. Whether poisoned or simply overtaken by circumstance, his death exposes how gossip, medicine, and money intertwine at court.

He is culpable in his own way, but the moral weight falls on those who exploit his fall to tighten their control.

Dr. Gerald

Gerald inherits neither his father’s vices nor his influence; he brings candor and a willingness to help despite burned papers and purchased silences. His house becomes a neutral ground where Victoria, under an alias, discovers the power of direct inquiry.

Gerald’s letters move the investigation forward while underscoring how quickly truth can be extinguished when evidence is destroyed.

King William IV

The king supplies a counterweight to Kensington’s domestic despotism. Blunt and furious, he sees Conroy’s overreach clearly and pushes for Victoria’s independent household.

His power, however, is fettered by Parliament and protocol; his roar shakes doors but not always the hinges. He embodies a dying order’s rough honesty, more ally than mentor, yet decisive enough to remind everyone that legitimacy still has a voice.

Queen Adelaide

Adelaide moves in the corridor where conscience meets constraint. She grasps the peril of rumor and the limits of a queen consort’s agency, managing information to prevent panics that would strengthen Conroy.

Her cooled friendship with Victoire adds human texture to the political chessboard, showing how grief, rivalry, and prudence can harden into distance even among those who might have stood together.

Princess Sophia and the Duke of Sussex

Sophia’s public slap and Sussex’s studied calm reveal a sibling pair who know more than they say. Their rooms are a vault of withheld truths; their silence is both protection and indictment.

Sophia’s sudden reversal—from denunciation to forgetfulness—demonstrates how fear and faction can make honesty flicker, while Sussex’s placidity suggests a man who counts costs before choosing sides.

Lady Conroy

Lady Conroy presents as languid and careless, but beneath the indolence lies a calculator’s mind. The card table is her stage and her income stream; hospitality becomes a weapon when a teacup turns lethal.

She will sacrifice servants, break china, and accept exile if it preserves the family’s solvency and her son’s skin. In admitting the burning of Maton’s papers, she claims no innocence, only competence—the ethics of survival in miniature.

Liza Conroy

Liza begins as a fashionable scold and ends as a practical sister. Heartache disillusions her, and Jane’s peril clarifies her values.

She steps forward to manage the household when her mother departs, proving that capability can bloom in inhospitable soil. Her loyalty is not blind; it is chosen, and it costs her comfort.

Ned Conroy

Ned is the family’s fuse—hotheaded, reckless, and easily used. His duel and proximity to Maton’s death make him an expendable piece in his father’s larger game.

The plan to spirit him away is less an absolution than an acknowledgment that some fires can only be contained by removing their tinder.

Clyde Hornsby

Hornsby is the working man who pays for telling the truth. Dismissed as insolent, he nonetheless helps at key moments, a reminder that power’s edicts are enforced by people who can refuse, stall, or assist.

His loyalty is quiet, his courage practical.

Dr. Clarke

Clarke embodies professional reform and ethical restraint. He rejects bleeding, names typhoid where others might see advantage in mystery, and refuses to trade collegial gossip for court favor.

His steadiness offers a clinical counterpoint to the superstition and showmanship around him.

William Rea

Rea, the accountant, is temptation given human form—he answers openness with information priced in flattery. His revelations about Maton’s planned memoir and hush-money economy expose the ledgers beneath the lace, where debts, secrets, and stipends balance a court forever on the verge of scandal.

Susan and Betty

These maids illustrate how history turns on unnoticed hands. Susan’s attendance allows disguises and interviews; Betty’s memory of smashed china and paid silence unlocks the confrontation that unseats Lady Conroy.

Their bravery is not rhetorical; it is the courage to notice, to remember, and to speak when offered protection.

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Edward’s deathbed frames the novel’s moral inheritance. His tenderness and poor medical counsel entwine love with fatal error, while his injunction to trust Conroy seeds the tragedy to come.

In leaving a legitimate heir, he secures the line but inadvertently consigns his wife and child to a steward who mistakes guardianship for ownership. His absence is the vacuum every other character rushes to fill, and the measure by which Victoria resolves to become the kind of sovereign who will never bleed the realm for the sake of custom.

Themes

Control, Surveillance, and the Architecture of Power

Every corridor, timetable, and conversation in The Heir is arranged to keep a young princess compliant and the adults around her indispensable. The Kensington System functions less like a household regimen and more like a political technology: surveillance disguised as parental prudence.

Victoria’s days are broken into lessons and supervised visits, her nights punctured by Sir John’s predawn demands for signatures. Even the horse ride that begins as a small, private assertion is immediately translated into a disciplinary crisis, with the fall treated not as accident but as evidence that she cannot be trusted with unsupervised movement.

Public scenes—Sir John’s theatrical apology at the concert, the carefully managed tour—serve the same purpose as the locked doors at Kensington: to stage reality so thoroughly that alternative versions cannot be entertained. Control also works laterally through chains of dependency.

Servants fear dismissal; Jane worries about her family’s standing and her brother’s fate; the Duchess relies on Sir John to interpret events and defend her from both gossip and the king’s anger. The effect is a closed loop where observation produces narrative, and narrative justifies further observation.

What makes this apparatus compelling is how often it borrows the language of care. Sir John presents himself as protector; the Duchess speaks of safety; even medical interventions are framed as necessary caution.

Yet the novel keeps showing what such “care” costs: a starved princess in Ramsgate, a governess forced into subterfuge to preserve her pupil’s basic dignity, a groom dismissed for insolence when he knows too much. Power here is not only who issues commands but who controls the frame—what counts as truth, what gets recorded, and who is allowed to be alone.

Female Agency Under Constraint

Agency in the book rarely arrives as open defiance; it takes the form of quiet logistics, coded speech, and strategic self-presentation. Victoria learns to perform docility to buy minutes of privacy; Lehzen sends letters under harmless pretexts and recruits allies from below stairs; Jane measures each risk against a lifetime of training that equates obedience with survival.

None of these women can simply refuse—money, lineage, and legal structures stand against them—so they cultivate smaller, resilient powers: the choice of companion, the timing of a walk, the concealment of a found object in a pink reticule. The escape to visit Gerald Maton exemplifies this gendered craft of action.

A decoy carriage, a borrowed dress, a trusted maid, and a careful pseudonym convert the limited resources of a cloistered girl into a targeted investigation. Even conversation becomes a tool.

Victoria and Jane speak of dogs and drawings while harvesting details from gardeners; a tea visit doubles as intelligence gathering with William Rea; “embroidery” provides cover for planning. The book resists sentimental portrayals of female solidarity by showing frictions—Jane’s fear of betraying the princess, the Duchess’s readiness to suspect madness in her daughter, Aunt Sophia’s abrupt retractions—yet it insists that collective action remains possible.

When women coordinate across class (Lehzen, Susan, Betty) and status (princess, governess, companion), they produce outcomes that formal authority cannot achieve, such as isolating Lady Conroy or protecting witnesses. Agency, then, is less a heroic gesture than a sustained practice of attention and alliance, calibrated against the constant risk of reprisal.

The result is an ethic of action that is patient, tactical, and no less transformative for being quiet.

Gaslighting, Narrative Control, and the Fabrication of Truth

The contested corpse on the green is the novel’s early seminar in truth-making. Victoria insists she saw a bald man in a black coat; Sir John announces that nothing was there; moments later he supplies a replacement story—a gardener who died peacefully.

The speed with which an alternative narrative appears, complete with tone of authority and public apology, reveals how gaslighting operates: deny the witness, impose a more convenient version, and force the target to explain herself until her confidence erodes. The demand that Victoria erase a journal entry is the tactic’s purest form—control the record and the past itself becomes malleable.

Gaslighting here is not only psychological; it is administrative and performative. Dismissals are engineered; letters are composed for public audiences; even madness is floated as hereditary taint, converting a young woman’s perception into pathology.

Jane’s spectacles in the mud puncture this apparatus. Physical evidence—gold-rimmed, ribboned, unmistakably belonging to Dr.

Maton—reclaims the possibility of a shared, verifiable world. From then on, the contest shifts to documentation: papers burned, pensions arranged, servants paid off, reputations managed through gossip.

The novel shows how modern truth often needs infrastructure—postal routes for alias letters, discreet meetings, decoys—to survive against better-funded falsehoods. It also traces the personal toll: Victoria must second-guess her senses; Jane cycles between pride and dread; Lehzen risks her position to keep facts alive.

By the time Victoria confronts Lady Conroy with testimony secured beyond Sir John’s reach, truth is not a pure revelation but a negotiated victory, assembled from fragments before they can be erased. The book argues that in a court culture, truth is not found; it is defended.

Motherhood, Guardianship, and the Ambivalence of Care

Grief shadows the first pages: Victoire sits by a dying husband while a storm rattles the cottage and an infant cries in the next room. From that origin the story asks what maternal care becomes when survival requires political calculation.

The Duchess’s vigilance is real—she fears the royal brothers, she fears illness, she fears scandal—but her fear is easily recruited by Sir John into a regime that mistakes custody for love. Supervision stands in for intimacy; suspicion masquerades as prudence; the language of protection justifies a daughter’s isolation.

In counterpoint, Lehzen models another kind of guardianship, one that treats the child as a future ruler and a present moral subject. She comforts, yes, but she also teaches Victoria how to watch, to question, and to maintain a self that cannot be confiscated.

The conflict between these models plays out in bodies and documents: bleeding a feverish Duke versus refusing to bleed the princess; forcing an erasure in a journal versus preserving letters under an alias. The novel refuses a simple villain/saint division.

Victoire’s love is compromised but not counterfeit; she is also trapped by rank, gossip, and the king’s hostility, and her reliance on Sir John offers her a story in which she remains necessary. Yet the harm is undeniable: a daughter publicly inspected while still convalescing, a readiness to label her unstable, and a willingness to trade affection for control.

Motherhood, in this world, is tested not by feeling but by whether it enables the child’s moral growth. Lehzen passes that test by backing the investigation at personal cost; the Duchess fails by equating obedience with safety.

The question the book leaves hanging is whether maternal love can be repaired once it has been fused to ambition.

Coming of Age and the Education of a Monarch

Victoria’s maturation is charted less through birthdays than through the skills she acquires: holding a room during a crisis, reading the motives behind scripted apologies, and converting private conviction into public decision. Early on, courage expresses itself in a gallop across wet grass; later, it appears as refusal to sign a predrafted letter while exhausted and hungry.

She learns that power requires managing appearances without surrendering truth, that allies are built patiently, and that mercy for subordinates can coexist with clear-eyed judgment of superiors. The trip to Gerald Maton under the name Miss Kent is a turning point because it compresses multiple lessons—risk calculation, trust in staff, and command of narrative—into a single afternoon.

Later, the confrontation with Lady Conroy shows a further evolution. Victoria now understands leverage: witnesses removed from retaliation, a scandal calibrated to scare the powerful, exit terms that protect innocents like Jane and Ned.

Even her handling of Aunt Sophia’s volatility demonstrates a budding statesmanship—she prevents an escalation while noting where secrets pool. The education is civic as well as personal.

Exposure to Parliament’s role, to the king’s temper, and to the Board’s inspections teaches her that monarchy in the nineteenth century is negotiated authority, reframed constantly by newspapers, rumor, and finance. By the end, she is not yet sovereign, but she has a sovereign’s habits: she listens, she remembers debts, and she keeps looking for “the cracks” where change can begin.

The lesson The Heir proposes is that a good ruler is formed not by ceremony but by the disciplined refusal to be mastered by other people’s scripts.

Secrecy, Scandal, and the Politics of Reputation

Dr. Maton’s shadowy afterlife drives the plot because it illuminates how secrets are manufactured, priced, and laundered.

A physician who drank and gambled accumulates stories he should not possess and converts them into leverage: a planned memoir, quiet shakedowns, debts covered by patrons who cannot risk daylight. Sir John attempts to domesticate this instability with payments and document destruction, but secrecy behaves like quicksilver; it migrates into other hands—Rea the accountant, servants who pour tea, a maid who hears a crash of china.

The book shows how scandal is both feared and used. Sir John’s public apology is meant to cauterize rumor by drowning it in spectacle; the king’s fury at Whitehall harnesses scandal against Kensington’s cabal; Victoria eventually threatens scandal as a tool to remove Lady Conroy without wrecking the realm.

Reputation emerges as currency. A princess must look healthy enough to delay her independence; a governess must appear unobtrusive while coordinating a clandestine network; a family name—Conroy—must remain respectable enough that ambitious doors stay open.

Because the economy of secrecy is collective, guilt often becomes distributive: who actually poisoned Maton matters less than who benefited from his silence and who helped erase his traces. By staging letters, fires, and closed-door meetings alongside concerts and tours, the novel argues that nineteenth-century politics are made as much in drawing rooms as in chambers of state.

The final terms offered to Lady Conroy are not courtroom justice but reputational settlement, a recognition that sometimes the safest outcome is a managed truth that prevents greater harm. In this ecosystem, virtue is measured by whom one protects when a secret breaks.

Class, Labor, and the Invisible Hands of the Palace

Behind every royal gesture stand workers whose livelihoods can be withdrawn with a word. Hornsby loses his post the moment his knowledge becomes inconvenient; gardeners are compelled to move a body and keep quiet; a footman is leaned on to carry a message despite the risk.

Betty and Susan, with access to rooms and teacups, hold pieces of the puzzle that titled figures cannot reach. Their testimonies, however, are negotiable because the class system renders them both ubiquitous and disposable.

The Heir insists on their agency without romanticizing their vulnerability. They notice things because labor requires attention; they trade information because survival requires calculation.

Jane’s position is especially telling. She moves between drawing rooms and servants’ corridors, translating elite intentions into household logistics.

Her fear of her father and love for her siblings tether her to a family whose advancement depends on her agreeable presence near the princess. When she speaks confidently to William Rea, she is not merely playing court lady; she is trying on a role that class may deny her, leveraging knowledge rather than rank.

The book uses these crossings to critique an order that praises loyalty while punishing initiative from below. Dismissal, slander, and starvation threaten workers into complicity, yet the plot’s moral arc depends on their courage.

Without their small acts—quiet rides in the rain, secret letters posted, a pair of spectacles pocketed—the powerful would keep their stories intact. By bringing these figures into focus, the novel reframes a palace as a workplace, where justice advances through the ethics of people whose names rarely appear in the bulletin.

Medicine, Mortality, and the Performance of Authority

From the Duke of Kent’s bleedings to the typhoid diagnosis in Ramsgate, medicine in the narrative is a theater where power and uncertainty exchange masks. Dr.

Maton practices within the period’s orthodoxies—leeches, bleeding, exhaustion—yet his authority is porous enough to be bought, suborned, and finally destroyed. Dr.

Clarke represents a cautious modernity, declining to bleed Victoria and rejecting gossip, but even he is drawn into the politics of access and appearances. Illness becomes a lever.

Sir John uses Victoria’s convalescence to postpone the creation of her household; the Duchess brandishes fear of inherited instability to impose stricter rules; public bulletins are crafted to reassure audiences less about health than about continuity. The dying Duke’s sickroom and the storm outside make bodily fragility the story’s first fact, yet the book refuses medical melodrama.

Instead, it studies how clinical decisions are narrated and who gets to narrate them. Was a death natural, accidental, or criminal?

The answer depends less on autopsy than on who controls servants, who pays sons to burn papers, and who can stage a respectable explanation. Medicine thus shares something with monarchy: both claim neutral expertise while being entangled with money and reputation.

When Victoria accuses Sir John of poisoning during a feverish collapse, the scene exposes the gendered dynamics of credibility—her words discounted, his insistence treated as rational. Clarke’s later diagnosis rescues her body but cannot by itself cure the political fever around her.

In the end, health in the book is both physical state and civic condition. A palace can keep breathing while still ailing, unless someone is brave enough to change its regimen.