The Hounding Summary, Characters and Themes

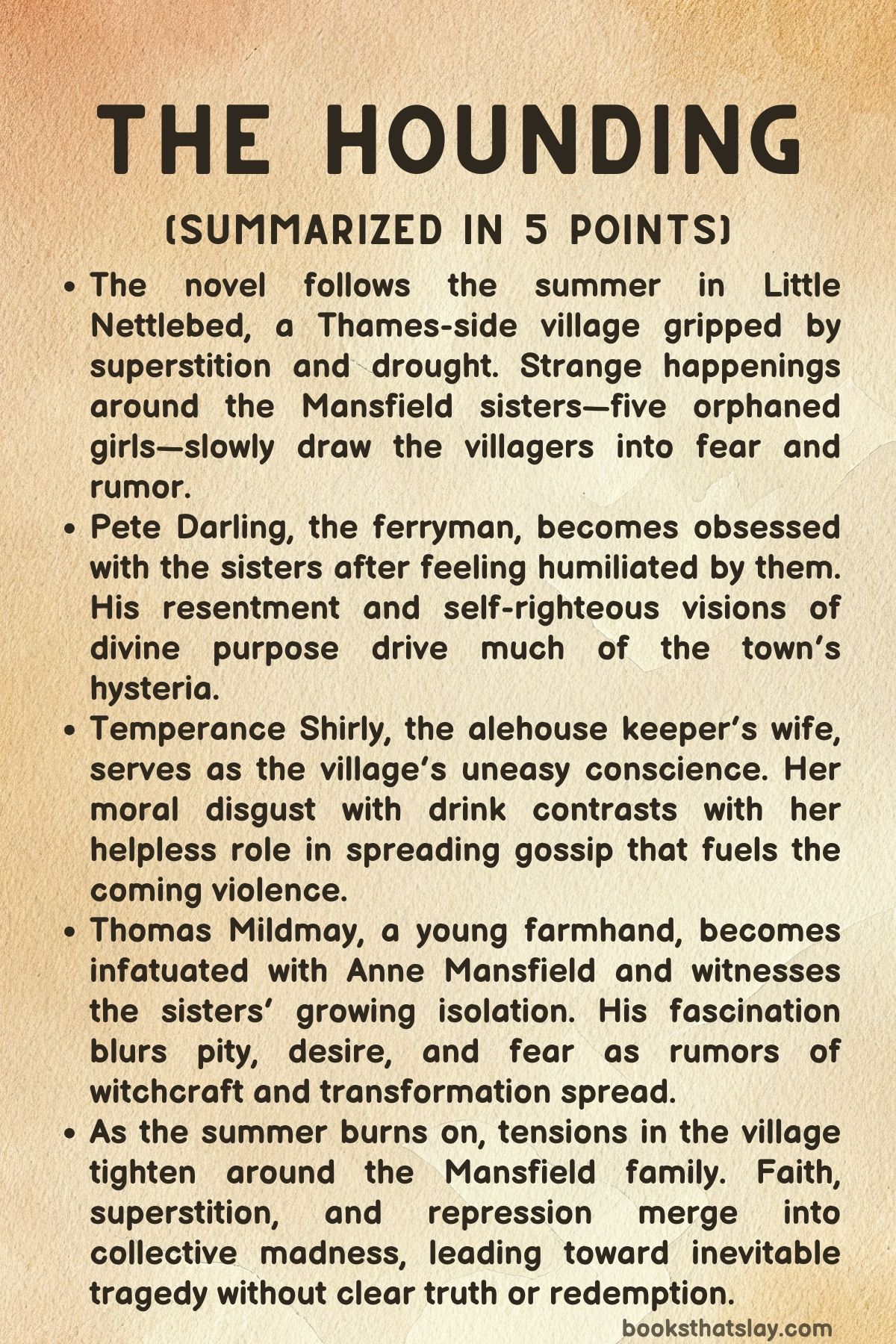

The Hounding by Xenobe Purvis is a haunting exploration of superstition, fear, and the human instinct to destroy what it cannot understand. Set in the English countryside during an oppressive summer, it follows the residents of Little Nettlebed, a village suffocating under drought and suspicion

At its center are the Mansfield sisters, five mysterious young women whose independence and beauty provoke both fascination and dread. As rumors spread that the sisters can turn into hounds, hysteria builds, exposing the villagers’ cruelty and the fragile line between belief and madness. Through intersecting voices, the novel captures a community collapsing under its own fears and moral decay.

Summary

The story begins with Pete Darling, a ferryman on the River Thames, who has inherited his trade from his father. Pete is a man torn between faith and resentment, spending his days drinking and imagining himself divinely chosen.

When he encounters the Mansfield sisters—five eerily composed young women known for their aloofness—his fascination quickly turns to anger. Their quiet disregard humiliates him, and he begins to brood over their defiance.

The summer grows hotter, the river recedes, and strange occurrences unsettle the villagers. When a massive sturgeon is caught in the river, the sisters’ attempt to return it to the water enrages the men.

Pete kills the creature in a drunken fury, an act that marks the beginning of the village’s descent into violence.

Temperance Shirly, the alehouse keeper’s wife, observes these changes with growing unease. Her distaste for drunkenness and superstition isolates her from the villagers, but she senses that something unnatural is stirring.

The oppressive weather, coupled with a series of deaths and accidents, deepens the community’s restlessness. Into this tense atmosphere arrives Thomas Mildmay, a young laborer seeking work at the Mansfield farm.

He is drawn to the family’s strange independence and, in particular, to Anne, the eldest sister. His curiosity soon becomes infatuation, and his awe turns to fear when he witnesses the sisters’ playful cruelty and secretive unity.

Old Joseph Mansfield, the sisters’ grandfather, senses unease in the land. Blind and aging, he clings to his faith and authority while the world around him seems to warp.

The dead sturgeon’s remains rot outside his gate, a symbol of decay spreading through Little Nettlebed. Pete Darling, meanwhile, becomes obsessed with the sisters, projecting his guilt and desire onto them.

Convinced that they represent sin and temptation, he begins to see them as enemies of divine order.

At the alehouse, the men’s talk turns darker. Cruel entertainments like badger-baiting reveal the village’s capacity for savagery.

Robin Wildgoose, a young farmhand, joins reluctantly, ashamed by his complicity. He and others feel trapped between moral conscience and the violent expectations of their peers.

When Pete’s drunken ramblings about the Mansfield sisters begin to circulate, the fragile balance of fear and fascination tips toward hysteria.

The story shifts one evening when Robin encounters Pete by the river after dark. Their tense exchange hints at hidden danger, and later, Robin meets two of the sisters on the road, warning them with a harshness he immediately regrets.

Moments later, he hears strange barking in the distance and glimpses Pete returning from their direction. The next day, rumors spread that Pete saw the sisters transform into dogs.

Temperance dismisses it as drunken nonsense, but gossip carries the story through the village. Even Pete’s fiancée, Agnes Bullock, spreads the tale, turning fear into certainty.

As the rumor festers, the village’s mood shifts from suspicion to hostility. Livestock are found slaughtered, and the sisters are blamed.

Robin, tormented by guilt and fear, recalls the barking he heard and wonders what really happened. Death visits again—a woman dies in childbirth—and the villagers interpret it as another omen.

Temperance, hoping to quell panic, confides in the vicar, but he instead decides to “help” the girls through prayer, worsening the tension.

Within the Mansfield household, the sisters grow increasingly restless. The unrelenting drought mirrors their own suffocating confinement.

Hester’s destructive energy contrasts with Anne’s stern composure and Elizabeth’s melancholy. Joseph Mansfield tries to protect them, but his authority falters as his faith in reason wanes.

When the vicar and Thomas both confess to seeing something strange in the girls’ faces, Joseph realizes that the rumor has taken on a life of its own. The villagers’ imagination has become more powerful than truth.

Thomas, frightened yet bound by fascination, decides to remain near the farm to shield the sisters. The doctor from Oxford arrives, diagnosing their condition as “hysteric disorders” rather than witchcraft.

His rational explanation does little to calm the village; instead, it confirms to many that the girls are afflicted by something unnatural. Joseph, desperate to keep them safe, confines them inside.

The maids flee, and the household becomes a prison.

Pete Darling, now unemployed as the river dries up, sinks deeper into madness. He believes himself chosen by God to expose evil, and when a boy tells him of dogs seen near the fields, Pete declares it proof of the sisters’ curse.

Temperance tries to intervene, but panic grips the men of Little Nettlebed. Murmurs of judgment and purification echo through the alehouse.

The novel’s final act unfolds during Pete’s wedding day—a day meant for renewal but tainted by drought and fear. Convinced of divine protection, Pete drinks heavily and walks to the riverbank, where he imagines seeing an angel once more.

Meanwhile, Joseph allows the sisters a brief moment of freedom in the orchard, unaware that the village is marching toward disaster. During the wedding, barking is heard outside the church, sending a chill through the congregation.

The crowd rushes out to find Pete bleeding by the river, claiming Anne Mansfield bit him. Spurred by his words, the villagers hunt the sisters.

Under a willow, the five sisters are discovered with Thomas Mildmay. Pete accuses them, Thomas defends them, and violence erupts.

Pete strangles Thomas until Robin, in a desperate act, stabs him with Hester’s knife. As Pete dies, he calls out for his angel, realizing too late the emptiness of his faith.

The sisters, Thomas, and Robin flee, but the villagers soon find Pete’s body and turn their fury on the Mansfields. Thomas falsely confesses to the killing to protect Robin and Anne, allowing himself to be bound and taken away.

Temperance, wrestling with her own moral collapse, breaks her lifelong abstinence and drinks heavily. Moved by guilt, she helps Thomas escape imprisonment by secretly leaving him a sharp shell to cut his bonds.

As the villagers prepare for vengeance, Joseph Mansfield plans to flee with his granddaughters at dawn. That night, he wakes to find the girls gone and glimpses, through the moonlight, five hounds and a boy running together across the fields.

In this vision—or reality—Joseph feels both grief and peace, sensing they have escaped the cruelty of Little Nettlebed. As rain finally begins to fall, he returns to bed, awaiting the mob that will soon arrive.

The novel closes on this image of release and renewal: the drought breaking, the sisters gone, and the village left to face its own sins. The Hounding becomes not just a story of superstition but an allegory of human fear—the relentless need to punish what cannot be understood, and the quiet resilience of those who refuse to submit to it.

Characters

Pete Darling

Pete Darling stands at the heart of The Hounding as a man consumed by resentment, delusion, and thwarted pride. A ferryman on the River Thames, he is both a product and a victim of his own superstition.

Haunted by his father’s tales of strange river visions and emboldened by his supposed sighting of an angel, Pete’s faith mutates into self-righteousness. His sense of divine favor masks deep insecurity and bitterness, particularly toward women.

The Mansfield sisters, whose composure and self-possession he cannot comprehend, become targets of his contempt. Pete’s violence and self-loathing feed off each other; his belief in divine purpose becomes justification for cruelty.

By the end, his mind is fully clouded by delusion—he imagines the sisters as shape-shifting hounds and himself as an agent of divine justice. His death at Robin’s hand is both an act of poetic justice and a grim commentary on hysteria and masculine fragility.

Temperance Shirly

Temperance Shirly embodies moral struggle and human frailty amid societal decay. As the alehouse keeper’s wife, she detests alcohol because it destroyed her father, yet she exists within its world daily.

Her rationality and compassion make her one of the few clear voices in Little Nettlebed. She senses the rising madness—the drought, the strange omens, and the villagers’ cruelty—and attempts to act as a moral counterweight.

Yet even she becomes complicit, when her well-intentioned conversation with the vicar helps unleash persecution against the Mansfield sisters. Her eventual succumbing to drink after Pete’s murder symbolizes her exhaustion and despair.

Temperance represents the conscience of the novel—someone who recognizes evil yet cannot stop it. Her character arc reveals the limits of reason and virtue when hysteria grips a community.

Joseph Mansfield

Joseph Mansfield, the aging patriarch of the Mansfield household, is a figure of tragic dignity and fading authority. Blind and weary, he clings to rationality and the traditions of the land even as the world around him unravels.

His love for his granddaughters is profound but conflicted—he wishes to protect them from gossip and harm, yet his efforts to confine them ultimately imprison them in fear. Joseph’s blindness functions symbolically; he cannot “see” the transformations in his family and community until it is too late.

His final vision of the sisters running as hounds, accompanied by Thomas, is both a hallucination and an act of release. In that moment, Joseph transcends his own limits, recognizing their freedom as something sacred and ungovernable.

His deathlike sleep afterward closes the novel on a note of quiet resignation.

Anne Mansfield

Anne Mansfield, the eldest sister, is the emotional and moral core of The Hounding. Reserved, intelligent, and fiercely protective of her siblings, Anne navigates the pressures of a patriarchal village that fears female independence.

Her self-control is misread as pride, and her beauty becomes a source of both fascination and suspicion. Anne’s relationship with Thomas Mildmay reveals her yearning for tenderness and escape, yet she remains bound by duty to her family.

The rumors of her transformation into a hound reflect how society demonizes female strength and sensuality. When she bites Pete in the final confrontation, the act is both literal and symbolic—an assertion of defiance against male violence.

Anne emerges as a figure of tragic empowerment, her story blurring the line between myth and human endurance.

Hester Mansfield

Hester Mansfield is the wildest and most volatile of the sisters, embodying youthful rebellion and the dangers of suppressed emotion. Her mischievous cruelty—tricking Thomas into the well or mocking village boys—masks deep insecurity and confusion about her own identity.

As she approaches womanhood, her behavior grows increasingly erratic, hinting at both fear and awakening desire. Hester’s “becoming a woman” parallels the village’s descent into hysteria: both are natural transformations misread as monstrous.

Her fascination with fire and her defiance against taunts make her a symbol of unrestrained vitality. Through Hester, the novel exposes how society punishes girls for their energy and curiosity, branding them as unnatural when they refuse to submit.

Thomas Mildmay

Thomas Mildmay serves as the novel’s outsider-observer, whose fascination with the Mansfield sisters turns to moral awakening. Initially naive and impressionable, he is drawn to Anne’s mystery but quickly becomes entangled in the villagers’ paranoia.

His compassion contrasts sharply with Pete’s violence; where Pete seeks to dominate, Thomas seeks to understand. Yet his love for Anne blinds him to danger, leading to his false confession to protect Robin.

His willingness to sacrifice himself illustrates his transformation from a passive bystander to a figure of quiet heroism. Thomas’s final escape with the sisters—whether literal or visionary—marks him as part of their mythic exodus, a companion in their liberation from human cruelty.

Robin Wildgoose

Robin Wildgoose is the moral pivot of the younger generation—a boy torn between empathy and the need to belong. His early attempts to mimic the rough masculinity of the village men reveal his insecurity, yet he remains sensitive to suffering.

Witnessing cruelty, from the badger-baiting to Pete’s harassment of the Mansfield sisters, leaves him increasingly disillusioned. His fatal stabbing of Pete is both impulsive and redemptive, an act of defense that also signals his loss of innocence.

Robin’s story mirrors the novel’s central tension: the struggle to retain humanity in a world consumed by fear. His bond with the sisters, particularly Anne, suggests hope for renewal beyond the boundaries of Little Nettlebed.

Anne, Elizabeth, Hester, Grace, and Mary

As a group, the Mansfield sisters—Anne, Elizabeth, Hester, Grace, and Mary—represent both mystery and resistance. They are portrayed as an unsettling unity, moving and thinking almost as one body, which fuels the villagers’ fear of the unnatural.

Their closeness becomes a shield against a world that seeks to define and control them. Each sister expresses a different facet of feminine experience—Anne’s strength, Hester’s rebellion, Elizabeth’s melancholy, Grace’s honesty, and Mary’s innocence.

Together they embody the novel’s central myth: women as both human and elemental, bound to the earth, misunderstood, and persecuted. Their rumored transformation into hounds becomes the villagers’ projection of guilt and desire—a supernatural expression of social repression.

In the final vision of their freedom, they transcend victimhood, merging with nature itself in defiant grace.

Themes

Superstition and Mass Hysteria

Superstition operates as a destructive force throughout The Hounding, exposing how fear can mutate into cruelty when collective paranoia takes hold of a community. The villagers of Little Nettlebed live in a world where religion, rumor, and folklore overlap so completely that the line between faith and delusion disappears.

When Pete Darling claims that the Mansfield sisters have transformed into dogs, his words take root in a soil already fertile with unease. The drought, the death of livestock, and the earlier appearance of the “angel” all become evidence that nature itself is conspiring to affirm his vision.

This fear of the supernatural grants legitimacy to hatred and turns ordinary gossip into mob justice. The villagers’ readiness to believe that five young women are cursed reveals their desperate need for an explanation that restores order to a world threatened by chaos.

Their hysteria is not born solely of ignorance but of the human craving for moral clarity—evil must have a face, and that face must be punished. As the story advances, hysteria spreads through every social layer: the vicar sanctifies it, men make it sport, and women whisper it into permanence.

By the time violence breaks out, the truth has become irrelevant. The rumor has replaced reality, transforming superstition into a weapon of control and moral panic that destroys both the accused and the accusers.

The theme ultimately reflects how communities, when governed by fear and rumor, lose their capacity for reason and compassion, turning faith into fanaticism.

Gender, Power, and the Fear of Female Autonomy

In The Hounding, gender dynamics shape the entire structure of oppression and violence. The Mansfield sisters represent independence, mystery, and self-possession—qualities that make them intolerable to a patriarchal society defined by male dominance and moral hypocrisy.

Men like Pete Darling and the vicar perceive their quiet defiance not as strength but as rebellion against divine and social order. Pete’s fixation on the sisters exposes the intersection of desire and hatred; his need to dominate women stems from the terror of losing control.

When he interprets their silence as mockery and their confidence as witchcraft, it becomes clear that female independence is perceived as an existential threat. The village’s reaction to the rumor of the sisters’ transformation into dogs further illuminates this dynamic: womanhood itself becomes monstrous when uncontained.

The supposed “curse” is merely a projection of male anxiety about female sexuality, power, and community. Even characters like Temperance Shirly, though morally strong, internalize the same fears, her guilt and restraint revealing how patriarchy polices women through piety and shame.

Anne Mansfield, by contrast, embodies resistance—she acts decisively, cares for her family, and refuses to flee her home despite danger. Yet her eventual transformation, whether literal or symbolic, underscores the impossibility of surviving unscathed in a society that punishes female strength.

Through this theme, the novel exposes how misogyny disguises itself as righteousness, turning fear of women into justification for cruelty and control.

Religion, Morality, and Corruption of Faith

Religious authority in The Hounding functions less as a source of guidance than as a mirror for human weakness. The villagers’ Christianity, filtered through ignorance and fear, becomes a justification for violence rather than compassion.

Pete Darling’s vision of an “angel” becomes the cornerstone of his self-righteousness; he interprets every impulse—lust, rage, guilt—as a divine message. The vicar, meant to offer spiritual leadership, instead amplifies panic by giving theological validation to superstition, turning moral duty into moral decay.

The result is a religion stripped of mercy, consumed by suspicion and punishment. This corruption of faith transforms divine belief into a mechanism for policing behavior and reinforcing social hierarchies.

The distinction between holiness and madness blurs—Pete believes his hatred is sanctified, while the villagers’ brutality takes the form of moral duty. Yet amid this decay, the story hints at an alternative spirituality rooted in empathy and connection to nature.

Joseph Mansfield’s quiet reverence for life and the sisters’ intuitive bond with the natural world stand in stark contrast to the village’s violent religiosity. The conflict between these two forms of belief—compassionate versus punitive—reveals how faith can either humanize or dehumanize, depending on whether it seeks understanding or control.

Ultimately, the novel portrays a world where religion, stripped of humility, becomes indistinguishable from hysteria, proving that morality without compassion is merely another form of corruption.

Isolation, Nature, and the Collapse of Order

Nature in The Hounding operates as both setting and symbol—a reflection of moral and social decay. The recurring images of drought, heat, and the dying river mark not only environmental crisis but also the breakdown of human order.

The village’s dependence on the river for survival mirrors its dependence on social cohesion; when the river dries, so does the community’s sanity. Isolation intensifies this collapse—each household becomes an island of suspicion, each individual consumed by private guilt and fear.

The Mansfield farm, lush and separate from the rest of Little Nettlebed, becomes both sanctuary and target, its fertility contrasting the village’s sterility. As the drought worsens, boundaries between human and animal blur; barking echoes in the night, and people begin to move with a feral desperation.

This merging of the natural and unnatural reflects a world sliding into primal chaos. Yet nature also holds the promise of renewal: Joseph’s final vision of his granddaughters running free as hounds coincides with the scent of approaching rain.

In that moment, destruction gives way to restoration—the wildness that society feared becomes the source of liberation. Through this theme, the novel suggests that human attempts to dominate nature, morality, and one another inevitably lead to ruin, and that only by accepting wildness—within the world and within ourselves—can renewal begin.

Violence, Guilt, and the Cycle of Retribution

Violence courses through The Hounding not as sudden eruption but as a slow contagion, growing from humiliation, envy, and fear. Every act of cruelty, from Pete’s abuse of the Mansfield sisters to the village’s badger-baiting, arises from the same impulse to assert control through destruction.

The story demonstrates how ordinary men justify violence by disguising it as justice or necessity. Pete’s final death at Robin’s hands completes a tragic cycle: the victim becomes aggressor, the innocent becomes killer.

This transformation underscores the novel’s bleak vision of morality—once violence is sanctioned by the community, it infects everyone, regardless of intent. Temperance’s relapse into drinking, the villagers’ mob rage, and even Joseph’s passive complicity illustrate that guilt spreads just as easily as rumor.

No one remains untouched. Yet the novel also acknowledges that violence can sometimes become the only language left to the powerless.

Robin’s act, though terrible, is born of desperation and moral conflict rather than hatred. His guilt, juxtaposed with Thomas’s false confession, reveals the complexity of human conscience—the need to atone even when justice itself is corrupted.

The story’s conclusion, where Joseph witnesses the girls’ final transformation and feels both grief and peace, suggests that the only escape from the cycle of violence lies in surrender, in accepting what cannot be purified or punished. Through this theme, the novel portrays violence not as aberration but as consequence, a reflection of a society that mistakes righteousness for cruelty.