The Housewarming Summary, Characters and Themes

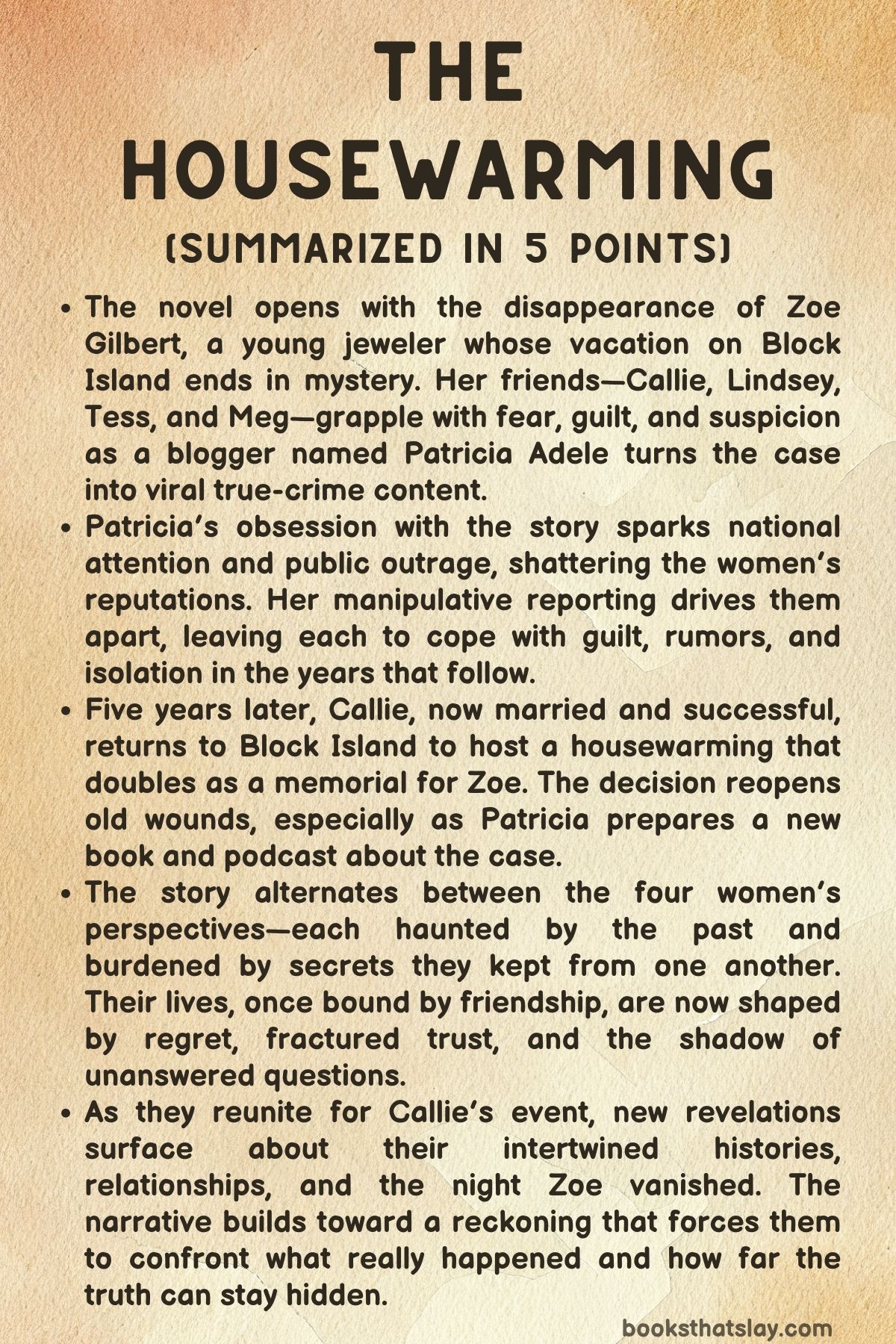

The Housewarming by Kristin Offiler is a psychological drama exploring the corrosive power of secrets, guilt, and public scrutiny. Set on Block Island, it follows four women—Callie, Meg, Tess, and Lindsey—whose friendship shattered after their friend Zoe disappeared five years earlier.

When Callie returns to the island and hosts a “housewarming” on the anniversary of Zoe’s vanishing, long-buried memories resurface, and the women must confront not only the past but also their own complicity in how truth was distorted. Through shifting perspectives and layered revelations, the novel examines how friendship, grief, and media obsession intertwine in the aftermath of tragedy.

Summary

In August 2014, Zoe Gilbert, a young jeweler visiting Block Island, vanishes without a trace after a stormy night. Her disappearance triggers an intensive search by volunteers and police, but after three fruitless days, it is Patricia Adele, a self-styled blogger fascinated by missing-persons cases, who discovers a pair of red heart-shaped sunglasses near Mohegan Bluffs.

Recognizing them from the missing posters, she alerts Zoe’s friends—Callie, Lindsey, Tess, and Meg—who react tensely and suspiciously. The police downplay the discovery, but Patricia senses that the group is hiding something.

When she is dismissed and mocked by the women, she begins documenting them for her blog, setting off a chain of events that will alter all their lives.

Patricia’s posts soon go viral. Through selective editing and emotional manipulation, she paints Zoe’s friends as secretive and possibly complicit.

The internet frenzy grows, with followers camping outside the house where the women are staying and chanting for justice. Patricia basks in the attention, convinced that one of them will eventually confess under pressure.

Her crusade marks the beginning of her rise as a true-crime influencer, exploiting grief for fame. Meanwhile, the women’s friendship begins to fracture under the scrutiny and the weight of their own guilt.

Five years later, Callie Sutter—once the confident leader of the group—is now married to Nathan and living a comfortable life after selling a mindfulness app. Yet she remains haunted by Zoe’s disappearance.

Against her husband’s reservations, she buys a house on Block Island, the very place of their trauma. She plans a housewarming on August 10, the anniversary of Zoe’s vanishing, intending to reconcile with her estranged friends and to hold a memorial.

But the decision revives old wounds. Locals still remember the case vividly; a woman at the market accuses Callie of hypocrisy, pointing to Zoe’s faded missing poster.

The reminder that her own televised interview years ago had fueled suspicion among the group fills Callie with dread. Her attempt at redemption threatens to reopen every scar.

Meg Bradley, now working in publishing, learns that Patricia Adele—who has become a bestselling podcaster—is preparing a new book on Zoe’s case. The revelation triggers panic and anger.

Meg recalls how Patricia’s harassment once destroyed their lives, stirring mobs and spreading false narratives. When Meg’s boss expresses interest in representing Patricia’s new project, Meg desperately tries to block it, knowing firsthand the damage Patricia caused.

Her anxiety deepens when she realizes Patricia has obtained materials that suggest new information about the night Zoe vanished.

Tess, the most tender and unstable of the group, now struggles with new motherhood. Sleep-deprived and isolated, she becomes obsessed with memories of Zoe, once her closest friend.

After mistaking a stranger for Zoe at the beach, Tess’s guilt and longing intensify. She follows Callie’s social media posts and eventually receives an unnerving message from Patricia asking for an interview, calling Tess “the most haunted” of them all.

Against her better judgment, Tess responds, unaware that Patricia is again manipulating the narrative for profit.

Lindsey, meanwhile, has fallen furthest. Living above a bar and drowning in debt, she supplements her income by going on paid dates with an older man, Fred.

Their arrangement is uneasy, but she finds comfort in the attention. When the old friend group reconnects over text—after Meg warns that Patricia’s book is imminent—Lindsey’s fragile life begins to unravel.

She remembers how she lied during the original investigation, claiming she went to bed early the night Zoe disappeared. In reality, she knew more than she ever admitted, and those lies now threaten to resurface.

When Lindsey learns that Callie is hosting a reunion on Block Island, she reluctantly agrees to attend. Before the gathering, she continues seeing Fred, gradually opening up about her past—until she discovers, to her horror, that Fred’s real name is Cameron Frederick Oakes, a man who once knew Zoe.

Hidden in his boat, she finds a photo of Zoe sitting on what looks like Callie’s parents’ yacht. Terrified, she hides the photo, unsure what it means.

As the anniversary approaches, the four women return to the island. The reunion is tense, fueled by alcohol, suspicion, and unspoken resentment.

They argue about Patricia’s manipulations, their fractured loyalty, and the interview that long ago turned the public against them. When night falls, Meg confides in Lindsey that Patricia’s manuscript accuses them of lying and includes witnesses who saw Lindsey that night, contradicting her alibi.

Lindsey panics, realizing Patricia’s investigation may expose more truth than she’s ready to face.

At the party, Callie reveals that her “housewarming” is actually a public vigil to relaunch the search for Zoe. She invites the Gilberts, Zoe’s parents, streams the event live, and pleads for tips and forgiveness.

Patricia crashes the vigil, claiming to have new witnesses and confronting the women publicly. Tess, humiliated after Patricia reveals their private meeting, runs away into the night, injures herself near the bluffs, and becomes stranded.

When her friends realize she’s missing, they search the island and finally find her injured but alive.

During their rescue, the women begin to confess. Lindsey admits she was with Blake, Zoe’s ex-boyfriend, on the night of Zoe’s disappearance, meaning she had no idea whether Zoe returned home.

Meg confesses that she had been secretly in love with Zoe. Callie insists she never lied but has always feared her family’s involvement.

Their confessions clear away years of suspicion, leaving one mystery unresolved: the photo Lindsey found.

When they examine it closely, they notice the yacht’s upholstery matches that of Callie’s parents’ boat. Confronting her parents in their guesthouse, they demand answers.

Elizabeth, cold and defensive, deflects, while Ben, whose memory has deteriorated, admits he took Zoe out several times to discuss a grant for her jewelry business. His confused recollection—saying she “fell once” and insisting she was “fine”—suggests that Zoe may have accidentally fallen overboard.

Elizabeth erupts, accusing Ben of hiding another affair and selling the boat to cover it up. The friends interpret his babbling as confirmation that Zoe died that day, and that the truth was quietly buried.

Outside, Patricia confronts them again, citing witnesses who saw Ben at the marina and evidence that Lindsey was out with Blake that same night. Callie refuses to engage, declaring that they finally know what happened.

They call the police, who collect the photo and statements, question Ben, and detain him for investigation. The friends stay together through the night, processing the truth they had long avoided.

A final flashback reveals Zoe’s last day. Her business was failing, and she had pinned her hopes on a grant from the Sutter family’s nonprofit.

Ben had recognized her as Callie’s friend and offered to help. On the morning she vanished, she stayed behind after her friends left to meet him one last time on his boat.

She felt uneasy but hopeful that she could secure funding to save her dream. What happened next—whether an accident or something darker—is left unsolved, but for the survivors, understanding how the past destroyed them is its own reckoning.

Through shifting voices and emotional revelations, The Housewarming portrays how trauma ripples across friendships, how truth can be distorted by ambition and guilt, and how closure rarely brings peace.

Characters

Zoe Gilbert

Zoe Gilbert is the missing center around which The Housewarming revolves, both literally and emotionally. She embodies youthful ambition, independence, and charisma—an artist and jeweler whose beauty and charm mask the insecurities beneath her confident exterior.

Through flashbacks and recollections, Zoe emerges as both the sun and shadow of her friend group: magnetic yet manipulative, affectionate yet withholding. Her relationships with the others—particularly Lindsey, Meg, and Callie—are defined by intensity and unspoken competition.

She is a catalyst for their personal evolutions and breakdowns. Her entrepreneurial drive and idealism reflect a need for validation, especially from older, powerful figures like Callie’s father Ben, whose involvement ultimately leads to her disappearance.

Zoe’s story is that of a woman undone by both ambition and misplaced trust, her absence leaving an emotional vacuum that exposes the fragility of those who loved her.

Callie Sutter

Callie Sutter stands as the group’s natural leader and the emotional architect of their reunions. Once confident and charismatic, her poise masks guilt and unresolved trauma tied to Zoe’s disappearance.

Her decision to return to Block Island and host the “housewarming” under the guise of healing is both an act of penance and self-justification. Wealthy and privileged, Callie represents the veneer of success that conceals deep fractures beneath.

Her relationship with her mother, Elizabeth, shapes her emotional restraint and obsession with control. Callie’s public apology and attempt to “reclaim the narrative” about Zoe’s disappearance mirror the same performative tendencies that once destroyed their friendships through her ill-fated television interview.

Yet, her evolution across the story—culminating in confronting her father’s role in Zoe’s death—marks her gradual movement from denial toward truth, even at the cost of dismantling the illusions of her perfect life.

Lindsey

Lindsey is the group’s most volatile and self-destructive member, a woman defined by both envy and loyalty. Her character arc is shaped by her guilt over lying to the police about the night Zoe disappeared and her internal battle between self-preservation and remorse.

She is impulsive, drawn to unhealthy attachments—first to Zoe, then to Fred (later revealed as Cameron Oakes). Lindsey’s life after the disappearance spirals into instability: financial ruin, dependence on men, and addiction.

Yet beneath her recklessness lies an enduring emotional truth—her pain stems not only from Zoe’s loss but from years of feeling overshadowed by her. Her eventual confession and confrontation with her past mark her redemption.

Lindsey represents the psychological cost of secrets—the way guilt festers into paranoia and shame when truth is denied for too long.

Meg Bradley

Meg Bradley, the literary agent among the friends, embodies intellectual restraint and moral conflict. Rational and analytical, she initially seems the most grounded of the group, yet she too is burdened by suppressed emotion—her unspoken love for Zoe.

Meg’s professional involvement in the book about Zoe’s case forces her to relive the past through a lens of commodified tragedy, making her the story’s moral compass and commentator on the ethics of true-crime culture. Her sense of responsibility for Zoe’s memory and her quiet guilt for inaction are counterbalanced by her clarity and strength in uncovering the truth.

Meg is the one who bridges emotion with reason, and her honesty ultimately brings cohesion back to the fractured group. Through her, Kristin Offiler explores the intersection of love, complicity, and the narratives women are forced to live with after trauma.

Tess

Tess is the emotional heart of the story—a woman fragile yet sincere, haunted by maternal guilt and memory. Her postpartum struggles serve as a mirror for her inability to let go of the past and her complex emotional dependency on her old friends.

Tess’s sensitivity makes her both vulnerable and perceptive; she carries the group’s collective grief in a deeply personal way. Her moment of leaving her baby unattended after mistaking a stranger for Zoe captures her psychic unraveling—the line between memory and obsession blurring.

Tess’s eventual confrontation with Patricia and her own complicity reveals her as a tragic but resilient figure who longs for healing. Through Tess, the novel explores how grief transforms into self-punishment and how forgiveness—of oneself and others—becomes the only path to survival.

Patricia Adele

Patricia Adele is the novel’s moral antagonist, a self-fashioned crusader for “truth” whose obsession with Zoe’s case transforms her into a manipulator and profiteer. Initially presented as an amateur blogger driven by empathy, Patricia evolves into a symbol of the exploitative true-crime industry—turning tragedy into entertainment.

Her parasitic fixation on the four friends stems from both curiosity and envy; she becomes a mirror of their guilt, embodying society’s voyeuristic hunger for scandal. Yet, Offiler portrays Patricia with nuance—her loneliness, her craving for relevance, and her belief that she serves justice render her disturbingly human.

Patricia’s confrontation with the women at Callie’s vigil exposes the destructive overlap between moral zeal and ego. She stands not just as a villain, but as a commentary on how truth-seeking can become a form of violence when untethered from compassion.

Nathan Sutter

Nathan, Callie’s husband, functions as a moral contrast to the chaos surrounding the women. Calm, meditative, and emotionally steady, he represents the life Callie has tried to construct in the aftermath of the past—a world of mindfulness and controlled serenity.

However, his presence also underscores Callie’s isolation; his composure often feels detached, his understanding limited to surface empathy. Nathan’s wealth and success, born from their mindfulness app, echo Callie’s attempt to monetize healing just as Patricia monetizes pain.

He is neither villain nor savior but rather a reflection of the hollow peace that material comfort cannot sustain when moral wounds remain unhealed.

Elizabeth and Ben

Elizabeth and Ben Sutter are tragic embodiments of hypocrisy and generational denial. Elizabeth’s social perfectionism and manipulative nature have shaped Callie’s obsession with appearances and control.

She is both protective and cruel, wielding propriety as a weapon. Ben, meanwhile, is the novel’s ultimate revelation—his involvement in Zoe’s death encapsulates the corruption of power, desire, and negligence.

His failing memory becomes both literal and symbolic—a decaying moral consciousness unable to escape the consequences of hidden sins. Together, they illustrate the rot beneath privilege: how wealth and influence can bury the truth but never destroy it.

Fred / Cameron Frederick Oakes

Fred, later revealed as Cameron Frederick Oakes, embodies deception, guilt, and the dangerous magnetism of unresolved grief. His relationship with Lindsey blurs ethical boundaries, built on lies and surveillance.

His past connection with Zoe adds a sinister layer to his character, making him both a red herring and a tragic figure trapped by his own secrets. The photo he possesses—linking Zoe to Ben—serves as the story’s key to unraveling the truth.

Through Fred, the novel examines how obsession with the past can transform into exploitation, and how even those seeking redemption can perpetuate harm.

Themes

Guilt and Accountability

The sense of guilt pervades The Housewarming, shaping every relationship and decision in the story. Each of the four women—Callie, Lindsey, Meg, and Tess—carries her own version of guilt connected to Zoe’s disappearance, but it manifests differently for each of them.

Callie’s guilt stems from her privileged position and the unintended consequences of her televised interview, which deepened suspicion and destroyed her friendships. Lindsey’s guilt is tied to her lies to the police and her lingering jealousy of Zoe, emotions that taint her memories and corrode her self-image.

Meg’s guilt is quieter yet more enduring; her concealed love for Zoe makes her question whether her silence contributed to the tragedy. Tess’s guilt merges with maternal anxiety, revealing how past traumas echo into new stages of life.

Guilt, in the novel, is not only emotional but performative—it dictates how the women present themselves to the world, how they rationalize their actions, and how they repress the truth. Kristin Offiler uses this collective guilt to question whether accountability is ever possible in the aftermath of moral failure.

The women are haunted not just by what happened, but by what they failed to do: to protect, to speak, to trust. Their reunion years later is less about closure than confrontation, where guilt finally meets its reckoning.

The novel suggests that true accountability may never come from police reports or media exposés, but from the private acceptance of one’s own culpability, however unintentional it may have been.

Friendship and Betrayal

The friendship among the four women forms the emotional spine of The Housewarming, yet it is a fragile construct riddled with jealousy, power imbalance, and betrayal. Offiler captures how intimacy among young women often carries unspoken hierarchies—Zoe’s charisma and dominance, Callie’s confidence rooted in privilege, Meg’s quiet emotional depth, Lindsey’s insecurity, and Tess’s dependence on belonging.

The group dynamic, once bonded by shared experiences and laughter, fractures under the strain of tragedy and public scrutiny. What once felt like sisterhood transforms into suspicion and resentment.

The betrayal is not singular; it exists in layers. Callie’s ill-fated interview betrays their collective silence, Lindsey’s deceitful alibi betrays the truth, Meg’s secrecy about her feelings betrays emotional honesty, and Tess’s conversation with Patricia betrays their pact of loyalty.

Through these acts, Offiler portrays friendship not as an unconditional refuge but as a mirror that exposes weakness and fear. Yet, within the same web of betrayal lies yearning—the need to reconnect, to forgive, and to recover something lost.

The housewarming becomes both literal and symbolic: a gathering to reopen a house filled with ghosts, but also a chance to rebuild the burnt-down foundations of trust. The novel ultimately shows that betrayal among friends often comes not from malice but from the desperate human need for self-preservation, and that forgiveness, if it arrives at all, must confront the uncomfortable truth that love and betrayal can coexist.

Media Exploitation and the Ethics of Storytelling

A striking theme in The Housewarming is the exploitation of tragedy by media and the moral decay it exposes. Patricia Adele embodies the hunger for attention disguised as advocacy.

Her transformation from a local blogger to a celebrity podcaster represents how the modern true-crime industry commodifies suffering. By manipulating narratives, editing footage, and rallying online mobs, Patricia blurs the line between journalism and performance.

Offiler’s portrayal of Patricia is not simply villainous but reflective of a collective appetite for scandal; she thrives because the public demands spectacle. Through her, the novel critiques how technology and social media create echo chambers where truth is irrelevant and emotion becomes currency.

The victims of such narratives—Callie and her friends—are stripped of privacy, reduced to characters in someone else’s story. Their identities are rewritten by hashtags and comment threads, leaving them powerless against the public’s need for closure.

Even Callie’s final vigil is tainted by performativity, live-streamed to an audience hungry for revelation rather than reconciliation. Offiler raises uncomfortable questions: who owns a story of pain, and at what point does empathy become exploitation?

In exposing how trauma becomes content, the novel indicts not only Patricia but also society’s voyeuristic fascination with other people’s tragedies, revealing a world where storytelling is less about truth and more about control.

The Burden of Secrets

Secrets form the invisible architecture of The Housewarming, binding and breaking its characters in equal measure. Every relationship in the novel is sustained by what is not said—Zoe’s undisclosed connection to Callie’s father, Meg’s hidden love, Lindsey’s falsified alibi, and Tess’s unspoken doubts.

Secrets in this narrative are both protective and corrosive. Initially, they act as emotional armor, shielding the women from shame, judgment, and each other.

Over time, however, these concealed truths metastasize into guilt and paranoia, distorting memory and identity. Offiler illustrates how secrets isolate individuals within their own narratives, preventing collective healing.

The tension between revelation and concealment drives the story forward: Patricia’s pursuit of “truth” threatens to expose what the women buried, while their fear of exposure reveals the complexity of moral silence. The novel also examines generational secrecy through Callie’s parents—particularly her father’s deceit about his relationship with Zoe, which ultimately unravels the mystery.

The burden of secrets becomes both literal and emotional weight, carried across years until it fractures under the pressure of confrontation. Offiler suggests that truth, when withheld for too long, ceases to protect and instead consumes.

The final scenes, where long-suppressed truths surface, reveal that secrecy can distort even love and grief, leaving behind fragments of honesty that arrive too late to heal but just in time to haunt.

The Intersection of Class, Power, and Privilege

Class and privilege subtly dictate the dynamics of The Housewarming, influencing who is believed, who is blamed, and who gets to move on. Callie’s affluent background shields her from consequences yet isolates her emotionally, while Lindsey, Tess, and Meg, each from less privileged circumstances, suffer the harsher judgment of the public and the law.

Zoe’s ambition as an artist and entrepreneur exposes her vulnerability within these hierarchies—she depends on people like Callie’s father for financial opportunity, a dependence that ultimately leads to her downfall. Offiler uses this imbalance to expose the moral contradictions of privilege: the same structures that offer comfort also perpetuate silence and complicity.

Patricia’s rise as a self-styled crusader for justice mirrors another form of privilege—the digital kind, where influence replaces ethics. The novel portrays how social power, whether through wealth, gender, or media presence, shapes who controls the narrative.

The Gilberts’ grief is filtered through class as well; their daughter’s disappearance becomes a story consumed by those more powerful than them. Through these intersections, Offiler demonstrates that tragedy does not occur in a vacuum—it is filtered through economic and social lenses that determine who is mourned, who is judged, and who is forgotten.

The house Callie buys on Block Island stands as the ultimate metaphor: a luxurious monument built atop unresolved pain, purchased not just with money but with the moral debt of privilege.