The Island of Last Things Summary, Characters and Themes

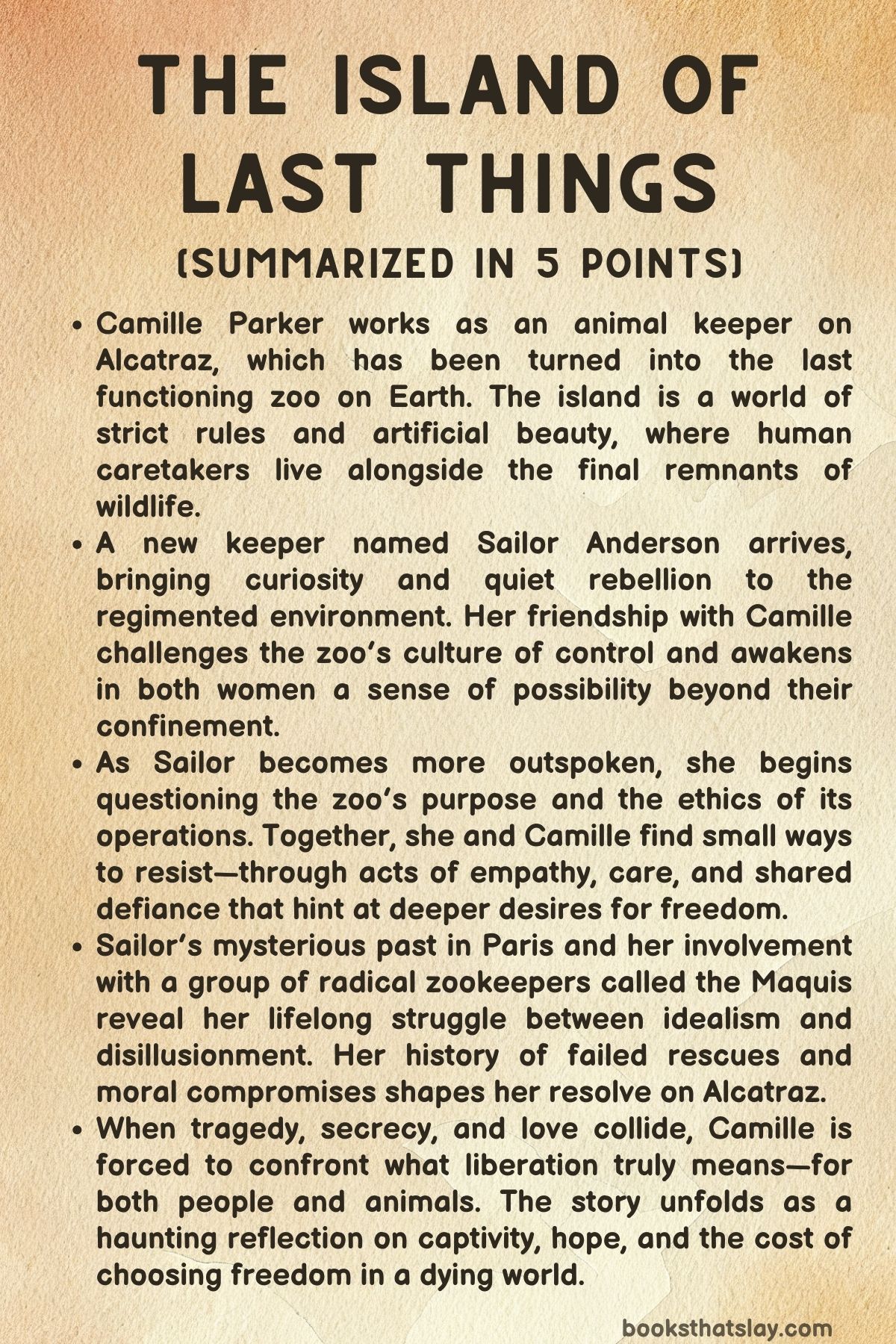

The Island of Last Things by Emma Sloley is a hauntingly imaginative novel set in a near-future world where nature has almost collapsed and human greed has turned survival into spectacle. The story unfolds on Alcatraz Island, repurposed as the last zoo on Earth, owned by the powerful Pinkton family.

Through the eyes of Camille Parker, a quiet zookeeper, readers witness the decaying relationship between humanity and the wild. When Sailor Anderson, a rebellious and mysterious new keeper, arrives, she challenges the oppressive system that cages both animals and people. Their bond, set against a crumbling world, becomes a story of resistance, loss, and rediscovered freedom.

Summary

The narrative begins on Alcatraz Island, now converted into a self-contained zoo where more than two thousand animals and a few hundred keepers live under strict surveillance. Camille Parker, the protagonist, works as an animal keeper for the Pinkton family, who run the institution with military precision.

Her life changes with the arrival of Sailor Anderson, a sharp-witted and fearless new keeper whose curiosity about the zoo’s rules unsettles its sterile order. Camille is assigned to show her around the island, and their initial professional relationship gradually deepens into trust and quiet intimacy.

As they walk through enclosures filled with tigers, jaguars, and primates, Sailor questions the ethics of preserving life through captivity, while Camille, shaped by obedience, defends the system.

During a lavish tour for wealthy patrons, the keepers stage an elaborate show in which guests, after being scrubbed and disinfected, marvel at holographic jungles and endangered animals falsely presented as the last of their kind. The illusion masks a deeper truth: the zoo’s animals are commodities, and the staff are prisoners serving spectacle.

Sailor mocks the performance, but Camille urges caution. Their connection strengthens amid the hypocrisy surrounding them, and a sense of quiet rebellion begins to form.

The novel moves between the present on Alcatraz and fragments of Sailor’s past in Paris, where she once worked at a collapsing zoo during the final days of the natural world. There, environmental disasters and political violence destroyed ecosystems, and a secret group of zookeepers, the Maquis, formed to resist the exploitation of surviving animals.

Sailor’s involvement with them ended in failure and loss, driving her to seek redemption on Alcatraz. Her memories of extinct species and her father’s stories of the Everglades shape her resolve to fight against captivity, even as hope dwindles.

Back on the island, Sailor’s unconventional ideas win her respect and suspicion. She designs new activities to comfort animals and occasionally defies orders.

Camille, drawn to her daring spirit, begins to see the zoo differently—less as a sanctuary and more as a prison for both humans and creatures. When the Paris Zoo officially closes, Alcatraz becomes the last remaining zoo on Earth.

The owner, Mr. Pinkton, declares it a triumph of human ingenuity, though the workers feel it marks the end of the world.

Under his rule, discipline hardens and discontent festers.

Camille and Sailor’s friendship evolves into a quiet partnership marked by late-night walks and shared secrets. Sailor speaks of freedom and rebellion; Camille, cautious yet captivated, follows her lead.

When Sailor starts disappearing on trips to the mainland, Camille grows uneasy. Sailor later reveals she’s in contact with outsiders who might help free the animals.

Despite doubts, Camille cannot resist being drawn into her dream of liberation.

Moments of joy break through their grim lives. Sailor and Camille host a secret Christmas party, filling the island with music and laughter.

The celebration briefly unites the workers but ends with collective punishment when the administrators discover it. Curfews and stricter controls follow, deepening resentment.

Sailor’s defiance only intensifies—she locks a tourist inside a cell for trespassing and confronts guards openly. Camille, both fearful and inspired, senses the boundary between rebellion and ruin narrowing.

As time passes, Sailor grows more secretive. She visits a sick crocodile named Achilles and becomes obsessed with freeing him.

When the animal’s health declines due to artificial food, Sailor intervenes, confronting Joseph, a fellow keeper and her rival, and eventually manipulating events to take over Achilles’s care. Meanwhile, tensions rise with the arrival of new investors and plans to expand the zoo for profit.

Sailor’s faith in the possibility of change collapses as corporate greed tightens its hold.

Outside the island, Sailor meets Johannes, a mainland smuggler posing as an ally of her old resistance group. He tempts her with promises of a “Palace of Exotics,” a grotesque monument where animals would be exhibited for the wealthy elite.

Sailor pretends to cooperate but secretly plans to betray him. When tragedy strikes the zoo—the elephant Kira gives birth to a stillborn calf—the grief unites the staff in despair.

Camille, devastated by the sight of Kira’s mourning, finally commits to Sailor’s plan of escape, believing it their only way out of captivity.

Together, they explore the tunnels beneath Alcatraz and discover a rusted passage leading to the sea. They plan to use it to escape with Achilles.

When they return to execute the plan, a patrol ship forces their waiting boat to flee. Sailor remains undeterred, determined to try again.

Her resolve hardens after learning she is terminally ill with a new strain of Lyme disease. Camille, unaware of the full truth, clings to Sailor’s vision of freedom as a shared destiny.

On the night of the escape, they drug the guards and make their way through the zoo one final time, saying silent goodbyes to the animals. Sailor’s behavior becomes erratic, swinging between affection and fatalism.

When they reach Achilles’s enclosure, Sailor confesses that she loves Camille and suddenly leaps into the water. The crocodile rises and kills her instantly.

Camille collapses, unable to comprehend the horror.

Imprisoned afterward, Camille discovers through Sailor’s belongings that her death was deliberate. Sailor had been coerced by the cartel linked to Johannes but chose to die on her own terms, echoing her parents’ suicide when faced with terminal illness.

Her notes reveal that she intended to deny her captors the satisfaction of exploiting Achilles and that she had left instructions for Camille to continue her mission. She had also arranged contact with an ally named Mr. Li, who could guide Camille to safety.

Upon release, Camille finds herself dismissed from the zoo. Mr. Pinkton admits that her father was killed years earlier resisting the same criminal forces that once targeted Sailor. Carrying Sailor’s belongings and a small bird she secretly hides under her jacket, Camille boards a ferry to the mainland.

As Alcatraz fades into the distance, the bird stirs against her chest—a fragile symbol of the life Sailor tried to protect. Camille feels the faint rhythm of wings and imagines that she and Sailor are finally leaving the island behind, not as keepers or captives, but as survivors moving toward a fragile, uncertain freedom.

Characters

Camille Parker

Camille Parker, the narrator of The Island of Last Things, is a reserved and introspective zookeeper whose life is defined by isolation and routine. Born into modest circumstances as the daughter of a chauffeur to the wealthy Pinkton family, she has grown up surrounded by hierarchies of power and obedience.

Her work on Alcatraz—the world’s last zoo—reflects this ingrained submission to order and control. At the beginning of the story, Camille embodies passivity; she obeys rules, avoids confrontation, and seeks meaning only through her caretaking of animals.

Yet, beneath her compliant exterior lies a yearning for connection and authenticity.

Her growing friendship with Sailor Anderson marks the catalyst for her awakening. Sailor’s rebellious compassion stirs something dormant within her—an ability to question authority and recognize the ethical hypocrisy of the zoo’s “preservation.

” Through their relationship, Camille begins to see the parallels between human captivity and animal confinement, realizing that both she and the creatures she tends are prisoners within a spectacle of control. The tragedy of Sailor’s death profoundly reshapes her.

In the end, Camille transcends her role as a passive observer, choosing to honor Sailor’s defiance by seeking freedom and carrying forward her mission of liberation. Her final act—leaving Alcatraz with a hidden bird—symbolizes her evolution from caged obedience to fragile, determined freedom.

Sailor Anderson

Sailor Anderson is the emotional and moral heart of The Island of Last Things—a complex figure defined by courage, idealism, and tragedy. Introduced as a new zookeeper, she arrives on Alcatraz with a sharp intellect and unflinching skepticism toward authority.

Sailor’s past—rooted in environmental collapse, activism, and her experience with the Maquis resistance in Paris—shapes her into both a revolutionary and a survivor. She is driven by a deep moral conviction that true preservation of life cannot coexist with captivity.

Her compassion for animals transcends professional duty; it becomes a form of resistance against a world that commodifies survival.

Sailor’s rebelliousness manifests through small acts of defiance—freeing birds, questioning the zoo’s bureaucracy, and challenging the moral decay around her. Yet, she is also haunted by personal suffering.

Her terminal illness and history of loss lend her actions a desperate urgency. The revelation that her death was intentional—a conscious surrender to the crocodile Achilles—transforms her from a rebel into a martyr of principle.

Sailor’s love for Camille humanizes her defiance; their bond intertwines tenderness with tragedy. Her death, both shocking and symbolic, becomes a final act of liberation—a refusal to be controlled by disease, corruption, or human cruelty.

Sailor’s legacy lives on through Camille, who becomes the vessel of her hope and rebellion.

Joseph

Joseph, a keeper and distant member of the Pinkton family, serves as a representation of privilege and moral ambiguity within the zoo’s oppressive hierarchy. Confident, pragmatic, and self-assured, he moves easily between the worlds of labor and authority.

His romantic involvement with Camille adds an element of emotional tension to the narrative, especially as Sailor’s influence grows. Joseph’s loyalty lies less with individuals and more with the system that sustains his comfort and identity.

Although he genuinely cares for the animals, Joseph’s understanding of duty is transactional—he maintains order rather than seeking justice. His rivalry with Sailor reveals his insecurity in the face of her conviction.

Their conflict, especially over the welfare of Achilles, exposes his complicity in the zoo’s moral decay. By the novel’s later stages, Joseph becomes both antagonist and victim—a man trapped by the same machinery of control he once defended.

His character underscores the theme that power offers no immunity from confinement; like Camille, he too is imprisoned by the illusion of stability.

Mr. James Pinkton Sr.

Mr. James Pinkton Sr.

, the patriarch and owner of the Alcatraz zoo, embodies the intersection of capitalism, spectacle, and moral corruption that defines The Island of Last Things. He is a modern-day industrial emperor whose wealth allows him to curate the illusion of salvation even as the world collapses around him.

To Pinkton, the zoo is not a sanctuary but a monument to human dominance—a means of immortalizing his legacy under the guise of conservation.

Pinkton’s performative philanthropy is both grotesque and chilling. His speeches frame extinction as triumph, his “charity” gestures conceal exploitation, and his control over the keepers mirrors the imprisonment of the animals.

He symbolizes humanity’s hubris—the belief that ownership can substitute for preservation, and spectacle for empathy. His interaction with Camille near the end, when he reveals her father’s fate, momentarily humanizes him but does not redeem him.

Ultimately, Pinkton represents the corrupted face of progress, a man who mistakes domination for stewardship and profit for immortality.

Feliz

Feliz, the melancholic jaguar, stands as a silent emblem of captivity and despair. His pacing and psychological deterioration—what zookeepers call “zoochosis”—mirror the emotional state of the humans who care for him.

Through Feliz, the narrative draws a powerful parallel between animal suffering and human desolation. He becomes a living metaphor for confinement’s toll, his enclosure a mirror of the island itself.

Sailor’s and Camille’s interactions with Feliz underscore their contrasting philosophies. Where Camille once views his existence as routine responsibility, Sailor recognizes in him a consciousness stifled by imprisonment.

Their empathy toward him—especially Sailor’s insistence that his despair is a form of awareness—transforms him from a background creature into a moral touchstone. Feliz’s presence throughout the story reminds the reader that survival without freedom is not life but endurance, and his tragic stillness reflects the muted cries of an extinguishing world.

Achilles

Achilles, the ancient saltwater crocodile, is both a literal and symbolic presence in The Island of Last Things. He represents nature’s resilience, danger, and the primal truth that life resists human control.

His illness and mistreatment—fed on artificial meat and restrained by technology—embody the grotesque attempt to domesticate the wild. For Sailor, Achilles is more than an animal; he is a kindred spirit, an untamed survivor in a world sterilized by human intervention.

Their connection culminates in Sailor’s death, when she sacrifices herself to him. This act is both horrifying and transcendent.

In being consumed by Achilles, Sailor escapes both disease and captivity, returning herself to the natural order humanity tried to erase. For Camille, Achilles becomes a living shrine to Sailor’s defiance.

His survival after her death symbolizes endurance beyond human interference—a continuity that outlasts civilization’s decay. Achilles thus embodies the story’s central paradox: destruction and liberation entwined, life persisting even through loss.

Birdy

Birdy, another zookeeper and Sailor’s close friend, offers a contrasting emotional perspective to Camille’s narration. Where Camille internalizes her pain and transformation, Birdy experiences hers through social alienation and loyalty.

Her relationship with Sailor is marked by admiration, protectiveness, and confusion. The “tomato” episode and the Christmas party reveal her desire for joy amid repression, but also her growing awareness of the island’s fragility.

Birdy’s evolution parallels Camille’s, though in a quieter key. She learns the cost of rebellion through shared punishment and fear, yet remains steadfast in her affection for Sailor.

Her observations of Sailor’s defiance and her own small acts of complicity make her a subtle but vital witness to the story’s moral awakening. Through Birdy, the novel underscores the idea that resistance can take many forms—sometimes loud and fiery like Sailor’s, and sometimes quiet and enduring like her own.

Themes

Captivity and the Longing for Escape

Life on Alcatraz is bounded by locks, curfews, and observation, and the animals’ cages mirror the keepers’ confined routines. Camille’s work, the randomized rotations, and the constant presence of guards create a behavioral pen where obedience is engineered as carefully as any habitat.

Feliz the jaguar’s restless pacing and “zoochosis” are a visible sign of what the same pressure does to humans: anxiety redirected into ritual, muted rage turned into compliance. Sailor’s rooftop wanderings, the quiet breaches of route and rule, and the tunnel hunt through the old plumbing express a counter-impulse that never leaves the story—the body’s refusal to accept its perimeter.

Even the island’s spectacle of nature, with holograms that simulate open ranges, emphasizes just how little freedom is available. The elephants’ first step outdoors feels momentous because the bar for liberty has fallen so low; a sky-view becomes a revolution.

That longing collects around Achilles, whose brackish pool and degraded diet make him an emblem of power held in place by artificial systems. The planned escape with him is not only a jailbreak for a single animal but a wager that life outside a managed enclosure is still possible.

When Sailor dies in Achilles’s pool, the scene completes a bleak equation: captivity doesn’t only restrict movement; it colonizes imagination, it sets the terms for sacrifice, and it demands a countergesture as grand and terrible as the prison itself. Camille’s final ferry ride with the hidden bird restores a small, stubborn counterweight—flight smuggled past the checkpoint, a heartbeat insisting that the edge of the island is not the edge of hope.

In The Island of Last Things, cages are made of steel and also of policy, spectacle, and fear; escape requires tools and also a story strong enough to outlast the warden’s voice.

Spectacle, Authenticity, and the Commodification of Care

The Alcatraz zoo markets “last of its kind” narratives and choreographs visitor humiliation into the cleaning ritual to sell a premium feeling of access. Butterflies released on cue, holographic rainforests, and a staged intimacy with “Precious” the cat turn conservation into a theater where emotion is the currency and animals are props for catharsis.

The Pinkton operation positions itself as the guardian of life during collapse, yet the work of care is hollowed by branding: the claim of scarcity is inflated, the animals’ biographies are edited, and the keepers’ labor becomes part of an immersive experience for wealthy guests. Sailor’s quick, critical eye exposes these mechanisms, but the spectacle is seductive even to insiders; its dazzle offers order and meaning in a world splintered by environmental grief.

The show does something else too—it monologues over the animals’ reality. Feliz’s despair remains off-script; the elephants’ fear response to a pollinator drone pierces the pageantry only because chaos escapes containment.

Commodification also distorts the keepers’ attachments. Rotations prevent bonds, “productivity” measures flatten relationships, and enrichment becomes stagecraft.

Sailor’s “Bleat-and-Greets” smuggle empathy back into the system by letting animals meet across enclosures, an unsanctioned exchange that refuses the company’s narrative that value flows only to ticket holders. The whole edifice depends on a confusion between seeing and saving, between pathos and practice.

When the Paris Zoo finally closes and Pinkton declares his facility the last refuge, his speech treats catastrophe as brand positioning. The spectacle requires a final act—Titan descending from a helicopter—so the audience can applaud a rescue that never addresses the conditions that made rescue necessary.

The book asks whether a performance of care can meaningfully preserve life, or whether it mostly preserves the feelings of those who can pay to watch.

Power, Capital, and Biopolitical Control

James Pinkton Sr. is not merely a benefactor; he is a sovereign whose gifts—new inhalers, new positions, new zoo acquisitions—arrive with strings that tangle bodies and futures.

Control operates through rules about rotations, through surveillance cameras, through curfews backed by rifle muzzles, and through medical technologies that ration breath in a toxic atmosphere. The keepers’ livelihoods, housing, and identities are bundled with the Pinkton enterprise, so dissent carries the threat of exile, poverty, or targeted violence.

The mainland’s cartels and smugglers, represented by Johannes and his “Palace of Exotics,” offer an alternate regime that is not a moral opposite so much as a market mirror; both treat animals as assets that can be leveraged, displayed, or liquidated. The distinction between philanthropy and extraction blurs when the Pinktons expand daily tours in the same breath that they trumpet conservation.

Biopolitics—authority over who breathes, who eats, who reproduces—extends from people to animals. Kira’s stillbirth is handled inside a framework that manages risk and public narrative, while Achilles’s failing health under a lab-grown diet reveals cost-saving rationales disguised as sustainability.

Admin responses to crisis rely on containment and optics: blame is assigned to Sailor, Camille is quietly dismissed, and the machinery rolls on. Sailor’s ability to negotiate—securing Achilles’s reassignment, tricking a guard, obtaining references through blackmail—shows power’s soft underbelly: it is porous wherever image matters more than truth.

Yet the system absorbs even acts of audacity by converting them into cautionary tales. In this order, freedom is treated as inefficiency, tenderness as a security breach, and mourning as a public-relations hazard.

The Island of Last Things maps how capital claims stewardship over life while concentrating authority, and how those subject to it must choose between complicity, sabotage, or disappearance.

Ethical Rebellion, Complicity, and the Cost of Action

Small disobediences puncture the monotony—sharing a contraband tomato, unlocking a forbidden view of the stars, returning late from the mainland—but each act carries a price, and the group always pays. The Christmas party briefly restores community feeling, only to be followed by financial punishment and renewed intimidation.

Sailor’s resistance style mixes charm, misdirection, and calculated risk. She frees a cedar waxwing, locks an intrusive tourist in a cell, and agitates for the elephants to see daylight.

These are not random flares but a moral grammar: if the system reduces beings to display objects, then acts that restore agency, even for an hour, are not pranks but repairs. Yet rebellion happens inside webs of dependence.

When Sailor manipulates conditions to take over Achilles’s care, she both protects him from negligence and participates in the very hierarchy she opposes. The Maquis backstory deepens the complexity.

Attempts to smuggle animals out of Paris produce one success and one failure, reshaping lives through firings, scattered networks, and criminal threats. The book refuses the comfort of clean hands.

Even Camille’s complicity—blocking a camera so the bird can escape—binds her to consequences she cannot control. The planned extraction of Achilles exposes the tightrope between liberation and trafficking; the same tunnel could lead to sanctuary or to the “Palace of Exotics.

” Sailor’s last act is an argument in blood against instrumentalizing life; by denying the cartel its prize, she transforms her body into a refusal that cannot be repackaged. Afterward, the administration uses her as a scapegoat, proving that power will write the final memo unless another story survives.

Camille’s departure with Sailor’s number for Mr. Li acknowledges that resistance is not a single moment but an itinerary where costs accumulate and the next step is taken anyway.

Extinction, Grief, and the Work of Memory

The world outside the island is hollowed by loss—fungal blights, vanished forests, regulated jellyfish fishing, the rubble of closed zoos—and the story keeps returning to how people carry absence. Sailor’s childhood memories of the Everglades and her father’s manatee jokes glow because they are unrepeatable; the humor is a relic.

Memorials to lost dogs, secret meetings to mourn species, and the keepers’ stunned faces after Kira’s stillbirth locate grief not as a single shock but as a climate. The spectacle tries to manage this grief by giving visitors a scripted weep over “Precious,” by promising that the last zoo secures a legacy, by converting sorrow into a luxury experience.

Real mourning does not submit so easily. Feliz’s pacing, Achilles’s aching jaws, and the elephants’ panic crack the façade and force acknowledgment that extinction is not only a headline but a behavior, a diet, and a body’s failure.

Sailor’s terminal illness scales the theme down to the intimate: the extinction of a person. Her choice to die with the animal she tried to save reframes grief as agency rather than surrender, pulling memory out of the museum and placing it in motion.

Camille’s solitary confinement becomes a chamber of echoes where memory bruises and also preserves. When she finds Sailor’s journals, the pages make a bridge between what happened and what must come next, turning private notes into a guide.

The tiny bird tucked into Camille’s jacket on the ferry is a portable memorial that still breathes, a refusal to let memory stay inert. In The Island of Last Things, remembering is not nostalgia; it is a practice of keeping company with what is gone while making choices that prevent further erasures.

Bodies, Illness, and Autonomy

Power negotiates at the level of bodies: scrubbed visitors staged for humiliation, keepers punished through withheld wages and sleep, and animals sedated, disinfected, or fed synthetics that slowly degrade them. Against this, characters assert autonomy through touch, hunger, and risk.

Camille and Sailor’s handclasp during Titan’s arrival signals a private treaty inside the public spectacle. The tomato shared in secret tastes like the possibility of choosing what enters the body in a place where even air is rationed.

Sailor’s Lyme disease shifts the stakes. Her body becomes a clock that no rule can rewind, and her choices take on a hard clarity: expose the cartel and die hunted, submit to their plan and betray her ethics, or commandeer her end.

Her decision to step from the tower is framed not as despair but as the final reclamation of self from systems that would use her illness to control her actions. Animal bodies show the same argument.

The elephants’ terror at the drone is not symbolism; it is a nervous system responding to a world retooled for machines rather than creatures. Achilles’s improvement after Sailor’s death hints that care aligned with an animal’s nature can still reverse damage, but only if institutions stop treating bodies as line items.

The narrative insists that autonomy is not abstract freedom; it is the concrete right to breathe, to choose food, to move, to mate, to die on one’s own terms. By making illness visible and unavoidable, the book presses a question that outlives the island: who gets to decide what a body is for?

Stories, Sanctuaries, and the Uses of Hope

Every power on the island tells a story. Pinkton tells one about legacy.

The smugglers tell one about grandeur—the “Palace of Exotics. ” The tour script tells one about noble endings and last chances.

Sailor tells a different story: a sanctuary reachable through courage and planning, a place where animals live without handlers and where people remember how to be decent. Whether the sanctuary exists matters less than what the story does.

It organizes risk, recruits allies, and offers a direction for grief that would otherwise pool into paralysis. At the same time, the narrative warns that hope can be counterfeited.

Marketing departments craft sanctuaries that fit into brochures; criminals rebrand cages as palaces. The tension between the sanctuary as a myth and as a map powers Sailor’s choices and tests Camille’s.

After Sailor’s death, the idea does not evaporate. It changes hands.

Sailor’s notes, Mr. Li’s number, and the small bulb from the arboretum become tokens that bind the future to an ethic rather than to a location.

The final image—Camille carrying a live bird across the water—confirms that hope in this world is portable and smuggled, not grand and announced. It lives in minor acts of release, in the refusal to let institutions own the last word about what life requires.

The Island of Last Things suggests that stories are not distractions from survival; they are tools for it. Used wrongly, they anesthetize.

Used well, they guide people out of tunnels, align courage with care, and keep a door open for creatures that still know how to fly.