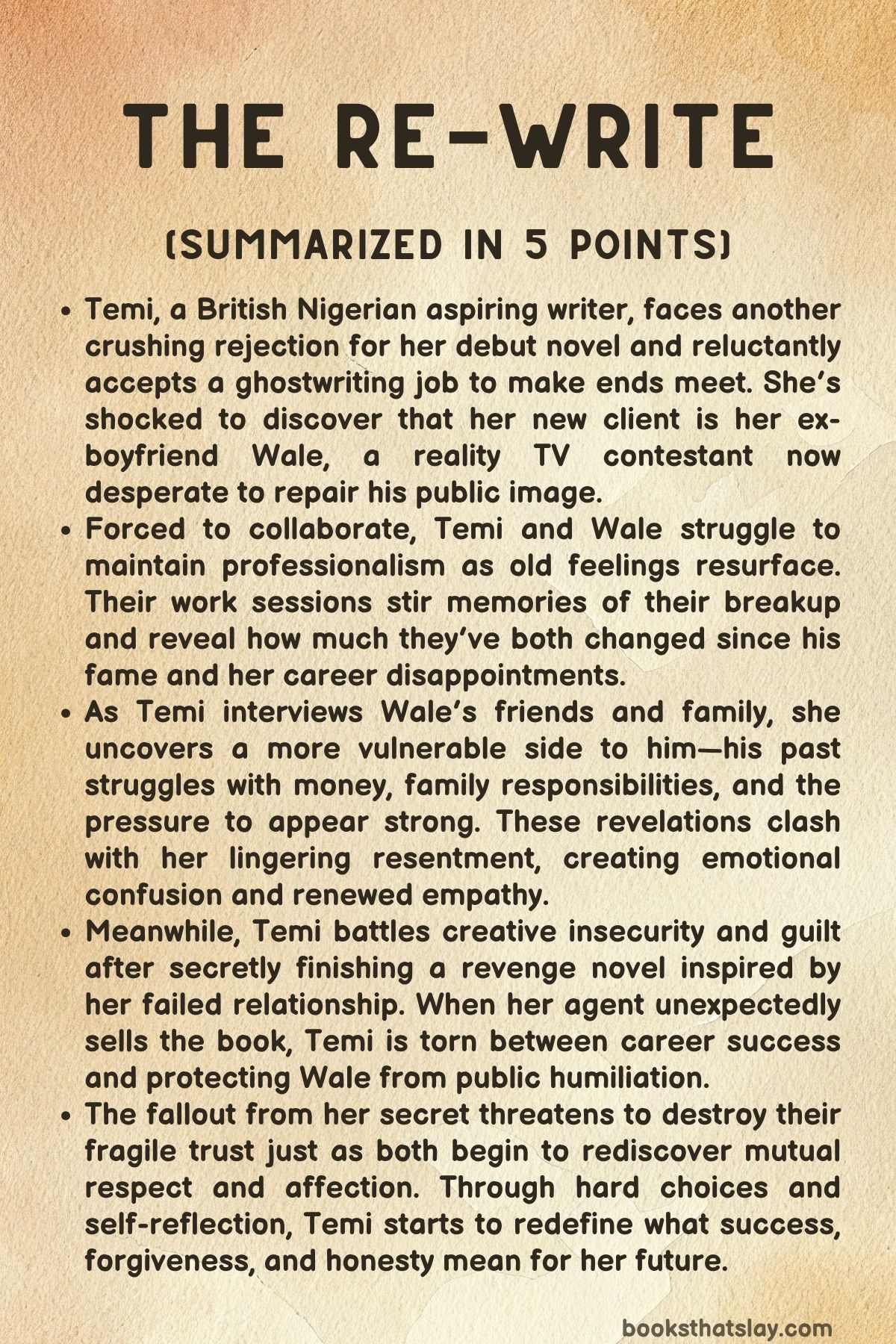

The Re-Write Summary, Characters and Themes

The Re-Write by Lizzie Damilola Blackburn is a contemporary romantic comedy that follows Temi, a young British Nigerian woman struggling to balance her writing ambitions, heartbreak, and self-worth. Once hopeful about publishing her debut novel, Temi’s dreams collapse after a string of rejections.

Life takes an ironic turn when she’s hired to ghostwrite the memoir of her ex-boyfriend, Wale Bandele — a reality TV contestant notorious for his bad-boy image. As they reconnect professionally, old wounds resurface, forcing both to confront past mistakes, hidden insecurities, and the complex intersection of love, ambition, and forgiveness in modern life.

Summary

Temi, a determined aspiring author, watches her ex-boyfriend Wale Bandele appear on a reality dating show called The Villa. Once her charming and passionate partner, Wale is now a minor celebrity notorious for his arrogance and failed on-screen relationships.

Seeing him on television reopens Temi’s emotional scars. When she meets her literary agent, Mayee, later that day, she learns her long-time manuscript, Wildest Dreams, has been rejected again and will no longer be pitched.

Crushed, she faces the collapse of a dream she’s pursued for four years. Mayee pushes her to finish a new romance novel titled Love Drive, but Temi lies that it’s halfway done when she has barely started.

Out of work and emotionally drained, Temi impulsively quits her day job after her boss’s rude call. Shortly after, Mayee offers her a ghostwriting opportunity for a celebrity memoir.

Temi dismisses it until she learns the client is none other than Wale. During the interview, both pretend not to know each other as Wale and his agent, Greg, describe the project — Mister Understood, meant to restore Wale’s reputation.

The tension is palpable, but Temi’s professionalism wins her the job. Despite her reluctance, she accepts, needing the money and unsure if fate is mocking her or offering closure.

When Temi and Wale reunite to work on the memoir, their dynamic is stiff and uncomfortable. Flashbacks reveal how their relationship ended months earlier: after an argument about Wale’s pride and suspicions about Temi’s brief contact with her ex, Seth, their trust unraveled.

Wale’s decision to go ahead with The Villa became the final betrayal. Temi had channeled her heartbreak into a revenge manuscript called The Ultimate Payback, based loosely on Wale.

Working together again forces Temi to confront her unresolved feelings. Interviews with Wale’s loved ones — especially Aunty Shirley and Uncle Les — reveal a different side of him: a shy, kind boy burdened by unspoken family troubles.

Slowly, Temi sees the complexity behind his public image. Their professional interactions soften into warmth, and the old spark returns.

Yet, reminders of the past keep surfacing, especially when Wale’s radio interview credits another ex, Cammie, as his great love. Temi is crushed but continues to focus on writing his story.

Through research, Temi learns that Wale once served as a young carer, looking after a sick relative, which shaped his guarded personality. When she confronts him about it, Wale opens up for the first time about his insecurities, his strained relationship with his ex, and how he often felt inadequate compared to Temi.

Their renewed closeness brings comfort and confusion, and Temi begins to question whether she still loves him.

Meanwhile, Temi’s writing struggles worsen. When her agent demands a draft of Love Drive, she panics, having written almost nothing.

Wale, noticing her stress, brings her food and a new laptop, reminding her of his generosity. Their connection deepens until Temi confides that Kojo, Wale’s friend, once made unwanted advances toward her.

Wale reacts with outrage and finally cuts ties with Kojo. Feeling seen and supported, Temi grows more confident — until she admits to Mayee that she has no Love Drive draft.

Desperate, she sends The Ultimate Payback, her bitter, thinly veiled revenge novel about Wale.

The manuscript receives immediate interest from a new editor, Dionne, who offers a lucrative book deal. But Temi’s triumph turns to dread — the novel portrays Wale harshly, and he still doesn’t know it exists.

Torn between honesty and ambition, Temi hides the truth as their romantic tension grows. When gossip blog The Tea Lounge leaks news of her revenge novel, naming Wale as inspiration, he finds out before she can explain.

Feeling humiliated and betrayed, Wale cuts her off, leaving Temi devastated.

Temi’s parents, learning of the fiasco, comfort her and remind her that failure is not final. Realizing she can’t build success on deceit, Temi withdraws The Ultimate Payback and apologizes publicly to Wale.

Though her publisher retracts the offer, Mayee agrees to represent her again if she commits to honesty. Shona, Temi’s best friend, encourages her to finish Wale’s memoir as an act of integrity.

Determined to make amends, Temi completes the book in a week, pouring empathy and insight into Wale’s life story.

At the charity gala Wale organizes for young carers, Temi attends nervously. She gives him a finished copy of the memoir — a gesture of apology and respect.

Moved, Wale thanks her and invites her to his table. During the event, his heartfelt speech about resilience and community wins over the audience, and he silently acknowledges Temi’s role in helping him rediscover his voice.

Later, chaos erupts when Kojo crashes the afterparty, but Wale handles it calmly, showing his growth and composure. The incident trends online, rehabilitating his image for good.

Afterward, Wale reads the entire memoir overnight and realizes Temi captured his truth with care and depth. He rushes to her flat to reconcile, confessing that he still loves her.

Temi reciprocates, promising openness and trust this time. They plan to rebuild their relationship — Wale focusing on advocacy for carers, and Temi writing a new novel inspired by self-acceptance and redemption.

Seven months later, Temi’s life has turned around. She works successfully as a freelance ghostwriter and has written a new manuscript titled Writing Miss Wrong.

Her former editor, Dionne, expresses interest in publishing it. At Wale’s book launch, now retitled Not Just a Pretty Boy from South, he dedicates it to Temi.

Surrounded by family and friends — including Shona and Fonzo, now a couple — the two celebrate their journey from heartbreak to healing. As they stand together for a group photo, Temi finally feels that both her career and her heart are right where they belong.

Characters

Temi

Temi stands at the heart of The Re-Write as its emotional and moral compass — a young British Nigerian woman navigating the precarious intersection of ambition, love, and self-worth. Her characterization unfolds through layers of vulnerability and determination.

Temi is a dreamer who has poured years into her unpublished manuscript, Wildest Dreams, only to face repeated rejection. Her creative identity is intertwined with a deep need for validation, not only from the publishing world but also from those she loves.

Her impulsive decision to quit her job after one more career setback reveals both her frustration with systemic barriers and her yearning for authenticity. As a Black woman in a largely white publishing landscape, Temi’s struggle to be seen as “marketable” highlights her quiet rebellion against conformity.

Her relationship with Wale reopens old wounds and becomes the mirror through which she confronts her insecurities. Initially bitter and defensive, Temi’s emotions oscillate between resentment and longing, exposing her tendency to guard her heart while secretly craving connection.

Yet, her decision to ghostwrite Wale’s memoir despite their painful past signals a capacity for forgiveness and professionalism that matures throughout the novel. The turning point arrives when she chooses integrity over success, withdrawing her revenge novel The Ultimate Payback even at the cost of her long-awaited book deal.

This act marks her evolution from self-protective fear to emotional honesty. By the end, Temi emerges as a woman who reclaims control of her narrative — no longer defined by rejection, betrayal, or industry expectations, but by her rediscovered sense of purpose and truth.

Wale Bandele

Wale Bandele’s complexity lies in the contradiction between his public persona and his private self. Introduced as the charismatic former contestant of The Villa, he appears confident, charming, and effortlessly likeable — yet beneath the surface resides a deeply insecure man grappling with the weight of societal and personal expectations.

Wale’s upbringing, shaped by financial hardship and the burden of being a young carer, informs both his resilience and emotional restraint. His reluctance to express vulnerability stems from internalized notions of masculinity — the belief that “men can’t show their feelings.

” This guardedness sabotages his relationships, including his romance with Temi, where miscommunication and mistrust eclipse genuine affection.

Through the process of writing his memoir Not Just a Pretty Boy from South, Wale confronts his own contradictions. The act of narrating his life compels him to reckon with his mistakes — his defensiveness, jealousy, and emotional distance.

His reconciliation with Temi is not simply romantic but redemptive, as he learns to accept love without fear and to embrace authenticity over image. His growth culminates during the gala, where he handles public humiliation with composure and channels his fame into advocacy for carers.

Wale’s journey is a quiet transformation from a man defined by ego and performance to one led by empathy and sincerity.

Shona

Shona serves as Temi’s grounding force — a voice of honesty and humor in moments of chaos. She is confident, unapologetic, and fiercely loyal, embodying the type of friend who balances empathy with blunt truth.

Her presence offers emotional relief in the novel’s heavier moments, but more importantly, she acts as Temi’s moral and emotional mirror. Shona’s humor often masks deep perceptiveness; she recognizes Temi’s self-sabotaging tendencies long before Temi does herself.

Her advice — though teasingly delivered — consistently guides Temi toward accountability and self-belief.

Beyond comic relief, Shona represents an alternative model of womanhood in contrast to Temi’s anxiety-ridden perfectionism. She is comfortable in her own skin, bold in her opinions, and ultimately the person who pushes Temi to make amends and finish Wale’s memoir.

By the story’s conclusion, Shona’s partnership with Fonzo reflects the theme of second chances and emotional growth that runs parallel to Temi and Wale’s story, reinforcing the novel’s belief in love’s redemptive possibilities.

Mayee

Mayee embodies the tough-love mentor archetype — a pragmatic literary agent who demands professionalism and results in a world that undervalues emotional labor. At first, she appears as an unsympathetic authority figure, dismissing Temi’s dream project Wildest Dreams for being unmarketable.

Yet her character reveals nuance as the story progresses. Mayee’s sternness stems from an understanding of the harsh realities of publishing, particularly for Black writers who must constantly prove their worth.

Her repeated insistence on deadlines and honesty, though grating to Temi, becomes instrumental in Temi’s eventual moral reckoning.

When Temi confesses the truth about her deceit, Mayee’s response — equal parts reprimand and forgiveness — underscores her investment in Temi’s growth, both as a writer and as a person. Her decision to give Temi another chance reflects professional respect earned, not given.

Mayee’s presence highlights the theme of integrity in creative work and the delicate balance between art, commerce, and authenticity.

Fonzo

Fonzo, Wale’s best friend, offers a lens into Wale’s past and inner life that even Temi cannot access. His loyalty contrasts sharply with Kojo’s toxic influence, positioning him as the embodiment of genuine friendship and emotional steadiness.

Fonzo’s recollections of Wale’s early heartbreaks and vulnerabilities humanize Wale, bridging the gap between the “F-boy” image and the complex man behind it. He becomes a subtle but essential mediator between Wale and Temi, encouraging reconciliation while safeguarding emotional truth.

Fonzo’s budding romance with Shona also mirrors the novel’s broader message — that openness and honesty are prerequisites for love to thrive.

Kojo

Kojo is the narrative’s antagonist, representing performative masculinity and exploitation disguised as friendship. His charisma and influence in Wale’s social circle mask deep insecurity and misogyny.

The revelation that he once assaulted Temi by forcing a kiss exposes his manipulative nature and the toxic culture he perpetuates. Kojo’s eventual downfall, both public and personal, serves as a moral counterpoint to Wale’s redemption.

Where Wale learns to accept responsibility, Kojo remains consumed by pride and resentment. His ejection from the gala scene symbolizes the triumph of accountability and integrity over bravado and deception.

Kathy

Kathy, Wale’s former manager at the charity ACE, plays a pivotal though understated role in uncovering Wale’s humanity. Through her testimony, Temi — and by extension, the reader — discovers the compassionate and self-sacrificing dimension of Wale’s life.

Kathy’s pride in Wale’s contributions and her acknowledgment of his emotional burdens paint a fuller picture of his character. Her eventual recognition at the gala represents the novel’s broader theme of giving due credit to the unseen laborers — carers, mentors, and advocates — whose quiet resilience underpins public success.

Aunty Shirley and Uncle Les

Aunty Shirley and Uncle Les represent warmth, stability, and the power of chosen family. Their influence on Wale is formative, offering him the emotional grounding his biological family often failed to provide.

Through their affection and storytelling, they reveal the tender, introspective side of Wale that fame and heartbreak have obscured. Their acceptance of Temi, even amid past tensions, reflects the novel’s redemptive motif — love and forgiveness as restorative forces.

Their home and presence provide the sense of community that both protagonists, in their ambition and pain, have been missing.

Themes

Identity and Self-Worth

Temi’s journey in The Re-Write explores how personal and professional identity are deeply intertwined, especially for a young woman navigating race, culture, and creative ambition in modern Britain. Her repeated experiences of rejection from publishers erode her confidence, leaving her to question her value as both a writer and a person.

The novel presents her struggle not as a single crisis but as a sustained erosion of self-belief that mirrors the invisibility often experienced by women of color in creative industries. Temi’s identity as a British Nigerian writer becomes central to her sense of worth—her stories are deemed “unmarketable,” a coded dismissal that exposes the publishing industry’s narrow standards of representation.

This theme also unfolds through her interactions with Wale, whose public image and masculinity are defined by stereotypes of Black men as either charming or emotionally detached. Both characters grapple with being misunderstood and commodified in different ways: Temi’s art is judged through a lens of marketability, while Wale’s persona is filtered through the spectacle of reality television.

Their reunion through ghostwriting—where Temi must literally rewrite Wale’s public identity—forces her to confront her own fractured sense of authenticity. The novel shows how self-worth must be reclaimed not through validation from institutions or romantic partners, but through truth-telling and ownership of one’s narrative.

Temi’s decision to reject a lucrative but dishonest book deal marks the moment she redefines herself—not as a rejected writer, but as a creator with moral and artistic integrity.

Ambition and Creative Integrity

Ambition drives every decision Temi makes, but The Re-Write scrutinizes the cost of chasing success in industries that thrive on compromise. Temi’s devotion to her writing career is portrayed with both admiration and critique—her persistence borders on self-destruction as she sacrifices financial stability, relationships, and even her peace of mind to chase publication.

The novel situates ambition not as a noble pursuit but as a complicated form of survival, especially for marginalized artists. Temi’s lie about having written half of Love Drive exposes how ambition can mutate into fear—a fear of failure, of being forgotten, of never being enough.

At the same time, Wale’s ambition to rehabilitate his image after The Villa reveals a parallel anxiety: success that depends on performance rather than authenticity. His willingness to let Temi ghostwrite his memoir highlights how ambition can distort selfhood when it becomes dependent on public approval.

The story critiques how creative industries exploit vulnerability under the guise of opportunity. Yet it also argues that ambition, when reclaimed from fear, becomes transformative.

Temi’s final act of honesty—confessing her deception to her agent and withdrawing The Ultimate Payback—shows that ambition without integrity leads to emptiness. Her eventual recognition as a writer comes not from appeasing others but from creating work that aligns with her truth.

The theme therefore redefines success: it is not the external validation of a book deal, but the internal reconciliation between who she is and what she writes.

Love, Forgiveness, and Emotional Maturity

The romantic arc between Temi and Wale in The Re-Write is not simply a story of rekindled love; it is an examination of what it means to grow emotionally after betrayal and misunderstanding. Their past relationship is marked by insecurity and miscommunication—Wale’s emotional unavailability and Temi’s fear of rejection fracture their bond long before fame intervenes.

The novel refuses to idealize love as redemptive until both characters confront their own emotional immaturity. Wale’s charm and defensiveness conceal years of suppressed pain linked to his family responsibilities and failed relationships, while Temi’s need for control stems from her vulnerability as an artist constantly facing rejection.

When they reunite through the ghostwriting project, their dynamic shifts: the professional setting becomes a crucible for honesty. Love here is not a romantic reward but a space for accountability.

Forgiveness emerges as an act of courage rather than sentimentality—Temi must forgive herself for exploiting their story in her revenge novel just as Wale must forgive her for the betrayal. Their eventual reconciliation at the gala is understated yet powerful, representing emotional evolution rather than mere reconciliation.

The novel suggests that love is sustainable only when grounded in mutual respect, transparency, and emotional literacy. By the end, both characters learn that genuine connection is built not on nostalgia or attraction but on vulnerability and truth.

Representation and Gender Dynamics

The Re-Write engages deeply with the politics of gender and representation, examining how women, particularly Black women, are judged for their ambition and emotional expression. Temi’s creative struggles reveal a systemic bias that devalues stories centered on Black women unless they conform to marketable stereotypes.

Her male counterparts—Wale, Kojo, even her call-center boss—reflect different forms of male entitlement that attempt to undermine her authority, either through dismissal, manipulation, or exploitation. Yet the novel resists portraying Temi as a passive victim.

Her confrontation with Kojo, who once harassed her, and her later decision to report him, showcase the novel’s feminist stance on reclaiming agency. Through Shona’s candid support and Mayee’s tough mentorship, the story highlights the importance of female solidarity within male-dominated spaces.

Even Wale’s transformation challenges toxic masculinity: his acceptance of vulnerability and empathy defies the stereotype of emotional detachment imposed on Black men. The novel thus portrays gender not as a binary of victim and aggressor but as a spectrum of power negotiations.

Temi’s final success, both in her writing and her relationship, underscores that empowerment arises not from external validation but from self-definition. Representation, in this sense, becomes more than visibility—it becomes the right to tell one’s story without apology, compromise, or censorship.

Redemption and the Power of Storytelling

Storytelling in The Re-Write functions as both a weapon and a remedy. Temi’s revenge manuscript, The Ultimate Payback, initially represents her desire to reclaim control after heartbreak, but it also reveals how writing can perpetuate harm when motivated by pain rather than truth.

The public fallout from the book’s leak exposes the ethical weight of storytelling: who has the right to tell which story, and at what cost. Temi’s subsequent redemption—choosing honesty over ambition—shows how storytelling can heal when rooted in empathy.

Parallel to this, Wale’s memoir project reclaims his humanity from media caricature, transforming confession into restoration. The act of writing becomes a bridge between them, enabling both to understand their own pasts and each other.

The theme extends beyond personal redemption to a broader social commentary: the stories that shape public perception often omit the complexity of real lives, especially for people of color in the public eye. By rewriting both her and Wale’s narratives, Temi discovers that truth-telling is an act of liberation.

The closing chapters, where both thrive professionally and emotionally, affirm storytelling as a moral act—one that can either wound or heal depending on intent. Through this, the novel asserts that redemption is not the erasure of past mistakes but the conscious rewriting of one’s life with integrity, compassion, and accountability.