The Secret Book Society Summary, Characters and Themes

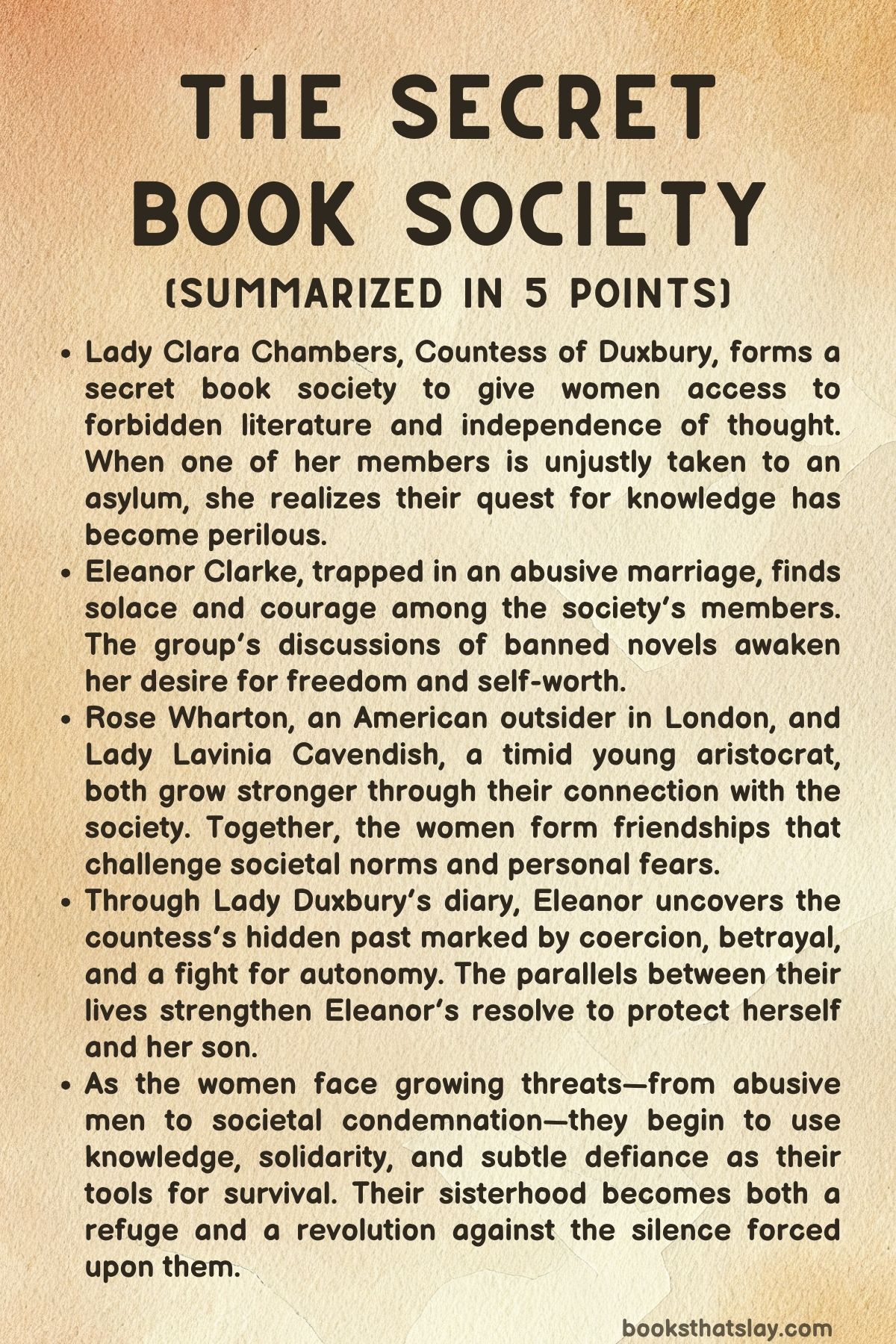

The Secret Book Society by Madeline Martin is a historical novel set in late 19th-century England, where women’s voices and intellects are often dismissed. The story follows Lady Clara Chambers, Countess of Duxbury, and the women she gathers into a secret society dedicated to reading forbidden books and supporting one another against societal oppression.

Through interconnected stories of Lady Duxbury, Eleanor Clarke, Rose Wharton, and Lady Lavinia Cavendish, Martin explores themes of female friendship, courage, and the reclaiming of personal agency. The novel vividly portrays women’s quiet rebellion in an age of rigid gender expectations, showing how shared knowledge becomes an act of survival and empowerment.

Summary

In 1895 London, Lady Clara Chambers, Countess of Duxbury, receives a shocking message from a street boy carrying a single embroidered boot belonging to her friend, Rose Wharton. The boy brings news that Rose has been taken to Leavenhall Lunatic Asylum.

Within the boot, Lady Duxbury finds one of her own letters inviting women to join her secret group, revealing that her discreet charitable society has drawn dangerous attention. When she also receives an ominous bouquet and a threatening note hinting at her past, she realizes someone intends to expose her.

The narrative then moves back two months earlier to Mrs. Eleanor Clarke, a wealthy woman living under the oppressive control of her husband, Cecil.

A secret letter from Lady Duxbury invites Eleanor to join a small society for women interested in reading. Desperate for companionship and mental freedom, she accepts.

Her husband, believing it to be an ordinary tea gathering, allows her to attend.

At the meeting, Eleanor meets Lady Duxbury’s other guests—Mrs. Rose Wharton, an American struggling to fit into English high society, and the timid young Lady Lavinia Cavendish, who is restricted by her family from reading fiction.

The countess welcomes them warmly, revealing her library as a safe haven where women can read banned works and discuss ideas freely. The women are hesitant but begin to bond over shared feelings of isolation and repression.

Lady Lavinia finds unexpected courage from the gathering. At home, she secretly keeps a copy of Jane Eyre that her brother once tried to destroy.

The book, given to her by Lady Duxbury, turns out to have belonged to her late mother, symbolizing her connection to both her family and her suppressed desires for independence. Encouraged by Lady Duxbury and her mother’s subtle support, Lavinia begins to write and express herself more openly.

At a lavish ball hosted by the Clarkes, the women reunite. Eleanor is forced to mask her misery while enduring her husband’s scrutiny.

There she observes Rose’s seemingly glamorous life and Lavinia’s nervous innocence. When Lavinia panics after a dance, Eleanor gently helps her escape the crowd, and their friendship deepens.

The painting they observe—a lonely woman staring at the sea—becomes a silent reflection of their inner longing for freedom.

In their next meeting, the women discuss books that mirror their personal struggles. Rose praises The Female Quixote, Lavinia defends Jane Eyre, and Eleanor speaks passionately of Sense and Sensibility.

As they share their thoughts, their conversations reveal underlying fears: abuse, loneliness, and the risk of madness in a society quick to silence women. Lady Duxbury listens, guiding them with empathy born from her own mysterious pain.

When the others leave, Eleanor remains behind, and Lady Duxbury subtly directs her to a hidden shelf in the library. Inside, Eleanor discovers a diary written by the countess under her previous married names.

The entries unveil the countess’s past: forced into marriage with Viscount Morset after a betrayal, she bore a child conceived in love with a kind bookseller named Elias. Her husband never knew the child was not his.

Enduring humiliation and abuse, she turned to books and herbal remedies as her only solace. The diary ends with her vow to protect her son at any cost.

Through the ongoing meetings, the women’s friendships grow. Rose becomes active in social work for the poor, learning compassion beyond her sheltered life.

Eleanor confesses the truth about her husband’s violence, while Lavinia fears inheriting the madness her family attributes to women who defy them. Lady Duxbury encourages Lavinia to transform her emotions into poetry, turning fear into expression.

Meanwhile, Rose faces her own domestic struggles as her husband’s demeanor grows cold, worsened by his dying brother’s interference.

During a retreat at Lady Duxbury’s estate, Rosewood Cottage, the women are joined by two guests—Mrs. Parish, a spiritual medium, and an outspoken American named Smith, who teaches them self-defense using hatpins.

The countess uses these lessons to empower them, giving each woman a sense of control over her safety. That night, during a séance, they uncover the tragic story of the late Lady Duxbury’s mother-in-law, who took her life after severe postpartum despair.

The revelation resonates with Eleanor, who admits she once felt similar hopelessness after childbirth. The séance brings the women even closer, sharing secrets that had long burdened them.

The following day, Lady Duxbury leads them into her secret garden filled with poisonous and healing plants. She explains their dual nature—how something deadly can also heal.

Quietly, she gives Eleanor access to the garden, signaling an unspoken offer of escape if she ever needs it.

After returning home, Lavinia’s parents discover her journals and decide she must be committed for “hysteria. ” Distraught, Lavinia tries to resist, but her mother eventually persuades her father to reconsider.

Rose, meanwhile, finds courage to tell her husband she is pregnant, only to be threatened by her brother-in-law Byron, who warns that she too could be sent to an asylum. The women’s fears of institutional confinement become horrifyingly real when Eleanor’s husband acts on his cruelty.

Cecil discovers Eleanor’s plans to flee with her son, has her maid beaten, and arranges for her to be committed to Leavenhall Asylum under false pretenses of insanity. As she is dragged away, she manages to slip a message to a bootblack, including one of her rose-embroidered boots, to alert Lady Duxbury.

When Lady Duxbury learns of Eleanor’s confinement, she mobilizes her allies. With the help of solicitor Mr.

Brogan and Lavinia’s fiancé, William Wright, she secures Eleanor’s release after five brutal days. Inside Leavenhall, Eleanor has endured dehumanizing treatment and drug-induced stupor.

Rescued and nursed back to health, she insists on returning home to reclaim her son.

Armed with a vial of belladonna given by Lady Duxbury, Eleanor faces her husband. When he attacks her, fate intervenes—he accidentally poisons himself with a date from a box laced with nightshade, likely prepared earlier by Lady Duxbury.

His death is ruled an accident, freeing Eleanor at last.

Months later, in 1896, peace has returned to the women’s lives. Lavinia is engaged to William and active in the suffrage movement.

Rose has a daughter and continues her charitable work, employing Sam, the boy who once delivered Eleanor’s boot. Eleanor lives quietly with her son, finally safe.

Lady Duxbury, now dedicating her life to protecting women in danger, welcomes new members into the Secret Book Society. The story closes with her assuring a new visitor, Lady Pempton, that it is never too late to seek help—and that knowledge and sisterhood remain the greatest sources of freedom.

Characters

Lady Clara Chambers, Countess of Duxbury

Lady Clara Chambers stands as the commanding heart of The Secret Book Society, a woman who channels her painful past into a mission for liberation and knowledge. Born into privilege but scarred by betrayal and oppression, she becomes a beacon of hope for other women silenced by patriarchy.

Through her transformation from a victimized wife to a mentor and leader, she embodies both resilience and compassion. The novel traces her evolution across years of suffering—forced marriages, lost love, and the cruel constraints of Victorian respectability—yet she emerges as a protector, using intellect and subterfuge to shelter others.

Her secret library and coded gatherings reflect not only rebellion but redemption: each book she lends and each woman she empowers is an act of defiance against the world that once caged her. Beneath her composed exterior, however, remains a sense of guilt and loneliness, particularly surrounding her son’s illegitimacy and the deaths of her husbands.

Still, Lady Duxbury refuses to be consumed by remorse; instead, she repurposes it into purpose, creating a sanctuary where knowledge and friendship replace silence and fear.

Mrs. Eleanor Clarke

Eleanor Clarke’s journey is one of the most harrowing and redemptive in the story. At first, she is the epitome of the oppressed Victorian wife—controlled, isolated, and emotionally brutalized by her husband, Cecil.

Her life is dictated by appearances, her thoughts by fear. Yet through her introduction to Lady Duxbury’s secret society, Eleanor begins to rediscover her own mind and agency.

Books become her doorway to courage; the act of reading transforms from quiet rebellion into survival. The diary of Lady Duxbury becomes her mirror—a testament to shared suffering and endurance—and her eventual liberation is both literal and symbolic.

When she is confined to the asylum, the full extent of her society’s cruelty is revealed, but it is her intellect and will that sustain her. Her final confrontation with Cecil, ending in poetic justice, seals her metamorphosis from victim to survivor.

Eleanor’s strength is not in violence but in quiet determination, maternal love, and moral clarity. By the novel’s end, she reclaims her dignity and becomes a living embodiment of the freedom the Secret Book Society seeks to provide.

Mrs. Rose Wharton

Rose Wharton, the spirited American expatriate, introduces warmth, humor, and cultural contrast to the otherwise rigid English setting of The Secret Book Society. Initially dismissed as frivolous or naïve, she evolves into one of the most compassionate and socially aware members of the group.

Her struggle is both internal and external—alienated from her new home, constrained by her husband and his family, yet yearning for belonging and meaning. Rose’s journey toward empathy and activism, particularly through her work with the Society for the Advancement of the Poor, highlights her moral awakening.

Her pregnancy, initially a point of fear and vulnerability, becomes a catalyst for transformation. Through her friendships with Eleanor and Lavinia, she learns the strength of solidarity among women.

Rose’s American openness challenges English repression, making her a bridge between independence and tradition. In the end, her reconciliation with her husband and her nurturing of the next generation—symbolized by her daughter Clara—reflect hope for renewal and the enduring power of compassion.

Lady Lavinia Cavendish

Lady Lavinia Cavendish is the story’s emblem of youth, sensitivity, and repressed genius. Her character arc captures the emotional and psychological constraints imposed on women deemed “fragile” or “hysterical.” Bullied by her domineering father and haunted by the fate of her institutionalized grandmother, Lavinia’s fear of madness becomes both her cage and her creative fire. Encouraged by Lady Duxbury to write poetry, she transforms her anxiety into art, reclaiming her passion as a strength rather than a flaw.

Her romance with Mr. William Wright introduces the first glimmers of mutual respect and intellectual partnership in her life—a stark contrast to the oppressive male figures around her.

Yet it is not love alone that redeems Lavinia; it is her writing and her courage to confront her father’s tyranny. By the novel’s conclusion, she stands as a figure of emerging womanhood—unbroken, expressive, and determined to live freely.

Lavinia’s growth from timid aristocrat to outspoken writer mirrors the broader awakening of women in the late Victorian era, making her both a personal and symbolic triumph.

Cecil Clarke

Cecil Clarke represents the darkest face of patriarchy within The Secret Book Society. His control over Eleanor is psychological warfare disguised as propriety.

To the world, he is a respectable gentleman; behind closed doors, he is cruel, manipulative, and violent. His obsession with dominance, coupled with his fear of losing social control, drives his abuse.

Cecil’s insistence on committing Eleanor to an asylum when she resists him underscores the Victorian weaponization of mental health institutions against women. Yet his death—swift, ironic, and ambiguously accidental—serves as the story’s moral resolution.

The poisoned date that ends his life is not merely retribution but poetic justice: a symbol of how the tools of control can turn against their wielder. Cecil’s character, while abhorrent, is essential to exposing the societal mechanisms that dehumanize women under the guise of respectability.

Elias and Viscount Morset

These two men, though occupying different stages of Lady Duxbury’s past, are pivotal in shaping her destiny. Elias, the bookseller, embodies forbidden love and intellectual liberation.

His kindness and passion awaken Clara’s heart and mind, offering a glimpse of genuine connection in a world governed by transaction. Yet his disappearance leaves a wound that defines her later mistrust and guardedness.

Viscount Morset, by contrast, personifies the suffocating cruelty of patriarchal marriage. His marriage to Clara is one of dominance and deceit, his abuse so severe that it forces her into moral compromise to protect her son.

The juxtaposition of Elias and Morset illustrates the duality of male influence in the novel—one representing enlightenment, the other oppression—and underscores why Lady Duxbury ultimately builds a world where women need not depend on men for safety or purpose.

Dr. Gimbal and Lady Meddleson

Dr. Gimbal and Lady Meddleson are minor yet critical figures symbolizing societal complicity in women’s oppression.

Dr. Gimbal’s readiness to sign Eleanor’s asylum commitment exposes the moral cowardice of professionals who prioritize propriety over justice.

Though his hesitation hints at remorse, he ultimately surrenders to Cecil’s authority, showing how institutional power crushes individual conscience. Lady Meddleson, on the other hand, wields gossip and blackmail as weapons of control.

Her betrayal of Lady Duxbury’s secrets—first in the past and then in the present—reflects the destructive role of women who internalize patriarchal values and turn them against their own sex. Both characters remind readers that tyranny persists not only through brute force but through social endorsement.

Mr. William Wright

William Wright is the embodiment of a new kind of man in The Secret Book Society—kind, thoughtful, and egalitarian. His gentle defense of Lavinia during social humiliation and his sincere courtship distinguish him from the domineering men that populate the women’s lives.

A solicitor by profession, his respect for justice aligns with the novel’s moral core. By the story’s end, his engagement to Lavinia and his partnership in the suffrage movement signify hope for a generation where love is built on equality rather than power.

William’s presence offers a subtle yet powerful counterpoint to the oppressive masculinity that dominates the novel, reinforcing the theme that liberation must involve both courage and compassion.

Themes

Female Empowerment and Intellectual Freedom

In The Secret Book Society, the pursuit of knowledge becomes a radical act of resistance against the constraints of a patriarchal society. Lady Duxbury’s creation of a secret reading circle for women stands as a symbolic rebellion against a culture that denies them intellectual autonomy.

The act of reading banned literature is not merely about leisure—it represents a reclaiming of voice and identity. Through books, the women learn to articulate desires long suppressed and to question the social hierarchies that bind them.

Eleanor, trapped in an abusive marriage, finds courage through the shared wisdom of literature and the solidarity of her peers. Lavinia’s rediscovery of self-worth through writing, once condemned as hysteria, underscores the liberating power of self-expression.

Lady Duxbury herself embodies the transformation that education brings, having endured personal subjugation yet using her learning to empower others. The novel reveals how literacy and intellectual connection become acts of salvation for women whose world equates silence with virtue.

In this way, Martin portrays knowledge as the ultimate form of emancipation—a force capable of restoring dignity to those long denied it.

Oppression and the Illusion of Respectability

The story exposes the brutal contradictions of Victorian respectability, where social reputation often masks cruelty and control. Beneath the polished veneer of civility lies a system designed to imprison women through decorum and obedience.

Eleanor Clarke’s husband, Cecil, is the embodiment of this hypocrisy—his outward refinement conceals emotional tyranny and physical violence. Rose Wharton’s life, governed by male expectations, illustrates how status becomes another form of bondage.

Even Lavinia’s family wields the threat of insanity as a tool to silence defiance, proving that the asylum is not merely a physical institution but a societal weapon. The novel captures the suffocating pressures women face to conform, behave, and endure, while men are shielded by moral pretense.

Lady Duxbury’s own experiences of abuse behind aristocratic walls further dismantle the illusion of noble virtue. By juxtaposing public propriety with private suffering, Martin paints a portrait of a society obsessed with appearances but devoid of compassion.

Respectability, the book suggests, is a cage forged from lies, where survival often demands deception rather than truth.

Sisterhood and Solidarity

The relationships formed within the Secret Book Society represent more than friendship—they are lifelines in a world intent on isolating women. Each member arrives broken in a different way: Eleanor from abuse, Lavinia from repression, Rose from alienation, and Lady Duxbury from trauma.

Yet together they forge a quiet revolution through empathy and understanding. Their unity transcends class boundaries, challenging the divisions that usually keep women apart.

The gatherings evolve from polite conversation into acts of mutual defense and emotional refuge. When Eleanor is institutionalized, the others risk their reputations to free her, proving that solidarity can dismantle even the most rigid social walls.

The group’s shared reading becomes a metaphor for collective consciousness—each woman interpreting the words differently, yet all arriving at the same recognition of their worth. This solidarity does not erase their pain but transforms it into strength.

In Martin’s world, liberation is not achieved through solitary rebellion but through the courage to stand together, to read, to speak, and to act in defense of one another.

Abuse, Power, and Resistance

At the heart of the novel lies an unflinching portrayal of domestic and institutional abuse. Through Eleanor’s ordeal, The Secret Book Society reveals how power operates through fear and manipulation, often legitimized by medical and legal systems.

The asylum, meant for healing, becomes a mechanism for silencing inconvenient women, echoing the authority of the patriarchal household. Eleanor’s forced confinement mirrors Lady Duxbury’s earlier imprisonment by her husband, linking personal suffering to systemic oppression.

Yet, Martin also charts the emergence of resistance within these confines. The women learn to reclaim agency—whether through self-defense training, coded acts of defiance, or moral courage.

The recurring motif of poison, both literal and symbolic, underscores the tension between destruction and survival. Lady Duxbury’s knowledge of deadly herbs and her willingness to share it signify a turning of power; what once endangered them now becomes protection.

The novel insists that resistance is born not from hatred but from the will to live freely, even if that freedom must be seized in secrecy and risk.

Motherhood and Sacrifice

Motherhood in The Secret Book Society is portrayed as both a blessing and a burden, filled with love yet shadowed by sacrifice. For Lady Duxbury, her son George is the only light in an existence marred by cruelty, but her love becomes the reason for her suffering.

Her diary entries reveal the desperation of a woman forced to protect her child at any cost, even if it means committing morally ambiguous acts. Eleanor’s maternal bond with William mirrors this devotion—her courage to escape her husband stems not from self-preservation alone but from the primal instinct to shield her child.

The narrative also reflects on the societal expectations imposed on mothers, where failure to conform to emotional restraint is labeled hysteria. The séance sequence, exploring the despair of a mother lost to postpartum grief, exposes the silence surrounding women’s mental health.

Through these intertwined portraits, Martin honors maternal love as an act of endurance against oppression. Motherhood, stripped of its sentimental veneer, becomes an arena of resistance where women redefine moral strength through compassion, protection, and unyielding sacrifice.