The Truth Is in the Detours Summary, Characters and Themes

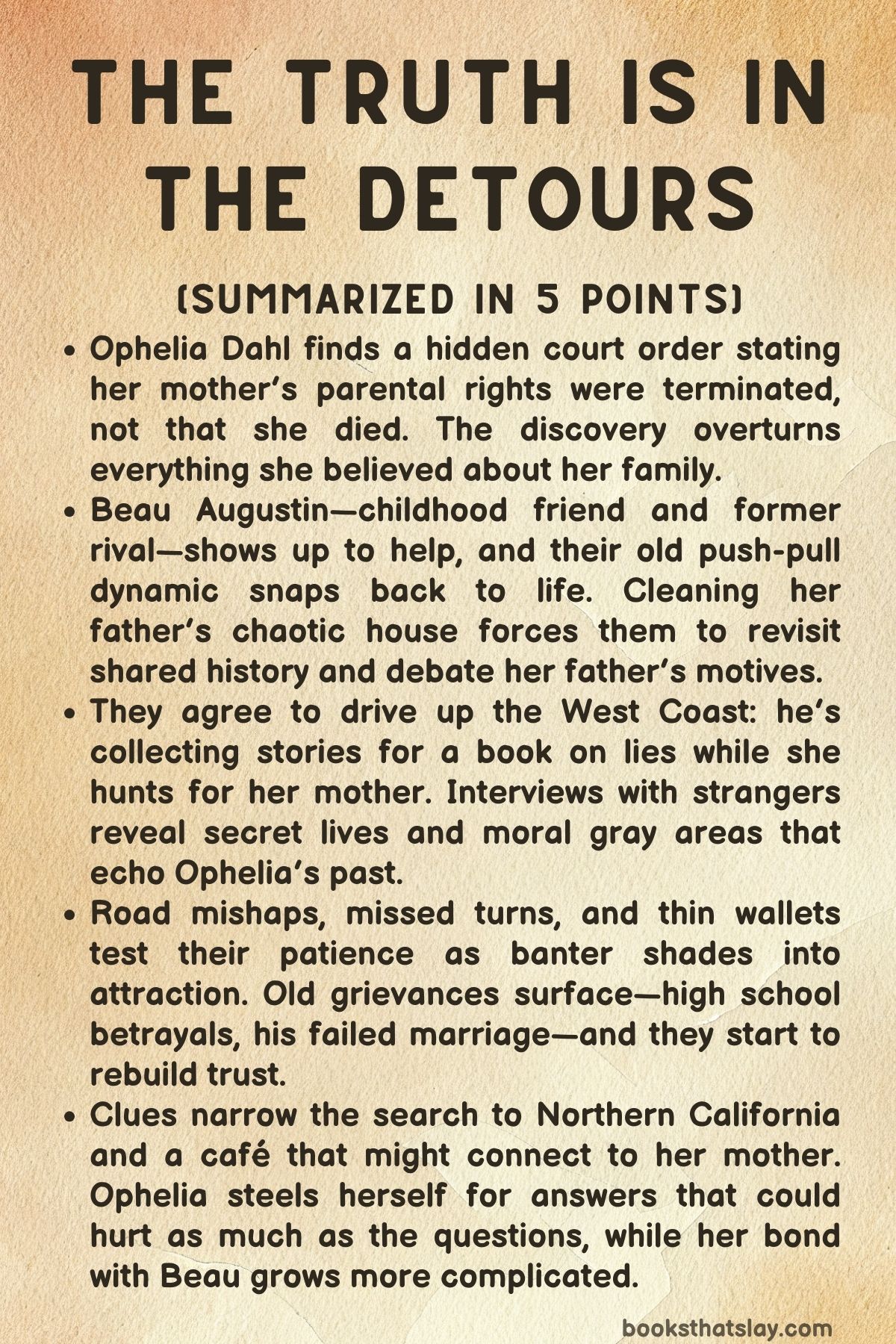

The Truth Is in the Detours by Mara Williams is a contemporary novel about uncovering the hidden layers of truth that lie beneath the stories we tell ourselves. It follows Ophelia Dahl, a woman whose orderly world unravels when she discovers that her mother—believed dead for decades—is actually alive.

This revelation propels her into a journey across the American West alongside Beau Augustin, her childhood friend and intellectual opposite. As they confront old wounds, buried family secrets, and the lies that shaped their lives, Ophelia learns that truth is rarely simple—and that love, forgiveness, and identity are found not in the destination but along the detours.

Summary

Ophelia Dahl’s life takes an unexpected turn after her father’s death when she uncovers a sealed court document among his papers. The document reveals that her mother, Mary Ann Johnson, didn’t die in the car accident her father described years ago but instead lost her parental rights a year later.

The revelation throws Ophelia into turmoil, making her question everything she believed about her parents and her childhood. Amid the emotional chaos of cleaning her father’s house in San Diego, she is visited by Beau Augustin, a childhood friend and former rival who has come at his mother’s urging to check on her.

Their reunion is uneasy—filled with friction, familiarity, and unspoken history.

When Beau discovers the legal document, he’s as shocked as Ophelia. Together, they realize her father concealed a devastating truth: her mother had been alive all along but was legally separated from her.

Confused and hurt, Ophelia feels betrayed by her father’s deceit. Beau argues there might have been a reason behind the lie, but Ophelia rejects his rationalizations, and they part angrily.

Beau’s mother, Lani, soon intervenes, insisting that Beau stay and help Ophelia clean the house. Forced into proximity, the two cautiously begin to cooperate.

As they sift through old belongings, they rekindle fragments of their shared past—memories of friendship, teasing, and adolescent rivalry. A quiet understanding grows between them, though it is laced with irritation and unresolved emotion.

Their fragile truce is interrupted when Ophelia’s friends visit, stirring gossip about Beau’s recent divorce and success as a history professor. Feeling exposed, Ophelia withdraws further into her grief.

Determined to find answers, she searches through her father’s files for more clues about her mother. Beau continues to help her, and their teamwork evolves into companionship marked by lighthearted arguments and occasional tenderness.

He eventually reveals that his current research focuses on lies and deception—families destroyed by hidden truths. Ophelia accuses him of exploiting her story, but he assures her his intention is to help her find her mother.

With his help, she gathers fragments of her mother’s past and learns that Mary might still be alive somewhere in the Pacific Northwest.

Before leaving San Diego, Beau gives Ophelia a folder of potential leads about her mother. Moved by his gesture, Ophelia decides to accompany him on his research trip up the coast, using the journey as an opportunity to search for her mother.

Their road trip begins with playful tension, reminiscent of their youth. Through deserts, diners, and motels, they meet people whose confessions form the backbone of Beau’s research—stories of lies told for love, survival, or shame.

One woman, Natalia, confesses to a decades-old hit-and-run; another man admits to raising a child who wasn’t his. Each story forces Ophelia to question her father’s motives and her own understanding of morality.

These encounters mirror the central question haunting her: can a lie ever be an act of love?

As the miles pass, Ophelia and Beau’s relationship grows more complex. Their banter softens into warmth, but tempers flare when mistakes—like losing Beau’s car keys—escalate into arguments.

A night of frustration and alcohol ends in intimacy, exposing their long-suppressed attraction. Yet their connection is fragile, shadowed by fear and miscommunication.

Ophelia struggles to understand whether Beau’s feelings are genuine or rooted in nostalgia. Their emotional volatility mirrors the unpredictable path of their physical journey, one that is as much about rediscovering trust as it is about uncovering facts.

Their search eventually leads to a small California town where Ophelia discovers that her mother once worked at a café before moving away under a new name. The realization that her mother rebuilt her life without her devastates Ophelia.

Seeking refuge in Beau’s company, she begins to open up about her loneliness and her fractured sense of self. Their attraction reignites at an isolated cabin after a night of vulnerability and closeness.

But the intimacy quickly unravels under the weight of old fears and unspoken doubts. Both are haunted by past betrayals—Beau by his failed marriage and Ophelia by her father’s deception.

Their fragile bond fractures again when Beau’s estranged wife, Bianca, reappears, forcing Ophelia to question his honesty. Feeling manipulated, she returns home to San Diego, determined to face her past alone.

There, she encounters her mother, Mary, who has come to explain everything. Mary reveals a history of untreated bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis that made her dangerous to herself and to Ophelia.

Following several hospitalizations and a near-fatal incident, Mary agreed with Henry, Ophelia’s father, to legally end her parental rights so their daughter could grow up safely. Henry maintained the lie of Mary’s death to shield Ophelia from pain.

Though devastated, Ophelia finally understands the motives behind her parents’ choices: their deception, however cruel, was rooted in love and protection.

After the confrontation, Ophelia begins to rebuild her life. She sells her father’s house, adopts a rescue dog, and redirects her business toward food services, finding peace in the act of creating and nourishing.

She continues therapy and cautiously resumes contact with her mother through shared work in the café kitchen—a space where words give way to mutual understanding. Meanwhile, Beau’s career flourishes as he publishes his book, The Truths We Tell Ourselves, dedicated to Ophelia and exploring the role of lies in shaping identity and relationships.

Despite their separation, he continues to reach out to her through messages that blend apology, affection, and hope.

On their shared birthday, Ophelia decides to take control of her life once again. Driving north with her dog, she surprises Beau at his home, where he is celebrating quietly.

She brings a carrot cake, a gesture of reconciliation, and admits her fear of being hurt but chooses to trust him. Beau, in turn, confesses that he has loved her since childhood and that their connection was never about pity or obligation.

They reconcile with a kiss, symbolizing not a perfect ending but an honest new beginning.

Two years later, the pair have built a life together in Northern California. Ophelia’s catering and cooking business is thriving, and she continues to repair her bond with her mother through shared meals and quiet companionship.

Beau’s book has gained attention, though he insists that its real success lies in helping people confront their own truths. During a visit to his parents’ home in San Diego, Beau leads Ophelia to the backyard where they once played as children.

Beneath twinkling lights and the old tree house that witnessed their first “marriage,” he proposes. Ophelia says yes, affirming her belief that truth, however painful, leads to healing—and that the detours of life, once seen as missteps, were the path all along.

Characters

Ophelia Dahl

Ophelia is the emotional core of The Truth Is in the Detours, introduced in raw grief and thrown into an identity crisis by a court order that contradicts the family myth of her mother’s death. Her arc tracks the move from wounded daughter to self-determining adult: she begins guarded and reactive, clinging to certainties about her father’s virtue and her mother’s absence, and gradually learns to hold contradictory truths without collapsing.

The road trip exposes her to mosaics of deceit that refract her own life, and each interview chips at her black-and-white thinking until she can admit complexity in love, loyalty, and survival. Professionally scattered yet deeply capable, she is at once chaotic and nurturing, a woman who cooks to create safety and who uses pragmatism as armor.

The romance with Beau evolves from sparring to intimacy precisely because she learns to speak plainly about fear, abandonment, and desire. When she finally meets Mary and later chooses measured reconnection, Ophelia practices a hard, adult mercy: she neither excuses harm nor lets it define her future.

By the end, her choices—to rebuild her business around food, to adopt Adonis, to return on their shared birthday, to accept Beau’s proposal—signal agency, not rescue.

Beauregard “Beau” Augustin

Beau is a study in control, intellect, and the costs of emotional misreading. A precise historian writing on deception, he initially treats truth as an archival problem to be solved, not a living wound to be tended.

His brusqueness, rules, and competence camouflage tenderness, loyalty, and a protective streak that has long been focused on Ophelia. The failed marriage to Bianca and the secretiveness around his separation expose his blind spot: he curates facts to avoid messy confrontation.

On the road, his interviews become mirrors he cannot dodge, forcing him to admit that love requires presence rather than interpretation. The keychain and lost wedding ring episode punctures his façade, revealing grief, ambivalence, and a boy who once waited on a porch with a corsage.

His best qualities—steadiness, accountability, an ethic of care—emerge when he admits fault, apologizes without performance, and chooses Ophelia in public and private. The proposal under the childhood tree house completes his movement from historian of lies to practitioner of transparent devotion.

Mary Ann Johnson

Mary is the ghost who becomes a person, complicated by illness, stigma, and love expressed through absence. The revelation that her parental rights were terminated reframes her not as a deserter but as someone swallowed by untreated bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis, whose actions endangered the child she adored.

Her most radical act is consent: pushing for termination to secure Ophelia’s safety and colluding in the fiction of her own death so the girl could grow without disruption. Years later she builds an ordinary life and a café, a domestic rhythm that testifies to recovery and a yearning for steadiness.

When she finally faces Ophelia, she brings accountability rather than demands, offering a way forward grounded in work, recipes, and time. Mary’s character argues that protection can wound and that healing requires both boundaries and invitation.

Henry Dahl

Henry is remembered through objects, voicemail, and the architecture of a lie told in love. He is the parent who stayed, the keeper of the home and the story, and the narrative reveals the burden of a caretaker navigating courts, hospitals, and a child’s longing.

His deception protected Ophelia’s sense of safety but also planted the seeds of her later rupture; he chooses silence to spare her and bears the moral cost himself. The guava cake, the cluttered house, the careful concealments sketch a man who managed crises with competence and tenderness yet never found a vocabulary for fear.

In death he becomes the unsolved question that propels Ophelia’s growth, a reminder that even loving choices can create future reckonings.

Lani Augustin

Lani embodies practical compassion. She arrives with food, boundaries, and humor, orchestrating care without condescension and insisting that grief be fed and floors be swept.

As a maternal counterpoint to Mary’s absence, Lani models sustaining love that is neither sentimental nor invasive. Her presence softens Beau’s rigidity and gives Ophelia a stable family table to sit at while her own history destabilizes.

She quietly midwives the renewal between the two protagonists, making hospitality itself a form of wisdom.

Bianca

Bianca functions as a catalyst exposing Beau’s contradictions. Her deceptions and the trailing negotiation over their separation highlight how easily intellect can rationalize avoidance.

She is not a caricatured villain; rather, she marks the cost of relationships built on curated impressions. Bianca’s reappearance forces Beau to choose candor over triangulation and clarifies for Ophelia that love must be chosen in daylight.

Cherry and Simone

Cherry and Simone represent the pull of surface belonging and the abrasions of friendship formed around distraction rather than depth. Their gossip, invitations, and boundary crossings—especially Cherry’s decision to involve a toxic ex—pressure Ophelia’s old reflex to seek approval.

The eventual breach helps Ophelia prune her social world, making space for relationships aligned with honesty and care.

Carlos and Serena

Carlos and Serena offer a hospitable mirror in which Beau and Ophelia can see themselves without old scripts. Their home is a neutral ground where reconciliation becomes possible, and Carlos’s gentle revelations about Beau’s college devotion recontextualize years of misread signals.

They demonstrate how community can midwife repair by witnessing without meddling.

Natalia Bridgewater

Natalia’s confession of a fatal hit-and-run is the road book’s first moral provocation. She frames a life defined by secret restitution rather than public accountability, provoking debate about whether sustained penance can stand in for confession.

For Ophelia, Natalia embodies the ache of irreparable harm and the possibility that love for the living can coexist with unforgiven pasts. For Beau, she is a case study that starts to leak into his own life.

Jeremiah Abernathy

Jeremiah’s lifelong lie—raising a son not biologically his—asks whether truth is genetic or enacted. His impending exposure by modern testing modernizes the novel’s concern with how technology outpaces human readiness for truth.

He refracts Henry’s and Mary’s choices, suggesting that parenthood is a daily practice that can be both generous and ethically fraught when built atop silence.

Anna Thorne

Anna’s betrayal of a friend over an invention is ambition stripped of loyalty. She introduces class and entitlement into the ethics-of-deceit tapestry, showing how success narratives can launder theft.

For Ophelia, Anna crystallizes a nascent ethic: talent without conscience corrodes intimacy and self-respect.

Abilene

Abilene’s story of a hidden pregnancy and a daughter raised as a sister is the novel’s most piercing parallel to Ophelia’s origins. Her banishment by religious respectability exposes how communities weaponize shame, and her lingering not-knowing maps the psychic cost of erasure.

She forces Ophelia to confront the distinction between being harmed by a lie and surviving because of one.

Jack

Jack, Mary’s husband and co-owner of the café, is sketched as the steward of Mary’s second life. His presence signals that Mary achieved stability and partnership, complicating any easy narrative of permanent brokenness.

Jack’s ordinary kindness—embedded in a workplace and marriage—helps make reconciliation imaginable for Ophelia by proving Mary could love safely again.

Ronald and Juniper

Ronald, the realtor, and Juniper, the demanding client, externalize pressure points that test Ophelia’s resilience and boundaries. Ronald’s inspection calls and the jeopardized sale ground her grief in adult logistics, while Juniper’s exploitative expectations spotlight the costs of people-pleasing.

Together they push Ophelia toward firmer self-advocacy and a reoriented career.

Adonis

Adonis, the scruffy dog, is more than a mascot; he is a tactile commitment to care outside crisis. His adoption marks a hinge from survival to stewardship, anchoring Ophelia’s new routines and symbolizing a home life chosen rather than inherited.

Themes

Truth, Secrecy, and the Ethics of Protection

Truth arrives like a disruptive guest in The Truth Is in the Detours, not as a clean ledger entry but as a messy stack of documents, contradictory memories, and motives that refuse simple moral sorting. The novel stages a continual argument about whether secrecy can ever be an act of love.

Henry’s decision to fabricate Mary’s death, the court’s termination order hidden in a drawer, and Mary’s later agreement to preserve the lie together form a protective shell that keeps Ophelia physically safe but emotionally orphaned. Through Beau’s interviews—Natalia’s fatal hit-and-run, Jeremiah’s hidden paternity, Anna’s stolen idea, Abilene’s erased motherhood—the book builds a comparative case file showing that concealment may halt immediate harm while sowing a longer trauma that blooms years later.

Ophelia’s reactions move through anger, yearning, and a pragmatic hunger for facts, modeling a process in which truth is less an endpoint than a practice: searching records, asking better questions, tolerating ambiguity when answers are incomplete. The narrative refuses a neat verdict because motives crosscut outcomes; some lies shield children from immediate danger, some mask selfish gains, and some begin as care but calcify into control.

The central ethical tension is not simply “lying versus telling the truth,” but whether adults can accept the cost of truth for themselves rather than outsourcing that cost to a child who must carry it for decades. In the end, the book suggests that protection without transparency is time-limited; what is withheld will demand interest, and payment arrives in the currency of disorientation, mistrust, and a fractured sense of self.

Ophelia’s eventual choice to face the full record—keeping the document long enough to understand it, then discarding it after integration—shows how truth can become restorative only when someone is ready to carry it and permitted to reinterpret what protection should mean.

Grief as Reorientation, Not Just Loss

Grief in the novel starts with death but quickly exposes lost versions of the living. When Ophelia cleans her father’s house, she isn’t only sifting through objects; she is testing the reliability of her origin story.

The ache of Henry’s absence makes room for questions she never had permission to ask, and each cupboard forces a recalibration: who was my father if he could stage a maternal death certificate through silence; who am I if the scar on my body marks a different history than I was told? The book pays close attention to the bodily rhythms of grief—missed meals, insomnia, the way ordinary tasks like sorting mail or making coffee become acts of survival.

Lani’s insistence on food and rest becomes a counter-ritual, suggesting that mourning is communal management of the body so the mind can attempt difficult thinking. On the road, grief widens; roadside motels, wildfire smoke, stalled cell service, and dead car batteries mirror the internal outages that accompany bereavement.

Even Ophelia’s professional unraveling—client meltdowns, bank penalties, the threatened house sale—functions as an externalization of how loss disorganizes judgment and capacity. Yet the narrative steers grief toward reorientation.

Ophelia learns that missing her father and revising her opinion of him can coexist; love is not erased by accountability. She eventually adopts Adonis, returns to therapy, and reshapes her business, demonstrating that mourning can become an architecture for new habits.

The proposal scene does not cancel sorrow but reframes it: the memory of Henry is invited to the ceremony through the backyard setting and family presence. Grief here is less a wound that closes than a compass reset, pointing the character toward a future that honors the dead by insisting on fuller truths among the living.

Identity, Narrative, and the Right to Self-Authorship

Ophelia’s quest is not only genealogical; it is editorial. She recognizes that the story she has told herself—mother dead, father heroic, childhood fixed—is a draft written by other hands.

The discovery of the court order introduces competing plotlines, and her road trip doubles as a revision workshop on identity. Each interview Beau conducts offers a model of narrative self-management: Natalia funds a hidden restitution story; Jeremiah parents across a biological discontinuity; Abilene lives with an erased maternity that still shapes her.

Ophelia observes how people curate facts to survive, then decides which curations she will keep. The book also treats names and professions as narrative tools.

Ophelia shifts from concierge tasks toward food, a move that reconnects her to sensory grounding, community, and the café labor that eventually eases conversations with Mary. Mary herself has changed cities, hair color, and workplaces, adopting a marriage and a business that create a new public self while leaving private debts outstanding.

When Ophelia confronts the café reality—recognition not granted, a name on a credit card serving as the trigger—the scene dramatizes how identity requires validation by others to become legible. Later, Ophelia refuses to let either Henry’s deception or Mary’s illness dictate the final genre of her life; she rejects tragedy as the only option and writes toward reconciliation without surrendering discernment.

The act of discarding the Oregon file after confirming its contents is emblematic: she will be informed by the archive, not imprisoned by it. By the epilogue, identities are still porous—media misreads Beau’s book; family history remains complicated—but Ophelia stands as the authorized biographer of herself.

The text argues that self-authorship is achieved when a person accepts conflicting chapters, preserves the evidence, and chooses the tone of the next page.

Friendship, Desire, and the Long Arc of Attachment

The relationship between Ophelia and Beau is built from shared childhood, rivalry, hurt, and dormant longing that mutates under pressure. Their banter, petty judgments, and periodic cruelties reveal how intimacy can calcify into roles—his rigidity performing safety, her chaos performing independence—until crisis demands an update.

The road trip supplies proximity and repetition: cheap motels, fast food lines, cabins without Wi-Fi, and co-authored errands strip away performative distance. Physical gestures—Beau’s quiet food offerings, Ophelia’s scalp massage, accidental hallway collisions—operate as subtext for feelings neither is ready to state plainly.

The first sexual encounter is not a neat pivot to romance; it is followed by panic, withdrawal, and miscommunication, showing how desire can magnify unresolved grievances instead of curing them. Crucially, the novel refuses the fantasy that love simply replaces older attachments; Beau’s marriage and the ghost of Bianca interfere at the worst moment, and Ophelia’s fear of being a placeholder collides with his fear of being abandoned again.

Reconciliation requires narrative repair rather than chemistry: apologies reference specific injuries (prom night, social betrayals, academic comparisons), and future promises are anchored in daily competencies—who drives, who cooks, who handles logistics. By the closing proposal, the relationship is not idealized; it is chosen.

The backyard tree house functions as a continuity object connecting child play to adult commitment, suggesting that long arcs of attachment demand stewardship of shared memory along with present tenderness. The book ultimately frames romantic love as a practice of re-writing: you cannot edit the past facts, but you can change the margins where trust, humor, and rituals of care are inscribed.

Mental Illness, Responsibility, and the Limits of Blame

Mary’s undiagnosed bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis complicate any simple indictment. The crash that scarred Ophelia, the abduction from preschool, and the courtroom termination are presented not as excuses but as context that shifts how responsibility is assigned.

The novel is careful with cause and effect: the state intervenes because risk is real; Henry colludes in a deception because stability for a child appears to require a narrative severance; Mary eventually advocates for her own erasure to prevent further damage. Yet the ethical residue remains: thirty years later, a grown woman must rebuild her inner map.

The story challenges readers to hold two truths: illness can impair consent, and consequences still land on the innocent. Importantly, recovery is shown as labor over time—treatment, funded care, and a measured return to relational life through work at Café Huckleberry.

Mary’s apology is neither melodramatic nor self-exculpating; she names the harm, offers documentation, and asks only for the possibility of future knowing. The book suggests that accountability in the context of illness is relational rather than punitive.

It lives in the quality of ongoing contact: cooking alongside one another, tolerating awkward silences, and allowing affection to accumulate again in small, non-catastrophic moments. The legal document is a relic of the state’s blunt instrument; the café kitchen is a model of distributed responsibility where knives, heat, and timing require cooperation.

By placing Ophelia’s healing in culinary practice—measured, sensory, repeatable—the novel proposes that when blame reaches its explanatory limit, shared work can carry what words cannot, creating a scaffold for trust that does not deny history.

Work, Competence, and the Economics of Stability

Professional life is not side décor in the novel; it is a pressure system that shapes character decisions. Ophelia’s concierge business exposes her to clients whose demands mirror the book’s theme of control—Juniper’s fixation on a sculpture becomes a proxy for how wealthy patrons outsource anxiety.

The overdraft spiral, the reordering of transactions, and the house inspection crises are precise depictions of how financial precarity compounds emotional strain. These setbacks are not punishment for poor choices; they dramatize how systems—bank policies, real estate due diligence, digital connectivity—can tilt a life off balance.

Against that backdrop, the shift toward food services is both practical and symbolic. Cooking creates immediate value, invites repeatable routines, and anchors Ophelia in a community of eaters rather than a hierarchy of patrons.

Beau’s academic work, meanwhile, presents a different economy: prestige, book tours, media narratives that sensationalize the wrong elements. His research agenda on deceit is both intellectual and personal remediation, and the West Coast interviews double as a paid structure for his own meaning-making.

The couple’s eventual domestic workspace—new house, coexisting careers—illustrates a model of partnership where competence is admired rather than resented. The ring lost with the keys and the later proposal retie material symbols to labor: ordinary diligence (keeping track of objects, maintaining vehicles, making meals) underwrites the grand gestures.

The story argues that love requires logistics, and stability is built from the unglamorous work of budgets, calendars, and shared kitchens. By showing Ophelia’s business flourishing precisely when her personal boundaries and routines strengthen, the book links economic agency to narrative authority: money stress no longer scripts the plot; it becomes one subplot among many, managed rather than managing.

Road Narratives, Detours, and the Practice of Choice

The title signals the structural principle: fate is not a straight highway, and the information that matters most often appears when routes close and plans fail. Wildfire smoke, dead batteries, lost keys, closed highways, and bad motels are not random obstacles; they are pedagogical events that force characters to reveal priorities under constraint.

Detours also function ethically: the stops for interviews become mirrors held up to Ophelia’s situation, each story of deception offering a possible interpretation for her parents’ actions. The book reframes delay as diagnostic—time off the planned route reveals who carries snacks, who makes the call, who remembers to rest, who insists on the hot tub even when air quality is poor.

The characters learn to read one another’s competencies and vulnerabilities under the minor emergencies that travel guarantees. Choice is the practice honed by these detours.

Ophelia chooses to ride along rather than wait at home; she chooses not to meet Mary with witnesses; she chooses to pause the relationship after Oakland rather than cling through confusion; she chooses later to drive north with Adonis on their shared birthday. Each selection is an authorship act, refusing the passivity that secrets once imposed.

The final return to the childhood backyard does not negate the philosophy; it confirms it. The route home is itself a detour turned destination, the place where pretend vows from the past are re-chosen as adult commitments.

By the end, the narrative proposes that a good life is not the absence of misdirection but the accumulation of wise reroutings. Detours reveal character, and character, exercised repeatedly on back roads and during breakdowns, becomes destiny.

Forgiveness, Reconciliation, and Choosing a Future

Forgiveness in the novel is a staged process rather than a theatrical absolution. Ophelia withholds it when Mary first explains, not out of pettiness but because comprehension cannot be rushed.

Forgiveness is shown as the art of temporal pacing: you cannot resolve thirty years of absence in one porch conversation. The reconciliation with Beau follows a similar rhythm; attraction cannot shortcut trust, and apologies must attach to verifiable change—honest disclosure about Bianca, a willingness to be chosen openly, and proof that he values Ophelia outside of crisis.

The birthday sequence, with the list of thirty-five truths, marks a maturity pivot: confession framed as specificity, not grand declarations. Importantly, the book allows reconciliation without erasure.

Ophelia keeps portions of herself unassimilated—business goals, therapy, boundaries around contact with Mary—so that love does not require self-abandonment. When the proposal arrives under fairy lights by the old tree house, the yes is an informed consent grounded in shared history and present competence.

Mary’s arc follows the same logic; early meetings in the café kitchen become the safe container where talk can happen while dough rises and frosting sets, allowing relationship to grow at a pace calibrated to reality. The novel’s closing mood is therefore not triumph but orientation: everyone understands more, everyone carries scars, and everyone commits to practices that can hold the weight of what has happened.

Forgiveness becomes a daily craft—meals made, chapters written, dogs walked, appointments kept—through which the future is not guaranteed but continuously chosen.