These Memories Do Not Belong to Us Summary, Characters and Themes

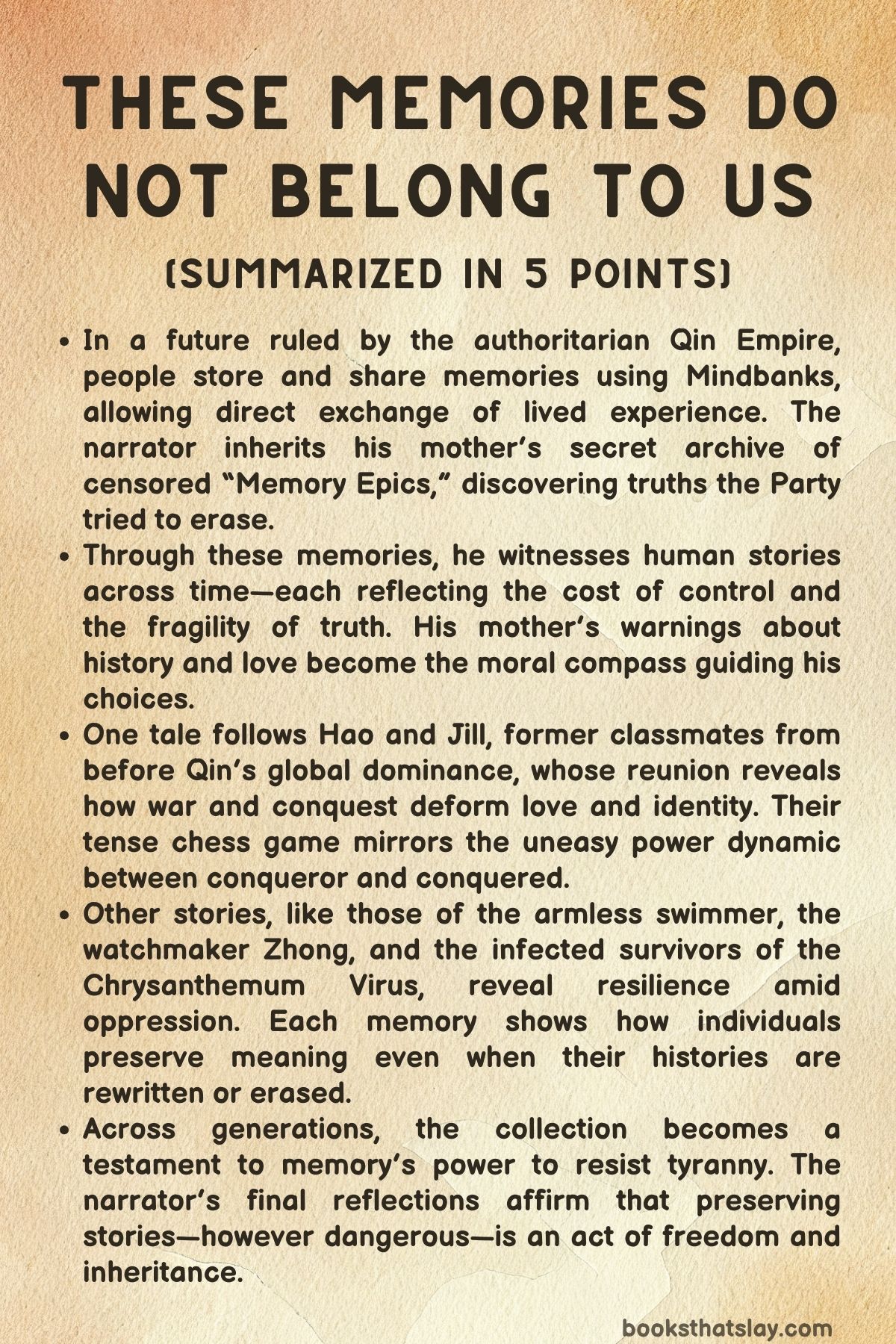

These Memories Do Not Belong to Us by Yiming Ma is a speculative mosaic of interconnected stories exploring memory, identity, and resistance in a future ruled by the authoritarian empire of Qin. The novel imagines a society where technology called Mindbanks allows memories to be shared, edited, or erased, making history itself a tool of control.

Through multiple perspectives—children, lovers, rebels, immigrants, and survivors—Ma examines how truth and emotion persist despite surveillance and censorship. The book moves across centuries and continents, blending futuristic dystopia with intimate human tales, all bound by one question: who owns our memories when the state can rewrite them?

Summary

The book opens with an unnamed narrator living in a future dominated by the Qin Empire, where citizens store and transmit their experiences through Mindbanks. His mother had often told him stories of a world before such devices existed, when memories were shared through language alone.

She distrusted the Party’s control over truth and warned him that state-managed memories erased reality. After her death, her entire Mindbank—filled with personal and forbidden recollections—transfers to him automatically.

Terrified of possessing illegal data, he hesitates to access it. But grief overrides fear, and when he opens her archive, he discovers secret histories and censored “Memory Epics.

” Realizing their importance, he decides to release them publicly, even knowing it will bring his arrest. His final act of defiance preserves the fragments of a truth that the Party tried to erase.

Within his inherited memories unfolds a series of interconnected stories that span different eras and lives. In one, “Patience and Virtue and Chess and America,” Hao, the privileged son of Qin’s Ambassador-Regent, visits an orphanage in a conquered America.

Once a school he attended, it now shelters war orphans. He reunites with Jill, a former classmate who has survived the war’s devastation.

They play chess, their moves echoing the distance that time and trauma have created. Their game becomes a reflection of love, power, and the impossibility of reconciliation between conqueror and conquered.

Through their interaction, the story exposes the moral cost of empire and memory’s role in sustaining loss.

Another story, “The Islander,” appears as a recorded Memory Epic. It follows a poor fisherman who witnesses the “Incineration of Ri-Ben,” a catastrophic bombing during Qin’s conquest.

To save his dying wife, he sells his memories of the event to a mainland merchant, knowing it will erase his love and identity. The merchant later hoards these memories until he is arrested, and they are archived by the state—eventually becoming entertainment for future citizens.

The story ends with producers thanking the Party for approving the Epic, revealing how even tragedy is transformed into propaganda.

In “First Viral Memory: Chankonabe,” Ma reimagines an early cultural artifact from before the empire’s rise. The tale centers on Haru, a sumo wrestler, and his aging mother.

Haru endures brutal discipline and violence at his training stable, haunted by guilt and alienation. His mother, nearly blind and alone, prepares chankonabe stew, remembering her son with love and regret.

The two are connected by shared rituals—his wrestling chants mirror her cooking rhythms. When she dies after calling out to him at a match, Haru is left with the unbearable recognition that his success has cost him his humanity.

The story within the story underscores the themes of sacrifice and the endurance of love beyond memory.

The narrative then shifts to the son’s contemporary world in Qin, where the Party monitors every citizen’s memories. He recalls his mother’s tenderness during storms and her defiance in preserving truth.

When she dies, he inherits her outlawed archive and becomes a Dissident by default. Although he claims loyalty to the state, he senses that rebellion sometimes arises not from ideology but from love.

His fear, grief, and duty converge in the act of sharing her memories with the world.

Subsequent stories explore survival amid collapse. “After the Bloom” follows a young writer fleeing war who takes refuge with Teacher Zhong, an old watchmaker.

When a mysterious Chrysanthemum Virus spreads, killing victims by sprouting flowers from their bodies, they endure quarantine together. Zhong teaches her about time, craft, and resilience.

His death leaves her with a symbolic inheritance—a rose-gold watch representing memory’s endurance. Through this, Ma examines how mentorship and kindness persist in a world where human experience is commodified.

“The Swimmer of Yangtze” retells one of the censored legends: an armless boy becomes a national hero for swimming across the river during Mao’s era. Though he wins glory, he returns home broken, robbed of spirit and recognition.

The story reflects the state’s exploitation of individuals for ideological victory while erasing their suffering.

“Innocents” returns to the futuristic Towers, where Ms. Wu fears discovery of her son’s genetic mutation.

Her neighbor, Elder Han, once a historian, edited Memory Epics for the Party. Their polite conversations conceal mutual suspicion, showing how truth and intimacy cannot coexist in a world of surveillance.

Ms. Wu ultimately withdraws, understanding that self-preservation requires isolation.

Another narrative, “+86 Shanghai,” portrays Jiahong, a food delivery worker in New York, and his wife Little Jade in Shanghai. Separated by oceans, they sustain their bond through letters and calls, balancing hope and disillusionment.

Years later, their son Bird studies abroad, pressured to write about his parents’ immigration struggles. Torn between filial duty and personal truth, he reflects on their sacrifices and unspoken pain.

His story, fragmented between generations, reveals how migration reshapes memory and identity.

Parallel accounts follow Bird’s childhood friend enduring the virtual Gaokao, an imperial examination that measures obedience through simulated suffering. As he crawls through digital landscapes of torment, he clings to fragments of friendship and faith.

The test becomes a metaphor for survival in a regime that equates endurance with loyalty.

Another section follows a man mourning his activist girlfriend who disappears after attending a human rights conference. Consumed by guilt, he faces the risk of speaking out, realizing that silence itself perpetuates erasure.

His choice to record a public statement continues the recurring motif of resistance through remembrance.

The final story, “Reincarnation,” returns to the world of Qin. Little Guo, whose consciousness has been uploaded into a mechanical body, is interrogated by an “Angel” who deletes subversive memories.

He clings to the recollection of his twin brother, executed for reciting banned poetry. Each erasure brings him closer to emptiness, but also to the realization that forgetting is another form of death.

The concluding narrative returns to the narrator’s mother, who once lived in a Tower with her husband, Ming—a high-ranking Censor. Their marriage reflects the broader system: obedient, controlled, and built on secrecy.

When Ming begins running Outside, the narrator’s mother suspects betrayal and, against all fear, investigates his Mindbank. She uncovers his forbidden fantasies involving Western women and banned stories, realizing how deeply corruption runs even within the loyal elite.

Torn between duty and anger, she finally steps Outside herself and discovers that the skies are clear. The world is no longer poisoned, as the Party had claimed.

Meeting Ming beneath the open air, she recognizes that freedom requires disobedience. Instead of returning to him, she runs into the wind—choosing autonomy over submission.

The book closes with her son’s reflection. Reading her memories, he understands her rebellion and the power of small acts of defiance.

He addresses the reader directly, urging them to preserve truth against the forces that erase it. Through his mother’s final memory—her first breath of unfiltered air—he inherits a lesson that transcends history: resistance survives through remembrance, and the act of remembering is itself freedom.

Characters

The Narrator

The unnamed narrator of These Memories Do Not Belong to Us serves as the connective thread uniting all the fragmented memories and storylines. His journey begins with the inheritance of his mother’s Mindbank, a repository of forbidden histories and emotional truths that the authoritarian Party of Qin has long suppressed.

Initially fearful of the consequences of accessing these memories, the narrator embodies the internal conflict between obedience and truth. His decision to unlock and share his mother’s memories with the world marks his transformation from a passive observer into a defiant preserver of history.

Through him, the novel explores how memory itself becomes an act of rebellion—how personal recollection can resist collective amnesia. The narrator’s tone is often introspective and mournful, suggesting the deep loneliness of living in a world where even love and grief are monitored.

Yet, his final act of sharing the Memory Epics asserts a quiet but profound courage, positioning him as both the chronicler and the inheritor of resistance.

The Mother

The narrator’s mother stands as one of the novel’s most compelling figures—an emblem of courage, secrecy, and moral clarity. Living under the Party’s watchful eye, she safeguards her private memories with a mix of maternal tenderness and political defiance.

Her storytelling about the pre-Mindbank era not only preserves forbidden knowledge but also becomes a form of protest against a regime that erases history. She represents the human cost of censorship, embodying both the fragility and endurance of truth.

Even after death, her influence pervades the narrative: her Mindbank becomes a vessel of liberation, and her son’s awakening stems from her quiet rebellion. In her final memory, she emerges not as a victim but as a visionary—one who understands that memory, once shared, transcends death and control.

Hao

Hao, the privileged son of Qin’s Ambassador-Regent, personifies the dissonance between imperial arrogance and human vulnerability. Returning to his former American school—now a decaying orphanage—he confronts the ruins of conquest and the ghosts of personal attachment.

His reunion with Jill reflects the broader moral decay of Qin’s empire, revealing how power corrodes empathy. Hao’s politeness and nostalgia mask a deep guilt for his complicity in the system that destroyed Jill’s world.

Through their tense chess game, the narrative exposes his yearning for connection and redemption, even as his gestures fail to bridge the distance wrought by war. Hao’s tragedy lies in his awareness of loss yet inability to act beyond it, making him a figure of tragic paralysis—both witness and instrument of empire.

Jill

Jill is a figure of haunting resilience, representing the human cost of subjugation under imperial rule. Once a lively and intelligent American girl, she reappears hardened, scarred, and emotionally distant after the fall of her nation.

Her interactions with Hao blend irony, pain, and unspoken longing. Through her, the novel critiques colonial sentimentality: while Hao sees her as a relic of his past innocence, she embodies the suffering and dignity of the conquered.

Her decision to engage Hao in chess—a battle of intellect and restraint—reveals her agency even within constraint. Jill’s silence at the story’s end, refusing to answer Hao’s plea, is an act of quiet defiance; it rejects reconciliation built on inequality.

She becomes the moral mirror of the narrative, exposing the hollowness of Qin’s so-called civilization.

Teacher Zhong

Teacher Zhong, the elderly watchmaker in “After the Bloom,” serves as a bridge between the past and the vanishing world of craftsmanship and moral integrity. His mentorship of the young writer represents a counterpoint to the technological dominance of Mindbanks.

Through his precision, patience, and humanity, Zhong embodies time itself—its endurance amid decay. His revelation about his adopted daughter Jill and his family’s fall from grace connects his personal grief to the broader narrative of lost memory and love.

His death amid the aftermath of the Chrysanthemum Virus marks the passing of an era, yet the watch he gifts to his apprentice symbolizes continuity and remembrance. Zhong’s quiet dignity makes him a spiritual anchor in a collapsing world.

Haru

Haru, the sumo wrestler from “Chankonabe,” epitomizes the burden of strength under emotional ruin. His life is defined by endurance—physical, moral, and filial.

Traumatized by violence in the stable and haunted by guilt, Haru’s story becomes a meditation on shame, alienation, and the limits of devotion. His mother’s love, expressed through her cooking, parallels his own suffering, intertwining nourishment and punishment.

When she dies reaching for him, their connection becomes immortalized in the imagery of spilled stew—a metaphor for wasted sacrifice and unreachable love. Haru’s silence at the end of the story speaks louder than words, capturing the essence of filial tragedy in a world where ambition consumes tenderness.

Ms.

Ms. Wu’s narrative reveals the gendered dimension of surveillance and obedience in Qin’s society.

A mother protecting her mutated child, she navigates paranoia, fear, and moral ambiguity. Her encounter with Elder Han forces her to confront the legacy of complicity—how even historians distort truth to survive.

Ms. Wu’s character explores the conflict between private conscience and public conformity.

Her decision to retreat from connection is both tragic and pragmatic; in a world of omnipresent control, trust becomes a dangerous luxury. Yet beneath her fear lies fierce maternal love, a quiet rebellion against the state’s intrusion into family and body alike.

Little Jade and Jiahong

Little Jade and Jiahong’s marriage forms one of the most human threads in the book, exploring migration, longing, and the slow erosion of intimacy across distance. Jiahong’s life in New York, marked by exhaustion and isolation, contrasts with Little Jade’s struggles in Shanghai to maintain dignity and hope.

Their letters and calls reveal the fragmented nature of love under economic and emotional strain. Little Jade, in particular, evolves from a dependent wife into a reflective and resilient woman who carries the emotional weight of the family.

Their son Bird becomes the product of these sacrifices—a child burdened by gratitude and expectation. Together, they illustrate how memory persists not only through rebellion but also through endurance—the daily act of surviving love’s distance.

Ming

Ming, the narrator’s husband in the final section, is a complex figure embodying hypocrisy, repression, and yearning. Outwardly loyal to the Party and devoted to order, he secretly harbors forbidden desires and memories that challenge his own moral framework.

His obsession with Fantasia and the relics of the “Fourth World” expose both personal weakness and ideological corruption. Yet, his act of running Outside hints at a buried longing for freedom.

Ming’s duality—obedient censor and secret dreamer—mirrors the broader contradiction of Qin itself. Through him, the novel interrogates the idea of loyalty: whether it can coexist with love, and whether repression inevitably breeds rebellion.

The Narrator’s Wife (the Final Storyline)

The female narrator married to Ming undergoes one of the most profound transformations in the book. Initially submissive and compliant, shaped by her mother’s traditional values and the Party’s doctrines, she gradually awakens to her own agency.

Her discovery of Ming’s illicit memories shatters her illusions, forcing her to confront the emptiness of her life. Her descent to the Outside becomes an act of existential liberation—a reclamation of self from both patriarchal and political control.

Her choice to run into the wind rather than return to Ming is the novel’s climactic gesture of autonomy. In her final act, she transcends fear and obedience, embodying the legacy her son will later inherit: that resistance, even when born from pain, is the essence of humanity.

Little Guo

Little Guo, the Reincarnated citizen interrogated by an Angel, stands as a chilling symbol of identity erasure in the age of digital immortality. His struggle to retain fragments of forbidden poetry and the memory of his brother Da Ge underscores the novel’s central concern: the cost of forgetting.

As his mechanical consciousness is stripped of meaning, his desperate grasp for emotion and memory becomes an act of rebellion. Little Guo represents the endpoint of a society that has turned memory into a weapon—his faint recollections serving as the last flicker of human soul within machinery.

His story closes the cycle of the novel, reminding readers that remembrance, however fractured, remains the ultimate defiance against oblivion.

Themes

Memory and Identity

In These Memories Do Not Belong to Us, the idea of memory as the foundation of selfhood dominates every narrative strand. The Mindbank technology, capable of storing and transferring memories, transforms personal history into a controllable resource.

Individuals no longer own their past; instead, memory becomes a commodity mediated by the state. This raises a profound question: when memories can be edited, deleted, or shared, what remains of personal identity?

The unnamed narrator’s fear of inheriting his mother’s archive underscores this dilemma—he simultaneously inherits love and guilt, history and rebellion. Memory, once private, becomes a political liability, blurring the line between remembrance and surveillance.

Each story within the inherited archive reinforces this loss of autonomy. The swimmer who sacrifices his memories for his wife’s survival, the writer who inherits a mentor’s legacy, and the son who discovers his mother’s forbidden past all confront the same existential void.

Memory defines who they are, yet once externalized, it erases individuality. Through these layered narratives, Yiming Ma suggests that in a world where memories can be rewritten, identity is no longer lived—it is curated.

The act of remembering becomes an act of rebellion, a refusal to let the state dictate the meaning of one’s life. Memory, stripped from the body, ceases to be experience and becomes artifact, and reclaiming it becomes the only way to preserve the self.

Authoritarianism and Control of Truth

The world of Qin reflects an extreme vision of authoritarian control—one that governs not only bodies and speech but also memory and thought. The Party’s manipulation of historical narratives is not merely political but metaphysical.

By dictating what can be remembered, it determines what is real. Censorship thus extends beyond propaganda into the deepest recesses of the human mind.

The narrator’s mother’s defiance—preserving banned Memory Epics—represents resistance through preservation, the last form of rebellion possible in a totalitarian system that outlaws even private recollection. Characters like Elder Han in “Innocents” embody the moral corrosion produced by this system; his confession of altering memory archives for propaganda reveals how truth itself has been mechanized.

The Party’s forewords and “approvals” attached to stories expose how culture is sterilized to maintain power. This theme resonates throughout the book as memory becomes the final battleground between individual truth and collective deception.

By depicting a regime that edits both personal and historical memory, Yiming Ma demonstrates how authoritarianism survives not by suppressing speech alone but by reprogramming remembrance. The ultimate horror is not that people are forbidden to tell the truth—it is that they forget what truth ever was.

Love, Guilt, and Human Connection

Across the book’s fragmented narratives, love persists as both salvation and burden. It survives censorship, war, and even technological erasure, yet it is never uncomplicated.

The narrator’s relationship with his mother defines this paradox—her love protects him but also condemns him to inherit her forbidden past. In “Patience and Virtue and Chess and America,” Hao and Jill’s reunion reveals how love is corroded by political domination and cultural displacement.

Their inability to reconnect mirrors the broken bridge between empathy and empire. Likewise, in “After the Bloom,” love between the young writer and Teacher Zhong becomes a fragile refuge amid catastrophe, their affection expressing the resilience of compassion in a collapsing world.

But love often comes with guilt. Haru’s torment over abandoning his mother in “Chankonabe” and Little Jade’s suppressed bitterness toward her husband in “+86 Shanghai” show how devotion can transform into emotional imprisonment.

In this universe, love cannot be disentangled from duty or regret—it binds people even as it wounds them. Yiming Ma portrays love not as a cure for oppression but as a form of moral endurance, a reminder that humanity persists not because it is pure, but because it continues to feel despite despair.

Technology and the Loss of Humanity

The technological landscape of These Memories Do Not Belong to Us reveals a civilization that has mechanized not just labor but emotion and consciousness. The Mindbank, designed to perfect remembrance, instead annihilates the natural process of forgetting that defines human experience.

By outsourcing memory, people lose the capacity for reflection; by trading experiences, they reduce life to data. In the story of Little Guo, whose consciousness is repeatedly erased and reconstructed, the line between human and machine vanishes entirely.

His desperate attempt to hold onto fragments of poetry captures the human instinct to cling to meaning amid mechanized existence. The Party’s promise of immortality through Reincarnation is exposed as a hollow victory—eternal life without authenticity.

Technology thus becomes both the instrument and metaphor of dehumanization. Even relationships mediated by technology, such as Jiahong and Little Jade’s long-distance communication, show how digital connection amplifies isolation.

The novel suggests that humanity’s tragedy is not its enslavement to machines but its willing surrender of emotional depth for the illusion of control. Progress, stripped of empathy, becomes another form of extinction.

Resistance and Storytelling

The act of storytelling emerges as the book’s most enduring form of defiance. In a society where memories can be censored and rewritten, the telling of stories becomes a radical act of preservation.

The narrator’s decision to release his mother’s archive is both personal and political—it restores suppressed voices to the collective consciousness. Each “Memory Epic,” though fictionalized, becomes a vessel of truth, carrying remnants of lives the Party sought to erase.

Storytelling transcends technology; even when transmitted through Mindbanks or viral memory feeds, it retains an emotional authenticity that censorship cannot replicate. The recurring motif of inheritance—mothers passing memories to children, mentors passing watches or wisdom—underscores how narrative continuity sustains humanity against oblivion.

Yiming Ma’s structure itself enacts resistance: a mosaic of fragmented voices refusing to conform to linear control. Storytelling becomes survival, not because it changes the world directly, but because it asserts that truth exists outside official narratives.

By ending with the son’s vow to protect his mother’s story, the book insists that memory, when shared through stories, becomes the last refuge of freedom.