Too Old For This Summary, Characters and Themes

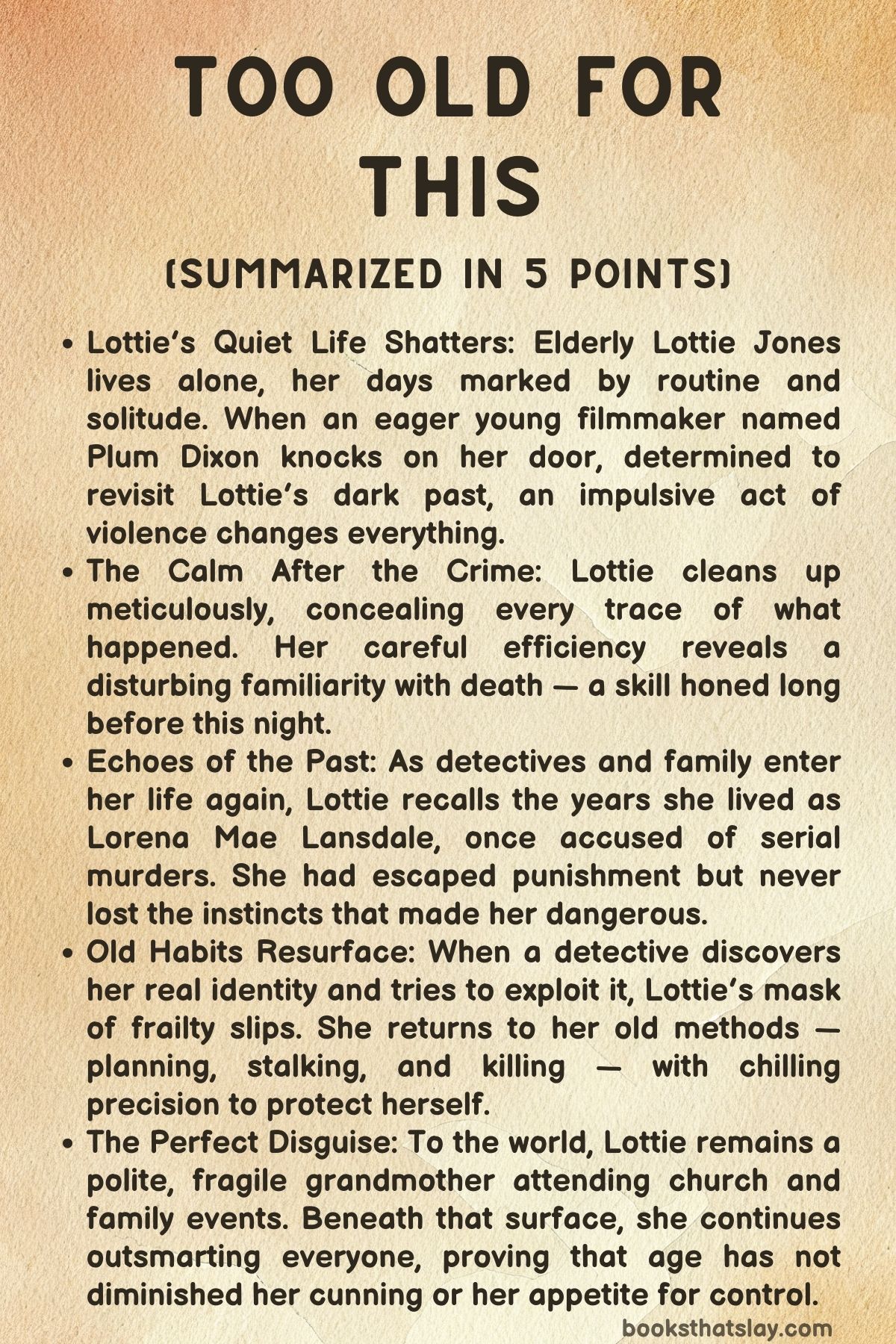

Too Old For This by Samantha Downing is a darkly witty psychological thriller that turns the typical “sweet old lady” trope on its head. The story follows Lottie Jones, a seemingly frail elderly woman living quietly in a small town, whose polite demeanor hides a history of cold-blooded murder.

When a young documentarian comes knocking to expose her past, Lottie’s long-buried instincts resurface, setting off a chain of cunning cover-ups, manipulations, and fresh kills. Downing crafts a chilling portrait of a woman who has survived by weaponizing her harmless appearance, showing that age hasn’t dulled her lethal precision or her taste for control.

Summary

Lottie Jones lives alone in a decaying house that mirrors her own slow decline. Her quiet life is disrupted when Plum Dixon, a young documentary producer, appears at her door.

Plum insists she’s producing a series about unsolved crimes and wants to feature Lottie’s story—how she was once suspected of several murders but never arrested. Lottie, polite but distant, grows wary as Plum presses for cooperation.

When Plum declares she’ll proceed with or without Lottie’s permission, Lottie responds by striking her dead with an umbrella.

Calmly and methodically, Lottie cleans the mess. She erases blood stains with hydrogen peroxide, hides Plum’s body in the garage freezer, and disposes of her electronics to eliminate tracking data.

To disguise evidence, she drives Plum’s car to the airport, discards incriminating items, and returns home to rest before dismembering the corpse. The next day, she uses her chainsaw to cut up the frozen remains, labeling the packages in her freezer as assorted meats.

A call from her son Archie interrupts her work—he announces that his younger girlfriend Morgan is pregnant and they plan to marry. Lottie congratulates him, masking disapproval over his impulsive choices.

Burning Plum’s belongings that evening, Lottie finds the file her visitor brought. The notes reveal that Plum’s documentary was centered on “The Tragedy of Lorena Mae Lansdale,” Lottie’s former identity.

In the 1980s, Lorena was accused of being a serial killer after several murders in Spokane. Interrogated but never charged, she became a media target and vanished after changing her name.

Now, reading those notes, Lottie recalls with detached satisfaction that she was indeed guilty of the crimes.

For days, she continues disposing of Plum’s remains in her fireplace, masking the odor with herbs from her garden. When Plum’s boyfriend, Cole Fletcher, calls to report her missing, Lottie pretends sympathy and claims Plum left her home unharmed.

Later, when detectives Rey Tula and Kelsie Harlow arrive to question her, Lottie plays the frail old woman, serving them coffee and recounting a rehearsed version of events. Her poise and attention to detail convince them she’s harmless.

Once alone, she reflects with amusement at how easily she still deceives people.

As days pass, Lottie resumes her routines—church gatherings, potlucks, gossiping with friends—but her mind remains sharp and calculating. When she reviews Plum’s file again, she notices a recurring name: Detective Kenneth Burke, the officer who interrogated her decades ago.

Memories surface of the first man she killed—Gary, a bank customer who mocked her age after sleeping with her. His death, staged as an accident, awakened something in her that never faded.

Over the years, she repeated the pattern whenever someone humiliated or angered her.

Soon, Detective Kelsie returns alone, her tone more probing. She hints that Plum never boarded a flight and subtly suggests suspicion.

Then she reveals Lottie’s old license photo and real name, proving she knows Lottie’s identity. Instead of panicking, Lottie stays composed, realizing Kelsie has no proof.

But when Kelsie later returns and demands $50,000 in exchange for silence, Lottie understands she’s being blackmailed. Pretending compliance, she invites Kelsie back under the pretense of paying her, then kills her with a hammer.

She stages the scene as an accidental fall in the bathtub, scrubbing away evidence before resting peacefully.

As the investigation into Plum’s disappearance drags on, Lottie distracts suspicion by subtly manipulating those around her. She prank-calls Plum’s mother, Norma, using disguised voices to create confusion, and sends anonymous notes to deepen her paranoia.

Meanwhile, she contemplates moving into a retirement home called Tranquil Towers, wondering whether old age might finally slow her down. But when Norma arrives unexpectedly, bringing dinner and accusations, Lottie’s instincts resurface.

Norma claims to know Lottie’s true identity and has drugged her food to extract a confession. When Lottie awakens bound to a chair, she feigns distress, convincing Norma to loosen the ropes.

Taking advantage of the opening, Lottie kills her and hides the body in her freezer.

Sorting through Norma’s belongings, Lottie discovers communications with Kenneth Burke, the retired detective who still obsesses over her. Norma had been feeding him updates and encouragement to expose her.

Lottie realizes Plum’s investigation, Kelsie’s blackmail, and Norma’s visit all trace back to Burke’s vendetta.

To clean up the mess, Lottie stages Norma’s continued “existence” online, using her phone to send messages and fake activity. Her efforts are interrupted by an unplanned visit from Morgan, her son’s fiancée, who spends the night.

Lottie masks her frustration, playing the gracious host while hiding evidence. After Morgan leaves, she resumes forging Norma’s digital trail, making it appear that Norma and Burke are still communicating.

Determined to end Burke’s interference, Lottie drives to the Dew Drop motel, using Norma’s identity as cover. There, she prepares witnesses to remember “Norma Dixon.” Late at night, someone breaks into her room—a man she subdues with a stun gun. The intruder turns out to be Burke’s son, sent to erase evidence of his father’s illegal surveillance.

Under questioning, he reveals that Burke found Lottie last year through a photo Morgan posted online and had manipulated Plum into pursuing her. When he taunts her about killing Plum, Lottie ends the interrogation with a hammer strike and sets the room ablaze to destroy the body.

She drives to Spokane and confronts the elder Burke, who greets her with a gun but is too frail to use it effectively. During their tense exchange, he demands confessions, boasting that he’s finally trapped her.

She refuses to admit anything and instead manipulates him into lowering his guard. Grabbing his weapon, she strikes him unconscious, plants evidence linking him to the previous deaths, and sets fire to the house, leaving him to perish.

With Burke dead and his home destroyed, Lottie returns to her quiet life. She follows news of the fire, confident that authorities will blame Burke for the chain of killings.

Soon after, Archie’s wedding to Morgan brings her brief peace. Surrounded by friends who see her as a sweet grandmother, she savors her triumph.

When Cole, Plum’s boyfriend, approaches her later with a proposal to finish Plum’s documentary, she considers killing him but decides otherwise. Instead, she suggests working together to produce a new series about the “wrongfully accused.

As Cole agrees, unaware of her true nature, Lottie smiles—content, unrepentant, and still in control. Beneath her gentle appearance, the predator remains, sharper and more dangerous than ever.

Characters

Lottie Jones (Lorena Mae Lansdale)

Lottie Jones stands at the dark center of Too Old For This, embodying a chilling duality—an elderly woman who outwardly represents frailty and respectability but harbors a cold, predatory intelligence beneath her genteel surface. Once known as Lorena Mae Lansdale, she was the prime suspect in a string of murders decades earlier but managed to escape conviction through silence and cunning.

Lottie’s life since then has been one of reinvention: a quiet existence in a modest home, where her neighbors see only a sweet, aging widow. Yet beneath this mask, she remains methodical and remorseless, viewing murder as a rational solution to inconvenience or insult.

Her killings—from impulsive acts of rage to meticulously planned murders—are carried out with a detached precision that underscores her psychopathic nature. She feels no guilt, only the satisfaction of maintaining control and evading exposure.

What makes Lottie especially compelling is her self-awareness; she recognizes the decaying limits of her body but also takes pride in her intellect’s enduring sharpness. Even as her world modernizes with surveillance and digital footprints, she adapts—learning, deceiving, and manipulating until the end.

Ultimately, Lottie is a study in sustained darkness, a woman who refuses to succumb to age or morality, finding perverse purpose in the very acts that should have destroyed her.

Plum Dixon

Plum Dixon represents youthful ambition colliding fatally with the dangerous allure of truth. As a young documentarian eager to expose old crimes, she sees herself as a seeker of justice and fame.

Her fascination with Lottie’s past stems not from empathy but from the thrill of uncovering a notorious mystery, and this hubris leads to her demise. Plum’s persistence, though admirable in principle, reveals her naiveté—she underestimates the woman she confronts, assuming that age equates to vulnerability.

Her murder serves as the novel’s inciting act, setting off the resurgence of Lottie’s dormant instincts. In death, Plum becomes both victim and catalyst: the spark that reignites a monster’s legacy.

Through her character, the book critiques modern sensationalism, showing how true-crime storytelling, when stripped of humanity, can blur the line between curiosity and recklessness.

Detective Kelsie Harlow

Detective Kelsie Harlow emerges as a mirror to Lottie in many ways—ambitious, intelligent, and willing to bend rules to achieve her goals. Initially introduced as a diligent investigator re-examining Plum’s disappearance, she gradually reveals a personal agenda rooted in greed and desperation.

When she uncovers Lottie’s true identity, she sees not justice but opportunity, attempting to blackmail the elderly woman for money. Kelsie’s moral decay reflects the novel’s broader theme of corruption across generations; while Lottie kills to maintain control, Kelsie manipulates the law she swore to uphold for personal gain.

Her arrogance and underestimation of Lottie’s ruthlessness lead to her downfall. In a grim symmetry, Kelsie becomes yet another victim of her own ambition, proving that cunning without wisdom is fatal in Lottie’s world.

Detective Rey Tula

Detective Rey Tula serves as Kelsie’s professional counterbalance—a figure of integrity and procedure. Though less prominent, he represents the conventional face of justice that Lottie continually eludes.

His interactions with Lottie are marked by civility and trust, qualities she exploits to reinforce her guise as a harmless old woman. Unlike Kelsie, Tula lacks personal motives, which makes him a moral touchstone in the story’s landscape of deceit.

His inability to see through Lottie’s act underscores the novel’s cynical view of perception—how charm, age, and social assumptions can obscure evil in plain sight.

Norma Dixon

Norma Dixon, Plum’s mother, embodies grief’s descent into obsession. Her loss transforms her into a vigilante investigator, driven not by justice but by vengeance and guilt.

Unlike her daughter, Norma’s pursuit of truth is emotional rather than professional; she becomes consumed by the need to find someone to blame. Her confrontation with Lottie culminates in a reversal of power—her attempt to expose a killer ends in her own death, executed with the same brutal efficiency that defines Lottie’s past crimes.

Norma’s tragedy lies in her humanity; she underestimates the depths of the darkness she’s confronting. Her downfall reinforces the theme that in Lottie’s world, empathy and morality are vulnerabilities, not virtues.

Kenneth Burke

Kenneth Burke, the retired detective who once investigated Lottie, represents the obsessive persistence of a man unable to accept defeat. His decades-long fixation on proving Lottie’s guilt corrodes his sense of duty, transforming justice into vengeance.

Even in old age, Burke’s life revolves around the woman who eluded him. His manipulation of Plum and Norma to reopen the case reveals the moral compromise that obsession breeds.

When Lottie finally confronts him, the reversal is complete: the once-powerful detective is now frail, confined to a wheelchair, and undone by the very woman he sought to destroy. His death—staged as an accident within his own trap—illustrates how his obsession has rendered him powerless, consumed by the monster he created.

Archie Jones

Archie Jones, Lottie’s son, embodies innocence corrupted by proximity to evil. Though unaware of his mother’s crimes, his life has been shaped by her manipulations—first through the forced name change and relocation after her earlier scandals, then through her emotional control disguised as maternal devotion.

Archie’s kindness and optimism contrast starkly with Lottie’s amorality, highlighting the emotional void at her core. His relationship with Morgan and impending fatherhood introduce the theme of generational continuation—suggesting that while Lottie’s darkness may not pass directly to him, the lies she built will haunt his lineage.

Archie is the closest thing to a moral anchor in Lottie’s life, yet even he is not spared her deception.

Morgan

Morgan, Archie’s fiancée, introduces a refreshing honesty to the otherwise deceit-filled narrative. She is young, impulsive, and sincere—everything Lottie once was not and never could be.

Her candidness unsettles Lottie, who oscillates between judgment and reluctant admiration. Morgan’s presence forces Lottie to confront her own aging and isolation; she sees in Morgan a version of the life she forfeited when she chose control over connection.

While Morgan remains peripheral to the central murders, her role as the emotional catalyst for Archie—and her brief, uneasy coexistence with Lottie—adds a note of humanity and contrast to the protagonist’s chilling detachment.

Cole Fletcher

Cole Fletcher, Plum’s boyfriend, functions as both a narrative device and a moral counterpoint. His grief and confusion humanize the aftermath of Plum’s disappearance, illustrating how Lottie’s crimes ripple outward, destroying lives she barely acknowledges.

His visits to Lottie’s home create moments of irony and tension, as he confides his sorrow to the very woman responsible for his loss. By the novel’s end, Cole’s decision to continue Plum’s documentary project and collaborate with Lottie serves as a final, haunting twist.

It suggests that evil not only survives but reinvents itself—now through storytelling, as Lottie crafts a sanitized version of her legacy. His unwitting partnership with her becomes the ultimate testament to her manipulative genius.

Themes

Age and Power

Lottie Jones’s age in Too Old For This functions as both a disguise and a weapon. Her elderly appearance allows her to pass unnoticed, to manipulate assumptions of frailty and innocence that society assigns to older women.

Downing uses this perception gap to expose how power can exist beneath the surface of vulnerability. Lottie’s deliberate use of her walker, her soft-spoken demeanor, and her careful mimicry of social niceties make her invisible in plain sight.

She is underestimated by the younger people around her — detectives, neighbors, even her own son — which becomes her greatest advantage. Beneath the image of the grandmotherly recluse lies a predator who understands the social dynamics of age and weaponizes them.

The narrative reveals how aging, often seen as a decline of control, can in fact become a site of renewed authority when one learns to exploit others’ underestimation. Yet the power she wields is steeped in bitterness; her killings are less about rage and more about preserving autonomy in a world that has written her off.

The theme underscores the intersection of gender, age, and perception — the ways in which a woman’s invisibility in old age can paradoxically render her untouchable.

Identity and Reinvention

Lottie’s transformation from Lorena Mae Lansdale to Lottie Jones lies at the heart of the story’s meditation on identity. Her decision to change names and relocate after escaping prosecution for murder illustrates the human instinct to rewrite oneself when the past becomes unbearable.

But the reinvention is hollow — a mask that conceals guilt rather than erases it. Downing presents identity as something mutable yet haunted, suggesting that self-reinvention can never be clean when the past remains unresolved.

Lottie’s meticulous maintenance of her façade — the tidy house, the church socials, the routine grocery runs — acts as a daily performance of normalcy. Beneath it, she carries the weight of memory and the thrill of deception.

Her identity is not only about survival but about control over narrative: who she appears to be versus who she is. When the younger generation — Plum, Kelsie, Norma — attempt to expose her, each confrontation forces Lottie to defend not only her freedom but her constructed self.

In reclaiming her identity through violence, she both destroys and reaffirms it. The theme exposes how identity, once fractured by shame and notoriety, becomes a lifelong project of concealment.

The Illusion of Innocence

The novel dismantles the comforting myth that evil is visible or that innocence is tied to appearance. Lottie’s charm, civility, and social grace serve as camouflage for her moral emptiness.

Downing’s portrayal of her calm after murder — making tea, attending bingo, chatting with friends — makes the reader uneasy precisely because it feels ordinary. The façade of decency is sustained through habit, not remorse.

This theme questions the human tendency to equate gentleness with goodness and composure with morality. Every person Lottie interacts with believes in her kindness because they need to; they depend on the idea that danger announces itself.

Downing exploits this collective blindness, showing that people often ignore what doesn’t fit their expectations. The illusion of innocence becomes a broader commentary on how society romanticizes the elderly, especially women, as harmless.

Lottie’s existence refutes that myth. Her murders are planned, reasoned, and precise, performed without emotional justification.

Through her, Downing redefines innocence not as the absence of guilt but as the product of perception — a story the world tells itself to stay comfortable.

Memory, Guilt, and Justification

Memory in Too Old For This is selective, strategic, and self-serving. Lottie remembers her crimes in fragments, often without remorse, and reshapes them to fit a personal moral code.

Her recollections serve less as confession than as justification — a way to maintain psychological equilibrium. Downing uses this manipulation of memory to explore the nature of guilt: whether it diminishes with time or simply becomes easier to rationalize.

Lottie’s calm reflection on decades-old murders, her ability to narrate them as anecdotes rather than tragedies, reveals how guilt corrodes differently when left unpunished. The absence of external accountability allows her to construct internal logic — she kills because people are rude, disrespectful, or intrusive, and in her mind, these are legitimate provocations.

Her memory thus becomes a narrative device that protects her ego. Yet subtle cracks appear in her control when she confronts echoes of her past — Burke’s persistence, Plum’s documentary, Norma’s accusations.

Each intrusion threatens to collapse her carefully maintained amnesia. The theme captures how guilt is not a static emotion but a living thing that shifts shape to keep its host intact, until reality finally exposes the rot underneath.

Gender and Perception

Through Lottie, Downing dissects the expectations placed on women, particularly older ones, to remain accommodating, pleasant, and invisible. The protagonist’s violence becomes a distorted rebellion against these expectations.

Her earlier murders often stem from being insulted or dismissed by men, moments where her age and gender reduce her to an object of ridicule. By killing them, she reclaims the power denied to her — a grotesque assertion of dignity in a society that infantilizes or mocks older women.

The story thereby reimagines gendered rage not as emotional chaos but as calculated correction. Downing does not ask readers to sympathize with Lottie but to confront the forces that make her invisibility both protective and dehumanizing.

Even her manipulative politeness — the tea, the smiles, the grandmotherly routine — mirrors the survival mechanisms women learn: to placate, to soothe, to conceal true emotion beneath performance. The theme thus reveals how femininity itself becomes an armor and a disguise, capable of both deflection and destruction.

In the end, Lottie embodies the dark potential of conformity — the violence that can emerge when a lifetime of repression finds its outlet under the guise of gentleness.