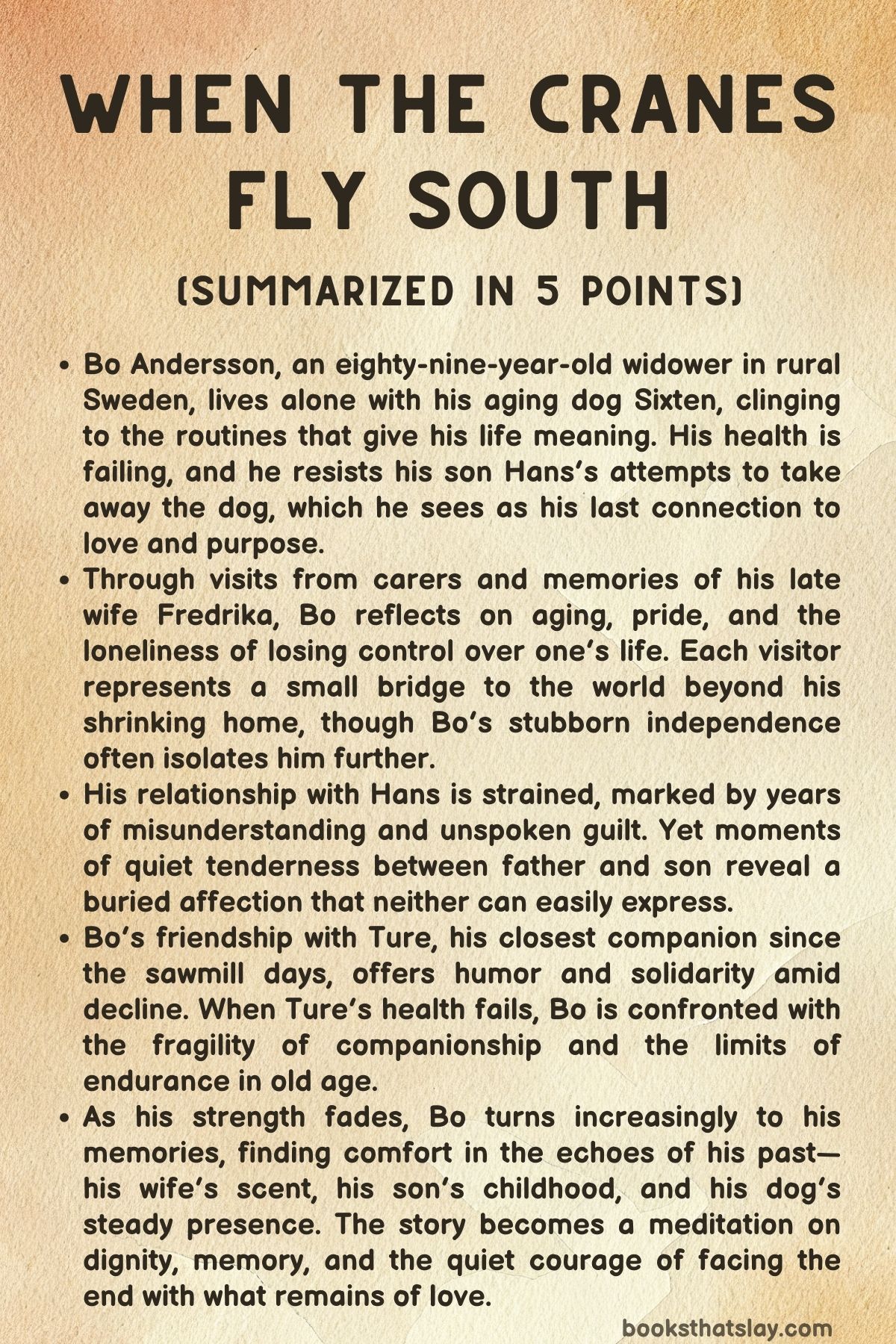

When the Cranes Fly South Summary, Characters and Themes

When the Cranes Fly South by Lisa Ridzen is a moving portrayal of aging, memory, and the quiet dignity of human endurance. Set in rural Sweden, the novel follows Bo Andersson, an eighty-nine-year-old widower whose life has contracted to the small rhythms of his home, his loyal dog Sixten, and the past that lingers like frost on his windows.

Through alternating present scenes and recollections, Ridzen explores family estrangement, loss, and the frailty of independence. With a voice both tender and restrained, the book examines how love and loneliness entwine in old age, and how even in fading light, small acts of care still hold meaning.

Summary

Bo Andersson lives alone in his wooden house in the Swedish countryside, his only constant companion his elderly dog, Sixten. Age has caught up with Bo—his body aches, his eyesight dims, and memory often slips—but he clings to his routines and independence.

His son Hans, increasingly anxious about Bo’s health, urges him to move to assisted living and give up Sixten, arguing that his father can no longer manage. Bo resists fiercely, believing that as long as Sixten remains, so does his purpose.

His days are punctuated by visits from carers such as Ingrid, Kalle, and Johanna, who check on him, prepare meals, and log their observations in a notebook. Ingrid, kind and patient, becomes Bo’s favorite, offering small kindnesses that ease the sharp edges of solitude.

When Hans pressures him about Sixten, Bo vents to her, grateful for someone who listens without judgment. Each evening, he sits by the fire, surrounded by the ghosts of his past—his wife Fredrika, now lost to dementia, his youth at the sawmill, and the long friendship with his coworker Ture.

When Sixten disappears one morning, Bo is distraught. He calls Ture, and the two reminisce, their conversation meandering through decades of shared history.

Carers note Bo’s distress, and neighbors join the search. Eventually, Marita, a kind local woman, tracks Sixten down through a Facebook post, returning him safely.

Bo’s joy at their reunion restores a flicker of vitality. But the relief is temporary.

His health continues to falter; he grows confused and tired more often. He looks forward to a planned visit to Fredrika at her nursing home, hoping for a sign of recognition.

During the visit, Fredrika mistakes both her husband and son for strangers, and the encounter devastates Bo. He forces a smile, recalling the woman she once was—warm, sharp-witted, the heart of their home—and realizing that she is gone in all but body.

On the drive back, he and Hans share a fragile calm. They talk about Ellinor, Bo’s granddaughter, and for a brief moment, there’s warmth between them.

Yet the tension soon returns. Hans’s life, neat and modern, stands in stark contrast to Bo’s cluttered existence.

Their political and generational differences remain unhealed scars from years past.

Back home, Bo finds comfort in Sixten’s presence. But Hans and the local services persist in their concern.

When they replace Bo’s beloved daybed with an electric hospital bed “for his safety,” he feels humiliated, stripped of control. Even sleep no longer belongs to him.

One afternoon, determined to prove his strength, Bo takes Sixten into the woods. The familiar paths of his youth lead him too far; he falls, disoriented and weak, until Johanna and Ingrid find him.

Their gentle care helps him home, but the incident triggers an official report. Bo realizes his independence is eroding—soon, they might take Sixten too.

Panicked, he phones Ture, confessing that he couldn’t bear to live if they took his dog. Ture comforts him, though he too is weakening.

Their friendship, bound by years of laughter and quiet endurance, now centers on shared frailty. When Ture stops answering calls, Bo grows desperate and finally asks Hans to check on him.

Hans learns that Ture has died. Delivering the news, he finds his father weeping, stripped of his last peer.

Bo’s loneliness deepens, and he spends his days staring at the lake, haunted by silence.

At Ture’s funeral, Bo insists on attending. Dressed carefully, he pins a badge of the mythical Storsjö Beast to his jacket—a private tribute to their jokes.

The sparse congregation includes a stranger, Eskil, whom Bo suspects was more than a friend to Ture. The realization that Ture had hidden parts of his life stings, but Bo is too tired for jealousy.

After the ceremony, he and Hans share coffee and quiet conversation. For a few moments, the distance between them narrows.

As autumn arrives, Bo’s decline accelerates. He grows weaker, sleeping for hours, refusing food.

His carers continue their visits, offering warmth, small talk, and soup. Ingrid reads to him, opens the window for fresh air, and tends to his dignity.

The priest visits, bringing a potted red flower. Though Bo claims not to believe, he finds comfort in her presence.

Memories crowd his fading mind—his mother’s hands, Fredrika’s laughter, his father’s scolding voice, the smell of sawdust and winter apples. The house, once full of life, now holds only echoes.

Ellinor visits, her presence bright and youthful. They talk about her studies, her future, and Bo’s stories of the past.

He tells her that he is proud of her, and when Hans arrives later, Bo musters the strength to say the same to him. For the first time, father and son speak without argument.

Hans takes his hand, tears welling, and tells Bo that Fredrika would be proud too.

That night, the house is still. Ingrid sits by his bedside, reading quietly.

Sixten, long absent, is suddenly there again—whether in truth or vision, it doesn’t matter. The dog curls beside him, warm and solid.

Bo’s hand rests on Sixten’s back as his breathing slows. Ingrid records in the logbook that Bo died peacefully at 3:30 a.m. , his hand still on his faithful companion.

Outside, the cranes are flying south, and the quiet home by the lake is finally at rest.

Characters

Bo Andersson

Bo Andersson stands at the heart of When the Cranes Fly South, embodying the frailty, stubbornness, and dignity of old age. An eighty-nine-year-old widower, Bo’s life is a quiet struggle against decline—both physical and emotional.

His days are steeped in routine and memory, bound tightly to his home, his faithful dog Sixten, and the ghosts of his past. Bo’s relationship with aging is marked by resistance; he refuses to yield to his son Hans’s well-meaning control or to the carers’ insistence that he surrender his independence.

The loss of autonomy terrifies him more than death itself, and every act of defiance—from refusing a nappy to keeping his fire lit—becomes a declaration of selfhood. Bo’s memories of his late wife Fredrika, his harsh father, and his years at the sawmill shape his introspective world, where past and present blur into one another.

His emotional life is rich despite his isolation—his affection for Sixten, his friendship with Ture, and his growing tenderness toward Ingrid reveal a man still capable of deep love and loyalty. In his final days, Bo’s acceptance of mortality is quiet and profound; he faces death not with fear but with a yearning for reunion—with Fredrika, with his memories, and with the life that once gave him meaning.

Hans Andersson

Hans, Bo’s only son, represents the complicated tension between love and control in family caregiving. A man caught between duty and frustration, Hans is torn by guilt over his father’s decline and anger at Bo’s obstinacy.

Their relationship, scarred by old conflicts, reflects a generational struggle between independence and responsibility. Hans’s insistence on safety—the removal of Sixten, the replacement of Bo’s bed—comes from concern, yet it also exposes his discomfort with vulnerability and his inability to bridge emotional distance.

His childhood memories of Bo’s strictness still shadow him, and even as an adult, he unconsciously repeats patterns of paternal dominance. However, beneath the frustration lies genuine care.

His small gestures—keeping old family photographs, comforting Bo at Ture’s funeral, holding his hand near the end—reveal a love that words often fail to express. By the novel’s close, Hans’s reconciliation with his father is understated yet deeply moving, symbolizing forgiveness and continuity across generations.

Fredrika Andersson

Fredrika, though absent for most of the narrative, remains an emotional presence that permeates Bo’s thoughts and memories. Once a lively and compassionate woman, Fredrika’s decline into dementia transforms her into both a figure of love and loss.

Her absence defines Bo’s loneliness, and her presence in his memories gives him solace and sorrow in equal measure. Through Bo’s recollections, she emerges as his emotional anchor—the person who softened his rough edges and grounded his temper.

Even as she forgets him, Bo clings to her memory, preserving her scent in a jar and her image in his mind as a symbol of enduring love. Fredrika’s dementia also mirrors Bo’s own fading clarity, turning their separation into a haunting reflection of time’s cruelty.

In the end, she becomes the embodiment of both life’s tenderness and its inevitable decay.

Sixten

Sixten, Bo’s elderly dog, serves as the most potent symbol of loyalty and companionship in When the Cranes Fly South. More than a pet, Sixten represents Bo’s last living connection to his past, his freedom, and his sense of purpose.

The bond between man and dog is profound—Sixten’s presence gives structure to Bo’s days and comfort to his solitude. When Hans insists that Sixten must be rehomed, Bo’s resistance becomes a fight for his very identity.

Sixten’s disappearance and eventual return parallel Bo’s emotional journey: the loss of control, the confrontation with mortality, and the fragile triumph of love. In Bo’s final moments, Sixten’s warmth at his side signifies peace and completion—the faithful companion who accompanies him to the threshold of death.

Ture

Ture, Bo’s lifelong friend, represents the shared history and humor that sustain human connection even in old age. A man of eccentric charm and plainspoken wisdom, Ture mirrors Bo’s stubborn independence while offering a gentler balance to his friend’s temper.

Their conversations—by phone or in memory—blend nostalgia with dark humor, revealing an enduring friendship rooted in shared experiences at the sawmill and a mutual understanding of life’s hardships. Ture’s illness and eventual death mark one of the novel’s most devastating turns, stripping Bo of his last peer and confidant.

Yet Ture’s memory lingers as a testament to the resilience of friendship and the quiet dignity of those who face life’s end without illusion.

Ingrid

Ingrid, one of Bo’s carers, emerges as a figure of compassion and quiet strength. Her patience and empathy bridge the generational and emotional gaps that others fail to cross.

To Bo, she becomes a surrogate daughter—a presence that combines professionalism with genuine affection. Her gentle humor and attentiveness restore Bo’s sense of humanity in a world that increasingly treats him as an object of care rather than a person.

Ingrid’s tenderness in his final days—feeding him, reading to him, arranging the room with small comforts—underscores her deep respect for his dignity. It is she who ensures that Bo’s last hours are marked by peace rather than fear, standing as the moral heart of the novel.

Johanna, Kalle, and Sofia

The other carers—Johanna, Kalle, and Sofia—collectively represent the everyday humanity of the caregiving world. Each, in small gestures, contributes to Bo’s sense of continuity: Johanna’s teasing lightens his mood, Kalle’s stories of church biscuits evoke simpler times, and Sofia’s gentle humor brings laughter to moments of frailty.

They form a quiet chorus of kindness, contrasting the bureaucratic systems that threaten Bo’s autonomy. Through them, the novel highlights the delicate balance between professional duty and genuine compassion in elder care.

Ellinor

Ellinor, Bo’s granddaughter, symbolizes the bridge between generations—a link to the future that Bo both cherishes and mourns. Her visits inject youth and brightness into Bo’s dimming world, though her alignment with Hans over Sixten’s removal deeply wounds him.

Yet her affection remains sincere, and her final words of love near his death offer him peace and continuity. Ellinor’s presence evokes both the persistence of family ties and the inevitability of change, suggesting that love, even when complicated, endures beyond misunderstanding.

Marita

Marita, the neighbor who helps find Sixten, serves as a fleeting but significant figure of community and compassion. Her kindness contrasts with Bo’s isolation, reminding readers that empathy can emerge from unexpected places.

Through her small acts—bringing flowers, spreading word about Sixten—Marita reinforces the novel’s quiet faith in human decency.

Themes

Aging and the Loss of Autonomy

In When the Cranes Fly South, Lisa Ridzen paints a painfully intimate picture of aging as a gradual surrender of control. Through Bo Andersson’s experiences, the narrative captures not only the physical deterioration that comes with old age but also the erosion of independence that wounds the spirit more deeply than any illness.

Bo’s body becomes a vessel of limitation—his trembling hands, faltering eyesight, and unsteady gait signal his loss of command over the simplest actions. Yet what unsettles him most is how others, especially his son Hans and the home carers, begin to make decisions for him.

Each well-intentioned act of care feels like another small confiscation of his dignity. The replacement of his old wooden daybed with a hospital bed, his resistance to wearing nappies, and his fight to keep his dog Sixten all illustrate his desperate attempt to cling to some semblance of self-governance.

Ridzen doesn’t romanticize Bo’s stubbornness; instead, she renders it as the last assertion of a man who once built, worked, and provided, now reduced to compliance and supervision. The novel questions what it means to live when one’s choices are quietly taken away in the name of safety.

Bo’s decline is not just a medical condition—it is a spiritual battle against invisibility, where the world around him has reclassified him from an agent of action to an object of care. Aging, in Ridzen’s hands, is not merely the passage of time but the relentless negotiation between dependency and self-respect.

Memory and the Persistence of the Past

Memory shapes the emotional landscape of When the Cranes Fly South, guiding Bo’s perception of the present as much as it connects him to what he has lost. The novel is built from the fragments of his recollections—his youth at the sawmill, the tense lessons from his father, his marriage to Fredrika, and the laughter of his son as a child.

These recollections are not linear but arrive in scattered, sensory flashes, often triggered by familiar sounds, smells, or textures. Through this ebb and flow of memory, Ridzen shows how the past refuses to remain buried, how it loops endlessly within the consciousness of an aging man whose present has grown narrow and repetitive.

Memory becomes both comfort and torment for Bo: the warmth of his wife’s scarf offers solace, yet the memory of arguments with Hans fills him with regret. The blurred boundaries between past and present mirror his fading grasp on time, as if memory itself becomes his final terrain of freedom.

Ridzen’s portrayal of memory is deeply human—it is flawed, selective, and subjective, yet it holds the emotional truth of Bo’s life more vividly than his current surroundings ever could. Even as his body weakens, Bo’s memories sustain his identity, proving that the self endures not through what one can do, but through what one can remember and feel.

Companionship and Isolation

Loneliness dominates Bo’s existence, punctuated by fleeting moments of connection that only emphasize its depth. His house in rural Sweden becomes a quiet stage where isolation echoes in every room, and Sixten, his aging dog, stands as his only constant companion.

Through this relationship, Ridzen explores the human need for attachment when all other bonds fray. Sixten’s presence offers Bo not just company but continuity—a reminder of life’s former rhythm, of mornings spent walking, of shared rituals that affirm his place in the world.

When Hans insists on taking Sixten away, the threat is not merely the loss of a pet but the destruction of Bo’s last emotional tether. Yet Ridzen does not frame isolation solely as a punishment; she portrays it as an inevitable part of the human condition.

Even surrounded by carers and family, Bo remains profoundly alone, trapped within his own memories and decline. His friendship with Ture, maintained through phone calls and recollections, is another fragile connection to meaning.

When Ture dies, the loneliness becomes absolute, and Bo’s world collapses inward. Through these relationships, Ridzen captures the paradox of companionship—that it both alleviates and magnifies solitude, reminding Bo of what he has and what he has lost.

The novel’s quiet tragedy lies in the realization that true companionship, in the end, is not found in words or presence, but in shared memory and enduring love.

Family, Generational Divide, and Reconciliation

The strained relationship between Bo and Hans anchors the emotional heart of When the Cranes Fly South. Their interactions are laden with decades of unspoken tension, shaped by pride, misunderstanding, and the long shadow of paternal authority.

Bo once ruled his household with firmness inherited from his own father, and now, in old age, he finds the roles reversed—Hans assumes control, making decisions about his care, his home, and his dog. This reversal of power fuels Bo’s resentment and grief, as he grapples with being treated like the dependent child he once chastised.

Ridzen captures this generational friction not as cruelty but as the painful inevitability of familial love—where concern and control often blur. Yet beneath their clashes runs a quiet current of affection and regret.

Moments such as Hans finding the old fishing tackle box or sharing coffee after Fredrika’s visit reveal their mutual longing for reconciliation. Ridzen does not offer sentimental resolution; instead, she allows their bond to mend in small gestures—a touch on the knee at Ture’s funeral, a simple exchange of pride and forgiveness near the end.

The theme of family thus evolves into an exploration of continuity and inheritance: the ways we echo those who raised us, the mistakes we repeat, and the hope that compassion can outlast pride. Through Bo and Hans, Ridzen captures the universal ache of parents and children struggling to love one another in the language of their own stubbornness.

Death, Acceptance, and the Meaning of Peace

Death hovers over every page of When the Cranes Fly South, not as an abrupt event but as a slow descent toward stillness. Ridzen treats mortality not with melodrama but with quiet inevitability, mirroring the rhythm of Bo’s dwindling life.

His death is preceded by countless small endings—the loss of mobility, of his dog, of his best friend, and finally of his ability to distinguish dreams from memory. Each of these moments serves as a rehearsal for the final one, teaching him, and the reader, that dying is not a single act but a gradual surrender.

Yet within this surrender lies a profound sense of peace. Bo’s last hours, marked by tenderness from Ingrid, the presence of Hans and Ellinor, and the imagined—or perhaps real—return of Sixten, transform death from an adversary into a gentle reconciliation with life itself.

Ridzen’s treatment of death emphasizes continuity rather than cessation: the warmth of the dog’s fur, the scent of Fredrika’s scarf, and the candle’s flicker all evoke a transition rather than an end. Bo’s final acceptance restores his agency; by choosing calm over resistance, he reclaims the dignity that frailty had stolen.

In his quiet passing, Ridzen offers a meditation on the human condition—that life’s meaning is not in the struggle to survive, but in the grace to let go when the cranes, symbols of migration and return, finally fly south.