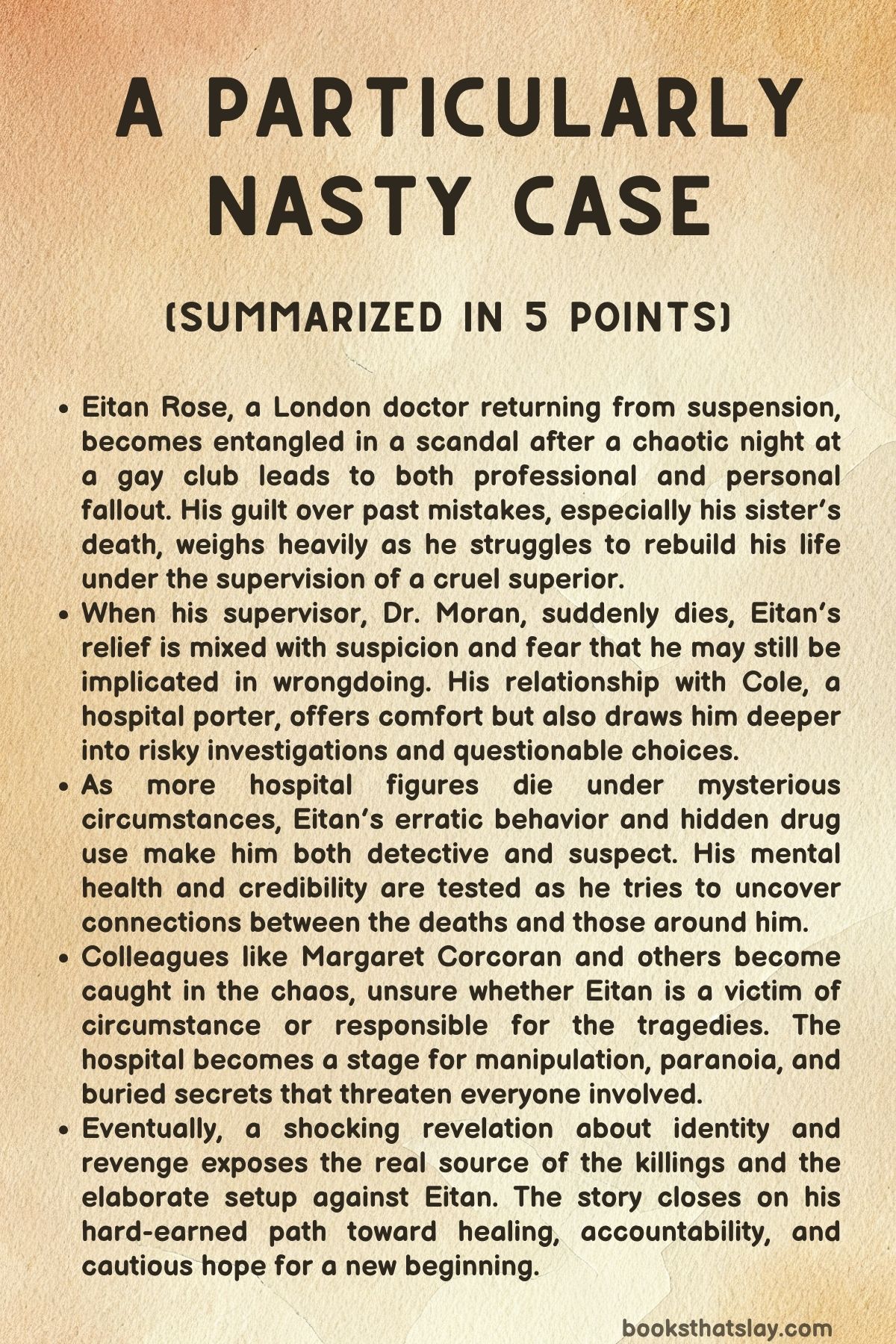

A Particularly Nasty Case Summary, Characters and Themes

A Particularly Nasty Case by Adam Kay is a darkly comic medical thriller that blends psychological tension, moral complexity, and biting satire of the British healthcare system.

The novel follows Dr. Eitan Rose, a middle-aged rheumatologist trying to rebuild his life after a breakdown and professional disgrace. When his despised supervisor dies suddenly, Eitan becomes entangled in a spiraling mystery involving drugs, deceit, and death within his hospital. As more colleagues fall victim to mysterious cardiac events, Eitan’s fragile recovery collapses into obsession, paranoia, and self-destruction. Witty, unsettling, and painfully human, the novel explores guilt, stigma, and the blurry line between sanity and truth.

Summary

Dr. Eitan Rose begins his story in a haze of alcohol and regret.

One drunken night in South London, he meets an older man named Chester, who leads him into a gay bathhouse called “Purgatory. ” When a man collapses during sex, Eitan instinctively performs CPR and saves his life but panics when paramedics arrive, lying about his identity.

By morning, his hangover is brutal—and worse, it’s his first day back at St Jude’s Hospital after a suspension for drug abuse and a manic episode. Returning to work, he’s mocked by his new supervisor, Dr. Douglas Moran, whose name ironically matches the alias Eitan used the night before.

Haunted by guilt over his sister Elodie’s death years earlier, Eitan tries to stay professional but struggles under Moran’s cruel oversight. He meets Cole, a flirtatious hospital porter, who brings him rare comfort.

Yet his probationary period is rocky: Moran monitors his clinics, criticizes him constantly, and manipulates him emotionally, even using Elodie’s death to humiliate him. Under pressure, Eitan secretly turns again to cocaine, disguised in a nasal spray.

When Moran dies suddenly of a heart attack just after catching Eitan and Cole half-naked in his office, Eitan feels both horror and relief—the man who could destroy him is gone.

Still, paranoia takes hold. Afraid Moran might have left incriminating evidence, Eitan and Cole break into Moran’s office at night, discovering his widow, Dr.

Davina Hallowell, retrieving suspicious items. They also find Moran’s diary, which contains lurid accusations about Eitan’s supposed misconduct.

Investigating further, Eitan suspects Hallowell killed her husband out of jealousy over an affair with a dominatrix named Diana Deluxe. Disguised as a client, Eitan visits her flat, only to be thrown out.

At Moran’s funeral, he secretly examines the body for whip marks but finds none. Caught in the act, he’s accused by Hallowell of indecency and sexual misconduct, worsening his reputation.

Suspended again, Eitan faces disciplinary action. His lawyer ex-boyfriend, Mo, argues his behavior stemmed from untreated bipolar disorder.

Though humiliated, Eitan keeps his job with mandatory therapy. He tries to let go of his obsession, but suspicions resurface—this time about his colleague Margaret Corcoran, whom Moran had once tormented.

When she admits to a past affair with Moran but denies any role in his death, Eitan feels directionless once more.

His attention shifts when Professor Annabel Stein, Moran’s abrasive successor, begins behaving erratically—singing, insulting colleagues, and taking strange interest in Eitan’s nasal spray. When she collapses from a massive heart attack soon after, Eitan becomes convinced someone is murdering hospital leaders.

Stein survives briefly, and when Eitan visits her in intensive care, she scribbles something he interprets as “pharmacist. ” Believing she meant Dave Webb—the man who supplies his drug-laced sprays—Eitan accuses him over the phone.

Moments later, Stein suffers another cardiac arrest and dies.

As his mental state deteriorates, Eitan drags Cole into increasingly wild theories. Cole suspects another doctor, Ciaran Bourke, but learns he has an alibi.

Eitan’s manic delusions worsen; he stops taking medication and impulsively proposes to Cole at a party. His friends fear a relapse.

When he later reads a report revealing Moran’s heart attack was caused by takotsubo cardiomyopathy—a rare stress-induced condition—he sees a pattern linking all the deaths.

Meanwhile, Margaret begins the next section of the narrative, providing a clearer view of Eitan’s chaos. Her routine life is disrupted when police cordon off her office after declaring Moran and Stein’s deaths suspicious.

Rumors spread that Eitan has been arrested. Officers question her about drugs found in his desk—specifically midodrine, a medicine capable of triggering cardiac collapse.

Realizing Eitan’s drawers are unusually tidy, she suspects evidence has been planted.

Margaret contacts Cole, who is devastated over Eitan’s arrest. Together, she and her assistant Nina uncover new clues: Eitan’s Kindle search history shows he looked up “how to cause fatal takotsubo cardiomyopathy” after the deaths, not before, undermining the idea that he researched the method in advance.

Margaret’s phone had also been stolen around the time of Moran’s death, and a message inviting Moran to a secret meeting—one she never sent—was found on his phone.

At a psychiatric tribunal, psychiatrist Ed Nsanze insists Eitan should remain detained, but Margaret’s sharp questioning helps secure his release. She then invites Eitan and Cole for a tense dinner, during which Cole accuses Eitan of murder and drug use.

Margaret, convinced of his innocence, reveals the odd discrepancies in evidence. Moments later, she collapses with chest pain, briefly suspecting Eitan has poisoned her.

Though she survives, her cat dies after Eitan forgets to give its medication, adding to his guilt.

During recovery, Eitan pieces together a revelation. He recalls interviewing medical school applicants years earlier with Moran and Stein—and recognizing one name: Donal Doherty, a rejected candidate.

Comparing an old photo to Cole’s face, he realizes his boyfriend is the same man. When confronted, “Cole” confesses: he is Donal Doherty, who sought revenge against Moran and Stein for rejecting him and destroying his dream of becoming a doctor.

He orchestrated their deaths using midodrine to induce takotsubo cardiomyopathy, planted evidence to frame Eitan, and exploited his bipolar disorder to ensure no one would believe him. Donal even faked Margaret’s poisoning and killed her cat to tighten the frame.

Eitan records the confession using his always-on dictation mic.

In the aftermath, Eitan is exonerated. The hospital apologizes and reinstates him, promising support and drug counseling.

Though scarred by trauma and guilt over Elodie’s death, Eitan begins to heal. He moves in temporarily with Margaret and joins a support group for doctors with bipolar disorder.

Gradually, he opens himself to life again, meeting a kind bookseller named Tom. Wary but hopeful, he starts a cautious new relationship, first ensuring Tom was never a medical applicant.

In the final scene, Eitan visits Elodie’s grave, leaving behind the ring he once wore in her memory. He messages his estranged father, offering to meet for coffee, and browses for a new flat filled with light—a symbol of renewal.

For the first time in years, he looks ahead, no longer defined by guilt, illness, or the wreckage of his past.

Characters

Eitan Rose

Eitan Rose stands at the heart of A Particularly Nasty Case, a middle-aged London rheumatologist whose life is defined by guilt, mental illness, and a desperate search for redemption. Haunted by his sister Elodie’s death — a tragedy he blames himself for — Eitan carries a burden that drives his self-destructive tendencies.

His bipolar disorder, substance abuse, and fragile sense of identity manifest through erratic yet profoundly human behavior. His oscillation between confidence and collapse reveals a man caught between brilliance and breakdown.

Professionally, Eitan is skilled and compassionate, capable of sharp medical insight and empathy for his patients. Personally, however, he is deeply flawed, often self-sabotaging with cocaine use and impulsive relationships.

His romantic entanglement with Cole, later revealed to be Donal Doherty in disguise, encapsulates his vulnerability — a yearning for love and trust that blinds him to danger. By the novel’s end, Eitan’s journey is one of painful enlightenment: he recognizes the cyclical nature of his illness, confronts his trauma, and begins to rebuild both his career and sense of self, symbolized by his decision to look for new housing and reconnect with his father.

Douglas Moran

Douglas Moran, the tyrannical medical director of St. Jude’s Hospital, serves as the novel’s initial antagonist.

A manipulative and sadistic superior, Moran embodies institutional cruelty cloaked in professionalism. His interactions with Eitan are laced with malice, exploiting Eitan’s vulnerability and mental health struggles to assert dominance.

Moran’s hypocrisy is gradually exposed through his own vices — infidelity, alcoholism, and sadomasochistic secrets — painting him as both oppressor and victim of his own moral decay. His sudden death from an apparent heart attack becomes the catalyst for the novel’s central mystery, exposing the rot within medical hierarchies and the ease with which power masks corruption.

Moran’s presence lingers posthumously, his influence felt in the fear, guilt, and suspicion he instilled in those around him.

Cole / Donal Doherty

Initially appearing as a charming, down-to-earth hospital porter, Cole seems to represent warmth, humor, and romantic possibility for Eitan. His easy intimacy offers Eitan respite from judgment and professional anxiety.

However, his eventual unmasking as Donal Doherty — a rejected medical school applicant with a vendetta against Moran, Stein, and Eitan — reframes his character entirely. Donal is a chilling study in resentment and calculated revenge.

His elaborate deception and manipulative brilliance reveal both his intelligence and his capacity for cruelty. By exploiting Eitan’s mental instability and the biases of their professional environment, he orchestrates a perfect frame-up, nearly destroying Eitan’s life.

Donal’s dual identity underscores the novel’s exploration of deceit, class resentment, and the dangers of unchecked ambition. His final confession exposes a system that breeds both privilege and vengeance.

Margaret Corcoran

Margaret Corcoran, Eitan’s colleague and sometime rival, evolves into one of the most layered figures in the narrative. Initially portrayed as a pragmatic, slightly acerbic consultant, she emerges as Eitan’s unlikely ally and moral anchor.

Her complex relationship with Moran — both romantic and professional — exposes her vulnerability and her deep-seated need for respect in a male-dominated workplace. Despite her cynicism, Margaret possesses empathy and courage; her loyalty to Eitan, even in the face of scandal, demonstrates quiet heroism.

Her brush with death and subsequent survival mirror Eitan’s own arc of endurance. In many ways, she represents the voice of reason amid chaos — flawed, human, but ultimately compassionate.

Professor Annabel Stein

Professor Annabel Stein is a commanding yet deeply unstable figure, whose sharp intellect and abrasive leadership conceal fragility. Her descent into manic behavior, exacerbated by cocaine accidentally ingested from Eitan’s spray, parallels Eitan’s own struggle with mental health.

Stein’s character embodies the precarious balance between brilliance and breakdown in high-stakes medicine. Her eventual death, initially perceived as suspicious, contributes to the growing sense of paranoia and conspiracy.

Through Stein, Adam Kay explores the intersection of ego, power, and vulnerability within the medical profession, showing how even the most formidable figures can succumb to psychological collapse.

Davina Hallowell

Davina Hallowell, Moran’s widow, is a woman trapped between rage, humiliation, and grief. Her marriage to Moran was one of mutual deceit — she both despised and depended on him.

Her confrontation with Eitan at the wake, where she publicly accuses him of indecency, reveals her volatility and emotional unraveling. Davina’s actions, though extreme, are driven by the same toxic environment that destroyed her husband — one in which reputation and repression collide.

She stands as a tragic emblem of moral corruption bred by secrecy and status.

Dave Webb

Dave Webb, the hospital pharmacist and Eitan’s drug supplier, operates in the novel’s shadowy underbelly. His casual approach to ethics, blending camaraderie with criminality, highlights the institutional moral decay surrounding Eitan.

Webb’s ambiguous loyalties and manipulation of substances symbolize the blurred lines between healing and harm in both medicine and addiction. Though a minor character, his presence underscores Eitan’s dependence — not just on drugs, but on those who enable his self-destruction.

Suzanne Gillow

Suzanne Gillow, the hospital’s chief executive, represents bureaucratic order amid the novel’s chaos. Though often detached, she embodies the institutional machinery that prioritizes appearances over empathy.

Her decision to suspend and later reinstate Eitan reflects both political calculation and pragmatic compassion. By the end, she stands as a figure of restitution, apologizing to Eitan and acknowledging systemic failure.

Gillow’s character serves as commentary on how institutions weaponize mental health stigma and later feign absolution once the damage is done.

Elodie Rose

Elodie, Eitan’s late sister, haunts the narrative as a symbol of innocence lost and guilt endured. Her death in adolescence — misdiagnosed by Eitan as a hangover — is the emotional core of his trauma.

Through flashbacks and memories, Elodie represents the part of Eitan that remains pure, affectionate, and unjudging. She is the ghost of his better self, reminding him of empathy and love even in his darkest moments.

His final visit to her grave, leaving behind her ring, signifies release and reconciliation.

Themes

Identity and Self-Destruction

Eitan Rose’s journey in A Particularly Nasty Case is an exploration of the fragile line between professional identity and personal implosion. The story presents a man who, once defined by competence and prestige, struggles to reconcile the conflicting versions of himself—a skilled doctor, a grieving brother, a gay man in a conservative field, and an addict battling inner demons.

His self-destructive impulses emerge as attempts to escape guilt and shame rather than as simple moral failings. The novel situates identity as something both performed and concealed, showing how Eitan’s lies about his name, his past, and his mental state reflect his desperation to preserve a socially acceptable version of himself.

His substance abuse, risky encounters, and compulsive need for control illustrate how fragmented identity can drive self-sabotage. Adam Kay uses Eitan’s crisis to critique the medical profession’s hypocrisy: the healer is denied empathy when he becomes the patient.

The pressures of maintaining an immaculate public persona push Eitan further into the chaos he wishes to conceal. By the end, his acceptance of vulnerability—confessing his illness, confronting his guilt over Elodie’s death, and allowing himself to reconnect with life—marks not redemption through triumph but through honesty.

The narrative exposes how identity cannot be built on repression; instead, it must integrate one’s darkest parts. Eitan’s journey from denial to fragile authenticity demonstrates the human cost of living under the suffocating expectations of perfection in both medicine and masculinity.

Guilt and Redemption

Guilt saturates every decision Eitan makes, haunting him like a chronic condition. His sister Elodie’s death is the emotional nucleus of his turmoil, and his misdiagnosis of her illness becomes the wound that never heals.

This guilt metastasizes into his adult life, shaping his relationships, addictions, and his erratic sense of self-worth. In A Particularly Nasty Case, guilt is not only personal but institutional; the medical establishment, obsessed with reputation, offers punishment rather than rehabilitation.

Eitan’s manic attempts to “fix” situations—reviving strangers, exposing supposed murderers, proving his innocence—stem from an unconscious need for atonement. Yet every attempt at redemption leads him deeper into chaos, suggesting that guilt distorts judgment as powerfully as mental illness.

Adam Kay treats guilt as a corrosive yet clarifying force. It compels Eitan to seek meaning in tragedy but also blinds him to proportion and perspective.

The novel reframes redemption not as the erasure of guilt but as its integration. Only when Eitan stops searching for external absolution—when he accepts that Elodie’s death cannot be undone and that his worth is not measured by punishment—does he begin to heal.

His visit to her grave in the final pages is not triumphant but deeply human: an acknowledgment that remorse can coexist with hope. The book suggests that redemption lies in self-forgiveness, not in vindication by others, and that moral recovery requires facing the full mess of one’s past without hiding behind professional or moral pretenses.

Mental Health and Stigma

The portrayal of bipolar disorder in A Particularly Nasty Case is unsparing and empathetic, grounded in the cruel reality of how institutions handle vulnerability. Eitan’s diagnosis is treated as a professional liability rather than a medical condition, exposing the pervasive stigma within healthcare itself.

Colleagues whisper about his instability, superiors weaponize his condition to control him, and the tribunal process frames him as dangerous rather than deserving of support. This systemic coldness mirrors broader societal discomfort with mental illness, particularly in men.

Eitan’s oscillation between mania and despair is rendered not as melodrama but as a distorted form of survival; the manic phases give him the illusion of control and clarity, while the depressive crashes reveal his inner disintegration. The cocaine-laced nasal spray becomes a tragic symbol of self-medication—an attempt to maintain functionality in a world that equates illness with weakness.

Through Eitan, Kay critiques the contradiction of a system that preaches care yet punishes those who need it most. The narrative refuses sentimentality; instead, it portrays mental illness as both isolating and diagnostic of the institution’s own sickness.

By the end, Eitan’s tentative engagement with therapy and a support group for doctors signals a shift from shame to solidarity. His story becomes a quiet manifesto for compassion within medicine—an argument that healing requires understanding, not surveillance.

The theme underscores that madness is not moral failure but the human cost of a system built on denial and perfectionism.

Power, Corruption, and Institutional Decay

Beneath the psychological turmoil of A Particularly Nasty Case lies a biting critique of hierarchical power within hospitals. The medical establishment functions as a microcosm of moral rot: politics, rivalry, and exploitation masquerade as professionalism.

Figures like Dr. Moran and Professor Stein embody this corruption, using authority to manipulate subordinates while hiding their own ethical compromises.

Moran’s cruelty toward Eitan—mocking his mental illness, exploiting his vulnerability—reveals how power in medicine is often exercised through humiliation rather than mentorship. The bureaucratic obsession with image over integrity turns genuine care into performance.

Even after Moran’s death, his influence lingers through fear and gossip, showing how institutional toxicity outlives the individual. Eitan’s investigation into Moran’s and Stein’s deaths exposes the structural decay: falsified reports, silenced complaints, and a culture where truth is less important than control.

Adam Kay’s insider knowledge of hospital politics sharpens this depiction, illustrating that corruption thrives not in overt villainy but in the slow erosion of empathy and accountability. The narrative’s climax, where Eitan is framed for murder, demonstrates how systems protect their own by scapegoating the unstable and the powerless.

Yet, in the novel’s closing acts, small gestures of integrity—Margaret’s defense of Eitan, the Trust’s apology—hint at the possibility of reform. Still, the story leaves readers uneasy, suggesting that institutional healing requires dismantling hierarchies that equate authority with moral superiority.

Truth, Perception, and the Nature of Reality

The novel persistently questions how truth can be known when perception itself is distorted by trauma, drugs, and mental illness. Eitan’s fragmented understanding of events blurs the line between investigation and delusion, creating a psychological mystery as much as a moral one.

In A Particularly Nasty Case, truth operates like a shifting diagnosis—subject to interpretation, bias, and context. The narrative forces readers to experience uncertainty alongside Eitan, making them doubt not only his conclusions but his consciousness itself.

This instability mirrors the medical world’s obsession with certainty; doctors are trained to name and classify, yet Eitan’s reality resists neat categorization. His search for clarity in Moran’s death becomes a metaphor for his need to make sense of his own chaos.

However, every revelation seems to collapse under contradiction until the final confession from Donal Doherty restores external order. Even then, the truth feels fragile, tainted by manipulation and coincidence.

The theme underscores how perception is always mediated by emotion—guilt alters memory, mania amplifies paranoia, and fear distorts reason. By entwining psychological and procedural uncertainty, Kay transforms the medical thriller into a meditation on epistemology: how do we trust what we see when the self is unstable?

The novel concludes not with perfect understanding but with acceptance of ambiguity. Eitan’s peace lies in relinquishing the need for absolute truth, recognizing that perception—like medicine, like life—is a practice of approximation rather than certainty.