Amity by Nathan Harris Summary, Characters and Themes

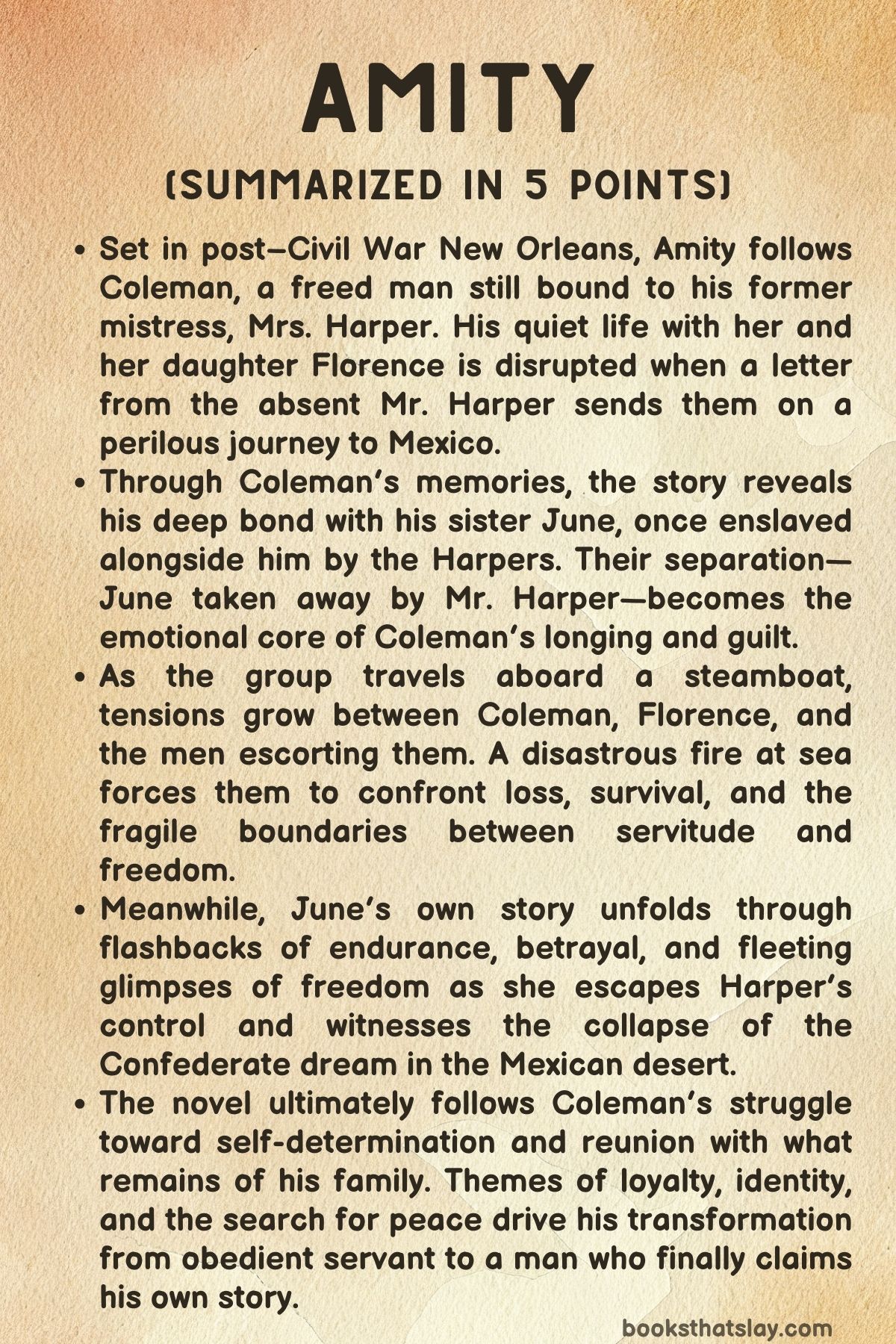

Amity by Nathan Harris is a post–Civil War novel that explores freedom, memory, and the enduring scars of enslavement. Set between Louisiana, Texas, and Mexico in the aftermath of 1865, it follows Coleman, a formerly enslaved man, and his sister June, as they navigate a world reshaped yet still haunted by bondage.

Their journeys—Coleman’s through the chaos of servitude and shipwreck, June’s through exile and survival—intersect across landscapes of loss and redemption. Through their parallel struggles, the story reveals the fragile boundaries between loyalty and liberty, and the resilience required to reclaim one’s humanity from the wreckage of history.

Summary

In the spring of 1866, Coleman lives in New Orleans as a freed man still tethered to the household of his former mistress, Mrs. Harper.

His small pleasures are quiet ones—reading, caring for the terrier Oliver, and keeping peace in a house ruled by the aging woman’s vanity and ailments. When Mrs. Harper sends him to fetch her daughter, Florence, from the park, Coleman obeys reluctantly. Florence refuses to return, voicing her resentment toward her mother and the life of confinement she endures.

Coleman’s attempt to reason with her stirs memories of his past—his sister June, who had been sold alongside him to the Harpers before the war, and the family’s complicated history of favoritism and betrayal.

Years earlier, Mr. Wyatt Harper, desperate after the collapse of his fortune, fled to Mexico with June as his servant, leaving behind his wife, daughter, and Coleman.

Florence’s current disdain toward Coleman echoes the household’s long-buried pain. When Coleman returns home with Florence, they find a stranger, Amos Turlow, visiting Mrs. Harper. He brings news from Mexico—a letter claiming that Mr. Harper wants his family to join him there. Mrs. Harper, thrilled by the idea of reunion, insists they set off immediately.

Coleman, Mrs. Harper, Florence, Oliver, and Turlow board a steamboat named Jubilee.

The journey begins with anticipation, but Coleman feels uneasy about Turlow’s coarse behavior and heavy drinking. One night, Turlow reveals the true purpose of their voyage: Mr. Harper’s letter contains no invitation to his wife or daughter. Instead, Harper commands that Coleman be brought to Mexico to find June, who has escaped him.

Harper demands her return, calling her his “confidante. ” The realization devastates Coleman—his journey is not one of hope, but of manipulation.

The story shifts to June two years earlier, traveling with Wyatt Harper across Texas toward Mexico. Harper’s promise of freedom is hollow; he subjects her to control and exploitation under the guise of affection.

As Confederate exiles chase delusions of new empires, June witnesses their collapse. When violence erupts at the Mexican border, she seizes her chance for freedom, stepping into a world that may finally belong to her.

Back aboard the Jubilee, Mrs. Harper busies herself with a vanity contest on the ship, while Florence sulks and Coleman tends to Oliver.

When fire breaks out in the boiler room, panic consumes the vessel. Amid the chaos, Mrs. Harper refuses to flee without her jewels, and perishes in the flames. Coleman rescues Oliver and helps Florence escape, but Turlow’s behavior during the disaster deepens the mystery surrounding him.

After the wreck, survivors drift into Mexico. Florence, shaken by her mother’s death, clings to Coleman.

Together they seek aid and a way north, still trailed by Turlow. He forces them into his home with his brother Cyrus, where they are held captive.

Using wit and courage, Florence tricks the brothers, injures Cyrus, and escapes with Coleman and Oliver. They find temporary refuge with a guide named William Free, who agrees to lead them through the desert in exchange for Mrs. Harper’s valuables.

Their trek brings new trials—harsh landscapes, hunger, and growing distrust. William proves both pragmatic and philosophical, seeing in Coleman a man divided between servitude and independence.

Together, they encounter Mexican soldiers who imprison them along with the Turlow brothers. In the custody of General Chavez, they witness violence and deceit, but also fleeting humanity.

Coleman’s intelligence earns the General’s respect when he pleads for the return of his dog, Oliver. The General spares him and orders that Coleman accompany him to a mining settlement, where Harper is said to be living.

As the group journeys through the desert, Florence learns that Harper never summoned her. Her bitterness toward Coleman deepens when she realizes he hid the truth.

Their bond—built on shared loss—fractures. A wagon accident kills Turlow and leaves Coleman and Florence wounded.

William saves them, leading them to a border outpost where they meet Celia and Sandy, who tell them Harper’s fate. The man they seek is a mad prospector living in ruin, obsessed with finding silver and haunted by the loss of June.

Coleman, Florence, and William continue into the wasteland, finally reaching Harper’s camp—a miserable tent surrounded by decay. Inside, Harper raves about gold, betrayal, and God.

Florence confronts him for abandoning his family and destroying their lives. She leaves him with her mother’s shoes as a symbol of what he squandered, then departs without forgiveness.

Coleman stays a moment longer, telling Harper that June will never return and that he deserves his solitude.

William prepares to part ways, leaving Coleman with a compass and a horse, urging him to ride toward freedom. Coleman and Florence continue together, but exhaustion and injury threaten to claim them both.

Just as hope fades, strangers appear—Black men and an Indigenous rider who recognize June’s name. They lead Coleman to a settlement called Amity, a haven for the displaced and liberated.

There, amid laughter and light, Coleman finds June. Their reunion is emotional and complete—the siblings embrace, surrounded by the people of Amity, who welcome them as family.

Florence, weakened but alive, witnesses their joy before returning north to Louisiana.

Years later, in Texas, Coleman and June live peacefully in neighboring cabins. June is with Isaac, a man who once helped her escape bondage.

Coleman writes his memories of their journey, filling notebooks with the story of their survival. Oliver, ever faithful, grows old by his side.

One day, Florence sends him his old books from New Orleans—a gesture of reconciliation.

As the sun sets on their quiet homestead, Coleman reads his story aloud to June by the fire. His words recount his passage from servitude to freedom, from silence to voice.

When he begins with the simple phrase, “I had few pleasures to call my own,” June listens, knowing the long road of their suffering has led at last to peace. Through the act of telling his story, Coleman completes his transformation—from servant to author, from witness to survivor—and the legacy of Amity becomes one of endurance, forgiveness, and the human will to reclaim dignity from history’s ashes.

Characters

Coleman

Coleman stands at the emotional and moral center of Amity, embodying the complexity of freedom’s aftermath. Formerly enslaved and now a free man in post–Civil War New Orleans, his existence remains tethered to his former mistress, Mrs.

Harper, in a subtle continuation of servitude. His quiet endurance, dignity, and introspection define his character.

Despite his marginalization, he sustains an inner life through books, memory, and compassion, particularly his attachment to Oliver, the terrier that symbolizes both affection and captivity. Throughout his journey—from domestic servitude to survival through shipwreck and desert—Coleman evolves from a man shaped by obedience to one capable of moral defiance.

His kindness, once mistaken for subservience, transforms into a source of power. In Mexico, under the threat of violence and manipulation, he learns to wield his empathy and intelligence as tools of resistance.

His reunion with June in Amity represents not only familial restoration but also the realization of freedom in its truest sense: the right to one’s own story.

June

June, Coleman’s sister, mirrors his endurance but expresses it through defiance rather than restraint. Her journey from enslavement to self-liberation charts a trajectory of physical and emotional rebellion.

Wyatt Harper’s exploitation of her body and spirit exposes the cruelty of “benevolent” ownership and the hypocrisy of paternalistic masters. Yet, June refuses to let victimhood define her.

She learns to manipulate her oppressors’ delusions to survive, and when chaos erupts during the march to Mexico, she claims her autonomy fully. Her later life with Isaac in Amity shows the possibility of rebuilding after trauma.

June’s wisdom, forged in suffering, radiates in her care for others and in her understanding of freedom as communal, not solitary. She becomes a symbol of survival that transcends violence—an anchor of grace and resistance in the narrative’s moral landscape.

Florence Harper

Florence, Mrs. Harper’s daughter, is one of the novel’s most conflicted figures.

Her upbringing in privilege and emotional neglect produces a restless bitterness that manifests as cruelty toward Coleman. Yet beneath her condescension lies a yearning for connection, suppressed by her social conditioning.

Her evolving relationship with Coleman—from disdain to mutual dependence—reflects her gradual awakening to the illusions of class and race that have imprisoned her. After the shipwreck and her mother’s death, Florence’s survival depends on Coleman’s guidance, reversing their former power dynamic.

Her confrontation with her father in the desert becomes a moment of reckoning: she sees the hollowness of inherited authority and finally claims moral independence. Her later act of sending Coleman his books signifies redemption—a gesture of humility and acknowledgment of shared humanity.

Mrs. Harper

Mrs. Harper embodies the decaying grandeur of the antebellum South, clinging to the remnants of her lost privilege.

Her vanity, self-delusion, and performative fragility mask deep fear and dependence. She is both a victim of patriarchal abandonment and a perpetuator of oppression, unable to see Coleman as anything but property.

Her obsession with appearances—the shoes, the pearls, the “Queen of the Jubilee” contest—reveals the emptiness of her world, one built on domination and denial. Yet Nathan Harris allows moments of sympathy: her loneliness and faith in her husband’s false promises expose her as another casualty of the old order’s collapse.

Her death aboard the Jubilee is both literal and symbolic—the extinguishing of a decaying way of life.

Wyatt Harper

Wyatt Harper personifies the toxic blend of ambition, pride, and moral decay that drives the Confederacy’s ruin. His exploitation of June and betrayal of his family are extensions of a worldview that sees ownership as love and domination as virtue.

His delusions about rebuilding an empire in Mexico reveal the futility of clinging to lost power. By the time Coleman and Florence find him, Harper has become a ghost of his former self—mad, destitute, and consumed by guilt and greed.

His degradation serves as poetic justice: stripped of wealth, respect, and sanity, he confronts the moral emptiness at the heart of his life. Florence’s final act—leaving him with her mother’s shoes—symbolizes a reckoning that words cannot achieve.

Amos Turlow

Amos Turlow is both a villain and a tragic reflection of the violence that shapes men like him. Coarse, brutal, and haunted by his past, Turlow oscillates between cruelty and kinship toward Coleman.

His conversations reveal a twisted admiration—he sees in Coleman a mirror of his own endurance, though one purified by decency. His relationship with power is parasitic: he serves those who exploit him, perpetuating cycles of subjugation.

Yet his flashes of remorse before death suggest the possibility of redemption, however faint. Through Turlow, the novel examines how violence deforms not only its victims but its perpetrators, making him one of Harris’s most psychologically intricate creations.

William Free

William Free emerges as the moral compass of the novel’s later stages. A pragmatic guide hardened by the desert and the wars that scarred his people, he balances cynicism with compassion.

Unlike the Harpers or the Turlows, William sees through the illusions of race and class, valuing action over ideology. His alliance with Coleman and Florence is grounded in mutual respect rather than pity or power.

In his wisdom and practicality, he represents the new order forming in the ruins of the old—one that values survival, honesty, and trust. His final gift of the compass to Coleman is deeply symbolic: it marks not just direction in space but moral orientation, guiding Coleman toward peace and self-definition.

Isaac

Isaac, June’s eventual partner, appears intermittently but leaves a lasting impression as a figure of true liberation. His life among Indigenous communities offers June a vision of coexistence and equality that contrasts sharply with the hierarchies of the world she fled.

Isaac embodies a freedom that is neither violent nor vengeful but rooted in harmony and mutual respect. His compassion allows June to reimagine intimacy beyond servitude.

Together, they build a life of quiet dignity in Amity, serving as a living testament to the possibility of healing after generations of bondage.

Oliver

Oliver, the terrier, functions as more than a pet—he is a living metaphor for affection under captivity. His divided ownership between Mrs.

Harper’s household and Coleman mirrors Coleman’s own condition as a man caught between bondage and freedom. Oliver’s loyalty, innocence, and resilience accompany Coleman through the novel’s most harrowing events, becoming both comfort and conscience.

When Coleman risks his life to save him, it underscores the novel’s central belief: that love, however small, can be an act of rebellion against dehumanization. Oliver’s joyful reunion with Coleman at the end of Amity seals the narrative’s emotional closure, reaffirming hope and continuity after suffering.

Themes

Freedom and Its Complex Boundaries

In Amity, Nathan Harris portrays freedom not as a single moment of emancipation but as a continuum of struggle, negotiation, and personal reckoning. The novel opens in the aftermath of the Civil War, a period when legal freedom for African Americans did not translate into social, psychological, or emotional liberation.

Coleman, though no longer enslaved, continues to live under the shadow of servitude to Mrs. Harper.

His life of “quiet endurance” mirrors the condition of countless freedmen who found themselves trapped between the old world of bondage and the elusive promise of self-determination. Freedom in this narrative becomes a haunting paradox—an ideal that is both yearned for and feared.

Coleman’s education, refinement, and restraint signify his attempt to claim dignity through intellect, yet society and circumstance continually remind him of invisible chains. June, on the other hand, embodies a more radical pursuit of liberation.

Her journey through the Mexican frontier, amid chaos and ruin, becomes a physical and moral odyssey toward reclaiming agency over her body and destiny. Her rejection of Wyatt Harper’s domination and her final settlement in Amity mark the true birth of freedom—one grounded in self-possession rather than external validation.

The novel challenges the conventional notion that emancipation ended slavery; instead, it presents freedom as an unfinished and deeply personal journey. By contrasting Coleman’s cautious endurance with June’s defiant transformation, Harris exposes how liberation must be both internal and collective to be complete.

Memory, Trauma, and the Burden of the Past

Memory serves as both a source of identity and a weight that Coleman and June must bear throughout Amity. The novel is structured as an act of remembrance—Coleman’s eventual decision to write his story suggests a desperate need to order chaos through narrative.

Yet memory, in this world, is not merely recollection but re-experience; it refuses to fade. Coleman’s flashbacks to his and June’s enslavement, their separation, and the indignities endured under Wyatt Harper’s rule reveal how trauma shapes perception long after physical escape.

The psychological scars of bondage manifest in Coleman’s hesitation, his compulsive politeness, and his uneasy relationship with Florence and Mrs. Harper.

For June, memory becomes both torment and compass. Her recollections of Wyatt’s exploitation fuel her will to survive and later, her ability to build a community free from subjugation.

However, memory is not only personal—it infects the descendants of the oppressors as well. Florence’s bitterness and Mrs.

Harper’s delusions show the corrosive power of inherited guilt and denial. By intertwining the recollections of the formerly enslaved and their former masters, Harris constructs a portrait of a society that cannot heal because it refuses to confront its collective past.

In the closing scenes, when Coleman finally reads his written account aloud to June, memory becomes redemption—a means of reclaiming narrative ownership and transforming pain into testimony.

The Persistence of Power and Subjugation

Throughout Amity, power operates not only through overt violence but through subtler dynamics of dependency, manipulation, and psychological control. Mrs.

Harper’s relationship with Coleman epitomizes the persistence of old hierarchies under the guise of affection and civility. Her command over him, framed as domestic loyalty, reveals how social systems of dominance can reconstitute themselves even after their formal collapse.

Turlow’s cruelty and Wyatt Harper’s obsessive authority over June extend this idea, exposing masculinity as a corrupting force that sustains itself through domination. Yet Harris complicates this view by depicting the enslaved as participants in nuanced power exchanges.

Coleman’s politeness becomes a survival strategy that occasionally grants him moral authority, while June’s quiet defiance under Harper’s tyranny grows into true strength. In the Mexican chapters, power shifts dramatically—the white Southerners lose control amid the desert chaos, and Coleman must navigate a new political landscape under General Chavez.

But even there, freedom remains conditional; Coleman’s intelligence and integrity are still measured against white expectations. By the novel’s end, Harris suggests that power can be resisted but not easily erased.

The structures of subjugation mutate across borders, classes, and identities, demanding constant vigilance from those seeking autonomy.

Brotherhood, Family, and the Search for Belonging

At the heart of Amity lies the yearning for connection in a world fractured by loss and betrayal. Coleman’s devotion to his sister June drives the entire narrative; his journey is as much a search for her as for himself.

Their eventual reunion, tender and cathartic, redeems years of displacement and silence. Harris uses the siblings’ bond to explore how kinship becomes a sanctuary against dehumanization.

Yet family, in this novel, is not limited by blood. Florence, despite her privilege and cruelty, becomes an unlikely companion to Coleman in exile, their shared suffering forging a fragile empathy.

Similarly, June finds solidarity with Isaac and others who help her imagine a future beyond servitude. In contrast, the Harper family disintegrates under the weight of selfishness and deceit, illustrating how oppressive systems corrode even the intimate ties of love and loyalty.

The creation of Amity—a community of freedpeople and outcasts living in harmony—embodies the novel’s vision of chosen kinship. In this new social order, belonging arises from mutual recognition rather than hierarchy.

Coleman’s declaration of happiness in Amity closes the circle: he has at last found a home where affection and equality coexist, where family is built through shared endurance rather than imposed bonds.

Healing Through Storytelling and Self-Expression

Storytelling becomes both the structure and the salvation of Amity. From the beginning, Coleman’s love of reading sets him apart, granting him an interior life denied to most enslaved people.

His eventual act of writing transforms passive suffering into active creation—a defiant assertion that his life, once controlled by others, now belongs to his own voice. Harris uses Coleman’s authorship as a metaphor for historical reclamation: the written word becomes the means by which the silenced bear witness to their truth.

June’s survival and her later peace with Isaac mirror this healing through expression, not necessarily through writing but through living authentically in the community they help build. The novel suggests that storytelling bridges the chasm between memory and renewal.

By narrating his past, Coleman ensures that the pain he and others endured will not be lost to time or consumed by the lies of their oppressors. In the closing scene—Coleman reading his life story to June beside the fire—speech itself becomes an act of liberation.

What was once endured in silence is now spoken, what was hidden becomes shared. Through the power of narrative, both siblings finally transcend their trauma, turning suffering into meaning and history into hope.