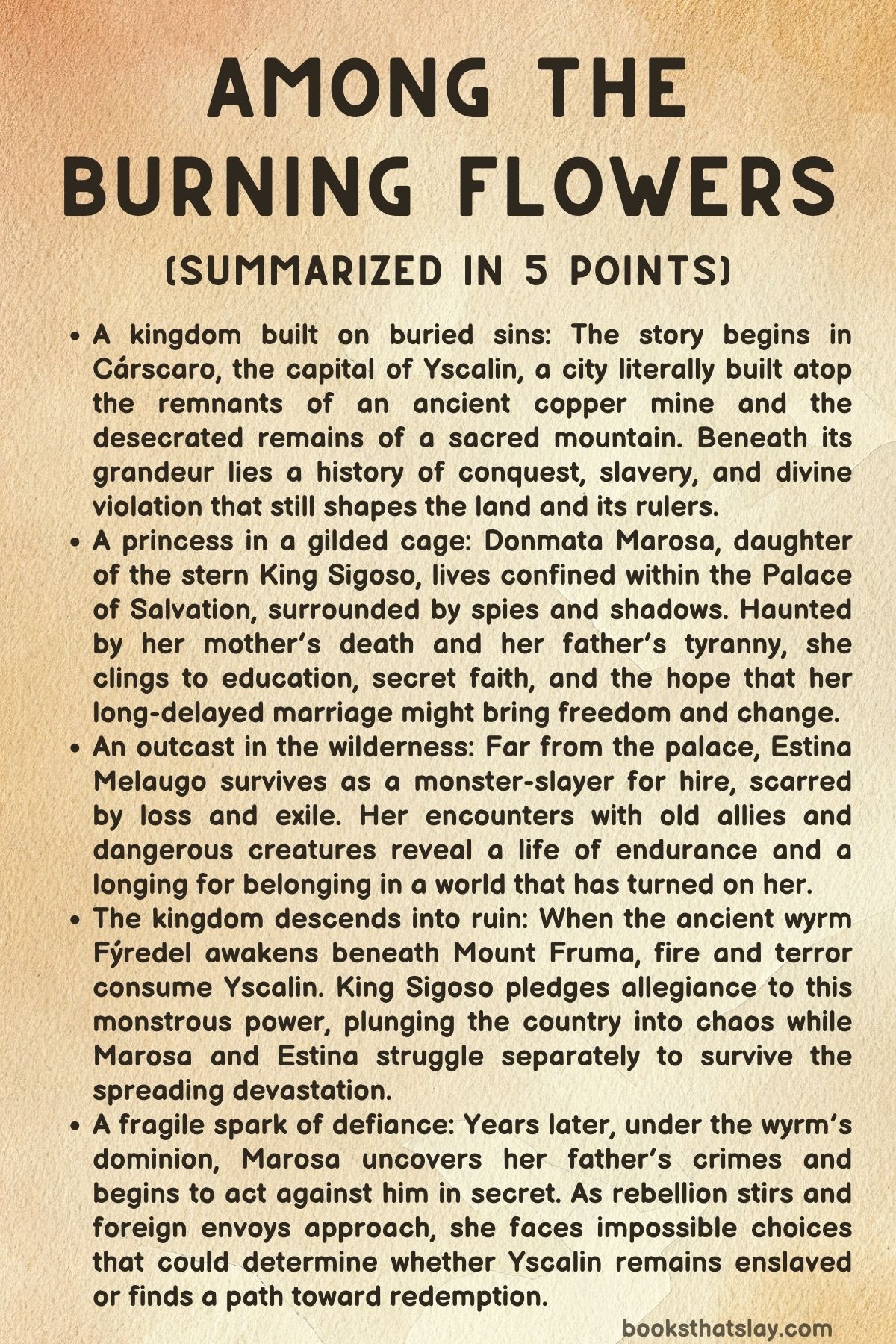

Among The Burning Flowers Summary, Characters and Themes

Among The Burning Flowers by Samantha Shannon is a sprawling epic of faith, rebellion, and survival set in the shattered kingdom of Yscalin. The novel follows two women—Princess Donmata Marosa, a captive royal struggling under her tyrannical father and the rise of an ancient wyrm, and Estina Melaugo, an outlawed slayer of beasts haunted by loss.

Their lives, shaped by oppression and fire, move toward an inevitable reckoning as monstrous forces awaken beneath their land. Shannon blends political intrigue, personal sacrifice, and the burden of legacy into a dark fantasy that explores the endurance of hope in a world consumed by ruin.

Summary

The story begins in Cárscaro, the capital of Yscalin—a city built atop a desecrated mountain once mined for copper by conquerors who enslaved the native Yscals. Centuries later, the city has become a furnace of molten canals and blackstone towers.

Princess Marosa, daughter of King Sigoso, lives confined in the Palace of Salvation, a fortress built by past queens to symbolize strength. Though surrounded by grandeur, Marosa is isolated and under constant surveillance.

Her father forbids her from attending council or engaging in governance, keeping her as an ornament of obedience. Her only comforts are her cousin Priessa, her loyal guard Ermendo, and a few trusted friends.

Beneath the surface of royal splendor lies suffocating despair. Marosa mourns her mother, Queen Sahar, who died mysteriously after a failed attempt to flee the palace.

Haunted by guilt and confinement, Marosa finds solace in secret acts of defiance—studying politics and history, and corresponding with Queen Sabran of Inys, her ally and friend. Her hope for freedom rests on her long-delayed marriage to Prince Aubrecht of Mentendon, a union she believes will grant her purpose and autonomy.

But her father delays the match endlessly, determined to keep her within his grasp.

While Marosa endures her golden cage, far to the south, Estina Melaugo struggles to survive as a wandering culler of Draconic beasts. Branded a criminal and living by her blade, Estina hunts wyverns and lindworms in exchange for food or coin.

Her past is marked by tragedy—once a vineyard girl, she lost her family to famine and became a thief, then a monster-slayer. Her only close bond is with Liyat, a smuggler and former lover.

When Captain Harlowe offers Estina a place aboard his ship, she refuses, unwilling to abandon Yscalin or Liyat despite the dangers. But as wyverns return and terror spreads, Estina begins to question whether her homeland is worth dying for.

Back in Cárscaro, Marosa’s world begins to tremble—literally. Frequent earthquakes shake the palace, culminating in a catastrophic eruption from Mount Fruma.

From its fiery depths emerge wyverns not seen for centuries, heralding the return of Fýredel, the Iron King, an ancient wyrm who once waged war against humankind. The sky darkens, the air fills with ash, and chaos spreads across Yscalin.

When Fýredel demands the presence of the King, Sigoso first sends a decoy to meet the beast. The decoy is burned alive before the city’s eyes.

Finally confronting the wyrm himself, Sigoso returns changed—his eyes ashen, his faith broken. He proclaims allegiance to the Nameless One and denounces the Saint’s Church, plunging Yscalin into a new dark age.

Across the kingdom, panic erupts as towns burn and citizens flee. Estina and Liyat attempt to escape through the city of Ortégardes, but wyverns descend upon the populace.

Fleeing through sewers and burning streets, they witness the fall of civilization. Pursued by fire, they reach Oryzon, where they finally accept passage on Harlowe’s ship, the Rose Eternal, and sail away as Yscalin collapses into ruin.

Two years later, Cárscaro lies under Draconic occupation. Fýredel’s wyverns patrol the skies, and King Sigoso, infected by the plague of the wyrms, serves as a hollow puppet.

The population starves, and rebellion is brutally crushed. Princess Marosa, now effectively ruler in her father’s stead, secretly aids her people—smuggling medicine, hiding loyalists, and seeking allies.

The court has become a nest of spies and cultists devoted to Fýredel. In this atmosphere of terror, Lord Wilstan Fynch, the Inysh ambassador, confides in Marosa that Sigoso once murdered Queen Rosarian of Inys, a crime long concealed.

Searching the sealed Privy Sanctuary, Marosa finds proof—a poisoned gown and cryptic letters revealing her father’s guilt. The revelation shatters her loyalty and confirms her mother’s suspicions, for which Sahar had died.

Determined to redeem her family’s name, Marosa vows to survive and expose the truth. Yet Fýredel’s influence deepens, and Yscalin becomes a kingdom of plague and worshippers of the wyrm.

In Mentendon, Prince Aubrecht struggles to rescue her but faces impossible odds. After repeated failures, political pressure forces him to annul their betrothal and marry Queen Sabran instead, uniting their nations against the growing Draconic threat.

Marosa, hearing of this, suppresses her heartbreak and devotes herself to her people’s survival.

Fýredel soon summons Marosa, commanding her to act as his proxy ruler and execute a prisoner named Jondu. When Marosa meets the captive, she learns that Jondu is a messenger from the Ersyr, her mother’s homeland, carrying a secret weapon that could destroy the wyrms.

Jondu reveals the existence of a tunnel beneath the palace leading through the mountains to the Ersyri border. Moved by pity, Marosa spares her and helps her attempt escape using basilisk venom to melt the bars.

Jondu dies fighting, but her message takes root in Marosa’s heart.

Sigoso retaliates savagely, executing Marosa’s allies and displaying their bodies in public. Yet rebellion grows in secret.

Marosa entrusts the Ersyri box Jondu carried to Wilstan Fynch, instructing him to deliver it to Ambassador Chassar uq-Ispad in the Ersyr. Fynch agrees and escapes through the tunnel, vowing to infect himself with the Draconic plague so he can pass safely through the wyrm-infested lands.

When Marosa later follows the path, she finds his corpse mutilated and the box abandoned. Retrieving it, she realizes that even her most loyal friends cannot withstand the darkness spreading across the continent.

Returning to Cárscaro, Marosa hides the box and continues her resistance. She writes secretly to Queen Sabran, warning that Yscalin still lives and that Fýredel’s forces are gathering.

Her last hopes rest on the arrival of Inysh envoys. As Fýredel prepares to launch an assault on Inys itself, Marosa steels herself for her final deception.

She dons the iron helm meant to mark her as Fýredel’s voice, disguising her rebellion beneath the guise of submission. When the envoys Arteloth Beck and Kitston Glade arrive, she sits upon the obsidian throne as the apparent ruler of Yscalin.

Beneath her mask, she plans to entrust them with the box—a fragile seed of salvation in a world devoured by flame.

Among The Burning Flowers ends on this note of defiant endurance. Through Marosa’s courage and Estina’s survival, Shannon leaves readers poised on the edge of a rekindled war between light and darkness, faith and tyranny.

The novel becomes not merely a tale of destruction, but a testament to the will to resist—even when all that remains burns.

Characters

Donmata Marosa

Donmata Marosa, the daughter of King Sigoso and heir to the throne of Yscalin, stands as the emotional and moral center of Among The Burning Flowers. Her journey begins in confinement, a princess surrounded by grandeur but imprisoned by her father’s will.

The oppressive palace walls and the ever-glowing lava canals of Cárscaro mirror her suffocating existence, transforming her gilded life into a symbol of endurance and restraint. Haunted by her mother Queen Sahar’s tragic death, Marosa carries the weight of generational trauma and the burden of unfulfilled destiny.

Her suppressed yearning for freedom manifests not only in her intellectual pursuits—studying history, politics, and faith in secrecy—but also in her silent defiance against her father’s tyranny. As the kingdom falls into ruin and Fýredel’s terror spreads, Marosa’s resilience deepens.

She evolves from a sheltered princess into a quiet revolutionary, embodying both compassion and cunning. Her choice to preserve Jondu’s dignity and her alliance with Wilstan Fynch mark her transformation into a sovereign figure driven by justice and legacy.

In the end, Marosa’s endurance amid despair reflects the novel’s central meditation on faith, inheritance, and the flame of hope that survives even among the ashes of tyranny.

King Sigoso

King Sigoso, ruler of Yscalin and father to Marosa, embodies the corruption of power and the tragic decay of the human spirit. Once a proud monarch, his reign becomes a slow descent into madness and moral disfigurement.

His relationship with Marosa oscillates between authoritarian control and emotional manipulation, making him both patriarch and oppressor. Sigoso’s allegiance to the Nameless One—sealed by his submission to the wyrm Fýredel—marks his complete surrender to darkness.

Yet his sins stretch far beyond faithlessness; his murder of Queen Rosarian and his betrayal of Marosa’s mother, Sahar, reveal a man driven by wounded pride and an insatiable thirst for dominion. The physical corruption he endures under Fýredel’s influence—his eyes turned to ash and his flesh blistered—serves as a grotesque mirror of his moral decay.

Ultimately, Sigoso becomes less a man than a vessel, his humanity consumed by the very forces he sought to command. Through him, the novel interrogates the nature of patriarchal power, guilt, and the self-inflicted ruin of kingship.

Estina Melaugo

Estina Melaugo’s story unfolds in stark contrast to Marosa’s: where Marosa is caged by luxury, Estina is bound by poverty and exile. A hunter of draconic beasts, Estina’s life is one of relentless survival, marked by scars both physical and emotional.

Orphaned, impoverished, and branded an outlaw, she transforms her suffering into strength, using her defiance as a weapon against the world that rejected her. Her encounters with Captain Harlowe and her complex love for Liyat expose her buried vulnerability beneath her hardened exterior.

Estina’s moral code, shaped by necessity, aligns her with the archetype of the reluctant hero—a woman who kills to live yet dreams of tenderness and belonging. When the world collapses into chaos, Estina’s endurance parallels Marosa’s; both women become symbols of resistance against destruction.

Her eventual flight aboard the Rose Eternal is not an escape but a reluctant surrender to survival, leaving behind a homeland she both despises and loves. Through Estina, the novel gives voice to the forgotten—the marginalized who endure even when kingdoms fall.

Liyat

Liyat serves as both moral anchor and emotional counterpart to Estina. A woman of intellect and idealism, she represents the pull of conscience in a world that rewards cruelty.

Her relationship with Estina—rooted in shared hardship, smuggling, and forbidden affection—illustrates the tension between love and survival. Liyat’s compassion contrasts with Estina’s pragmatism; where Estina kills to live, Liyat dreams of rebuilding and healing.

Her insistence that Estina flee Yscalin reveals both her foresight and her deep understanding of how societies punish difference. Yet her affection carries traces of frustration and sorrow, as she grapples with Estina’s stubbornness and self-destruction.

Liyat’s strength lies not in battle but in endurance of another kind—the courage to love a broken person in a broken world. Through her, the narrative explores themes of redemption, intimacy, and the cost of hope amid ruin.

Queen Sahar

Queen Sahar, though long dead when the story begins, casts a profound shadow over Marosa’s life and over the entire kingdom. Once a queen of grace and quiet rebellion, she embodies the spirit of moral resistance against tyranny.

Her adherence to the outlawed faith of Dwyn and her dream of a tolerant Yscalin make her both visionary and martyr. Sahar’s failed escape attempt and her murder at Sigoso’s hands cement her as a tragic figure—a woman silenced for daring to live by compassion rather than conquest.

To Marosa, Sahar becomes an almost sacred memory, a symbol of what could have been—a mother’s love entwined with moral courage. Her presence lingers through relics and memories, guiding Marosa’s actions long after her death.

Through Sahar, Among The Burning Flowers explores the inheritance of faith, the persistence of memory, and the idea that true queenship is measured not in rule but in mercy.

Lord Wilstan Fynch

Lord Wilstan Fynch, the Inysh ambassador and father to Queen Sabran, emerges as one of the most complex supporting figures. Diplomat, father, and man of conscience, Fynch embodies the fragile thread of human decency amid political and supernatural chaos.

His interactions with Marosa are marked by a paternal gentleness that stands in contrast to her father’s cruelty. His discovery of Sigoso’s crimes and his eventual self-sacrifice reveal both his bravery and his tragic idealism.

Fynch’s death, brutal and senseless, underscores the cost of truth in a world ruled by deceit and monsters. His role bridges nations and generations, serving as the moral witness to the collapse of Yscalin’s humanity.

Through him, the novel underscores the fragility of alliances and the enduring power of integrity even in the shadow of annihilation.

Fýredel, the Iron King

Fýredel, the resurrected High Western wyrm, embodies the elemental force of destruction and spiritual corruption. Unlike mere monsters of legend, Fýredel represents the return of humanity’s deepest sins—greed, pride, and the hunger for dominion.

His voice, resonant through King Sigoso’s decaying body, becomes the haunting echo of absolute power. Fýredel is both god and parasite, devouring faiths and twisting them into worship of ruin.

His enslavement of Cárscaro and his manipulation of Sigoso transform the wyrm into an allegory of tyranny unbound by mortality. Yet his fascination with Marosa adds a chilling psychological layer: he sees in her the potential for rebellion and corruption alike.

Fýredel’s presence marks the boundary between myth and reality, making him the apocalyptic heart of Among The Burning Flowers, where faith itself burns under the weight of his shadow.

Priessa

Priessa, Marosa’s cousin and handmaiden, provides the emotional warmth and human grounding that Marosa so desperately needs. Her loyalty is unwavering, yet she is no mere servant; Priessa is both confidante and co-conspirator, offering courage in quiet acts of rebellion.

She represents the quiet, feminine strength that persists beneath oppression—the power of companionship and survival through empathy. While the world outside burns, Priessa remains Marosa’s link to humanity, reminding her of love and laughter even amid ruin.

Her counsel to feign loyalty and her subtle aid in Marosa’s secret plans show her pragmatic intelligence. Through Priessa, the novel celebrates solidarity among women as both shield and weapon against patriarchal and supernatural tyranny.

Themes

Conquest, Extraction, and the Wounded Landscape

Cárscaro stands as a monument to conquest, literally built atop the mined-out corpse of Mount Fruma, and the city’s geology becomes a ledger of historical violence. The Gulthaganian defilement of a petrified god for copper inaugurates the novel’s meditation on how empires convert sacred ground into commodity, and how places remember what was taken from them.

Long after the invaders are driven out, their logic persists: tunnels, blackstone, and canals that redirect lava show a ruling class determined to command nature rather than repair it. The capital’s constant tremors and the river of fire—the Tundana—turn the city into a furnace that both preserves and condemns its inhabitants, a punitive climate engineered by power.

That decision produces a moral temperature as well: the heat is the pressure under which lies and betrayals are annealed. In Among The Burning Flowers, extraction is never only mineral; it is spiritual and cultural.

The Yscali memory of a god-turned-ore echoes with the erasure of faiths, while the later Gulthagan-style temple resurrected by Fýredel’s cult shows how architecture becomes a second conquest, overwriting devotion with spectacle. Even the city’s light is stolen light—molten, coercive, and surveilling—erasing the privacy of night.

Against this backdrop, personal choices gain geological resonance: every secret passage, every sealed sanctuary, and every concealed relic becomes a counter-mine, a human burrow dug to retrieve a buried truth. The land, once desecrated, answers with eruptions and wyrms; the past refuses to stay buried when it has been quarried for profit.

Empire leaves slag heaps in the soul as well as in the earth, and the story insists that reform must address both strata or the ground will keep breaking open beneath the living.

Captivity, Patriarchal Control, and the Struggle for Agency

Marosa’s life is a case study in how authority confines under the pretense of protection. The Palace of Salvation’s blackstone bulk is advertised as strength, yet for the princess it functions as restraints carved into stone.

Surveillance replaces family, routine substitutes for education, and the accusation of “treasonous ambition” polices even the desire to learn. Sigoso controls movement, marriage, public discourse, and even the memory of the dead, turning kinship into garrison.

The cruelty is administrative as much as overt: meals alone, curated hours, barred council rooms, and the slow erosion of self-trust contribute to a carceral atmosphere that needs no visible shackles. The iron helm prepared for Marosa expands this logic by conscripting her very face into tyranny, drafting her body as a proxy for the wyrm’s will.

In Among The Burning Flowers, agency survives as practice rather than declaration—secret lessons, coded inquiries, smuggled weapons, and a private archive beneath the floor tile. The narrative refuses to romanticize endurance; it shows the cost of persistence in the bodies of handmaids, guards, and friends hung at the Gate of Niunda.

Yet it also shows the precision of resistance. Mercy to Jondu is not softness but strategy; theft of the iron box is a choice to bear danger rather than transmit it to others.

The contrast with Estina’s outlaw freedom—mobile but precarious—underscores the spectrum of female agency under patriarchal regimes: one woman fights for room to act within the palace’s labyrinth, the other bargains for breath in the woods and ports. Both are punished for initiative; both persist anyway, revealing that agency in such conditions is the art of extracting a future from rooms designed to hold only the present.

Faith, Heresy, and the Politics of Belief

Public religion in Yscalin is a theater of legitimacy, and belief becomes a currency that rulers spend to buy obedience. Sigoso’s conversion to the Nameless One is less a revelation than a coup staged through doctrine; he rebrands capitulation as truth and desecration as enlightenment.

Earlier, the Saint’s Church had already outlawed the mirror creed of Dwyn, proving that orthodoxy is enforced from multiple directions and that persecution tends to be portable across regimes. Marosa’s hidden necklace, the mirror of compassion, reframes faith as self-knowledge rather than weapon, and the contrast is telling: one creed demands public performance at plazas; the other asks for private integrity in a locked chamber.

In Among The Burning Flowers, heresies are defined by whoever holds the balcony, but conscience persists at ground level. The book treats creeds not as static, but as tactical: letters in cipher, sanctuaries razed and rebuilt, conversions announced by released doves that never return.

The wyverns’ new temple and the substitution of Gulthagan aesthetics show how theology is inseparable from cultural domination; to change the god, the regime also changes the shape of the city. Yet faith remains a resource for resistance when it anchors ethical action rather than state narrative.

Marosa’s prayers do not absolve her of choices; they sharpen them. Jondu’s plea and the red-dyed cloak suggest a parallel, older sacrament rooted in sacrifice and oath, outside sanctioned liturgies.

The novel therefore turns doctrinal conflict into a question of what kind of world belief builds. If creed justifies cruelty, it is idolatry of power; if creed protects the vulnerable, it becomes a discipline of remembering the image in the mirror.

Monsters, Plague, and the Return of the Suppressed

Wyrms, wyverns, and the Draconic plague are not mere antagonists; they materialize what authority has tried to repress: stolen gods, buried mines, concealed murders, and a nation taught to forget. The timing is pointed—the Dreadmount opens after years of engineered denial, and the Iron King speaks through a ruler whose body is rotting from a new variant of contagion.

The plague that greys the eyes and blisters the flesh parallels moral infection: lies carried by the throne enter the bloodstream of the state. In Among The Burning Flowers, monstrosity is communicable because cruelty is.

The creatures that darken the skies enforce external conquest, but they also dramatize internal collapse, exposing how quickly a hierarchy that feeds on fear will collaborate with anything that promises more fear to wield. Estina’s profession as culler demonstrates another angle: communities outsource violence to specialists, then scapegoat them for the violence’s stain.

She bears literal scars for work that allows villages to sleep, yet she is branded unfit for the very society she protects. Meanwhile, the plague functions both as ward and threat; to cross the mountains, one must carry it, and to be cured requires trust in an uncertain remedy.

That paradox—sickness as passport—captures the book’s conviction that survival sometimes requires bearing witness to what harms, rather than masking it. The result is a world where monsters challenge humans to answer what they have become.

If the wyrm commands obedience and men comply with zeal, the category of monster grows uncomfortably wide. The question ceases to be who is human and becomes who is still accountable to the living.

Truth, Memory, and the Control of Narrative

The sealed Privy Sanctuary offers an anatomy of power’s relationship to truth: a mutilated portrait, ciphered letters, and a vial of basilisk venom that rewrites an assassination from rumor to evidence. Sigoso depends on narrative management—accusing his daughter of ambition, isolating her from council, and converting apostasy into revelation.

His regime demonstrates that lies require architecture: galleries to display curated images, gates to display curated corpses, and emissaries to export curated messages. In Among The Burning Flowers, investigation is counter-architecture.

Marosa’s research skills, bolstered by hidden study in politics and history, make discovery possible when formal institutions have been corrupted. The book therefore treats archives as battlegrounds where futures are negotiated.

When Fynch confesses his own fatal letter, the scene underscores how even partial truths can mislead allies and foreclose aid. The story refuses consolations: evidence does not guarantee protection, and confession from a diseased king does not immediately free a city.

Yet truth changes the horizon; it clears the fog around loyalty and equips Marosa to make alliances without self-deception. Memory operates the same way at the personal level.

The miniature of Sahar and the mirror of Dwyn are not keepsakes; they regulate judgment in the present, extracting a living ethic from the dead. The iron box destined for Chassar extends this logic: an object that carries the possibility of a different narrative for the whole world, if only it can be delivered.

The contest is therefore not simply over swords or spells but over who will author the account that coming generations inherit, and whether that account will free or chain them.

Love, Loyalty, and the Cost of Keeping Vows

Promises in this story are tested under ash and iron. Marosa’s betrothal to Aubrecht begins as a pathway to freedom and reform, then hardens into heartbreak as political pressures annul it.

The posy ring with its hopeful inscription survives the collapse of letters and missions, passing from finger to pouch to the snow beside Fynch’s body before returning to Marosa’s hand. That small circle becomes a measure of the distance between intention and history.

In Among The Burning Flowers, vows are not sentiment but strategy and burden. Estina and Liyat’s bond, born in illicit work and sharpened by scarcity, refuses neat romance; it is affectionate, exasperated, practical, and often at cross-purposes.

Liyat urges flight; Estina clings to homeland. Their love demands choices about risk, allegiance, and the meaning of home, and the sea voyage on the Rose Eternal converts intimacy into logistics—signals, lifeboats, and the willingness to be pulled aboard a future one did not plan.

Loyalty to friends can also be fatal. Ermendo’s corpse and Yscabel’s torment make clear that the enemy understands attachment as leverage, and the Gate of Niunda becomes a scoreboard where fidelity is punished in public.

The novel asks whether love can be both shield and spear: a force that protects dignity while advancing action. Marosa’s mercy to Jondu, Ruzio’s escape with Bartian, and Fynch’s decision to carry the box all count as forms of keeping faith that cost blood.

Even Aubrecht’s annulment reads not as betrayal but as a confession of limits, a painful admission that love without access cannot rescue. The story answers with a hard hope: vows can be kept in new forms, redirected to the living task of protecting a people who may never know the names of those who stood for them.

Diplomacy, Betrayal, and the Machinery of Power

Embassies, councils, and treaties appear as fragile bridges extended over chasms of pride and injury. Fynch arrives with titles and experience, yet cannot secure an audience with a king who prefers control to conversation; later he risks everything on a courier mission that official channels cannot accomplish.

In Among The Burning Flowers, diplomacy succeeds only when participants accept personal risk and tell unfashionable truths. The larger stage is merciless.

Sigoso’s court uses proxies—Orentico dressed as a decoy king—to game the optics of courage, revealing a cabinet that believes survival is a problem of presentation. The wyrm’s manipulation of Sigoso weaponizes that cynicism, turning the monarch into a megaphone whose words are backed by fire rather than trust.

Mentendon’s council, faced with repeated failures to reach Cárscaro, pressures Aubrecht to cut ties, demonstrating that prudent statecraft and moral solidarity often diverge. Meanwhile, cities like Ortégardes and Oryzon illustrate the limits of etiquette and commerce when air fills with ash; their gates, plazas, and ports buckle under forces that do not negotiate.

Yet the novel refuses defeatism. Diplomacy shifts scale: a princess writes letters in secret; a handmaid brokers first contact with new envoys; a masked audience becomes the only available theater for truth.

The iron box again becomes a diplomatic instrument—a compact without words that, if delivered, could reconfigure alliances. Betrayal is therefore not only personal but procedural: when institutions refuse their purpose, individuals must improvise new ones.

Power persists as motion—the ability to move people, messages, and meanings across distances—and every blockade produces a counter-route, whether through storm drains, lava tunnels, or the open sea.

Hope, Resilience, and the Ethics of Mercy under Catastrophe

Fire-dimmed skies, ash-choked streets, and public executions create conditions in which hope might appear foolish, yet the book frames hope as practiced skill rather than mood. Marosa inventories supplies, sews protective cloths, studies governance, and composes letters that could outlive her; these acts are scaffolding for a future no one else is building.

In Among The Burning Flowers, resilience is an economy of attention: careful listening to rumors from the plains, private prayers that steady the hand before decisive theft, and the quiet courage to bathe after witnessing horror, reclaiming a fragment of normalcy. Mercy appears again and again as an ethical wager that something better can still be made.

Granting Jondu a chance to die fighting rather than as spectacle asserts the non-negotiable dignity of the condemned, even if the practical outcome is the same. Estina’s grit in poverty, her readiness to be mocked for taking the culler’s trade, and her finally saying yes to the Rose Eternal express a hope that does not wait for ideal conditions.

The narrative sets against despair small counter-signs: a foreign bird over the terrace, a serin returning to the city, a posy ring recovered from the snow. These are not sentimental decorations; they are permission slips for the imagination, proof that the world still contains unsupervised beauty and recoverable promises.

The book argues that mercy is not naïve in catastrophe; it is the only politics that survives it with a human face. When Fýredel launches to strike new lands, the story narrows in on preparation, not panic.

Resilience is revealed as the discipline of getting the right object to the right hands at the right time, so that when the mountain speaks again, someone is ready to answer.

Identity, Exile, and the Meaning of Home

Home in this story is a contested verb. For Marosa, the palace is both birthplace and prison; for Estina, the forest and the port are alternately refuge and threat.

Loyalty to place keeps both women in danger, yet leaving does not equal freedom—ships can be besieged, foreign cities can burn, and salt water cannot wash away a bounty on one’s name. In Among The Burning Flowers, identity is shaped by what one protects when escape is possible.

Estina’s refusal to abandon Yscalin until the last possible moment is pride, grief, and love braided into a single stance; her eventual departure with Liyat is not surrender but a recalibration of where she can stand and still be herself. Marosa’s repeated returns to hidden rooms and tunnels demonstrate the opposite trajectory: she will not flee until the task is set in motion, and even then she intends to circle back.

Exile thus becomes liminal action rather than destination. The book treats names—Donmata, culler, ambassador, afleytan—as passports stamped by other people; the bearer must continually decide whether to present them or forge new ones.

The tunnel under Cárscaro, reaching toward the Ersyr, literalizes a thesis about belonging: sometimes the only way to remain true to one’s country is to leave it long enough to bring back what it needs. Home is not the walls but the work.

When the final audience convenes and Marosa sits masked upon the obsidian throne, she is at once most foreign to her city and most loyal to it, carrying an unnamed hope behind a helm designed to erase her. The novel suggests that true belonging is earned by the decisions that keep a people possible, even if those decisions are made in borrowed rooms and under false light.