Cold Island Summary, Characters and Themes

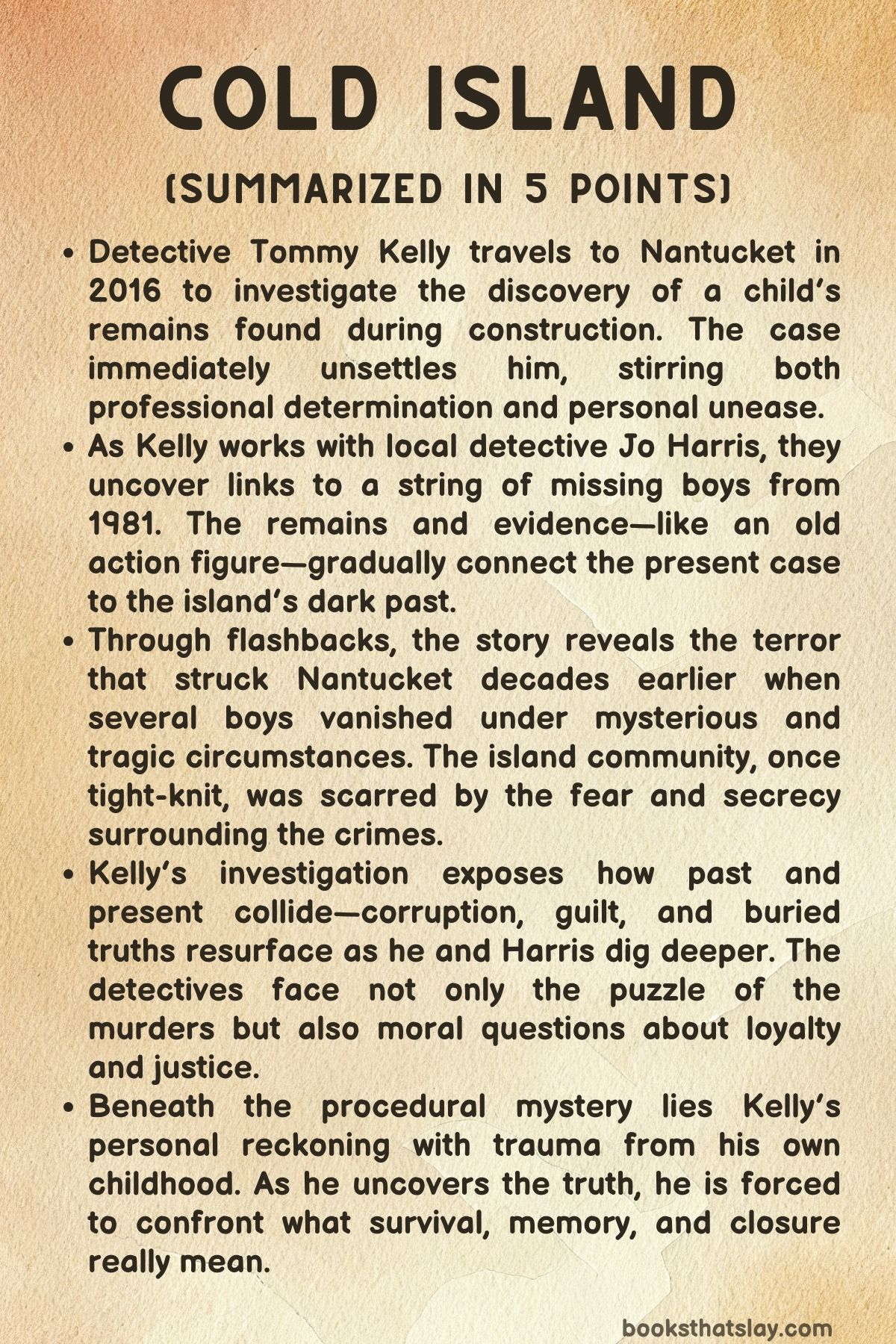

Peter Colt’s Cold Island is a crime novel that spans decades, connecting the unsolved horrors of 1981 Nantucket with the investigations of 2016. Through the eyes of State Police Detective Tommy Kelly, the story explores memory, guilt, and the hidden rot beneath a picturesque island’s surface.

When a child’s remains are unearthed during modern construction, old wounds reopen—forcing Kelly to confront buried secrets, both the town’s and his own. Colt blends police procedural precision with human fallibility, tracing how silence, corruption, and trauma ripple through generations long after the violence has ended.

Summary

In October 1981, a young boy walking home alone after dusk accepts a ride from a man in a car whose headlights are off. Cold and frightened, he hesitates but eventually gets in.

The driver locks the door, and the boy vanishes into the night—becoming one of several children lost to the island’s hidden predator.

Decades later, in 2016, Massachusetts State Police Detective Tommy Kelly is assigned to Nantucket after construction workers uncover a small human skull. Kelly, a disciplined yet weary investigator with family tensions and an uneasy marriage, reluctantly leaves the mainland.

On the island, he partners with local detective Jo Harris and meets the medical examiner, Dr. Redruth, who confirms the remains belong to a boy aged roughly five to ten, killed by blunt-force trauma.

The deliberate positioning of the skeleton suggests murder. With few leads and decades between the crime and discovery, Kelly and Harris face the daunting task of identifying the child and tracing a killer long gone.

Through flashbacks, the story revisits 1981, when several boys—Richie Sousa, Mikey Parker, and Nick Steuben—went missing. One morning, Richie’s lifeless body was found on a playground swing, his face blue, his body carefully arranged.

The island police, led by a younger Joe Almeida, investigated amid growing panic but without modern forensic tools. A boy named Albie narrowly survived a similar abduction, escaping his captor through intelligence and luck, though his identity was never made public.

The island suppressed the events, shielding itself from outside attention.

Back in the present, Kelly and Harris sift through fragmented records, disintegrated files, and gossip from long-time residents. At the hospital morgue, Dr.

Redruth’s analysis of the bones and decayed clothing narrows the death to between the late 1970s and early 1990s. Among the recovered objects are a few old coins and, crucially, a Luke Skywalker action figure with “NS” carved into its foot.

The toy links the body to the long-missing Nick Steuben—or perhaps his friend Mikey Parker, to whom Nick had lent it before both disappeared.

Chief Almeida, now elderly, confirms the connection and reluctantly revisits the old nightmare. He reveals that in 1981, three boys were abducted and killed by Randal James Hampton, a drifter with a violent past who had been dismantling an abandoned navy base on the island.

Two victims—Richie and Nick—were found posed at public locations, while Mikey was never recovered. When police confronted Hampton in a hidden bunker at Tom Nevers, he drew a gun and was shot dead by Almeida, ending the terror.

The island then sealed off the case, destroying or hiding records to preserve its fragile peace and tourist image.

Kelly and Harris visit Mikey Parker’s surviving family, now elderly and burdened by dementia and grief. Laura Parker, Mikey’s older stepsister, provides a DNA sample, hoping for closure.

Almeida later explains how the 1981 investigation was mishandled and covered up to prevent the island’s economic ruin. The truth, he insists, would have destroyed Nantucket’s reputation.

Harris is disturbed by the complicity, while Kelly senses deeper secrets in Almeida’s guarded tone.

As they continue investigating, new forensic findings complicate the story. The recovered bones show signs inconsistent with Hampton’s known victims—malnutrition, untreated fractures, and blunt trauma from a rounded object rather than strangulation.

Kelly begins to doubt the accepted story: perhaps Mikey wasn’t killed by Hampton at all. His suspicions drive him to revisit old testimonies and family dynamics.

Gradually, he uncovers that the real story is not one of a single killer but a chain of violence buried by shame and protection.

Flashbacks reveal that when Albie escaped the bunker as a child, it was actually Tommy Kelly himself. Almeida and Jimmy Parker, Mikey’s father, found Hampton in the bunker afterward.

In the confrontation, it was Parker—not Almeida—who shot Hampton. Almeida took the blame to protect Parker from prosecution, staging the scene to look like self-defense.

Kelly, who had repressed the truth of his abduction for decades, must now face the realization that he was the survivor everyone on the island sought to forget.

Determined to find justice, Kelly confronts the elderly Jimmy Parker. The man is senile, but Laura, Mikey’s stepsister, still lives in the house.

In a tense exchange, Laura reveals that her devout mother, Susan Parker, was abusive and obsessed with sin and purity. She regularly punished Mikey under the guise of exorcising evil.

Laura confides that she believed her mother accidentally killed Mikey during one of these beatings, and Jimmy buried the body to protect her. But Kelly, piecing together the evidence—particularly the type of skull fracture—realizes Laura herself may have killed Mikey in a moment of anger.

She had played field hockey, and the rounded end of her stick perfectly matches the wound pattern. Faced with his deduction, Laura breaks down and admits she struck her brother during a fit of rage after years of her mother’s cruelty and favoritism.

Her father covered up the crime, and Almeida shielded them both.

As they drive to the station for Laura’s confession, she pulls a concealed pistol, claiming she’ll accuse Kelly of assault to save herself. During the struggle, the gun discharges, killing her as their car crashes off the road.

Kelly survives with a concussion and is later cleared of wrongdoing after internal review. Almeida and Harris visit him in the hospital.

Almeida finally confesses that he recognized Kelly as “Albie” from the beginning and protected him again out of guilt and loyalty to his old promise.

In the aftermath, officials rule Laura’s death a suicide driven by guilt and renewed public attention. The community quietly closes the case.

Harris and Kelly acknowledge the moral weight of what’s been buried—justice and truth both compromised for the sake of peace. Before leaving Nantucket, Kelly stands at the ferry’s rail, throwing coins into the water in memory of the boys who died—Mikey, Nick, Richie—and the frightened child he once was.

As the island fades into the fog, he feels the hold of the past loosen, carrying away secrets long kept by the cold island and its people.

Characters

Tommy Kelly

Detective Tommy Kelly stands at the center of Cold Island, serving as both protagonist and emotional anchor of the narrative. Introduced as a disciplined Massachusetts State Police detective, Kelly is a man of structure and restraint, whose internal battles mirror the darkness of the crimes he investigates.

Beneath his methodical professionalism lies a psyche fractured by trauma—he is, in fact, the very child who survived the 1981 Nantucket abductions. The discovery of the child’s bones drags him into a confrontation not only with a buried crime but also with his own repressed memories.

His sense of duty often clashes with personal turmoil—his failing marriage to Jeanie, his guilt over emotional distance from his sons, and his tendency to submerge pain under routines and alcohol. As the investigation unfolds, Kelly evolves from a man haunted by survival to one who achieves catharsis through truth.

His decision to confront the buried lies of Nantucket, even at the cost of his peace, underscores his moral integrity and emotional courage. By the end, the act of casting coins into the sea symbolizes his attempt to relinquish the burdens of both boyhood and guilt—a quiet redemption that concludes his arc.

Jo Harris

Detective Jo Harris embodies a younger generation of law enforcement—determined, idealistic, and unafraid to challenge authority. As Kelly’s partner in the Nantucket case, she represents both contrast and complement to his reserved demeanor.

Harris’s intellect, curiosity, and persistence often push the investigation forward when bureaucracy and secrecy threaten to halt it. Her youth and inexperience become strengths, allowing her to ask questions that older officers, bound by habit or loyalty, might avoid.

She confronts misogyny and small-town skepticism with measured resilience, maintaining professionalism even when facing hostility. Her relationship with Kelly, which evolves from mutual respect to intimacy, adds emotional complexity.

It becomes a mirror to Kelly’s need for connection and her desire to prove herself in a male-dominated world. By the novel’s end, Harris emerges as both moral compass and inheritor of the investigation’s truth—someone who recognizes the island’s collective guilt yet chooses empathy over condemnation.

Joe Almeida

Chief Joe Almeida is a complex figure—a man whose decades of service on Nantucket are shadowed by moral compromise. Once a young officer during the 1981 murders, Almeida became custodian of the island’s deepest secret: the truth about Randal Hampton’s death and the cover-up surrounding it.

Outwardly gruff but inwardly burdened, Almeida’s loyalty to his community and to the surviving families led him to conceal the real events—protecting Jimmy Parker and young Albie (Tommy Kelly) from legal and psychological ruin. His actions blur the line between justice and complicity.

Though he believes he acted for the greater good, Almeida is haunted by the knowledge that his silence allowed trauma to fester beneath the island’s picturesque surface. His mentorship of Kelly and his eventual confession reveal a man yearning for absolution.

Almeida’s portrayal reflects the moral ambiguity of authority—how protecting one’s community can sometimes mean betraying the truth.

Laura Parker

Laura Parker emerges as one of the most tragic figures in Cold Island. Initially presented as the grieving sister of missing boy Mikey Parker, she later becomes the embodiment of hidden violence and generational pain.

Raised under a mother obsessed with religious punishment and spiritual “cleansing,” Laura grew up in a home ruled by fear and guilt. Her eventual confession—that she killed Mikey in a moment of rage and despair—reveals how cycles of abuse warp innocence into cruelty.

Laura’s act is not born of pure malice but of accumulated trauma, humiliation, and envy. Her father’s subsequent decision to bury the crime and Almeida’s cover-up transform her secret into the island’s unspoken curse.

Her final confrontation with Kelly, ending in her accidental death, completes a haunting symmetry—the survivor of one childhood tragedy forced to witness the truth of another. Laura represents the corrosive power of repression and the high cost of silence.

Jimmy Parker

Jimmy Parker, Mikey’s father and Laura’s stepfather, is depicted as a man trapped between love, guilt, and helplessness. His actions in 1981—shooting Randal Hampton and burying Mikey—stem not from villainy but from a desperate need to protect his family and preserve what remained after unspeakable loss.

The novel portrays him as a man consumed by secrets, gradually eroded by dementia and time. His silence becomes a metaphor for the entire island’s complicity, and his decaying memory reflects the community’s willful amnesia.

Jimmy’s character adds emotional weight to the theme of paternal failure—how love, when twisted by denial, can perpetuate harm.

Randal James Hampton

Randal Hampton, the supposed serial killer of the Nantucket boys, embodies the monstrous face of external evil—but as the story unfolds, his role becomes more complex. A drifter and laborer dismantling the navy base, Hampton is a predator whose prior crimes foreshadow the horror he inflicts upon the island.

Yet his death—revealed to be at Jimmy Parker’s hands, later disguised by Almeida—recasts him as both villain and scapegoat. While he undoubtedly committed heinous acts, his presence in the story serves as a dark mirror for the community’s own capacity for violence.

Hampton’s evil is visible and punishable; the island’s collective concealment is not. His ghost lingers in the narrative as a reminder that the line between monster and man is often defined by who gets to tell the story.

Themes

Childhood Innocence and Its Violation

In Cold Island, childhood stands as both a fragile ideal and a central casualty of human cruelty. The novel’s narrative alternates between the haunting events of 1981 and the investigation in 2016, binding both timelines through the loss of innocence.

The early scenes of children at play—football in the dusk, bikes speeding home through cemeteries, toys and coins clutched as treasures—paint a vivid portrait of ordinary boyhood. These details create a sense of safety and familiarity that makes their destruction profoundly disturbing.

The abductions and murders of Richie, Nick, and Mikey are not merely crimes but symbolic ruptures in the moral fabric of the island community. Even for Albie, who survives, the trauma annihilates his sense of security.

His transformation from a curious, imaginative boy to the hardened adult detective Tommy Kelly reveals the permanent scarring that such violence imprints on the psyche. The preservation of childhood artifacts—the Luke Skywalker toy, the coins, and even the act of scratching initials on them—becomes a tragic echo of the children’s attempt to assert identity against oblivion.

The novel portrays innocence not as naïveté but as something irretrievably lost to both the victims and the adults who fail to protect them. By the time the truth surfaces decades later, innocence has eroded not only in the literal victims but also in those burdened by guilt, silence, and complicity.

The Weight of Secrets and Silence

The culture of secrecy within the island community forms the moral spine of Cold Island. Nantucket, as portrayed in the novel, thrives on concealment—a small, self-contained society where gossip replaces justice and reputation overshadows truth.

The decision in 1981 to bury the reality of the child murders under a layer of civic silence exposes the corrosive nature of collective denial. Chief Almeida’s cover-up, justified as protection for both the surviving child and the island’s economic stability, becomes a generational wound.

The silence does not shield but contaminates, forcing everyone involved into a shared complicity that festers for decades. The physical burial of Mikey’s body mirrors the figurative burial of the truth.

Even Kelly, once the boy “Albie,” grows into a man defined by repression and avoidance, unaware of how deeply the silence around his trauma shapes his life. When the truth begins to surface, the island’s veneer of respectability crumbles, revealing the emotional rot underneath.

The narrative shows how communities maintain their myths by suppressing unpleasant truths and how this very act perpetuates cycles of violence and guilt. Silence, therefore, is not mere absence of speech—it is a deliberate choice that reshapes justice, identity, and memory.

Trauma and Memory

Memory in Cold Island operates like an unstable current—fragmented, unreliable, yet powerful enough to dictate lives. Kelly’s gradual recognition that he was the surviving victim, Albie, is one of the novel’s most compelling psychological arcs.

The buried memories of his childhood abduction and escape, repressed for survival, resurface through his investigation, forcing him to confront the boy he once was. The interplay between past and present reveals how trauma distorts perception, suppresses recollection, and reshapes the self.

The novel’s alternating timelines reflect the disjointed structure of traumatic memory, in which the past constantly intrudes upon the present. Kelly’s physical symptoms—insomnia, nausea, obsessive running—mirror his internal disorientation.

Similarly, the island itself functions as a repository of buried memory: the physical landscape conceals bones and evidence just as the townspeople conceal emotional truths. Memory becomes both a weapon and a burden; it drives Kelly toward resolution but also threatens to undo him.

In recovering the past, he risks reliving it. The novel ultimately presents memory not as redemptive but as necessary—an act of courage that allows both the individual and the community to reclaim moral integrity from the ruins of repression.

Corruption, Justice, and Moral Compromise

The pursuit of justice in Cold Island is filtered through a moral fog where right and wrong lose clarity. From Almeida’s decision to stage Hampton’s death to Kelly’s suppression of Laura Parker’s confession, the novel examines the uneasy boundary between protection and deception.

Each act of concealment is motivated by a twisted form of righteousness—the belief that sparing the innocent or preserving order justifies ethical compromise. Yet these actions reveal how easily institutions of law and morality can deform under pressure.

The police, meant to embody justice, become custodians of secrecy; the killer of children is silenced not through due process but through vigilantism. Even decades later, the investigation operates within political and emotional constraints.

Kelly’s own role as both victim and investigator blurs professional objectivity, showing how personal wounds can warp one’s sense of justice. The novel suggests that truth, when managed or delayed, loses its power to heal.

Justice is reduced to narrative control—the version of events the community can live with. The island’s final acceptance of Laura’s death as suicide epitomizes this moral exhaustion: closure is achieved not through truth but through the illusion of peace.

Isolation and the Burden of Place

The island setting of Cold Island is more than a backdrop—it is a living presence that shapes every human interaction. Nantucket’s physical isolation mirrors the psychological isolation of its inhabitants.

The sea, fog, and winter desolation create a sense of confinement where secrets linger and time seems suspended. This insularity breeds both protection and paranoia; it fosters community bonds while simultaneously enforcing silence and conformity.

The residents’ reluctance to involve outside authorities in the 1981 murders arises from this claustrophobic loyalty to place. For Kelly, returning to the island becomes an act of entrapment rather than duty—each shoreline and landmark pulls him deeper into the geography of his own past.

The contrast between the summer island of tourism and the winter island of ghosts underscores the duality of its existence. Beneath its postcard beauty lies a network of hidden grief and unspoken history.

By the novel’s end, when Kelly casts coins into the sea, the gesture signifies liberation not just from trauma but from the island’s gravitational hold. The place that once sheltered his pain finally releases him, transforming the island from a prison of memory into a graveyard of secrets where peace can, at last, exist.