Elsewhere by Gabrielle Zevin Summary, Characters and Themes

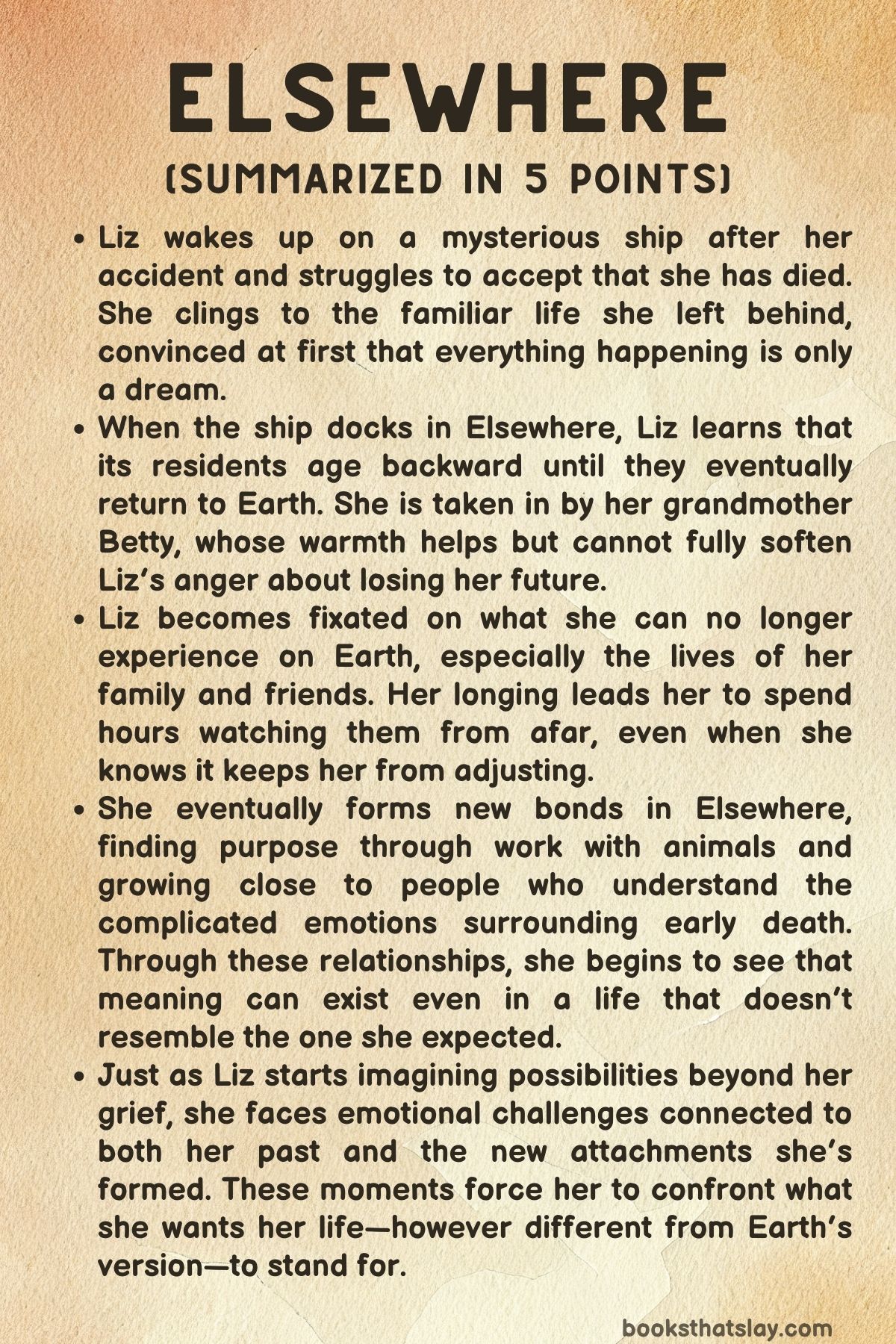

Elsewhere, written by Gabrielle Zevin, is a novel that imagines an afterlife both familiar and strange. It follows fifteen-year-old Liz Hall, who dies unexpectedly and wakes up in a world where no one grows older.

Instead, everyone ages backward until they return to Earth as infants. Through Liz’s eyes, the story explores grief, longing, second chances, and the unexpected ways people learn to live even after life ends. The book balances humor with loss, focusing not only on what is gone but on what remains possible. At its core, it asks what it means to grow, love, and let go.

Summary

Elsewhere begins with the aftermath of Liz Hall’s sudden death in a road accident. While her family and dog struggle with their loss on Earth, Liz awakens aboard a mysterious ship called the SS Nile.

At first she is convinced she is dreaming, but as she meets other passengers—including her new friend Thandi and Curtis Jest, a musician she admired—she starts to accept the truth: she has died. The ship is sailing toward a place called Elsewhere, where all people go after death.

When the boat docks, Liz is greeted by her grandmother Betty, who died before Liz was born. Betty appears decades younger than Liz expected, and she soon reveals why: in Elsewhere, everyone ages backward.

Liz, who arrived at fifteen, will gradually grow younger until she becomes a baby, at which point she will be sent down the River back to Earth for a new life. Liz is devastated.

She mourns the future she will never have—turning sixteen, college, falling in love, and all the small freedoms she imagined. Betty tries to help her adjust, showing her their neighborhood and explaining the daily life of Elsewhere, but Liz can barely bring herself to participate.

At her acclimation meeting, Liz learns that residents choose avocations instead of careers, there is no illness, and contacting the living is strictly forbidden. None of this eases her resentment.

She becomes obsessed with watching her family on Earth through the Observation Decks, where special binoculars show brief glimpses into living people’s lives. Liz spends nearly all her time there, tracking her parents’ grief, her brother Alvy’s confusion, and her best friend Zooey’s attempts to move forward.

The connection comforts her, but it also traps her in longing and prevents her from embracing her new existence.

When Liz discovers her death was caused by a hit-and-run taxi driver, she becomes determined to identify him. After many hours at the Observation Decks, she finds the driver, Amadou Bonamy, and is surprised that he seems gentle and remorseful.

Her desire for justice becomes complicated, but her fixation on Earth does not fade. When Curtis Jest mentions a dangerous way to make Contact through a location called the Well, Liz becomes determined to try it.

She believes her family deserves the truth about the sweater she hid as a gift for her father before she died, and she convinces herself that this mission justifies the risk.

Liz dives to the Well despite the law forbidding it. The Well allows voices to cross briefly into the living world through water sources.

Liz manages to alert Alvy about the sweater, but her message is confusing and frightening for her family. Before she can finish speaking, she is captured by a tugboat crew led by Detective Owen Welles, who works for the Bureau of Supernatural Crime and Contact.

He confiscates her equipment, warns her of the harm she caused, and bans her from the Observation Decks. Though angry at first, Liz eventually realizes he was trying to protect both her and her family.

Owen later makes a dive himself to correct the misunderstanding, ensuring Liz’s father finds the sweater and understands its significance. Grateful and moved, Liz invites Owen to Thanksgiving at Betty’s house.

A friendship grows between them and gradually becomes something deeper. Owen adopts a dog, and he and Liz spend more time together—cooking, practicing driving, and sharing small daily moments.

Eventually, they admit they love each other.

Just as Liz begins to feel hopeful about her new life, she learns that Owen’s wife Emily is about to arrive in Elsewhere. Owen is overwhelmed when Emily disembarks, and Liz, though heartbroken, steps aside out of respect for their past.

Owen tries to rebuild a life with Emily, who struggles with her allergies to his dog Jen and with the strange rules of aging backward. Liz, meanwhile, agrees to care for Jen.

Though she hides it, Liz resents Emily’s return and mourns what she has lost.

In time, Liz and Owen find a fragile peace, though not a romantic one. Liz focuses on her work at the Division of Domestic Animals, becomes close again with her friends, and supports Betty when Curtis Jest tries, with awkward sincerity, to court her.

A crisis erupts when Liz, overwhelmed by confusion about her future, secretly attempts a second return to Earth through the River. She regrets the decision almost immediately, fights her way free, and nearly dies in the attempt.

Owen rescues her in a dramatic search, and Liz slowly recovers, surrounded by people who love her.

As the years pass, Liz grows younger and more comfortable with who she has become. Curtis eventually marries Betty, giving Liz a new family structure in Elsewhere.

Liz reunites with her old dog Lucy when Lucy dies on Earth, and she finally meets Amadou Bonamy, offering him forgiveness and easing his years of guilt. Liz also makes peace with her own past when she and Owen briefly join forces to deliver a message of love to her brother Alvy during her best friend Zooey’s wedding celebration.

Time continues its backward march. Liz becomes a child, then a toddler, gradually forgetting the complexities of her older life.

Owen also ages backward, and their memories of each other fade into something soft and distant. Finally, when Liz becomes an infant, she is brought once again to the River for Release.

Betty, Owen, and the friends she made in Elsewhere gather to send her on her next journey.

Wrapped and carried by the current, baby Liz drifts away, sensing love, hope, and the promise of beginnings rather than endings. On Earth, a newborn girl enters the world at sunrise, laughing as she opens her eyes.

Characters

Liz Hall

Liz is the emotional center of Elsewhere, and her character arc is essentially a second coming-of-age that happens after death. At fifteen, she is suspended between childhood and adulthood, and death freezes her exactly at that moment of unfinished possibility.

Early on, Liz is defined by shock, denial, and resentment. She clings to the idea that she is in a dream, that someone made a mistake, that she deserves to grow up, get a license, fall in love, and live the life she imagined.

Her fixation on lost milestones shows how much she equates life with forward progress, achievements, and a conventional future. At first, she has very little capacity to see beyond her own pain, and even the kindness of others in Elsewhere feels like an insult to the life she has been cheated out of.

As Liz begins using the Observation Decks, we see her grief turn into obsession. She watches her family and friends as if binging a series, reducing living people to scenes she can rewind and analyze.

This behavior shows both her deep love and her emotional immaturity. She wants to be present without accepting the cost of absence; she wants influence without responsibility.

Her fixation on the hit-and-run driver and the Well grows out of this mindset. Liz believes that justice, or at least information, will restore some kind of balance.

But in practice, her attempted Contact only harms the people she loves, forcing her to confront a painful truth: love in death sometimes means stepping back, not pushing in.

A turning point in Liz’s growth comes through work and relationship. At the Division of Domestic Animals, she discovers an avocation that is not about grades or resumes but about meaning and compassion.

Counseling confused animals mirrors her own confusion and lets her offer the empathy she struggled to give herself. Liz’s friendship with Thandi and her bond with dogs like Sadie and later Jen anchor her in Elsewhere.

Her relationship with Owen complicates her emotional life further. Through Owen, Liz experiences romance in a place where time moves backward, which forces her to redefine love not as part of a typical life path but as something that can exist even within limits, impermanence, and competing loyalties.

Liz’s decision to dive to the Well for the sweater, and later to attempt returning to Earth entirely, reveal an enduring restlessness and fear of “wasting” her death. She struggles with a belief that only a forward, Earth-bound life is real.

It is only after nearly dying a second time at the bottom of the ocean that she truly understands Elsewhere as its own life, not a waiting room. Her eventual acceptance of growing younger, forgetting, and finally being Released as a baby shows how far she has come.

She moves from entitlement to gratitude, from clinging to control to trusting the strange kindness of the universe. By the end, Liz is no longer a girl furious about what she missed; she is someone who recognizes that backward and forward lives can both be full, and that love is not erased by change or rebirth.

Lucy

Lucy begins as a grieving dog on Earth and becomes a quiet emotional thread tying Liz’s earthly life to her afterlife. In her opening scenes, Lucy observes human rituals of mourning with confusion and skepticism.

She hears Liz’s parents reassure themselves that Liz’s death was quick and painless, and while she doubts it, she wants to believe it for Liz’s sake. Lucy’s inner life reveals how deeply she is attached to Liz as her person.

Bandit’s suggestion at the dog park that humans are interchangeable horrifies her because Liz is not a generic caretaker; she is Lucy’s specific human, and that one-of-a-kind bond helps shape the novel’s understanding of love.

Lucy’s grief is animal, immediate, and practical. She worries about hunger and comfort even while feeling guilty for those needs, reflecting a tension that also exists in the human characters: life continues, needs persist, even in the shadow of death.

For Lucy, the natural order feels broken when a dog outlives her person. This sense that the world has turned upside down echoes Liz’s own feeling of cosmic unfairness after her death.

Later, after Lucy herself dies and comes to Elsewhere, she becomes a source of comfort and continuity for Liz. Reuniting with Lucy lets Liz experience that some separations are temporary and that love can literally cross worlds in this universe.

Lucy’s journey from Earth to Elsewhere and back to Liz reinforces the novel’s idea that bonds with animals are as meaningful as bonds with humans and that these relationships help people survive emotional upheaval.

Thandi Washington

Thandi is Liz’s first real companion in the afterlife and a vital emotional foil. She initially appears as a calm, practical girl who already suspects the truth Liz refuses to name.

While Liz clings to denial, Thandi methodically reconstructs the memory of being shot in the head on a street in D. C.

Her willingness to face her death head-on shows a kind of courage and clarity that Liz lacks at first. Thandi’s matter-of-fact acknowledgment that she was murdered, and that this place is not a dream, challenges Liz’s fantasy that she can simply wake up or turn back time.

As the story progresses, Thandi embodies a slightly different kind of grief. She, too, has lost a future, but she is more open to building a new life in Elsewhere.

She adopts Paco, the anxious Chihuahua, and makes pragmatic choices like reading arrival lists for her broadcast. Thandi’s humor and bluntness provide emotional balance: she teases Liz for romanticizing adventure after death, observing that dying once is more than enough “adventure” for a lifetime.

Her comments force Liz to see that constantly chasing drama and big moments can be a way of avoiding the slower, quieter work of healing.

Thandi’s warning about Emily’s arrival and her support during the Owen–Liz–Emily triangle show her loyalty and protectiveness toward Liz. She is willing to deliver painful news because honesty matters more to her than temporary comfort.

Over time, Thandi’s presence reminds Liz that friendship in Elsewhere is not a consolation prize; it is a central part of this second life. Thandi herself gradually accepts backward aging, continuing to nurture new relationships and responsibilities rather than clinging to what she has lost.

In this way, she models a kind of grounded resilience that helps Liz (and the reader) understand that acceptance is not the same as forgetting.

Curtis Jest

Curtis Jest, the blue-haired rock star from Liz’s favorite band, Machine, embodies the complexities of fame, self-destruction, and second chances. On the SS Nile, he is both a celebrity and a lost soul.

His casual admission that he “used to be” Curtis Jest, along with the track marks on his arms, undercuts Liz’s romantic ideas about rock stars and shows the human cost of his former lifestyle. Curtis does not fit neatly into the role of tragic hero or cautionary tale.

Some days he did want to die a little, and most days he did not, which captures the ambiguity of addiction and self-harm without simplifying it into a single choice.

In Elsewhere, Curtis gradually transforms from a symbol to a person. He becomes a friend to Liz, offering her the knowledge of forbidden Contact and later stepping up in quiet, selfless ways.

His decision to dive to the Well to fix the chaos Liz’s attempt created for her family is a powerful act of atonement. Curtis has already learned, through painful trial and error, how dangerous repeated Contact can be, but he is willing to risk a controlled, careful dive for Liz’s sake.

In doing so, he restores not only the cashmere sweater to Liz’s father but also Liz’s sense that her love was understood.

Curtis’s romantic interest in Betty is another key layer of his character. At first, his crush seems comic and unlikely: a young-looking rock star in love with a grandmother who insists she is “through with romance.

” But his persistence, vulnerability, and eventually “The Betty Song” show that he is capable of deep, sincere love outside the performative world of concerts and fans. Betty’s acceptance of him signals that Curtis has moved beyond his past as a self-destructive icon to become a partner, friend, and family member.

By the time he marries Betty, Curtis represents the possibility that even those who died in messy, tragic ways can build something gentle and meaningful in their next life.

Betty Bloom

Betty Bloom, Liz’s grandmother, is both a personal anchor and a guide to the logic of Elsewhere. Having died of breast cancer before Liz was born, she exists for Liz only as a myth on Earth.

Meeting her in Elsewhere turns that myth into a warm, flawed, and fiercely loving person. Betty’s backward age—arriving at fifty and now in her thirties—symbolizes her own second chance at life, but her emotional role is firmly maternal and grandmaternal.

She welcomes Liz at the dock, explains the rules of Elsewhere, and tries to balance honesty with gentleness as she reveals that Liz will never turn sixteen in the way she imagined.

Betty’s parenting style is notable for its combination of structure and compassion. She gives Liz money but also expects repayment, which later leads Liz to experience the satisfaction of clearing a debt.

She lets Liz drive the convertible as a distraction but firmly takes over the wheel after the crash, modeling that even in a world where death has already happened, actions have consequences and safety matters. When Liz breaks the rules by diving to the Well, Betty’s reaction is not fury but shaken concern.

She supports Liz through the aftermath, suggesting the list exercise and encouraging her to either let go of or reclaim the things she misses. That emotional flexibility makes Betty feel real and grounded rather than idealized.

Betty’s own arc, though quieter, is deeply moving. She insists early on that she is done with romance, perhaps as a defense against further hurt, yet she slowly opens herself to Curtis’s affection.

Her eventual marriage to Curtis in her own garden is a testament to her ability to embrace joy even after death, illness, and losing a child on Earth. At the end of the novel, Betty must perform the excruciatingly loving act of bringing baby Liz to the River for Release.

Her farewell speech about good and sad things coexisting crystallizes the emotional philosophy of Elsewhere. Betty understands that love often means letting go, and she becomes the embodiment of a compassionate guide who accepts the universe’s cycles without ceasing to grieve or care.

Owen Welles

Owen Welles represents the tension between past and present love, duty and desire, and the difficulty of moving on after a traumatic death. His backstory as a New York firefighter who dies in a routine fire trying to save a cat makes him both quietly heroic and tragically ordinary.

The fact that his death is not in some grand disaster but in a relatively mundane rescue emphasizes the randomness of mortality. In Elsewhere, Owen initially cannot accept his death and throws himself into repeated illegal dives to Contact his wife, Emily.

His record of 117 dives shows his obsession and desperation, but also how Contact harms the living more than it comforts the dead. Taking a job with the Bureau of Supernatural Crime and Contact is his attempt to atone and impose order on the chaos he once contributed to.

When Owen meets Liz, he is older emotionally but younger in appearance, creating an intriguing imbalance in their relationship. At first, he is the authority figure who stops her illegal dive, confiscates her gear, and lectures her on the damage she has done to her family.

Yet he is also empathetic, carrying the weight of his own mistakes. His later dive to the Well to fix Liz’s sweater situation is an act of quiet generosity, motivated by his own experience of how crucial small gestures can be for the living.

This combination of rule-enforcer and secret helper makes Owen feel layered and morally complex.

Owen’s developing romance with Liz is tender but also complicated by his enduring attachment to Emily. He is cautious about physical intimacy and defines real closeness as something mundane and domestic, like brushing teeth together, which reflects his longing for everyday companionship rather than dramatic passion.

Liz helps him reinhabit the present of Elsewhere instead of living only in memories of Earth. However, Emily’s arrival reopens all his unresolved loyalties.

Owen’s decision to meet Emily and take her home, even while he still loves Liz, reveals his strong sense of responsibility and the unfinished emotional business he carries. His choices hurt Liz deeply, but they also show that love cannot be neatly replaced; people can love more than one person in different ways at different times.

By the time Owen and Liz regress to childhood, their romantic history has softened into something like a shared game that Liz no longer fully remembers, but his gold watch gift and repeated rescues suggest that his care for her endures beyond any single label.

Aldous Ghent

Aldous Ghent, Liz’s acclimation counselor, provides the bureaucratic, philosophical backbone of Elsewhere. He is the one who introduces Liz to the rules of this afterlife: the necessity of an avocation, the prohibition on Contact, the process of aging backward, and the general principle that time, more than anything else, tends to heal.

Aldous functions much like a guidance counselor or social worker, easing people into a reality they never chose while upholding a system that is larger than any individual’s feelings. His calm demeanor contrasts strongly with Liz’s emotional turmoil, which at first makes him seem distant or unsympathetic.

However, Aldous is not cold. He offers Liz a job working with domestic animals because he senses her capacity for empathy and her deep bond with her dog.

He keeps following up, showing an interest in her adjustment over time. Later, when Liz is in the healing center after nearly dying in the River, Aldous visits to talk about Shakespeare and death, revealing a more reflective side.

Through him, the book hints at broader existential questions: what makes a life meaningful, what role work plays when survival is no longer at stake, and how individuals can find purpose in a system they did not design. Aldous is not a revolutionary, but he is a humane administrator, committed to helping people like Liz discover that this strange place can still hold joy and growth.

Alvy Hall

Alvy, Liz’s younger brother, shows the impact of Liz’s death on a child and plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between Earth and Elsewhere. He begins as the little boy who picks up Lucy and promises to take care of her now that Liz is gone, trying to step into a role he is too young to fully understand.

Alvy’s belief that Liz might be “up there” with angels reflects how children use simple, sometimes cliché images to make sense of incomprehensible loss. He is both the family clown who uses humor to cope and the person most open to sensing Liz’s presence when she Contacts them.

During Liz’s chaotic first dive to the Well, Alvy is the only one who perceives her amid the cacophony of running water. His sensitivity makes him Liz’s most receptive link to the living world, but it also puts him at risk of confusion and emotional harm, as seen when the miscommunication almost leads to him being hit by their father.

Later, Owen’s careful, second dive to clarify the sweater’s location allows Alvy to play a heroic part in bringing that hidden gift to light. This validates his sense that his sister is still connected to him in some way.

The most emotionally satisfying moment between Liz and Alvy comes at Zooey’s wedding, when Alvy follows Liz’s voice from room to room until he finds her in the courtyard fountain. Their conversation, brief and heartfelt, allows both siblings to acknowledge their love and apologize for any unspoken hurts.

Alvy’s simple updates about school and life, and Liz’s reassurance that she is okay in Elsewhere, offer mutual closure. Alvy’s arc underscores how siblings experience grief differently from parents and how a single meaningful connection, even filtered through magical plumbing, can help a child move forward.

Liz’s Parents

Liz’s parents are never as fully foregrounded as Liz herself, but they embody adult grief, guilt, and the struggle to keep living after losing a child. Early on, they repeat to each other that Liz’s death was quick and painless, clinging to a narrative that eases their own unbearable sense of failure.

We see them largely through Liz’s and Lucy’s perceptions or via the Observation Decks, which creates an emotional distance that mirrors the literal distance between worlds. Liz’s mother sleeping in her room, her father’s breakdown after nearly hitting Alvy, and their ongoing attempts to function as a family all reveal how grief can fracture and reshape everyday routines.

The sea green cashmere sweater becomes a concentrated symbol of Liz’s relationship with her father. Her torment over whether he will ever find it shows how important it is to her that he knows she thought of him and loved him.

When Owen’s dive finally directs Alvy to the correct closet and Liz’s father discovers the sweater, his reaction closes a loop of love and grief. He understands that the gift was meant for him, and that his daughter cared in a deeply intentional way.

Liz’s parents do not stop grieving, but the sweater offers a tangible connection that softens some of their pain. They stand for all the living people in Elsewhere whose stories continue offstage, carrying loss but also the possibility of healing.

Zooey

Zooey, Liz’s best friend on Earth, illustrates how friendship and grief are both deeply personal and often misunderstood by outsiders. Through the Observation Deck, Liz watches Zooey’s mourning with an uneasy mix of jealousy, resentment, and longing.

She notices who comes to the funeral, who does not, and obsesses over the ways Zooey lives on: preparing for prom, getting dressed, interacting with others. At times, Liz resents Zooey for continuing to experience milestones Liz herself has been denied.

This reaction exposes Liz’s fear that she will be forgotten or replaced.

The revelation that Zooey did not attend Liz’s funeral initially wounds Liz deeply, confirming her worst fears about being abandoned in death. But the later arrival of Zooey’s wedding invitation and heartfelt note complicate that narrative.

Zooey’s message explains her absence and expresses enduring love, revealing that grief can be messy, paralyzing, and not always aligned with socially expected rituals. When Liz and Owen dive to speak at the wedding reception, Liz’s attempts to speak through sinks and pipes fail, leading only to a startled busboy.

Yet the fact that Zooey wrote, invited her, and continues to care becomes more important than whether Liz manages a supernatural toast. Zooey’s life moving forward, culminating in her marriage to Paul, symbolizes the truth that the living must go on, even if it hurts those who have died to watch.

Emily Welles

Emily Welles, Owen’s wife, enters the story late but carries enormous emotional weight. On Earth, she lived through Owen’s death, completed medical school, became a burn specialist, and even experienced the trauma of losing a pregnancy after his death.

By the time she dies of the flu and arrives in Elsewhere, she has had a decade of grief and growth that Owen has not fully seen, since he only watched her in limited glimpses from the Observation Deck. Her arrival forces everyone, especially Owen and Liz, to confront the realities of long-term love and loyalty.

Emily’s reaction to Elsewhere mixes joy at seeing Owen with confusion about her sudden youth and the loss of her career and earthly identity. She is pragmatic yet emotionally intense, trying to rationalize away her dog allergies so she can accept Jen, then having to face the physical limitations that come with her body.

Her willingness to consider a new avocation, such as becoming a keeper of books, suggests an openness to reinvention, but she also carries a heavy history. When she tells Owen that she had been pregnant and lost their baby after his death, it reveals a layer of shared grief they never got to experience together.

This confession hits Owen hard and changes how the reader understands both of them: Emily is not merely the “first wife” obstacle between Owen and Liz, but a person whose pain and love are as valid as anyone else’s.

Emily’s presence complicates any simple idea of a “right” romantic pairing. She and Owen loved each other first and endured enormous loss, while Owen and Liz built a relationship that helped him stop living entirely in the past.

The book does not provide an easy resolution to this triangle as the characters regress to childhood and their adult relationships fade. Emily’s role ultimately underscores that love does not obey neat timelines and that people can be important to each other in multiple, overlapping lives.

Jen

Jen, the golden retriever who chooses Owen at the Division of Domestic Animals, is both comic relief and an emotionally significant character. Through Liz’s translations, we see Jen as a straightforward, enthusiastic soul who wants a human to love and clear conditions for the relationship.

Her questions and “contract” with Owen highlight the mutual responsibility in pet ownership; she is not merely a passive recipient of affection but a partner with expectations and emotional needs.

When Emily arrives and her dog allergies flare, Jen finds herself unwanted in her own home. Owen’s decision to temporarily place Jen with Liz may be practical, but for Jen it feels like rejection.

Her attempts to impress Emily, followed by the failure of those efforts, make her a quiet victim of the complex human emotional tangle. At the same time, Jen’s influence is significant: she is the one who helps Owen pick out the gold watch for Liz, and her presence in both Owen’s and Liz’s lives weaves them together.

Jen represents the way animals in Elsewhere are more than accessories; they are moral and emotional touchstones that reveal how humans treat those who depend on them.

Sadie

Sadie is Liz’s dog in Elsewhere and an integral part of Liz’s healing. Working at the Division of Domestic Animals, Liz is assigned to help dogs adjust to death and new circumstances, and Sadie becomes both her coworker of sorts and her beloved companion.

Sadie’s loyalty, simple joy, and occasional confusion are exactly what Liz needs as she tries to build a life that is not centered on watching Earth. Through walks, work, and everyday routines with Sadie, Liz experiences a kind of domestic happiness she feared she would never have.

Sadie’s backward aging and eventual Release down the River mirror Liz’s own trajectory and foreshadow what Liz will later face. Liz is terrified when Sadie is sent down the River as a puppy, because it feels like losing a loved one all over again.

Yet the arrival of Lucy after Sadie’s Release shows that love cycles on; new arrivals and reunions are woven into the structure of Elsewhere. Sadie’s arc reinforces the theme that relationships are temporary in form but enduring in impact.

Paco

Paco, the nervous Chihuahua adopted by Thandi at Liz’s urging, represents the healing power of care in miniature. He is initially confused and frightened by his new environment, much like many human arrivals.

Thandi’s decision to adopt him, coached by Liz, enables both of them to exercise compassion and responsibility. Paco’s presence in Thandi’s life mirrors Liz’s bond with Sadie and later Jen, demonstrating that sharing life with another creature is a way of making Elsewhere feel like home.

Paco may not drive major plot events, but he helps fill in the everyday emotional texture of this world.

Dolly

Dolly, the launch nurse who wraps people for Release, appears both at the beginning and the end of Liz’s Elsewhere life. Her role seems clinical and procedural: she swaddles the soon-to-be infants, leaves their faces exposed, and oversees their descent into the River.

Yet Dolly is also a kind of midwife of death and rebirth. Her careful wrapping of Liz before the River, and later her role in Liz’s final Release as a baby, are acts of ritual care.

Dolly’s presence underscores that the process of ending one life and beginning another is both ordinary and sacred in Elsewhere. She treats it not as a tragedy but as a necessary transition, which helps normalize the cycle for characters and reader alike.

Doris, Myrna, and Florence

Doris, Myrna, and Florence, the trio of elderly women Liz and Thandi meet in the ship’s dining room, offer an important perspective on age and death. They are fascinated by how young Liz and Thandi are and gently ask what happened to them, which highlights the unnaturalness of teenage death compared to dying old.

Through their curiosity and stories, they normalize the experience of arriving in Elsewhere at the end of a long life, suggesting that for many, death comes after a full earthly journey. Their presence helps Liz see that her experience is unusual but not solitary; she is entering a community of the dead that spans generations.

The three women add warmth and a kind of grandmotherly chorus to the early sections of the story.

Bandit

Bandit, the mutt at the dog park, represents a cynical, survival-oriented view of human–animal relationships. His claim that humans are interchangeable and that dogs should simply find another person as needed shocks Lucy and exposes a more transactional way of seeing companionship.

While Bandit’s attitude is off-putting, it also reflects a truth about how some beings cope with loss: by minimizing attachment and insisting on replaceability. Bandit’s brief appearance helps sharpen the contrast between Lucy’s fierce loyalty and a more guarded, self-protective approach to love.

Amadou Bonamy

Amadou Bonamy, the cab driver who hits Liz in the accident, initially exists in Liz’s mind as a faceless villain. Her obsession with finding him through the Observation Decks is fueled by the need to assign blame and make sense of her death.

When she finally locates him and discovers that he is a kind, responsible man with a family, her anger becomes more complicated. He is not a monster but a human being who carries guilt and fear.

The later meeting between Liz and Amadou in Elsewhere completes this arc. Amadou confesses his terror and sorrow, and Liz tells him she forgave him long ago and that her life has been good.

This exchange frees both of them: Amadou from paralyzing guilt, and Liz from the lingering idea that her death was the result of some cosmic enemy. His character reinforces the novel’s message that tragedy can arise from ordinary people making mistakes, and that forgiveness is a powerful way to move beyond those moments.

Themes

Grief and Mourning

Grief in Elsewhere appears in multiple registers at once: human, animal, and even institutional. The opening image of Lucy the pug listening to Lizzie’s parents rehearse the phrase “quick and painless” already suggests that mourning is both an emotional and a narrative process: people tell themselves stories to survive what has happened.

Lucy doubts the story yet wants to believe it for Lizzie’s sake, capturing how grief is full of contradictions—comforting lies coexisting with painful truths. On the ship and then in Elsewhere, Liz’s own grief looks very different.

She is not grieving a person but grieving her own future, a life she believed she was owed: a driver’s license, college, romances, and the long corridor of adulthood. Her anger, numbness, and obsession with the Observation Decks show a different aspect of mourning: the refusal to accept that what is lost cannot be reclaimed.

The book shows how grief is not limited to the living mourning the dead; the dead mourn, too, for what might have been. Liz’s parents and Alvy move through recognizable stages of grief on Earth—rituals, funerals, misdirected anger, long-term sorrow—while Liz reflects their process back from Elsewhere, sometimes misunderstanding it, sometimes clinging to it as proof that she still matters.

Thandi’s story adds another layer: she accepts her death more quickly than Liz, yet her shooting is senseless and violent, exposing how grief is often entangled with injustice. By distributing sorrow across species (Lucy, Sadie, Jen), generations (Betty, Liz, Alvy), and worlds (Earth and Elsewhere), the novel suggests that mourning is a common language.

It hurts, it distorts judgment, it tempts people into unhealthy fixation, but it is also a testament to deep bonds. Grief, the narrative suggests, is not something to “get over” but something that slowly reshapes into a different kind of love and remembrance as time—forward or backward—goes on.

Acceptance of Death and the Afterlife

Death in Elsewhere is not a single moment but a long, contested process of recognition and acceptance. Liz’s journey starts in absolute refusal: she insists the ship is a dream, searches for loopholes, plans to stow away back to Earth, and treats the rules of Elsewhere as negotiable impositions rather than realities.

This resistance reflects how people often meet death psychologically, even when they are technically still alive—by denying, bargaining, or imagining miraculous returns. The SS Nile, the Observation Decks, and the bureaucratic calm of the Registry present an afterlife that is almost banal in its normalcy.

There are forms to fill out, appointments to attend, orientation videos to sit through. This everyday texture prevents death from being a purely mystical event; instead, accepting death means accepting a new kind of ordinary.

Liz’s arc shows that acceptance does not arrive as a single epiphany but in repeated, painful stages: watching her funeral, discovering the hit-and-run truth, learning about Release, and finally confronting the fact that she cannot both cling to Earth and build a life in Elsewhere. The illegal dive to the Well is a desperate attempt to resist acceptance by proving that she can still correct and control events among the living.

When that fails and harms her family, she is forced to reconsider what “doing right” means when one no longer belongs to the living world. Owen’s backstory mirrors and complicates this dynamic.

His record-setting dives and obsessive contact with Emily show a more extreme version of what Liz attempts, and his eventual decision to stop watching Emily regularly marks a hard-won acceptance. The novel frames acceptance not as forgetting or ceasing to care but as recognizing the boundary between worlds, honoring love for the living without trying to direct their lives.

Acceptance, in this sense, is both surrender and courage: the willingness to invest in a life that is undeniably limited yet still meaningful.

Time, Aging, and the Shape of a Life

The backward aging structure in Elsewhere challenges conventional ideas about what a life is supposed to look like. Typically, people imagine life as a straight line toward maturity, achievement, and then decline.

In Elsewhere, people arrive at their death age and then grow younger until Release, at which point they begin again as babies on Earth. This reversal forces Liz, and the reader, to question which parts of life are “essential.

” Liz is outraged at first because the milestones she expected—sixteen, college, adult independence—are stolen. Yet as she moves from fifteen to fourteen and onward, she discovers that meaning does not depend on reaching particular ages or checking off prescribed milestones.

The novel uses mundane details—earning eternims, owning a car, going to work, celebrating holidays—to show how a “truncated” life is still full, just oriented differently. Time in Elsewhere is also merciful in its healing function.

Physical wounds vanish as people grow younger: Liz’s stitches disappear, injuries from accidents fade, and illness does not exist. Emotional wounds, however, do not obey the same neat reversal.

Owen still carries the pain of his death and Emily’s loss; Betty still remembers dying of cancer and missing her daughter’s early adulthood. The reverse aging system allows for second chances in unexpected ways: older people who died bitter or rigid have time to loosen, be playful, and try new avocations.

Children who died very young gain enough years to form friendships and attachments before Release. The circular flow from Earth to Elsewhere to Earth again suggests that life is not a single arc but one movement within an ongoing cycle.

Importantly, this structure refuses to sentimentalize immortality. There is a clear endpoint even in Elsewhere: when a person reaches babyhood, that particular identity dissolves.

The book uses this to ask whether a life’s value lies in its length or in the quality of attention and connection within whatever span is given, forward or backward.

Identity, Adolescence, and Selfhood

Liz arrives in Elsewhere as a typical modern teenager, constructing her identity through external markers: grades, a driver’s license, clothes, music fandom, romantic possibilities, and the sense that everything important lies ahead. The car accident and sudden appearance in Elsewhere rip away these defining features, leaving her in a liminal state where she is no longer who she was but not yet someone new.

Early on, she clings to remnants of her Earth-self as proof of continuity: the stitches on her head, her bitterness about her last word being “um,” the hidden cashmere sweater, and the fantasy that she will return to her old life as a “miracle survivor. ” Adolescence is often described as a time of transition, but Liz is forced into an extreme version of this, where the usual markers of becoming—graduation, legal adulthood, career—simply do not exist.

In their place, she must construct a version of self that does not rely on the linear progression she expected. This is where her job at the Division of Domestic Animals, her friendships with Thandi and Curtis, and her relationship with Owen become crucial.

Through these roles and connections, she starts to see herself not as a “girl who died too young” but as someone with skills, preferences, and responsibilities in the present. The reverse aging complicates identity further: as she grows younger, her cognitive and emotional capacities slowly shift, and the adult feelings she and Owen share begin to melt away.

The novel does not present this as simple tragedy; instead, it suggests that identity is both resilient and fluid. Liz remains herself even as she forgets details and loses abilities, and she will, in some sense, be herself again on Earth, though with no explicit memory.

Adolescence in this story becomes less about reaching a stable, final version of self and more about learning to live with change, uncertainty, and the knowledge that no identity—teen, adult, or child—is guaranteed to last forever.

Love, Connection, and the Complexity of Relationships

Human connection in Elsewhere is never simple, and love appears in many forms that conflict, overlap, and challenge each other. Familial love is present from the first scene, as Lizzie’s parents try to protect each other with the story of a “quick and painless” death, and later in Liz’s fierce attachment to her family from afar.

Betty’s love for Liz is particularly powerful because it begins at a distance; she never met Liz while alive, yet in Elsewhere she steps immediately into the role of guardian, chauffeur, co-conspirator, and emotional anchor. Their relationship demonstrates that family is not only about shared time but also about willingness to care once circumstances finally allow it.

Romantic love is presented through both Liz and Owen and Owen and Emily, forming a triangle that resists easy moral judgment. Owen genuinely loves both, but in different ways and at different life stages.

His loyalty to the memory of Emily initially blocks him from fully committing to Liz, and when Emily arrives, the past confronts the present in a very literal way. Liz’s pain at being asked to step back is understandable, and the story does not punish her for feeling that hurt.

At the same time, Emily’s grief, her lost pregnancy, and her own disrupted life demand empathy. The novel allows for the possibility that love can be real and deep in more than one direction, and that sometimes the “right” choice is simply the least harmful one.

Meanwhile, the bonds between humans and animals—Lucy and Lizzie, Liz and Sadie, Owen and Jen—are treated as equally significant. Animals are not mere symbols; they have personalities, preferences, and the capacity for loyalty and jealousy.

Jen’s sadness over Emily’s dog allergies and eventual placement with Liz reflects the way relationships sometimes fail due to factors no one controls. Across all these connections, love is shown as companionship, obligation, comfort, frustration, and, crucially, choice.

Characters repeatedly choose to keep caring even when it hurts, and that ongoing choice, more than grand declarations, gives love its depth in the story.

Letting Go, Non-Interference, and the Ethics of Contact

The rules against Contact in Elsewhere create a moral problem at the heart of the book: if you could speak to the people you left behind, should you? Liz’s obsession with the Observation Decks shows how easily watching becomes a kind of emotional surveillance.

She convinces herself that she needs to know how her family is doing, but the knowledge does not bring peace; it keeps her suspended between worlds, unable to invest fully in either. The discovery that her death was a hit-and-run intensifies this, transforming her observation into a mission for justice.

From Liz’s point of view, Contact seems not only desirable but ethically necessary: she wants the truth revealed and her parents’ grief acknowledged properly. The Well offers a dangerous loophole: a way to speak through water to the living.

Liz’s first dive results in confusion and near violence when her father almost strikes Alvy in anger, dramatizing how partial, distorted communication can harm more than it helps. Owen’s history complicates the picture further.

His 117 dives to reach Emily, meant as acts of love, ended up sabotaging her attempts to heal and rebuild her life. His eventual decision to make a single, careful dive on Liz’s behalf—successfully guiding Alvy to the sweater—is portrayed as an exception born from hard-won wisdom.

Even that success does not erase the general rule: the living need the freedom to adapt without ghostly interference. The later, gentler Well dive for Zooey’s wedding reinforces this ethic.

Liz fails to deliver a formal toast; instead, a quiet conversation with Alvy emerges, full of mutual reassurance and acceptance. The novel suggests that letting go of control over the living is not abandonment but respect.

Contact is framed as something that should serve the growth of both sides, not the ego of the dead. Ultimately, learning not to interfere is one of Liz’s key moral lessons, allowing her to step into her own life in Elsewhere without constantly trying to manage the world she left.

Second Chances, Forgiveness, and Moral Ambiguity

Second chances permeate Elsewhere, but they rarely arrive in neat or sentimental forms. The entire structure of backward aging and eventual Release constitutes a vast second chance built into the cosmos: everyone will live again.

However, this does not erase the harm, loss, or moral complexity of how they died. Curtis Jest, the rock star who died from heroin-related causes, finds in Elsewhere both a critique and a renewal.

His fame and self-destructive habits do not define him anymore; he can become a more grounded friend, animal advocate, and, eventually, Betty’s partner. Yet the consequences of his death—the grief of fans, the wasted potential—still exist.

Forgiveness in the novel is often delayed and difficult. Liz’s journey to understand and confront Amadou Bonamy exemplifies this.

She approaches him first as an abstract villain, an object for righteous anger. Watching his life reveals his kindness, responsibility, and love for his family, forcing her to reevaluate.

When they finally meet in Elsewhere, he is burdened by guilt and fear of judgment. Liz’s decision to tell him she forgave him long ago is less about absolving him cheaply and more about acknowledging that clinging to rage would imprison her as much as it would him.

Their interaction shows that forgiveness does not mean forgetting the wrong or pretending there were no consequences; it means choosing not to let that wrong define every future moment. Owen’s romantic storyline also engages with second chances.

His relationship with Liz is a new beginning after profound loss, yet when Emily arrives, he cannot simply discard that earlier bond. The narrative refuses to provide a clean resolution, instead portraying a gradual shift in which he and Emily adjust to their changed circumstances and he eventually allows himself to love Liz within the constraints of Elsewhere’s shrinking time.

Second chances here are always partial, always mixed with sorrow, and that complexity makes the moments of grace—Betty’s late-in-death romance, Alvy’s reunion with Liz’s voice, Liz’s peaceful Release—feel earned rather than automatic.

Work, Avocation, and Purpose

Work in Elsewhere is separated from economic survival and reframed as “avocation,” something one does for love rather than necessity. This redefinition allows the story to explore purpose without the usual pressures of bills, aging, and career ladders.

When Liz first arrives, she cannot see the point of working at all. There is no retirement to save for, no long-term accumulation of status or wealth.

Her skepticism echoes a common teen perspective: if the future you planned has vanished, why bother with anything? Aldous’s insistence that work is about joy rather than obligation sets the stage for Liz’s transformation.

At the Division of Domestic Animals, she discovers that she not only enjoys but excels at understanding animals’ needs and bridging communication between pets and humans. The satisfaction she gets from calming a nervous dog or guiding an adoption suggests that purpose can be found in caring for vulnerable beings, even when that care does not lead to prestige or long-term legacy.

Owen’s job at the Bureau of Supernatural Crime and Contact illustrates another facet of purposeful work. His role is born from his own failures at respecting the rules; he uses his hard-earned knowledge to prevent others from repeating his mistakes.

This gives his life in Elsewhere structure and meaning beyond personal relationships. Betty’s gardening and homemaking, Thandi’s broadcasting, Emily’s contemplation of becoming a keeper of books—all these roles contribute to a community where usefulness is separated from hierarchy.

The novel challenges the assumption that purpose must be tied to grand achievements or permanent outcomes. In a world where everyone will eventually forget and be reborn, the value of work lies in the present experience: the kindness offered, the beauty created, the skills practiced.

For Liz, embracing her avocation is a key step in accepting that her life in Elsewhere is not a waiting room but a real, worthwhile existence.

Memory, Forgetting, and Continuity of Self

Memory in Elsewhere is both a treasure and a source of pain. At first, Liz clings to memories of Earth as proof that her old life was real and important.

The Observation Decks function almost like a memory machine, allowing her to replay and extend scenes from her life by watching her family move forward without her. Yet this externalized memory keeps her emotionally stuck, unable to integrate what has happened.

The disappearance of her head stitches marks a crucial turning point: the last physical reminder of the accident vanishes, and with it goes a tangible link to Earth. Liz’s grief over the loss of the stitches shows how people sometimes hold on to scars, literal or symbolic, because they confirm the weight of past events.

Over time, as she grows younger, forgetting becomes inevitable. She and Owen slowly lose adult knowledge, reading skills, and even the context for their relationship.

The “game” of being older becomes just that—a game—and then fades entirely from her understanding. This might appear purely tragic, but the novel approaches it with a kind of gentle realism.

Forgetting is presented as part of the cycle that allows Release and rebirth; clinging forever to every memory would make that cycle impossible. At the same time, the story hints that something essential continues.

The baby born at the end is Liz and not Liz; she does not carry explicit memories, but the narrative encourages the sense that emotional patterns, capacities for love, and perhaps certain intuitions endure. Letters, keepsakes (like the gold watch), and messages in bottles act as anchors for those who remain older longer, preserving stories even as individuals regress.

Memory here is not an absolute record but a living, changing element of selfhood. The book suggests that people are not only their memories, yet what they remember, share, and eventually let go shapes the kind of life they are able to live, in Elsewhere and beyond.