Framed in Death Summary, Characters and Themes

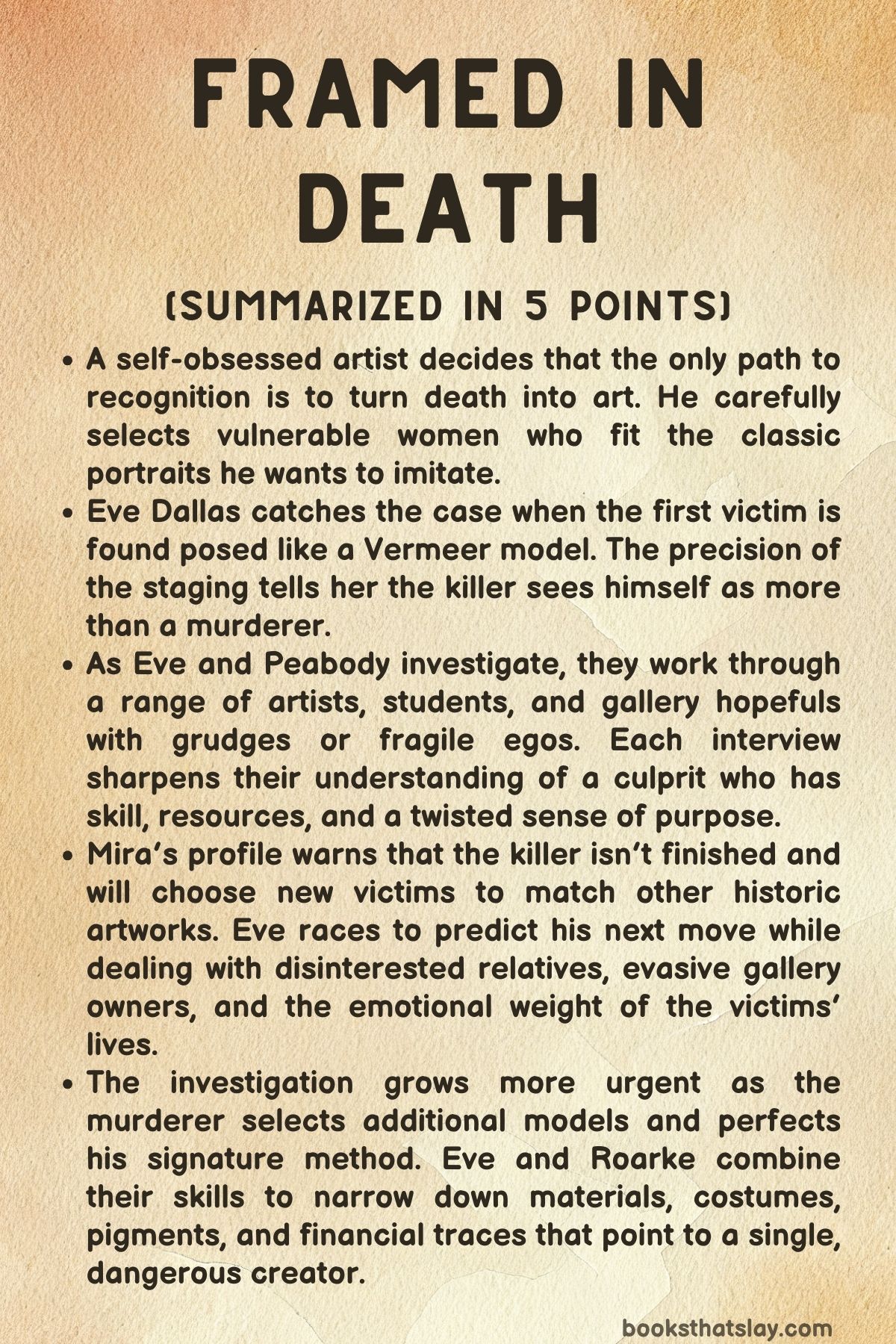

Framed in Death (In Death #61) by J.D. Robb is a crime thriller set in the near-future world of the In Death series, following NYPSD Lieutenant Eve Dallas as she hunts a murderer who believes killing is a legitimate path to artistic glory. The story explores the collision between ego, delusion, privilege, and justice.

When a young licensed companion is found arranged to resemble a classic painting, Eve discovers she is dealing with a killer who stages murder as “art.” As the bodies mount, Eve must confront a ruthless predator and an equally dangerous family determined to protect him—even at the cost of more lives.

Summary

A young licensed companion named Leesa Culver struggles to climb out of poverty, hoping to reach higher-paid status and escape her harsh life. Her determination draws the attention of Jonathan Harper Ebersole, a wealthy, self-absorbed painter convinced the world refuses to appreciate his brilliance.

Obsessed with the idea that great art must fuse life and death, he decides that murder is the missing element in his work. After months of meticulous preparation, he chooses Leesa solely because she fits the image he wants to recreate: a living replica of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring.

He lures her with an extravagant offer to model for him, leads her to his private building, and drugs and strangles her during the long posing session. He then fixes her body into the precise posture he wants, transports her in secret, and places her on a stoop in front of a family of art-gallery owners to ensure his “statement” is noticed.

Lieutenant Eve Dallas catches the case early the next morning. Leesa’s corpse is staged with uncanny precision, dressed in a hand-crafted replica of the painting’s costume.

Eve quickly recognizes the reference and brings in her husband, Roarke, whose knowledge of art helps confirm the match. Inside the Whittier home—chosen as the display site purely for symbolism—Eve interviews the family but finds no ties to the victim.

Their gallery connections, however, suggest the murderer may be someone who feels wronged or overlooked by the art world.

Eve digs into Leesa’s life and discovers a lonely young woman estranged from nearly all family members, with only an aunt willing to claim her body. The morgue report confirms she was drugged before being strangled, and the detailed staging leads Eve to believe the killer has considerable time, skill, and a deep fixation on classical art.

As Eve and Peabody investigate painters, students, and fringe creatives, they encounter a parade of temperamental artists—some angry, some insecure, some eccentric—but none with the combination of meticulous technique and psychological detachment the killer displays.

However, Dr. Mira’s profile clarifies the type of man Eve is hunting: an organized, intelligent, emotionally empty painter who sees people only as props. He will kill again, likely staging each murder as another interpretation of a famous work.

While Eve examines the art scene, Jonathan prepares for his next “masterpiece. ” He canvasses Times Square for a new “model,” eventually targeting Bobby Ren, an LC known for kindness and reliability.

Bobby disappears with a well-dressed man, and soon Jonathan kills again, posing Bobby in another replicated painting. Eve, after interviewing Bobby’s devastated friends and tracing his final movements, recognizes the pattern forming.

She and Roarke study Vermeer’s portraits, realizing Jonathan intends to create a series of deadly homages.

Jonathan escalates quickly. He scouts, selects, and murders a third victim, Chablis, posing her in an elaborate eighteenth-century costume.

His staging grows bolder and more theatrical, driven by his belief that he is finally achieving greatness. Eve’s investigation circles closer as she questions people who recall turning away a mediocre male painter obsessed with “adding life” to his work—feedback Jonathan twisted into justification for murder.

As evidence gathers, Roarke helps Eve locate suppliers of rare pigments and historically accurate costumes, leading them toward someone wealthy and deeply invested in authenticity. Eve begins to suspect an artist from privilege—someone with money, a private studio, and the time to plan each kill.

Eventually Eve and Roarke reach Jonathan’s residence, uncovering an astonishing amount of incriminating evidence: unfinished paintings, drug supplies, wigs, costumes, detailed research files, and an arrogant autobiography. Jonathan is arrested, but Eve fears the influence of his elite Harper family, particularly his powerful mother, Phoebe, who has spent years shielding him from consequences.

Her fears prove correct when Jonathan secures an expensive defense team and a judge grants him house arrest instead of remand. Eve knows he will try to run.

Working covertly with Roarke, she arranges surveillance and plants a hidden tracker. As expected, Jonathan and Phoebe attempt a carefully planned escape through an underground garage to a Harper-owned shuttle bound for a no-extradition zone.

Eve intercepts them at the private hangar with patrol units and media overhead. Jonathan panics and tries to flee; Eve stuns and arrests him on the tarmac.

Phoebe assaults Peabody attempting to protect her son but is taken into custody as well.

Back at Central, the tech Phoebe hired quickly confesses, revealing the lengths she went to in order to free her son: a new identity, offshore accounts, a villa, transportation, and an elaborate decoy plan. Jessup, the loyal bodyguard, refuses to talk, but it no longer matters.

Eve interrogates Jonathan, and when she and Peabody praise his “genius,” he cannot resist boasting. He confesses in gleeful detail, describing how he selected, drugged, posed, and killed his victims to bring “life” to his paintings.

With Jonathan fully exposed and legally sane, and Phoebe implicated as an accessory to murder and conspiracy to commit further killings, Eve’s work reaches its conclusion. The murderer is headed to an off-planet maximum-security prison, his mother destined to live out her remaining years behind bars.

For Eve Dallas, justice is served, the case is closed, and the victims’ voices can finally rest.

Characters

Jonathan Harper Ebersole

Jonathan Harper Ebersole is the chilling engine powering the narrative of Framed in Death. A narcissist with a grandiose sense of destiny, he is convinced that the world has failed to recognize his “true genius.” This delusion becomes the foundation of his murderous philosophy: that only by merging death with art can he create works worthy of immortality. Jonathan is methodical, patient, and calculating, capable of creating a façade of shyness and awkward charm to lure his victims.

His ability to maintain a calm exterior while harboring violent fantasies underscores the depth of his psychopathy. He does not view his victims as people, but as “subjects,” aesthetic elements to be used, arranged, and discarded.

His obsession with the techniques and symbolism of classical art reveals both his aspiration and his insecurity; he imitates masterpieces because he lacks originality of his own. Even when arrested, Jonathan’s arrogance persists—his pride in his “art” ultimately becomes his downfall when he cannot resist confessing.

Jonathan represents the terrifying combination of privilege, delusion, and emotional emptiness.

Eve Dallas

Eve Dallas stands as Jonathan’s antithesis—a homicide cop defined by duty, grit, and moral clarity. She approaches each case with relentless determination, refusing to allow emotional distance to harden her compassion for the victims.

Eve is sharp, observant, and intuitive; she reads crime scenes as if they speak directly to her. While her background is marked by trauma, she channels her past into her commitment to justice.

Her subtle emotional arc in the story reveals her ongoing struggle to balance vulnerability with strength, relying on Roarke and her team while fiercely guarding her independence. Eve’s leadership is marked by her straightforward communication, her insistence on integrity, and her ability to command respect from those around her.

Her pursuit of Jonathan becomes not just a professional obligation but a moral imperative, as she recognizes early on that he will kill again. Eve’s drive, intelligence, and capacity for deep empathy make her the grounding force of the narrative.

Roarke

Roarke serves as Eve’s partner in every sense—emotionally, intellectually, and practically. His vast resources, technological expertise, and deep knowledge of art become invaluable in the investigation.

Roarke is suave, charming, and composed, yet fiercely protective of Eve. His reactions to Jonathan’s so-called art—disgust, rage, and disdain—underscore his refined aesthetic sense and his strong moral center.

Despite his polished exterior, Roarke retains an undercurrent of streetwise instinct and a readiness to act decisively when needed. In the narrative, he provides a stabilizing presence for Eve, reminding her she is not alone, grounding her emotionally, and helping her navigate the darker moments of the case.

Their partnership also highlights a contrast: Roarke’s ability to move fluidly through high-society circles becomes a tool Eve relies on, demonstrating how seamlessly they complement each other.

Leesa Culver

Leesa Culver is the first victim we meet, and though she appears only through memories and evidence, she is far more than a nameless casualty. Her life is marked by struggle and isolation, with little family support and relentless effort to rise within her profession.

Despite her circumstances, she is disciplined, ambitious, and determined to escape poverty. The scattered cash in her apartment, the absence of personal connections, and her singular focus on financial stability reveal a young woman trying desperately to build a better future.

Her vulnerability is not weakness; it is the tragic result of her environment and lack of support. Leesa’s death underscores the cruelty of Jonathan’s worldview—he chooses her not for anything she has done, but because she fits his aesthetic fantasy.

Through Eve’s empathy and Carmen Young’s unexpected compassion, Leesa is given dignity in death that she was rarely afforded in life.

Phoebe Harper

Phoebe Harper emerges as a villain parallel to her son—sculpted not by delusion but by entitlement and cold calculation. She embodies the ruthless elitism of her powerful family, treating the legal system as an inconvenience rather than an authority.

Phoebe’s instinct is control: of her image, her son’s fate, and anyone she deems beneath her. The extent of her involvement in Jonathan’s crimes—knowingly aiding a serial killer, financing his escape, arranging false documents—reveals both her moral bankruptcy and her unwavering belief that the world should bend to her will.

Her fierce maternal loyalty is warped into something monstrous: she values Jonathan’s freedom more than the lives he has taken. When she finally loses control and strikes Eve, the façade cracks, exposing the fury beneath her icy composure.

Phoebe is not merely an accessory; she is a reflection of the privilege and indulgence that helped shape Jonathan into a killer.

Peabody

Detective Delia Peabody brings warmth, humor, and grounded practicality to the investigation. She balances Eve’s intensity with loyalty and emotional intelligence, often smoothing interpersonal friction and offering perspective.

Peabody’s growth as an investigator is evident in her meticulous handling of evidence, her intuitive reads on suspects, and her confidence in the field. Her relationship with McNab and her close bond with Eve provide moments of levity and heart, illustrating the family that can form among cops under pressure.

Peabody’s steady presence anchors the investigation, and her resilience is a quiet but constant force.

Dr. Charlotte Mira

Dr. Charlotte Mira, the NYPSD’s top profiler, provides the psychological lens through which Eve interprets Jonathan’s behavior.

Calm, compassionate, and analytical, Mira brings a clinical clarity to the case. Her profile of Jonathan—organized, methodical, obsessive—helps Eve anticipate his next moves and understand his motivations.

Mira also offers Eva a kind of emotional counsel, often helping her process the darkest aspects of her work. Her ability to blend scientific insight with empathy makes her indispensable in cases involving deviant psychology.

Mira’s soft-spoken demeanor contrasts sharply with the horror she dissects, emphasizing the strength required to confront monstrosity with kindness and intellect.

Fiona Whittier

Fiona Whittier is a secondary but emotionally resonant character, a rebellious teen whose night out leads her to discover Leesa’s body. Her reactions to the crime reveal her vulnerability beneath her tough exterior.

Fiona’s family dynamic—strained, artistic, and chaotic—adds texture to the investigation, showing how ordinary people are pulled into the orbit of violence. Though not central to the plot, Fiona embodies the shock and confusion of an innocent person thrust into a nightmare, reminding the reader of the wider impact of Jonathan’s crimes.

Themes

Obsession with Artistic Immortality

Jonathan’s fixation on greatness forms the core of Framed in Death and exposes how the desire for recognition can mutate into destructive self-worship when paired with entitlement and emotional detachment. His worldview centers on the belief that the world has treated him unfairly, that critics are blind, and that genuine genius—his genius—must be proven through extraordinary acts.

Instead of accepting that talent requires discipline, feedback, and humility, Jonathan constructs a fantasy in which he is persecuted by mediocrity. This delusion allows him to justify murder as a legitimate extension of artistic creation.

He turns revered art into a blueprint for violence, believing that death will give his work the vitality he lacks as an artist. His obsession is not about art itself but about being admired, worshipped, and immortalized.

Each victim becomes an object to be “arranged,” a tool to reinforce his imagined brilliance. He treats life as raw material and murder as a signature style.

The more he indulges this belief, the more confident and reckless he becomes—seeking increasingly elaborate recreations, investing in costumes, pigments, staging, and research, all while convincing himself that the universe finally recognizes him. His vanity blinds him to the mediocrity of his own work; Roarke’s fury at the paintings highlights the tragic absurdity of Jonathan’s quest.

His crimes are gruesome, but they are also fundamentally pathetic: every killing is a desperate attempt to force the world into validating a talent he does not possess. The novel uses his obsession to illustrate how self-delusion, when mixed with privilege and sociopathy, becomes a force capable of annihilating anyone unfortunate enough to fall into its path.

The Dehumanization of Vulnerable Women

The victims in the story are young, economically insecure women whose marginalization makes them easy targets for Jonathan’s predatory attention. Their profession exposes them to constant risk, and the societal neglect surrounding them creates the perfect conditions for a predator who requires anonymity and pliability.

Jonathan does not view them as individuals with histories, fears, or aspirations; he selects them purely for their physical likeness to the women in the paintings he seeks to copy. By reducing living human beings to props, he strips them of identity before he even harms them.

The staging of their bodies, the manipulation of their limbs, the gluing and wiring of their forms, and the use of their corpses as components of a composition all reinforce his belief that they exist for his benefit. Leesa’s lonely apartment, her estrangement from family, and her relentless drive to reach a higher LC level underscore how isolation can render a person invisible until tragedy brings attention.

Chablis and Bobby, likewise, are vulnerable because society has already decided they are peripheral. Eve’s response stands in deliberate contrast to this dehumanization.

She insists on giving victims dignity—learning their names, contacting relatives, providing closure, and demanding justice with an intensity that counters the indifference they experienced in life. The theme exposes the hierarchy of value society assigns to human lives and challenges it at every turn.

In showing the stark difference between Jonathan’s objectification and Eve’s unwavering recognition of each victim’s humanity, the narrative emphasizes that justice begins with seeing someone as a person rather than a disposable form.

Power, Control, and the Performance of Violence

Jonathan’s murders are not impulsive acts but meticulously orchestrated displays of dominance. His need for control permeates every aspect of the killings: the sedatives that render victims powerless, the hands around their throats, the unhurried staging afterward, and the calculated public placement of their bodies.

For him, the killing itself becomes a ritual that reassures him of his superiority. The ability to decide the moment of death feeds an ego that cannot be satisfied by creativity alone.

Control also defines his interactions with his mother, Phoebe, whose own need to shape outcomes mirrors his. Her interventions—arranging escape routes, hiring specialists, funding evasion—reflect a lifelong pattern of enabling and managing Jonathan’s failures.

She refuses to let the world hold him accountable because doing so would dismantle the image she has constructed of their family’s perfection. In this sense, the theme extends beyond the murders; it appears in parental manipulation, in wealth used as a shield, and in the casual assumption that consequences apply only to others.

Eve represents the opposing force: someone who reclaims control through investigation, procedure, and truth. Her pursuit strips away Jonathan’s illusions, Phoebe’s strategies, and the Harper family’s influence.

The contrast illustrates the central conflict between control built on violence and deception, and control built on responsibility and accountability. The story ultimately argues that power without empathy corrodes judgment until nothing remains but self-serving brutality masquerading as purpose.

Privilege, Wealth, and the Manipulation of Justice

Jonathan and Phoebe operate within a sphere where money shapes outcomes, where elite connections shield wrongdoing, and where the justice system can be bent if one is determined and ruthless enough. Jonathan’s entire lifestyle—his studio, his custom materials, his secure residences, his ability to disappear bodies without immediate suspicion—is funded by generational wealth that insulates him from the realities his victims face daily.

Phoebe’s behavior exposes the darker side of privilege: the conviction that laws are negotiable, that judges can be swayed, and that justice is an obstacle rather than a principle. She treats Jonathan’s murders as inconveniences to be managed rather than atrocities requiring accountability.

Her attempt to replace the court monitor, arrange new identities, and secure a villa abroad reveals an ingrained belief that consequences simply do not apply to people of her status. The courtroom granting house arrest reinforces how the wealthy can exploit procedural loopholes unavailable to ordinary defendants.

Yet the narrative counters this privilege through Eve’s strategic planning, Roarke’s behind-the-scenes support, and the eventual exposure of the Harper family’s schemes. The takedown at the shuttle hangar—public, undeniable, televised—symbolizes the collapse of a system the Harpers believed they controlled.

By showing how privilege can enable violence, obstruct truth, and protect killers, the novel illuminates the ongoing struggle to ensure justice is not determined by the weight of a bank account but by the weight of evidence and moral responsibility.

Found Family, Loyalty, and Emotional Restoration

Amid the darkness of the investigation, the story repeatedly highlights the grounding force of chosen connections. Eve’s circle—Roarke, Peabody, McNab, Mavis, Leonardo, Bella, and even Summerset—forms a counterbalance to the isolation and emotional sterility that define Jonathan’s life.

Their loyalty is not blind but earned through shared battles, mutual respect, and everyday gestures of care. Eve’s exhaustion after crime scenes, her flashes of humor, her stress over paperwork, and her moments of vulnerability all find relief within this network.

The housewarming party, the walk with wine, the shared meals, and the easy banter reinforce that support systems are essential for those who confront human cruelty on a daily basis. These connections do not simply offer comfort—they strengthen Eve’s resolve, keep her grounded, and remind her of the value of life in a world shadowed by violence.

Jonathan, in contrast, exists within a hollow structure built by privilege but devoid of genuine affection. Phoebe’s devotion is performative and rooted in image rather than empathy.

Their relationship is built on denial, manipulation, and enabling, producing a man who cannot form authentic bonds. The stark difference between Eve’s found family and Jonathan’s toxic legacy underscores how real loyalty nurtures resilience, while distorted loyalty amplifies destruction.

The theme demonstrates that justice is not pursued in isolation; it is sustained by the emotional bonds that remind characters what they are fighting to protect.