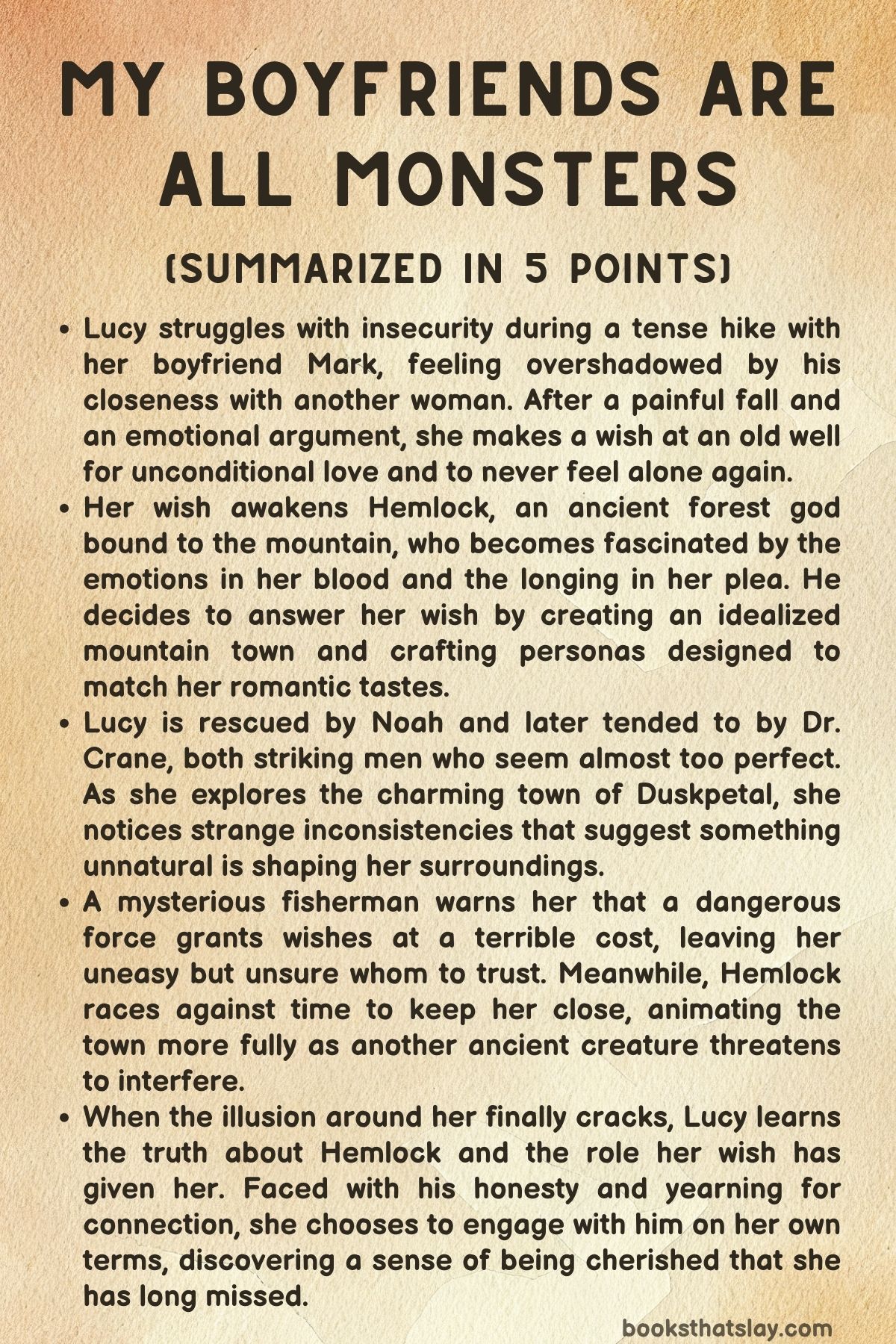

My Boyfriends Are All Monsters Summary, Characters and Themes

My Boyfriends Are All Monsters by Kimberly Lemming is a romantic fantasy about longing, self-worth, and unexpected devotion. The story follows Lucy, a young woman who feels overlooked and unimportant in her relationship and among her friends.

A single impulsive wish on a lonely mountainside leads her into the world of an ancient forest god who has been waiting centuries for someone to call on him. What begins as a strange misadventure becomes a journey where Lucy discovers affection, desire, and a sense of belonging she never knew she could claim. The book blends humor, romance, and supernatural charm into an adventure that is warm, bold, and deeply character-driven.

Summary

Lucy joins her boyfriend Mark and their friends on a mountain hike, already uneasy about how closely Mark acts with Stephanie. Her insecurities deepen when she injures her leg on the trail.

The blood dripping into the soil awakens an ancient forest god bound to the mountain. Through the senses of a raven, he observes Lucy and tastes the emotional turmoil carried in her blood.

What he feels is jealousy, embarrassment, and a quiet longing to be valued. These feelings stir something old inside him, and he starts paying attention.

After an argument with Mark—who chooses to continue the hike without her—Lucy calls her friend Jess to vent while wandering off the trail. She finds an overgrown stone well tucked away beneath vines and moss.

Feeling foolish and unwanted, she tosses a coin inside and makes a simple wish: to be loved without conditions and never feel alone again. The god hears this as a direct offering.

The coin restores some of his dormant power and recalls memories of his lost worship. He decides that Lucy must be his new Priestess and that he will grant the wish she has unknowingly given him responsibility for.

Lucy tries to return to the trail, but a heavy fog sweeps across the mountainside. Strange noises follow, and before she finds her bearings, a rockslide crashes down the slope.

She injures her ankle and is stranded until a beautiful, long-haired man named Noah arrives with a white horse and a group of alpacas. He brings her to a charming little mountain town called Duskpetal, which seems pulled from a storybook with its brick storefronts, festival decorations, and inviting streets.

There she meets Ansel, a friendly baker, and Dr. Crane, a stern but attractive physician who tends to her ankle.

They inform her that falling rocks have blocked the only road up or down, trapping her until repairs are made. What Lucy doesn’t know is that these people and the entire town are creations designed by the god—Hemlock—who crafted them from her preferences, gathered from scattered romance novels and magazines left by past victims.

Noah and Crane are shaped to appeal to her specific tastes.

Hemlock’s work is interrupted by another immortal being, Shriek, a sly creature who rules over nearby mist-filled valleys. Shriek mocks Hemlock for claiming a new maiden and teases him about the three-day limit on fulfilling a wish.

If Hemlock fails, Lucy’s soul becomes vulnerable to other entities. Shriek adds that he has already crossed paths with her and could take her if Hemlock falters.

Worried, Hemlock rushes to strengthen his illusion of Duskpetal, filling it with lively details and handsome townsfolk to keep Lucy engaged and content.

Lucy wakes the next morning to an almost empty town. The inn seems deserted.

Shops appear unattended. She finds no nurse at the clinic.

Confused, she explores and takes a photo of delicate white flowers outside a candy shop. From the trees nearby, a strange fisherman calls out to her, warning that she is a petitioner who has made an offering to something dangerous.

He urges her to escape before “old thorns” returns. When he reaches out to guide her, she refuses.

Dr. Crane appears moments later and scolds her for walking on her injured ankle.

The fisherman is gone without a trace.

Back at the inn, the elderly owner Caroline abruptly hands Lucy the keys and deed to the place, insisting that it now belongs to her. Crane carries Lucy upstairs, treats her ankle, and shares a moment with her that nearly becomes romantic before Noah interrupts with food and yet another gift of property.

Overwhelmed, Lucy showers, rests, and finally breaks up with Mark through a text message.

When she looks out her window after the call, the once-empty town is now bustling with people, dogs, and activity. She calls Jess and describes what is happening.

Jess identifies the flower Lucy photographed as poison hemlock. When Lucy repeats the word aloud, the entire town freezes and turns toward her at the same time.

Lamps shift into tree leaves, buildings flicker, and unsettling cracks appear in the illusion. Crane tries to calm her, but Lucy demands answers.

Hemlock withdraws from his other avatars and pours his consciousness fully into Crane’s body, expanding it with wings to contain his presence. He reveals the truth: he is the god of the mountain, the keeper of illusions, and her coin bound them together.

He insists he means no harm, that he wants only to grant her wish for love and free her from the loneliness that mirrors his own ancient isolation.

Lucy questions the nature of this bond and whether she has agency. In response, Hemlock reshapes himself into a form drawn from her jokes about romance novels—part man, part massive kraken-like creature with a broad torso and graceful tentacles.

The transformation shows he is willing to change rather than control. Moved by his honesty, and tired of feeling like a second choice in her human relationships, Lucy reaches for him.

They share an intimate and supernatural encounter that seals their connection.

Afterward, Lucy reassures her friends by phone and reflects on the strange comfort she feels in Duskpetal. Hemlock asks her to remain with him permanently.

He promises to build any life she wants, give her companionship, and worship her for the rest of his existence if she will share her warmth and ease his loneliness. Lucy, who has long felt overlooked, finally believes someone truly sees her.

She accepts his offer and chooses to stay. As she jokes that he won her over with free real estate, she embraces her place as Hemlock’s Priestess and partner, ready to start a new life in his enchanted mountain town.

Characters

Lucy

Lucy is the emotional core of My boyfriends are all monsters, a woman whose insecurities, desires, and longing for unconditional affection shape the entire narrative. She begins the story feeling overshadowed in her own relationship, nursing quiet jealousy and the persistent ache of inadequacy.

Her slip on the mountain—both literal and emotional—exposes just how invisible she feels, especially when Mark abandons her during the hike. The depth of her self-doubt becomes the very thing that draws Hemlock’s attention when he tastes her blood: she is a well of conflicted emotion he has not encountered in ages.

Despite her insecurities, Lucy is empathetic, curious, and resilient. She pushes through physical pain and confusing circumstances with a blend of stubbornness and vulnerability.

Her wish at the well is not born out of selfishness but from a lifetime of feeling like an afterthought. Throughout her time in Duskpetal, she moves from confusion to suspicion to empowerment as she confronts the illusions surrounding her and the god manipulating them.

By the end, Lucy recognizes her own worth, realizing that she deserves a love that chooses her openly and enthusiastically. Her decision to stay with Hemlock is not a surrender but a reclamation: she chooses a life where she is wanted, cherished, and central.

Hemlock

Hemlock, the ancient forest god bound to the mountain, is a being shaped by millennia of solitude and fading worship. Through the raven’s eyes, he surveys the modern world with a mixture of detachment and forgotten longing.

Lucy’s blood and her wish reignite a spark within him—both power and purpose—leading him to construct an entire town, population, and identities tailored to her tastes. This act illustrates both his immense power and his emotional fragility; he is godly not in morality but in scale, driven by yearning and possessiveness more than malevolence.

Hemlock is fundamentally lonely, desperate for connection yet inexperienced in boundaries. His attempts to please Lucy—shifting forms based on romance novels, creating idyllic settings, and offering devotion—reveal a deep desire to be understood and accepted.

Despite his manipulative displays and the eerie coordination of his avatars, he is not cruel. Instead, he is sincere in his hunger for companionship and frightened of losing the soul he feels destined for.

When he finally reveals himself fully, he approaches Lucy with reverence rather than force, offering her a choice even though it pains him. His blend of monstrous forms and tender devotion makes him a symbol of embracing the strange and finding love beyond the expected.

Mark

Mark represents the kind of quiet emotional neglect that shapes much of Lucy’s insecurity. Outwardly harmless and seemingly reasonable, he repeatedly prioritizes other people—particularly Stephanie—over Lucy, undermining her confidence in subtle yet damaging ways.

His decision to leave her behind on the trail while she is hurt encapsulates his disregard; he sees her feelings as inconveniences rather than expressions of vulnerability.

Though he is not villainous, Mark embodies mediocrity masked as stability.

His role in the story is to highlight the contrast between being tolerated and being cherished. His presence haunts the early parts of Lucy’s journey, reinforcing how deeply she craves to be chosen.

When she ultimately breaks up with him, it signals her first act of true self-respect, paving the way for her union with Hemlock.

Noah

Noah is the first avatar Lucy encounters, a charming, pastoral figure crafted to appeal to her romantic sensibilities. With his white horse, alpacas, and gentle demeanor, he arrives as a literal rescuer—an embodiment of a fairy-tale hero.

His existence reflects Hemlock’s understanding of the tropes Lucy finds comforting: rugged beauty, kindness, and a hint of mythical charm.

Yet Noah is not fully real.

His actions are guided by the god animating him, his personality shaped by Hemlock’s need to make Lucy feel safe and wanted. Even so, Noah serves a thematic purpose: he introduces Lucy to the dreamlike unreality of Duskpetal, easing her transition from the mundane world to one woven out of desire and illusion.

He symbolizes warmth and fantasy, a crafted contrast to Mark’s indifference.

Dr. Crane

Dr. Crane functions as Hemlock’s primary avatar and later becomes the vessel for Hemlock’s true manifestation.

As the gruff, competent doctor archetype, he is designed to appeal to Lucy’s deeper, more mature romantic preferences. His brusque concern, his careful tending of her injury, and the almost-kiss they share make him both protective and tantalizing.

Once Hemlock concentrates his essence into Crane, this form becomes the bridge between god and woman. Crane’s body absorbs wings, shifting details, and eventually monstrous features as Hemlock reveals his many layers.

Through Crane, Hemlock expresses his vulnerability, his reverence, and his desire for Lucy’s companionship. The fusion of physical beauty and supernatural strangeness underscores the theme of embracing love that defies normal boundaries.

Shriek

Shriek, the opossum trickster god, is a chaotic presence who serves as a foil to Hemlock. Where Hemlock is heavy with longing and nostalgia, Shriek delights in mischief, biting commentary, and opportunism.

His arrival introduces the danger and unpredictability of the supernatural world surrounding the mountain.

Shriek’s taunting reminds Hemlock of the rules governing wishes and souls, injecting urgency into the narrative.

He also acts as a warning: ancient beings are not bound by human morality, and Lucy’s involvement with them carries real risk. Despite his sharp humor, Shriek represents the predatory side of magic—unpredictable, hungry, and amused by human vulnerability.

Jess

Jess is Lucy’s tether to the real world and the embodiment of a supportive friend. Through phone calls and texts, she provides grounding, perspective, and emotional reinforcement.

Jess listens without judgment, encourages Lucy to stand up for herself, and offers genuine concern even when she cannot physically be present.

Her identification of the poison hemlock and her steady presence help Lucy piece together the oddities surrounding Duskpetal.

Jess symbolizes the friendships that nourish rather than drain, and her unwavering support contrasts with Mark’s dismissiveness. Even from afar, she helps Lucy choose a future where she feels valued.

Caroline

Caroline is the inn owner whose abrupt departure and sudden gifting of the property reveal the uncanny nature of the town. Her behavior is kind yet unsettling, as though she is acting out a script written moments before.

She embodies the artificial warmth of Duskpetal, a figure designed to offer Lucy security, domestic charm, and the promise of belonging.

Her role emphasizes the illusionary nature of the town and hints at Hemlock’s desire to fulfill every facet of Lucy’s wish, even if it means creating people whose motivations begin and end with her happiness.

Caroline represents comfort wrapped in eeriness—a reminder that the kindness surrounding Lucy is not entirely human.

Themes

Self-Worth and the Desire to Be Chosen

Lucy’s emotional landscape is defined by a quiet ache that has been present long before she enters the mountain. Her relationship with Mark—marked by indifference, subtle dismissals, and the feeling of being an afterthought—reinforces a belief that she is someone people tolerate rather than cherish.

The story builds this internal conflict through her reactions: the sting she feels when Mark walks ahead with Stephanie, the embarrassment after she cuts her leg, and the shame she carries when she calls her friend to vent. Her wish at the well is not born from greed or vanity but from exhaustion.

She wants the simple comfort of being someone’s first choice, the assurance that love is not conditional on perfection, flawless confidence, or social performance. As the narrative unfolds, this desire becomes the axis around which everything turns.

Hemlock’s fixation on her—his need for her presence—acts as both wish fulfillment and confrontation. Lucy must grapple with the sudden shift from feeling overlooked to being adored with overwhelming devotion.

The theme explores how deeply the longing for validation can shape a person’s decisions, especially when that validation finally arrives in a form both comforting and frightening. Her journey becomes a negotiation between being wanted and learning that being chosen does not have to be the result of desperate wishing; it can emerge from recognizing her own value.

By the end, her acceptance of Hemlock is not a surrender to fantasy but a moment of recognizing that she deserves to be met with eagerness, not indifference.

Power, Vulnerability, and Unequal Exchanges

The relationship between Lucy and Hemlock is built on an inherent imbalance: one is a mortal woman with a twisted ankle and a history of neglected feelings, and the other is an ancient god whose influence shapes landscapes, avatars, and illusions. The story does not shy away from the tension that arises when affection crosses such a gap.

Hemlock’s ability to design entire personalities, physical forms, and environments to appeal to Lucy raises questions about authenticity and consent. Even his desire to keep her close, motivated by millennia of loneliness, carries shades of possessiveness that could easily tip into coercion.

Yet the narrative carefully explores how vulnerability operates on both sides. Lucy’s vulnerability comes from emotional wounds; Hemlock’s from a cosmic solitude that has hollowed him out over centuries.

He may have immense power, but his fear of losing Lucy makes him hesitant, attentive, and almost desperate to reassure her. Their bond grows from this mutual exposure.

Lucy does not accept him because he overwhelms her, but because he listens, adapts, and shows a willingness to give her space despite his longing. The theme also examines how power transforms when mixed with affection.

Hemlock’s abilities become tools not for domination but for expression—wanting to be seen, wanting to be enough. The dynamic challenges the traditional structure of god–human relationships by portraying power not as a weapon but as something softened by emotional need.

However, the story keeps the reader aware that this balance is fragile, making their final union feel earned rather than predetermined.

Illusion, Reality, and the Construction of Desire

Duskpetal itself is a reflection of Lucy’s inner wishes: a place filled with autumn warmth, picturesque storefronts, attentive caretakers, and handsome strangers designed from the echoes of her preferred romances. The town functions as a mirror for the fantasies people often use to escape their ordinary disappointments.

Hemlock constructs this environment not out of malice but as an attempt to craft the version of happiness Lucy seeks, drawing from discarded magazines and novels as his instruction manuals. The eerie empty streets, the sudden appearance of townsfolk, the transformation of lamps into leaves—these shifts highlight how fragile the construct is.

Beneath the charming setting lies a reminder that comfort built from illusions can collapse with a single word. Lucy’s journey through the town forces her to confront what she truly wants: not a perfect fantasy, not a curated romance, but a connection that feels real even when wrapped in supernatural elements.

Hemlock’s ability to change his form, create new faces, and reshape the environment underscores the theme that desire can be influenced, encouraged, or framed, but ultimately must be chosen with clear eyes. By stepping toward him after learning the truth, Lucy distinguishes between manipulated longing and genuine affection.

The theme centers on the human tendency to idealize love and how the line between fantasy and sincerity becomes meaningful only when someone chooses reality, even when reality includes a powerful, winged god offering a life built from shapeshifted devotion.

Loneliness, Companionship, and the Fear of Abandonment

Both Lucy and Hemlock carry a profound fear of being left behind. Lucy’s loneliness stems from social dynamics, strained relationships, and the repeated feeling that she must work to earn her place in someone’s life.

Her wish—to never be alone again—is rooted in years of believing that companionship is fragile, easily taken, and dependent on others finding her useful. Hemlock’s loneliness is older and more immense, tied to centuries of abandonment as human worship dwindled.

His desperation to keep Lucy safe, his panic when Shriek threatens to interfere, and his meticulous crafting of Duskpetal reflect a being terrified of losing the first meaningful bond he has had in ages. Their connection becomes a meeting point between two forms of isolation: one human and one divine.

The theme examines how companionship can emerge from mutual recognition rather than perfect circumstances. It also highlights how fear can motivate acts of kindness, overprotection, or vulnerability.

Lucy’s decision to stay is not a capitulation to Hemlock’s fear, but a moment where she acknowledges her own. Neither of them wants to continue existing in a world where affection is uncertain or temporary.

Their partnership becomes a remedy for this shared ache, suggesting that chosen companionship—born from honesty, understanding, and reciprocal desire—can soothe even the deepest forms of solitude.