Hot Wax Summary, Characters and Themes

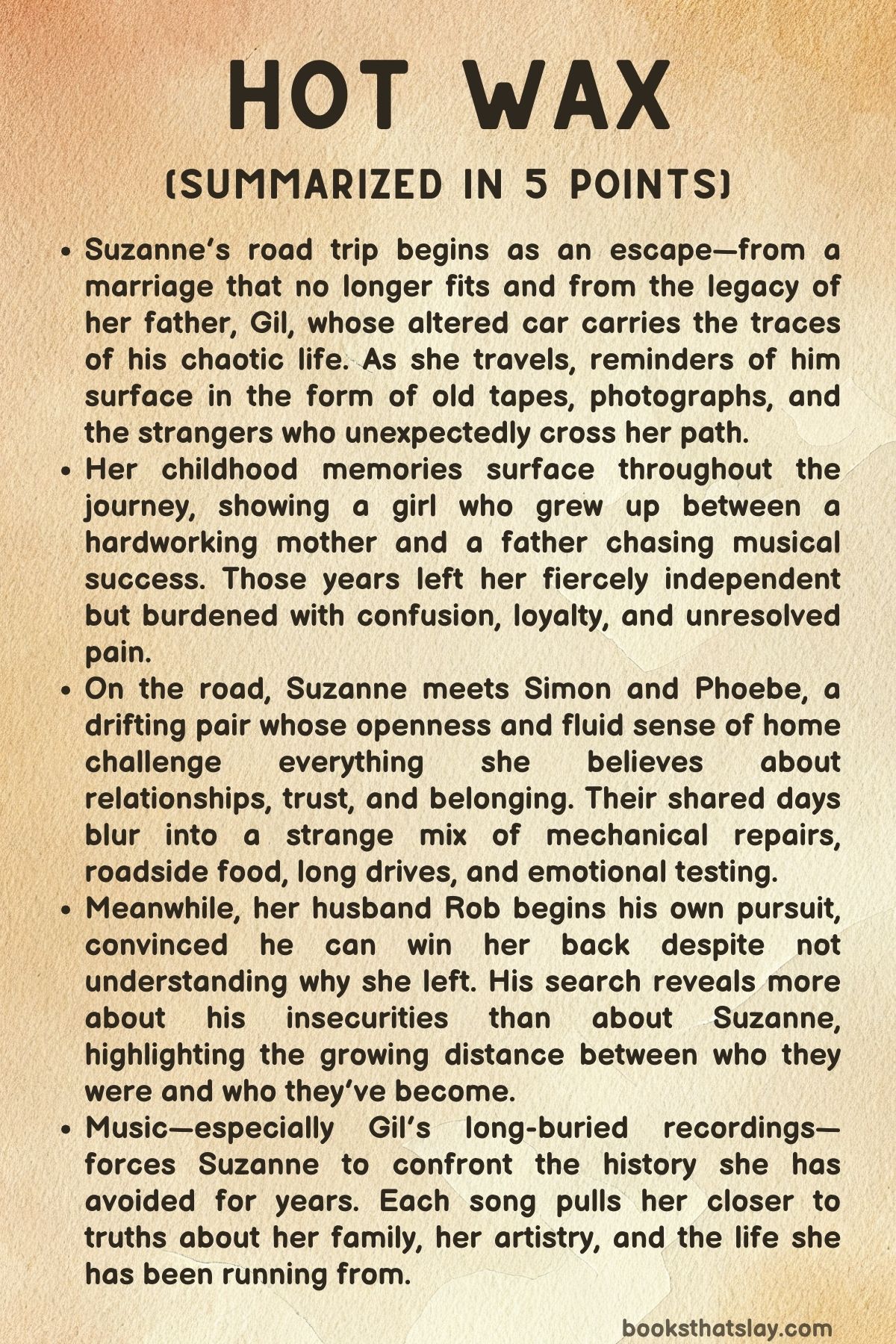

Hot Wax by ML Rio is a story about memory, escape, and the long shadow of a chaotic childhood. It follows Suzanne Delgado, a woman shaped by a childhood spent chasing the unstable dreams of her rock-musician father, Gil.

Now an adult drifting through a stalled marriage and an unresolved past, Suzanne sets off on a road trip in her late father’s strange, booby-trapped car. Along the way she confronts old wounds, unexpected companionship, and the ghosts of a life she never fully understood. The novel moves between past and present, showing how a single upbringing can fracture a person’s identity for decades.

Summary

Hot Wax follows Suzanne Delgado, a woman escaping Miami in her late father Gil’s heavily modified 1968 Ranchero, a bizarre machine filled with stage props, old equipment, hidden compartments, and taped messages that catch her off guard. Exhausted and driving through the night, she hits a switch that triggers a recording of Gil singing, and the surge of emotion distracts her enough to send the car into the swampy roadside.

Rummaging through the glove box afterward, she finds her childhood atlas, marked with crayon trails from the tours she once followed, especially the bold red line leading west toward Las Vegas. This discovery pushes her toward a confrontation with her past.

The story moves back to Suzanne’s childhood in Baltimore during the late 1980s. Her mother, Nora, works endlessly to keep them afloat while Gil tours with his band, chasing stardom.

Suzanne grows up surrounded by arguments she only partly hears, cramped rowhouses, and long afternoons spent alone. Nora teaches her how to navigate bus routes so she can stay safe, and Suzanne builds a life of independence at the South Fork Mall.

She gravitates to Most Wanted, the record store where she studies albums, saves money for a Polaroid camera, and begins capturing the world in photographs.

Her routine shifts when she spots Nora laughing intimately with a stranger at Macy’s. Disturbed, she wanders into Most Wanted after closing.

Doug, the clerk, lets her stay if she helps him with price tags. She keeps returning, learning how to spot shoplifters and becoming Doug’s unofficial assistant.

She uses the money she earns to buy tapes she hides at home, listening late at night because Nora bans daytime music due to thin walls and nosy neighbors.

Gil eventually returns from a long tour and picks Suzanne up at the mall. Their reunion is warm but strained; Suzanne resents his long absences, and Gil tries to promise improvement.

When they reach the apartment, they find it wrecked. Nora has torn apart Suzanne’s secret cassette stash, convinced the items were stolen.

A terrifying fight explodes between Gil and Nora, neither listening to Suzanne’s repeated protests. Nora strikes Suzanne, who hides in the linen closet until morning.

By then, Gil has vanished again without saying goodbye.

Back in the present, Suzanne is stuck at the Sundew Value Inn while multiple mechanics fail to repair the Ranchero. A young drifter named Simon offers to fix it if he can hitch his trailer to the car and ride as far as Georgia.

Suzanne reluctantly agrees. His partner, Phoebe, soon appears, sharp and curious, rummaging through Gil’s odd belongings.

She recognizes the value of old CDs and hints that she and Simon trade secondhand goods to survive. Suzanne retreats into a packet of old Polaroids, photographs from her last summer with Gil and his band, including an image of Gil and Nora the night they met.

She studies these pictures as she gathers strength to face memories she has long avoided.

Suzanne then experiences a brief life in the Panhandle with Simon and Phoebe while the car is in pieces. They live out of an Airstream trailer crowded with vintage clothes, flea-market finds, and random treasures Phoebe sells.

Suzanne feels out of place around their relaxed confidence and constant reinvention. A trip to a consignment shop prompts her to finally turn her phone on after days of silence; she sees messages from her husband, Rob, along with royalty deposits from Gil’s music.

She calls Rob only to leave a short message saying she is leaving for good, that he can keep everything, and that their marriage is finished.

In Washington, DC, Rob tries to understand the voicemail. Encouraged by his brothers, he decides to chase her rather than accept the breakup.

Meanwhile, Suzanne and Simon spend an afternoon test-driving the newly repaired Ranchero. A playful moment in a drive-in parking lot almost becomes something more, but Suzanne stops it.

Back at the motel, Phoebe pieces together what happened and calmly explains that she and Simon share an open relationship. She tells Suzanne there is room for her too, if she wants it.

Rob, determined to win Suzanne back, sells their Prius, buys a used pickup, digs through her studio, and finds a note he interprets as a lead toward Tampa. He begins following her trail south.

Flashbacks deepen Suzanne’s memories of touring with Gil. At one point, Nora marries a man named Nathan, and during their honeymoon, Gil and his girlfriend Gracie take Suzanne on tour.

Suzanne meets the band in grungy backstage rooms and becomes part of the crew, documenting everything with her Polaroid. The Kills begin gaining fame, but tension builds, particularly around Skelly, the guitarist who becomes a protective figure to Suzanne.

A major turning point arrives in Nebraska, where the band plays a disastrous show in an airplane hangar packed with drunk, hostile locals. Gil provokes the crowd with one of their most controversial songs.

Violence erupts; a bottle hits Gil, Suzanne falls from the sound booth and is trampled, and Skelly attacks the man responsible. Police arrive and arrest Skelly, ignoring his injuries.

Later, Suzanne learns Gil has died, and the world she knew collapses.

In the present, Rob tracks Suzanne to a rodeo in Texas, where he sees her on a Kiss Cam kissing Simon and Phoebe. He confronts her later at a bar, forcing her wedding ring onto her hand and insulting her choices.

She throws the ring away and threatens legal action. When Rob grabs her, Simon intervenes, and Rob injures himself in the scuffle.

Simon leads Suzanne out and comforts her as the panic drains from her body.

Another flashback shows Suzanne recovering after the Nebraska riot. Gracie rushes her to call Nora overseas, where Nora cheerfully describes her honeymoon, oblivious to the catastrophe Suzanne has survived.

Suzanne hides the truth and clings to Gracie, caught between the safety she wishes she had and the brutal world she has been thrown into.

The novel closes its major arcs by circling Suzanne’s fractured past and turbulent present, revealing how Gil’s death, Rob’s pursuit, Phoebe and Simon’s companionship, and her own photographs form the map she must follow to reclaim her life.

Characters

Suzanne Delgado

Suzanne is the emotional center of Hot Wax, a woman shaped by absence, chaos, and the abrasive friction between the life she inherited and the life she tried—and failed—to build on her own terms. Her childhood, steeped in the volatile glamour of a touring rock band and the suffocating instability of her mother’s home, creates in her an early self-reliance that later curdles into chronic detachment.

She grows up navigating the world alone—city buses, empty afternoons in the mall, nights listening to contraband tapes—making her fiercely resourceful but emotionally unmoored. As an adult, she drifts in and out of lives and identities: a photographer, a wife, a nomad in an Airstream, a woman who vanishes rather than confront her own grief.

Her relationship with Gil’s legacy is deeply ambivalent; his music wounds her even decades later, yet she keeps his Polaroids, his car, his myths. Much of her inner conflict revolves around the fear that intimacy inevitably collapses into violence or disappearance, and so she keeps others at arm’s length until the fragile safety she finds with Phoebe and Simon cracks her open.

Suzanne’s journey is less about reinvention than about integration—learning to carry the wreckage of her past without letting it dictate her future.

Gil Delgado

Gil is a magnetic, destructive force who exists simultaneously as Suzanne’s adored father, a chaotic artistic genius, and a man undone by the myth of himself. Onstage he is electric—provocative, fearless, reckless—fueling the Kills’ rise while sowing the seeds of their eventual catastrophe.

Offstage, he is a man chasing redemption he never quite reaches, always promising that someday things will be different. His long absences leave Suzanne to weather Nora’s tempests alone, yet his returns ignite her world with possibility, music, and motion.

Gil’s legendary album and the riot in Nebraska show both his power and his fragility: he weaponizes performance but cannot control the consequences, and his downfall becomes Suzanne’s deepest wound. Even in death, he orchestrates her life—from the booby-trapped switches in Blondie to the royalties still replenishing her bank account—forcing her to confront a legacy she has spent adulthood trying to outrun.

Gil is the ghost she carries, the muse she resents, and the father she still grieves.

Nora Delgado

Nora is the counterpoint to Gil’s volatility: grounded, exhausted, and consumed by the daily grind of survival. She is a mother trapped between wanting stability for Suzanne and the resentments she harbors toward Gil’s absences, which leave her to fend for both of them.

Her stress manifests as strictness and suspicion, culminating in the explosive moment when she accuses Suzanne of stealing and ultimately hits her. Yet Nora is not a villain; she is a woman buckling under emotional and financial strain, longing for a life that never quite arrives.

Her second marriage to Nathan offers her a tentative shot at peace, and her honeymoon calls with Suzanne reveal both her attempts at happiness and her distance from her daughter’s reality. Nora’s love is genuine but inconsistent, overshadowed by her own desperation.

Suzanne’s lingering ache for maternal solidity comes from Nora’s inability to provide it when it mattered most.

Rob

Rob represents the life Suzanne tried to choose—quiet domesticity, predictability, a future that looked nothing like her childhood. But he inhabits that role with a mixture of earnestness, fragility, and escalating possessiveness.

His early concern for Suzanne slides into entitlement as he chases her across states, convinced that her leaving is a mistake he must fix. His inability to understand her internal landscape leads him to weaponize stereotypes and grievances: her body, her trauma, her family history.

By the time he confronts her in Texas, the remnants of their marriage have curdled into something coercive and dangerous. Rob’s arc exposes how love can become ownership, how desperation can tip into violence, and how Suzanne’s fear of being trapped was not paranoia but intuition.

His presence in the narrative acts as a stark contrast to the freedom she seeks.

Simon

Simon is an unexpected refuge for Suzanne—gentle, open-hearted, and more emotionally intelligent than his youthful scrappiness suggests. He embodies a way of living that values improvisation over ambition, community over possession.

His ease with affection and his ability to set aside ego allow Suzanne to inhabit a form of intimacy she has rarely known. Simon never pushes; instead, he offers space, curiosity, and a calm steadiness that steadies her.

Even in moments of jealousy or conflict, he de-escalates rather than dominates, protecting Suzanne without claiming her. His affection is rooted in acceptance—of her past, her desire, her trauma—making him a quiet catalyst for her emotional thaw.

Simon becomes not only a potential lover but also a model for the kind of gentleness she long believed was unavailable to her.

Phoebe

Phoebe is the wild, sharp-edged counterpart to Simon’s softness—restless, perceptive, unapologetically embodied. She sees Suzanne clearly almost immediately, her curiosity tinged with both affection and appraisal.

Phoebe’s world is built on reinvention: selling clothes off her own back, transforming junk into art, navigating relationships without jealousy or insecurity. She embodies a fluid, unrestrained womanhood that fascinates and intimidates Suzanne, challenging her sense of what love, desire, and selfhood can look like.

When Suzanne breaks down after hearing her father’s record, Phoebe’s reaction is neither judgment nor pity but fierce empathy. Her open approach to intimacy—sexual and emotional—invites Suzanne into a chosen family that operates outside the constraints that have always suffocated her.

Phoebe is catalyst, caretaker, provocateur, and guide.

Doug

Doug is one of the few stable, nurturing presences across Suzanne’s life. As the record-store clerk who becomes her mentor, then later her editor, he consistently offers her a form of loyalty unconnected to blood, romance, or obligation.

He gives her work, protects her from shoplifters and later from the casual misogyny of the magazine world, and recognizes her talent long before she does. Doug’s support is steady but not smothering; he never demands Suzanne’s secrets and never uses her vulnerability against her.

His encouragement of her photography marks a pivotal moment in her self-definition, and though she ultimately outgrows the world they shared, he remains a figure of genuine care. Doug represents an alternative family—one built on kindness rather than chaos.

Skelly (Eric Skillman)

Skelly is the embodiment of the raw, dangerous glamour of Gil’s world. As the guitarist of the Kills, he exudes charisma mixed with volatility, a man simultaneously protective and destructive.

His bond with Suzanne during the tour is strangely tender: the dart-pendant he gives her symbolizes both mentorship and superstition, a reminder to stay focused even amid chaos. Yet the Nebraska riot reveals the darker side of his intensity.

His violent defense of Gil and Suzanne—followed by his brutal arrest despite his injuries—casts him as a tragic figure destroyed by a system that both fetishized and punished his transgressiveness. For Suzanne, Skelly becomes another ghost of that traumatic night, a symbol of loyalty twisted by violence and injustice.

His presence in her memories is both comforting and haunting.

Gracie

Gracie is the quiet backbone of the Kills’ touring machine—competent, tough, and unflinchingly maternal toward Suzanne. She handles logistics, chaos, and band egos with practiced finesse, yet her most defining role is the silent protector who steps in when Gil’s volatility spills over.

Her care for Suzanne during the Nebraska disaster—holding her, insisting they call Nora, whispering reassurances—cements her as the maternal presence Suzanne always needed but rarely had. Gracie bridges the gap between the band’s anarchic world and the more grounded care that Suzanne is starved for.

Her presence illuminates the patchwork nature of Suzanne’s upbringing: family found in crew vans and backstage corridors rather than at home.

Themes

Identity, Performance, and Self-Reinvention

Suzanne’s life in Hot Wax is shaped by a long pattern of performing different versions of herself to meet the shifting expectations of the people around her. From childhood, she learns that survival often requires presenting a palatable image: the quiet girl who doesn’t ask for too much, the tough kid who wanders mall corridors alone, the dutiful daughter who adapts to the chaos of Gil’s touring life, the efficient assistant who helps Doug spot shoplifters, and later the competent photographer who suppresses her connection to the Kills’ legacy.

Her adult relationships continue this cycle of adaptation. With Rob, she becomes someone measured, muted, adult in the most conventional way, sanding down her rough edges to create stability.

With Phoebe and Simon, that façade loosens and another self emerges—one freer, unguarded, willing to be messy and sensual and unashamed. The book tracks the friction between these identities and the cost of continually reshaping oneself to be acceptable.

Suzanne’s attempts to redefine who she is echo her father’s endless reinventions onstage, where Gil’s persona becomes both his armor and his undoing. For Suzanne, the path toward a more authentic self requires confronting the versions of her identity she created in response to trauma, craving, loss, and expectation.

Her eventual willingness to stop running—from her childhood, from Gil’s legacy, from the relationships that both wounded and shaped her—marks a shift from performing identity to owning it.

Inheritance of Trauma and the Legacy of a Chaotic Childhood

The novel’s emotional core rests on how Suzanne carries the psychological debris of her upbringing. The violence, instability, and volatility surrounding Gil and Nora leave marks that follow her into every adult relationship.

The chaos of backstage rooms, explosive arguments between her parents, and a near-fatal night in Nebraska do not disappear with distance or time. Instead, they crystallize into habits of withdrawal, mistrust, emotional dissociation, and a need to disappear before she can be abandoned.

Even her career in photography reflects this inheritance—she frames moments without inserting herself, observing life instead of stepping fully into it. Hearing Gil’s voice on old recordings hits her with visceral force because it reminds her that loss does not erase what a person has endured; it only buries it until something cracks the surface.

Suzanne’s adult choices—her retreat from Rob, her attraction to the nomadic world of Phoebe and Simon, her instinctive flight from confrontation—stem from the childhood lesson that safety is temporary and love can implode without warning. The novel shows that trauma is not a single event but an ongoing influence shaping how someone interprets desire, affection, partnership, and conflict.

Suzanne’s journey is not toward erasing her past but toward acknowledging how deeply it has shaped her and learning to let that history inform rather than imprison her.

The Destructive Seduction of Art, Fame, and Subculture

Gil’s world—the music, the touring, the costumes, the swaggering mythology of the Kills—shimmers with the hypnotic allure of artistic rebellion. But behind that glamour sits a harsh truth: the kind of art that courts danger often consumes its creators and everyone orbiting them.

Suzanne grows up surrounded by the contradictions of this environment. She sees the thrill of performance and the electricity of creation, but also the dysfunction, exhaustion, substance abuse, and ego clashes hidden behind the curtain.

Fame functions less as a reward and more as a furnace that burns through relationships and stability. Gil wants success so desperately that he overlooks the damage inflicted on the people who love him.

His band’s notoriety fuels a fan culture eager for outrage, culminating in a riot that permanently scars Suzanne’s life. The novel depicts how subcultures built on provocation can attract both devotion and violence, and how artistic communities can blur boundaries between authenticity and spectacle.

Even decades later, Suzanne encounters the remnants of this world—vinyl in flea markets, gossip among music writers, strangers mythologizing the man she knew as a flawed father. The seductive pull of that world remains, yet she also recognizes the devastation it left behind.

Her relationship with her own art is shaped by this tension between creation as freedom and creation as self-destruction.

Freedom, Mobility, and the Temptation of Escape

Movement defines Suzanne’s life—childhood bus routes across Baltimore, reckless miles in Blondie, cross-country tours, cramped travel in the Lifeboat, and impulsive disappearances when emotions become overwhelming. The road is both refuge and threat: it offers release from suffocating relationships, but it also prevents her from forming a stable sense of home or self.

She internalizes the belief that motion is safety, that pausing invites danger. Gil lived this philosophy, treating the road as a stage for reinvention, and Suzanne inherits this rhythm without ever choosing it.

As an adult, she repeats the pattern—leaving Rob abruptly, drifting into Phoebe and Simon’s itinerant life, convincing herself that constant movement equals freedom. But the novel gradually shifts this idea, showing that escape is not the same as autonomy.

Real freedom comes when she stops using travel as avoidance and begins to choose connections that do not trap her. Her time with Phoebe and Simon marks a turning point: they also live on the road, yet their mobility carries intention rather than panic.

They move because they want to, not because they are running. As Suzanne slowly confronts her past, she begins to imagine freedom not as flight but as the ability to remain without fear.

Intimacy, Control, and the Complexities of Love

Across the story, relationships—romantic, familial, platonic—are shaped by power dynamics, desire, and the competing needs of emotional safety and independence. Suzanne’s relationship with Rob highlights her fear of enclosure; he craves certainty, domesticity, and traditional milestones, while she feels smothered by the very things he believes signify love.

His attempts to “fix” her reveal how affection can veer into control when one partner insists on defining the other’s needs. In contrast, her relationship with Phoebe and Simon offers a radically different model of intimacy, one built on negotiation, non-possession, and fluid boundaries.

Their openness challenges Suzanne’s assumptions about jealousy, desire, and belonging; they see her not as someone to be shaped or saved but as someone to be understood. This contrast exposes what she has always lacked: relationships where her bruised history does not need to be hidden or justified.

The novel argues that intimacy requires the courage to be known—not the curated version of oneself, but the person behind all the defenses. Suzanne’s gradual willingness to let others witness her grief, her anger, and her longing marks her first real step toward love that does not demand the loss of self.

Memory, Photography, and the Fight to Claim One’s Story

Photography functions as Suzanne’s method of making sense of the world when everything else feels uncontrollable. As a child, the Polaroid camera gives her a way to freeze the chaos around her, to capture fleeting moments of tenderness, danger, or defiance.

The photographs she keeps become a private archive—proof of experiences she cannot fully articulate, especially to adults who overlook her or misunderstand her. In adulthood, her career in photography intersects uneasily with her family history.

The darkroom becomes a haven where she can impose order and create meaning separate from the legacy of Gil’s music. Yet even this refuge is infiltrated when coworkers play the Kills’ album, reminding her that no medium can fully distance her from the past.

Throughout the book, the physical act of taking, keeping, and revisiting images serves as a confrontation with memory. The photos she carries are not sentimental keepsakes but anchors—evidence of who she was, who her parents were, and the emotional truth of moments that others tried to rewrite or ignore.

By reclaiming these memories, she begins to claim her own narrative, resisting both the mythologizing of Gil’s fans and Rob’s patronizing assumptions about her damagedness. In doing so, she steps into authorship of her own life rather than remaining a character in other people’s stories.