How To Kill a Witch Summary And Analysis

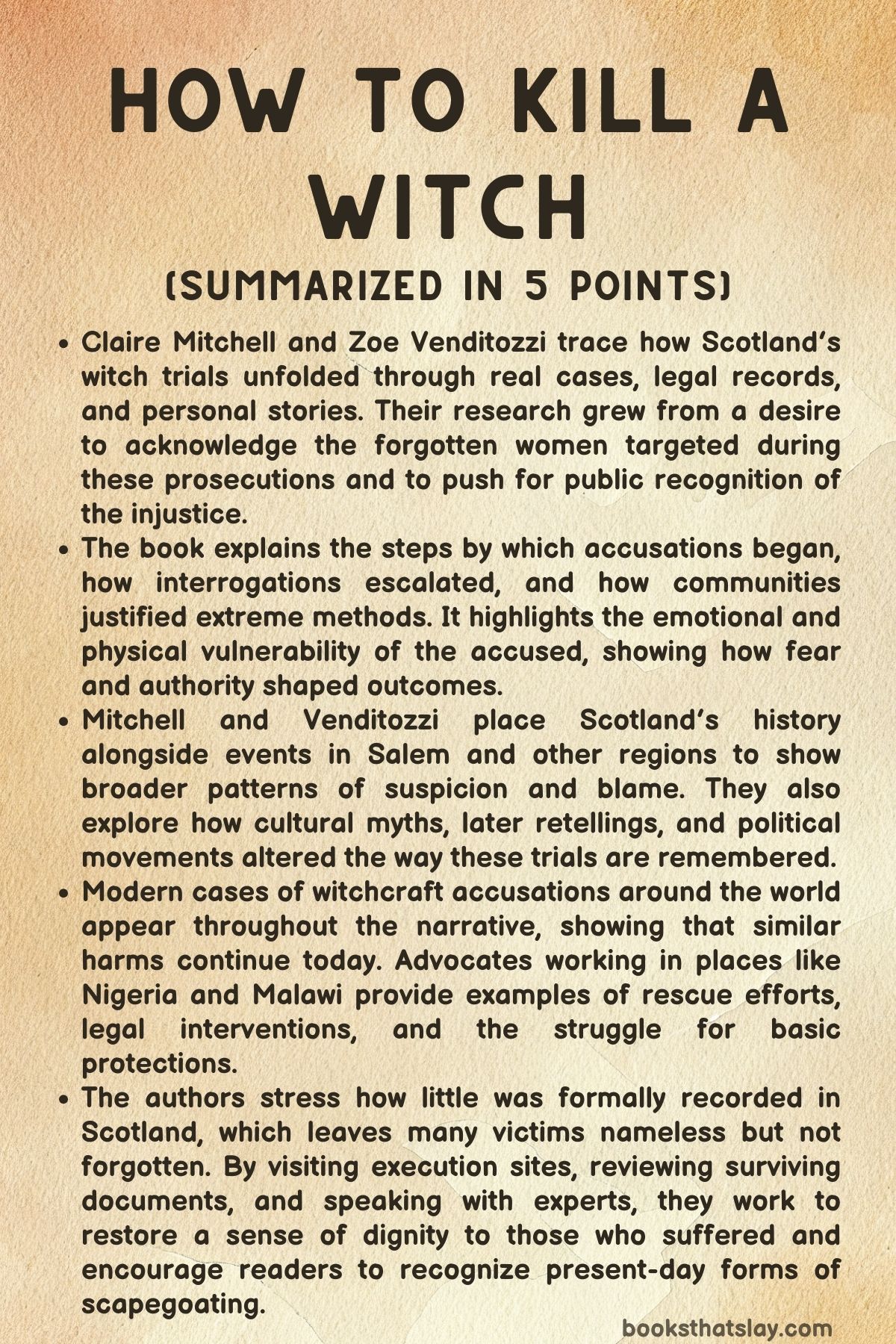

How to Kill a Witch by Claire Mitchell and Zoe Venditozzi is a historical and cultural examination of witch trials in Scotland and beyond, told through research, travel, and activism. The authors explore the forces that built these prosecutions, the people who suffered under them, and the long effort required to restore their names.

They move between past and present to explain how fear and power shaped accusations, how records vanished or were never kept, and how modern societies still echo the same patterns. The book also follows the creation of the Witches of Scotland campaign, which works for apology, pardon, and memorial.

Summary

HOW TO KILL A WITCH begins with Claire Mitchell’s research into a contemporary case of grave violation, which unexpectedly led her toward Scotland’s history of witch trials. As she examined the role of Sir George “Bloody” Mackenzie, a seventeenth-century legal figure who oversaw brutal prosecutions, she was struck by the human cost hidden behind legal records.

One woman’s question—whether she could be a witch without knowing it—revealed how fear could distort someone’s understanding of their own identity. This emotional response pulled Claire deeper into studying Scotland’s neglected past.

A second realisation arrived when Claire noticed the absence of women in Edinburgh’s public memorials. After reading a book about the lack of women represented in Scottish history, she realised that even in places where countless women had been executed for witchcraft, they remained unacknowledged.

With over two thousand known accusations and hundreds of confirmed executions, the silence around these events seemed deliberate. This personal moment led her to commit to seeking an apology, a pardon, and a national memorial for those who had suffered.

From this resolve came the Witches of Scotland campaign.

Around this time, Claire reconnected with novelist Zoe Venditozzi, who was also fascinated by true crime. Zoe had wanted to start a podcast but lacked a focus.

Claire suggested a podcast about Scotland’s forgotten witches. What began as a simple recording on an iPhone quickly gathered an audience, drawing international attention.

Their combined efforts contributed to Scotland issuing its first formal apology, delivered on International Women’s Day in 2022, acknowledging centuries of injustice. The campaign then expanded toward legislative pardons and the hope of a permanent memorial.

The book explains how accusations unfolded step by step. The authors travelled across Scotland, tracing execution sites, graveyards, and archives.

They expected cruelty, but the sheer methodical nature of the process still shocked them. What began as a satirical “manual” for killing a witch became a detailed study of how authorities identified suspects, tortured them, extracted confessions, conducted trials, and erased the victims afterward.

Their work shows not only the historical reality but also the global echoes in modern society, where violence against women and accusation-based harm still take shape in different forms.

The authors describe Scotland’s sparse documentation. Records were often limited to financial notes—payments to executioners or witch-prickers—while confessions, verdicts, and personal details were frequently lost.

Most of what remains comes from scattered contemporary writings, oral tradition, and the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft, which compiles what can be recovered. A major section examines the North Berwick trials, known primarily through the pamphlet Newes from Scotland.

They recount how a maidservant, Geillis Duncan, became the start of a massive hunt after her employer accused her. Under torture she named others, leading to confessions extracted through physical torment, sleep deprivation, and invasive searches for supposed Devil’s marks.

Among the accused were respected community members such as Agnes Sampson and Dr. Fian.

Their stories show the extreme measures used against the accused: body shaving to find marks, the use of bootikins, pin insertion under nails, and forced confessions linking ordinary people to elaborate conspiracies. The pamphlet presented these confessions as proof that witches attacked the king himself, feeding a political narrative that suited royal fears and religious anxieties.

Beyond North Berwick, the book includes stories from Orkney, Aberdeen, and other regions. These accounts show how torture shaped confessions and how families were destroyed alongside individuals.

Allison Balfour’s case demonstrates the cruelty inflicted upon relatives to force admissions. Janet Wishart’s case shows how neighbourhood tensions, folk beliefs, and coincidence could escalate into charges of decades-long sorcery.

The book compares Scotland’s forgotten victims with Salem, where families preserved records and later fought for justice. Salem eventually cleared names and created memorials, while Scotland left its victims largely unremembered until modern activism revived the issue.

The authors also examine how Salem evolved into a site of tourism and a symbol used in modern language and politics. They discuss how the idea of a witch has shifted, from an accused criminal to a cultural identity adopted by many today.

The legal structure of Scottish trials is explained through historical writings and examples. Many trials were handled not by the highest courts but by small local commissions, often influenced by local pressures and poor evidence standards.

The story of Isobel Gowdie illustrates the complexity of confessions, which often mixed folklore, fear, and the interrogator’s expectations. Her extensive confessions describe contact with the Devil, magic, and flights through the air, yet the authors emphasise the conditions under which these statements were made—conditions intended to break a person both physically and mentally.

Statistics suggest that most accused were executed, usually by strangling followed by burning. The Paisley trials of 1697 show how children and adults could accuse dozens, how ministers shaped juries through warnings, and how towns later struggled with the legacy of these deaths.

The authors recount the final legal execution for witchcraft in Britain: Janet Horne in Dornoch, an elderly woman likely suffering from illness, who was condemned after a brief and possibly unlawful proceeding.

The book also describes the mechanics of burning, using historical cases and modern forensic explanation. Rather than instant destruction, these executions were prolonged and horrifying.

Clothing ignited first, the body contracted from heat, and full consumption took hours. Scattered bone remained unless crushed.

These details emphasise the physical reality hidden behind legal records.

From there, the narrative moves forward to the twentieth century with the case of medium Helen Duncan, prosecuted under the old Witchcraft Act in 1944. Wartime secrecy, Spiritualist enthusiasm, and government suspicion all shaped her trial.

She became the last person convicted under that law, which was replaced in 1951.

The story then turns global. The authors highlight present-day violence connected to witchcraft accusations, especially against women, children, and people with albinism in countries where fear, poverty, and traditional beliefs combine.

Activists such as Leo Igwe work to rescue victims, push for prosecutions, and promote critical thinking. The 2021 UN resolution condemned practices that continue to cause harm worldwide, showing that the patterns described in historical cases are far from gone.

Finally, the book addresses modern remembrance. Scotland has limited memorials, and many victims lie in unmarked or lost graves.

The authors argue that recognition matters: acknowledging past persecution helps prevent future injustice. Through campaigns, public art, research projects, and building communities committed to fairness, they hope to restore the humanity of those who suffered and encourage societies to confront how fear can still shape judgement.

Key People

Claire Mitchell

Claire Mitchell emerges in HOW TO KILL A WITCH as a modern legal mind driven by a profound sense of historical injustice. Her journey begins academically, with research into historical crime, but transforms into a personal and political mission when she confronts the forgotten cruelty of Scotland’s witch trials.

Her character blends intellectual rigor with emotional responsiveness; the moment she reads about a woman asking whether one could be a witch without knowing it becomes a turning point that moves her from scholarship to activism. Claire is also shaped by her acute awareness of women’s erasure from public history.

The stark absence of female statues in central Edinburgh, contrasted with the brutal history beneath its cobblestones, fuels her conviction that silence itself is a continuation of harm. Determined, methodical, and deeply compassionate, she spearheads the Witches of Scotland campaign and becomes a catalyst for Scotland’s formal apology.

Her ability to connect legal expertise with storytelling and public engagement makes her both a champion of historical truth and a figure who bridges past and present injustices.

Zoe Venditozzi

Zoe Venditozzi complements Claire as a partner whose creativity and curiosity help transform historical advocacy into a global conversation. A novelist and teacher with an existing fascination for true crime, Zoe brings a narrative sensitivity that helps make the subject accessible and emotionally resonant.

Her willingness to experiment—seen in their first improvised podcast recording—reveals a character unafraid of imperfection if the mission is meaningful. Zoe serves as both collaborator and translator, shaping raw historical data into compelling narrative forms that resonate with listeners and readers.

Her empathy is apparent in the way she approaches the stories of persecuted women, always emphasizing their humanity over sensationalized myth. Through her, the book gains warmth, humor, and reflective grounding, showing how modern women can reclaim stories long dismissed or distorted.

Zoe’s role illustrates how activism often requires not only legal or historical authority but also storytelling that can awaken public conscience.

Sir George “Bloody” Mackenzie

Sir George Mackenzie represents the darker institutional forces that powered Scotland’s witch persecutions. As a powerful seventeenth-century lawyer and royal official, he embodies the intersection of religious fear, state authority, and patriarchal control.

His involvement in prosecuting dissenters and accused witches illustrates the legal machinery that turned superstition into state-sanctioned brutality. Mackenzie’s legacy is deeply paradoxical: though respected in his time for legal scholarship, he is remembered in this narrative as a symbol of ruthless zeal, earning the epithet “Bloody.

” His character highlights how individuals within power structures can perpetrate atrocities while believing themselves righteous, illustrating the moral blindness that emerges when law becomes an instrument of ideology rather than justice. Mackenzie’s actions echo through the book’s modern themes, demonstrating how the state’s authority, once misdirected, can leave centuries-long scars.

Geillis Duncan

Geillis Duncan stands as a tragic figure whose exceptional abilities—particularly her healing skills—make her a target in a climate of fear. Her character illuminates how suspicion often fell upon young, working-class women with talents or independence that unsettled their employers.

Geillis becomes the spark that ignites the North Berwick panic, not through malice but through coerced confession under torture. Her story exposes the dynamics of power and vulnerability: as a maidservant, she is isolated, easily dominated, and unable to resist the machinery of accusation that her employer unleashes.

Through her, the narrative shows how witch trials did not simply punish supposed deviance but exploited those at the lowest rungs of social hierarchy. Geillis represents both victimhood and the tragic chain reaction of forced denunciations that ensnared dozens of others.

Agnes Sampson

Agnes Sampson is portrayed as an elder healer whose wisdom and age, rather than earning respect, become grounds for suspicion in a society primed to fear female knowledge. Her interrogation, shaving, and bodily examination reveal the systematic degradation inflicted upon accused women.

Her coerced confession—complete with fantastical elements—demonstrates the terrifying efficiency of torture in manufacturing “truth. ” Agnes’s ability to repeat private words spoken by King James, likely learned through ordinary gossip or interrogation coaching, nonetheless convinces the monarch of her “powers,” revealing how even rulers could be manipulated by fear and superstition.

Her character illustrates the cruel paradox of the trials: the more dignified, composed, or intelligent the woman, the more convincing her “guilt” appeared to authorities.

Agnes Thomson

Agnes Thomson’s narrative underscores the surreal and often grotesque creativity of witchcraft accusations. Her alleged use of poison from a hanged toad and participation in rituals meant to conjure storms reflect a world in which natural misfortune was readily attributed to malice.

Her character embodies the way accused women were forced into confessions that mirrored preexisting demonological fantasies rather than any lived reality. She becomes a conduit for societal fears about the safety of the king, maritime disaster, and foreign influence.

Agnes’s story emphasizes how accusations served political ends, transforming ordinary women into symbols of treason and cosmic threat.

Dr. Fian

Dr. Fian’s character offers a rare view of a male accused in a system overwhelmingly targeting women.

As a schoolmaster, he occupies a respected social position, yet even this does not protect him once he is implicated. His story is marked by extremes: the brutality of his torture, his initial confession, his attempted recantation, and his dramatic escape.

Fian’s refusal to reconfess despite excruciating torture reveals a core of resilience and humanity that contradicts the monstrous figure authorities tried to mold him into. His character underscores how the trials consumed not only marginalized individuals but anyone caught in the net of accusation, and how male victims were often folded into narratives of devilish conspiracy that mirrored gendered fears but expanded beyond them.

Allison (Margaret) Balfour

Allison Balfour represents one of the most heartbreaking examples of cruelty justified by legal process. Her character is defined by dignity under extreme duress: even when tortured for two days, she does not confess until her family is tortured before her eyes.

Her story exposes the moral bankruptcy of a system willing to destroy an entire household to force a single confession. Allison’s retraction at the gallows is a powerful assertion of truth in the face of death, marking her as a symbol of integrity amid state-sanctioned barbarity.

Her suffering reveals how witch trials served as instruments of coercion rather than justice, with whole families destroyed for political convenience.

Janet Wishart

Janet Wishart appears as a long-standing community scapegoat, burdened with decades of accumulated rumors and fears. Her portrayal demonstrates how witch accusations often developed over years, drawing from personal grievances, local tragedies, and superstition that attached itself to particular individuals.

Janet’s conviction on eighteen counts shows how trials became repositories for unresolved communal anxieties. Her banished family members, despite acquittal, highlight the lasting stigma associated with such charges.

She becomes a symbol of intergenerational devastation and the way communities reinforced their own myths through repeated suspicion.

Tituba

Tituba’s story, though situated in Salem rather than Scotland, reveals the intersection of race, enslavement, and vulnerability in witchcraft accusations. As an enslaved woman of color, she occupies the lowest social position, making her an easy target for projection and blame.

Her confession—likely coerced—becomes a narrative seed that shapes the trajectory of the entire Salem crisis. Tituba’s survival, achieved only through confession, demonstrates the impossible choices facing the powerless.

Her later erasure from records, followed by her distortion in literature and popular culture, shows how marginalized women are doubly wronged: first by persecution, then by misremembering.

Isobel Gowdie

Isobel Gowdie is one of the most compelling figures in Scottish witch-trial history, known for her elaborate and vivid confessions. Her character encapsulates the psychological torment inflicted on the accused.

Whether her stories arose from coercion, exhaustion, imaginative expression, or a desperate attempt to align with interrogators’ expectations, they reveal a woman caught in an unforgiving system where silence was impossible and truth irrelevant. Her descriptions of coven meetings, encounters with the Devil, and journeys to the fairy court reflect not reality but a cultural script fed to her by men determined to validate their worldview.

Isobel becomes both storyteller and victim, her voice preserved only because it served the goals of those who condemned her.

Christian Shaw

Christian Shaw, the central figure in the Paisley trials, illustrates how social status, childhood testimony, and performative illness could combine into lethal accusation. As a young girl whose strange fits and regurgitations baffled physicians, she becomes the unwitting instrument of destruction.

Her character raises complex questions: whether she acted deliberately, subconsciously, or under influence, her accusations led directly to executions. Her later prosperous life contrasts sharply with the fate of those she condemned, creating a haunting dissonance in the narrative.

Christian embodies how children, too, were shaped by the fears and expectations of their society, capable of triggering tragedies far beyond their understanding.

Janet Horne

Janet Horne, the last woman executed under Britain’s witchcraft laws, appears as a tragic emblem of vulnerability in old age. Likely suffering from dementia and caring for a disabled daughter, she becomes an easy target for community suspicion.

Her trial is hastily and illegally conducted, reflecting a society eager to rid itself of perceived burdens. Janet’s gentle, confused behavior—warming her hands at the fire meant to kill her—renders her death especially poignant.

Her character highlights how accusations often targeted those who could defend themselves least, transforming frailty into supposed malevolence.

Helen Duncan

Helen Duncan stands at the intersection of performance, belief, and legal persecution in the twentieth century. A dramatic personality with a deep desire to connect grieving families with lost loved ones, she becomes a celebrated medium at a time when Spiritualism offered solace to the war-stricken.

Whether through trickery, intuition, or a blend of both, her séances tap into a powerful cultural need. Helen’s prosecution under the archaic Witchcraft Act reveals as much about wartime paranoia as it does about her own actions.

Her supporters’ insistence on validating her powers ironically contributes to her conviction, making her a victim of both state suspicion and her own community’s fervor. Helen embodies the blurred lines between faith, fraud, and fear, serving as the last modern echo of a centuries-old legal tradition.

Leo Igwe

Leo Igwe represents the contemporary fight against the harms of witchcraft accusations. As an activist confronting violence in Nigeria and Malawi, he brings intellectual clarity, moral courage, and relentless persistence to a deeply dangerous cause.

His character is marked by a practical compassion—rescuing victims, paying hospital bills, relocating families—as well as a systemic understanding of the social structures that perpetuate belief-based violence. Leo embodies the book’s argument that witch hunts are not historical relics but ongoing human rights crises.

Through him, the narrative shifts from remembering the past to confronting the present.

Analysis of Themes

Gender, Power, and the Targeting of Vulnerable Women

Across HOW TO KILL A WITCH, gender operates as a quiet but constant force shaping who is seen, who is feared, and who is punished. The women accused in Scottish witch trials were often those with the least protection—widows, the elderly, the poor, women whose behavior stepped outside narrow expectations, or simply those who could not defend themselves against rumor or hostility.

The narrative shows how authority figures used the law not only to prosecute supposed supernatural crimes but to reassert control over women whose existence, labor, or independence unsettled the social order. Even cases involving respected or higher-status women illustrate how precarious female safety was; status only slowed the fall, it did not prevent it.

The book situates this imbalance within a broader global pattern, connecting seventeenth-century accusations to ongoing persecution of women and girls in parts of Africa and Asia, where accusations still erase lives under the guise of moral or spiritual threat. By tracing modern activism—such as the work of Leo Igwe and the United Nations’ acknowledgment of witchcraft-linked violence—the authors underscore that misogyny adapts rather than disappears.

Women are still blamed in moments of instability, still framed as sources of harm when communities seek easy answers. The campaign for pardons and memorials in Scotland reflects an attempt to counteract this long history, not simply by documenting it but by challenging the mechanisms that allowed such violence to persist.

In doing so, the book argues that remembrance is not symbolic but a corrective to centuries in which women were silenced, forgotten, or treated as expendable. Gender becomes a lens through which both past injustices and contemporary dangers can be understood, revealing how deeply patriarchal structures shape ideas about guilt, danger, and credibility.

The Machinery of Fear and the Construction of Scapegoats

Fear in HOW TO KILL A WITCH functions less as an emotion and more as a system: predictable, triggered by crises, and directed at convenient targets. Whether the spark was political unrest, failed harvests, illness, or unexplained behavior, fear produced a hunger for explanation that authorities and communities channeled toward individuals already on the margins.

The authors demonstrate that Scottish witch trials were not chaotic eruptions but carefully structured operations. Commissions, interrogations, bodily examinations, and confessions created a bureaucratic framework that made the process feel orderly and justified, even as it destroyed lives.

This pattern appears again in Salem, where local tensions and factional rivalries fed accusations that spiraled into legal calamity. The book uses these historical events to show how fear hardens into policy when leaders treat panic as proof.

King James VI’s personal anxieties about supernatural threats influenced prosecutions, while later cultural retellings transformed Salem into a cautionary emblem of mass hysteria. The same formula—fear, a triggering event, and a chosen scapegoat—echoes in modern examples, whether political rhetoric about “witch hunts,” moral panics amplified by media, or communities responding to poverty and uncertainty by labeling vulnerable individuals as dangerous.

By examining periods of crisis from the sixteenth century to the present, the authors reveal that societies often resolve fear by outsourcing guilt, creating narratives that identify an enemy rather than confront the underlying issues. The theme exposes how institutions, leaders, and cultural beliefs collaborate to turn anxiety into persecution.

It also warns that unless fear is recognized as a political tool, its consequences will continue to fall on those least able to resist.

Violence, Torture, and the State’s Claim to Moral Legitimacy

A striking thread in HOW TO KILL A WITCH is the persistent effort to depict state violence as righteous action. Torture, whether physical or psychological, is framed in the historical records as a means of extracting truth rather than enforcing conformity.

The text dismantles this notion by presenting the human consequences of these practices: bodies broken by the bootikins, skin pierced by witch-prickers, women stripped and searched under the guise of finding Devil’s marks, and prisoners kept awake until exhaustion forced false admissions. The authors show that confessions were less revelations than performances shaped by pain and the interrogators’ expectations.

Even legal distinctions that claimed to prohibit torture were circumvented through techniques that avoided the name while inflicting equivalent suffering. Execution itself, particularly burning, is described with clinical specificity, revealing how communities normalized the spectacle.

Expert testimony from forensic specialists clarifies how prolonged and traumatic these deaths were, stripping away the sanitized distance that historical summaries often create. Yet the violence was not only physical.

It extended to destroyed reputations, ruptured families, and the erasure of identities through poor recordkeeping. The state constructed its moral legitimacy by insisting that these acts protected the community from evil, but the book illustrates that such legitimacy relied on silencing those who were harmed.

Modern parallels reinforce the argument: contemporary accusations, beatings, and killings tied to witchcraft accusations follow similar patterns where the punishment is portrayed as necessary, even benevolent. By exposing the machinery that upholds such violence, the authors question how legal systems justify harm and how communities become complicit when cruelty is presented as duty.

Memory, Erasure, and the Fight for Recognition

One of the most powerful themes in HOW TO KILL A WITCH is the struggle against historical silence. Scotland’s sparse records, fragmented documents, and missing graves reveal how thoroughly accused individuals were erased, both by contemporaries who saw them as unworthy of remembrance and by later generations who failed to preserve their stories.

The authors emphasize how this absence shapes public understanding: places where hundreds of women were executed now display statues of men, while those who died have no markers. In contrast, Salem’s long record of petitions, preserved papers, and cultural engagement demonstrates how memory can evolve into recognition.

The difference between the two histories illustrates how much collective will determines who is remembered. When memorials exist, they can reshape cultural narratives; when they are absent, injustice becomes easier to ignore.

The Witches of Scotland campaign emerges as a response to this void, seeking apologies, pardons, and physical memorials not as symbolic gestures but as acts that restore dignity and presence to people denied both. The book connects this with broader international efforts to acknowledge victims of modern witchcraft-linked violence, arguing that remembrance is a prerequisite for justice.

Reconstructing faces, like that of Lilias Adie, or mapping execution sites becomes a way to return individuality to those reduced to accusations. This theme challenges readers to consider how societies decide whose lives matter enough to be recorded and honored.

Memory becomes both a historical project and a political act—one that resists the erasure that once enabled persecution and warns against the ease with which vulnerable communities can once again be pushed into silence.