Make Me a Monster Summary, Characters and Themes

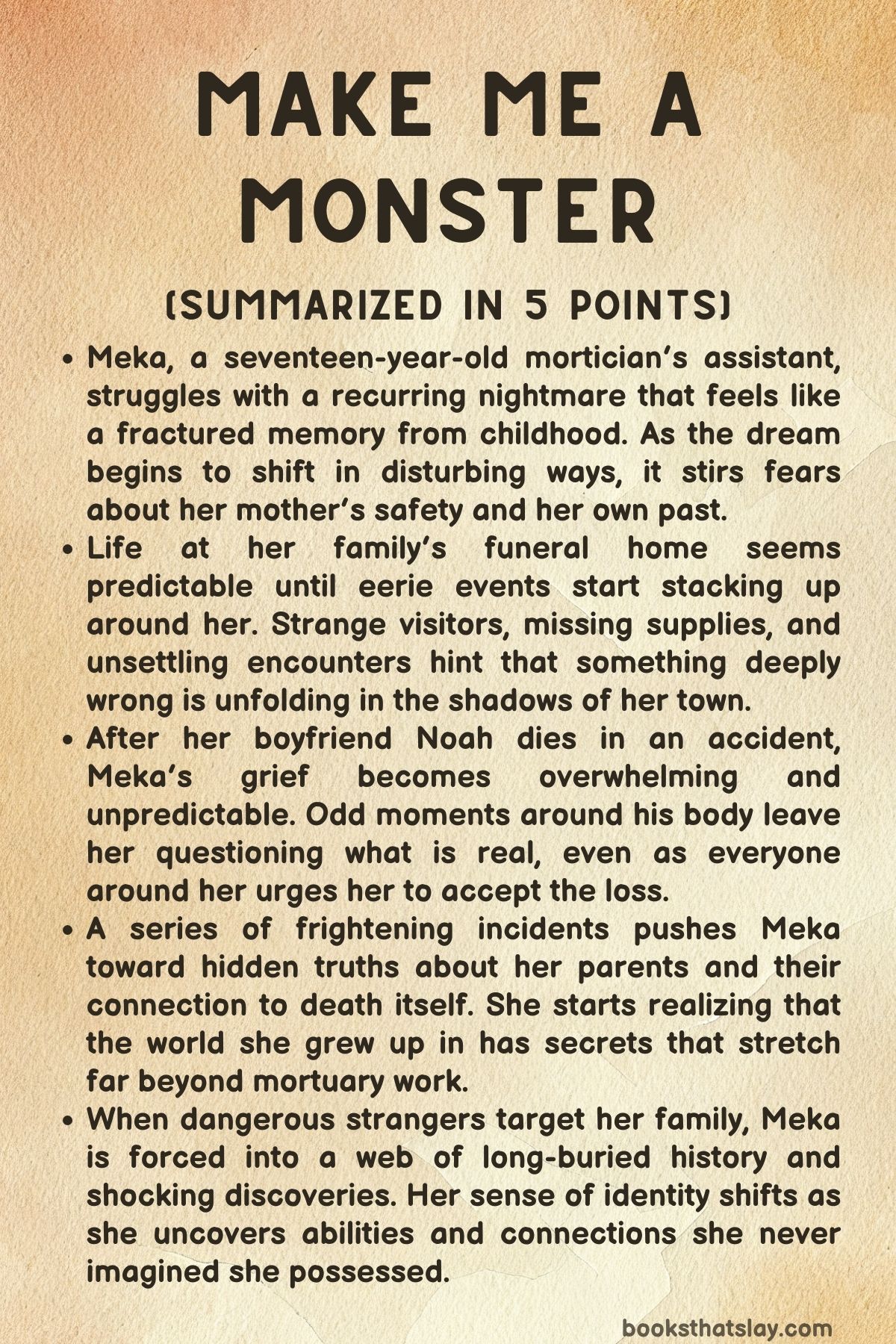

Make Me a Monster by Kalynn Bayron blends coming-of-age fear, mystery, and family secrets into a story about a girl raised among the dead who must confront what it means to bring life back where it no longer belongs. The novel follows seventeen-year-old Meka Redwood, who lives with her parents in the funeral home they run in Ithaca.

She grows up around corpses, rituals, and the quiet dignity of death, but she also battles a recurring nightmare that hints at a past she cannot understand. When strange figures appear in town, her boyfriend dies under suspicious circumstances, and bodies start behaving in ways they shouldn’t, Meka is forced to uncover the truth about her family’s legacy and her own unsettling abilities.

Summary

Meka Redwood lives at Redwood Funeral Home with her parents, Kassie and Jonathan. She has spent her life helping prepare the dead and recently became the town’s youngest certified mortician’s assistant.

But underneath her confidence lies a recurring nightmare: a childhood memory of riding in a car with her parents, her mother looking back with an unreadable expression, and then an explosion of orange light. She always wakes before the ending, but lately the dream has changed.

Now she finds herself outside, staring at the stars, chest burning, screaming. The dream leaves her uneasy and frightened of what she can’t remember.

Life at the funeral home is usually structured and calm. After her certification celebration, she returns to her routine: preparing bodies, arranging viewings, and helping grieving families.

She tries to ignore the deepening nightmares while spending time with her friends Noah, Caleb, and Cipriana. Yet strange moments begin to intrude on normal life.

She hears her name whispered in empty rooms. A corpse’s eyes open during prep.

Ravens behave oddly. A pair of well-dressed strangers arrive demanding to see her father, who drives them away while visibly shaken.

One night, Meka accompanies Jonathan on a late pickup. In the hearse, she accidentally touches a glowing green object wedged under the seat, and the corpse they’re transporting suddenly jerks upright.

Though Jonathan insists it’s just a postmortem reaction, Meka feels something deeper is wrong. The unease only grows when two strange men appear behind her and her friends at the movies.

Later, the same type of men tailgate Caleb’s car before speeding off.

Despite the unsettling events, life continues until the night her world collapses. After a quiet evening with Noah, Meka goes to bed peacefully.

But the next morning, her mother collapses into despair: Noah slipped on the ice while retrieving food, hit his head, and died. Meka is shattered.

Days pass in a blur of grief. When Noah’s body arrives at the funeral home, she begs to see him, and when she finally does, she notices every detail her mother has repaired.

As she leans down to kiss him goodbye, she hears him sigh. Her mother gently insists it was a trick of grief.

At the memorial, the casket is sealed earlier than promised, and Meka’s attempt to reopen it causes a scene. She feels watched at the cemetery and spends weeks sinking into grief.

Her nightmares intensify, showing a bright light, a prep table, and her father holding a bloodstained book. She becomes convinced someone is stealing supplies from the funeral home.

A raven outside mimics human speech, warning her to get out. A hooded figure follows her home, then disappears.

Her father begins acting strangely, preparing for a trip with items that smell of smoke. Soon after, a disturbed man attacks Meka and Kassie inside a clothing shop.

They survive only because someone unseen intervenes. Things unravel further when a delivery arrives and three well-dressed men appear again.

They pressure Jonathan about a previous incident. He leaves with them, afraid, and tells Meka to protect her mother.

Alone with Kassie, Meka finds an envelope on the back step containing the bracelet Noah made for her—the same bracelet she placed on his wrist inside his casket. As they argue about it, Kassie slices her own hand.

The cut reveals mortuary wax instead of flesh. Before Meka can react, her phone rings.

Caller ID: Noah. His voice warns her to get out of the house.

Running upstairs, Meka finds her mother confronting a blond man with a hunting knife—the same man who watched them at the movie theater. He attacks Kassie, slicing open her shoulder.

There is no blood. A hooded figure bursts in, fights him, and drives him out.

When the hood falls, Meka sees Noah, alive but injured and stitched together.

Meka passes out and wakes in the prep room with Kassie and Noah barricaded inside. Here, Kassie finally tells the truth.

Years ago, the nightmare Meka remembers wasn’t just a dream. Kassie truly died in a car crash.

Jonathan resurrected her using a family book passed down for generations. Kassie has been dead ever since, relying on wax, makeup, formaldehyde, and a product called Smithfield’s to keep her body functional.

The same book was used to bring Noah back after his supposed accident.

Kassie teaches Meka how to repair her decaying shoulder and Noah’s damaged limbs. The attackers who have been stalking them, including the blond man, are other reanimates looking for the book.

When Jonathan is kidnapped, Meka, Kassie, and Noah search for clues. They visit Maxine Cliff, Noah’s mother, who refuses to accept his condition.

After she is safely hidden, a threatening call arrives from Jonathan’s phone. A stranger demands the book in exchange for Jonathan’s life.

Meka realizes the book must still be with her grandfather, buried in the local mausoleum. At the vault, they retrieve the coffin and uncover a glowing, intangible book only Meka can fully see.

When she touches it, the mausoleum shakes and coffins rattle. They are ambushed by the same reanimates.

During the fight, one man steals the book, while another seizes Noah and hacks off his hand before escaping.

A reanimated raven soon brings a note in Jonathan’s handwriting referencing Frankenstein, pointing them toward Dundas Castle in Roscoe, where scenes from the 1931 film were shot. Believing Jonathan is held there, they make the dangerous trip.

Inside the crumbling castle, they discover a group of reanimates preparing to use a young woman’s corpse for parts. Jonathan is forced to reanimate her while Meka is held hostage.

When he refuses, they threaten Meka, and he completes the ritual under duress.

Noah intervenes, chaos breaks out, and a towering hooded figure appears. All the reanimates kneel.

The figure reveals himself as Frankenstein’s original monster, created centuries ago by Johann Konrad Dippel. Still decaying and replacing body parts, he has manipulated generations of reanimators.

He claims Meka is Dippel’s last descendant, able to reanimate without the book, and demands she join him.

He attacks, ripping off Kassie’s arm and nearly killing Jonathan. Forced to prove her power, Meka reanimates the dead woman with only her touch.

Horrified, she refuses to do more. A violent battle erupts.

She and Noah fight back. She drives a knife into the monster’s neck, and they fall through a window.

Though beheaded, the monster continues to move until they dismember him fully.

Inside the castle, the remaining reanimates lie dying. Kassie, with her body nearly destroyed, tells Meka she’s tired of existing in a form that’s falling apart.

Noah, whose body is deteriorating, asks to be released as well. Jonathan reveals that the book’s destruction will end all reanimates.

Devastated, Meka agrees. Jonathan burns the book.

Kassie, Noah, and all the others become still at once.

They cremate the monster, burn the castle, and return home. Weeks later, Meka scatters her mother’s ashes at a waterfall.

Noah is reburied with his hand returned to him. Yet the monster’s final message lingers.

Curious and fearful, Meka touches the corpse of a woman at the funeral home and brings her back to awareness with no ritual or book.

The truth becomes clear. Meka herself carries the spark.

And now she must decide how to live with the power that could change death forever.

Characters

Meka Redwood

Meka stands at the center of Make Me a Monster, shaped by grief, secrecy, and an inheritance she never asked for. Her life inside the Redwood Funeral Home forces her to grow up around death, granting her both unusual composure and an almost spiritual intuition about the space between life and lifelessness.

She is compassionate, meticulous, and deeply loyal, which becomes both her strength and her torment as the truth of her family lineage unfolds. Meka’s recurring nightmares foreshadow the buried truth of her mother’s death and her own latent abilities.

Her emotional honesty—particularly her vulnerability in grief after Noah’s death—creates a powerful contrast to the cold practicality of the reanimation world she later enters. Over the course of the story, Meka evolves from a sheltered girl haunted by dreams to a powerful, self-aware figure navigating the ethical weight of life, death, and resurrection.

Her final realization that she herself is the source of reanimation reframes the entire narrative: she is not simply the descendant of a legacy but a threshold between worlds, carrying the burden of choice and consequence.

Kassie Redwood

Kassie’s kindness, warmth, and motherly strength mask the truth that she is herself a reanimated being. Even before Meka learns this, Kassie is defined by resilience—managing chronic health issues, supporting the funeral home, and stabilizing a family shaped by secrecy.

After the revelation, every detail of her careful self-maintenance becomes tragic: the mortuary spray, the restrictions, the exhaustion. Kassie represents love that persists past death, yet she also embodies the horror of unnatural continuation.

Her relationship with Meka becomes even more tender and painful once the truth surfaces, as she balances the desire to protect her daughter with the exhaustion of a body that is no longer truly hers. Kassie’s final decision to ask for release is one of the story’s most devastating emotional beats.

It reflects her enduring selflessness and her refusal to allow her continued existence to become a burden or a corruption of love. In dying a second and final time, Kassie gives Meka a painful but necessary freedom.

Jonathan Redwood

Jonathan is emotionally awkward, fiercely intelligent, and weighed down by a legacy he never escaped. As a brilliant mortician and a reanimator, he exists in a dual identity—loving father and guardian of a dangerous, ancient craft.

His discomfort with the living and ease with the dead reflect both his personality and his history of loss, most notably Kassie’s death and resurrection. Jonathan’s fear of confrontation, secrecy about the book, and tense interactions with other reanimates reveal a man trying desperately to shield his family from the consequences of his past choices.

Yet he is also profoundly devoted to them. His willingness to sacrifice himself and his eventual decision to destroy the book demonstrate a tragic wisdom shaped by regret.

Jonathan is a man who loved too hard, meddled too deeply, and ultimately learned that some forms of power demand a price no family should have to pay.

Noah Cliff

Noah begins as a grounding force in Meka’s life—gentle, creative, devoted, and deeply connected to her. His sudden death fractures the story’s emotional foundation, plunging Meka into grief that mirrors the trauma of her childhood nightmare.

His reappearance as a reanimate complicates the tender simplicity of young love, transforming him from boyfriend into something both familiar and uncanny. Noah, however, remains emotionally sincere even after death.

His fear, shame, and longing to remain himself despite physical deterioration make him one of the most heartbreaking figures in the book. His refusal to become a monster contrasts sharply with the reanimates who embrace violence.

Noah’s final request to be let go reflects his humanity more than anything—he chooses dignity and peace over unnatural survival. His love for Meka lingers well beyond his body’s limits, shaping her journey long after he is gone.

Caleb

Caleb brings levity, warmth, and normalcy to Meka’s otherwise morbid world. His nervous humor and dramatic reactions—especially around the funeral home—highlight how unusual Meka’s upbringing is.

Caleb represents the innocence and grounded friendships of adolescence, a reminder of the life Meka might have lived without the shadow of reanimation. Though he is primarily a secondary figure, his presence reinforces Meka’s humanity at crucial moments.

Caleb’s fear, loyalty, and occasional panic serve as an emotional counterbalance to the darker forces at play.

Cipriana

Cipriana offers confidence, style, and sharp insight, often acting as the more socially attuned member of Meka’s friend group. She is observant and protective, especially in moments when strange men or unsettling events threaten the group’s safety.

Cipriana’s presence highlights themes of chosen family and the power of friendship in a narrative dominated by grief and monstrosity. She is one of the few people who gives Meka a sense of normal teenage life, even as that life slips further away.

Maxine Cliff

Maxine is a mother blinded by grief and denial, clinging desperately to normalcy even after her son’s death and reanimation. Her pain manifests as stubborn refusal rather than acceptance, causing friction with Noah and later placing everyone at risk.

Maxine symbolizes the human inability to release loved ones, mirroring Jonathan’s earlier desperation when Kassie died. Her denial is heartbreaking but deeply human, illustrating how grief can distort reality and lead to dangerous hope.

Camille, Morris, Roger, Langan (The Reanimate Collective)

These reanimates embody the corrupted side of resurrection—individuals who, unlike Kassie and Noah, lean into the monstrous nature of their second lives. Their patchworked bodies and reliance on scavenged parts underscore the horror of unnatural persistence.

Camille’s cool menace, Morris’s brutality, Langan’s instability, and Roger’s compliance reveal the various ways reanimated individuals cope with decay and identity loss. They follow the monster not out of loyalty but fear and necessity, driven by desperation to avoid disintegration.

As a collective, they contrast sharply with Meka’s family, illustrating the thin line between survival and monstrosity.

The Monster (Frankenstein’s Original Creation)

The monster is the origin point of centuries of suffering—a decaying, calculating, ancient being whose existence warps every life touched by reanimation. His body, stitched from centuries of replacements, is a grotesque monument to the horrors of immortality.

He represents manipulation, corruption of legacy, and the perversion of creation. His fixation on Meka stems from her bloodline and her potential; he sees in her the ultimate tool to escape decay.

His self-perception mixes superiority with bitterness, believing himself the pinnacle of reanimation while living in endless rot. The monster serves not only as an external villain but as a thematic warning: power without mortality becomes monstrosity.

His final destruction is both the end of a long horror and the beginning of Meka’s self-realization.

Grandpa Redwood

Though physically absent, Grandpa Redwood’s legacy and burial place become pivotal to the unraveling of the truth. His coffin shelters the book and the history of reanimators, and his past choices shape Jonathan’s path.

The decay of his unembalmed body reflects the family’s fraught relationship with death—both reverent and violated. His role as the keeper of the book links him directly to the generational burden Meka inherits, making him a quiet but powerful presence in the narrative.

Gerald

Gerald is an unsettling, flirtatious delivery man who adds tension to the Redwood household. His interest in Kassie creates discomfort, especially for Jonathan, and his presence highlights the vulnerability of a family living with secrets.

While he is not central to the supernatural plot, Gerald represents persistent outside pressures that threaten the fragile safety of the Redwood family even before their world unravels completely.

Themes

Identity, Origins, and the Fear of Inheritance

Meka’s sense of self is repeatedly tested as her life begins to fracture under the weight of hidden truths. Her recurring nightmare already positions her identity on unstable ground, suggesting a buried event that shaped her long before she could understand it.

As she uncovers the truth about her mother’s death, her own childhood resurrection, and her family’s secret lineage of reanimators, her understanding of who she is becomes tangled with a legacy she never asked for. The fear that she may inherit a power capable of reversing death forces her to question not only her origins, but also the boundaries of humanity itself.

The revelation that her mother has lived as a reanimate for most of Meka’s life complicates her memories, prompting her to wonder which parts of her life were authentic and which were held together by formaldehyde and mortuary wax. When the monster identifies her as the last and most potent descendant of Dippel, she confronts the possibility that her very existence is tied to an ancient lineage defined by experimentation, decay, and control.

Her identity becomes a battleground between what was chosen for her and what she chooses for herself. The final moments—when she realizes the power resides in her alone—force her into an uncomfortable awareness: that her essence cannot be separated from death, resurrection, and the ethical consequences of wielding such abilities.

This theme reaches its peak when she stands at Noah’s tomb, feeling the draw of her power. Her grief and longing blur with the intoxicating possibility of undoing fate, leaving her suspended between the person she wants to be and the destiny she fears she cannot escape.

Grief, Love, and the Desperation to Hold On

Grief permeates Make Me a Monster from the opening nightmare to the final confrontation at Noah’s tomb. Meka’s love for Noah is expressed through small details—late-night phone calls, shared secrets, and moments carved into the icy landscape of Ithaca Falls—but it becomes most visible when she loses him.

Her grief pulls her into a fog where reality bends. She thinks she hears him sigh in his casket, feels the echo of his presence in the memorial hall, and clings to the bracelet he gave her as if it were a lifeline.

The emotional devastation is further sharpened by the fact that her life is shaped around death; she prepares bodies, witnesses mourning families, and handles the stillness of corpses with practiced ease. Yet nothing in her work prepares her for personal loss.

When Noah reappears as a reanimate, her grief transforms into a complicated relief—because the boy she loved stands before her, breathing and speaking, yet permanently caught between life and death. This duality forces her to confront the ways love can become possessive or blinding when paired with desperation.

Her parents’ history mirrors this conflict: her father’s resurrection of her mother was rooted in profound love, but the result was a decade of hidden suffering, secret maintenance, and a life preserved through chemicals rather than vitality. The theme crescendos when both Kassie and Noah ask Meka to let them go.

Their acceptance of their fates contrasts with her desire to cling to them, revealing the emotional cruelty of reanimation. Ultimately, grief becomes both the weight that crushes her and the force that clarifies her choices.

When she destroys the book, she accepts that love cannot justify keeping someone trapped in an unnatural existence, even when her heart is breaking.

Death, Resurrection, and the Ethics of Power

The novel constructs a world where death is not a boundary but a permeable state, and this forces characters to examine what it truly means to be alive. Reanimation blurs the line between agency and control, especially when bodies are restored without consent and then manipulated, harvested, or reduced to tools.

Meka witnesses firsthand how the resurrected exist in a suspended condition—moving, thinking, and feeling, yet slowly deteriorating as their bodies reject the artificiality imposed upon them. Kassie’s daily maintenance becomes a painful reminder of the unnatural cost of resurrection: wax repairs, spray paint, stitched joints, and the gradual collapse of a body fighting decay.

Noah’s second life mirrors this instability, as each injury becomes a permanent mark that cannot heal. The underground network of reanimates, scavenging limbs and replacing their own, exposes how easily the power to resurrect can be corrupted.

Dippel’s monster stands at the apex of this corruption, using centuries of stolen vitality to exert control and enforce loyalty through fear. His existence demonstrates what happens when power is divorced from morality, and when reanimation becomes a means of ownership rather than salvation.

Meka is thrust into the center of this ethical dilemma when she performs her first resurrection without the book, realizing that her power may bypass the rituals that previously defined the limits of reanimation. The question ceases to be whether resurrection is possible and becomes whether it should be used at all.

By burning the book, she chooses responsibility over temptation, yet the pull of her ability remains unresolved. The final scene suggests a future in which she must confront the implications of wielding a power that disrupts the natural order, making the ethics of resurrection an ongoing and deeply personal struggle.

Family, Secrets, and the Weight of Protection

Family in the novel is built on love but maintained through secrecy. Meka grows up in a household where death is a familiar presence, yet the truth behind her mother’s condition remains hidden from her for years.

Her father’s choice to resurrect Kassie stems from heartbreak, but the long-term consequences create a home built on fragile foundations. Small inconsistencies—her mother’s allergies, her exhaustion, and her avoidance of doctors—become clearer once the truth surfaces, revealing how much effort went into shielding Meka from a reality too heavy for a child.

This desire to protect becomes a pattern. Kassie constantly worries about Meka’s nightmares, Jonathan panics at any perceived threat, and both of them make decisions that place Meka emotionally in the dark.

When the truth finally emerges, it is not a moment of betrayal but one of painful clarity. Meka understands why her parents hid the truth, yet she also feels the burden of becoming part of the lineage they attempted to manage alone.

Her parents’ love becomes both a sanctuary and a responsibility she never asked for. Even outside her immediate family, the theme extends to Noah and Maxine Cliff.

Maxine’s refusal to accept Noah’s death—and later his reanimated state—reflects a parent’s instinct to cling to the child they love, even when confronted with the impossible. Noah, caught between his mother’s denial and Meka’s grief, becomes a symbol of how protection can unintentionally cause harm.

The climax at Dundas Castle heightens these dynamics as Meka witnesses the ultimate cost of family loyalty: Kassie sacrifices the last of her strength to save her daughter, and Jonathan risks his life to keep the book out of monstrous hands. Family becomes both the anchor that holds Meka steady and the chain that ties her to a legacy of danger, secrets, and irreversible choices.

Corruption of Science and the Pursuit of Power

The world of reanimation begins as a secretive family practice but expands into a network of individuals willing to sacrifice ethics, bodily autonomy, and humanity itself for the sake of power. The reanimates who stalk Meka and her family see bodies as replaceable parts, scavenging limbs and organs without regard for the original person.

Their methods reduce human beings to raw material, turning science into a predatory enterprise. The monster, created centuries earlier, embodies the ultimate corruption: a being who was born from experimentation and then perpetuated suffering through manipulation and intimidation.

His influence on generations of reanimators shows how scientific knowledge can metastasize when divorced from moral grounding. Jonathan’s more restrained use of the practice highlights the contrast between science used to heal and science used to dominate.

Although his resurrection of Kassie is ethically fraught, his intentions are rooted in love rather than exploitation. However, the consequences reveal that even well-meaning applications can birth long-term suffering.

The stolen book becomes a symbol of temptation, offering the possibility of transcending death while demanding a steep cost. Meka’s ability to reanimate without it raises the stakes, suggesting that the potential for corruption lies not just in texts or rituals but within individuals themselves.

This theme culminates in the destruction of the book, where the characters confront the choice between advancing a dangerous scientific legacy or dismantling it entirely. Yet even in its destruction, the residue of power remains within Meka, leaving the theme unresolved in a way that mirrors real-world tensions between discovery and ethical restraint.