Replaceable You Summary and Analysis

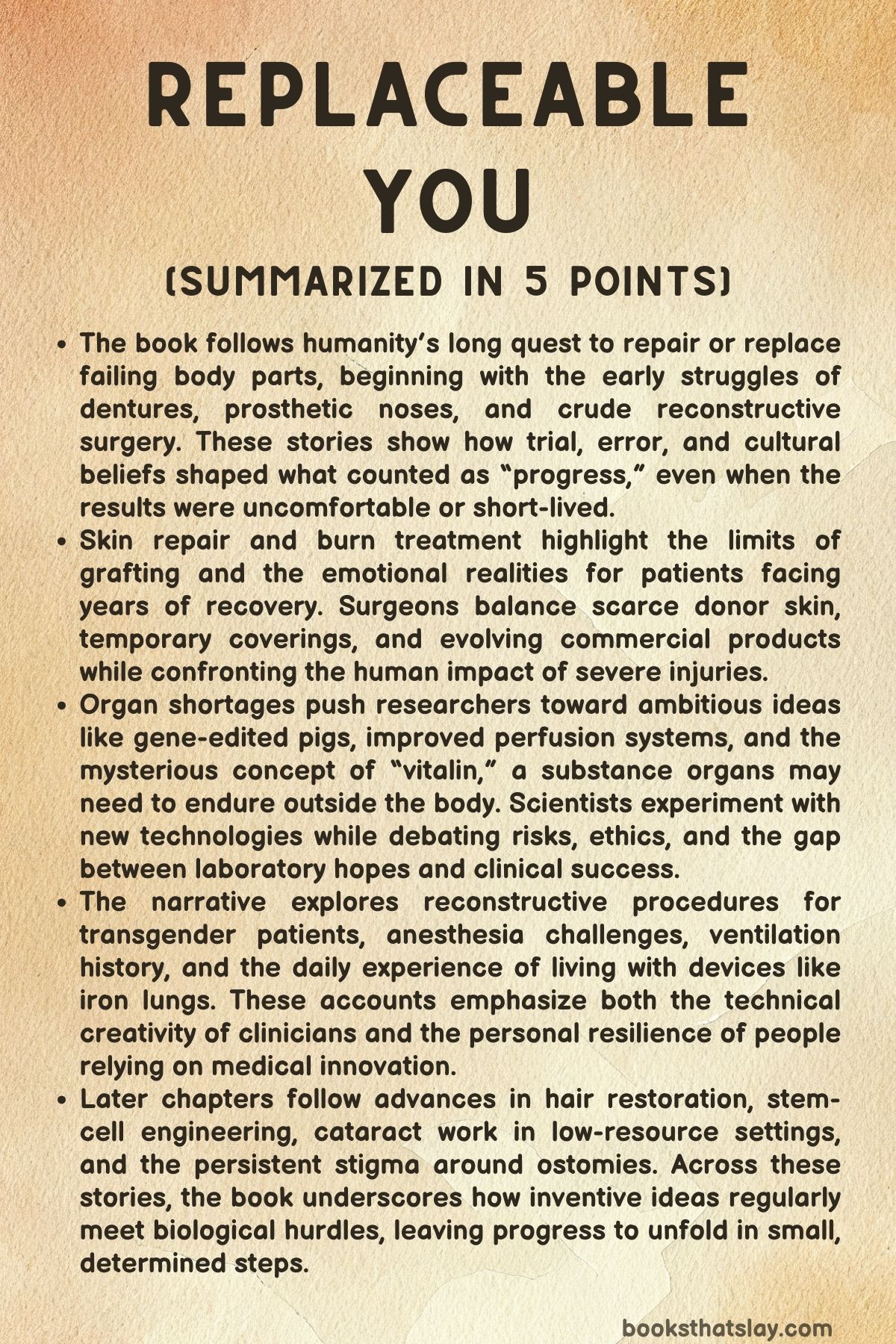

Replaceable You by Mary Roach is an exploration of humanity’s ongoing attempts to repair, rebuild, and reinvent the human body. Roachm moves through centuries of medical improvisation, from crude Victorian chewing devices to the frontiers of organ growth, reconstructive surgery, and stem-cell engineering.

Through vivid reporting, scientific inquiry, and dark humor, she examines the messy trial-and-error behind each breakthrough and the people pushing these fields forward. The book follows surgeons, researchers, patients, and even pigs, showing how solutions to medical problems often emerge slowly, unevenly, and with unexpected complications. It is an investigation of what it takes to keep a body working when nature alone falls short.

Summary

Replaceable You traces humanity’s long effort to repair the human body, beginning with teeth, noses, and skin before moving into modern transplant science, regenerative medicine, and experimental reconstruction. The narrative opens in the Victorian era, when many adults lacked functional teeth and relied on awkward solutions such as handheld masticators—small metal tools used to pre-chew food.

Early dentures were often decorative and unstable, sometimes spring-loaded in ways that caused them to shoot out of a wearer’s mouth. Even into the twentieth century, dentures were uncomfortable enough that many younger adults chose to have all their teeth removed rather than endure ongoing dental procedures.

After teeth, the book turns to noses, beginning with Tycho Brahe, who wore a prosthetic after losing part of his nose in a duel. Materials and attachment methods improved over the centuries, though early prostheses remained unreliable.

Long before prosthetics, ancient Indian surgeons created replacement noses using cheek or forehead flaps, a technique that resurfaced in Europe during the Renaissance. Gaspare Tagliacozzi advanced these procedures with arm-flap rhinoplasty, which required weeks of immobilization.

Earlier innovators such as Heinrich von Pfalzpaint experimented with grafting and emphasized cleanliness at a time when sterile technique did not yet exist. Success rates were low, scarring was common, and attempts to use animal tissue rarely worked.

The discussion moves to skin grafting and burn care. At Massachusetts General Hospital, surgeon Jeremy Goverman explains that the best grafts come from the patient but are limited by available uninjured skin.

Temporary coverings from cadavers or animals protect against infection and fluid loss. Historical reports of animal grafts “taking” for short periods are now understood as effects of burn-induced immune suppression.

The text follows the story of Diana Tenney, a burn survivor whose long recovery illustrates the difficulty of managing severe burns, preventing contractures, and performing repeated surgeries. Her experiences show how restoring function can take years of grafting, scar releases, and therapy.

The book then examines global shortages in human organs and recent progress in xenotransplantation. In China, organ donation is limited by cultural beliefs, leading to investment in gene-edited pigs.

By removing the α-gal gene, researchers have prevented immediate immune rejection, allowing pig kidneys and hearts to function for days or weeks in human recipients. These early procedures are viewed as potential bridges for patients awaiting full transplants.

Facilities maintain highly controlled pig populations bred specifically for medical use. Alongside this work, scientists are exploring chimeric animals that might one day grow human organs, although ethical concerns arise when human cells appear in unintended tissues.

Other research focuses on treating diseases such as diabetes using encapsulated pig islet cells, which could release insulin without provoking immune attack.

A major portion of the narrative follows the University of Michigan’s Extracorporeal Life Support Lab, where Bob Bartlett and his team explore how to keep hearts alive outside the body. Experiments use perfusion pumps designed to extend the viability of donor organs well beyond the current eight-to-twelve-hour window.

Readers observe a pig-heart extraction, the challenges of preventing arrhythmias, and the difficulty of maintaining blood flow through artificial tubing. The team tests nitric-oxide–infused tubing to reduce clotting and studies how hearts respond during long perfusion runs.

Bartlett proposes the existence of a mysterious brain-derived substance, which he calls vitalin, that appears necessary for long-term heart function. Evidence from brain-dead patients and rare medical cases supports the theory, though the substance itself remains unidentified.

Bartlett’s background in ECMO leads to broader discussions about life-support technologies. Modern mobile ECMO units can rescue cardiac-arrest patients within minutes.

The team dismisses alternate oxygenation methods such as enteral ventilation via the anus, noting that though others pursue such experiments, results remain limited.

The book next examines transgender reconstructive surgery at Cedars-Sinai, where surgeon Maurice Garcia specializes in intestinal vaginoplasty for trans women. When penile-inversion surgeries produce complications or insufficient depth, Garcia and a colorectal surgeon use a segment of ascending colon to create a new vaginal canal.

He explains the advantages and risks of bowel-based tissue, including mucus production, nutrient needs, and potential inflammation. The text describes neoclitoral construction, placement limitations, and the reasons many patients choose external-only vulvoplasty.

Garcia also treats trans men seeking corrections to overly large surgically constructed penises, noting historical problems in which earlier surgeons favored exaggerated dimensions. His work is contrasted with accounts of extreme reconstructive attempts, such as using a patient’s finger bone to form penile structure.

The story shifts again to anesthesia and breathing. At Stanford, anesthesiologist Jordan Newmark describes the risks inherent in intubation, especially when paralytic drugs halt breathing.

Training on a manikin reveals how easy it is to misplace the tube, damage teeth, or accidentally inflate the stomach. Despite these hazards, anesthesia remains safe due to extensive training and improved ventilator systems.

The narrative moves through the history of breathing machines, from iron lungs used during polio outbreaks to modern positive-pressure ventilators. A visit to Kansas City shows the daily life of Mona Randolph, who lived for decades supported by an iron lung and daytime sip breathing.

Experts discuss the drawbacks of long-term positive-pressure ventilation and the search for hybrid systems that reduce lung injury.

From breathing devices, the book travels to Mongolia with Orbis International, where ophthalmologists train local surgeons in manual small-incision cataract surgery. The narrative follows the operation step by step, emphasizing its affordability and reliability in regions where high-tech methods are impractical.

A herder’s rapid improvement after surgery illustrates the life-changing impact of these procedures. The discussion broadens into global cataract treatment and the challenges of creating artificial lenses that fully accommodate like a natural one.

The topic then turns to ostomies and the stigma surrounding them. Historical appliances were crude, but modern ostomy pouches allow people with inflammatory bowel disease or incontinence to regain normal lives.

At an Ostomy Awareness 5K, participants share stories of improved health and the misconceptions they face. Attempts to engineer artificial sphincters—hydraulic cuffs, magnetic rings, or lab-grown structures—have not yet produced a dependable replacement.

Later chapters follow a hair-transplant experiment that sends the narrator’s follicles to Stemson Therapeutics for stem-cell research. Scientists attempt to grow new follicles using induced pluripotent stem cells, though progress is slow and the company eventually closes.

The story expands to the broader stem-cell marketplace, calling out cosmetic and unregulated therapies that lack scientific support and sometimes cause serious harm.

The book closes with scenes from tissue-recovery suites, experimental cosmetic reshaping using fat, and reflections on how even simple biological structures resist replication. An epilogue notes halted research projects, incremental successes in xenotransplantation, and updates on individuals involved in earlier chapters.

Through each topic, Replaceable You reveals how restoring the human body remains a mix of innovation, persistence, and frequent setbacks, as medicine continually tries to match the complexity of human biology.

Key People

Jeremy Goverman

Jeremy Goverman appears as a modern plastic surgeon whose work at Massachusetts General Hospital centers on burn treatment and the intricate science of skin grafting. He represents both the precision and limitations of reconstructive medicine: a practitioner who must navigate the narrow space between what is technically possible and what a patient desperately needs.

Through his explanations, he embodies the rational, methodical mind of a surgeon who understands not only the mechanical aspects of grafting but also the physiological fragility of severely burned bodies. His character highlights a medical worldview grounded in practicality, patience, and an unembellished realism about the body’s capacity to heal.

Goverman’s interactions demonstrate a clinical compassion, revealing a personality shaped by exposure to extreme trauma and the slow, repetitive process of reconstruction.

Diana Tenney

Diana Tenney emerges as a deeply human and emotionally resonant presence in the narrative, a survivor whose story brings the science of burn care into intimate focus. Her long, painful journey through dozens of grafts, surgeries, and years of forced adaptation reveals her extraordinary endurance.

Yet her character is not reduced to perseverance alone; she is portrayed as someone who must renegotiate her identity and sense of self after catastrophic injury. Diana illustrates how trauma reshapes the boundaries between body and personhood, becoming a living testament to the psychological costs of survival.

Her story grounds the book’s scientific themes in real human experience, showing that behind every technological innovation is someone who must live with its imperfect outcomes.

Bob Bartlett

Bob Bartlett, the pioneering surgeon behind ECMO, is depicted as a spirited, intellectually restless elder statesman of medical innovation. Even at eighty-five, he leads research at the University of Michigan with a hands-on enthusiasm that borders on youthful.

Bartlett embodies curiosity, resilience, and a near-playful boldness as he discusses experimental ideas such as “vitalin,” a theorized brain-derived substance that sustains organ longevity. His character blends the roles of mentor, maverick, and visionary, anchored by decades of witnessing both breakthrough and failure.

Bartlett serves as a narrative bridge between medicine’s past and future, symbolizing the drive to stretch scientific boundaries far beyond their assumed limits.

Wyeth Alexander

Wyeth Alexander, the surgeon-in-training who assists in the removal and revival of pig hearts, symbolizes the next generation of medical innovators. In the narrative, he is meticulous but still learning, balancing competence with moments of hesitation—such as when the heart slips into arrhythmia and must be corrected.

His character reflects the tension between confidence and vulnerability that accompanies the steep learning curve of high-stakes surgery. Wyeth’s presence underscores the importance of mentorship, teamwork, and steady nerves, capturing the emotional reality of becoming a surgeon in fields where one wrong move can compromise an organ’s viability.

Dan Drake

Dan Drake works alongside Wyeth as another member of the surgical team, offering a steadier, more seasoned complement to the trainee’s energy. His role, though less dramatized, adds depth to the depiction of surgical collaboration.

Drake represents the quiet expertise essential to experimental medicine—someone who understands that pioneering science is built not only on bold ideas but also on the unglamorous work of precision, protocol, and vigilant observation. Through him, the narrative reinforces the theme that cutting-edge progress relies on collective competence rather than solitary genius.

Maurice Garcia

Maurice Garcia stands out as an empathetic and meticulous urologist specializing in gender-affirming surgery. His work in intestinal vaginoplasty is marked by technical rigor and ethical commitment, and he emerges as a character who insists on thoughtful innovation rather than reckless experimentation.

Garcia is portrayed as someone who listens closely to patients, acknowledges the physical and emotional complexities of transition-related surgeries, and confronts the long legacy of harmful medical practices inflicted on transgender individuals. His character embodies medical advocacy—practical, skeptical, and deeply concerned with preserving dignity and function for his patients.

Jordan Newmark

Jordan Newmark, the anesthesiologist, brings a mix of calm authority and educator’s patience to the chapter on intubation. He serves as a guide into the hidden risks behind a procedure most patients take for granted, revealing the razor-thin margin of error in airway management.

Jordan’s character is defined by his ability to translate a high-risk, high-pressure field into approachable terms while maintaining a realistic awareness of its dangers. His presence highlights the vital but often invisible role anesthesiologists play in modern surgery, where the line between routine procedure and crisis is precariously thin.

Mark Randolph

Mark Randolph enters the narrative through his late wife Mona’s history with the iron lung. His character radiates devotion, steadiness, and quiet resilience as he recounts the logistics, emotional strain, and daily rituals required to care for a partner dependent on cumbersome technology.

Mark becomes a portrait of love shaped by long-term caregiving: a person who preserved intimacy and partnership despite profound physical limitations imposed by polio. His reflections lend emotional depth to the book’s exploration of respiratory devices, turning mechanical concepts into deeply lived experience.

Enkhzul Damdin

Enkhzul Damdin, the Mongolian cataract surgeon, embodies resourcefulness and global medical equity. Working in an environment with limited technology, she performs manual cataract surgeries that restore sight to patients who might otherwise remain blind.

Her character reflects a disciplined commitment to mastering delicate techniques, such as capsulorhexis, without the aid of advanced equipment. Enkhzul represents the many surgeons worldwide who perform life-changing procedures under constrained conditions, revealing that medical progress is not always synonymous with high-tech tools but often with skill, adaptability, and determination.

Dave Rudzin

Dave Rudzin, the long-time ostomate and advocate, stands as a symbol of openness, humor, and the fight against stigma. His character helps demystify ostomy life by addressing misconceptions, fears, and social prejudice head-on.

Through his conversations, he transforms what many people view as a taboo subject into an everyday reality filled with practical adaptations and personal empowerment. Dave’s presence reinforces one of the book’s recurring themes: that medical interventions often succeed not only because of technology but because of the resilience and attitude of those who live with them.

Richard Chaffoo

Richard Chaffoo, the hair-transplant surgeon, plays a lively and somewhat comedic role in the chapter on follicle harvesting. He is skilled yet occasionally flustered, portrayed with affectionate irony as he wrestles with the placement of a single follicular unit into the narrator’s calf.

His character blends surgical confidence with moments of human imperfection, providing levity while also highlighting the technical precision required in cosmetic procedures. Chaffoo stands as a gateway figure between traditional surgical practice and the futuristic ambitions of regenerative hair science.

Antonella Pinto

Antonella Pinto appears briefly but memorably as the Stemson scientist who races against time to deliver the narrator’s harvested follicles to the lab. She embodies the urgent, almost breathless pace of research where viability can degrade minute by minute.

Her character represents dedication, speed, and the logistical demands of cell-based biotechnology. Though she later departs the company, her role underscores how fragile research trajectories can be, dependent on individuals working under pressure to keep experiments alive—literally and figuratively.

Kevin D’Amour

Kevin D’Amour, Stemson’s chief scientific officer, brings intellectual steadiness and clarity to the complicated world of induced pluripotent stem cells. He is portrayed as a thoughtful explainer, grounding advanced concepts in accessible language while maintaining transparency about scientific setbacks and uncertainties.

D’Amour’s character exemplifies the scientist who balances ambition with realism, acknowledging failures without losing sight of long-term possibilities. His presence illustrates the tension between scientific hope and the harsh economics of biotech research.

Lisa McDonnell

Lisa McDonnell serves as a key researcher guiding the narrator through the cell-culture process, embodying the careful, methodical labor behind regenerative biology. Her character highlights the repetitive precision of tissue culture work, where progress depends on days and weeks of tending cells through complex differentiation stages.

Lisa represents the unglamorous backbone of biotechnology—the patient, quiet expertise that underlies every potential breakthrough. Through her, the narrative emphasizes that revolutionary science often rests on the hands of people whose work remains largely unseen.

Analysis of Themes

The Human Body as Both Fragile and Ingenious

Across Replaceable You, the human body emerges as something that fails easily and yet demonstrates astonishing complexity, pushing medicine to innovate while constantly reminding practitioners of biological limits. The accounts of Victorian tooth loss, disfiguring burns, failing organs, and congenital or acquired anatomical challenges underscore how quickly ordinary life can be disrupted by bodily malfunction.

Yet this fragility is not portrayed as defeat; instead, it becomes the catalyst for centuries of creative problem-solving. Tooth substitutes evolved from crude shears and spring-loaded contraptions to functional prosthetics.

Rhinoplasty progressed from forehead-flap grafts that required weeks of bodily tethering to modern reconstructive techniques. Burn care advanced from primitive temporary skins to nuanced strategies for protecting wounds, balancing immune responses, and preserving mobility.

Each example demonstrates how human vulnerability motivates relentless attempts to restore form and function. At the same time, the body’s ingenuity frustrates those efforts.

Immune rejection, contractures, clotting, the complex physics of breathing, and the subtleties of hormone-mediated organ viability reveal how deeply optimized human physiology is and how difficult it is to reproduce or modify. Even hair follicles, seemingly simple structures, resist laboratory recreation.

The theme rests not only in biological limitation but in the tension between what fails and what functions too precisely to be easily replaced. Medicine is shown as a long negotiation with this dual nature, always trying to keep pace with a system that can collapse quickly yet is too specialized to rebuild easily.

Innovation Built on Trial, Error, and Bold Experimentation

The narrative demonstrates over and over how progress in medicine rarely follows a straight line. Many pivotal advances arise from half-successful ideas, crude prototypes, or approaches that now seem misguided.

Animal-skin grafts, early perfusion pumps, primitive dentures, and early cataract techniques all reflect periods when practitioners relied on intuition and improvisation more than formal research. The pig-heart experiments in the ECLS lab continue this tradition, tinkering with flow rates, tubing coatings, and perfusion strategies to extend viability by mere hours.

Xenotransplantation represents another iteration of this experimental mindset, where scientists attempt gene edits, immunological tweaks, and containment strategies that may yield only incremental gains. In surgical reconstruction, the same pattern appears: ascending-colon vaginoplasty, resizing phalloplasties, and the use of finger bones for penile reconstruction show how surgeons adapt existing materials—including the patient’s own tissues—in novel ways.

Stemson Therapeutics’ attempts to cultivate hair follicles, whether through biodegradable tubes or self-assembled structures on sutures, similarly reflect how progress depends on persistence through repeated setbacks. This theme highlights how much of modern medicine is shaped by imperfect prototypes that gradually refine techniques now taken for granted.

Innovation is shown not as a series of triumphs but as a long continuum of attempts where failure is expected, patience is essential, and breakthroughs often look eccentric in their earliest forms.

Cultural Beliefs, Stigma, and the Social Dimensions of Medicine

The text consistently reveals how culture and perception shape medical decision-making just as profoundly as biological necessity. Victorian attitudes toward dental aesthetics led people to remove healthy teeth because dentures were viewed as modern and glamorous.

In China, Confucian values surrounding bodily integrity deepen organ shortages, pushing the country to explore gene-edited pigs as an alternative. The experiences of transgender patients reflect how social norms, surgical biases, and the legacy of medical gatekeeping have influenced the quality and availability of gender-affirming procedures.

The discussions of ostomies expose how stigma causes many to fear or avoid life-saving surgery, while those living with stomas describe greater freedom and relief than outsiders assume. Even polio survivors’ memories of iron lungs differ depending on emotional context, support networks, and the public’s perception of disability.

Cultural forces extend into the commercialization of “stem cell” beauty products and unregulated treatments fueled by public fascination rather than evidence. In each case, medicine operates not in a vacuum but in a social environment where beliefs, shame, identity, and misinformation direct choices as strongly as science does.

This theme shows that progress requires not only technical skill but also dismantling the cultural obstacles that determine who receives care, what treatments are pursued, and how patients experience life after intervention.

Ethical Boundaries and the Question of How Far Medicine Should Go

Throughout the narrative, advances in bodily replacement raise profound ethical questions. Xenotransplantation and chimeric organ generation challenge assumptions about species boundaries, consent, and the moral status of animals engineered to serve as organ hosts.

The possibility that human cells might migrate into a pig’s brain forces researchers to weigh potential neurological implications that extend beyond clinical utility. Gender-affirming surgeries prompt reflection on past eras when surgeons imposed aesthetic norms or pursued personal curiosity at patients’ expense.

Unregulated stem-cell treatments reveal how commercial interests can exploit scientific vocabulary while exposing patients to serious risks. Even historical examples—such as arm-flap rhinoplasty or dubious animal-skin grafts—highlight how medical ambition has long walk a line between innovation and harm.

The tissue-recovery suite scenes and the discussion of “vitalin” raise additional issues surrounding brain death, organ donation, and the moment when a body transitions from patient to biological resource. This theme underscores how progress demands not only technological capability but a rigorous framework for determining when an intervention is justified, what risks are acceptable, and how to balance human benefit against ethical cost.

Medicine’s frontier is shown as a place where possibility is expanding faster than society’s consensus about what should be done.

The Emotional and Psychological Experience of Medical Intervention

Amid technical descriptions and scientific detail, the narrative repeatedly returns to the lived experiences of patients navigating pain, identity shifts, and loss. Burn survivor Diana Tenney’s story illustrates the trauma, prolonged rehabilitation, and emotional unpredictability that follow severe injury.

Polio survivor Mona’s life inside and outside the iron lung shows the intimate negotiations between disability, autonomy, and love. Transgender patients seek surgeries not simply for functional reasons but to align their bodies with their sense of self, pursuing outcomes that support comfort, dignity, and identity.

Ostomates describe the psychological journey from fear and social apprehension to relief and empowerment once their health stabilizes. Even the narrator’s small hair-graft experiment captures the vulnerability involved when the body becomes a site of scientific exploration.

This theme emphasizes that medical procedures ripple far beyond their technical success. They reshape relationships, challenge personal resilience, and alter how individuals understand their own bodies.

The narrative gives weight to these inner landscapes, illustrating that healing is not only anatomical but emotional, and that the true measure of an intervention often lies in how it affects the patient’s daily life, confidence, and sense of possibility.

The Limits of Technological “Replacement”

One of the book’s central ideas is that replacing a body part is rarely straightforward, no matter how simple it appears. Teeth, noses, skin, hearts, lungs, corneas, and even hair share a complexity that defies easy substitution.

The evolution of dentures shows how difficult it is to recreate the biomechanical subtleties of chewing. Rhinoplasty reconstructs form but cannot perfectly replicate original tissue behavior or sensation.

Skin grafts and artificial coverings struggle to perform the diverse roles of natural skin, from immune defense to elasticity. Ventilators assist breathing but cannot mimic the synchronized interaction of diaphragm, lungs, and neural control.

Heart perfusion technologies extend viability but cannot provide the hypothalamic factors organs seem to require. Cataract surgery restores sight but cannot replicate the accommodating abilities of the natural lens.

Hair follicles resist lab replication despite advances in stem-cell science. Artificial anal sphincters attempt to recreate continence but have not matched the reliability of a natural system refined by evolution.

The theme demonstrates that the human body is not a collection of parts that can be swapped like machine components; each structure is embedded in a network of biochemical and mechanical relationships. Medicine can approximate, assist, and compensate, but complete replacement remains elusive.

This limitation explains why progress is slow and why researchers continue seeking approaches that work with the body rather than merely standing in for it.