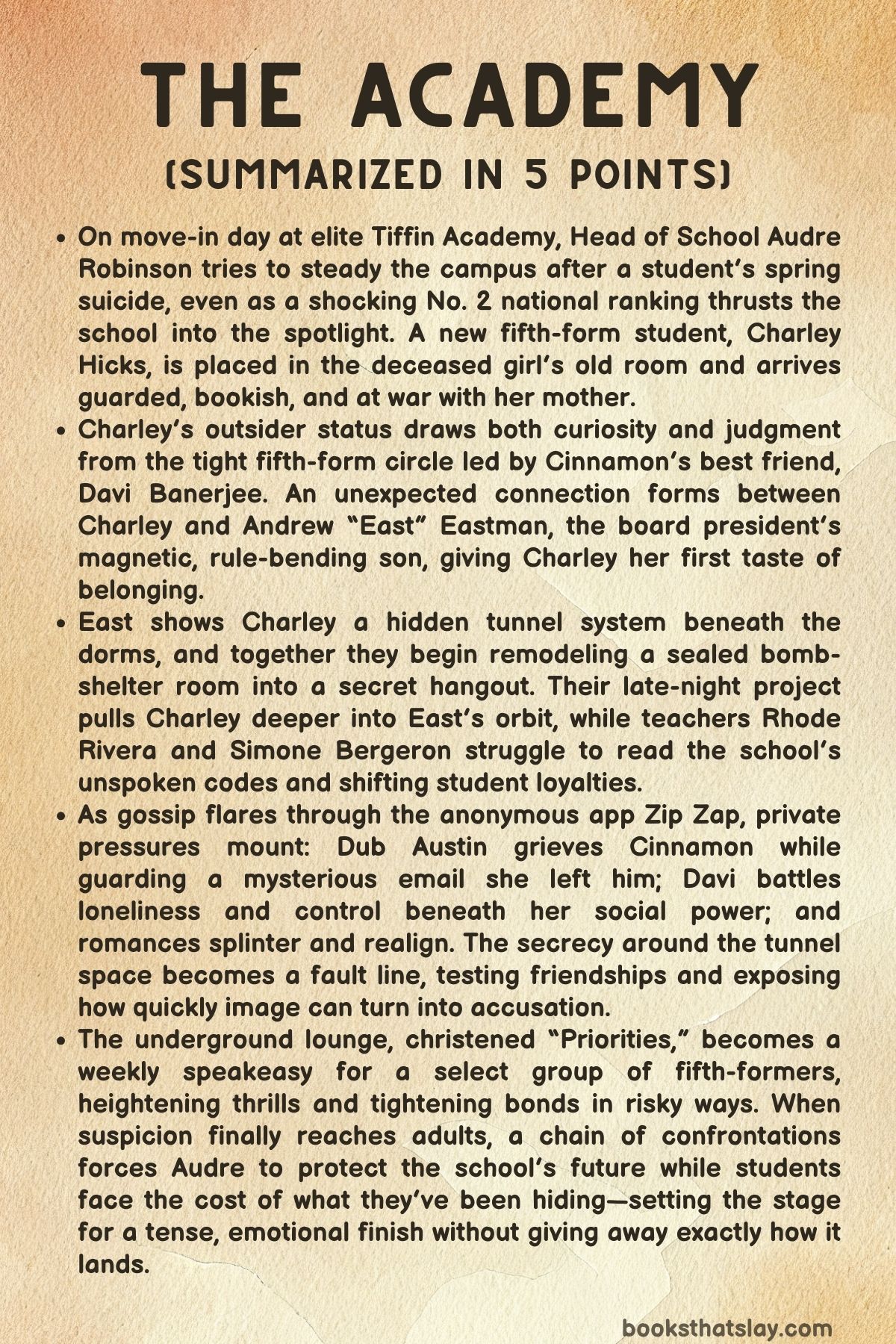

The Academy by Elin Hilderbrand Summary, Characters and Themes

The Academy by Elin Hilderbrand is a contemporary boarding-school novel set at elite Tiffin Academy in Vermont during a year when the campus is still raw from a student’s suicide. The story follows a web of students and teachers trying to hold themselves together while navigating ambition, grief, desire, and power.

At the center are a new girl placed in the dead student’s room, a quarterback haunted by loss, a queen-bee best friend stuck between loyalty and reinvention, and a head of school determined to protect both kids and reputation. It’s a fast, character-driven look at how a closed community handles trauma and temptation.

Summary

Tiffin Academy opens its fall term under a complicated cloud. Audre Robinson, the head of school, greets families on move-in day while privately replaying the spring tragedy: Cinnamon Peters, a fifth-former, died by suicide in room 111 South.

Audre is still shaken, hyperaware of every student’s mood, and especially protective of Cinnamon’s classmates. She also knows the America Today boarding-school rankings are about to drop, and the school’s powerful board president, Jesse “Big East” Eastman, expects proof that his donations have pushed Tiffin into the national spotlight.

Students arrive in waves. Webber “Dub” Austin, star quarterback, returns with his mother and a framed photo of himself with Cinnamon, his late girlfriend.

Dub is quiet, carrying grief that feels stuck in his chest. Davi Banerjee, Cinnamon’s best friend and the most socially influential girl at school, arrives looking ready to reclaim her place at the center of attention, even as her loss hovers close.

Audre notices Andrew “East” Eastman, Jesse’s son, pulling onto campus in his truck as if rules don’t apply; Audre worries about him because disciplining East could jeopardize the funding that keeps Tiffin thriving.

New faculty also step into the mix: Rhode Rivera, a former student returning as an English teacher, and Simone Bergeron, a young history teacher and dorm parent. The final move-in arrival is Charlotte “Charley” Hicks, admitted late after Cinnamon’s death opened a place in fifth form.

Charley comes from a troubled home situation, is bookish, blunt, and unconcerned with fitting in. She shows up in traditional preppy clothes, carrying stacks of classics and a jungle of houseplants.

Her mother, Fran, clearly hates leaving her there. Audre escorts them to 111 South—the room tied to tragedy—and watches a tense goodbye unfold.

Charley blames Fran for sending her away, Fran collapses into tears, and Charley storms out alone.

Minutes later Audre checks the rankings and sees Tiffin has leapt to number two in the country. The news explodes across campus.

At the all-school meeting, Audre announces the rise from nineteenth to second; students scream, film, and celebrate as if the ranking is a fresh start after the death that shadowed last year. At the cookout by Jewel Pond, everyone rides the high.

Charley sits apart reading, watched by girls who can’t decide if she’s fearless or strange. East, arriving late, chooses her side of the beach.

He talks her into swimming, and Charley reveals real talent, racing him across the pond. Her performance jolts the group’s perception of her.

East seems impressed and intrigued, while Davi reads the scene with suspicion, wondering if East is only using Charley for help or novelty.

The school adopts a brief era of “perfect behavior. ” Tiffin wins a historic football game, Dub becomes a campus hero again, and traditions come back with a force that feels like collective denial.

Yet underneath the cheeriness, grief and pressure linger. Dub carries a secret Cinnamon left behind: an email sent right before she died with an attachment labeled for him to open on graduation morning.

He has promised himself not to look, but the file feels like a locked door waiting in his pocket. Davi tries to keep moving in public, but her private life is fraying, and her bond with Cinnamon’s memory shapes every decision.

First Dance night becomes the first serious test of the new year. Davi learns Charley is skipping it and heads to room 111 with the required neon class dress to pull her in.

The visit triggers her memory of the morning Cinnamon died, the jammed door, and the helpless waiting in the hallway. Inside, Charley is calm, surrounded by books and plants, unimpressed by fifth-form rituals.

She rejects the dress and the dance, refusing to perform for anyone. Davi leaves annoyed but oddly respectful, newly curious about Charley’s stubborn independence.

While the neon party rages, Audre notices Charley missing and sends Simone to check on her. Charley isn’t in her room, and Simone grows anxious, fearful of repeating the past.

Charley has actually let East in through her window. He leads her into the dorm basement and down a hidden tunnel he discovered in old renovation plans.

They reach a soundproof bomb-shelter room fitted with bunks, water, and electricity. East is thrilled.

He imagines turning it into a secret hangout and wants Charley as his partner because she isn’t trapped by Tiffin’s social script. Footsteps approach; East sends Charley through the north exit while he stays behind.

In the tunnel Simone runs into East. He flirts, then crosses a line by kissing her.

She freezes, then pulls away just as Rhode appears with a flashlight, calling her name. East slips into darkness.

Simone, rattled and ashamed, returns upstairs and finds Charley already back in bed, coolly claiming she only went for coffee. Simone backs off, unsettled by how quickly things turned upside down.

As fall settles in, Charley and East begin meeting regularly in the tunnel, quietly transforming the shelter into a Jazz Age lounge. The secrecy is intoxicating for Charley, who feels more alive down there than anywhere else on campus.

East confides that he’s smart but bored, resistant to school, and planning a post-graduation business path instead of college. Charley finds his confidence magnetic.

Their flirtation turns into a slow build of tension, interrupted by Charley’s nerves and by her declining trust in people.

Simone, meanwhile, spirals. She drinks too much, feels insecure as a new teacher, and becomes emotionally tangled in East’s attention.

When he asks for private tutoring, she agrees, trying to be responsible. Instead, East comes to her classroom at night, shuts the door, and initiates sex.

Simone, already tipsy, lets it happen and then collapses into panic and self-loathing once he leaves. In the wake of that mistake, she accepts a date with Rhode, who is openly infatuated with her.

The date is extravagant and awkward, fueled by champagne and Haz Flanders’s gourmet food at a rented lakeside cottage. Simone drinks to numb herself, gets sick, and the night ends in humiliation for both of them.

Student relationships twist too. Hakeem Pryce chases Ivy recruitment while cheating on his girlfriend Taylor Wilson.

Taylor, feeling stuck and needy, drifts toward Dub. She and Dub bond over music nights, and she presses him to sleep with her, hoping to rewrite her own story.

Gossip app Zip Zap amplifies every rumor. Posts mock Haz for gambling losses and expose Taylor’s pursuit of Dub, poisoning friendships and pushing Audre to worry about the school’s emotional climate again.

As winter arrives, East and Charley finish their shelter makeover. With help from Haz—quietly supplying liquor—East opens the speakeasy, Priorities, inviting a tight inner circle of fifth-formers including Davi, Dub, Taylor, Hakeem, Madison J.

, and a few others. Phones are confiscated at the door, cocktails are served, and Saturday nights become their secret ritual for seven weeks.

The room feels like their own hidden world beneath Tiffin’s polished surface. Bonds shift inside it: Taylor and Hakeem fall back into each other, Dub watches with quiet hurt, and Charley grows closer to the group but remains aware that she has the least protection if things collapse.

The secret unravels because of exclusion. Olivia H-T, a younger student hungry for status, notices suspicious late-night absences, checks rooms at 1:30 a.

m. , and realizes the fifth-form leaders are sneaking out together.

Furious at being shut out, she reports her suspicions to Simone. Simone, bitter and unstable, immediately guesses Priorities is East’s project.

Drunk and reckless, she storms to East’s room, grabs a key, and drags Rhode to the tunnel. When they unlock the speakeasy, the alcohol is gone—East has cleared evidence.

Still, Simone insists on taking the story to Audre.

Instead of triumph, Simone meets ruin. Audre is summoned by a senior administrator who plays her East’s recording: proof of Simone’s sexual involvement with a student.

Simone admits the relationship and tries to redirect blame onto East, then leads Audre to Priorities. Audre is shocked by the lavish hidden room but sees only a stray swizzle stick as physical proof.

She fires Simone on the spot, choosing institutional survival over public chaos. Simone also claims Honey Vandermeid, the college counselor, made an unwanted advance toward her.

Honey admits it, resigns, and leaves, breaking Cordelia Spooner’s heart and adding another fracture to the adult community.

The fallout hits students hard. Charley learns East slept with Simone and feels manipulated.

She blocks him and shuts down, turning to Davi for support. Davi, for all her sharp edges, steps into loyalty, helping Charley steady herself.

East keeps trying to apologize, but trust is thin. Audre shuts Priorities down quietly and avoids punishing East beyond that, knowing his father’s influence could end her tenure and the school’s funding.

She also suspects Haz’s involvement but decides not to dig, wary of triggering another scandal.

The year closes on Prize Day with the usual ceremony masking everything that happened underneath. Charley stays distant from East during formal events, but Davi guides her to the library’s Senior Sofa where the Priorities group gathers one last time.

East approaches, asking to sit. After a tense pause, Charley makes space beside her.

It’s not a clean forgiveness, more a cautious acknowledgment that their story isn’t finished and that, despite betrayal and secrecy, they shaped each other’s year at Tiffin. The campus moves on, carrying its triumphs, guilt, and quiet bargains into the next term.

Characters

Audre Robinson

Audre Robinson, the head of school at Tiffin Academy, is the emotional and ethical center of The Academy. She begins the year still raw from Cinnamon Peters’ suicide, and that grief shapes almost every choice she makes: she is vigilant, protective, and quietly haunted by the idea that another student could slip through the cracks.

Audre’s public face is polished competence, but privately she is anxious about reputation, rankings, and the expectations of the board, especially with Jesse “Big East” Eastman looming over the institution through money and influence. Her conflict is constant: she wants to be a moral educator and steward of student well-being, but she also must keep the school afloat in a world where prestige and donor satisfaction can outweigh justice.

That tension peaks when she discovers Priorities and Simone’s misconduct. Audre acts decisively in firing Simone and shuttering the speakeasy, yet her decision to largely shield East reveals her pragmatism and frailty: she knows what is right, but she also knows what is survivable for the school.

By Prize Day, her suspicion about Haz and East lingers, but she chooses stability over war, showing how leadership sometimes means living with imperfect endings.

Charlotte “Charley” Hicks

Charley Hicks arrives as an outsider literally inserted into the vacancy left by tragedy, and she carries that symbolic weight even before she understands it. She is academically gifted, bookish, and intensely self-contained, using reading and routine as armor against social performance.

Her old-fashioned clothes and plant-filled room underline her difference: she is not trying to win status, she is trying to survive herself. Charley’s home life, hinted at through her hostile goodbye with Fran and her vague references to “problems,” gives her a quiet hardness; she believes distance is freedom, and at first she treats Tiffin as a place to disappear into study rather than belong.

East disrupts that plan. With him, Charley feels seen as unusual in a way that becomes exciting, and her willingness to help build Priorities shows her craving for agency and partnership, not just romance.

Yet her arc is also about disillusionment. When she learns East slept with Simone, her sense of being chosen collapses into feeling used, and the emotional fallout is severe because she had risked trust.

Davi’s support helps Charley re-enter community on her own terms, and the final scene where she makes room for East suggests not a fairy-tale reunion but a more mature, guarded openness to forgiveness without forgetting.

Davi Banerjee

Davi Banerjee is the reigning social force of the fifth form, a girl who understands power as visibility and control. Cinnamon’s death is the crack in her armor: she carries guilt, grief, and a sense of unfinished loyalty that she cannot publicly collapse under, so instead she performs dominance even more intensely.

Her effort to bring Charley to First Dance shows her complexity; she can be both queen bee and caretaker, and Cinnamon’s memory pushes her toward the latter. Davi’s sharpness masks vulnerability, especially around her eating patterns and vomiting episodes, which read as a private battleground for control in a life where emotional chaos is rising.

She also lives in a shifting family landscape, and the revelation of her mother’s absence at Thanksgiving destabilizes her sense of home, reinforcing her need to anchor herself in school hierarchy. Davi initially mistrusts Charley as a threat or pawn in East’s orbit, but gradually she recognizes Charley’s integrity and starts to rely on her.

By the time Priorities collapses, Davi has become Charley’s protector and friend, suggesting that grief has widened her instead of simply hardening her. Her final silent encouragement to Charley to reconcile with East is Davi at her most evolved: still powerful, but now using that power to heal rather than to rule.

Andrew “East” Eastman

Andrew “East” Eastman is charisma wrapped around volatility. He moves through Tiffin with the entitlement of someone who knows the rules bend for him, yet his rebellion is not empty; it is fueled by boredom, intelligence, and resentment at being managed by structures he doesn’t respect.

East’s refusal to try academically is partly arrogance and partly self-protection, since he has already cycled through two schools and wants a future outside the expected elite pipeline. Priorities is his masterpiece of control: he creates a world beneath the school where he becomes architect, host, and king, turning secrecy into loyalty and glamour into leverage.

His relationship with Charley is the most revealing window into him. He genuinely likes her independence and mind, but he also uses her as a co-conspirator who validates his myth of originality.

The fact that he sleeps with Simone destroys whatever moral high ground he might claim; it demonstrates his capacity to treat boundaries as games and people as experiments. When exposed, East is both cornered and protected, and his survival without major punishment reinforces the theme of privilege as insulation.

Still, his repeated attempts to apologize to Charley and his tentative return to the group suggest that he is not purely villainous; he is a boy shaped by power he hasn’t learned to carry responsibly.

Webber “Dub” Austin

Dub Austin is the school’s golden boy quarterback, but The Academy frames him less as a jock archetype and more as a grieving teenager whose identity has been shattered. Cinnamon was not only his girlfriend but also the emotional compass that made his achievements feel meaningful.

After her death, he becomes loyal to her memory in a way that is both tender and paralyzing; he refuses to date, clings to the photo of them, and treats the unopened graduation-day email like a sacred relic. Football offers him a stage to be heroic, and the century-breaking win gives the school a burst of collective hope, yet Dub’s internal world remains heavy.

His friendship with Hakeem is tested by jealousy, betrayal, and the Zip Zap humiliation, and Dub’s discomfort with Taylor’s pursuit shows his emotional honesty: he cannot use someone else to patch his grief. His reaching out to Audre to shut down Zip Zap highlights his decency and fatigue with cruelty.

Dub’s arc is quieter than Charley’s or Davi’s, but it represents a different kind of survival: continuing to function while refusing to betray love.

Cinnamon Peters

Cinnamon Peters is physically absent yet narratively everywhere, the ghost that animates the year. Her suicide in Room 111 becomes a symbol of both fragility and failure, and every major character measures themselves against the vacuum she left.

To Dub, she is idealized love; to Davi, she is a lost sister and unhealed guilt; to Audre and Cordelia, she is a professional wound that questions their stewardship. Cinnamon’s role in the story is less about who she was in full detail and more about what her absence does: she turns celebration into something haunted, she makes surveillance feel urgent, and she forces everyone to confront how much of school life is performance masking pain.

Even the fact that Charley is admitted because of Cinnamon underscores the unsettling way tragedy becomes institutional logistics.

Rhode Rivera

Rhode Rivera is a young teacher and former Tiffin student who arrives hoping to modernize the school’s literature culture, only to be immediately constrained by tradition and board pressure. His frustration with being forced to keep classic texts reflects a larger theme of the academy as a place that markets progress but clings to old power.

Rhode is earnest, idealistic, and professionally hungry to matter, which makes his connection with Charley feel almost redemptive: she validates his love of books and reminds him why he wanted to teach. His relationship with Simone exposes his emotional naivety.

He is intoxicated by her attention, spends money he doesn’t have to impress her, and ends up humiliated, not because he is malicious but because he is trying too hard to be desired. Rhode also hovers near the edges of the Haz liquor plot, and his “business proposition” remark hints at moral grayness or at least opportunistic survival in a sharp environment.

He isn’t a moral anchor like Audre, but he is a portrait of a young adult still learning how easy it is to be pulled off balance by longing.

Simone Bergeron

Simone Bergeron embodies the danger of unresolved insecurity meeting institutional power. As a new teacher and dorm parent, she starts out anxious, craving authority she doesn’t yet feel, and shaken by the shadow of Cinnamon’s death.

East targets that weakness, and when he seduces her, the scene is framed as exploitation as much as consent, especially given her drinking and isolation. Simone’s guilt curdles into bitterness, and she spirals through heavy alcohol use, paranoia about Zip Zap exposure, and impulsive decisions.

Her attempt to expose Priorities is not pure heroism; it is fueled by jealousy, fear, and a desire to regain control after being used. The recording that destroys her is a cruel reversal: she tries to be whistleblower and becomes proof of scandal instead.

Simone is tragic rather than monstrous. She is responsible for her misconduct, but the narrative shows how quickly someone who is lonely, young, and out of place can collapse in a culture that rewards secrecy and punishes weakness.

Jesse “Big East” Eastman

Jesse Eastman, known as “Big East,” is an off-stage power broker whose influence shapes the entire ecosystem. His donation transformed Tiffin’s facilities and ambitions, and Audre’s constant anxiety about his expectations shows how donor money rewrites moral priorities.

He uses his son’s enrollment as leverage, whether or not he admits it, making East effectively untouchable. Big East represents the modern elite patron: outwardly beneficent, inwardly controlling, and able to warp consequences through wealth.

Karen Austin

Karen Austin appears briefly, but her presence underlines Dub’s emotional context. She arrives with him on Move-In Day, and the framed photo of Dub and Cinnamon among his things suggests not only Dub’s grief but also a family that supports his mourning rather than rushing him past it.

Karen functions as quiet stability in Dub’s storm.

Cordelia Spooner

Cordelia Spooner, the admissions director, is both institutional mind and grieving heart. Cinnamon had been her star tour guide and living proof of Tiffin’s appeal, so Cordelia’s sorrow is personal and professional.

She is excited by the flood of new applicants after the #2 ranking, yet the joy is complicated by her awareness of how fragile prestige is and how easily tragedy can be commodified as renewal. Her secret relationship with Honey adds another layer: Cordelia wants love but also fears vulnerability in a workplace where reputation is currency.

When Honey resigns, Cordelia is devastated not only by heartbreak but by the public erasure of something she had cherished in private, leaving her to keep performing competence while hollowed out.

Honey Vandermeid

Honey Vandermeid, the college counselor, is overwhelmed, emotionally distant, and caught between private desire and public restraint. Her summer relationship with Cordelia deteriorates under pressure and unspoken fear, suggesting that she retreats when intimacy threatens to become real inside the academy’s spotlight.

Simone’s accusation that Honey made an unwanted advance complicates her further. Honey admits it and resigns immediately, which implies remorse and self-awareness rather than denial.

She becomes a reminder that adults at Tiffin also falter, and the institution’s glossy surface contains as much mess among staff as among students.

Chef Haz Flanders

Chef Haz Flanders is a lovable, risky wildcard in the adult cast. On the surface he is the warmhearted provider whose upgraded cookout and hangover breakfasts function like comfort rituals for students.

Beneath that, he is burdened by gambling debts and a past scandal that Big East helped bury, leaving him beholden and vulnerable. His secret liquor-buying spree places him at the core of Priorities’ supply chain, and his discretion at the Alibi bar shows his instinct for survival through silence.

Haz occupies a morally ambiguous space: he cares about the kids’ happiness and wants to belong at Tiffin, but he also enables dangerous behavior to solve his own problems. Audre’s final suspicion about him hangs unresolved, emphasizing how some compromises are quietly absorbed into the academy’s foundations.

Hakeem Pryce

Hakeem Pryce is Dub’s best friend and a high-status athlete whose confidence masks insecurity. His resentment about being a virgin, pressure on Taylor, and eventual cheating show his anxiety about masculinity and image.

With recruiting attention rising, he becomes more reckless, and his affair with Taylor in the shadow of Priorities suggests he wants both emotional reassurance and conquest. Hakeem’s jealousy toward Dub’s bond with Taylor fuels their friendship’s fracture, and his poor performance after the Zip Zap drama illustrates how reputation games can unmake even the most talented students.

Taylor Wilson

Taylor Wilson is caught between desire, loyalty, and her own pace of readiness. She likes Dub and reaches for him partly because she wants to feel chosen, but she also remains emotionally tethered to Hakeem despite his betrayal.

Her wish to lose her virginity to Dub reads less as lust and more as a longing for safety and certainty, and the public Zip Zap exposure of that private desire is a violation that forces her into the brutal theatre of school gossip. Her eventual affair with Hakeem suggests she is drawn back into the familiar gravity of their chemistry, even as she hesitates physically, showing her internal conflict between agency and attachment.

Olivia H-T

Olivia H-T functions as the story’s excluded observer turned catalyst. She notices the fifth-formers’ secrecy, feels the sting of being outside the inner circle, and channels that hurt into investigation.

Olivia is not purely altruistic; her decision to report suspicions to Simone is as much about reclaiming importance as about safety. Still, her instincts are sharp, and she becomes the fuse that detonates Priorities.

Her Thanksgiving scenes also reveal quiet deprivation in her home life, helping explain why social belonging at school matters so intensely to her.

Beatrix

Beatrix is Charley’s best friend from Towson and the tether to Charley’s former identity. Through texts, Beatrix becomes Charley’s confessional space, the person to whom Charley can admit loneliness without losing face at Tiffin.

Even off-campus, she represents what Charley is running from and what she might still need.

Fran Hicks

Fran Hicks, Charley’s mother, appears mainly through the Move-In conflict, but that scene is loaded. Fran’s open regret about sending Charley away and Charley’s fury suggest a home dynamic of pressure, misunderstanding, or emotional damage.

Fran is the embodiment of the “problems at home” Charley refuses to detail, and the hostile goodbye makes clear that Charley’s independence is partly a wound response.

Madison J.

Madison J. is a first-floor prefect who acts as a gatekeeper figure.

Her calm authority when Charley returns late, and her alignment with the Priorities group, show her as someone who thrives within systems of rule-enforcement and rule-breaking alike. She is pragmatic, socially protected, and comfortable in the gray zones that weaker students fear.

Ravenna Rapsicoli

Ravenna Rapsicoli, editor of the student newspaper, is a minor but telling presence. By recruiting Charley for a gossip-style feature on Davi, Ravenna embodies the academy’s appetite for curated narratives and subtle cruelty.

She gives Charley a foothold in community, but it is a foothold built on observing and packaging others, reflecting how students learn the institution’s values through media and status games.

Reed Wheeler

Reed Wheeler is a younger student who overhears Rhode’s comment to Haz, functioning as a reminder that in a surveillance culture, even offhand adult whispers can become student weaponry. He represents the constant risk of rumor ignition.

Mr. James

Mr. James, the custodian, appears briefly during Simone’s panic search.

His minimization of her worry underscores a theme of institutional fatigue: adults accustomed to the machine sometimes dismiss the alarms of newer staff, enabling danger through inertia.

Roy Ewanick

Roy Ewanick acts as the procedural enforcer who calls Audre in and plays East’s recording. He is the academy’s accountability mechanism, but also a symbol of how evidence and power determine outcomes more than moral nuance.

His presence reinforces that institutions punish what they can prove, not always what is most harmful.

Mikayla

Mikayla, head of Old Bennington, enters as external scrutiny. Her involvement in examining Tiffin’s ranking jump embodies the wider world’s suspicion of elite success, and her warning to Audre about Zip Zap shows that reputational threats now travel beyond campus walls.

Cassie Lee

Cassie Lee is a younger student pulled into Hakeem’s orbit after his fallout with Taylor and Dub. Their brief attachment, and her eventual breakup due to his secrecy, highlight how older students’ hidden worlds damage those who get close without access to the rules.

Willow

Willow is one of the Priorities invitees and part of the fifth-form inner ring. Though lightly sketched, she stands for the kind of student who values belonging to exclusivity more than questioning its ethics, reinforcing East’s ability to build loyalty through glamour.

Royce

Royce, another invitee, similarly functions as part of the protected elite cluster. His inclusion underscores how Priorities is not just rebellion but a social sorting mechanism: the chosen few rehearsing adulthood in secret.

Ruby Banerjee

Ruby Banerjee, Davi’s mother, is mostly seen through absence and discovery. Davi’s shock at finding Ruby in Kentucky during Thanksgiving reveals a fracture in parental reliability, and Ruby becomes a quiet source of Davi’s destabilization, helping explain Davi’s compulsions around control and performance.

Themes

Grief, memory, and the aftershock of loss

From the first moments on campus, the school is functioning inside a shadow that will not lift just because a new term begins. Cinnamon’s death is not treated as a closed event but as a continuing pressure system shaping how people move, what they notice, and what they refuse to say.

Audre tries to project steadiness, yet the simple act of walking students into room 111 South forces her to confront how institutions ask individuals to domesticate trauma for the sake of routine. The fifth-formers, especially those closest to Cinnamon, carry grief in different postures: Dub clings to loyalty and a version of love that feels frozen in time, while Davi performs control and charisma to keep panic at bay.

Their grief is not only emotional but social; on a campus where status is currency, the person who died becomes a reference point for who mattered, who was trusted, who is allowed to hurt, and who must “be okay” for everyone else. The ranking announcement adds a strange whiplash—public triumph landing directly on private sorrow.

Celebration becomes both relief and avoidance, an opportunity to declare the school “back” without sitting with why it fell apart. That tension makes grief feel communal but also competitive: some students get to mourn loudly, others are expected to move on, and new people like Charley are forced to inhabit a tragedy they didn’t witness.

Her move into Cinnamon’s room turns grief into architecture; the room is a physical reminder that the past occupies space whether or not you consent. The story keeps showing that bereavement is never neutral at Tiffin.

It is watched, interpreted, and used—sometimes for comfort, sometimes for leverage. What emerges is grief as a long-term climate rather than a scene, shaping friendships, romances, faculty decisions, and even the school’s self-image, which tries to replace mourning with prestige but can’t fully succeed.

Power, privilege, and institutional self-preservation

Tiffin’s glossy success depends on a hierarchy that everyone understands even when they pretend not to. The school’s sudden climb to #2 is framed as a triumph, but it also functions as a shield—proof of excellence that can be held up whenever discomfort appears.

Audre’s reactions show the moral cost of running a place where reputation and donor dependence are intertwined. She knows that East’s father effectively keeps the lights on, so East’s rule-breaking is tolerated in advance, before any actual crisis happens.

That permissiveness isn’t abstract; it shapes everyday authority. Students see which rules are flexible for the powerful and which are rigid for everyone else, and they internalize that lesson as normal.

East’s ability to commandeer tunnels, access renovation blueprints, and manipulate adults comes directly from this ecosystem. Even when his actions spiral into a secret bar beneath the dorms, the eventual response is not a clean moral reckoning but a calculation about stability.

The school protects itself by narrowing the definition of the problem: the staff member who can be fired is removed swiftly, while the student whose family controls resources remains mostly insulated. This is not presented as a shocking twist; it’s shown as the ordinary gravity of elite spaces, where “good for the school” can quietly override “right for the people.

” The teachers are caught in the same web. Rhode’s curriculum is policed by a board that treats tradition as branding, and Simone’s vulnerability as a new teacher turns into a disaster that the institution manages by sacrificing her and smoothing the narrative.

Even the speakeasy, Priorities, is a metaphor for privilege: a luxury world hidden below the official one, open only to a curated circle, sustained by money, secrecy, and the assumption that consequences can be negotiated. The ending reinforces how power reproduces itself.

Audre suspects Haz’s role in supplying liquor but chooses not to look further, not because she doesn’t know, but because knowing would demand action that threatens the school’s delicate arrangement. The theme isn’t that people are evil; it’s that the institution rewards silence, and privilege teaches its holders that the system will bend to keep them safe.

Belonging, status performance, and the fear of exclusion

Social life at Tiffin is built around a constant audition. Students are rarely just friends; they are positions in a shifting map of visibility.

Davi embodies this world most clearly. Her dominance isn’t only personality—it’s labor.

She maintains an image for others to orbit, and that image becomes a survival strategy after Cinnamon’s death. Losing her best friend threatens her centrality, so she doubles down on control: clothes become uniforms, events become stages, and kindness is sometimes sincere and sometimes tactical.

Charley enters as a disruption to that choreography. She is neither fluent in Tiffin’s signals nor eager to learn them, and her refusal to chase approval exposes how much energy everyone else spends chasing it.

Yet even Charley’s independence is complicated. Her isolation looks like defiance, but it also reads as self-protection from another kind of exclusion—whatever pushed her out of her previous life.

Because she doesn’t perform the expected version of “new girl,” people project onto her: Davi imagines a rival, East imagines a partner in rebellion, teachers imagine a promising student who might validate their own hopes about teaching. Belonging becomes a series of negotiations about who gets to define someone else.

The speakeasy intensifies this theme by turning inclusion into a secret membership. Priorities feels intoxicating not only because of alcohol but because it offers a shortcut to certainty: you are either chosen or not.

Olivia’s growing suspicion dramatizes the pain of being outside a circle you thought you had earned. The group’s weekly ritual also shows how status can become emotional dependency; secrecy gives them a shared identity when the daytime school world feels unstable.

The heartbreaks in the story—Davi learning East has chosen Charley for Kringle, Dub confronting the inevitability of Taylor and Hakeem, Charley realizing East’s double life—are all tied to belonging: who is wanted, who is replaceable, who gets to be at the center. By the end, the tentative reconciliation among the Priorities group doesn’t erase the status system, but it suggests that real connection can occur when people stop treating one another as roles to be managed and start acknowledging the loneliness underneath their performances.

Secrecy, rule-breaking, and the thrill of private worlds

Almost everyone in The Academy lives inside at least one secret, and those secrets act like alternative currencies. Some are intimate, like Dub’s unopened email from Cinnamon, and some are structural, like the school’s willingness to ignore East’s transgressions.

The story treats secrecy not as a rare act but as a core adolescent method for testing reality. The tunnel becomes the literal pathway for this theme: a hidden route that allows students to step outside surveillance, invent new rituals, and temporarily outrun grief, expectations, and boredom.

For Charley, secrecy starts as escape and becomes belonging; sneaking out to meet East offers her a life where her choices feel self-authored. For East, secrets are a performance of power—proof that he can create a world under the world.

Priorities is the most developed expression of this impulse. It is carefully curated, formal, and exclusive, almost like a parody of the adult privilege that surrounds them.

The students’ careful self-regulation—drinking but not too much, keeping the circle tight, returning home without evidence—shows how secrecy can develop its own ethics. They believe this private world is safer than the official one because they control it.

But the novel keeps showing the instability of secrets. They depend on trust, and trust is fragile in a community where status matters.

Olivia’s discovery and Simone’s drunken confrontation demonstrate that a secret’s collapse is often less about the act itself than about who feels excluded. When the hidden bar is exposed, the fallout reveals another layer: secrecy protects some people while destroying others.

East uses a recording to shield himself and incriminate Simone; Audre uses administrative framing to absorb the speakeasy into school ownership; Haz’s role is suspected but deliberately left unspoken. The theme lands on a sobering idea: rule-breaking can feel like freedom, but in unequal systems, the freedom is distributed unevenly.

Some can treat secrets as games; others become casualties when the game ends. The tunnel doesn’t just hide misbehavior—it exposes how control, fear, and desire shape what people choose to keep private.

Desire, consent, and the moral confusion of adolescence and adulthood

Romantic and sexual desire in the book is rarely simple attraction; it’s entangled with grief, insecurity, and power. The students are learning not only what they want but what wanting means in a culture that constantly watches and judges them.

Dub’s loyalty to Cinnamon shows desire as remembrance, refusing to convert love into a new relationship because doing so would feel like betrayal. Taylor’s wish to be with Dub, and Hakeem’s simultaneous pressure and infidelity, show desire as status anxiety—sex becomes a marker of maturity in their peer world, not just intimacy.

Davi’s complicated pull toward East reflects a different layer: she wants to be chosen in a way that would reaffirm her social standing and soothe the wound Cinnamon’s death left behind. Charley and East’s relationship, meanwhile, begins as a mutual fascination with rule-breaking and difference.

Their flirtation is playful and real, but it also sits on a subtle imbalance. East is practiced at manipulation, confident in his invulnerability, and Charley is new enough to read his attention as exceptional.

When she later learns about his involvement with Simone, her feeling of being used isn’t just jealousy; it’s a sudden recognition that she may have been a character in someone else’s script. The most disturbing thread is Simone’s sexual encounter with East.

The novel doesn’t excuse it through romance or confusion. It shows how adult loneliness, alcohol, and insecurity can slide into catastrophic boundary failure, and how a student with privilege can weaponize that event afterward.

Consent here is not treated as a checklist but as a terrain shaped by context: authority, age, fear, and the need to feel wanted. The aftermath deepens the theme because the institution responds in ways that blur morality.

Simone is fired and disgraced; East’s role is minimized; Honey’s admission of an unwanted advance leads to resignation. These parallel collapses show that desire without clear boundaries can corrode trust at every level—student to student, teacher to student, colleague to colleague.

The final fragile reconciliation between East and Charley doesn’t sanitize what happened. It suggests that young people can move toward forgiveness while still carrying the bruises of betrayal.

Overall, desire in The Academy is shown as both a force of connection and a site of risk, especially in environments where power differences make it easy for attraction to become harm.