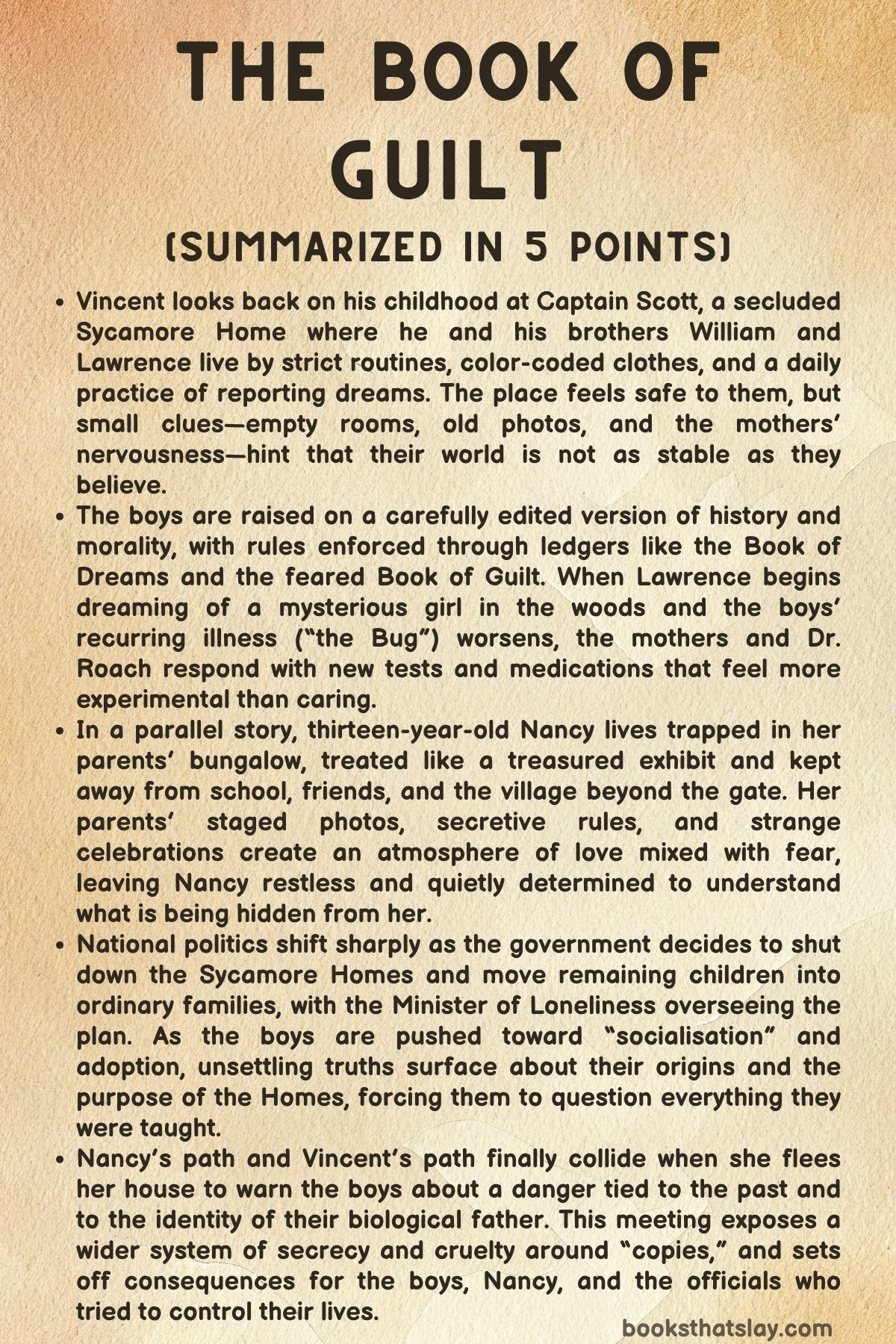

The Book of Guilt Summary, Characters and Themes

The Book of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey is a quiet, unsettling alternate-history novel set in late-1970s England. It follows Vincent, one of three identical boys raised in a secluded Sycamore Home called Captain Scott, and Nancy, a sheltered girl growing up under strict, strange parents.

The country around them is changing: a new government is closing the Homes, drug experiments lie behind the boys’ illnesses, and the public fears what the children really are. Through Vincent’s careful, child-shaped memory and Nancy’s hungry curiosity about the world, the book examines identity, state control, family love turned cruel, and the long afterlife of secrets.

Summary

Vincent grows up inside Captain Scott, a grand, worn house hidden behind high flint walls near Ashbridge village. He lives with his brothers, William and Lawrence, the last boys left in a network of Sycamore Homes.

Their days are shaped by rules and repetition. Three women — Mother Morning, Mother Afternoon, and Mother Night — care for them in shifts, and the boys accept them as family.

The house feels safe because it is bounded and predictable: dreams are recorded each morning in a Book of Dreams, manners are drilled, clothes are color-coded, and misbehavior is threatened with entry in the Book of Guilt. In the garden, the triplets invent games and rituals, offering little treasures to imagined “garden gods,” and explore empty rooms left behind by boys who have already gone to Margate, a seaside place promised in cheerful brochures.

The boys are taught a revised national story from the Book of Knowledge, including a version of World War II in which Hitler was assassinated and a treaty ended the war early. The lesson is clear: the state sometimes makes hard choices for the greater good.

Vincent learns to repeat this idea even when he does not understand it. The brothers also play their own secret games, like swapping shirts to trade identities for a day, testing how easily adults can be fooled.

Captain Scott has rules about the outside world. For years the boys are told they are too delicate to visit the village, but in 1978 they are allowed to go with a Mother if they feel well.

Their first trips are thrilling, yet villagers stare and whisper. Vincent hears comments that he is a “pitiful creature” who has never known real love.

The Mothers dismiss this, insisting the boys are cherished, but the unease lingers. Vincent begins noticing that the Home is shrinking, with no new arrivals and government funding fading.

A recurring illness known as the Bug keeps the boys weak: rashes, joint pain, nausea, heart trouble, and sometimes death. Treatments are constant — drips, injections, pills — and the boys accept pain as normal.

Those who recover are sent to Margate, described as sunny and full of amusements. The triplets long for their own brochure but remain behind.

Slowly, Captain Scott becomes a place of echoes and leftover belongings.

Dr Roach, a polite, distant scientist, visits to monitor their health and dreams. He brings a fox terrier named Cynthia, identical to one he brought before; the old dog has died and been replaced without ceremony.

The incident exposes a quiet cruelty in the adults’ world, where substitutions are made to keep everything looking the same. William, already sharp-edged, harms the dog and bullies Vincent into swallowing a cockroach.

Vincent says nothing, torn between fear and loyalty.

As 1979 advances, the Bug worsens. Lawrence reports a dream of chasing a skinny barefoot girl through woods; Mother Morning presses him hard for details.

Soon Vincent begins dreaming of the same girl, always running just ahead, always unreachable. Lawrence’s joints ache, William breaks out in hives, and Vincent’s heart flutters in the night.

Dr Roach switches their medication to a new set of pills. Vincent cannot sleep and seeks comfort from Mother Night, who tells him about ordinary childhoods outside the Home.

Her stories awaken both hope and dread in him.

Parallel to this, Nancy turns thirteen in a bungalow far away. Her parents pierce her ears at the kitchen table, photograph her carefully, and keep her inside their gated world.

Nancy longs for school and friends, but her parents insist the outside is dangerous. Her father builds an elaborate model village in the sitting room, decorating it as if for a celebration that never quite arrives.

Nancy dreams of shrinking into the model village, where a whispering girl urges her to stay. Each dream ends with a cuckoo clock forcing her out.

National politics shift sharply. A Conservative government comes to power and announces the end of the Sycamore Scheme.

Sylvia Dalton, the Minister of Loneliness, is tasked with closing the Homes and rehoming the remaining children with approved families. She visits Captain Scott and tells the Mothers and boys that Socialisation Days with girls from another Home will prepare them for life beyond the walls.

The Mothers are devastated; Dr Roach warns of sickness and contamination. The boys are stunned, thrilled, and terrified all at once.

Sylvia’s role deepens in a darker direction when she visits Strangeways prison. Arthur Powell, a serial killer newly returned to the death penalty list, asks to see her.

She recognizes him as the biological father of the triplets. Powell claims he knows where one missing victim, Nancy Liddell, is buried and offers to reveal the location only if Sylvia brings him his sons.

Sylvia agrees, partly driven by conscience and partly by political need.

She takes the boys to Strangeways, telling them their father is alive and wishes to meet them. The triplets are excited, imagining a loving parent.

In the prison visiting room, they face Powell through glass and are shocked by their resemblance. Powell speaks smoothly about manners and “protecting young ladies,” and listens closely when they mention dreams of a girl in the woods.

The next morning he is hanged. Sylvia is left with guilt and no burial revelation.

Back in Nancy’s house, a strange “party” takes place: lavish cake, decorations, three-person toast to being “free,” then collapse into despair. Two nights later, Nancy sees a television appeal featuring the Sycamore triplets.

Her parents react with horror and familiarity. Nancy realizes the boys are connected to a secret they have hidden from her.

When she overhears her parents preparing to sedate William — taken into their home as part of the rehoming plan — she understands they plan to kill him in revenge for their murdered daughter. She escapes and hitchhikes toward Ashbridge.

On the road, Nancy is both naive and brave, frightened by traffic, charmed and confused by small kindnesses, and unsettled by a driver who thinks she resembles the dead Nancy Liddell. Reaching Ashbridge, she is thrown off by village clocks showing different times and by ponies wandering freely.

She follows directions to Captain Scott, climbs the glass-topped wall using a pony’s back to gain height, and cuts herself getting over. Inside the grounds she meets Vincent, and both are shaken: she looks exactly like the girl from his dreams.

Nancy tells Vincent that her parents are really Keith and Mary Liddell, living under false names, and that William is in danger. She shows him a newspaper cutting on Powell’s crimes.

Vincent pieces together the truth: the triplets are copies made from Powell’s genetics, and Nancy is a copy of Nancy Liddell. He tries to find Mother Morning, only to discover her drunk and helpless.

With Nancy, he forces open the North Wing and calls Sylvia Dalton, begging for help without police. Sylvia understands the full picture and sends officers anyway.

The police arrive at the Liddells’ house in time to stop the murder, but not before William is mutilated, including losing his tongue. The public scandal ruins Sylvia’s career.

The Prime Minister abandons the rehoming plan and reframes the story to protect the state. Sylvia resigns and becomes an activist for copies’ legal rights.

Captain Scott is repopulated with children from other closed Homes, and a new carer replaces Mother Morning. William returns silent and damaged, refusing Vincent’s attempts at closeness.

Lawrence runs away and disappears. Years later, Vincent becomes a librarian.

Nancy builds a life with him, neither fully free of what made them. They know many children “sent to Margate” never lived there at all.

In old age, Vincent and Nancy visit Margate for an exhibition about the Sycamore Scheme. The promised attractions are gone, and the museum reveals the system’s real purpose: copies bred for drug trials and disposed of when inconvenient.

Vincent finds the Book of Guilt and reads a final entry that links an old girl’s death to his own childhood actions. Overcome, he collapses and is helped by an elderly volunteer who turns out to be Mother Night.

She is regretful, still carrying what she did and did not do. Together, she, Vincent, and Nancy walk by the sea, living with the past that cannot be corrected, only faced.

Characters

Vincent

Vincent is the novel’s first-person lens and emotional barometer, a boy raised inside Captain Scott who grows into an adult still trying to assemble the truth of what was done to him. As a child he is curious, observant, and quietly imaginative, turning the garden into a sacred playground of “offerings” and gods, which signals both his need for meaning and the thinness of the world he’s been given.

He craves order because order is survival at the Home—neat clothes, correct manners, present-tense dream reports—yet he also has a sly, restless inner life that slips out in mockery, small rebellions, and private carving. What defines Vincent most is his moral sensitivity: he sees William’s cruelties clearly, feels guilt over his own compliance, and carries protective love for Lawrence even when fear makes him hesitate.

His insomnia and fluttering heart parallel his growing awareness that something is wrong with their lives; sleeplessness becomes both symptom and metaphor for a mind that can’t stay sedated by the official story. As an adult, Vincent is still shaped by the Home’s logic of surveillance and blame—he measures himself against the unseen Book of Guilt even when the institution is gone.

His later life as a librarian fits his core impulse: to record, preserve, and understand. Yet knowledge does not free him instantly; the Margate exhibition and the discovery of the final entry about Jane collapse the distance he tried to keep from the past.

Vincent embodies the long afterlife of institutional harm: he survives, loves, makes a life with Nancy, but remains haunted by the boys erased under the euphemism of “sent to Margate,” and by his own complicity as a child who learned obedience before he learned choice.

William

William is Vincent’s brother and foil, the triplet who most aggressively metabolizes the Home’s lessons into domination. As a child he is charismatic, sharp, and performatively confident, thriving on the identity-swapping game and on pushing boundaries the mothers fail to notice.

But beneath the surface play is a streak of cruelty that seems both innate and cultivated by the Home’s moral vacuum: stamping on Cynthia’s paw, coercing Vincent into swallowing a cockroach, and repeatedly weaponizing fear and shame. William’s behavior reads like a desperate assertion of agency in a system that denies real autonomy; if the Home treats them as experiments, he will become the experimenter.

He is also intensely guarded; his refusal to share his dreams suggests a private terror he cannot risk exposing to the mothers’ notebooks or to his brothers. When he learns they are “copies,” William’s contempt hardens into defiance, and he becomes the most openly rebellious once medication stops—smearing paint, destroying their craft, mocking dream rituals—because he recognizes, earlier than the others, that the ritual is a leash.

His later mutilation at the hands of Nancy’s parents is a brutal culmination of the social violence directed at copies: he is punished not for who he is but for what he represents. The loss of his tongue is symbolically exact—William, once the loudest voice, is silenced by a world that never wanted to hear him as human.

Afterward he withdraws into trauma and refusal, a living reminder that survival can also mean a life contracted by pain. William remains one of the book’s darkest questions: whether cruelty is a personal failing, a defense against captivity, or the inevitable product of being raised inside a system that trains children to view bodies as objects.

Lawrence

Lawrence is the gentlest of the triplets, marked by physical fragility and emotional openness that make him both sympathetic and vulnerable. He is the first to dream of the barefoot girl in the woods, and his dream functions like a crack in the Home’s sealed reality; the fact that Mother Morning reacts sharply to it suggests Lawrence is unknowingly brushing against the truth.

Unlike William, Lawrence does not weaponize his powerlessness. He is earnest, eager to do right, and deeply attached to the Home’s patterned safety even as his body rebels through joint pain and Bug episodes.

Lawrence’s anger at William’s cruelty toward Cynthia shows a strong moral instinct, but his instinct is paired with fear; he wants to report wrongdoing, yet he also depends on the fragile peace of brotherhood. His dreams are calmer and more tender than Vincent’s, implying a personality that seeks pleasure and reassurance rather than mastery.

When Nancy arrives, Lawrence panics and flees, which is less cowardice than a child’s overwhelmed response to the sudden collapse of the world-story he relied on. His later disappearance after running away captures the fate of many institutional survivors: some can’t stay within the new order, and some aren’t equipped to navigate it.

Lawrence becomes a kind of absence-character, haunting Vincent’s adulthood as the brother who slipped out of reach, representing both the costs of the Scheme and the unrecorded lives that vanish between official narratives.

Nancy (the living Nancy / “copy” of Nancy Liddell)

Nancy is raised in a private prison disguised as a family home, and her character is defined by the tension between intense innocence and startling courage. As a child she is obedient on the surface, posed and photographed like an artifact, yet inwardly she is hungry for experience: school, friends, the world beyond the gate.

Her parents’ fear leaks into her life as an undefined dread, making her perceptive about emotion even when she lacks information. The model village sequence reveals how Nancy’s imagination becomes her survival; she dreams of entry into a miniature world where she is welcomed, but always forced to leave, echoing her own exclusion from real society.

When she finally flees to Ashbridge, her bravery is raw and untrained—she doesn’t understand seatbelts or candy, and still she chooses motion over safety because she believes a boy’s life depends on her. That leap into the world makes her both vulnerable to predatory adult attention and fiercely self-directing; she endures Ant’s creepiness and still keeps going.

Nancy’s shock-recognition of Vincent as the dream-boy ties her to the novel’s larger metaphysics of memory and copying, but her humanity is never reducible to being a replica. She is the most morally lucid character in the crisis, correctly naming the danger her parents represent and refusing to involve police to protect them from execution, which shows both deep love and the warped ethics bred by fear.

As an adult living with Vincent, Nancy represents the possibility of tenderness after trauma—someone who tries to build normality without denying the past. Yet she, too, is haunted: by the dead girl she was patterned after, by the parents who loved her as replacement and nearly became killers, and by the knowledge that her own existence was engineered as a political and scientific convenience.

Nancy’s arc insists that identity is not origin; she is not a ghost of Nancy Liddell but a person who grows into her own life while carrying an impossible inheritance.

Sylvia Dalton (Minister of Loneliness)

Sylvia Dalton begins as a polished political operator who speaks the language of efficiency and “greater good,” yet her character steadily complicates into one of the book’s central moral battlegrounds. In public she defends closing the Sycamore Homes as financial pragmatism and social policy, projecting calm authority even when challenged about deaths and disturbances.

Privately she is uneasy, which signals a conscience still active beneath her party role. Her confrontation with Arthur Powell detonates her political identity: faced with a man who is both monster and biological father to the triplets, she is pulled into a bargain that mixes ambition, guilt, and desperate hope for closure in the Nancy Liddell case.

Sylvia’s decision to bring the boys to Strangeways is ethically disastrous, but psychologically coherent; she is trapped in a system where children are already instruments, and she tries to use the same logic for a political win. The pivotal shift comes after William’s near-murder and mutilation: Sylvia recognizes the boys and Nancy not as policy units but as people whose suffering reflects the state’s crimes.

Her career’s collapse is a narrative judgment, yet the novel also grants her the possibility of redemption through activism. She becomes a public defender of copies’ rights, enduring ridicule and attack, which reveals a stubborn moral courage she hadn’t fully claimed before.

Sylvia is thus not a simple villain or savior; she is the face of state power learning, too late, what harm her own rhetoric enabled. Her arc exposes how bureaucratic cruelty is often carried out by people who can feel remorse, and how remorse only matters if it turns into responsibility.

Dr Roach

Dr Roach is the Scheme’s scientific conscience and its most chilling embodiment of paternalistic control. He presents himself as affable, kindly, and devoted—arriving in a Jaguar with a fox terrier, chatting over cakes with the mothers—yet his warmth masks a ruthless utilitarianism.

To Roach, the boys are “life’s work,” a phrase that sounds loving but also proprietary; their bodies are the laboratory through which he pursues progress. His casual replacement of the original Cynthia with an identical dog exposes his worldview: continuity is more important than individuality, and grief can be solved by substitution.

That logic is precisely what created the copies. Roach’s medical authority dominates Captain Scott’s rhythms, from injections to experimental pills that kill some boys, and he never frames those deaths as moral failure—only as data in an uncompleted trial.

His revised war history lessons reinforce the scientific-state ideology that justifies sacrifice for future benefit, suggesting Roach is both product and priest of that ideology. When funding ends, his panic about who will manage medication and about the Bug spreading shows not only concern but fear of losing control over an experiment he believes only he understands.

Roach is tragic in a narrow way, because he may genuinely believe he is helping humanity and protecting the boys, but the tragedy is inseparable from atrocity. He represents the terrifying calm of institutional science when detached from consent: a man whose devotion to “care” becomes indistinguishable from ownership.

Mother Morning

Mother Morning is the Home’s daylight authority and the clearest personification of ritual surveillance. She is brisk, competent, and deeply invested in the rules that structure the boys’ lives: waking, exercise, dream recitation, moral accounting, and daily medication.

Her recording of dreams in present tense is meant to keep the boys psychologically accessible and scientifically useful, but it also gives her an intimate power over their inner lives. Her unusually sharp reaction to Lawrence’s dream suggests either foreknowledge of its significance or a fear of what it might reveal; in either case, it shows her as gatekeeper of narrative truth.

Mother Morning’s threat to write Vincent in the Book of Guilt is a key tool of discipline, linking affection to conditional moral worth. Yet she is not purely a bureaucrat; she seems to love the boys in the only way the Scheme trained her to love—through caretaking fused with control.

When the rehoming decision arrives, her devastation hints at a life organized around these children, with no identity beyond the Home. Her eventual collapse into drunkenness when crisis peaks exposes the psychic cost of sustaining a system she can’t fully justify.

Mother Morning is a study in institutional motherhood: nurturing and coercive at once, capable of tenderness but unable to imagine care outside surveillance.

Mother Afternoon

Mother Afternoon is the Home’s soft middle light, more playful and pragmatic than Mother Morning. She manages daily life with warmth and teasing banter, especially in her conversations with Vincent about being loved and their shared newspaper-contest fantasy.

She is the mother who tries to translate hard realities into reassurance, often smoothing over villagers’ cruelty or the boys’ anxieties rather than confronting them directly. That instinct makes her emotionally safe for the children, but it also keeps them insulated from truth.

Her tour of the Home for the Minister is a performance of pride and defensiveness; she wants the institution seen as orderly and caring, because her identity is entwined with proving the Scheme humane. The moment Lawrence vomits during that tour breaks her carefully held front, showing how fragile her control really is.

Mother Afternoon embodies the everyday kindness that can exist inside a harmful system, and the way such kindness can become part of the harm by making captivity feel like home.

Mother Night

Mother Night is the most quietly radical presence at Captain Scott, a figure of genuine human contact within an engineered world. Her night-shift setting already marks her as liminal—she works when the Home is hushed and the boys’ defenses are down.

She listens rather than interrogates, knitting by the radio, offering Vincent not instruction but companionship. When she tells him about ordinary childhood games and family life, she gives him something the Scheme never intended: a sense that other worlds exist and that their world is not natural law.

Her support for rehoming reveals both hope and realism; she believes an ordinary life is better, even if it’s frightening, which makes her the only carer to articulate a future not defined by Captain Scott or Margate. In the closing decades-later encounter, she reappears as an elderly volunteer at Margate, carrying remorse and memory.

Her recognition of Vincent, and their walk by the sea afterward, positions her as a witness who did not fully resist but also did not fully surrender her conscience. Mother Night represents the possibility of care that is not ownership: imperfect, complicit by position, but still oriented toward the children’s personhood.

Diane

Diane appears briefly yet meaningfully as one of the Sycamore girls brought for Socialisation Days, and her presence signals the widening of the Scheme’s collapsing boundaries. She functions less as a fully developed individual in the summary and more as a mirror for the boys’ expectations of “girls” and “outside life.

” Her arrival, alongside Karen’s degraded state, punctures the boys’ romanticized fantasies about socialisation and reveals the human cost scattered across other Homes. Diane’s relative normality and youth show that not all copies are visibly broken, which intensifies the tragedy of what is being done to them.

Even in a small role, she helps shift Captain Scott from sealed sanctuary to porous site of reckoning.

Karen

Karen’s thin, shaken return is a haunting emblem of the Scheme’s violence. Vincent barely recognizes her, which implies a past connection—likely one of the girls previously socialised or a survivor from another Home now ruined by trials, neglect, or the Bug.

Her body tells a story the institution refuses to record honestly: that children have been chewed up by experimentation and isolation. Karen’s silence in the summary makes her a kind of living document of harm, forcing the boys—and the reader—to confront what “Margate” and Sycamore care really mean.

She is less a plot driver than a moral flare, collapsing any remaining ambiguity about the Scheme’s brutality.

Arthur Powell

Arthur Powell is the novel’s concentrated horror, a serial killer whose existence reveals the Scheme’s origins in moral rot. He is biologically the boys’ source, and his interest in meeting them is not paternal love but narcissistic possession and ideological grooming.

His prison interview drips with control; he tests their manners, frames women as prey needing male supervision, and responds avidly to their dreams of the woodland girl, implying a chilling relationship between their engineered psyches and his crimes. Powell’s bargain with Sylvia is classic predator logic: he offers closure on Nancy Liddell’s burial only by forcing access to fresh victims, using guilt and ambition as his bait.

His execution is treated publicly as spectacle, yet the novel doesn’t allow catharsis, because Powell’s legacy is already replicated in living bodies and in a state apparatus that found his DNA useful. He is both individual monster and proof that society’s line between punishment and exploitation is thin; the state kills him while building policy on his genetic material.

Keith and Mary Liddell (living as Mr and Mrs Fletcher)

Nancy’s parents are tragic antagonists, driven by grief that curdles into obsession and moral collapse. Their household is a theatre of denial: staged photographs, curated dresses, a model village that replaces the real world, and a “party” celebrating freedom that dissolves into despair.

They love Nancy, but their love is conditional on her being a substitute for the dead daughter they cannot relinquish; their tenderness is intertwined with control, confinement, and fear of outside contamination. The recognition of the triplets on television triggers a delusional logic of revenge, and they sedate William with the intent to kill him as if murdering a copy could undo their loss.

Their plan shows how state secrecy doesn’t just harm copies directly; it warps citizens into conspirators against humanity. When police find knives, rope, and plastic sheeting, the parents are exposed not as monsters by nature but as people whose grief was never allowed a truthful ending.

Even after their thwarted crime, the Prime Minister’s spin reframes them as sympathetic mourners, highlighting how easily society excuses violence against copies. Keith and Mary are a portrait of bereavement turned corrosive by a culture that offers replacement instead of mourning, and that teaches people to dehumanize the replaced.

Ruth

Ruth, Nancy’s first driver, is a small but important example of ordinary decency in a world that has grown used to secrecy. She treats Nancy with casual kindness—talking about her daughter and books, offering sweets, driving safely—which contrasts starkly with Nancy’s sheltered dread and with the predation she later faces.

Ruth’s normality is a shock to Nancy, revealing what everyday social trust looks like and how alien it has become to someone raised under lockdown. She embodies the ordinary world Nancy wants to enter: not idealized, just human.

Anthony (“Ant”)

Ant is a brief encounter that crystallizes Nancy’s vulnerability and the ambient misogyny of the outside world. Flirtatious, intrusive, and sexually crude, he reads Nancy’s body as public property while also being unnerved when he suspects she resembles the murdered Nancy Liddell.

His terror at the resemblance suggests a society haunted by the past yet unable to process it honestly; copies are both familiar and uncanny, provoking desire, contempt, and fear. Ant’s warning about boys is hypocritical projection—he is himself the immediate danger—yet it also foreshadows the broader violence Nancy is rushing to prevent.

He is a reminder that even beyond the Scheme, the “real world” carries its own threats, especially for girls.

Mr Webb

Mr Webb, the baker, appears as a rare friendly villager and thus carries outsized symbolic weight. His ease with the boys suggests that compassion is possible even amid widespread suspicion and prejudice.

In a community trained to view Sycamore residents as oddities or contagion, Mr Webb represents unremarkable humanity: the sort of everyday kindness that could have altered the boys’ understanding of themselves if it were more common.

Mr Kendrick

Mr Kendrick, the shopkeeper who recoils from touching Vincent, embodies the village’s fearful complicity. His unease is not openly violent, but it enacts social exclusion and enforces the boys’ sense of being less than ordinary.

Kendrick’s behavior shows how prejudice can live in gestures rather than speeches, and how state secrecy fosters contagious suspicion. He is a small node in the wider network that keeps copies isolated, even once they step outside the flint walls.

Miss Ream

Miss Ream arrives after Mother Morning’s collapse and marks the institutional shift from secretive decline to crowded transition. With her, Captain Scott stops being a near-empty sanctuary for three boys and becomes an intake site filled with displaced children from other Homes.

She represents the new regime of management—less maternal, more administrative—tasked with stabilizing a system already morally bankrupt. Even without much detail, her presence signals a turning of eras: the old Mothers’ intimate surveillance gives way to a broader, more impersonal institutional aftermath.

Themes

Manufactured lives and the ethics of creating “copies”

From the first scenes at Captain Scott, human life is presented as something planned, regulated, and reproduced on purpose rather than arriving through ordinary family ties. Vincent and his brothers grow up in an institution designed to look nurturing, yet every element of that nurture is also a control mechanism: clothes that mark them by color, lessons based on a state-approved history, bodies monitored for symptoms, and dreams written down as data.

The gradual revelation that they are “copies” reframes their entire childhood. Their sense of being cherished is real, but it sits on top of a program that treats them as resources—children created to solve social and scientific goals.

The Sycamore Scheme’s logic is chillingly pragmatic: make companion children for lonely citizens, make test subjects for medication, make replaceable bodies for a system that wants benefits without responsibilities. The boys are taught that their world is safe and special, but the safety is conditional on obedience, and the “specialness” is tied to usefulness.

The repeated euphemism of being “sent to Margate” shows how bureaucracies hide cruelty behind pleasant language when the people harmed are seen as less than fully human. The later museum exhibit in Margate confirms that these were not accidents or isolated moral failures, but a designed pipeline from birth to disposal.

The Book of Guilt uses this structure to ask whether a society that can copy humans will ever resist ranking some lives as expendable. It also presses a harder question: if a child is created for a function, what obligations does the creator owe?

The novel suggests that the technological act of copying is not the real horror by itself; the horror is the political and emotional permission it gives to treat a person as a trial, a contingency, or a replacement. By the end, legal rights for copies arrive slowly, not because the system grows kinder on its own, but because those who were once made into objects insist on being seen as people, even while carrying scars from having been engineered to serve.

Surveillance, discipline, and the soft face of control

Life in the Home is structured around routines that appear gentle but operate like a private police force. The boys are listened to, watched over, corrected, and recorded in ways that blur care with surveillance.

The Book of Dreams turns imagination into a daily report; the boys must narrate their inner lives in the present tense, while an adult writes each detail down for later review by Dr Roach. Even misbehavior is formalized through The Book of Guilt, which makes wrongdoing permanent, enumerable, and inheritable across generations of residents.

This isn’t a world where rules are only enforced through punishment; rules are enforced through shaping what the boys think a good child is supposed to be. They internalize neatness, posture, and the idea that their bodies may collapse if they fail to eat or exercise properly.

Control reaches into the past as well, through the rewritten World War II lessons that normalize “hard compromises” for the “greater good. ” By teaching a version of history that celebrates sacrifice and scientific progress, the mothers prepare the boys to accept their own sacrifice as natural.

Later, political authorities continue the same logic at a national scale. The Minister of Loneliness speaks in soothing language about companionship and adoption while defending secrecy and downplaying deaths.

Her vision of rehoming is presented as humane reform, but it also extends state control out of the Home and into households, with vetting, concealment, and public messaging. The system is never honest about what the boys are, because honesty would force accountability.

What makes the theme sting is how often control is delivered through affection. Mother Night’s warmth comforts Vincent, and the mothers’ devotion is not entirely fake.

Yet their love operates inside a scheme that depends on obedience and ignorance. The result is an emotional trap: the boys feel loyal to the mothers, even when that loyalty keeps them silent about cruelty, illness, and fear.

The Book of Guilt suggests that the most durable kinds of domination are not always loud or openly violent. They are quiet, daily, and wrapped in care—so people learn to cooperate with their own containment, and so those doing the containing can believe they are kind.

Confinement, protected childhood, and the cost of ignorance

Vincent’s childhood and Nancy’s upbringing mirror each other in a way that highlights how confinement can be sold as love. Captain Scott is surrounded by high walls with broken glass, described by Vincent as safe and enclosed.

Nancy’s bungalow is less grand, but the gate and the rules that keep her inside function the same way. Both spaces make the outside world feel dangerous, strange, and morally suspect.

The boys are told their health is delicate; Nancy is told the world is unsafe. These stories aren’t just excuses for staying home.

They are training narratives that define identity: to be a Sycamore boy is to be fragile and managed; to be Nancy is to be cherished and hidden. Each child grows up with a limited vocabulary for reality.

That’s why the boys’ first trips into Ashbridge feel like entering a different species of life, and why Nancy’s hitchhiking journey becomes a crash course in ordinary human behavior she was never allowed to practice. Confinement also distorts time and scale.

Nancy’s father’s model village offers a miniature fantasy of order that substitutes for real experience, while the boys inhabit a curated garden world of rituals and “offerings” that substitute for wider community. When either child confronts the real world, the gap between their protected knowledge and actual danger is brutal.

Ashbridge villagers react with suspicion and pity to the boys, and Nancy runs into predatory attention from Ant because she hasn’t learned the cues of adult threat. The irony is that the adults justify confinement as protection, yet the harms that follow are largely produced by that very confinement.

If the boys had been taught the truth earlier, they might have had defenses against exploitation. If Nancy had been allowed friends and school, her parents’ obsession might not have turned into near-murder.

The theme reaches its peak when Nancy rescues William. Her decision to break out, cross distances, and climb the Home’s wall shows protective childhood collapsing under the weight of reality.

In The Book of Guilt, childhood innocence is not celebrated as a natural stage but shown as something engineered by adults—sometimes tenderly, sometimes cruelly—and always with consequences. The story argues that a protected childhood built on lies is not safety at all; it is delayed harm.

Guilt, complicity, and the long afterlife of trauma

Guilt in the novel is not limited to individual wrongdoing; it spreads through institutions, families, and time. The literal Book of Guilt at Captain Scott makes guilt into a written artifact, implying that morality has been bureaucratized.

Yet the deeper guilt is unwritten: the silent bargains people make to survive or to keep believing they are good. Vincent’s relationship with William captures this.

William’s private cruelties toward Cynthia and toward Vincent are clear, but Vincent hides them, partly out of fear and partly from a brother’s loyalty. That secrecy becomes an early lesson in complicity: caring for someone can mean becoming a container for their harm.

The mothers carry their own version of this. They genuinely love the boys, but they also administer injections, enforce dream reporting, and uphold the Home’s rules.

Their grief when the scheme ends does not erase their role in keeping it alive. Dr Roach embodies scientific complicity.

He frames the boys as his “life’s work,” a phrase that sounds affectionate until the reader sees how that work includes drug trials and fatal outcomes. Sylvia Dalton stands in the middle of political guilt.

She tries to end the Homes, yet she also bargains with Arthur Powell and uses the boys for her aim of recovering Nancy’s remains. Even when her intentions include empathy, she still treats their lives as pieces in a political match.

The Liddells’ guilt is rawer and more personal, shaped by loss that hardens into obsession. Their attempt to kill William is monstrous, but it is also the product of years of state deception and private grief that never healed.

The novel refuses to simplify guilt into villains and victims. Instead, it shows a ladder of decisions where each rung feels small at the time but leads to disaster.

The final museum visit makes guilt historical, forcing Vincent and Nancy to face not only what was done to them but how the whole society participated through silence, euphemism, or celebration. Vincent’s collapse in front of an entry connected to Jane underlines that guilt is not only about what others did; it is also about what one failed to prevent, what one misunderstood, and what one did while trapped inside a system.

The Book of Guilt paints guilt as something that survives the ending of any program. It remains in bodies, in memories, and in the stories people tell themselves to keep living.

Identity, individuality, and the struggle to be more than a source

The triplets’ existence raises a constant tension between sameness and selfhood. They are genetically identical, dressed in different colors, and trained in synchronized routines.

Their game of swapping shirts is playful on the surface, but it also reveals how fragile their sense of identity is—if a shirt can make someone “Vincent” or “William” for an hour, what is a self made of? The novel explores this tension through personality differences.

William’s sharpness, Lawrence’s sensitivity, and Vincent’s longing for order prove that identical bodies do not guarantee identical people. Yet the world around them keeps forcing the opposite idea.

Villagers see them as curiosities. The Sycamore Scheme calls them “copies,” a word that collapses personhood into origin.

Arthur Powell sees them as extensions of himself, preaching about protecting girls while quietly drawing them back into his own narrative. Even Nancy discovers that her own life is shaped by someone else’s template.

She is a copy of the murdered Nancy Liddell, raised by parents who cannot separate her from their dead child. Her parents’ staged photographs show this clearly: they are not recording who she is becoming, they are trying to resurrect who they lost.

Against this pressure, the characters fight for individuality in small, stubborn ways. Vincent’s soap carving is a private act of creation that belongs only to him.

Nancy’s decision to leave home and save William is a declaration that she is not a substitute object but a moral actor. The later campaign for copies’ rights extends this struggle from the personal to the legal: recognition by law becomes recognition of selfhood.

Still, the novel keeps the cost visible. William’s mutilation and silence represent identity violently taken away.

Lawrence’s disappearance shows how some selves are crushed by what they learn. Vincent and Nancy’s adult life is not a neat triumph of individuality; it is a daily effort to live as whole people while carrying the knowledge that their origins were engineered and their childhoods controlled.

The Book of Guilt ultimately treats identity as an achieved condition rather than a given one. Being a person here is not automatic; it is fought for, argued for, and rebuilt after systems try to reduce a human being to a function, a memory, or a source.