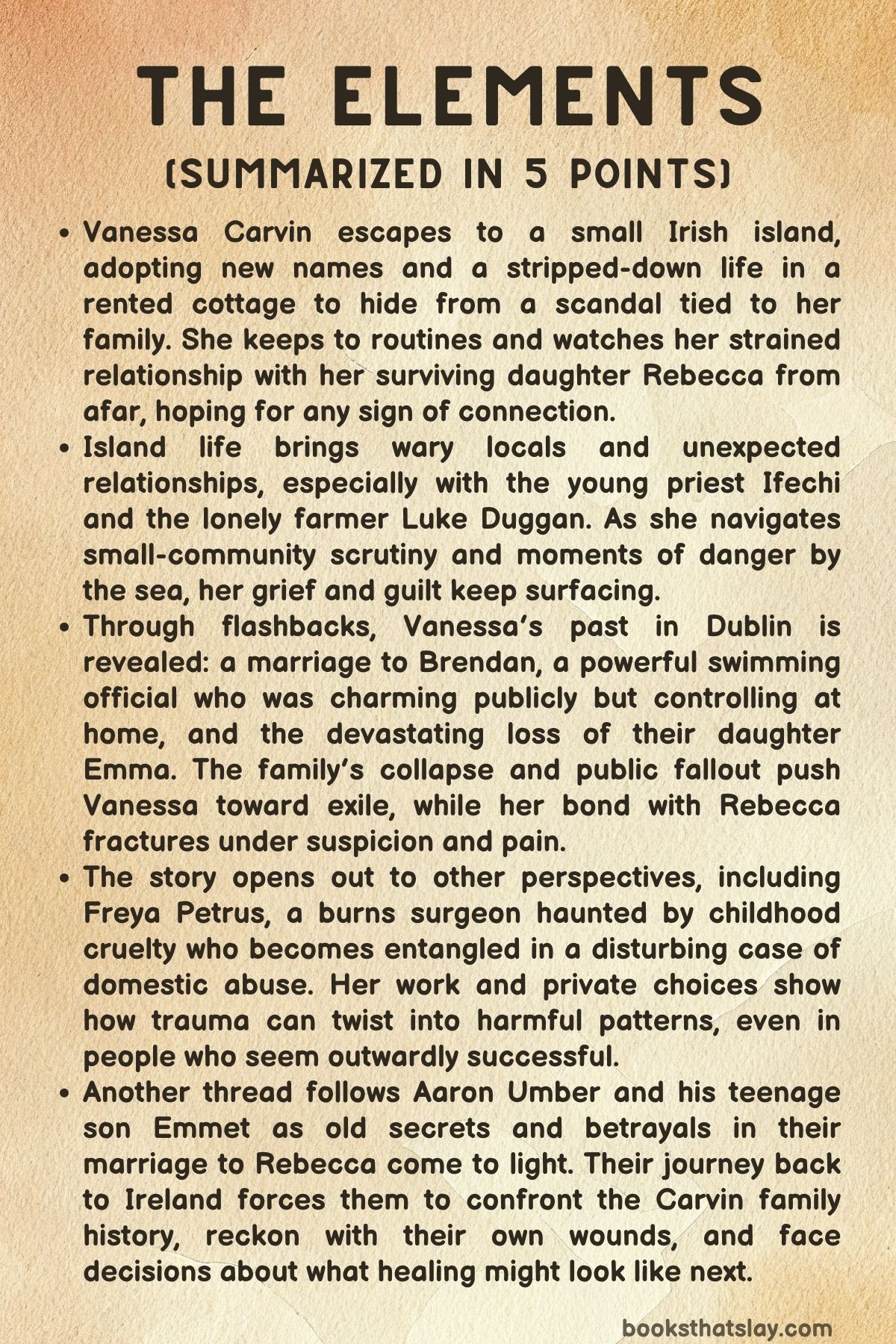

The Elements by John Boyne Summary, Characters and Themes

The Elements by John Boyne is a contemporary novel that follows three people whose lives are marked by harm, secrecy, and the search for a way to keep going. Set partly on a remote Irish island and partly in Dublin, Sydney, and a hospital burns unit, it looks at how public scandal and private trauma shape identity.

The story moves between past and present to reveal what each character did, endured, and failed to see. Boyne builds a quiet, tense narrative about guilt, survival, and the fragile work of rebuilding trust—both with others and with yourself.

Summary

Vanessa Carvin arrives on a small Irish island alone, intent on disappearing. She sheds her old name in layers, calling herself Hale and then Willow Hale, and alters her appearance so no one will connect her to the woman the country thinks it knows.

The cottage she rents is bare and old-fashioned, with no comforts or connection to the outside world. The sparseness suits her.

She wants quiet, distance, and the chance to live without being watched. The islanders, curious and cautious, assume she is a writer on retreat, but Willow refuses to explain herself.

Her days become strict routines: early walks along the cliffs, simple meals, short trips into the village, and long hours of reading in silence.

Even in exile, she cannot fully escape her old life. She checks her phone daily to see if her surviving daughter, Rebecca, has been online.

Sometimes Rebecca blocks her, sometimes she reappears, and Willow reads these small digital signs like tides. Her worry is constant, and the absence of contact feels like punishment she expects but cannot bear.

A young priest, Ifechi Onkin, new to the island and originally from Nigeria, introduces himself warmly. Willow tells him she is not religious, but he still offers her the church as a space for calm.

Their conversations are light on the surface, yet Willow keeps herself guarded. Her presence on the island is not about faith; it is about running from shame and grief.

She carries a history that has made her notorious: her husband Brendan Carvin, once a celebrated swimming administrator, is now in prison for abusing teenage girls under his authority. Their older daughter, Emma, is dead.

The public sees Willow as part of the story, and she has come here so that story cannot reach her.

Island life presses in anyway. Mrs.

Duggan, a blunt neighbor, storms into Willow’s cottage demanding the cat she calls Bananas. The visit turns into an interrogation.

Mrs. Duggan boasts about how locals once forced a gay couple to leave the same cottage.

Willow pushes back against her cruelty, stunned by how proudly it is offered. The exchange makes clear that the island protects its own version of order, and newcomers are tolerated only on local terms.

Through memories, the shape of Willow’s past emerges. Brendan had been charming to outsiders but controlling at home, mocking her, policing her choices, and treating her as an accessory to his public image.

Their struggle to conceive was poisoned by his accusations. Eventually they had two daughters.

Emma was lively and easy; Rebecca’s early years were harder, but the sisters became inseparable. On a family holiday, Emma drowned, leaving a hole in the family that never healed.

Later, as Brendan’s crimes came to light, another truth formed: Emma had been abused by her father before her death. Rebecca believes her mother should have known.

One night on the island, Willow swims alone in freezing darkness, pulled toward the sea that has taken so much from her. She returns shaken, sensing someone watching from the Duggan farm.

Instead of hiding, she walks home naked, refusing to be shamed by another set of eyes. Luke Duggan, Mrs.

Duggan’s shy adult son, later comes to apologize. He insists he was only outside smoking and warns her about the danger of night swimming.

His awkward kindness becomes a small foothold for her in the community. They share whiskey, talk about loneliness, and drift toward intimacy, both hungry for connection and unsure what it means.

Willow also forms a wary acquaintance with Tim Devlin, owner of the island’s newer pub. Tim eventually reveals he knows exactly who she is.

He tells her Brendan’s sentence was twelve years and adds his own confession: he once killed his wife in a drunk-driving crash and served time for it. Willow explodes at his attempt to trade guilt like currency.

She is tired of men asking to be forgiven while women are left with ruin.

The island’s tensions rise when a teenage boy, Evan Keogh, takes his father’s boat and goes missing at sea. The search brings everyone out.

Evan is found with a bruised face, and the truth behind his flight is hinted at: fear of his father, and a life forced into roles he does not want. Willow comforts Evan’s mother, Maggie, and sees another family cracking under expectations and silence.

A minister campaigning during a general election visits the church, and Willow recognizes him from her former world. Lucy Wood, a young woman, publicly challenges him for supporting Brendan in the past.

The minister dodges responsibility, then turns on Willow, calling her an “enabler” in front of the islanders. The accusation reopens everything she tried to bury.

During a storm, Brendan calls her from prison. He insists he is innocent and demands money for an appeal.

Willow finally says aloud what she believes: that he abused the girls and Emma, and that Emma’s death was not an accident but a decision shaped by what he did. He lashes out, and she cuts the call.

She reaches out to Rebecca with a desperate text. Rebecca replies, “There is no such person.

” The rejection lands like a door slammed forever. After the storm passes, Willow finds Bananas dead outside, another small loss added to the pile she already carries.

The narrative shifts to another life: Freya Petrus, a burns surgeon in Dublin. As a child, she was buried alive in a construction site in Cornwall, an event that left her terrified of enclosed spaces and quietly unstable beneath her competence.

At work she meets George Eliot, a fourteen-year-old desperate about his best friend’s failing kidney transplant. Freya holds to the rules of medicine, but the boy’s fear echoes her own childhood helplessness.

Freya treats Vidar Forsberg, a four-year-old with severe burns and a history of injuries. She is certain the harm is deliberate.

Confronting the parents, she discovers Sharon, the mother, is violent toward both her son and her husband Börje. Freya pushes them toward safety, but the case also sharpens something darker in her.

Her childhood tormentors in Cornwall were two wealthy twins who buried her and walked away. The rage she never resolved has grown into a secret pattern: she lures teen boys into her apartment, staging small humiliations as a twisted repayment against a world that once trapped her.

Her profession saves children by day; her nights are driven by revenge.

A third thread follows Aaron Umber, a medical student working with Freya and married to Rebecca Carvin in Sydney. Aaron’s past holds its own wounds, including sexual abuse in his teens.

When an older Irishman named Daniel shows up at his apartment, Aaron slowly realizes he is Brendan Carvin using a false identity. Aaron throws him out, and Rebecca’s terror confirms the danger Brendan still poses.

Soon after, Aaron travels to Ireland with his teenage son Emmet. They are heading to the island for Vanessa’s funeral.

Emmet is confused by the secrecy and anger, but Aaron decides he cannot keep the family history buried. He tells Emmet the truth about Brendan’s crimes and Emma’s suicide.

Emmet is devastated, but the honesty draws father and son closer.

On the island, they find Rebecca with her partner Furia Flyte, a now-famous novelist who once disrupted Aaron and Rebecca’s marriage. Despite old hurt, the reunion is tender because of Emmet.

The funeral is small. Ifechi speaks of Willow/Vanessa as a woman who came seeking peace and chose to remain where she found it.

In the days after, Rebecca and Aaron talk openly about their failures, their trauma, and the possibility of doing better for Emmet. Rebecca admits she wants to rebuild her bond with their son and tells Aaron he deserves love that is not conditional.

The island, with its harsh weather and quiet mornings, becomes a place of reckoning for the living. Aaron swims alone in the Atlantic, feeling both grief for Vanessa and a pull toward stillness he has not known in years.

He decides to stay for a long while, not to vanish as Vanessa did, but to heal in the open air she left behind. In the end, the three lives circle the same question: what it costs to survive, and what it takes to stop carrying harm forward.

Characters

Vanessa Carvin / Hale / Willow Hale

Vanessa, who reinvents herself first as Hale and then as Willow Hale, is the emotional core of The Elements. Her self-exile to the Irish island is not a quirky retreat but a survival strategy: she is fleeing public shame, unbearable grief, and her own sense of complicity in what happened to her daughters.

The radical changes she makes to her appearance and name signal both a desire to disappear and a fragile hope that a different life might still be possible. On the island, her sparse routine—walking, reading, eating quietly, checking her phone—shows a woman trying to control what little remains controllable after a life defined by betrayal and loss.

She is guarded with others because every interaction risks pulling her back into the identity she is running from. Yet her guardedness isn’t coldness; it’s a form of triage, a way to stay alive when her mind keeps circling Emma’s death and Rebecca’s rejection.

Vanessa’s moral struggle is one of the novel’s sharpest edges: she did not commit Brendan’s crimes, but she lived beside them, missed warnings, and let herself be reassured when she should have pressed harder. Her anger, especially toward Tim Devlin and Brendan, is the anger of someone who refuses easy absolution—not for them, and not fully for herself.

By the end, her choice to live and die on the island turns exile into a kind of agency: she cannot undo the past, but she can decide where her pain is held and how her story closes.

Rebecca Carvin

Rebecca is the surviving daughter shaped by a double rupture: the loss of her sister and the revelation of her father’s abuse. Her relationship with Vanessa is a battlefield of grief and blame, and her blocking and unblocking of her mother online becomes a raw, modern expression of that conflict—she wants distance, but she also cannot detach completely.

Rebecca’s anger is not petty; it’s the fury of someone who feels her whole childhood was contaminated, and that her mother failed to protect Emma. She carries a protective, almost fierce love for her own son Emmet, yet even that bond has frayed under the weight of trauma and the complicated fallout of her relationship with Aaron and Furia.

Rebecca’s return for Vanessa’s funeral shows that her rejection of her mother was never simple hatred; it was grief hardening into self-defense. When she thanks Aaron for telling Emmet the truth, she reveals a buried desire for honesty and repair, suggesting that while her wounds remain open, she is no longer willing to live inside denial.

Rebecca embodies the novel’s question of how to live after harm: she cannot rewrite what happened, but she can choose whether the future will be built from silence or from truth.

Emma Carvin

Emma exists largely through memory, yet she is a powerful presence because she represents both innocence lost and the cost of silence. As a child she is described as joyful and easy, the bright center of the family, which makes her later suffering feel even more devastating.

Her request for a bedroom lock is a chilling early signal that something was wrong long before Vanessa understood it; it marks Emma as perceptive and frightened, and it quietly indicts the adults who minimized her fear. Her death—first framed publicly as drowning and later revealed as suicide by swimming out to sea—turns water into a symbol of both beauty and annihilation throughout The Elements.

Emma’s story is not only tragedy; it is also the moral axis of the novel. The way different characters respond to her death exposes their character: Vanessa’s guilt and grief, Rebecca’s rage, Brendan’s denial, and Aaron’s belated honesty with Emmet.

Emma is the silence that the living must learn to speak around, and her absence drives the book’s insistence that harm ignored becomes harm repeated.

Brendan Carvin / “Daniel”

Brendan is the novel’s embodiment of charismatic cruelty and institutional protection. Publicly celebrated as a sports administrator, privately he is controlling, sexist, and predatory, creating a split reality that traps Vanessa in doubt and rationalization for years.

His manipulation is subtle when it needs to be—recasting Peggy as a drunk, turning fertility struggles into accusations against Vanessa—and violent when challenged. Even in prison he clings to the posture of victimhood, demanding money for appeals and insisting he was set up, showing how deeply entitlement and self-deception define him.

His decision to appear under the alias “Daniel” in Aaron’s apartment is another form of violation: he uses disguise not to change but to infiltrate, to reclaim access to the family he shattered. Brendan’s greatest menace is not only what he did but how expertly he trained others, especially Vanessa, to doubt their own instincts.

In The Elements, he is less a mystery than a warning about the kinds of harm that flourish when charm, power, and societal convenience collaborate.

Fr. Ifechi

Fr. Ifechi, the young Nigerian priest, functions as a moral counterpoint to the island’s suspicion and to Vanessa’s internal collapse.

His warmth and lightly teasing manner lower defenses without demanding intimacy, which is why Vanessa can tolerate him even as she rejects religion. He represents faith not as dogma but as presence—he offers the church as a quiet refuge rather than a battleground of belief.

His refusal to betray confidences about Tim Devlin or Evan Keogh shows integrity and an understanding that healing requires safe spaces. Ifechi’s outsider status mirrors Vanessa’s, yet he has chosen rootedness and service rather than disappearance, which makes him a quiet model of how to survive painful histories without being consumed by them.

His eulogy at Vanessa’s funeral reframes her exile as a search for healing, validating her as more than a scandal or a grief-struck mother. Through Ifechi, The Elements suggests that compassion can be firm, hopeful, and non-intrusive all at once.

Mrs.

Mrs. Duggan is the island’s harsh gatekeeper, a woman who polices belonging with righteous certainty.

Her intrusion into Vanessa’s cottage over the cat is comic on the surface, but beneath it lies a deeper need to control the boundaries of the community. She is proudly homophobic and boasts about driving away past tenants, revealing how prejudice can be normalized as local tradition.

Yet her complexity shows in the way she grudgingly softens when challenged—she does not transform, but she is not unmovable stone either. Mrs.

Duggan’s interrogation of Vanessa’s background reflects the island’s collective anxiety about outsiders bringing disruption, and also hints at her personal fear of change and shame. She is both a product of her culture and an active enforcer of it.

In The Elements, she embodies the threat of small communities when they decide safety means sameness, but also the possibility, however limited, that confrontation can crack long-held certainties.

Luke Duggan

Luke is outwardly shy and awkward, but he becomes the island’s most intimate bridge to Vanessa’s fragile return to human connection. As the youngest of eight siblings left behind to run the farm, he is weighed down by duty and loneliness, living in a cycle of work that leaves little space for desire or self-exploration.

His apology for seeing Vanessa naked is genuinely tender rather than performative, and his warning about the sea reveals a protective instinct that contrasts sharply with the careless men in Vanessa’s past. Luke’s anger at how islanders treated former tenants shows that he is not aligned with his mother’s cruelty, even if he can’t fully escape her shadow.

His growing attraction to Vanessa is not framed as a rescue fantasy; instead it reads like two bruised people testing the possibility of warmth in a cold place. Luke’s presence highlights one of The Elements’ quieter truths: that survival sometimes begins with simple kindness between strangers.

Tim Devlin

Tim is a study in guilt, confession, and the hunger to be forgiven. As the owner of the new pub, he is firmly part of island life, yet he carries the stigma of having killed his wife in a drunk-driving crash and served years in prison.

His physical tic in church points to trauma that never healed, and his loneliness is palpable in how he seeks out Vanessa’s company. Tim’s revelation that he recognized Vanessa immediately demonstrates both perceptiveness and a willingness to hold another person’s secret without exploiting it.

However, his conversation with Vanessa also exposes a dangerous human impulse: to seek solidarity in suffering as a shortcut to absolution. When Vanessa rebukes him for expecting sympathy, she forces him—and the reader—to confront the difference between carrying guilt responsibly and using it to demand emotional comfort.

Tim is not villainous, but he is deeply flawed, and his story contributes to The Elements’ broader portrait of people who must learn to live with what they have done.

Evan Keogh

Evan is a teenager caught between selfhood and coercive expectations. His desire to paint rather than pursue football signals a sensitive, imaginative interior life that doesn’t align with his father’s vision of masculinity.

His disappearance at sea is less a reckless adventure than a symptom of fear and suffocation. Returning with a black eye underscores that his conflict is not abstract—it is physical, immediate, and ongoing.

Evan’s rejection of his mother after being rescued suggests the toxic pull of shame: even love can feel dangerous when a young person believes they are the problem. In The Elements, Evan becomes a mirror to Emma’s unspoken terror and a reminder that harm inside families often announces itself through desperate acts long before it is named.

Maggie Keogh

Maggie is a mother navigating a dangerous household with limited power. Her private confession to Vanessa that Evan is frightened, and that Charlie pushes him toward football, shows both clarity and helplessness.

She loves her son fiercely, but her fear of confronting her husband directly reveals how abuse structures silence not only for victims but for those trying to protect them. Maggie’s decision to tell Vanessa the truth is an act of quiet courage, and it aligns her with the novel’s women who refuse to keep swallowing violence.

She represents the painful middle ground between seeing what’s wrong and being able to stop it, and through her, The Elements shows how even good people can become trapped in systems of fear.

Charlie Keogh

Charlie is a more muted version of the controlling men in the novel, but his influence is still corrosive. His insistence that Evan pursue football, and the fear it evokes, positions him as a father who values a socially approved image over his child’s inner life.

The black eye Evan returns with suggests that Charlie’s authority is enforced through intimidation or violence. Unlike Brendan, Charlie is not painted as a public monster; he is ordinary in a way that makes him more unsettling because he shows how coercion can hide in everyday family expectations.

In The Elements, Charlie illustrates that harm does not always wear the mask of notoriety; sometimes it looks like a father insisting “this is what you will be.

Minister Jack Sharkey

Jack Sharkey represents the machinery of power that enables men like Brendan. His visit to the church during the election situates him in the realm of performance, where politics becomes a stage for moral evasions.

When Lucy Wood confronts him, his response—praising Brendan’s professional success while condemning abuse in general terms—exposes the classic strategy of institutions: protecting reputations through vagueness. His recognition of Vanessa and the word “enablers” are calculated cruelty, shifting blame onto a woman already destroyed by association.

Jack is not personally central to the family’s tragedy, yet he is structurally essential to it. Through him, The Elements indicts systems that congratulate themselves for outrage while quietly preserving the conditions that make abuse possible.

Lucy Wood

Lucy is a brief but electric presence, a young woman who insists on naming complicity out loud. Her public challenge to Jack Sharkey gives voice to victims who are often forced into silence, and her courage disrupts the island’s polite deference to authority.

Lucy’s role is less about her personal backstory and more about what she represents: refusal to let power rewrite the narrative. In The Elements, she is an embodiment of the cultural shift Vanessa herself is struggling to catch up with—a world where survivors and allies demand answers in daylight, not whispers.

Freya Petrus

Freya occupies a different strand of the novel, yet thematically she dramatizes trauma’s afterlife. A skilled burns surgeon, she is competent, sharp, and used to controlling chaos in the hospital, but her childhood burial alive has left her claustrophobic, hypervigilant, and emotionally isolated.

Her contempt for Aaron’s inexperience and her impatience with colleagues show how trauma can calcify into irritability, a defense against closeness. Most disturbingly, Freya’s compulsion to lure teenage boys is framed as vengeance rooted in her past with the Teague twins, but it reveals how victimhood can metastasize into perpetration.

She constructs rituals—forgetting her purse, shaking the Coke can—to create inevitability, as if reenacting a script she cannot rewrite. Freya is not offered easy sympathy, yet neither is she reduced to a monster; she is a portrait of what happens when pain is never processed and instead becomes identity.

In The Elements, her storyline expands the moral landscape by refusing the simple binary of harmed versus harmful.

Aaron Umber

Aaron is both a medical trainee and a man trying to learn how to father, love, and live honestly after years of emotional drift. In the hospital he appears immature and irritating to Freya, but his willingness to help Börje and Vidar shows a genuine ethical backbone.

His relationship with Rebecca is tender but complicated by long-standing sexual distance, his own unresolved trauma, and the gravitational pull of Furia. Aaron’s confrontation with Brendan—recognizing him beneath the false name Daniel and throwing him out—marks a crucial turning point where Aaron chooses protection over politeness.

As a father to Emmet, he is flawed but striving: he invades his son’s privacy out of anxiety, yet later confesses his own abuse and listens when Emmet speaks. Aaron’s arc is one of slow moral awakening, moving from avoidance to truth-telling.

By deciding to stay on the island to heal, he accepts that survival requires time and humility. In The Elements, Aaron represents the possibility of repair when someone stops running from what shaped them.

Emmet Umber

Emmet is fourteen, poised between childhood dependence and teenage skepticism, and the journey to Ireland becomes a brutal acceleration into adulthood. His sulkiness early on reads as normal adolescent resistance, but it also masks insecurity about being unwanted by his mother and confusion about his family’s fractures.

When Aaron tells him the truth about Brendan and Emma, Emmet’s physical reaction—vomiting, then steadying himself—shows a young person whose body registers trauma before his mind can organize it. Yet his response is also courageous: he insists they keep going, then hugs Rebecca fiercely when they reunite.

Emmet’s willingness to hear Aaron’s confession of abuse, and his later suggestion that they rebuild as a family with Rebecca and Furia, shows a maturity born from empathy rather than cynicism. In The Elements, Emmet is the future generation forced to inherit painful truths, and his openness suggests the possibility that honesty can break cycles instead of repeating them.

Furia Flyte

Furia is a catalyst figure whose presence exposes fault lines in Aaron and Rebecca’s marriage. As an aspiring writer turned bestseller, she symbolizes both ambition and the dangerous intimacy of being seen clearly.

Aaron falls for her because she listens to the parts of him that feel starved of love, but Furia refuses to be an escape hatch; she pushes him to confront whether his marriage can survive, and when he declares love, she reveals her own love for Rebecca. Her choice unsettles both of them because it refuses heterosexual scripts of rivalry and possession.

At the funeral she is calm, present, and no longer a destabilizing secret, suggesting that her maturation has involved accepting complexity without melodrama. Furia is not framed as villain or savior; she is a reminder that desire doesn’t arrive politely, and that truth can hurt even when it is honest.

In The Elements, she helps shift the story from betrayal toward clarity.

George Eliot

George is a vulnerable, earnest fourteen-year-old whose fear for Harry pulls Freya toward the edge of her professional boundaries. His willingness to approach a stranger for help shows desperation but also emotional courage.

He articulates the terror of watching someone you love suffer without being able to fix it, and his breakdown on the bench strips away any pretense of teenage toughness. George’s scene deepens Freya’s characterization by showing the version of herself that is still capable of tenderness.

In The Elements, he represents innocence under threat, anchoring the hospital storyline in a real, immediate human need for reassurance.

Harry Cullimore

Harry is mostly offstage, yet his failing kidney transplant and long wait for another organ create the emotional stakes that shape George’s storyline. He is the absent friend whose suffering radiates outward, illustrating how illness turns not only a patient’s life but an entire adolescent friendship into a territory of fear and hope.

In The Elements, Harry’s role is to embody fragility and the helplessness of those who watch it.

Vidar Forsberg

Vidar, a four-year-old burn patient, is one of the novel’s starkest portrayals of voiceless vulnerability. His severe injury and the pattern of past “accidents” signal ongoing abuse, and his presence forces Freya and Aaron into moral action.

Vidar himself is not a developed personality in the narrative, but that is the point: he is a child whose identity is being overwritten by violence before he can form it. In The Elements, he stands for the youngest victims who rely entirely on adults to notice, intervene, and speak.

Börje Forsberg

Börje begins as a defensive father performing normalcy, but quickly unravels into a desperate, bruised victim of his wife’s control. His plea for help after Sharon leaves shows a man trapped by shame and fear, unsure whether anyone will believe him.

His love for Vidar is evident in his terror of what will happen if the truth stays hidden. Börje’s disclosure to Freya is a moment of trust that reorients the hospital storyline toward intervention.

In The Elements, he complicates gendered assumptions about abuse, showing how harm can flow against expected power lines.

Sharon Forsberg

Sharon is one of the most chilling figures in the hospital arc because of her casual detachment. She treats Vidar’s injuries as inconveniences, interrupts the confrontation with a work call, and handles her child roughly, signaling a coldness that goes beyond stress.

Her abuse of both Vidar and Börje is implied as systematic and coercive, and her brisk insistence on leaving highlights how abusers often wield confidence as camouflage. Sharon’s presence in The Elements widens the novel’s portrait of cruelty beyond male perpetrators, underscoring that abuse is a behavior, not a gender trait.

Hugh Winley

Hugh is a small but unsettling figure who illustrates how predatory entitlement can hide behind neighborly familiarity. His pushy attempt to corner Freya and his reference to meeting her “nephew” make him feel invasive, and his presence contributes to Freya’s sense of being watched and trapped.

In The Elements, Hugh is part of the ambient environment of threat that Freya navigates, a reminder that boundaries are constantly tested.

Rufus

Rufus is a fourteen-year-old boy chosen by Freya for her ritual of vengeance, and his ordinariness is what makes the scene horrifying. He is polite, trusting, and used to neglect—his mother’s habit of leaving him money and disappearing makes him vulnerable to anyone offering attention.

Rufus embodies the way predators exploit loneliness, and he becomes a living echo of Freya’s own childhood helplessness. In The Elements, he is a victim not because he is reckless, but because he is a child in a world where adults can weaponize kindness.

Beth Petrus

Beth, Freya’s neglectful mother, is a shadow presence shaping Freya’s origin story. Her inattentiveness and emotional absence leave Freya hungry for validation, which the Teague twins exploit.

Beth doesn’t commit overt violence, but her neglect creates fertile ground for it. In The Elements, she represents the quieter parental failures that can be just as formative as active cruelty.

Arthur and Pascoe Teague

The Teague twins are the original architects of Freya’s trauma. Privileged, mocking, and fascinated by cruelty, they draw Freya into dangerous games and psychological manipulation, climaxing in her being buried alive.

Their behavior suggests not childish mischief but deliberate sadism nourished by wealth, boredom, and a warped family culture. Even though they are in Freya’s past, they remain psychologically present through the vengeance she enacts.

In The Elements, they show how early harm can be both senseless and life-defining, and how perpetrators in childhood can ripple into future violence.

Bananas

Bananas, the visiting cat, is more than local color. The animal becomes a small axis of connection between Vanessa and the island, pulling her into reluctant social contact and exposing the community’s surveillance through Mrs.

Duggan. Bananas also offers Vanessa a routine of care that contrasts with her helplessness with her daughters, letting her practice tenderness without the risk of rejection.

The cat’s death in the storm is a symbolic blow, stripping away one of Vanessa’s last anchors and emphasizing how fragile her recovery is. In The Elements, Bananas embodies innocence, companionship, and the cruel randomness of loss.

Ron

Ron appears briefly at the funeral as Vanessa’s husband, but his main narrative role is to remind readers of what remains unresolved around Brendan’s legacy. His presence among Rebecca and Furia suggests a new, awkward constellation of family in the wake of devastation.

In The Elements, Ron functions as a marker of the life Vanessa left behind and the complicated survivors still orbiting her story.

Jake, Belinda, and Damian

Jake and Belinda enter Aaron’s memories as part of the Sydney circle where Aaron and Rebecca’s marriage began to fray. Their home and party give space for Aaron to meet Furia, making them quiet enablers of the turning point that follows.

Damian, their son and Emmet’s friend, anchors Emmet’s life back in Australia and appears through the prank photos Aaron finds. In The Elements, this trio represents ordinary community life—friendships and families that continue even as private trauma shifts beneath the surface.

Themes

Exile, self-erasure, and the search for anonymity

Vanessa’s arrival on the island under the invented name Willow Hale is less a fresh start than a controlled disappearance. The new identity, shaved hair, and bare Dooley cottage let her shrink her life down to the simplest possible shape, as if stripping possessions and recognition could also strip away memory and blame.

Her daily routines—walking cliffs at dawn, bathing, reading, eating lunch alone—work like a kind of personal witness protection, a way to inhabit time without being interrogated by it. Yet the island, for all its size and remoteness, refuses to be a blank slate.

People notice her immediately, speculate about her past, and quietly enforce the social rule that outsiders must explain themselves if they want acceptance. Through Mrs.

Duggan’s intrusive questioning and proud recollection of forcing out a gay couple, the story shows how exile is rarely a purely individual choice; it is also shaped by the gatekeeping of communities that decide who gets to belong. Vanessa wants to exit the story told about her on the mainland—the notorious wife linked to a convicted abuser, the mother of a dead child, the woman blamed in tabloids and whispers.

But anonymity cannot abolish relationship. Her constant checking of Rebecca’s online status, the sting of being blocked, and her fear when Rebecca disappears from view show that even in hiding she remains tethered to motherhood and to the need to be seen by the one person whose gaze matters most.

The island becomes a paradoxical space: it protects her from society’s noise while amplifying her inner one. Her nighttime swim in freezing darkness is the extreme expression of that paradox.

Water is both the instrument of her family’s ruin and the place where she seeks to vanish from pain; choosing it again is almost like rehearsing her own ending. The confrontation with the watcher at the Duggan farm and her decision to walk home naked instead of feeling shamed signals that exile can turn into a fragile kind of agency.

She cannot control how the mainland names her, but she can control how she moves through this new place and whether she will accept or resist the terms of her invisibility.

Grief, survival guilt, and the afterlife of loss

Loss in The Elements is not a single tragedy but a continuing climate that shapes thought, behavior, and morality. Vanessa’s grief over Emma is layered: she mourns the daughter she lost, the sister Rebecca lost, and the version of family life that died with Emma.

Because Emma’s death is tied to water and later revealed as suicide connected to abuse, grief becomes inseparable from questions of cause, responsibility, and what should have been noticed earlier. Vanessa’s memories of refusing Emma a bedroom lock and of ignoring Peggy’s vague warning play like reruns that cannot be edited; survival guilt feeds on those moments of ordinary dismissal.

She does not merely miss her child—she re-lives the conditions that made her child unsafe. This gives grief a punitive edge, as though every memory is evidence in an internal trial.

The narrative mirrors Vanessa’s private burden with Tim Devlin’s confession about killing his wife while drunk. His story exposes another angle on guilt: the temptation to seek forgiveness through disclosure and to imagine that pain can be balanced by being honest about it.

Vanessa’s furious response to Tim shows how grief can sharpen one’s moral vision and impatience, especially toward the patterns of male self-excuse that have already devastated her life. The missing-at-sea episode with Evan Keogh extends grief beyond Vanessa’s family.

The island’s collective panic and Maggie’s quiet fear that Evan fled because he is scared illuminate how communities carry grief in advance—anticipating loss because they know how easily the sea, fathers, and expectations can swallow the young. Even Bananas’s death during the storm is not incidental; it adds another small, helpless life to the ledger of things Vanessa cannot save.

Grief repeatedly pushes characters toward the edge of self-destruction—Vanessa’s suicidal swim, her wandering into the storm singing, Aaron’s lonely contemplation, Freya’s compulsions—but it also generates moments of stubborn survival. Vanessa keeps returning to daily life, even if only in fragments.

Aaron decides to tell Emmet the full truth, accepting the risk of hurting him to prevent a future built on silence. By the end, grief is depicted as something that never resolves neatly.

Instead, it becomes a force that can either freeze life into shame and isolation or, when faced directly, open a path toward painful honesty and continued living.

Complicity, silence, and accountability in systems of harm

The story insists that abuse is rarely sustained by a single perpetrator alone; it survives through the structures and people that look away, rationalize, or protect reputation. Brendan Carvin’s public charm and professional power in the swimming world allow him to control how he is perceived, and those perceptions shape Vanessa’s blindness.

Her acceptance of his dismissals—about Peggy’s warnings, about odd behavior, about the sudden sabbatical—illustrates how complicity can form without intention. She is not portrayed as evil or indifferent; she is portrayed as socialized, exhausted, and invested in a life that requires not asking too many questions.

This is precisely why the theme is uncomfortable. It presses the reader to see how ordinary habits of trust, marital deference, and fear of social disruption can become the soil in which predation grows.

The confrontation in the church during the election sharpens this critique. Minister Jack Sharkey’s evasive answers about Brendan show political complicity at the institutional level: he praises professional success while treating abuse as an abstract tragedy, refusing to name his own enabling role.

His pointed warning to Vanessa about “enablers” is a cruel irony, since he is doing in public what she did in private—deflecting responsibility while safeguarding status. Vanessa’s later prison call with Brendan is a turning point because for the first time she names the harm plainly and denies him sympathy.

When she tells him that Emma swam out to sea and died by suicide, she makes truth the price of any continued connection. The theme also extends into other contexts: Freya identifying child abuse in Vidar’s injuries highlights a professional world where accountability requires both expertise and courage, and where failure to act has immediate bodily consequences.

Aaron’s recognition of Daniel as Brendan in his apartment is another test of accountability. He does not negotiate, excuse, or treat family ties as mitigating; he demands that Brendan leave and frames the loss of rights as earned by harm.

Even Rebecca’s estrangement from Vanessa can be understood through this lens—her refusal to speak to her mother is the punishment a child gives an adult who, in her view, did not protect her sister. Across these threads, The Elements argues that accountability is not a single courtroom verdict.

It is a continuous moral practice: the choice to notice, to refuse flattering narratives, to risk discomfort, and to say aloud what others prefer to keep unnamed.

Trauma, repetition, and the lure of vengeance

Trauma in the novel is shown as something that rearranges a person’s instincts, often pulling them toward patterns they consciously reject. Freya’s childhood burial in Cornwall produces obvious aftereffects—claustrophobia, panic in elevators—but the more disturbing consequence is her later compulsion to harm boys who resemble those who hurt her.

Her ritualized approach at Ramleigh Park, the deliberate forgetting of her purse, the prepared Coke, and the staged accident with Rufus’s shirt show trauma turning into choreography. She tries to reclaim power by recreating the scene of her own vulnerability with her on top, yet the act only deepens the trap of repetition.

This is not presented as a sudden transformation into monstrosity; it is presented as a slow development from neglect, humiliation, and betrayal into a distorted idea of justice. The theme is echoed in Brendan’s abuses, which are not explained away by his past but are situated within a broader reality where power and secrecy allow violence to persist.

Trauma also shapes those who are not perpetrators. Rebecca’s lifelong resentment toward her mother and her suspicion that Brendan also abused Emma demonstrate how trauma can fracture families into hard, brittle roles: the accused protector, the betrayed child, the ungrievable dead.

Aaron’s own teenage abuse, which he reveals to Emmet late in the book, has quietly shaped his marriage, his sense of self-worth, and his susceptibility to Furia’s attention. The narrative suggests that unspoken trauma does not disappear; it leaks into intimacy, parenting, and choice.

Even Vanessa’s nighttime swim can be read through this frame. She returns to the sea not because she has healed from Emma’s death but because trauma keeps calling her back to the place of loss, offering the false promise of resolution through repetition.

What complicates the theme is that repetition is not only destructive. The search for Evan, the shared wake, Emmet and Aaron’s honest conversations, and Rebecca’s tentative rebuilding of her bond with her son are also repetitions—rehearsals of care, truth, and presence meant to overwrite past silence.

By placing vengeance and healing side-by-side, The Elements shows trauma as a crossroads. One path tries to reverse the past through harm and control; the other accepts that the past cannot be undone, only faced, spoken, and carried differently forward.

Belonging, intolerance, and the moral weather of small communities

The island setting is not a backdrop; it is a moral ecosystem where belonging is monitored, negotiated, and sometimes weaponized. Mrs.

Duggan embodies this with her pride in chasing off the gay couple who once rented the cottage and her instinctive interrogation of Willow’s origins and marital status. Her behavior shows how small communities can convert familiarity into authority, using tradition and suspicion as tools to enforce conformity.

The island’s assumption that Willow must be a writer on retreat is another subtle form of control—a way of placing a stranger into a safe, legible category without granting her the right to remain undefined. Yet the narrative avoids treating the island as simply cruel or backward.

Luke Duggan’s anger at how outsiders were treated and his loneliness as the last sibling who stayed to keep the farm running reveal the costs of that policing even for insiders. Belonging on the island demands sacrifice: staying means inheriting duty and isolation; leaving means being spoken about as someone who abandoned home.

The pubs function as social barometers. The “new” pub feels lighter but is still shadowed by Tim Devlin’s past, while the old pub is where confessions, grief, and the community’s deeper memory gather.

The missing Evan episode exposes both the solidarity and the violence that can coexist in tight-knit places. Islanders mobilize to search, celebrate when he returns, and yet the boy’s black eye and frantic rejection of his mother suggest that the same community capable of rescue is also one where family pressure and potentially paternal brutality push a child toward escape.

The church scenes add another layer. Ifechi’s presence as a Nigerian priest in rural Ireland presents belonging as something that can be widened; he is welcomed enough to lead funerals and counsel locals while still being visibly different.

His gentle, firm refusal to violate confession boundaries models another kind of community rule—one based not on exclusion but on ethical care. Ultimately, the island tests Willow’s relationship with belonging itself.

She arrives wanting invisibility, but forms connections anyway: with Ifechi, Luke, Tim, Maggie, and finally with Rebecca and Emmet through the wake and funeral. The island’s moral weather is changeable.

It can freeze strangers out, but it can also offer a place where truth is spoken quietly, grief is held collectively, and damaged people are allowed to remain without performing a perfect story of who they are.

Healing through truth-telling and the slow rebuilding of family

By the end of The Elements, healing is not a miracle or a clean arc; it is the gradual effect of refusing further lies. Vanessa’s fiercest act of self-respect is not moving to the island but confronting Brendan on the phone and naming his abuse without hesitation.

That conversation breaks the spell of his denial and marks a shift from survival through silence to survival through truth. Her death soon after does not negate that movement; instead, it turns her life on the island into a final statement about wanting to live somewhere honest, even if briefly.

Aaron’s storyline continues this ethic. He chooses to tell Emmet the truth about Brendan’s crimes and Emma’s suicide while standing on the island, knowing the knowledge will injure his son’s innocence but also protect him from inheriting a sanitized family myth.

Emmet’s devastation is immediate, physical, and raw, yet it becomes the ground for a more real closeness between father and son. Their later conversation about Aaron’s own abuse extends the theme beyond one family secret; it shows truth-telling as a way of giving the next generation language and context instead of confusion and quiet shame.

Rebecca, too, begins to heal not by forgetting but by naming. Her anger at Vanessa remains, but she can still thank Aaron for telling Emmet the truth and admit her need to rebuild motherhood.

Even her partnership with Furia arrives at the wake not as scandal but as a living relationship set against the ruins of old ones—proof that love can re-form in unexpected shapes after betrayal. The funeral itself is a ritual of repair.

It gathers people who are fractured—Aaron, Rebecca, Emmet, Furia, Ron, and islanders who knew Willow—to occupy the same space, share memory, and accept ambivalent feelings without forcing them into a single attitude. Ifechi’s eulogy frames Vanessa’s time on the island as a choice toward healing, and his words allow others to see her not only as a figure in a public scandal but as a person who tried to live past sorrow.

Aaron’s decision to stay on the island for months or a year is the final expression of this theme. He is not escaping responsibility; he is choosing a setting where he can practice honesty, face his grief, and then return to Sydney with a different inner life.

Healing here is shown as something built from clear speech, imperfect forgiveness, and continued presence, even when the wounds that made healing necessary never fully go away.