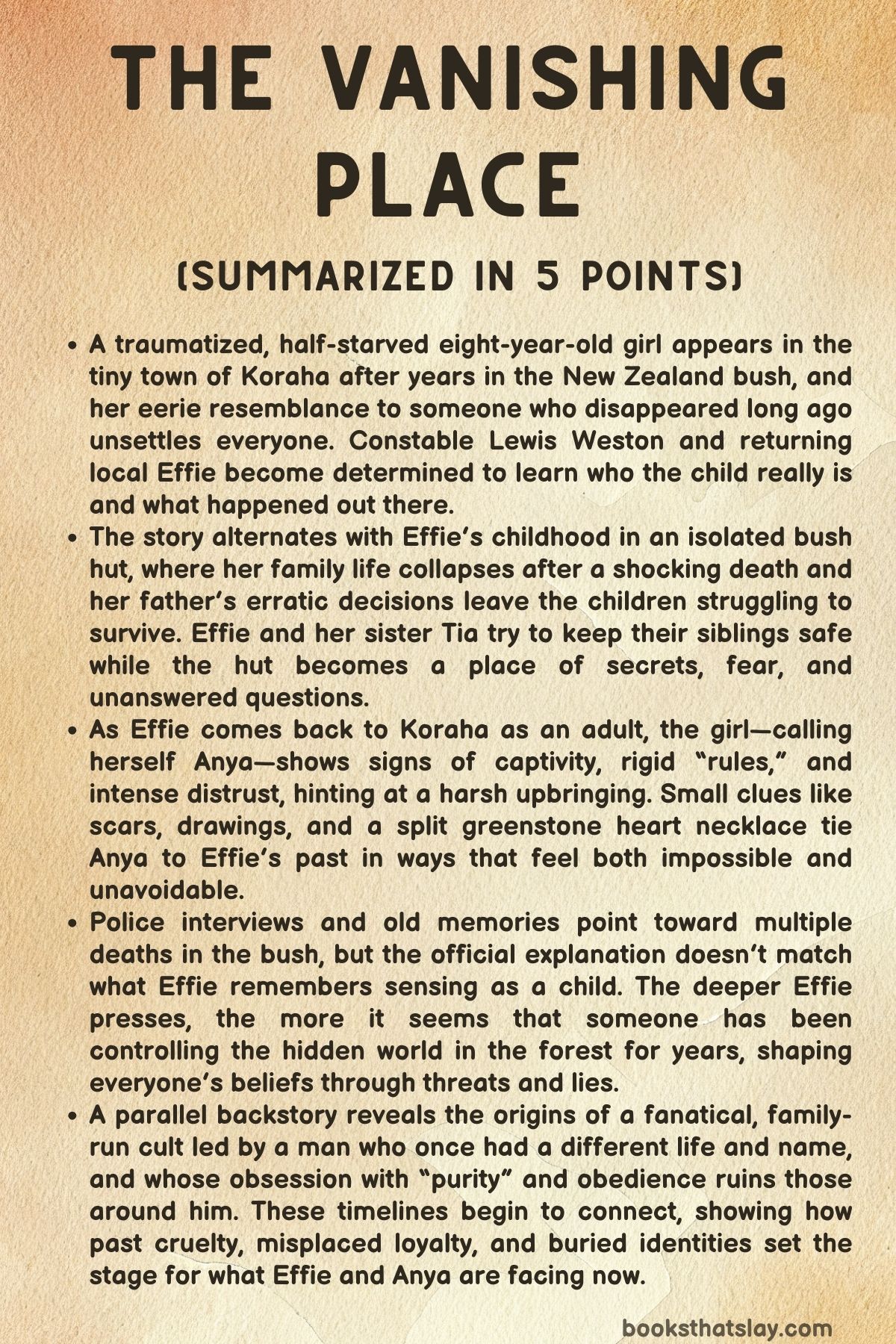

The Vanishing Place Summary, Characters and Themes

The Vanishing Place by Zoe Rankin is a dual-timeline mystery set in New Zealand’s rugged West Coast and a small town called Koraha. When a half-feral eight-year-old girl staggers out of the bush in 2025, starving and terrified, she looks uncannily like someone who disappeared nearly twenty years earlier.

Her arrival drags Effie, now an adult living overseas, back to the landscape she fled. As Effie retraces the hidden tracks of her childhood, buried family history and the shadow of a violent, isolating belief system rise to the surface, forcing her to confront what was taken, what was twisted, and what still survives.

Summary

In 2025, Koraha is jolted when a starving, exhausted girl emerges from the New Zealand bush and collapses in the town’s only grocery store. She tears into strawberries and gulps milk as if she hasn’t tasted real food in years.

The young cashier calls Constable Lewis Weston, Koraha’s lone police officer. Lewis arrives to find the child panicked and defensive, and when he gently restrains her she blurts out the name “Anya,” then refuses to say anything more.

She allows herself to be taken to the station and placed temporarily with locals, but stays silent about where she came from. Town whispers spread fast: the girl has the same face and green eyes as Effie, a child who vanished from Koraha almost two decades earlier.

Her appearance feels impossible, like time folding in on itself.

Effie is now an adult living in Scotland. When Lewis contacts her about the found girl, he doesn’t just want help identifying her.

He fears the child has come from the hut in the West Coast bush where Effie’s family once lived in secret, and he suspects Effie’s father may be involved. Effie, shaken but determined, flies home.

She drives to Koraha, where locals stare as if seeing a ghost. June, an older family friend with long white hair who once helped raise Effie, welcomes her.

Before dawn, Effie goes to the clinic and reunites with Lewis. He tells her Anya is dehydrated, covered in cuts, with old burns and marks around her ankles that suggest she has been restrained.

No missing-child report matches her, so Lewis delays involving child services, hoping there might be family who can take her in.

Anya reacts strongly to Effie, clinging to her and whispering that the adults are dangerous. She warns Effie about “rules” and threatens to flee if anyone pushes her to talk.

At June’s house she eats alone, sorts donated clothes with careful precision, and stays on edge. Lewis mentions thefts from remote huts in the Moeraki Valley and sightings of a red-haired man who could be Effie’s father.

He also wonders if Anya might be connected to Effie’s sister Tia, now long missing. Effie decides she must return to the old hut herself and find the truth.

Lewis wants to go as the investigating officer, but Effie insists she is the only one who knows the route and that a formal case hasn’t been reopened yet. June supports her, and Effie prepares for the trek.

The story threads back to 2001. Nine-year-old Effie lives with her parents, her six-year-old sister Tia, toddler brother Aiden, and a newborn brother they call Four in an isolated hut deep in the bush.

Their mother dies suddenly after giving birth, leaving Effie stunned with grief and responsibility. Their father, spiraling, disappears into a storm carrying Aiden in a pack and crossing a dangerous river without looking back.

Effie drags Tia home and tries to keep the baby alive with powdered milk spooned into his mouth. Later, the newborn vanishes from the hut.

Effie finds June outside holding him. June says their father brought her to help and will return.

Effie soon discovers her father digging a grave for their mother. She witnesses his breakdown and his insistence that they must stay hidden.

Over the next years June becomes a fragile anchor, cooking, teaching, giving the girls journals and dresses, and offering greenstone pendants that form two halves of a heart. Effie notices June keeping secrets, including a locked metal box and a photograph linked to Lewis, the local boy who once tried to help Effie.

Effie’s childhood in the bush is marked by hunger, fear, and a system of strict control built by her father’s paranoia and shame.

By 2005, Effie is twelve. One night she wakes in darkness, paralyzed, convinced she has been tied up and shut in a wooden box for angering her father.

She later learns she may have run through tree nettles that cause hallucinations and temporary paralysis, but a man named Asher, who appears around the family, hints that her father is lying. Effie clings to Aiden and Tia as her world grows more unstable.

That same year Aiden falls ill with violent seizures and breathing distress. Effie and Tia nurse him helplessly until he dies.

Their father briefly takes them into town for medical help, but soon returns, bleeding and frantic, forcing the children back into the bush. His whispered confession to June suggests he has hurt someone badly and believes escape is the only way.

Back in 2025, Anya reveals she owns the other half of Effie’s greenstone heart necklace, saying it belonged to her mother. She claims her mother was “bad” and broke someone’s rules.

During a police interview, Anya draws two dead adults: a man with a cross on his chest, identified as Four, and a woman, identified as Tia. She says Four chained her but did not hurt her, and her mother didn’t hurt her either.

She writes that her mother broke a man’s rules and wouldn’t apologize. She also names another dead figure, Hana, then shuts down.

Police search the hut and conclude Four died from tutin poisoning found in food and tea. Four’s body holds a note saying “I’m sorry,” suggesting suicide driven by guilt.

A knife bears only a child’s prints, so detectives theorize Anya poisoned Four and carved the cross into his chest. They find no trace of Tia or Hana and imply Hana may not exist.

Effie insists she sensed a man watching her in the bush, but the detectives dismiss her as traumatized. Effie refuses to accept their neat ending and continues alone.

Effie’s return to the hut becomes a trap. In the present timeline she is chained in a dark room, hearing Tia through a wall.

Tia explains that after Effie and their father left years earlier, a man named Peter arrived offering a secluded religious life. Over time he hardened into a cult leader, forcing isolation, punishing disobedience, and using threats of damnation.

His son Daniel enforced the cruelty. Tia says they killed Effie’s father when he tried to visit, then used ghost stories and an old photo to frighten Anya into obedience.

Four secretly taught Anya about the outside and marked an escape route, but Peter discovered it and poisoned Four. As Four died, he unchained Anya so she could run, and Anya carved the cross into his chest in a child’s attempt to give him peace.

Tia then reveals Peter’s real name is Adam, once known to Effie’s family as Asher. Adam is Anya’s biological father and the architect of the cult that swallowed the hut.

Adam reappears, taunting Effie and claiming Lewis abandoned Anya into foster care where she was burned. Effie doubts him, but Anya, under pressure, clings to Adam.

Daniel later drags Effie outside at gunpoint, boasting that Four’s death scene was staged to mislead police and that he assaulted Tia when she resisted. Effie sees an older, silent woman gardening: Dinah, Adam’s sister, still broken from years of captivity.

Despite her fear, Anya secretly helps Effie. She leaves a key hidden in spilled water and later sneaks Effie out at night.

They run into the forest toward a clearing where Lewis is waiting. Anya admits she lied about foster care and burns; she and Lewis made up that story to keep Adam off balance.

Daniel ambushes them and fires. Tia attacks Daniel to protect Effie and Anya.

Lewis identifies himself as police and holds Daniel at gunpoint, but a hidden shooter fires, distracting him. Lewis shoots Adam dead in the chaos, while Daniel shoots Tia.

Effie crawls to her sister, devastated, as Lewis urges escape before Daniel returns. They flee with Anya.

Three months later, Effie, Lewis, June, and Anya try to rebuild their lives. Police expect Daniel to face multiple life sentences if captured, while Adam’s remaining followers scatter.

Effie receives a letter from Cameron, revealing that Dinah is Effie’s birth mother. He explains that Dinah was taken by her father Adam years ago, and he spent decades searching.

Dinah is alive now and wants contact when Effie is ready. June confirms Dinah’s connection to Effie’s family and recalls past violence between Cameron and Adam.

The story closes with Effie holding both halves of the greenstone heart with Anya, grieving what was lost, but choosing a future that is no longer ruled by fear or secrecy.

Characters

Effie

Effie is the narrative’s emotional core, shown both as a frightened, hyper-competent child and as an adult still living inside the echo of what happened in the bush. As a nine-year-old, she is forced instantly into a parental role after her mother’s death and her father’s breakdown, and that premature responsibility shapes her entire identity: she survives by doing, organizing, feeding, cleaning, soothing, and refusing to collapse even when starving and terrified.

Her silence about trauma is not passivity but a survival strategy learned early—she compartmentalizes grief and fear because the alternative would endanger the younger children. As an adult returning to Koraha, Effie carries a complicated mix of guilt (for leaving, for surviving, for not saving Tia, for losing Four), fierce protectiveness, and a sharp instinct for danger that authorities repeatedly dismiss.

Her arc in The Vanishing Place is less about “solving” the past and more about reclaiming agency from it: she must learn to trust her own memories, accept that love and safety can coexist with pain, and stop measuring her worth by whether she can keep everyone alive. Even her attraction to Lewis is filtered through that lens—she wants connection, but the caregiver within her keeps stepping in front of her needs.

Anya

Anya arrives as a living riddle, and her character is built around the psychological reality of captivity rather than simple mystery. Her feral hunger in the grocery store is not just physical deprivation but a symbol of years of controlled, rule-bound survival; food, silence, and obedience are fused in her mind.

She oscillates between childlike tenderness and sudden, rule-enforced shutdowns, showing how captivity can make a child both hyper-vigilant and emotionally fragmented. Anya’s attachment to Effie forms fast because Effie represents a safe adult who does not demand explanations; Anya tests boundaries through threats and retreat, and Effie’s refusal to force disclosure becomes the first non-transactional care Anya has known.

Her drawings and partial statements reveal a child trained to interpret morality through someone else’s doctrine—“rules,” “bad” mothers, crosses carved for salvation—yet she also shows cunning, bravery, and moral will when she chooses escape and later helps free Effie. In The Vanishing Place, Anya embodies how trauma distorts truth: she lies when terrified, tells the truth when safe, and clings to the nearest structure of meaning until she can build her own.

Lewis Weston

Lewis is both witness and wounded participant, a man whose life has been quietly shaped by the same disappearance that shaped Effie’s. As a teenager he is tender, impulsive, and yearning for belonging, and his bond with Effie is rooted in shared loneliness and mutual rescue—each is a refuge for the other against unstable homes.

As an adult constable, Lewis tries to be the calm center of chaos, but his personal history makes him unable to treat the case as professional distance demands. His gentleness with Anya and his deference to Effie’s instincts show a man trying to correct past helplessness, to finally be useful in a story where he once could only watch.

The collapse of his marriage to Charlotte is important not for melodrama but because it illustrates his pattern: he is drawn to people marked by grief, and he attempts to build love as a shelter for pain, only to discover that pain needs its own language. Lewis’s arc in The Vanishing Place is a slow reconciliation of duty and devotion—learning that loving Effie and protecting Anya require not heroic control, but patience with uncertainty and a willingness to be vulnerable.

June

June is the novel’s quiet axis of nurture and secrecy, a woman who steps into the vacuum left by collapsed parents but whose kindness is threaded with complicity. To the children she is stability—bringing food, warmth, gifts, stories, and a sense of ritual that makes survival feel like life again.

Yet she also protects the father’s secrets, withholding truths from Effie in the name of preserving a fragile family unit, and her locked metal box becomes a symbol of the cost of that protection. June’s grief is porous: she cries alone, prays, and clings to traditions like the pounamu hearts as an attempt to keep lineage intact amid erasure.

As an adult guardian figure in 2025, she still believes in Effie’s strength to face the hut again, and she becomes a bridge between past and present. In The Vanishing Place, June represents the moral ambiguity of caretaking in isolation—she saves children, but she also helps bury history, and the story treats those two truths as inseparable.

Tia

Tia begins as Effie’s small, frightened sister and grows into a tragic figure shaped by abandonment, captivity, and coerced faith. As a child she depends utterly on Effie, mirroring Effie’s strength back to her, yet her fear and loyalty to authority also foreshadow how she might later be pulled into a controlling system.

When we meet her adult voice through the wall, Tia is battered but lucid, still protective of Anya and still capable of strategic courage. Her confession that she and the cult killed their father underscores how captivity twists moral choice: she is not framed as villainous but as someone trapped in a system where violence is normalized as obedience.

Her role in Anya’s education and escape plan reveals a stubborn maternal love surviving inside indoctrination. Tia’s death in The Vanishing Place is devastating because it comes at the precise moment she reasserts agency, showing how freedom in such systems is always won against brutal odds.

Four

Four is a child whose very name carries the eerie weight of being an “extra” life in a family already unraveling, and his character is defined by innocence caught in inherited catastrophe. As a baby he is the object of frantic caretaking, a fragile tether that forces Effie and Tia to keep moving after their mother’s death.

As a toddler he becomes a small sun in the hut, yearning for Asher and clinging to Effie, representing the possibility of joy even in deprivation. Later revelations deepen him: he grows into a quiet resistor within the cult, secretly teaching Anya about the outside world and engineering her escape.

His death, staged and then reinterpreted, becomes a battleground for meaning—suicide, murder, sacrifice, or manipulation—reflecting how power structures weaponize children’s bodies even after death. Four’s ultimate function in The Vanishing Place is as a moral compass: the story insists that even in indoctrinated isolation, a child can choose compassion over fear.

Aiden

Aiden is the youngest sibling in the early bush years, and though he has little direct voice, he matters enormously as an emblem of vulnerability and the randomness of loss. His wheezing illness and violent death shatter the fragile order Effie has built, making clear that Effie’s competence cannot outwork nature, poverty, or their father’s dysfunction.

For Effie, Aiden’s death is a turning point from “keeping everyone alive” to recognizing that survival is not justice. In The Vanishing Place, Aiden’s brief life is a reminder that the family’s tragedy is not only about human cruelty but also about the mercilessness of isolation itself.

Cameron (Effie’s father)

Effie’s father, later revealed to be Cameron, is a portrait of grief mutating into damage. At first he appears as a desperate, unstable parent—violent in confusion, fleeing responsibility, then returning in tears—suggesting a man undone by his wife’s death and by secrets he cannot share.

His decision to bury the mother, to drag children back into hiding, and to live outside society reads as both protection and control, and the children pay for his inability to process trauma without retreating into extremity. The late letter complicates him sharply: he is not simply the bush tyrant but also a man with a stolen love (Dinah), a long search, and a life warped by another patriarch’s brutality.

His remorse toward Anya and promise not to fail “the next one” position him as someone who recognizes the generational pattern even if he could not break it in time. Cameron in The Vanishing Place embodies cyclical harm: a father who loves fiercely, fails catastrophically, and is still human enough to grieve what those failures cost.

Adam / Asher / Peter

Adam, who moves through the story under multiple identities, is the clearest manifestation of inherited fanaticism and the seductive mechanics of control. His childhood scene shows a boy trained to equate obedience with righteousness, and his “help” to Dinah is already corrupted by his father’s doctrine: care becomes surveillance, purity becomes punishment, and love is always conditional on submission.

As Asher he enters Effie’s world like a soft-spoken ally, suggesting how predators often present safety before tightening cages, and his disappearance after whispering truth to Effie hints at his double life taking form. As Peter, cult leader and Anya’s biological father, he becomes the full flowering of that inheritance—rewriting God into a tool of domination, isolating a community to make his authority absolute, and using fear, ritual, and punishment to keep victims compliant.

His taunting of Effie in captivity is not random cruelty but ideology: he needs her repentance because her freedom threatens the story he tells himself. In The Vanishing Place, Adam is not a monster dropped from nowhere; he is what patriarchy, fanaticism, and unchallenged violence can grow in a child when no other moral world is offered.

Daniel

Daniel is the heir and enforcer of the cult’s violence, shaped to convert doctrine into action. His cruelty toward Tia and Effie is performative as well as sadistic: he boasts, humiliates, and “stages” deaths because power for him is theater.

Yet he is also a product of his father’s system, raised to believe that dominance is holiness and that harming others confirms his standing. His gunpoint “exercise” of Effie shows how he calls brutality “discipline,” and his escape instinct when challenged reveals cowardice beneath the swagger.

Daniel’s role in The Vanishing Place is to show how authoritarian belief reproduces itself not only through leaders but through sons who learn to enjoy the leash they were born holding.

Dinah

Dinah is the story’s long-silenced heart: a girl crushed by her father’s religious tyranny and then forced into obedient emptiness. Her teenage pregnancy and desperate labor scene make her vivid as a person with agency and fear, but her later imprisonment shows how systematically that agency is erased—her silence is not consent but the residue of years of breaking.

In the present she appears as an older woman gardening quietly, a haunting image of survival without liberation. Yet her existence also reframes Effie’s lineage, turning the family story into one of stolen motherhood, interrupted love, and survival across generations.

Dinah in The Vanishing Place represents what captivity can do to identity, and also how truth can persist even when a voice is stolen.

Blair

Blair functions as Effie’s outside-world anchor and psychological interpreter. As Effie’s friend and a doctor, Blair offers the language Effie lacks for what Anya is experiencing, connecting captivity trauma to recognizable patterns and modeling a compassionate, non-sensational way to respond.

She is important because she does not romanticize Effie’s strength; she names its cost and gives Effie permission to be unsure, tired, and human. In The Vanishing Place, Blair embodies the healing potential of friendship that is steady, practical, and unafraid of hard truths.

Charlotte

Charlotte is less a central actor than a revealing mirror for Lewis. Her shared earthquake grief with Lewis creates a marriage that is initially built as mutual refuge, but the later unraveling shows what happens when trauma becomes the only glue in a relationship.

Through her, the novel highlights that survival bonds are not the same as chosen compatibility, and that grief can exhaust love if it is never metabolized. Charlotte’s presence in The Vanishing Place deepens Lewis’s character by exposing his longing to repair hurt through partnership.

Detectives Morrow and Wilson

Morrow and Wilson represent institutional logic colliding with lived trauma. Their interviews are professional and, at moments, careful, but they are also quick to reduce a labyrinthine human story into the cleanest narrative that evidence seems to allow.

By focusing on a child’s fingerprints and a convenient suicide note, they reenact the novel’s theme of disappearance in another form—truth vanishing under the pressure for closure. In The Vanishing Place, they are not cartoon antagonists; they are a reminder that systems built for clarity often fail people whose lives were engineered to be unclear.

Constable Griffiths

Constable Griffiths appears briefly but plays a crucial symbolic role as a rare adult who intervenes when a child is being harmed. His stopping of Lewis’s father contrasts with the many adults who look away in both timelines, and his presence helps explain why Lewis grows into a policeman who tries to act where others hesitated.

In The Vanishing Place, Griffiths is a flicker of what responsible authority can look like.

Lily

Lily, revealed as Effie’s grandmother and Dinah’s mother, is a late-arriving but load-bearing figure in the family’s hidden history. Through June’s recollections, Lily’s friendship and losses show that the roots of the tragedy stretch beyond one generation, and that the women in this lineage repeatedly tried to protect each other against a violent patriarchal force.

Lily in The Vanishing Place stands for the buried matrilineal story that the cult and the bush secrecy tried to erase, but could not.

Themes

Trauma, Memory, and the Body as Evidence

Effie’s life is shaped by events that her mind can’t hold cleanly, so her body carries what language fails to. The story repeatedly shows trauma not as a single wound but as a long condition that changes perception, trust, and even time.

When a starving child staggers into Koraha and cannot say who she is, that silence isn’t emptiness; it is a survival strategy built from terror and conditioning. Effie’s childhood memories are fragmented, arriving as sensations—storms, the smell of blood, nettle burns, the weight of a baby, the rasp of a chain—rather than orderly recollections.

That fragmentation becomes a key to understanding how deeply violence has altered her inner world. Her adult self does not return to New Zealand as a neutral investigator; she returns as someone whose past still lives in muscle memory and adrenaline spikes.

This is why she senses danger in the bush even when police dismiss her as unreliable. The novel also makes trauma contagious across generations.

Anya’s fear of “rules,” her reflex to shut down under questioning, and her confusion about what is normal all echo patterns Effie learned as a child. In The Vanishing Place, pain is not only recalled but reenacted through panic, avoidance, hyper-vigilance, and sudden attachment.

Importantly, the book doesn’t romanticize recovery. Effie can soothe Anya for a night, but she cannot remove the nightmares or the learned dread of adults.

The narrative makes clear that trauma is stored in the nervous system: hunger triggers flashbacks, locked doors trigger disaster, and a necklace triggers recognition of a lineage of suffering. Even small details—ligature marks on Anya’s ankles, old scars, Four’s carved cross—work like physical footnotes to a story that has been forced underground.

The theme insists that truth is not only a matter of testimony; it is also written on skin, posture, and instinct. Healing, then, is not a simple decision but a slow re-training of reality, where safety must be proven again and again before it can be believed.

Control, Captivity, and the Corruption of Faith

The cult at the center of the story shows how domination can disguise itself as moral order. The leader’s authority is not maintained only through locks and chains but through a theology that turns fear into obedience.

Rules are presented as holy, punishment as correction, and isolation as purity. This warps the victim’s sense of choice: when Anya says adults are bad and can’t be trusted, she is repeating the logic of captivity where the outside world is framed as sinful and dangerous.

The book traces this pattern back decades. Adam’s childhood memory of Dinah’s labor and their father’s violence reveals the origin of his obsession with control.

His father polices women’s bodies, sexuality, and movement as if they are threats to the family’s salvation; Adam learns that love equals enforcement, and enforcement equals righteousness. Later, as Peter, he recreates the same structure with new victims.

The Vanishing Place shows that captivity is most effective when it recruits the captive into believing in it. Dinah’s silent gardening in 2025 is one of the clearest images of this: a person still alive, still moving, but hollowed out into compliance.

Tia’s years in the bush also show the slow tightening of control—what begins as a “secluded faith-based life” becomes a closed system where dissent is treated as sin and where even motherhood is governed by a man’s rules. The theme is not merely about an “evil cult,” but about the mechanics of coercion.

The leader rewrites history, uses ghost stories and photos as psychological traps, and manipulates children into loyalty by mixing affection with terror. Violence is not random; it is ritualized as discipline.

Even Four’s death is arranged to look like guilt and suicide, because control extends to narrative itself. Faith is not condemned as a whole; rather, the book isolates a specific corruption of faith into a weapon.

The story asks how easily spiritual language becomes a tool for people who want power, and how hard it is for survivors to untangle God from the hands that hurt them.

Family, Inheritance, and the Unchosen Bonds That Shape Identity

Family in the novel is both shelter and trap, and the characters aren’t free to choose which version they inherit. Effie grows up in a hut where care is real—she feeds babies, holds Tia’s hand, comforts Four—yet that same family context contains a father who disappears, lies, and subjects the children to a life of constant danger.

The result is a complicated loyalty: Effie can mourn her father and also fear him. The theme becomes even more layered when the story reveals hidden parentage and long-buried connections.

The late revelation that Dinah is Effie’s birth mother reframes Effie’s sense of self. Her life has been shaped by a lineage of captivity she did not know she carried.

That knowledge is not offered as a tidy closure; it is another shock that forces her to re-map her origins. The Vanishing Place treats inheritance as emotional and psychological, not only genetic.

Adam inherits his father’s cruelty and religious paranoia and then reproduces it on others. Effie inherits her mother’s endurance and June’s steadiness, but also the family’s habits of secrecy and silence.

Anya inherits not only trauma but also the green pounamu heart, a symbol that binds women across generations even when bloodlines are broken or stolen. The necklace matters because it resists the cult’s attempt to erase kinship; it carries memory that the captor cannot fully control.

The story also explores chosen family as a counterforce. June is not Effie’s mother by blood, but she mothers through labor, food, and protection.

Lewis is not family by structure, yet he becomes one of the few safe constants in Effie’s life. Anya’s bond with Effie forms quickly and intensely because it fills a hole left by betrayal and loss.

The theme suggests that family is not a simple moral category. It can be the source of belonging and the machinery of harm at the same time.

Identity, therefore, becomes a negotiation between what was imposed—names, rules, disappearances—and what is reclaimed through truth and relationship.

Silence, Storytelling, and the Fight Over What Counts as Truth

Much of the novel’s tension comes from who is allowed to speak and whose version of events is believed. The child who arrives in Koraha is dismissed by institutional procedures that want clear timelines, neat motives, and readable evidence.

Anya’s silence in interviews is interpreted as suspicion rather than injury; her drawings are treated like clues only when they fit the police theory. Effie’s instincts are brushed aside as trauma, a way of discrediting lived experience because it does not conform to official logic.

The Vanishing Place keeps returning to the mismatch between personal truth and public proof. Four’s note, the knife with child prints, and the absence of Tia’s body are used to build a narrative that makes the case “solved,” even though Effie recognizes the holes.

The theme shows that silence is often produced by power. Dinah is silenced by chains and shame.

Tia is silenced by years of threats. Anya is silenced by fear of punishment and by the learned belief that speaking causes suffering.

Yet silence can also be tactical. Effie withholds her full plans from the police because she knows the terrain and understands that the system’s caution might cost lives.

The book treats storytelling as survival: Four marks a route for Anya; Anya leaves clues through drawings and half-truths; Effie follows the trail of memories she once tried to bury. Competing stories battle for dominance—Adam’s story that the outside world is evil, police stories that reduce complex crimes to single culprits, June’s careful half-stories meant to protect children, and survivors’ stories that emerge slowly, with contradictions and pauses.

The theme does not argue that truth is relative; it argues that truth often needs the right conditions to be spoken and heard. By the end, the most reliable map of reality is not an official report but the fragile, pieced-together testimony of those who were forced to live it.

Survival, Moral Ambiguity, and the Cost of Staying Alive

Survival in the novel is never clean or heroic; it is messy, exhausting, and morally complicated. Effie survives childhood by becoming an adult far too early, feeding babies with teaspoons, burying grief to keep moving, and adopting denial when reality would otherwise break her.

Her father’s actions sit in this ambiguity too. He is capable of tenderness and also of choices that endanger or abandon his children.

The book refuses to flatten him into a single role; instead, it shows how terror and guilt can twist a person into both protector and threat. Anya’s survival is even more ethically tangled.

She carves a cross into Four’s chest not from cruelty but from a child’s logic shaped by religion and fear. She lies in interviews, not to mislead for sport, but because speaking truth once carried lethal consequences.

The police misread these acts because they expect survival to look innocent. The Vanishing Place insists that in extreme conditions, children learn to do what works, even if it horrifies outsiders later.

The theme also highlights how survival can include attachment to the abuser. Anya can cling to Adam and still want to escape, because the person who hurts you can also be the person who controls your food, your sleep, your rules of reality.

Effie’s urge to return to the hut alone is another survival reflex: she trusts herself more than any institution, because self-reliance once meant life. Even love is shaped by survival.

Effie and Lewis feel drawn to each other, but their capacity to act on that is throttled by responsibility, distrust, and the urgency of rescue. The story shows that staying alive often demands trade-offs: secrecy over honesty, speed over safety, suspicion over openness.

And when survivors finally reach a safer world, the cost remains visible—nightmares, guilt, anger, and the hard work of building a life that isn’t organized around running. Survival is presented not as the end of the story but as the beginning of another struggle: learning how to live when danger is no longer the main rule.