The Wilderness Summary, Characters and Themes

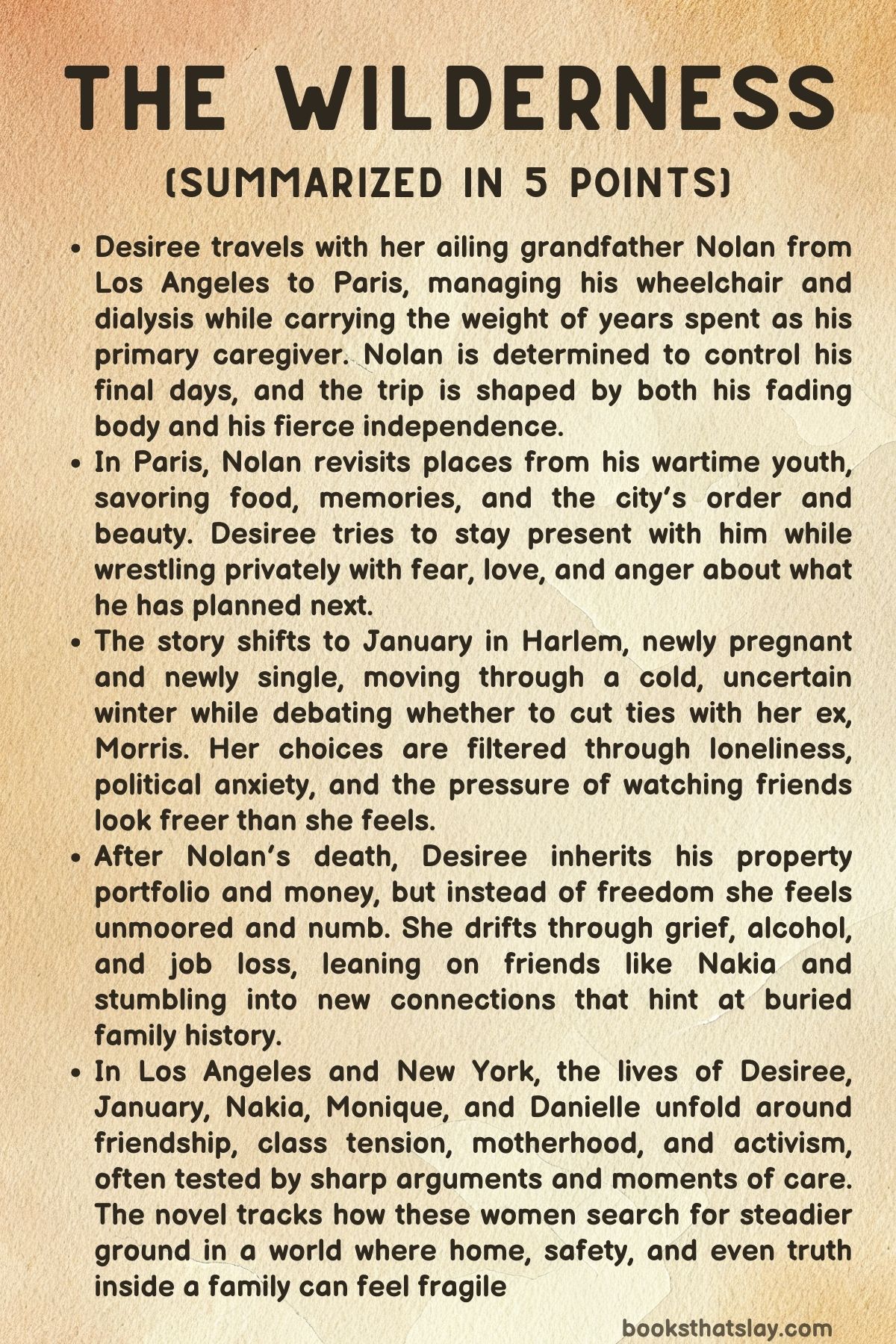

The Wilderness by Angela Flournoy is a multi-voiced, near-future novel about friendship, family, and the pressure of living through social collapse. Centered on Desiree and her tight circle of Black women, the story moves between Los Angeles, New York, and Europe as the characters face illness, inheritance, marriage, motherhood, ambition, and activism.

Their private lives unfold alongside widening public crises: housing battles, climate stress, political unrest, and the growing violence aimed at unhoused people. Flournoy presents a world that feels only a step ahead of our own, asking what community can survive, what it must forgive, and what it costs to keep choosing one another.

Summary

Desiree boards a red-eye from Los Angeles to Paris with her grandfather Nolan, who is in the late stages of diabetes and kidney failure. He is frail, uses a wheelchair, and needs portable dialysis.

Desiree has spent years caring for him: giving insulin, helping him dress, watching his body deteriorate through amputations and infections. Their bond is intimate but tense, shaped by his pride and her exhaustion.

On the plane she listens to his ragged breathing and thinks about how home became a place defined by medical routines and quiet resentment.

At Charles de Gaulle, an airport worker helps them to a small hotel. Nolan is unusually alert, carrying maps and documents.

Desiree understands why. The Paris trip is not the destination but a soft landing before Zurich, where Nolan has arranged assisted death.

He has paid a Swiss organization to evaluate him, confirm his terminal condition, and administer a lethal injection. He refuses to keep living through more surgeries, dependency, and humiliation.

Desiree is torn between love, fear, and anger, but she comes because she will not abandon him.

In Paris, Nolan seems revived by memory. He jokes with the receptionist and recalls being stationed there during World War II, driving supply trucks and courting French women in the same streets.

Back in their room, as dialysis runs, he sends Desiree out to find foods he wants for his “last meals. ” She returns with whatever she can, full of worry as he eats sweets and fried food that could worsen his condition, while he insists on pleasure over prudence.

They spend the day in the Tuileries Garden, where Nolan orchestrates a little lesson in symmetry, having Desiree stand between fountains to see the aligned monuments. Later they ride in an accessible van through the city, passing landmarks that feel half like sightseeing and half like farewell.

In Montparnasse, Nolan asks to stop near a building with a red door. He stares at it with wet eyes, then chooses not to go inside.

Desiree senses a story he will not tell.

Back at the hotel, their conflict sharpens. Desiree wants him to tell her sister Danielle about Zurich.

Nolan resists; Desiree calls anyway. Danielle, in Cleveland, is shocked and suspicious, wondering if Nolan is confused or incapacitated.

Desiree argues that he is clear-headed and has planned everything himself. Danielle warns that Desiree will have to live with what happens and hangs up, leaving Desiree isolated with the decision.

At dinner Nolan drinks Bordeaux and eats steak with gusto. He offers to travel alone to Zurich so Desiree won’t feel responsible, but she refuses.

He then hints that Desiree’s mother Sherelle might not have been his only child, telling a veiled story about a soldier who left a baby behind in France. He will not explain further, deepening the sense of secrets he is carrying to the end.

That night he asks for another drive and returns to the red door, letting Desiree knock while he stays back. He still refuses to enter; he only wants to sit near his past.

The next morning they take the train to Zurich in steady cold rain. Desiree falls asleep and dreams of childhood with her mother and sister.

She wakes to a ticket inspector and sees Nolan collapsed, his mouth flecked and body slack. He has died in his seat before reaching the appointment.

Desiree is left with grief and an eerie relief that choice was taken out of her hands.

In 2018 in Harlem, January Wells lives alone in a freezing studio after separating from her partner Morris. She is newly pregnant, anxious about the country’s direction, and stung by friends posting vacation photos.

She steps into an upstairs apartment just vacated by eviction, pockets a sepia photo left behind, and sees the former tenants’ belongings piled on the curb. In a coffee shop, she drafts a letter to Morris: she will keep the baby but wants him to relinquish parental rights.

A loud businessman triggers her anger, then her first intense bout of morning sickness. She vomits, admits her pregnancy to the stranger, and later video-calls Desiree, who urges her to wait before sending the letter.

January insists she wants distance from Morris and walks home through marches and pink hats, laughing at a Harriet Tubman statue adorned with one. The moment is absurd and clarifying: she realizes she has time to decide.

After Nolan’s death, Desiree feels Los Angeles is unbearable without family. She travels to Zurich for his cremation, then rides trains through the Alps scattering small portions of his ashes in villages he would have liked.

Returning to Leimert Park, she finds no comfort from Danielle, who remains estranged. In Nolan’s estate she discovers multiple shabby rental properties.

Tenants show her neglected repairs, and she sees a side of Nolan she never knew: careless, even exploitative. She sells everything except the Leimert Park house, collects insurance payouts, and ends up with nearly a million dollars.

The inheritance feels heavy rather than freeing. She drinks too much, loses her restaurant job, and drifts through days with reality TV and numbness until a friend’s cousin advises her to invest most of the money and buy herself time to heal.

A year later, Desiree marks her return to New York by booking bottle service at a Harlem club with her friends Nakia, January, and Monique. January arrives with Morris and his friends Dale and Chika.

Chika, a new doctor, says Desiree looks familiar. The night turns sour when Nakia reports that Dale grabbed her chest without consent.

The friends leave together, shaken. In the taxi, Nakia admits she feels out of place in New York and is thinking of moving back to Los Angeles.

Desiree tries to stay calm but fears losing the one person who feels like family.

Later, Desiree notices Chika has accepted her friend request. Scrolling his photos, she spots a 2008 Haiti medical-training group shot with Danielle in it.

She realizes Chika and Danielle once worked together. Curious and unsettled, she goes to meet him.

The novel broadens into other lives and years. Monique’s public voice grows through essays and a viral talk about history, power, and institutional comfort.

Nakia returns to Los Angeles, builds Safe House Café, and navigates love and loyalty among her staff and partners. She and her partner Jay host political dinner parties where friends debate water scarcity, housing, protest language, and the cruelty aimed at unhoused people.

A small earthquake interrupts an argument about fame and purpose, exposing how fragile their certainty has become.

The story revisits January’s later marriage to Morris and the exhaustion of motherhood. After her second child Brook is born, she slips into a brutal postpartum period marked by nausea, sleeplessness, and isolation in a new suburban house.

Desiree flies to check on her, alarmed by how much January is carrying alone.

Danielle, now in Washington, D. C.

, meets her estranged father Terry in Central Park. He claims Sherelle pushed him away and says he paid support that Nolan may have hidden.

Danielle leaves furious and disoriented. On the train home she calls Nakia, hoping for a bridge back to Desiree.

Jay answers instead, panicked, and tells her Nakia is dead.

Desiree is wrecked by the loss. Nakia was her true anchor, the person who made life feel survivable.

Media reduce Nakia to a headline, and Desiree helps Jay and Nakia’s parents sort through the home, watching meals Nakia prepared rot in the fridge like a calendar of absence.

A later section shows what led to Nakia’s death in 2027 Los Angeles. During the Bunker Hill Uprisings, police violence against unhoused residents sparks massive protests and a harsh curfew.

Nakia joins friends to distribute food downtown. Police robo-trucks trap crowds on the Sixth Street Bridge.

A National Guard helicopter dumps thousands of gallons of water on the kettled protesters, then rubber bullets follow. Nakia is hit, the freezing crowd panics, and people run.

In the chaos, some are crushed and Nakia is fatally harmed.

In the present, Nakia’s neglected garden becomes a symbol of what still might live. Desiree returns to the house with loved ones, ready to restore the garden and, with it, the bonds among the survivors.

The novel closes on that tentative rebuilding: grief still raw, society still unstable, but friendship and family stubbornly chosen again.

Characters

Desiree

Desiree functions as the emotional anchor of The Wilderness, a woman shaped by caretaking, loss, and the long echo of family fracture. Her life has been narrowed for years by responsibility to Nolan, and that narrowing leaves her both deeply competent in crisis and painfully unsure of who she is without someone to save.

In Paris and on the way to Zurich, her love for Nolan is mixed with exhaustion and resentment, not because she wants him to suffer but because she has already been living his slow death beside him; the trip forces her to face how little control she truly has over the people she loves. After Nolan dies, Desiree’s inheritance becomes a moral weight rather than a gift, exposing her discomfort with the ways love, care, and property can coexist with harm.

Her heavy drinking, job loss, and drifting in New York aren’t just grief behaviors; they reveal how thoroughly her identity had fused with being needed. Desiree’s friendships, especially with Nakia and January, become her substitute family, and each time that family threatens to shift or collapse, she reacts with the terror of someone who has already been abandoned too many times.

Her later confrontation with public cruelty toward unhoused people shows that her compassion is not abstract: she steps in, even when it costs her safety and stability. By the end, Desiree is a figure of survival who keeps trying to rebuild kinship from wreckage, stubbornly believing that tending what remains—like Nakia’s garden—can still be a form of love.

Nolan

Nolan is a study in pride, vulnerability, and the complicated authority of elders in The Wilderness. His diabetes and kidney failure strip away physical autonomy, yet he clings to emotional and moral control, refusing help even while relying on Desiree for everything.

In Paris, his alertness and flirtatious charm remind Desiree—and the reader—that he is more than his decline; he is a man still capable of performance, memory, and choice. His decision to pursue assisted suicide is rooted as much in fear of humiliation as in pain: he wants to die while still feeling like himself, before helplessness rewrites his identity.

Still, his control has sharp edges; he needles Desiree, weaponizes jokes, and uses his looming death to command the room. The hint that he may have fathered another child speaks to a life that held secrets Desiree never fully understood, reinforcing how parents and grandparents can remain partly unknowable no matter how close the care relationship becomes.

Nolan’s failings also surface posthumously through his careless landlord history, complicating any simple reverence for him. He loved his granddaughters, but he also constructed narratives that centered himself as their sole protector, possibly hiding Terry’s support to preserve that role.

Nolan’s death on the train—before the planned ending—becomes his final contradiction: even in seeking control over death, he is still subject to the body’s timing, leaving Desiree with both grief and the burden of unfinished answers.

Danielle Joyner

Danielle is a portrait of guarded strength and unresolved rage in The Wilderness. Living in Washington, D.C. and operating as a successful adult does not soften the wound of her upbringing; instead, it hardens into a strict moral framework that keeps her safe but isolated.

Her estrangement from Desiree reflects how grief can ferment into accusation—someone must be to blame for the past, and proximity makes Desiree an easier target than the dead. When Danielle meets Terry, her fury is not performative; it is the fury of a child who grew up without a father and without the resources that might have made Nolan’s hardship more bearable.

Terry’s claim that he paid support and that Nolan may have hidden it destabilizes Danielle’s internal story, but it does not heal her, because the neglect she felt was not only financial—it was relational. Danielle’s reflection afterward that Sherelle’s absence matters more than Terry’s shows her capacity for emotional honesty, suggesting that beneath her anger is a profound yearning for maternal grounding that never returned after Sherelle died.

Her tentative impulse to call Nakia reveals that she is not closed off by nature; she is cautious because every attempt at closeness risks reopening old injuries. The phone call that ends with Nakia’s death announcement is a brutal irony, positioning Danielle again at the edge of family catastrophe, trying to step toward reconciliation only to have loss widen the distance.

January Wells

January embodies the tension between autonomy and vulnerability in The Wilderness, especially as motherhood collides with political and personal instability. When we meet her in Harlem, she is newly pregnant, newly separated, and overwhelmed by a sense that the world is tipping into something uglier; her decision to ask Morris to relinquish parental rights is both a bid for freedom and a symptom of fear that she cannot rely on anyone.

Social media envy and the eviction scene she walks into underline her sensitivity to structural precarity—she sees how easily stability can vanish, and she doesn’t trust her own foothold. Her confrontation with the loud man at the coffee shop, and the nausea it triggers, capture her rawness: she is brave, but her body and mind are already under strain.

Later, in 2019, January’s postpartum collapse in the Inland Empire McMansion reveals the cost of carrying everything alone. Breastfeeding-induced nausea, sleeplessness, and emotional numbness show a woman drowning in the expectation to be endlessly capable.

She loves her children fiercely, yet she is trapped in a domestic architecture designed to look successful while hiding how isolating it is. The cryptic text—“Two things can be true at the same time”—signals her attempt to make peace with paradox: she can love motherhood and still feel erased by it; she can be grateful for a home and still feel imprisoned there.

January’s arc insists that self-determination is never a clean victory; it is a daily negotiation against exhaustion, fear, and the invisible labor of being the default parent.

Nakia

Nakia is the heartbeat of community in The Wilderness, someone who builds belonging through food, debate, and fierce loyalty. As Desiree’s closest friend, she becomes the chosen-family figure who steadies others even while quietly questioning where she fits.

Her restaurant life—especially Safe House Café—shows her as a caretaker on a larger scale, feeding neighborhoods, mentoring staff, and holding space for people’s hunger in every sense. Yet her personal life is restless: she drifts between New York and Los Angeles, between relationships and identities, testing futures without committing easily because commitment has consequences.

At the Group of 7 dinner party, Nakia is intellectually alive and politically engaged; she is not just hospitable but rigorous, someone who believes ideas matter because bodies will bear their outcomes. Her discomfort when Monique suggests the housed will harm the unhoused exposes a fault line in her ideals: Nakia wants to believe in solidarity, yet she is forced to confront how proximity to comfort can blur moral clarity.

Her love life also reflects her complexity—her partnership with Jay contains tenderness and ideological alignment, but her secret relationship with Reina suggests a part of her that resists being fully known or fully settled. Nakia’s death during the Bunker Hill Uprisings is a devastating culmination of her values: she dies while serving and resisting, not because she sought martyrdom but because the world she fought for turned violently on the vulnerable.

The neglected garden and Desiree’s later return to restore it symbolize Nakia’s enduring role as a cultivator—of plants, of people, of hope—even after her life is cut short.

Monique

Monique operates as The Wilderness’s conscience and provocateur, a character who refuses comfort in easy narratives. Her viral public talk and blog presence make her a public intellectual figure, but her internal life is more fraught: she is drawn toward visibility while fearing what visibility might hollow out.

Her older essay about the slave cabins committee shows her acute awareness of institutional dishonesty and her own complicity inside it; she is neither naïve nor self-exonerating. At the Group of 7 dinner, Monique pushes the conversation past polite radicalism into fearsome possibility, insisting that cruelty toward unhoused people is not hypothetical but structurally incubated.

This insistence unsettles Nakia because Monique doesn’t allow “good intentions” to stand in for outcomes. Yet Monique is not invulnerable; her terror during the earthquake and her later anger reveal that her sharpness is partly armor.

She wants community, as her toast shows, but she also wants to be heard on her own terms, and when Nakia challenges her ambition, it hits a bruised place. Monique’s character illustrates how activism, fame, and friendship can strain one another, especially when everyone is grieving different versions of the future.

Jay

Jay is a stabilizing but quietly complicated presence in The Wilderness, representing the intersection of idealism and privilege. Her condo, her boards, and her post-tech wealth place her in a materially secure world, yet she tries to channel that security into collective good through green HR consulting and community initiatives.

At the Group of 7 dinner, Jay’s role is both host and intellectual participant; she challenges simplistic solutions like desalination while still holding space for debate. Her toast after Monique’s provocation reflects a desire to keep community intact when tension rises, showing her instinct to mend rather than fracture.

Still, Jay’s sense of leadership has limits; she can encourage Monique’s public platform and praise “the world needing her story,” but this also hints at how she may romanticize activism from a safer perch. The phone call with Danielle after Nakia dies reveals Jay’s raw, panicked grief and the sudden collapse of a life she was building beside Nakia.

Jay is a portrait of someone trying to live ethically within advantage, and learning in real time how fragile those ethical architectures are when violence breaks through.

Morris

Morris is less a villain than a catalyst in The Wilderness, embodying the tension in shared parenthood and the gendered expectations around care. January’s desire to detach from him early in her pregnancy implies a relationship where support felt unreliable or entangling.

His presence at the Harlem club night, surrounded by friends, suggests a social ease that contrasts with January’s isolation. Later, in Los Angeles, his return from work while June manages Bronze shows the household’s default structure: Morris is a parent, but not the one whose body and mind are being consumed daily by childcare.

He may not be cruel, but the narrative positions him as part of the machinery that makes January feel alone. His character highlights how ordinary imbalance can become devastating under postpartum strain, not because one partner intends harm but because the system rewards their absence.

Chika

Chika enters The Wilderness as a spark of possibility and unease. New to New York after residency, he seems open, generous, and intuitively drawn to Desiree, sensing familiarity even before she does.

His Haitian medical mission photo places him in a world of global service and professional ambition, but the real narrative weight of Chika is relational: he becomes a living bridge to Danielle’s past. For Desiree, he represents both temptation and a chance to unearth family secrets—someone who has seen Danielle in a different role, perhaps with a softer face than Desiree knows now.

Chika’s gentle disappointment when she leaves the club and his invitation to meet suggest a man used to directness and connection, making him a subtle foil to Desiree’s guarded grief. Even with limited page time, he functions as a hinge character: he opens a door toward reconciliation or revelation, whether Desiree wants that door open or not.

Dale

Dale is a brief but telling figure in The Wilderness, illustrating how menace can enter social spaces under the guise of friendliness. His sudden grabbing of Nakia’s chest at the club isn’t treated as a misunderstanding; it is a violation that exposes the vulnerability women carry even in celebratory settings.

Dale matters less as an individual than as a reminder of how quickly safety can collapse, and how such moments ripple through friendships, forcing Desiree and the others to navigate care, belief, and rage in real time.

Brandyn

Brandyn appears as a mirror to Nakia’s sense of displacement in The Wilderness. Their relationship sits inside a New York artsy world that Nakia experiences as alienating, suggesting a mismatch not just of personalities but of cultural comfort.

Brandyn’s presence helps clarify Nakia’s longing for Los Angeles and for a community where she doesn’t have to translate herself. More than a partner, Brandyn symbolizes a life Nakia tried on and found constricting.

Rico

Rico is part of the Group of 7 ecosystem in The Wilderness, representing engaged urban politics and the friction of discourse-driven friendship. His claim about the origin of “NIMBY” and his protest participation show him as historically aware and active, someone who locates personal life inside structural struggle.

Rico’s character helps frame the dinner parties as spaces where intellect and intimacy overlap, and where political identity is a shared language of bonding.

Kyle

Kyle functions in The Wilderness as a portrait of care constrained by realism. Their choice to stay home with a baby during the 2020 protests doesn’t read as apathy; it reads as the compromise many parents make between ideals and obligations.

Kyle’s contributions to debate, alongside parenting responsibility, show how activism can take quieter forms, and how community includes people at different intensities of public action.

Beverly

Beverly is the oldest and most cautious member of the Group of 7 in The Wilderness, embodying generational tension around property and civic identity. Her initial defensiveness about homeowners being “looked down on” reveals a lifetime of values built around ownership as stability.

Yet she is not rigidly closed; she listens, adjusts, and eventually aligns with calling the protests rebellions, suggesting an ability to evolve when treated as part of the conversation rather than an enemy. Her later drunken monologue about corporations dying like people is darkly comic but also philosophical, revealing a mind that processes history through the rise-and-fall cycles of institutions.

Beverly offers the group—and the reader—a reminder that political learning can happen late, and that discomfort doesn’t automatically mean opposition.

Yesenia

Yesenia brings pragmatic institutional knowledge into The Wilderness through her city hall job and policy-forward thinking. Her push for desalination reflects belief in technical solutions and state capacity, while her willingness to debate shows she is not a bureaucrat hiding behind procedure.

Yesenia’s protest participation indicates she straddles inside and outside roles in governance, suggesting the tension of working within systems you also critique. She rounds out the Group of 7 as someone who wants results, even when the path is contested.

Sherelle

Though absent in the present, Sherelle’s shadow shapes The Wilderness profoundly. As Desiree and Danielle’s mother, her death is described as the central vacancy of their lives, a loss that reorganized everything afterward.

The sisters’ memories of childhood softness in dreams contrast with the hard adolescence under Nolan, implying Sherelle represented warmth, protection, and emotional coherence. Sherelle’s removal from the family story also intensifies the mystery of lineage—Nolan’s hint about another child makes her absence feel like a missing chapter that might contain truths neither granddaughter fully knows.

Terry Joyner

Terry is a complicated embodiment of abandonment and contested truth in The Wilderness. His meeting with Danielle is not a plea for forgiveness so much as a demand to be understood, and his version of the past—dangerous marriage, pushed out, child support paid—collides head-on with Danielle’s lived experience.

Terry’s claim that Nolan hid payments introduces the possibility that the family’s foundational narrative was shaped by Nolan’s desire to be indispensable. Yet Terry’s accountability remains partial; he admits he could have tried harder but frames helplessness as inevitability.

His offer to introduce Danielle to his teenage son and his request for Desiree’s contact show genuine desire to reconnect, but they come after decades of silence, when the emotional cost is already entrenched. Terry’s character forces the book to ask whether explanation can ever arrive in time to matter.

Warren

Warren, Danielle’s husband, is a quiet stabilizer in The Wilderness. Though he appears briefly, his role matters as a point of return: Danielle texts him after her painful meeting, and he is the person she rushes home to when disaster strikes.

Warren represents the life Danielle has painstakingly built to counteract childhood instability, yet his sleepy presence when she arrives with news underscores how sudden catastrophe can pierce even the most carefully constructed safety.

Ade

Ade’s small role in The Wilderness nevertheless underscores the theme of human kindness amid decline. As the airport worker who helps Nolan, he is a fleeting caretaker in a story crowded with caretaking, reminding Desiree that help can come from strangers even when family feels thin or hostile.

His presence also reflects the quiet dignity Nolan still inspires in others, even as his body fails.

Octavia

Octavia, the unhoused woman assaulted by the ice-cream truck driver, symbolizes the moral battleground of The Wilderness. She is not given a long arc, but her vulnerability and near-erasure in the viral video reveal the culture the book fears: a world where the unhoused become props for outrage rather than people.

Octavia’s name also connects to Monique’s Octavia Butler reference, turning theory into flesh and forcing Desiree’s ethics into action.

Arielle and L.

Arielle and L. appear during the Bunker Hill Uprisings as Nakia’s companions in direct aid work.

In The Wilderness, they represent the kind of mutual-aid community Nakia trusted—friends who respond to crisis with food, presence, and risk. Their shared experience on the bridge situates Nakia’s death inside a collective struggle rather than a solitary tragedy.

Juanita and Conrad

Juanita and Conrad, Nakia’s parents, embody the aftermath of public loss in The Wilderness. Their grief is both intimate and administrative—informing Desiree, enduring media reduction, sorting through a daughter’s life that the world wants to flatten into a headline.

Through them, the story shows how violence expands outward, leaving families to clean up not only belongings but narratives.

Miguel

Miguel is a key supporting figure in Nakia’s professional life in The Wilderness, representing trust, labor solidarity, and the fragility of operational stability. His sudden departure to care for his assaulted brother reveals how interconnected personal crises are with workplace survival, and how immigrant and working-class vulnerabilities constantly interrupt the dream of steady progress.

Miguel’s return later forces Nakia to renegotiate power and loyalty, illustrating her evolving leadership and the cost of building a business that depends on people whose lives are never fully predictable.

Reina

Reina brings tenderness and risk into Nakia’s world in The Wilderness. As a talented cook and later secret partner, she represents both desire and reinvention for Nakia, a chance to feel seen outside the pressures of ownership and public life.

Reina’s promotion shifts her from employee to trusted core, and that change tests Nakia’s ability to blend intimacy with authority. Reina’s presence highlights Nakia’s refusal to live in a single role—boss, partner, activist—without contradiction.

June

June, who cares for Bronze while Morris works, illustrates the extended-care web around January in The Wilderness. She functions as practical support, but her role also emphasizes how January’s domestic stability relies on others stepping in, reinforcing January’s fear that she is still the default center holding the structure together.

Bronze and Brook

Bronze and Brook, January’s sons, are not just background children in The Wilderness; they are the lived stakes of January’s decisions. Bronze represents the earlier version of motherhood that January expected to repeat—hard but survivable—while Brook’s postpartum period exposes how quickly a second child can transform care into collapse.

Their needs shape January’s body, marriage, and sense of self, embodying how love and depletion can coexist.

Little Terry

Little Terry, Terry Joyner’s teenage son, is a quiet emblem of parallel lives in The Wilderness. His existence confronts Danielle with a sibling relationship that could have been hers, spotlighting the way abandonment generates not only absence but alternate family trees that grow elsewhere.

He stays offstage, but his implied presence deepens Danielle’s grief for what was lost.

Aisha Miller

Aisha Miller appears through Monique’s DMs as a figure of contemporary activism in The Wilderness. Even without a long scene, her outreach signals Monique’s ongoing pull between grassroots work and public platform, hinting that Monique’s next steps are being shaped by networks that expect her voice to matter.

Themes

Caregiving, autonomy, and the right to choose an ending

Desiree’s trip with Nolan opens inside the everyday labor of keeping someone alive when their body is breaking down. The story doesn’t treat caregiving as a soft, sentimental act; it is physical, repetitive, and loaded with power.

Desiree gives insulin, moves his weakened limbs, manages dialysis, and watches his body lose parts. Those details show how care can become a form of intimacy that is also a trap: she is the person who knows his decline best, yet she cannot direct what happens next.

Nolan’s decision to pursue assisted suicide in Zurich forces the tension between love and control into the open. His planning is meticulous, almost bureaucratic, which emphasizes that his choice is not impulsive despair but a deliberate claim over his remaining selfhood.

He doesn’t want his final months defined by further amputations, diapers, or a hospital bed that erases his dignity. Desiree’s role becomes ethically unstable.

She is both witness and participant, trying to honor him while fearing the aftermath in her own conscience and in the judgment of her sister. Their arguments show that autonomy is never purely individual; it lands on the bodies and futures of the living.

Nolan’s warning about inheritance also adds a sharp edge: even at the threshold of death, material consequences and family politics press in. His death on the train before reaching the clinic complicates the idea of control even more.

He tries to script his exit, but mortality refuses a clean narrative. The suddenness of his death leaves Desiree with unfinished conversations, unresolved suspicions about possible other children, and a haunting sense that choosing an ending is always partly an illusion.

What remains is the emotional residue of care: the exhaustion, the love, and the quiet anger at a world where death can be both a feared loss and a chosen relief.

Estrangement, reconciliation, and the construction of family

Across the narrative, blood ties mean less than the everyday acts that make people family. Desiree and Danielle share history but live as strangers, their bond corroded by different memories of Nolan’s household and by years of distance.

That estrangement is not presented as a single conflict but as a slow drift shaped by grief, poverty, and misunderstanding. When Desiree asks Danielle to face Nolan’s plan, Danielle reacts with suspicion and moral panic, not because she lacks love, but because the sisters no longer trust each other’s judgment.

Later, Danielle’s meeting with Terry cracks open an older wound. His attempt to explain leaving Sherelle is met with Danielle’s rage at being abandoned, and the possibility that Nolan hid child support payments rewrites her entire sense of who carried the family.

This is a brutal reminder that family stories are often curated by whoever survives longest, and that children inherit not just money but versions of truth. At the same time, the book keeps showing family being built in other ways.

Desiree’s closest stability is Nakia, not Danielle. Their bond has shared routines, private jokes, and a kind of loyalty that is deeper than comfort.

The “Group of 7” dinners in Los Angeles extend that idea into community: debate, food, disagreement, and repair become rituals of belonging. Even with conflict, like Nakia and Monique’s late-night showdown about fame and values, the group functions as a living network that holds people when relatives cannot.

After Nakia’s death, Desiree’s devastation reads like the loss of a sibling, proving that chosen family is not secondary—it can be central. Danielle’s eventual impulse to call Nakia, and Desiree’s return to Nakia’s garden, suggest reconciliation is possible but never guaranteed.

It depends on risk, humility, and the willingness to live with shattered myths. In The Wilderness, family is not a stable noun but a verb: it is made, unmade, and sometimes remade through care, honesty, distance, and grief.

Money, inheritance, and class pressure inside Black life

Once Nolan dies, Desiree inherits a fortune that feels more like a complication than a rescue. The money comes from rental properties he neglected and insurance payouts he quietly arranged, tying her comfort to other people’s discomfort.

Tenants’ repair lists reveal Nolan as both beloved grandfather and careless landlord, forcing Desiree to confront how survival can slide into exploitation. Her reaction is not gratitude but paralysis.

She drinks, loses her job, and drifts because the inheritance arrives without a path for what to do with it or who to share it with. In that sense, wealth is shown as psychologically destabilizing when it lands on someone already hollowed out by loss.

The planner cousin’s advice to invest and “wait to decide” sounds sensible, yet it also highlights how class mobility demands new skills, new languages, and a self-concept Desiree doesn’t yet have. The club night with bottle service becomes a performance of upward identity—“young Black professionals” celebrating success—yet the night ends in violation and retreat, revealing how fragile those spaces can be.

The dinner-party debates in Los Angeles widen the theme. Talk of housing politics, NIMBY power, private equity, and homelessness makes clear that class struggle is not abstract theory but a daily urban reality.

Monique’s grim claim that the housed might eventually tolerate violence against the unhoused is extreme, but its shock value forces the others to look at the cruelty already embedded in property culture. Even among friends who share racial identity and progressive ideals, class position creates friction and defensiveness.

Desiree, positioned between inherited landlord wealth and emotional homelessness, becomes the living contradiction of this tension. The book refuses a clean moral ledger: Nolan’s accumulation provided Desiree security but also came from decisions that hurt tenants; activism can be sincere while still sheltered by privilege; friendship can be shaped by who has resources and who doesn’t.

What emerges is a portrait of class as a force that presses on every relationship, even in the most intimate corners of Black life.

Motherhood, reproductive choice, and the body under strain

January’s story brings motherhood in through anxiety, bodily upheaval, and the politics of deciding alone. Her pregnancy arrives in a moment of separation, precarity, and national dread, so the choice to keep the baby is both personal and a response to a world she doesn’t trust.

She writes a letter asking Morris to give up parental rights, not out of cruelty but from a belief that attaching herself to him will reproduce misery and dependence. Desiree’s phone call urging caution introduces the practical reality that parenthood is never just willpower; resources matter, and love doesn’t pay rent.

January knows this and still chooses solitude, revealing how autonomy can feel necessary even when it increases risk. The theme expands later when we see January postpartum in her suburban house.

The physical detail is relentless: nausea while breastfeeding, numb exhaustion, the default-parent burden, a body that feels broken. Domestic space becomes medical space—cold rooms, darkness, routines designed around survival.

Even with a husband and mother-in-law present, she is alone in the core of the experience, because the labor of keeping infants alive is lodged in her body. Her cryptic text—“Two things can be true at the same time”—captures the emotional logic of this theme.

She can love her children and resent the conditions of their care; she can want partnership and also want escape from it. The narrative doesn’t romanticize maternal endurance.

It shows how motherhood reshapes friendship too: Desiree drops everything to fly to Los Angeles when she senses danger, illustrating how women’s networks often act as the real safety net when institutions and partners fail. By placing January’s reproductive choice beside Nolan’s assisted-death choice, The Wilderness draws a quiet parallel between beginnings and endings: in both cases, bodily autonomy is contested, socially weighted, and never free from consequence.

The body is the site of love, risk, and decision, and the book insists on showing that clearly.

Grief, memory, and how places hold the dead

Loss in the novel is not a single event but a climate that characters live inside. Desiree’s grief begins before Nolan dies, during the long decline that erodes the person she knew.

After his death, she carries his ashes through the Alps, scattering them in villages he might have liked. That ritual is less about closure than about trying to translate a life into geography.

She steps off trains, chooses views, and releases fragments, as if distributing him across landscapes can soften the finality of disappearance. Back in Los Angeles, she keeps Nolan’s house unchanged, a small museum of denial and devotion.

The stillness of that house contrasts with the restlessness of her traveling, showing grief swinging between motion and stasis. Nakia’s death deepens the theme by revealing grief as communal and political.

Desiree’s shock at the news coverage—how quickly Nakia becomes a headline—exposes the way public language flattens private worlds. Cleaning Nakia’s kitchen, watching food rot, and seeing her untended garden overrun by weeds turn grief into a sensory inventory of what absence does to physical spaces.

Yet the garden also becomes a promise. Some plants survive despite neglect, and Desiree’s eventual return to restore it suggests memory can be caretaking rather than mere sorrow.

Places in the book don’t just host events; they store emotional residue. Harlem’s freezing studio, the evicted apartment January steps into, the Latin Quarter streets Nolan revisits, the Montparnasse red door he can’t face—each location is charged with what happened there and what could not happen there.

Even disaster, like the earthquake during the dinner party or the violent curfew protests, becomes part of the memory that binds people to Los Angeles. Grief, then, is inseparable from where it unfolds.

The Wilderness shows that mourning is often a negotiation with place: leaving it, returning to it, trying to remake it, and learning that the dead remain present through the rooms, streets, and gardens they once shaped.