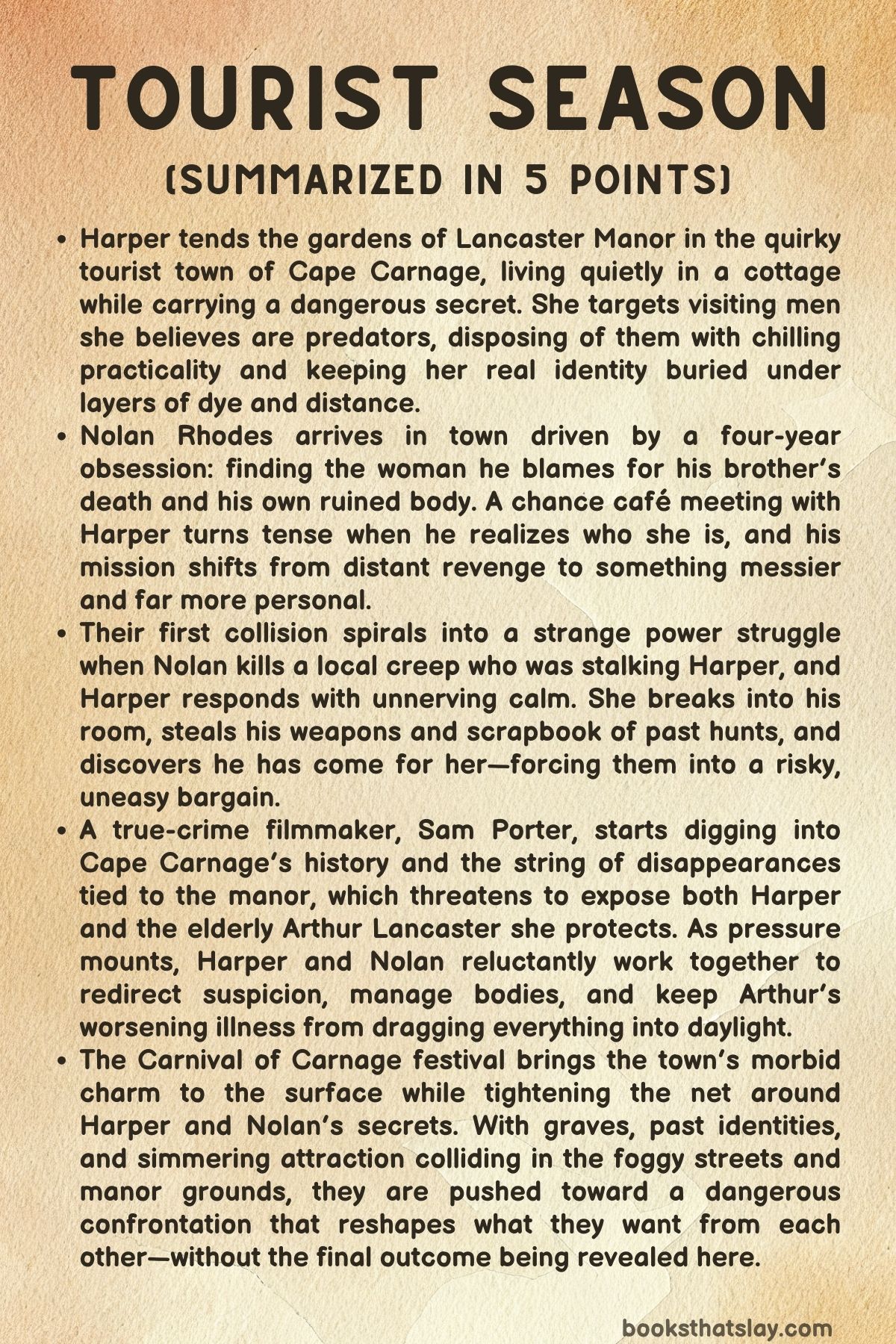

Tourist Season Summary, Characters and Themes

Tourist Season by Brynne Weaver is a darkly comic romantic thriller set in the foggy, tourist-hungry town of Cape Carnage. Harper Starling tends the lush gardens of Lancaster Manor, living quietly on the estate while hiding a violent past and a secret second life: she hunts and kills visiting predators who slip through the cracks of the law.

Her careful routine fractures when Nolan Rhodes arrives—an injured, relentless man who believes Harper is responsible for his brother’s death. What begins as a revenge mission turns into a volatile partnership, forcing them to confront buried crimes, shifting loyalties, and the town’s older, deeper bloodstains.

Summary

Harper Starling is Cape Carnage’s gardener, living in a cottage on the grounds of Lancaster Manor. To the town she is capable, private, and devoted to Arthur Lancaster, the elderly owner of the estate who is sliding into Alzheimer’s.

Privately, Harper is also a killer who targets tourists she believes are dangerous. After catching Bryce Mahoney taking up-skirt photos, she murders him and feeds his body into her beloved blue woodchipper, “Cookie Monster,” intending to bury the remains in her flowerbeds.

The machine jams when she hits a titanium plate in his leg, which unsettles her but doesn’t stop her. She finishes the job, fertilizes her garden with what’s left, and stores the plated bone in her fridge like unwanted evidence.

The morning leaves her tense, especially when she notices blond roots beneath her dyed hair, a reminder that she’s been living under a false identity since fleeing a brutal life four years earlier.

Later she visits Arthur to make lunch. He startles her with a knife, confused and paranoid, then insists someone has stolen his expensive shoes and a green sugar bowl.

Harper gently manages his fear, locating the bowl in his refrigerator and blaming his grandson Lukas to keep Arthur calm. Their bond is deep: Arthur is her refuge, and she is his steady anchor as his mind frays.

That same day, Nolan Rhodes arrives in town for a six-week stay at the Capeside Inn. Four years ago a hit-and-run in Maryland killed his brother Billy and left Nolan badly injured.

The driver, Harper Starling, was presumed dead in the crash, but Nolan discovered her bank account was emptied afterward. Since then, each anniversary he has hunted and killed someone connected to the case.

Now he has come to Cape Carnage for the final target: Harper herself.

Nolan meets Harper by chance at a café, not recognizing her at first. Their conversation is awkwardly flirtatious, with Harper improvising lies about what she’s carrying in foil and giving him a tour of the town’s morbid attractions.

Just as she’s about to say her name, a barista says “Harper,” and Nolan’s mood shifts. Back at the inn, he confirms through old photos that she is the driver he’s been chasing.

His rage sharpens when he sees her hugging a man outside a gym, mistaking it for intimacy.

That night Nolan sneaks onto Lancaster Manor. Near Harper’s cottage he hears explicit talk and sees a figure in the shadows watching her through the window.

The voyeur is Jake Hornell, a local gym creep Nolan earlier noticed on a drone shoot for Sam Porter, a true-crime documentarian filming in town. Nolan kills Jake with a garrote, dismembers him, and buries the body near the Ballantyne River.

In the morning Harper discovers Jake’s severed head on her bird feeder, already being pecked by her raven Morpheus. Instead of panic, she reacts with grim practicality, annoyed at the inconvenience.

Nolan steps out, revealing himself and pressing her about what she did to Jake. Before the clash can escalate, Harper’s neighbor Maya appears, and Nolan invents a story about special-effects props.

Once Maya leaves, Nolan warns Harper she can’t escape him.

Harper breaks into Nolan’s inn room that day. She finds weapons and a leather scrapbook filled with hunted men, burial maps, and trophies.

Paging backward, she finds proof that Nolan’s brother died because of her and realizes Nolan is in town to kill her. She steals the scrapbook and his gear, leaves a taunting note, and slashes his SUV tire.

Nolan returns to find his plan disrupted. Furious yet intrigued by her boldness, he tracks her to the manor, where he encounters Sam Porter and learns about the town’s legends of a past killer called La Plume, a figure linked to Lancaster Manor.

Harper confronts Nolan beside her woodchipper as she disposes of Jake’s remains. He’s horrified by her method; she is unimpressed by his moral outrage.

When Nolan mentions Sam’s documentary, Harper panics—Sam’s digging could expose Arthur’s secrets and her own hidden identity. They strike a tense deal: Nolan will help drive Sam out of Cape Carnage, and Harper will return the scrapbook and weapons while keeping enough leverage to protect herself.

Their alliance is sealed with threats, sarcasm, and a spray of foul repellent to Nolan’s face.

The next days bring pressure from multiple directions. Lukas reveals he has sold a parcel of Lancaster land by the Ballantyne River to a company called Viceroy.

Harper is shaken because Nolan buried Jake there, and Arthur’s own old records mark the same land as a disposal site. If construction begins, graves may be exposed, and everything could collapse.

Arthur then falls and is hospitalized. While staying with him, Harper decides to create an alibi for Arthur and distract Sam.

She plants incriminating keepsakes in an abandoned farmhouse and anonymously tips Sam to the location. She also targets Mr. McMillan, a violent drunk who attacked a pregnant nurse at the hospital. Luring him from his motel, she brings him to her yard and kills him when he tries to fight free.

Nolan arrives mid-scene, alarmed by her recklessness, and their partnership strains under accusations of manipulation and control.

At the Carnival of Carnage festival, Sam corners Harper and recognizes her as the Harper Starling presumed dead in Maryland. He hints he’s found the planted evidence and wants to talk.

Harper denies him, but the encounter rattles her. Nolan, noticing her fear, stays close.

Their bond grows in uneasy quiet moments, even as danger tightens around them.

The next crisis hits when Arthur secretly retrieves his “murder bag” from Nolan, then wanders to the cemetery. Harper and Nolan find him injured beside a dead tourist whose face bears the imprint of Arthur’s cane.

They scramble to cover the death. Harper takes Arthur home while Nolan goes to handle the body, but Sam ambushes Nolan, kidnaps him, and chains him inside the Lancaster distillery.

Sam intends to film a confession, threatening to expose both Nolan and Harper.

Harper tracks Sam to the distillery, knocks out his drone operator Vinny, and rescues Nolan. Together they overpower Sam and send him falling to the level below.

They clean the scene, steal anything linking Sam to them, and hide both Sam’s gear and the tourist’s body in a freezer at Lancaster Manor.

Before dawn Nolan dives offshore and finds a half-submerged camper van. In its records and old videos, he realizes Harper is actually Autumn Bower, a vanished influencer who once traveled with Adam Cunningham—meaning Harper’s entire identity is a carefully maintained lie.

In the aftermath, Sheriff Yates discovers Sam’s body, interrogates Vinny, then reveals himself as La Plume. He kills Vinny, stages the scene, and vows to protect Arthur and Autumn, leaving Harper and Nolan tied not only to each other but to a town where the law and the killers are the same people.

Characters

Harper Starling / Autumn Bower

Harper is the novel’s volatile center: outwardly a quiet, indispensable gardener of Cape Carnage, inwardly a woman shaped by trauma, rage, and a strict private code. Her daily life at Lancaster Manor is built on careful concealment—hair dye, false accounts, a cottage that doubles as sanctuary and killing ground—because she is not only hiding from law enforcement but from a past self she can’t fully erase.

In Tourist Season, Harper’s violence is not random; it is targeted, ritualized, and justified through her personal morality, where she frames herself as a predator of predators. The woodchipper “Cookie Monster,” the raven Morpheus, and her use of bodies as fertilizer show how completely she has fused death with her identity as a cultivator of life—she is literally feeding the garden with her victims, turning horror into growth.

Yet her tenderness toward Arthur exposes a second core truth: she is capable of deep, loyal love, and that love is her most dangerous vulnerability. Harper’s arc is a constant push-pull between control and unraveling; she is hyper-competent in planning and cleanup, but emotionally combustible when her secrecy, Arthur’s safety, or her autonomy are threatened.

Her relationship with Nolan activates every layer of her—fear, attraction, competitiveness, and the longing to be seen without being destroyed—forcing her to confront whether her code is justice, survival, or simply the last story she can tell herself to keep living.

Nolan Rhodes

Nolan arrives in Cape Carnage carrying grief that has fossilized into purpose. The hit-and-run that killed his brother Billy and shattered his own body is not just backstory—it is the engine of his identity.

In the years since, Nolan has sculpted himself into a methodical avenger, marking anniversaries with killings, preserving tattooed skin as trophies, and building a scrapbook of violence that functions like both evidence and scripture. He sees himself as righteous, but his righteousness is inseparable from obsession; his hunt for Harper is less about law or closure and more about a need to impose meaning on loss.

What complicates him in Tourist Season is how quickly vengeance collides with desire. His first encounter with Harper carries an almost comic flirtation that instantly turns to shock when he realizes who she is, and from there his emotions swing between lethal intent and reluctant fascination.

Nolan is dangerous not only because he is skilled, but because he is emotionally split: part of him wants to punish Harper, part of him wants to understand her, and part of him is drawn to someone as broken and ferocious as he is. His growing protectiveness toward her and Arthur reveals a buried capacity for care that contradicts the monster he has been becoming.

By the time he uncovers Harper’s true identity as Autumn, Nolan is no longer a simple hunter; he is a man forced to face the terrifying possibility that vengeance won’t resurrect the dead, and that intimacy with his target might be the only thing that makes him feel alive again.

Arthur Lancaster

Arthur is the moral fog of the story: an aging patriarch sliding into Alzheimer’s whose gentleness and confusion mask lethal history. He is introduced as Harper’s closest friend, a man she feeds and comforts, and that tenderness is real—Arthur’s dependence on Harper is sincere, and his affection for her is paternal, sometimes mistaken, sometimes piercingly lucid.

But Tourist Season steadily reveals that Arthur is not merely a vulnerable old man; he is tied to Cape Carnage’s legacy of disappearances and to the mythic killer La Plume. His “murder bag,” his sedatives, and the cemetery death suggest that his decline has not erased old habits, only blurred their boundaries.

Arthur is unsettling because his violence cannot be cleanly separated from his illness: sometimes he seems to manipulate his frailty to move unseen, other times he is genuinely lost inside his fractured memory. That ambiguity makes him tragic rather than purely monstrous.

He embodies the theme of time corrupting truth—how past sins don’t vanish but rot into the present—and his relationship with Harper becomes a twisted mirror of devotion, where love compels her to protect him even as that protection drags her deeper into danger.

Sam Porter

Sam is the story’s embodiment of predatory curiosity, a man who cloaks exploitation in the language of truth-seeking. As a true-crime documentarian, he comes to Cape Carnage claiming to chase history, but what he really hunts is narrative ownership—he wants to be the one who “discovers” La Plume, who exposes the secrets that other people bled to bury.

In Tourist Season, Sam’s methods reveal his ethics: flying drones over private land, planting himself in people’s lives, and wielding evidence as leverage rather than responsibility. His interest in Harper is not concern but opportunity, and once he recognizes her as the missing Harper Starling, he shifts from investigator to blackmailer, using Nolan as bait and filming coercion like it’s content.

Sam’s downfall comes from underestimating the people he studies; he believes himself the author of the story, but in a town built on real monsters, his performative bravado makes him prey. Sam matters less for who he is as a person than for what he represents: the way tragedy becomes entertainment, and how the hunger to expose evil can become a form of evil itself.

Sheriff Yates / La Plume

Sheriff Yates is the novel’s final turning knife, a figure who initially seems like a weary local cop managing tourist chaos, then emerges as Cape Carnage’s hidden architect of violence. His calm authority and selective pressure on Nolan suggest long familiarity with the town’s darker rhythms, and the epilogue confirms that familiarity is authorship: he is La Plume.

In Tourist Season, Yates functions as both protector and predator. His decision to kill Vinny, stage his own injury, and promise to shield Arthur and Autumn reveals a personal code eerily similar to Harper’s—he too believes in controlling who deserves to live or die to preserve a larger order.

What makes him chilling is his institutional camouflage; he is not an outsider killer but the law itself, which lets him pick threats and erase them. Yates also completes the book’s theme of layered secrecy: the town’s mythology is not history but an ongoing system maintained by those in power.

His protection of Arthur and Harper is not benevolence but an investment in a legacy of hidden crimes, suggesting that in Cape Carnage, survival often depends on being useful to a worse monster.

Lukas Lancaster

Lukas is a pragmatic heir caught between affection for his grandfather and the looming weight of Lancaster secrets. He appears as capable and grounded, helping Harper with the distillery shed and the gravity racer, and he seems to trust her instinctively, which signals how embedded she is in the family ecosystem.

His decision to sell land by the Ballantyne River introduces a crucial pressure point: Lukas represents the forward-moving, business-minded future that unknowingly threatens to unearth the past. In Tourist Season, Lukas is not a villain; he is normalcy intruding on a carefully curated evil.

The fact that Harper entrusts him with Nolan’s weapons and contingency plans shows he occupies a middle space in her world—someone she respects enough to involve, but not enough to tell the full truth. Lukas’s role underlines how fragile the secret life of Cape Carnage is; even well-meaning, ordinary actions can destabilize a decades-old web of violence.

Irene

Irene, the elderly innkeeper of the Capeside Inn, serves as a gentle gatekeeper to Cape Carnage and a subtle enabler of its hidden horrors. She is warm, chatty, and disarmingly simple, praising Harper’s gardens and giving Nolan information without realizing the danger she’s facilitating.

Yet her closeness to Harper—implied by Harper’s access to a master code—suggests that Irene is more woven into the town’s informal trust networks than she appears. In Tourist Season, Irene embodies the everyday face of a place saturated with death: she thrives on tourist business, treats outsiders kindly, and remains oblivious (or willfully blind) to the blood beneath her floors.

Her character highlights how communities normalize darkness when it keeps the town running, and how innocence can become a quiet accomplice.

Morpheus

Morpheus, Harper’s raven, is more than a gothic accessory; he is an extension of her psyche and a living barometer of the ecosystem she has built. Raised by Harper, he mirrors her voice, guards her space, and feasts on what she discards, making him a literal participant in her rituals.

His behavior—croaking insistently, pecking Jake’s eye, dropping objects—blurs the line between pet and conscience, as if nature itself is both complicit and watchful. In Tourist Season, Morpheus symbolizes Harper’s fusion of nurture and savagery: she loves him, feeds him, and yet uses him as part of her disposal system.

His mimicry also reinforces the theme of unstable identity—voices repeating, selves overlapping—while his presence adds a constant, unsettling reminder that in Cape Carnage, even the animals are shaped by human violence.

Maya

Maya is a small but important counterweight to the story’s extremes. As Harper’s neighbor and the owner of a stain-remover business, she brings mundane community life into a narrative of killers and secrets.

Her cheerful interruptions and easy acceptance of Nolan’s absurd lie show her as trusting and practical, not naive so much as socially conditioned to accept Cape Carnage’s eccentricity. In Tourist Season, Maya’s role is to remind both Harper and the reader that normal people exist on the edges of horror, living beside it without seeing its true outline.

Her casual request for strawberries and her willingness to leave quickly also illustrate how thin the membrane between ordinary friendliness and catastrophic truth can be.

Jake Hornell

Jake is the archetypal local creep whose presence catalyzes the central relationship. He is a voyeur, a gym-bro stalker who objectifies Harper and assumes entitlement to her body from the shadows.

His death at Nolan’s hands is not just a plot beat; it is a character revelation for both leads. In Tourist Season, Jake functions as a foil: he is a predator without a code, driven by selfish appetite, which allows Nolan to justify killing him and Harper to accept it with eerie gratitude.

His severed head on the feeder becomes a grotesque gift, a violent meet-cute that sets the tone for Harper and Nolan’s bond—two people who recognize monstrosity in each other and find it perversely compatible.

Vinny (Drone Operator)

Vinny is a minor character but a key piece in Sam’s apparatus. He is the hired eye, more technician than mastermind, enabling Sam’s intrusions without carrying Sam’s ego.

His presence shows how modern surveillance turns people into tools for someone else’s story. In Tourist Season, Vinny’s quick knockout by Harper and his later death at Yates’s hands emphasize how disposable such enablers are in a town where the real power is lethal.

He also serves as a reminder that curiosity without context is dangerous; he participates in trespass and exposure without understanding the scale of what he’s poking.

Dr. Reid

Dr. Reid’s role is brief but emotionally pivotal.

As Arthur’s physician, he provides the clearest clinical confirmation of Arthur’s decline, describing the B12 deficiency and worsening Alzheimer’s that Harper has been trying to manage alone. In Tourist Season, Dr. Reid is the voice of reality intruding on Harper’s self-reliance. His calm medical framing forces Harper to confront that Arthur’s condition is progressing beyond what love can patch over.

He represents institutional care that Harper distrusts, and his scene deepens the tragedy of Arthur by grounding his behavior in illness even as the plot keeps hinting at his violent past.

Mr. McMillan

McMillan is a grotesque, chaotic catalyst rather than a fully formed character: a drunk, violent patient who harms a pregnant nurse and triggers Harper’s fury. His purpose in Tourist Season is to show Harper’s reflexive moral logic in action.

She does not simply kill because she can; she kills because she decides he deserves it, and she uses his death as a strategic tool to protect Arthur. McMillan’s brutality makes Harper’s retaliation feel, in her mind, like justice, but the risk and savagery of the scene also reveal how quickly her code can become excuse.

He exists to expose the fine line between righteous violence and reckless compulsion.

Billy Rhodes

Though dead before the novel’s present, Billy is a persistent emotional character through Nolan’s memories and grief. He represents the life Nolan lost, the innocence that shaped Nolan’s obsession, and the unhealed wound every killing tries to cauterize.

In Tourist Season, Billy’s importance is not in actions but in absence; his death is the gravity that bends Nolan toward vengeance, and the tenderness Nolan occasionally shows hints at who he might have been if Billy had lived. Billy is the silent judge in Nolan’s head, and the tragedy is that no amount of blood can bring that brother back.

Themes

Vigilante Justice and Moral Ambivalence

In Tourist Season, violence is not an interruption of normal life but a chosen method of order-making in a town that markets death as entertainment. Harper’s killings are driven by a personal code: she targets tourists she judges as predators, photographing creeps, abusers, and men who feel dangerous in ways the law either can’t catch or won’t prioritize.

That code gives her a sense of purpose and even calm; the act of feeding bodies into the woodchipper and fertilizing her garden is described with the same routine attention she gives to pruning and planting. The story never lets that feel simple.

Harper’s criteria are subjective, and the reader is made to sit inside her certainty while also noticing how easy it could be to rationalize mistakes. The titanium plate in Bryce Mahoney’s leg becomes a symbol of the unexpected resistance reality offers to clean moral narratives: even a “deserving” target can leave a mess she didn’t anticipate, materially and ethically.

Nolan operates under a parallel logic. He has spent four years hunting Harper for a hit-and-run that killed his brother, and he marks anniversaries with killings of people he connects to that event.

Like Harper, he frames murder as accountability. Yet his scrapbook—tattooed skin strips, maps of burial sites, photographs of terrified victims—exposes how vengeance transforms into ritual and obsession.

The themes collide when Nolan kills Jake Hornell, a creep harassing Harper, in a moment that is both protective and possessive. Harper’s reaction to Jake’s head on her feeder is telling: she is not horrified by the death but by the inconvenience and disrespect.

The moral center of the book shifts constantly, forcing the reader to confront how easily “justice” becomes a mirror for trauma, ego, and desire. No authority figure offers a reliable alternative; even the sheriff is ultimately a serial killer in disguise.

The result is a world where morality is not anchored by institutions or social norms but by raw personal conviction, and those convictions are always unstable. The theme doesn’t ask the reader to approve of vigilante killing, but it does insist on examining why it can feel emotionally coherent to people who have been failed, harmed, or left with no other language for safety.

Identity, Disguise, and the Right to Rebuild the Self

Harper’s life in Cape Carnage is built on disappearance. She dyes her hair, uses a false name, monitors the forum that once searched for her, and keeps her real past sealed behind routine labor and carefully managed relationships.

Her gardening job at Lancaster Manor gives her a cover that is more than practical; it lets her become someone defined by caretaking rather than catastrophe. The small detail of blond roots showing through the dye is a quiet reminder that identity is never fully erased, only managed.

The story treats identity as a survival project, not a fixed essence. Harper is hiding because her former life was brutal, and the narrative respects that flight as necessary rather than cowardly.

At the same time, the disguise comes with psychological cost. She measures safety by the silence of the internet, by whether strangers have posted about her, by whether her hidden objects stay hidden.

She lives under the constant pressure that a name spoken at the wrong moment can open the door to death. Nolan’s arrival turns that threat into a living person.

To him, Harper is not the careful gardener friend of Arthur but the driver who stole his brother, the ghost who escaped consequences. His hunt is a refusal to allow self-reinvention; he believes a person must remain accountable to who they were at the worst moment of their life.

The later revelation that Harper once lived as Autumn Bower, a public-facing vanlife influencer, complicates her secrecy further. It suggests that she has been multiple people before, and each identity carried its own myth, audience, and expectations.

The theme asks what it means to own your story when the world’s version of you is wrong, incomplete, or weaponized. Sam Porter’s documentary role brings this to a head: he wants to freeze Harper and Arthur into characters for public consumption, turning their pain into content.

Harper’s panic at Sam is not only fear of arrest but fear of losing control over meaning. The book implies that rebuilding the self is a moral act in a world that often refuses to let people change.

But it also acknowledges the tension between reinvention and responsibility, especially when the past holds real victims. Identity here is neither mask nor truth alone; it is a contested space where survival, guilt, and autonomy fight for the right to define who someone is allowed to become.

Care, Loyalty, and the Cost of Attachment

Beneath the gore and dark humor, Tourist Season is held together by fierce, complicated forms of care. Harper’s devotion to Arthur Lancaster is the clearest example.

She cooks for him, manages his confusion, protects him from distress, and even lies to preserve his dignity. Her relationship with him is not transactional; it’s a chosen family bond formed in the aftermath of her escape.

She sees his decline as something she must buffer with tenderness and control, and her violence often traces back to safeguarding that fragile world. When Arthur thinks she’s an intruder and threatens her, Harper responds with patience and familiarity rather than fear.

This care, however, becomes ethically tangled because Arthur is not an innocent dependent. The cemetery scene reveals that he has his own “murder bag” and continues killing tourists while slipping into Alzheimer’s.

Harper’s loyalty forces her into damage control, hiding bodies, staging alibis, and redirecting suspicion. The theme explores how love can become complicity when the person you protect is dangerous.

Nolan’s loyalty to his brother Billy is another version of attachment that drives the plot. His grief is real, and his need to make someone pay is his way of preserving Billy’s importance.

Yet grief curdles into something that isolates him from normal empathy. Killing each anniversary is a grim devotion ritual that keeps his brother present but also traps Nolan in permanent aftermath.

When Nolan and Harper form an uneasy alliance, attachment shifts again. Their attraction grows alongside mutual recognition: each sees in the other a person shaped by trauma who understands the language of violence.

Nolan holding Harper’s hand in the theater, or making dinner in her cottage, shows the possibility of care that is not purely protective but genuinely connective. Still, that care is always threatened by their histories and by the instability of trust.

Harper preps Lukas to send evidence to the FBI if she dies; Nolan digs the grave he once meant for her even while wanting her near. The story presents attachment as necessary for human survival, but never safe.

Caring for someone can make you brave, but it can also make you reckless, blind, or willing to cross lines you once swore mattered. In this world, loyalty is both refuge and hazard, and the book stays honest about the emotional relief it brings without ignoring the violence it can excuse.

Power, Voyeurism, and the Commodification of Violence

Cape Carnage thrives on tourism that is explicitly macabre, and that setting lets Tourist Season interrogate how violence becomes spectacle. The town sells haunted history and disappearance lore as attractions, drawing visitors who want to consume fear from a safe distance.

Harper reacts against this in a twisted way: she targets tourists who are predators, but she also targets the entitlement of outsiders who treat the town, and by extension its people, as objects. The up-skirt photographer Bryce and the masturbating stalker Jake represent voyeurism at its most literal—men who take pleasure in watching without consent.

Their crimes are small-scale versions of the broader tourist dynamic the book critiques. Nolan’s drone work for Sam Porter adds another layer: technology extends the gaze, turning private spaces into footage.

Sam is the clearest embodiment of commodification. He arrives to make a true-crime documentary, positioning himself as a truth-seeker while using disappearance and murder as career fuel.

His obsession with finding La Plume and exposing Arthur is not motivated by justice for victims so much as by narrative payoff and audience impact. Even when he threatens Nolan and Harper, it is framed as leverage to secure a story, not to prevent future harm.

The theme points to how true-crime culture can flatten human lives into content arcs, where moral outrage is sincere but still profitable. Harper’s counter-move—planting keepsakes to redirect Sam—shows her understanding of narrative manipulation.

She knows what props a documentarian will chase, how certain objects can create a convincing story trail. Power here depends on who controls the story.

Sam’s camera and drone are tools of dominance; Harper’s secret acts are also about controlling what others see. Nolan’s scrapbook is another private archive of violence, but one that he keeps for himself, a personal museum of revenge.

The final revelation that Sheriff Yates is La Plume completes the argument: institutional power can be another kind of hidden audience, watching, deciding whose deaths matter, and staging performances of justice when convenient. The book doesn’t moralize about watching violence; instead it shows how watching can be a form of participation, and how cultures built on spectacle create the conditions for real harm.

In Cape Carnage, the gaze is never neutral. It is desire, entitlement, surveillance, and commerce all at once, and the bodies left behind are the price of turning suffering into entertainment.

Trauma, Grief, and Cycles of Violence

The characters in Tourist Season are not casually violent; they are forged by prior catastrophe, and their actions keep replaying that history. Harper’s past is hinted as brutal enough to make disappearance feel like the only route to life.

That background shapes her present emotional range. She can be tender with Arthur, sarcastic with Nolan, and methodical with a corpse, all without the story suggesting she is numb.

Instead, trauma has reorganized her priorities. Safety, control, and prevention of future harm matter more than conventional moral boundaries.

Her garden becomes a metaphor for this: she creates beauty out of rot, but only by managing death directly. Nolan’s trauma is explicit.

The hit-and-run that killed his brother and mangled his own body splits his life into before and after. His yearly killings are not just revenge but grief management.

He can’t resurrect Billy, so he keeps the moment alive through repetition, casting new victims into the crash’s shadow. The theme emphasizes how grief can harden into identity when there is no closure.

Nolan believes killing Harper will complete a story that has remained open for four years, but his growing tie to her threatens that illusion. Their intimacy after she drugs him with mushrooms is a sharp pivot: it suggests that trauma bonds can create genuine desire, but also that the line between comfort and manipulation is thin when both people are broken in related ways.

Arthur’s Alzheimer’s adds a different kind of cycle. His memory loss lets old violence continue without reflection; he drifts into killing almost by habit, then forgets why or how.

Harper’s attempts to cover for him show how trauma doesn’t only live in individuals—it spreads through relationships. Protecting Arthur forces Harper to re-enter danger repeatedly, escalating risks until the walls start to crack.

The land sale near the Ballantyne River creates the ticking clock for exposure, showing how violence, once buried, never stays fully contained. Even when characters try to stop, practical reality—graves, evidence, witnesses—pulls them back.

The final act with Sam, Vinny, and Sheriff Yates shows the cycle widening to include outsiders who exploit or threaten the fragile balance. Yates as La Plume represents the most chilling aspect of cyclical violence: a system that quietly sustains murder under the cover of order.

By the end, the book has built a world where trauma generates violence, violence creates new trauma, and everyone is trapped in some version of that loop. The theme’s power lies in refusing easy redemption.

Healing is not presented as a simple exit. Instead, the story asks what people do when their pain has already rewritten their sense of normal, and whether breaking a cycle is possible when the only tools you’ve been given are the ones that built it.