What We Can Know Summary, Characters and Themes

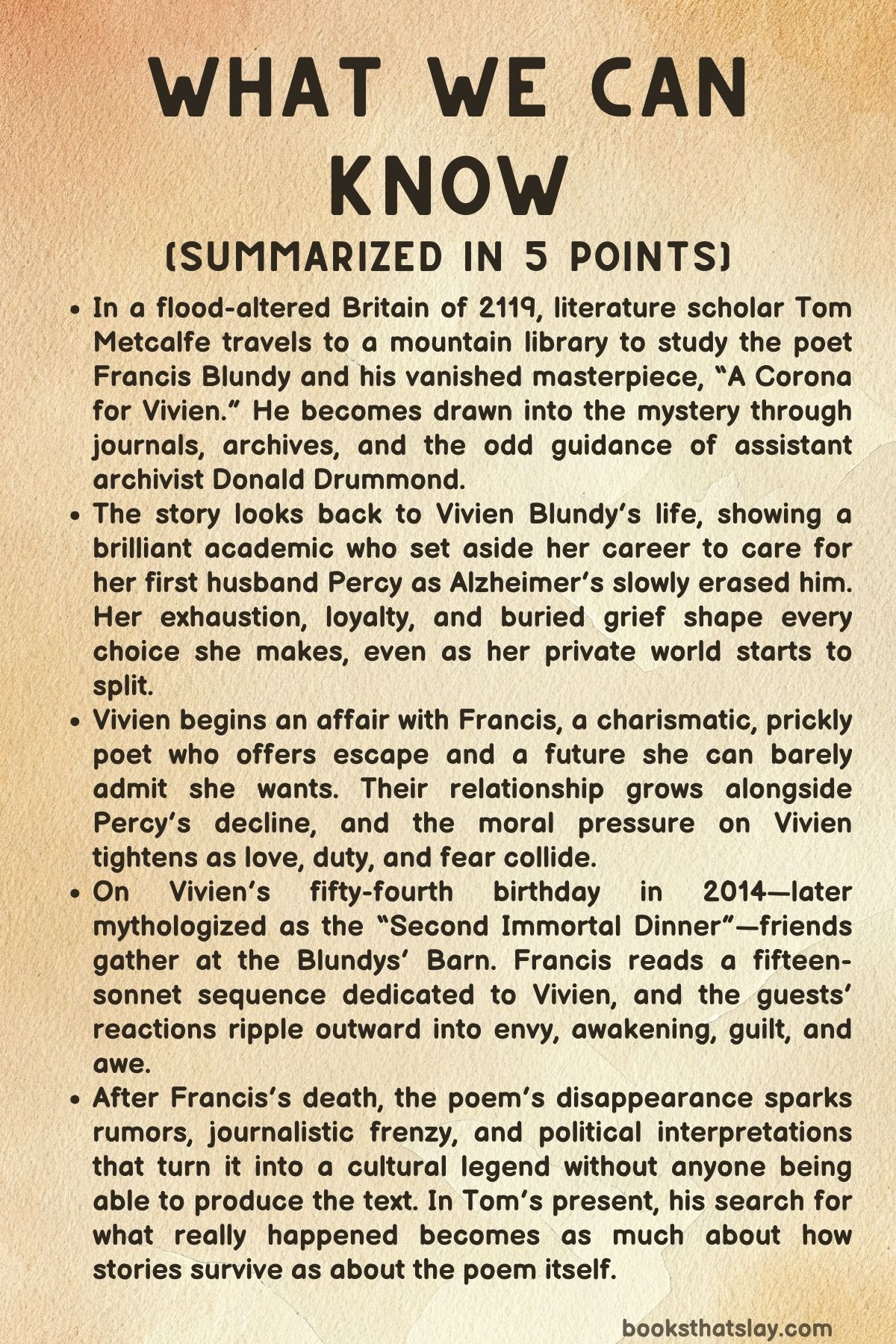

What We Can Know by Ian McEwan is a novel that looks back from a climate-altered future to a single night in 2014 when a famous poet unveiled a remarkable work that later disappeared. The book follows Thomas Metcalfe, a scholar in the year 2119, as he researches Francis Blundy and his wife Vivien, hunting for the truth behind the lost poem “A Corona for Vivien.”

As Thomas pieces together journals, letters, rumors, and his own reconstructions, the story becomes both a mystery about art and a study of marriage, guilt, and the long human habit of rewriting the past to survive it.

Summary

In May 2119, Thomas Metcalfe, a literature scholar living in a flooded, reshaped Britain, travels to the Bodleian Snowdonia Library near Maentwrog-under-Sea. The old mainland has become islands, Oxford now sits by inland water, and scholars study the early twenty-first century the way earlier ages studied antiquity.

Thomas’s obsession is the vanished poem “A Corona for Vivien,” written by the renowned poet Francis Blundy and read aloud only once, on Vivien Blundy’s fifty-fourth birthday in October 2014. That single reading became legendary, then frustratingly unreachable when the text never surfaced.

Thomas wants to write the history of the poem and its disappearance, even if that means filling gaps with careful imagination. His colleague Rose, also his estranged wife, warns him that invention muddies scholarship.

He agrees in principle, but in practice he cannot resist trying to make the past whole.

At the library, assistant archivist Donald Drummond eagerly supplies Vivien’s journals and seems desperate to discuss a strange string of numbers in her last notebook. Thomas, focused on the poem, keeps Drummond at arm’s length.

He studies Vivien’s fifth journal volume, which covers the days leading to the birthday dinner. The entries are heavy with domestic detail—lists of food, gardening notes, weather records—and light on direct emotion.

Yet between the lines a life emerges: Vivien was once an Oxford academic with ambition, but years of caregiving and marriage redirected her into supporting other people’s needs. She first devoted herself to her husband Percy Greene, a gifted violin maker who developed early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Later she became the practical center of Francis Blundy’s life in rural Gloucestershire, running the household and protecting his working conditions while he pursued poetry.

The journal reconstructs the day of the famous dinner. On a windy October morning Vivien shops for quail and vegetables, helps a farmer clear a fallen sapling, and notes unsettling shifts in climate without turning them into politics.

A parcel arrives for Francis: champagne from their nephew Peter, now a physicist in California. Francis is prickly about gifts, and his inability to offer Vivien warmth on her birthday leaves her quietly hurt.

In his study, however, he has prepared his own present: a single fair copy of a fifteen-sonnet corona titled “A Corona for Vivien,” written on vellum. He intends it to exist only in this form, with all drafts destroyed.

He sees it as one of his best works.

Guests arrive through the afternoon. Novelist Mary Sheldrake comes with her husband Graham after a brutal car argument in which Graham confessed an affair.

Mary has her own lover and feels a fierce, private appetite for change; outwardly she and Graham perform civility while their marriage collapses in real time. Other friends gather: Tony Spufford, a botany professor, and veterinarian John Bale, who tells a vivid story about performing surgery on a tortoise and a snake, unsettling the table with talk of animal pain.

Harry Kitchener—Francis’s editor and brother-in-law—arrives with his wife Jane. Their presence steers talk toward London scandals and cultural gossip.

A kitchen mishap briefly fractures the mood when Mary drops and shatters a salad bowl that Jane once made as a wedding gift; Vivien calms her and keeps the evening on track. Finally Harriet and Chris Gage come late, frazzled by their baby’s crying at home.

As drinks flow, Francis launches into one of his standard speeches dismissing climate warnings as alarmist theatre. The others listen out of politeness or fatigue.

Dinner itself is a success: roasted quail, mushrooms, cauliflower, potatoes, and wine. Conversation ranges over the 2012 Olympics, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and the Assange controversy.

Yet Francis keeps glancing at the mantel clock where the vellum scroll is hidden, waiting for the moment to read his gift. Harry gives a long, over-generous toast praising Francis, partly driven by guilt because he has decided to abandon a promised biography of the poet.

Francis cuts him short, insisting the night belongs to Vivien.

He retrieves the vellum and reads the full corona aloud. When he finishes, silence fills the room.

He feels spent and proud, kisses Vivien, and hands her the only copy. Harriet begins to cry, then claps; the others follow with praise and toasts.

Each guest reacts in their own private way—Mary shaken into self-doubt about her novels, Graham hollowed by jealousy, Harry anxious about his withdrawal from the biography—but what survives publicly is unanimous admiration. This is the night that later commentators label the Second Immortal Dinner, echoing earlier literary gatherings that birthed legend.

In the days after, the poem’s influence spreads even without publication. Mary, stunned by the corona’s physical immediacy, decides her own work has been too safe and resolves to write differently.

Harry, despite abandoning the biography, sends Francis a rapturous letter praising the poem in ecstatic detail, hoping to keep peace within the family. That letter later becomes one of the few public traces of the corona.

After Harry dies in 2016, the letter is published, and a storm of speculation begins. Journalists demand the poem.

Bloggers crown it a masterpiece suppressed for political reasons. Harriet Gage writes a high-profile article framing it as a warning about a planet under threat, and rumors surface that powerful interests paid to bury it.

Vivien refuses all requests to release it. Francis falls ill with pancreatic cancer and dies soon after.

Vivien withdraws further, eventually leaving the Barn to live in Scotland with Jane. When Vivien dies years later, the corona is still missing, and its absence only enlarges its myth.

Thomas’s research then forces him deeper into Vivien’s earlier life. He uncovers her marriage to Percy Greene and the long years she spent caring for him as Alzheimer’s hollowed out his memory and personality.

During a respite arrangement she escaped to Oxford and met Francis at a reading in 2001. Their affair began cautiously but grew into a force that divided her life.

As Percy’s condition worsened, Francis pressed her to place him in care. When she resisted, he proposed something darker.

One night he arrived at her house, Percy fell down the stairs, and Francis finished the killing with a mallet. Vivien, terrified and exhausted, followed his instructions to erase evidence, and authorities ruled it an accident.

Later Francis used her desperate emails as leverage, insisting she had consented. Trapped by guilt, need, and lack of alternatives, Vivien married him and moved to the Barn.

Their marriage was tense, threaded with her affairs and his moods, while the unspoken crime sat between them like a sealed room.

Against that history, Thomas interprets the corona as more than a love poem. When Vivien finally read it closely after the birthday dinner, she recognized her first husband’s illness and death reshaped into Francis’s art, with an implied confession and a demand that she accept his version of their lives.

Furious and frightened by what the poem might reveal, she took the scroll to the dairy and burned it in the stove. The act erased the text but could not erase its shadow.

Back in 2119, Thomas receives a delayed letter from Drummond. Drummond’s niece Dolly has solved the journal’s number code: not a phone number, but coordinates leading to the Blundys’ old dairy on a Cotswold island.

A note suggests something buried four meters from its south-east corner. Thomas fears Drummond might go himself, so he asks Rose to help.

Though their marriage is broken, they share the urgency of the discovery. They hire a captain and boat, camp on the island, fight through forest and bog, and dig beside the ruins.

They recover a sealed steel container holding Percy’s cherished violin and a folder of Vivien’s confession—prose, not poetry. As Rose reveals she is pregnant, the find becomes personal as well as scholarly: a buried past surfaced beside the possibility of a different future.

Thomas accepts that the poem itself is gone, but its absence has shaped history. Across the century people invoked the unseen corona in shifting ways—first as an emblem of devotion, later as a rallying point for environmental resistance, and finally as a symbol of what was lost.

The book ends with Thomas holding only traces: a confession, a violin, and the knowledge that art can outlive itself even when its words are ash.

Characters

Tom / Thomas Metcalfe

Tom, also referred to later as Thomas Metcalfe, is the story’s future-facing consciousness: a humanities scholar living in a Britain transformed by catastrophic floods, trying to stitch together truth from fragments. He begins as a weary academic, emotionally blunted by the collapse of his marriage with Rose and by the numb routines of teaching and archival work.

Yet beneath that apathy sits a deep hunger for meaning, and the vanished poem becomes his conduit back to life, purpose, and intimacy. His fixation on “A Corona for Vivien” reveals both his scholarly devotion and his personal need to believe that the past can still speak coherently to the present.

Thomas’s tension with Rose over method—her insistence on evidence versus his impulse to reconstruct and imaginatively fill gaps—shows him straddling the border between historian and novelist. By risking a physical expedition to the Blundys’ island and by accepting that his story will always be partial, he becomes a figure of fragile hope: someone who cannot restore what was lost, but can keep its shadow alive.

In What we can know, Tom embodies the human drive to make narratives out of ruins, even when certainty is impossible.

Vivien Blundy (née Greene)

Vivien is the emotional core of the novel, a woman defined by devotion, guilt, endurance, and an almost frightening capacity to compartmentalize pain. Once an Oxford academic with ambition, she gradually disappears into the roles demanded of her by others: first caregiver to Percy Greene as Alzheimer’s dismantles him, then manager, driver, secretary, and life-raft to Francis Blundy.

The journals Tom reads are deceptively domestic, filled with recipes and weather notes, which is precisely the point: Vivien has trained herself to survive by recording practicalities rather than naming despair. Her inner life is shaped by layered trauma—her accidental death of her baby Diana in youth, the slow erasure of Percy, her complicity in Percy’s murder, and her later marriage to the man who killed him.

She is not naïve about her compromises; she knows what she is hiding and why, even as secrecy corrodes her from within. Vivien’s refusal to publish the Corona and her eventual burning of it are not petty obstruction but acts of self-defense and moral control: she will not allow a poem, however beautiful, to rewrite her life into someone else’s fantasy or to expose the crimes threaded through her marriage.

In her final years, living with Jane and burning parts of Harry’s archive, Vivien becomes the guardian and destroyer of memory at once—someone who believes that some truths must be preserved only in controlled form, and some must die with her. She is tragic not because she is weak, but because she is strong in ways that leave no clean exit.

Francis Blundy

Francis is a brilliant poet with a corrosive ego, equal parts visionary artist and morally stunted tyrant. He lives through language and image, yet fails repeatedly at ordinary empathy, treating Vivien’s labor as assumed atmosphere rather than gift.

His skepticism toward climate change is less intellectual than temperamental: a refusal to accept limits or external authority, mirroring his need to dominate conversations and relationships. Francis’s pride in the Corona—its strict Petrarchan architecture, its uniqueness, his destruction of drafts—shows an artist obsessed with control and legacy.

That same hunger for control curdles into cruelty: he pressures Vivien to institutionalize Percy, then crosses into murderous “solution,” carrying it out with chilling pragmatism while framing it as mercy. Even after the murder, he binds Vivien to him through leverage, insisting her desperation equals consent, revealing a mind that rationalizes domination as inevitability.

The Corona itself becomes the clearest expression of Francis’s paradox: a poem of extraordinary craft and sensory force, but also an appropriation of Vivien’s reality, reshaping Percy’s suffering and death into poetic material centering Francis’s own myth of marriage. Francis is thus both the creator of beauty and the engine of ruin—someone who can write devotion more convincingly than he can live it.

Donald Drummond

Donald Drummond, assistant archivist at the Bodleian Snowdonia Library, is a small but crucial hinge between past and future. Socially awkward, intensely literal, and quietly lonely, he latches onto puzzles with almost childlike fixation, especially the string of numbers in Vivien’s journal.

His eagerness with Tom in the archives suggests a man starved for intellectual companionship, and his inability to read Tom’s disinterest makes him both faintly comic and oddly poignant. Drummond’s illness and physical absence later heighten his role as a messenger rather than a hero—he does not seek adventure for himself but trusts scholarship enough to summon someone else into it.

By involving his niece Dolly and urging Tom to act, he shows a moral instinct for preservation: he senses that what is hidden matters not for gossip but for cultural memory. Drummond represents a quieter kind of courage: not the dramatic risk-taker, but the guardian who notices, deciphers, and passes the torch.

Dolly Drummond

Dolly, Donald’s fourteen-year-old niece, appears briefly yet sharply as a symbol of the future’s clarity amid adult confusion. Her brilliance in mathematics allows her to reframe the mysterious “phone number” as map coordinates, and this decisive shift unlocks the entire buried legacy of the Blundys.

She is presented as quick, practical, and unpretentious, contrasting with the intellectual vanity of older scholars. Dolly’s contribution suggests that the survival of knowledge may depend less on inherited authority and more on fresh, cross-disciplinary thinking.

In a narrative haunted by lost texts and distorted memories, Dolly is a bright flare of competence cutting through fog.

Rose

Rose is Tom’s estranged wife, sharp-minded, ethically rigorous, and emotionally bruised. She teaches alongside Tom and is the counterweight to his imaginative reconstruction, insisting on boundaries between what can be proven and what is invented.

Yet her seriousness is not sterile: when she reads Drummond’s letter she responds with urgency and hope, showing that she still cares about both scholarship and Tom, despite the wreckage between them. Her affair with a student, Kevin Howard, complicates her moral authority without erasing it; she owns her mistakes and tries to end them.

On the island expedition, Rose proves resourceful and disciplined, laying down safety rules and pushing through hardship. Her pregnancy, revealed at the moment of discovery, reframes her as someone stepping toward life even while living among ruins.

Rose’s arc is about cautious rebirth: she does not romanticize the past, but she is willing to build a future if honesty and mutual effort can survive.

Percy Greene

Percy is Vivien’s first husband, a gifted violin maker whose warmth and outdoors-loving temperament make his later decline especially brutal. His early-onset Alzheimer’s is rendered not as a background tragedy but as a long dismantling of personhood, forcing Vivien into a caregiver role that drains her identity and isolates her.

Percy’s illness brings out not only pity but anger in Vivien—rage at the theft of their shared future and at the cruelty of watching kindness become volatility. His half-finished Guarneri replica violin becomes a silent register of what Alzheimer’s interrupts: patience, craft, continuity.

Percy is also the story’s moral wound. His death is engineered by Francis and enabled by Vivien’s exhaustion and ambivalence, making Percy both victim and haunting presence long after he is gone.

Even in absence, he anchors Vivien’s guilt and motivates her final act of burial and confession.

Rachel

Rachel, Vivien’s sister, is a figure of limited but essential support. She tries to help with Percy’s care, bringing her son Peter to give Vivien brief respite, yet her help is constrained by her own life pressures—marital struggles and later breast cancer.

Rachel represents the ordinary limits of family loyalty: willing to step in, but unable to rescue Vivien from the scale of her entrapment. Her presence also highlights Vivien’s increasing secrecy; Vivien drafts but deletes the email that would have exposed Francis’s murder plan, showing how Rachel is both lifeline and witness Vivien cannot bear to face.

Peter

Peter evolves across timelines from a child who adores Percy and happily works in his shed to a brilliant physicist in Pasadena whose gift of champagne indirectly sets the Corona dinner in motion. As a boy, he becomes collateral damage in Percy’s decline, especially after Percy strikes him in confusion, a moment that shatters trust and pushes the family further apart.

As an adult, Peter is distant in geography and temperament but still connected by affection for Vivien. His presence underscores the generational ripple of trauma: the child shaped by illness and secrecy becomes the adult who unknowingly participates in the rituals of a past he cannot fully know.

Mary Sheldrake

Mary is a celebrated novelist whose personal and artistic identity cracks open on Vivien’s birthday. She arrives at the Barn in the wake of a marriage-breaking argument with Graham, outwardly competent but inwardly electrified by betrayal and liberation.

Her secret affair with Leonard and her readiness to imagine a new life show a woman already in transition. The Corona hits her like revelation; she is moved not only emotionally but professionally, realizing that her own novels may have been “bloodless” compared to the poem’s physical vividness.

Mary’s response to the poem is creative envy turned into resolve: rather than dismissing Francis, she allows the shock to reorient her craft. She represents how art can destabilize even the successful, forcing change not through moral lesson but through aesthetic intensity.

Graham Sheldrake

Graham is Mary’s husband, caught in late, messy honesty about his affair. His confession ignites their argument on the drive and turns the evening into a performance of civility over rubble.

His snooping on Mary’s phone and confrontation about Leonard reveal insecurity and moral hypocrisy—he wants freedom for himself but cannot bear Mary’s parallel betrayal. Graham is not deeply explored beyond this fracture, but his role is to expose how quickly intimacy collapses into surveillance and mutual cruelty once trust is broken.

Leonard

Leonard appears only through implication and messages, but his shadow is important: he is the imagined future Mary leans toward, the proof that her marriage’s end is not only loss but opening. Because he remains unseen, he functions more as a catalyst than a character, embodying desire for reinvention.

Tony Spufford

Tony, the botany professor, belongs to the Barn’s social circle, a quieter presence who helps round out the dinner’s mix of professions and temperaments. His background in plants contrasts with Francis’s climate-change dismissal, suggesting a man for whom ecological reality is daily knowledge.

Though he does not dominate scenes, his role is to represent the kind of educated listener Francis expects: polite, observant, and unwilling to battle ego in a social setting.

John Bale

John, the veterinarian, is a humane observer whose profession tunes him to suffering in bodies—animal and human alike. His opening storyline with the injured snake shows patience, steady skill, and a moral attentiveness that extends beyond usefulness or public recognition.

At the Corona dinner, he notices the cruelty of others’ mockery about reptile surgery but chooses restraint, not out of cowardice but out of an instinct to keep peace and watch carefully. John’s sensitivity makes him a silent moral barometer during the poem reading; he absorbs rather than performs.

Later, through his narrative frame, he helps present the Corona as not merely literary artifact but lived event that reorders people’s inner worlds.

Sam and Jackie Bryant

Sam and Jackie, retired volunteers at John’s clinic, are gentle embodiments of ordinary decency. Their repeated visits to check on the snake, their decision to foster it at home, and their celebratory pub meal after its release portray care as communal habit rather than grand gesture.

They highlight one of the novel’s quiet arguments: that survival—of animals, memories, or people—depends on small acts done faithfully.

Harold “Harry” Kitchener

Harry is Francis’s editor and brother-in-law, a man who understands genius but is exhausted by its vanity. At the dinner he delivers a lush speech praising Francis, partly sincere and partly motivated by guilt because he has decided not to write Francis’s biography.

His retreat from the project stems from clear-eyed recognition that Francis would make the work impossible through control and thin-skinned rage. Yet Harry cannot bring himself to be fully honest; his later extravagant letter praising the Corona is a compromise meant to preserve family peace.

That duplicity is not villainy but weariness—the fatigue of managing an artist who demands emotional tribute at the cost of others’ truth. Harry’s unsent confessional email hints at a more tangled private life, suggesting he too lives with submerged guilt.

His later death and the publication of his praise become the spark that turns the dinner into legend, showing how even cautious half-truths can fuel myth.

Jane Kitchener

Jane, Harry’s wife and Francis’s sister, operates largely in the background but becomes vital in the aftermath. At the dinner she is a steady social presence, and her handmade salad bowl—broken accidentally by Mary—symbolizes the fragile gifts of long relationships.

After Harry’s death she retreats with Vivien to Scotland, and together they burn parts of Harry’s archive, an act that links her to Vivien’s ethic of controlled memory. Jane’s alliance with Vivien suggests loyalty not to literary history but to the people bruised by it.

Harriet Gage

Harriet arrives at the birthday dinner exhausted by motherhood, then is openly moved to tears by the Corona, becoming the first to clap and pull the room into admiration. Later, as a journalist, she transforms into a public mythmaker, writing a major article that frames the Corona as suppressed masterpiece and climate warning, helping launch decades of rumors.

Harriet’s dual role shows how private emotion can become public narrative, and how cultural longing often reshapes art into the message the age wants. She is neither cynic nor saint; she is someone whose genuine awe becomes professional mission.

Chris Gage

Chris, Harriet’s husband, is mostly peripheral at the dinner but becomes morally charged through Vivien’s later affair with him. He represents the porousness of the Barn’s social world, where intimacy slides into betrayal quietly over years.

His presence reinforces how Vivien seeks escape or affirmation outside Francis, and how the circle around the poet is never as stable as it appears.

Todd

Todd, Harriet and Chris’s baby, is a tiny but telling force. His screaming delays their arrival, reminding the dinner guests that life continues in raw, bodily demand even amid high literary ritual.

Todd symbolizes the future pressing against a room preoccupied with legacy.

Cyril Baker

Cyril is Tom’s medieval historian housemate, defined by his unnervingly immaculate bathroom and quiet domestic order. He is a minor figure but functions as a contrast to Tom’s drift and disarray.

Cyril’s control over small spaces hints at how people respond differently to a destabilized world: some cling to routine and cleanliness as a bulwark against chaos.

Jo Mideksa

Jo is the experienced captain Tom and Rose hire to reach the Blundys’ island. Practical, competent, and unromantic about risk, she enforces the rules of the physical world—tides, military restrictions, survival basics—that scholarship alone cannot negotiate.

Her shallow-draught boat Salty and her willingness to wait offshore make her the enabling presence behind the expedition’s success. Jo represents grounded professionalism, the kind that makes intellectual quests possible.

Kevin Howard

Kevin, Rose’s student and brief affair partner, appears indirectly as a marker of Rose’s loneliness and error. His role is less about his own personality and more about what the affair reveals: Rose’s vulnerability, her desire to feel chosen, and her effort to cut off the entanglement once she confronts its cost.

Martha MacLeish

Martha, Vivien’s dying friend, is a quiet threshold figure in Vivien’s past. Her illness and death set the stage for the train-station episode with the abandoned boy, nudging Vivien into a moment of moral action.

Even in absence, Martha’s death signals the world’s ongoing losses that surround Vivien.

Christopher (the abandoned boy)

Christopher, the three-year-old found alone on a rural platform, appears briefly but powerfully as a test of Vivien’s instinct to protect. Vivien’s refusal to let a stranger take him and her determination to stay with him until police arrive reveal her courage and moral clarity in a moment where she is not yet trapped by secrecy.

Christopher is a mirror of innocence at risk, foreshadowing how later, in her own life, Vivien will be unable to protect the vulnerable person closest to her—Percy.

Diana

Diana, Vivien’s baby who died in her twenties, exists only in confession, yet she shapes Vivien’s entire emotional architecture. The accident—drunken neglect leading to the child’s death—plants in Vivien a lifelong conviction that she does not deserve motherhood or forgiveness.

This guilt fuels her self-erasure into caregiving and her tolerance of suffering, as if punishment were a moral duty. Diana is Vivien’s private ghost, the origin point of her belief that love can be lethal.

Themes

Memory, Erasure, and the Ethics of Reconstructing Lives

A future scholar trying to recover a vanished poem sets the emotional and philosophical stakes: what survives of a life when its most famous artifact is missing, and with what right does anyone rebuild what cannot be proven? Tom’s fixation on “A Corona for Vivien” begins as professional curiosity but quickly turns into a test of how memory operates at individual and cultural scales.

Vivien’s journals are full of weather, errands, food, and gardening—an archive of the ordinary that refuses to organise itself into the kind of neat narrative Tom wants. Their very banality is the point: lived experience is mostly unshaped time, and meaning is often retrofitted by those who come later.

In the flood-altered Britain of 2119, the past is physically fragmented into islands, mirroring the way the historical record is broken. Tom’s colleague Rose warns him against invention, while Tom argues that coherence demands imagined links.

The tension isn’t academic nitpicking; it is moral. To supply missing motives or scenes is to risk stealing a person’s reality, especially when that person—Vivien—is already a figure whose work, sacrifices, and voice were overshadowed in her lifetime.

The novel keeps returning to acts of erasure. Francis destroys drafts to control his legacy.

Vivien later burns the final vellum to prevent the poem from outliving her context and to protect herself from exposure. Harry’s archive is edited and partially burned.

These are not just plot turns; they form a chain of competing claims over what the past will be allowed to say. Even the activist afterlife of the lost Corona shows memory turning into a social tool: people reshape the unseen poem into whatever their era needs—a climate manifesto, a love hymn, a moral warning—until the absence becomes more influential than any text could be.

The book asks whether remembrance is ever neutral. Every preservation is a choice, and every choice creates a new silence.

Tom’s project therefore sits inside a paradox: he wants truth, but the pursuit itself imposes form, emphasis, and interpretation. In What we can know, memory is both refuge and threat, and the drive to recover it can be as intrusive as forgetting.

Care, Dependency, and the Unseen Labor of Love

Vivien’s life is structured by care long before the future scholars encounter her. The journals’ domestic texture—shopping routes, meals planned, plants tended, bodies managed—is not filler; it is the record of a person whose days are consumed by keeping others alive and functioning.

Her first marriage to Percy shows care as devotion that slowly becomes captivity. Alzheimer’s turns their partnership into an asymmetry: she becomes nurse, guard, interpreter, and sole witness to his dwindling self.

The emotional reality is less about noble sacrifice than about fatigue that corrodes identity. She loves Percy, yet she also experiences rage at the way illness eats their shared future.

The half-finished violin she finds in his shed becomes a symbol of what care costs: the maker is still present in traces of skill and tenderness, but the person she knew is unreachable. Care also isolates.

Friends and institutions fail to offer adequate support; respite is rare, and when it comes it carries guilt. This isolation primes Vivien for Francis’s attention, not because she is frivolous but because she is starved for companionship that recognises her as more than a caretaker.

Yet care repeats in different form when she moves to the Barn. There, she runs Francis’s life—correspondence, travel, household, social smoothing—while his art takes centre stage.

The pattern is grimly consistent: the person doing the work that sustains daily life becomes structurally invisible to the one being sustained. Even Francis’s birthday gift, intended as adoration, functions like an entitlement claim.

The Corona imagines a marriage full of nature and mutuality, then expects her gratitude for a life she did not live. In that sense, the poem is another unpaid demand placed on her: to confirm him, to validate a story that serves his self-image.

The book also contrasts care for humans with care for animals. John Bale’s meticulous repair of the injured snake is a counterpoint to the dinner conversation that treats reptile suffering as a joke.

His tenderness is practical rather than performative, suggesting that genuine care is quiet, specific work. By placing this scene alongside Vivien’s caregiving, the novel widens the theme beyond romantic or familial duty into a question about how societies rank suffering and decide what deserves attention.

Care becomes a field where moral worth is measured, but also where power hides. Vivien’s care is exploited; Percy’s dependency makes him vulnerable; Francis’s charisma turns care into a resource he assumes will be supplied.

What we can know doesn’t romanticise caregiving. It shows love as something enacted through repetitive labor, while also showing that such labor can be coerced, taken for granted, and used to trap the caregiver inside someone else’s story.

Power, Complicity, and Moral Choice Under Pressure

The murder of Percy is the most overt ethical rupture in the narrative, but the theme is broader than a single act. The novel studies how moral boundaries erode through exhaustion, fear, desire, and social imbalance.

Francis’s power over Vivien is built over time, not suddenly. He offers escape from her grinding life, then slowly frames Percy’s continued existence as an obstacle to “their” future.

His contempt for activists and his towering confidence at the dinner are extensions of the same posture: he sees himself as the one who defines reality, and he expects others to adjust. When he proposes killing Percy, he isn’t asking permission as an equal; he is testing how far his authority reaches.

Vivien’s refusal is clear, yet her desperate emails and depleted state give him material to twist into consent. The killing itself is staged as a “solution” he decides to execute, with Vivien reduced to an almost dissociated witness.

Her complicity is real—she doesn’t stop him, and she follows his instructions afterward—but the novel refuses simplistic judgment. It asks what agency means when a person is cornered by fatigue, love, guilt, financial limits, and the gradual normalisation of the unthinkable.

The authorities’ acceptance of the death as accident adds another layer: institutions are willing to let violence disappear when it fits a convenient script of tragic mishap and devoted spouse. Francis then cements control through blackmail logic—if he falls, she falls.

Their later marriage becomes a partnership founded on shared crime and shared silence. Power in this world is not only physical; it is narrative.

Francis uses poetry, charisma, and social standing to shape how events will be remembered. Vivien counters with secrecy, omissions in her journals, affairs that reclaim slivers of autonomy, and eventually the decisive act of burning the Corona.

Her destruction of the poem is not just self-protection; it is a refusal to let Francis’s aesthetic framing dominate the moral meaning of Percy’s life and death. The future reception of the lost poem continues the theme in a new setting.

Rumours of fossil-fuel suppression and activist appropriation show power operating through interpretation, turning art into a weapon in political struggle. Tom’s own project risks another kind of dominance: by reconstructing what he cannot know, he could overwrite Vivien’s intentions with his own.

The book wants the reader to sit with the discomfort that moral responsibility is often distributed across time, relationships, and systems. Nobody here is purely monster or purely victim.

What we can know portrays ethical life as something negotiated under pressure, where choices are constrained yet still consequential, and where the stories told afterward can deepen harm or open a path to truth.

Art, Ownership, and the Limits of Representation

The Corona is a technical feat, a love gift, and a trap all at once, so the book uses it to interrogate what art can claim about other people’s lives. Francis believes his poem is the highest expression of devotion: one perfect copy, no drafts, an object that asserts purity through exclusivity.

Yet that very exclusivity is a form of control. By insisting on a single vellum scroll, he makes Vivien not only the subject but the custodian of his legacy.

When he reads it aloud at dinner, he creates a social reality around it—silence, applause, tears, immediate legend—before Vivien has even absorbed what it says. Her private reading later reveals the poem as an appropriation of her trauma.

It reenacts Percy’s illness and murder, placing Francis and Vivien at the centre of a story Francis wants to sanctify. In doing so, the poem crosses an ethical line: it turns someone else’s suffering into his aesthetic material without consent.

The question is not whether art may address pain, but who has the right to frame it and for what end. Vivien’s furious response and her decision to burn the Corona declare that representation has limits.

Some experiences are not available to be transmuted into beauty by those who caused them. The theme reappears through Mary Sheldrake, whose reaction during the reading is both admiration and self-indictment.

She recognises that art can expose the thinness of her own work and can demand a fuller realism. Her epiphany shows art as a disruptive force that reshapes creators, not just audiences.

At the same time, her response underscores the gap between public aesthetic experience and private moral context. She is moved by vivid physicality, unaware of the coercion and confession embedded in the poem.

That gap is crucial: art can produce genuine feeling even when its origins are tainted, and audiences may not know what they are endorsing. The later century’s obsession with the lost Corona intensifies the issue of ownership.

As the poem disappears, it becomes a blank screen for collective desire. People claim it for climate politics, for ideals of marriage, for ecological mourning.

The unseen text is treated as common property, even though Vivien’s act of burning was itself a form of authorship over meaning. Tom’s chase for the poem also raises the question of whether art belongs to history or to the people it was made for.

In What we can know, art is powerful but not sovereign. It can illuminate, distort, console, blackmail, and survive as rumour.

The novel keeps asking what happens when aesthetic value collides with lived truth—and it answers by granting Vivien the final authority over how her story will, and will not, be told.

Environmental Change and the Human Talent for Denial

The future setting is not a gimmick; it is the consequence of attitudes already visible at the 2014 dinner table. Britain’s transformation into an archipelago after catastrophic floods shows climate change as an accumulated moral failure, not a sudden apocalypse.

In Vivien’s journals, weather is endlessly noted—wind, warmth, odd seasonal shifts—yet her observations remain private, filed among recipes and errands. She senses change but does not act, suggesting how easily awareness can coexist with inertia when daily survival is already consuming.

Francis embodies denial in a more aggressive form. His dinner monologue dismissing climate warnings as scams is not merely contrarian; it is a defence of status, comfort, and self-image.

By ridiculing activists in traffic and later lecturing guests by the fire, he performs certainty as dominance. Others listen politely, avoiding conflict, which mirrors the broader social pattern: denial is sustained not only by loud voices but by quiet accommodation.

The novel ties this to personal denial as well. Vivien avoids writing certain truths in her journal; Harry avoids telling Francis he won’t write the biography; Tom avoids confronting the emotional void in his own marriage until the expedition forces intimacy.

Environmental denial is thus placed within a continuum of human avoidance. People avert their eyes from what threatens their stable narratives, whether that threat is planetary collapse or the ethical horror of a murder they helped enable.

The later myth of the Corona as a climate-warning masterpiece shows how societies rewrite the past to find missed signals. Activists project ecological prophecy onto a poem that, in its real private meaning, was about something darker and more personal.

This mismatch is revealing. It suggests that, even after disaster, humans try to redeem history by imagining that art had already said what politics could not face.

The book doesn’t sneer at that impulse; it understands it as grief seeking purpose. Yet it also insists on the costs of delay.

The flooded, militarised islands Tom and Rose must navigate are the material residue of earlier complacency. The expedition itself—difficult, cold, root-choked, and risky—feels like a late, physical reckoning with problems that should have been addressed when solutions were easier.

In What we can know, environmental collapse is not separate from intimate life. It presses on marriages, careers, scholarly projects, and myths.

The theme finally becomes a question about responsibility across time: how much of the future is built by the small refusals, polite silences, and self-serving certainties of the present.