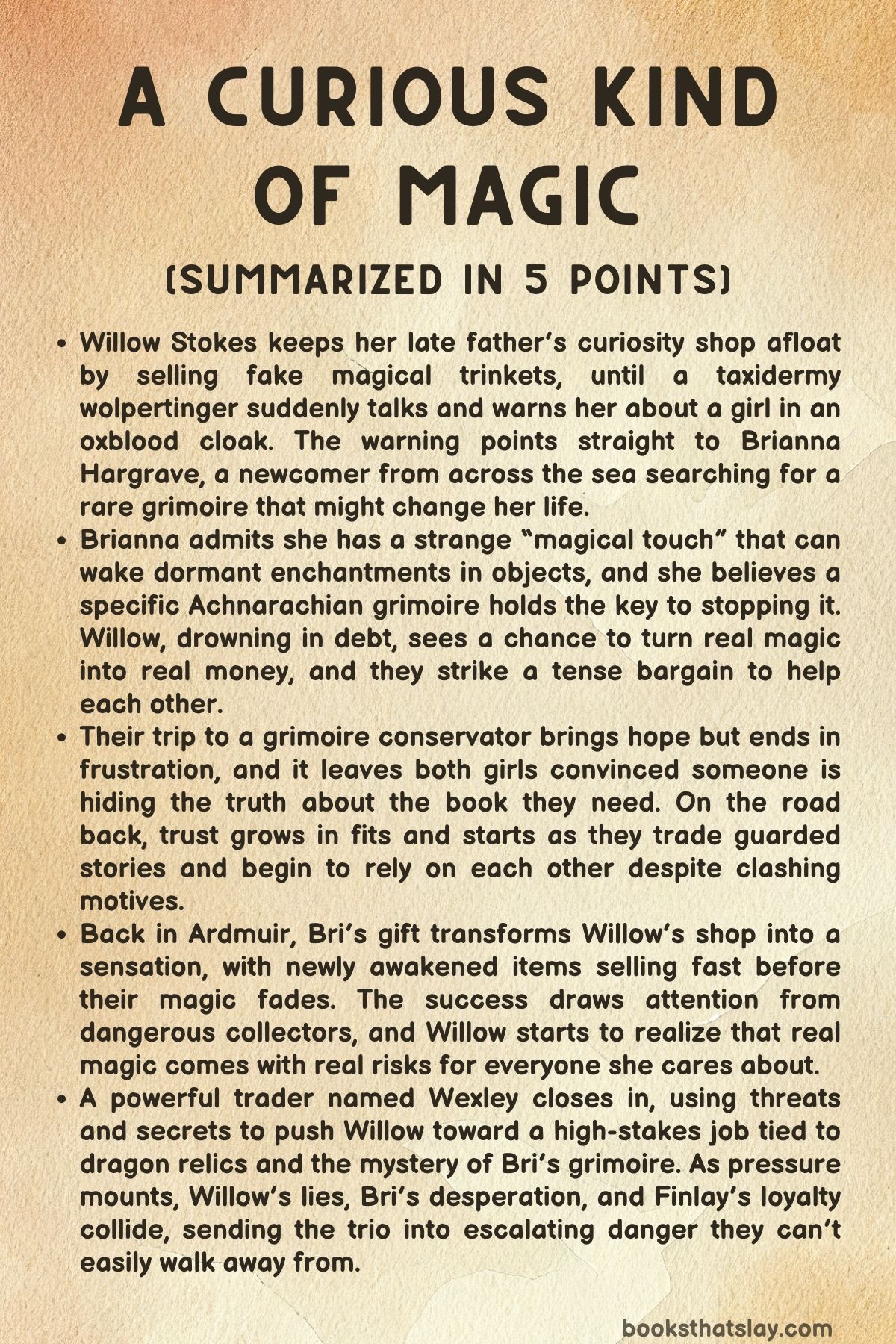

A Curious Kind of Magic Summary, Characters and Themes

A Curious Kind of Magic by Mara Rutherford is a cozy, fast-moving fantasy set in the seaside town of Ardmuir. Willow Stokes, broke and wary, runs her late father’s curiosity shop, which sells fake magical trinkets he once used to scam tourists.

Her life changes when a taxidermy wolpertinger in the shop speaks a warning and a mysterious newcomer, Brianna Hargrave, arrives searching for a truly magical grimoire. As Willow and Bri form an uneasy partnership, real magic reenters Willow’s world, bringing profit, danger, and the chance to redefine who she is beyond her father’s shadow.

Summary

Willow Stokes keeps Edward Stokes’s Cabinet of Magical Curiosities afloat in Ardmuir, though she knows nearly everything inside is a fraud left behind by her con man father. One rainy September day, a dusty wolpertinger near the door speaks in a deep voice, warning her to “beware the girl in the oxblood cloak.” Moments later a young woman with dark hair and a foreign accent steps into the shop.

She introduces herself as Brianna Hargrave, newly arrived from Carterra, and asks about grimoires—books that are magical in themselves. Willow has never seen one and directs her to Anatolia’s bookshop, where Bri works as a new assistant.

When Bri touches the wolpertinger on her way out, it repeats its warning, startling them both.

That evening Willow’s best friend Finlay Barrow tells her about a Sapphire Islander in town claiming to sell real dragon teeth. Dragon parts are legendary for granting powerful abilities, but most are fakes.

Willow, desperate for rent money, agrees to go investigate. At breakfast in the Four Swans, Willow finds Finlay already talking to Brianna.

Bri looks wealthier than she claims to be, and she admits she is hunting a particular Achnarachian grimoire tied to her family. Willow insists that if Finlay helps Bri search, Bri must return to Willow’s shop so Willow can see whether the wolpertinger will speak again.

Bri reluctantly agrees to meet privately. In her room she demands proof that Finlay can help; he suggests a conservator named Mr. Tell who might know rare grimoires.

Willow offers to go too, hoping to turn Bri’s interest into profit.

Before leaving the hotel, Willow overhears the Islander, Torion, selling a dragon tooth for an enormous sum to a collector named Oliver Wexley. Torion promises more dragon bones later.

Realizing the tooth might be genuine, Willow decides to watch their next exchange at the docks.

Bri delays, and Willow’s finances worsen. Finlay returns with proof of Bri’s seriousness: a silver thimble she gave him.

When he puts it on Willow’s thumb and stabs her hand, the knife rebounds off an invisible shield. The object is truly magical, though Bri warns its effect will fade quickly.

Willow and Bri travel together to see Mr. Tell. The trip is tense at first, but along the way Bri reveals she was born in Achnarach, raised in Carterra after her family emigrated, and returned in secret to find the grimoire before Yule.

She also confesses that her touch awakens latent magic in objects, except for grimoires. She believes her ability is a curse and wants a grimoire containing a spell to remove it.

Willow is stunned but also sees opportunity.

Mr. Tell denies having any such grimoire and grows hostile. Bri, frantic, tries pulling books from shelves, causing chaos.

Willow drags her out, and they flee. Bri suspects Tell knows more but fears people will exploit her.

Willow realizes the wolpertinger may be genuinely magical and that Bri’s presence likely triggered it. Despite her own motives, Willow promises to keep helping Bri search.

Returning home, Willow finds Finlay has cleaned her cottage, fed her kitten Argyle, and baked pie. His quiet care embarrasses and comforts her, and she notices how much she relies on him.

The next day Bri and Finlay come to the shop. Willow stops Bri from touching the wolpertinger again, wanting to save its possible wish for later, but asks her to test other items.

Bri identifies a witch’s broom; when she touches it, it lifts her into the air. The proof that real magic hides among the fakes shocks Willow.

She sells the broom to a fisherman for enough money to pay months of arrears and protect her shop, though she feels guilty knowing the enchantment will last only a day.

That night Willow spies on Wexley and Torion at the docks. They bargain over dragon bones—teeth, scales, plates—each tied to a different power.

Torion mentions a grimoire called The Oxblood Book and says Mr. Tell reported two girls searching for it, including an outlander with Achnarachian ties. Willow realizes Wexley is tracking Bri and hears that magic-wielders can be hunted for their bones.

Fear for Bri’s safety mixes with her growing suspicion that Wexley is dangerous.

Demand for magic swells after rumors of the broom spread. Willow convinces Bri to move into her cottage rent-free and use her touch to identify more items, promising to be honest about the enchantments’ short lifespan.

Bri agrees with strict boundaries: no physical contact with people and a written contract. Together they reopen the shop as a legitimate business, selling newly awakened trinkets and gaining respect in town.

Wexley begins appearing among customers, watching Bri closely. As they settle into a routine, Bri shares her painful family history: parents who fear her power, a grandmother who loved her, and a deadline to return by Yule with her “curse” broken, because her mother is dying.

Willow meets Wexley at his townhouse and sees his massive private collection. He claims friendship with her father, tests her for weakness, and reveals he knows she once sold fake magic.

He blackmails her into a theft: travel to the Sapphire Isles and steal a fossilized dragon egg from Azure Cay, promising his whole collection in payment and threatening Bri and Finlay if she refuses. Terrified, Willow lies to her friends, saying she’s found a lead to break Bri’s curse, and agrees to go.

The plan collapses into danger. Willow and Bri are captured and end up in Blackbay Prison.

A witch named Freya visits them and insists Willow herself is a suppressed witch. She says Willow’s hidden magic must be used with the dragon egg to escape.

When guards return, Willow holds the egg and feels fire and strength flood her body. She breathes flame, melts the lock, and fights through the corridors without killing anyone.

Soldiers block the exit, so Willow grabs Bri and flies them out using the egg’s power. Torion, guided by Freya, waits with a ship and helps them flee.

Knowing the egg is too dangerous for anyone, they drop it into the Obsidian Sea.

Back in Ardmuir, Willow confronts Wexley, steals The Oxblood Book from his shelves, and memorizes its spell. Wexley catches her, admits he poisoned Willow’s father and stole her mother’s mourning ring, and tries to seize control again.

Willow’s newly awakened magic burns him, and Bri and Finlay arrive in time to pull her away.

In the shop, Willow performs the anticurse on Bri, but nothing changes. The wolpertinger finally explains the truth: Bri isn’t cursed.

Her mother was a witch who once suppressed her own power to marry Bri’s Foundationalist father, and a spiteful man paid for a spell that partly freed that suppression while Bri was in the womb. Bri’s magic is real, just uncontrolled.

The wolpertinger also reveals Willow’s father used the Stokes family wish to suppress Willow’s own magic and keep her safe from Wexley. Offered a chance to restore her father, Willow refuses, choosing to move forward instead of rewriting the past.

Bri uses her remaining wish to fully remove her suppression and gain control of her witch power. Finlay spends his wish to heal his mother.

With Fromme’s confession, Wexley is arrested. His collection is auctioned, and Willow and Bri buy back key objects, including The Oxblood Book.

They reopen as partners, renaming the shop Stokes & Hargrave’s Cabinet of (Mostly) Magical Curiosities. Willow accepts her magic, Bri accepts her identity as a witch, and Finlay and Willow finally admit they love each other.

Together, the three build a new life in Ardmuir—one rooted in honesty, chosen family, and the strange, real magic they’ve learned to handle on their own terms.

Characters

Willow Stokes

Willow is the emotional and moral center of A Curious Kind of Magic: a young woman shaped by scarcity, disappointment, and a stubborn will to survive. Having inherited a shop built on her father’s scams, she begins the story cynical about magic and equally cynical about her own worth, convinced that she is only ever one missed rent payment away from ruin.

That desperation makes her sharp, pragmatic, and occasionally ruthless; she sees opportunity first because opportunity is what keeps her afloat. Yet what’s compelling about Willow is how quickly her hard edges reveal softer truths.

She’s lonely in a way she doesn’t want to admit, grieving a father she resents, and carrying a quiet ache for belonging. When real magic enters her world, it doesn’t simply offer profit, it forces her to confront what her father taught her about lying, hope, and survival.

Willow’s arc is a tug-of-war between exploitation and empathy: she wants to use Brianna’s touch to build a future, but she also grows fiercely protective of Brianna and Finlay, choosing them over safety more than once. Her awakening as a witch mirrors her internal awakening; the suppressed power in her becomes a metaphor for the self she has kept buried to avoid being hurt or targeted.

By the end, Willow becomes someone who can hold complexity without flinching—a businesswoman who tells the truth about temporary enchantments, a friend who risks everything to protect others, and a person who refuses the easy wish of resurrecting her father because she finally understands love isn’t possession.

Brianna Hargrave

Brianna arrives in Ardmuir like a storm held tightly inside a bottle—controlled on the surface, turbulent underneath. She is defined first by caution: wary of gifts, guarded about her mission, and determined not to let anyone close enough to get burned by her touch.

Her so-called curse isolates her physically and emotionally, and that isolation has trained her into self-reliance that can look like coldness. But Brianna’s restraint is not emptiness; it’s fear shaped by long experience of being treated as dangerous.

Her longing for the Hargrave grimoire is not only practical, it is existential—she wants a way to stop being a threat to the world and reclaim the right to be human among humans. Bri is also deeply principled.

Even when desperate, she worries about consequences, warns Willow against scheming, and tries to keep her magic from becoming a commodity. Her humor, once she trusts Willow, becomes a kind of rebellion against the story her parents forced on her.

The truth revealed later—that her power is not a curse but suppressed witchcraft misnamed to control her—reframes her entire life as gaslit survival. Her final wish to remove suppression and gain full control is not a grab for power but a reclamation of identity.

Brianna ends the novel more whole than she began: still scarred by parental rejection, but no longer defined by it, choosing community with Willow and Finlay and stepping into her witchhood as something she owns rather than endures.

Finlay Barrow

Finlay is the story’s quiet backbone: steady, local, warm-hearted, and far braver than his gentleness first suggests. He begins as Willow’s best friend and safe harbor, the person who shows up soaked by rain and still brings laughter with him.

His affection for Willow is obvious to the reader long before he allows himself to say it, and his love is expressed through service—cleaning her cottage, feeding Argyle, baking pies, worrying over her safety. What makes Finlay more than a supportive love interest is his moral clarity.

Unlike Willow, who is often tempted by shortcuts, Finlay consistently asks what the cost will be, who might get hurt, and whether magic’s return will attract predators. His concern isn’t cowardice, it’s caretaking born from his own vulnerability—especially his mother’s illness, which gives his hope a specific shape.

Finlay’s arc is about learning to stand beside Willow without being pushed to the margins of her fear. He doesn’t try to control her choices, but he refuses to be lied to when the stakes are life and death.

His Hargrave wish to heal his mother is a beautiful payoff because it shows his core nature: when handed the rarest kind of power, he uses it for love, not ambition. His reconciliation and romance with Willow feel earned because they grow out of years of trust rather than sudden chemistry, and when they finally confess love, it is the culmination of mutual recognition—two people choosing the same home in each other.

Oliver Wexley

Wexley is the novel’s embodiment of predatory greed dressed as civility. Introduced as a polished collector who restores order in Willow’s shop, he quickly becomes a reminder that power often enters rooms disguised as help.

Wexley understands systems—public opinion, intimidation, leverage—and uses them expertly. His interest in Willow is never about partnership; it is about control, and his charm is a weapon meant to make coercion look like opportunity.

He represents the dark underside of the magical trade that Willow’s father kept from her: a world where artifacts are stripped of meaning and people are treated as tools. His blackmail of Willow, threats toward her friends, and obsession with dragon relics reveal a man who believes entitlement is the same as destiny.

The later revelation that he poisoned Willow’s father and Alfred, stole her mother’s ring, and hunted Brianna’s lineage cements him as someone who has always confused ownership with mastery. Yet Wexley is also thematically important because he forces Willow’s growth; everything she becomes in resistance—honest, loyal, protective—happens because she sees what she could turn into if she followed his rules.

His downfall comes not from a single heroic blow but from exposure and confession, which suits him: a man who thrived in secrecy collapses when truth becomes unavoidable.

Torion

Torion begins as a shadow in a dockside deal, a Sapphire Islander trafficking in dragon bones, but he steadily complicates into one of the story’s most intriguing moral ambiguities. Unlike Wexley, Torion is not driven by pure domination; he is a trader who lives in a ruthless economy of magic, yet he shows consistent awareness of danger and consequence.

His willingness to rescue Willow and Brianna, and then to suggest destroying the dragon egg forever, shows that his relationship to power has a limit—a line he will not cross even if others do. He feels like someone shaped by the Sapphire Isles’ harsher magical culture, accustomed to bargaining with sacred things, but still capable of loyalty and ethical choice.

Torion also functions as a bridge between worlds: he knows the wider magical network, understands the Chancellor’s market, and later becomes part of the trio’s future adventures. By the end of A Curious Kind of Magic, Torion stands as a reminder that people raised in morally gray systems can still choose to act with decency, and that redemption can look like practical, grounded help rather than grand speeches.

Freya

Freya is a catalyst character—appearing briefly but altering the fate and self-understanding of the protagonists. She brings a witch’s certainty into a place of despair, naming Willow’s hidden magic outright and refusing Willow’s denial.

Freya’s calm urgency in Blackbay Prison shows both competence and compassion; she is not dazzled by dragon power, nor frightened by it, instead focusing on survival and responsibility. Her role suggests a larger magical community beyond Ardmuir, one that keeps watch and understands lineage and suppression.

Freya also embodies a theme the book returns to repeatedly: magic is not only wonder, it is identity, and denying it can be as damaging as misusing it. Though she is not present long, her belief in Willow gives Willow permission to believe in herself, and her alliance with Torion hints at networks of resistance to exploitative collectors like Wexley.

Mr. Tell

Mr. Tell, the grimoire conservator, is a portrait of gatekeeping that may come from fear, principle, or both. Surrounded by rare objects and protective of them, he initially seems like a cautious scholar, but his irritation and evasiveness when Brianna describes The Oxblood Book suggest he knows more than he admits.

He represents a recurring tension in the story: who gets to control access to magic and why. If he conceals information to prevent profiteering, he is morally understandable; if he does it to maintain power over knowledge, he becomes complicit in the same structures that endanger Bri.

His pet bat and guarded shelves underline his distance from ordinary people; he is a man more comfortable with artifacts than with messy human desperation. Whether cowardly or cautious, Mr. Tell’s refusal pushes Bri and Willow to stop relying on polite channels and start defining their own path.

Trystan Shilling

Trystan is the small-town bully upgraded by entitlement. He storms into the shoppe demanding proof not because he is curious but because he wants control of the narrative.

Trystan views Willow’s growing respectability as a challenge to the hierarchy that once kept her marginal, and his aggressive skepticism is a way to reassert dominance. His humiliation through the hair-loss pomade is more than a joke; it is symbolic reversal.

The world is shifting, magic is real, and the people he used to dismiss now have power he cannot ridicule away. Trystan functions as a social antagonist rather than a plot villain, showing how communities police “their place” until someone changes the rules.

Mrs. Shilling

Mrs. Shilling is a quieter reflection of Ardmuir’s social order. She arrives as a respectable customer seeking a birthday gift, embodying the town’s newly polite relationship with Willow now that Willow has something valuable.

Her willingness to accept the pomade without questioning its effect reveals a kind of complacent trust in tradition and status. She is not cruel like Trystan, but she benefits from a system that once mocked Willow’s shoppe.

Through her, the book shows how quickly public opinion can pivot when profit or novelty appears, and how social respectability often follows usefulness rather than fairness.

Mr. Granger

Mr. Granger, Willow’s landlord, represents blunt economic reality. He is not villainous in a melodramatic way; his pressure is the pressure of survival in a world where debt can erase you.

For Willow, he is the ticking clock that keeps her desperate and sometimes morally slippery. When she pays him with broom money, that act marks a turning point: she is no longer only surviving by her father’s old con artistry, but by something real, even if complicated.

Mr. Granger’s presence makes the stakes tangible—magic matters to Willow because rent matters, and rent is unforgiving.

Fromme

Fromme first appears as Wexley’s huge bodyguard, a symbol of intimidation that turns into a symbol of conscience. He is physically aligned with Wexley’s power, yet his eventual confession is what unravels Wexley’s empire.

Fromme suggests the cost of serving predators: he has likely witnessed enough cruelty to decide he wants out, and when he speaks, he chooses truth over loyalty. His arc is small on-page but meaningful in theme, showing that even those who seem like extensions of evil can reclaim agency.

Nora Monroe

Nora Monroe is mostly offstage, yet she matters as the owner of the dragon egg and the person Wexley wants robbed. She stands for a different kind of collector—someone who possesses extraordinary magic without turning it into an instrument of terror.

The fact that her egg is coveted because it promises immortality highlights how ownership of magic draws predators, and her role in the plot illustrates how Wexley’s reach extends far beyond Ardmuir. Even unseen, she helps define the moral spectrum of magical stewardship in the story.

Edward Stokes

Willow’s father is the ghost shaping almost every early choice she makes. As a swindler who stocked the shoppe with fake wonders, he left Willow both a livelihood and a legacy of distrust.

Yet he was not only a con man; his final wolpertinger wish to suppress Willow’s magic and keep her safe reveals a fierce, flawed love. His decision to hide the darker magical trade from her makes him complicated: protective in intention, damaging in consequence, because Willow grows up believing magic is only a lie and that her survival must come through deception.

Edward is a study in parental contradiction—someone who harmed through his choices but also sacrificed for his child. His refusal to be resurrected by Willow at the end is part of her growth, but also a quiet recognition of who he was: a man who loved imperfectly, and a love that still counts.

Argyle

Argyle, Willow’s kitten, is more than a cute companion; he is Willow’s first and most consistent source of uncomplicated attachment. In a life of debt, distrust, and shifting loyalties, Argyle provides steady comfort and a small domestic normalcy.

His presence also highlights Willow’s vulnerability: she speaks to him when she cannot speak to people, and his interruptions of emotionally dangerous moments underscore how fragile and precious those moments are.

Fergus

Fergus, Finlay’s borrowed horse, plays a practical supporting role in the plot, but he also quietly signifies trust between Finlay and Willow. Finlay lending Fergus to the journey is an act of support that costs him personally, reinforcing his reliability and willingness to shoulder burdens for people he loves.

Ivan and the Fisherman

Ivan and his grandfather appear briefly, yet they are key to Willow’s shift toward integrity. They are ordinary townsfolk who respond to magic with awe rather than exploitation.

Willow’s choice to honor her first offer and sell the broom to them, even when a richer trader appears, is a moral milestone. Through them, the book contrasts simple wonder with the collector market’s greed and shows Willow learning to value fairness over maximum profit.

Marcail

Marcail appears at the end as a mentor figure for Willow and Bri’s training in witchcraft. His presence signals transition from crisis to future: the girls are no longer improvising with half-understood power but stepping into intentional mastery.

Marcail represents the supportive magical adulthood neither girl had before—someone who teaches without exploiting, guiding them toward a life where magic is craft, not chaos.

Themes

Truth, Deception, and the Cost of Selling Illusions

Willow’s entire life at the start of A Curious Kind of Magic is built on performance. Edward Stokes’s shop is a monument to clever fraud: fake charms, staged wonders, and a reputation that depends on customers wanting to believe.

Willow inherits not only inventory but also a philosophy—her father’s idea that people buy dreams more than objects. That mindset has kept her afloat, yet it hollows out her sense of self.

She is both victim and accomplice of deception: ashamed of the lies, but also reliant on them to survive. The arrival of real magic destabilizes this arrangement.

Once Bri awakens the broom and the lamp, Willow is forced to confront a sharper moral equation. A fake trinket sold as a fantasy is one thing; a real magical item that fades in a day is another, because it turns wonder into a countdown.

Willow’s guilt after selling the broom shows she understands the difference, even while she tries to excuse it with old logic. The theme deepens when Wexley appears, embodying a more predatory version of the same trade.

He doesn’t sell gentle fantasies; he hoards power and uses deception as leverage. His blackmail of Willow echoes her father’s cons, but weaponized: lies that ruin lives rather than merely disappoint wallets.

The story keeps asking what honesty means in a world where magic itself can be rare, unstable, and tempting. Bri’s family calling her power a curse is another kind of deception—one meant to control rather than profit.

By the end, truth becomes a form of liberation. The wolpertinger’s explanations expose hidden histories that reset the characters’ identities.

Willow stops clinging to her father’s rationalizations and chooses transparency with customers and partners. Bri learns that what she called a curse was a distorted story told about her body and inheritance.

Even Wexley’s empire collapses once the truth moves from private threat into public consequence. The book suggests that deception may begin as survival, but it grows corrosive when it replaces real relationships.

Wonder still has value, but only when it isn’t built on someone else’s exploitation.

Power as Responsibility, Not Possession

Magic enters the story first as a promise of wealth and autonomy. For Willow, real enchantment looks like the answer to rent, hunger, and the fear of losing her home.

She imagines power primarily as something to sell or control. Bri, meanwhile, experiences power as something that controls her.

Her touch awakens dormant magic against her will, and because she cannot fully predict outcomes, every interaction carries risk. These opposing relationships to power collide and reshape both girls.

The broom episode is the clearest early lesson: a single awakened item changes Willow’s finances overnight, but it also attracts attention that quickly turns dangerous. The crowds lining up outside her shoppe show how power multiplies desire in others; the midnight dock deal shows how it also multiplies predators.

Wexley’s obsession with dragon relics pushes the theme into sharper focus. He treats magic as property, a ladder to immortality and dominance.

His collection is less about curiosity than conquest, and his willingness to sacrifice others—Willow, Bri, even Willow’s father—reveals the logical end of that worldview.

Willow’s forced theft mission shows her recognizing, in real time, that power taken without consent is poison. She doesn’t want the fossilized dragon egg for herself, nor does she want Wexley to have it, but the threat to her friends corners her.

When Willow finally uses the egg in prison, the scene flips the premise: power is not glamorous there, it is terrifying. She feels fire in her body, speed in her limbs, a capacity for violence that she must restrain.

Her decision to use flame to escape without killing guards marks her first mature engagement with power as responsibility. The choice to discard the egg into the sea seals the theme.

She and Bri understand that some power should not be owned by anyone, not even “good” people. Bri’s final wish follows the same logic.

She doesn’t wish away her magic or hand it to someone else; she wishes for control so she can live ethically with it. Finlay’s wish to heal his mother contrasts with Wexley’s hunger for immortality, giving another angle on power’s purpose.

The story lands on a clear ethic: power is meaningful only when tied to care, restraint, and shared trust. Possession for its own sake leads to paranoia and cruelty; responsibility leads to freedom.

Identity, Inheritance, and Reclaiming the Self

Both Willow and Bri begin the book living under inherited stories that define them. Willow is “the swindler’s daughter,” a role that shapes how town gossip sees her and how she sees herself.

She has internalized the idea that her father’s shadow is permanent, that she is expected to be cunning, lonely, and a little untrustworthy. Even her refusal of Finlay’s care after her trip speaks to this identity cage: she fears dependence because it would make her vulnerable to being judged or abandoned.

Bri carries a different inherited burden. Her family’s narrative frames her magic as contamination.

The word “curse” becomes a label that erases her agency and turns her own body into a threat. She has spent years believing that her natural state makes her unlovable, and this belief is reinforced by her parents’ fear and ultimatum.

Their friendship becomes the main arena where identity is renegotiated. Willow discovers that Bri is not merely a means to profit but a person with grief, tenderness, and terror.

Bri discovers that Willow’s bluntness covers a deep craving for belonging. Their shared routines—inventory mornings, pastries, violin in the rain—build a home that neither of them has fully had.

The truth about their bloodlines shifts everything. Bri learns her power is not a random punishment but a broken inheritance from a mother who had to hide herself to survive marriage.

That revelation reframes Bri’s entire childhood. She is not defective; she is unfinished, a witch without training because the adults who should have guided her were trapped in fear.

Willow’s revelation is equally seismic. Her father’s wolpertinger wish suppressed her magic, meaning her “ordinary” identity was a kind of enforced disguise.

At first, this feels like another theft—another life decision made for her. Yet it also clarifies why she has always felt out of place in her father’s world.

She was never meant only to sell magic; she was meant to live it.

Reclaiming identity, then, is not a simple return to roots but a conscious choice about what to keep and what to reject. Bri chooses to stay in Ardmuir despite her parents’ rejection, building kinship from friends rather than blood approval.

Willow refuses the wolpertinger’s offer to bring her father back, indicating that she will not define herself through his presence any longer. Their partnership in the renewed shoppe signals that inheritance can be transformed.

They take what is useful—skill, knowledge, tradition—but refuse the shame and secrecy that came with it. The book presents identity as something that may start in family history, but becomes real only when the person living it decides its meaning.

Love, Trust, and Respecting Boundaries

The relationships in A Curious Kind of Magic are built less on grand declarations and more on the slow work of trust. Willow and Finlay’s bond demonstrates this from the beginning.

Finlay’s steady kindness—showing up in rain, cleaning her cottage, baking for appointments—contrasts with Willow’s guarded instinct to handle everything alone. Her resistance is not cruelty so much as fear shaped by years of hardship and her father’s unreliable legacy.

The tension between them shows love as something that must be learned, especially by someone who equates need with danger. Their near-kisses and interrupted moments are not melodrama; they show two people navigating vulnerability with imperfect timing.

With Bri, trust is tested more explicitly through boundaries. Bri’s refusal of physical contact is one of the most emotionally charged limits in the story.

It is easy for Willow to misunderstand it at first as rejection, but the insect-swarm incident makes its stakes undeniable. Bri’s boundary is not preference; it is survival, both for others and for her fragile control over herself.

The scene forces Willow to confront the difference between wanting closeness and earning permission. Their later agreement—respect without resentment—is a turning point in how the book frames care.

Love cannot be measured by how much access you get to someone’s body or secrets. It is measured by how seriously you take their “no.”

Even the antagonistic relationship with Wexley reveals a warped version of trust. He counts on Willow’s desperation, her loyalty to friends, and her need for safety to manipulate her.

His threats show what trust becomes when stripped of respect: a tool for coercion. The contrast helps highlight the healthier forms of trust elsewhere.

Bri trusting Willow enough to say yes in prison, enough to accept a home, enough to let Willow attempt the anticurse, marks her growth from fear to relationship. Willow trusting Bri with the shoppe, trusting Finlay with her terror, and eventually trusting herself as a magic-holder completes the arc.

The ending makes this theme concrete. Bri’s decision to wish for full witch powers is also a decision to stop living as someone else’s risk.

She chooses a future where she can love without constant fear of harm. Willow and Finlay’s reconciliation comes only after honesty is restored; affection follows responsibility, not the other way around.

The friendships and romance that remain at the end are not based on ignoring limits, but on listening to them until they become part of daily life. The book treats love as a practice: showing up, telling the truth, and making space for another person’s autonomy.

Home, Belonging, and Chosen Family

Ardmuir begins as a place Willow endures rather than inhabits. Her shoppe is more a burden than a sanctuary, tied to debt and to her father’s reputation.

Her cottage is quiet to the point of ache. The first half of the story keeps returning to images of emptiness: rent notices, meals alone, evenings with only a kitten for company.

What changes this is not simply the arrival of magic, but the arrival of people who stay. Bri’s move into Willow’s cottage marks a shift from isolation to shared life.

Their home becomes a working base, a refuge, and a space where silence is no longer loneliness but comfort. Finlay’s constant presence supports the same transformation.

His pies, his repairs, his gentle arguments about safety all act like small bricks in a house that didn’t exist before.

Belonging is also complicated by origin. Bri comes from across the sea, and her return to Achnarach is filled with secrecy and hurt.

She is technically “from” here, yet she doesn’t belong in the way she hoped because her family has built a wall around her. Willow is “from” Ardmuir in every public sense, but her social standing is fragile, marked by the Stokes name and by poverty.

The book shows that birthplace is not the same as belonging. Belonging requires being known without being punished for who you are.

Bri doesn’t find that with her parents. She finds it in a cottage with mismatched routines, a shop that tells the truth about temporary magic, and two friends who accept her limits.

The wolpertinger’s final departure underscores the theme. Wishes and old family bargains are not what ultimately create home.

The real home is the one the characters build after magic has threatened to tear them apart. Willow refusing her father’s restoration is not just grief; it is commitment to the living community she has now.

Bri staying in Ardmuir after her parents’ rejection is not resignation; it is a deliberate choice of a safer, truer belonging. Finlay’s wish to heal his mother ties him again to his roots, but his fully realized future still includes Willow and Bri.

Their reopening of the shoppe as Stokes & Hargrave’s Cabinet of (Mostly) Magical Curiosities is a public declaration that home can be remade. Not inherited intact, not granted by bloodlines or town approval, but claimed by people who decide to care for one another.

The book closes on a vision of belonging that is practical and earned: shared work, shared risks, shared laughter, and a space that is finally theirs.