A Merry Little Lie Summary, Characters and Themes

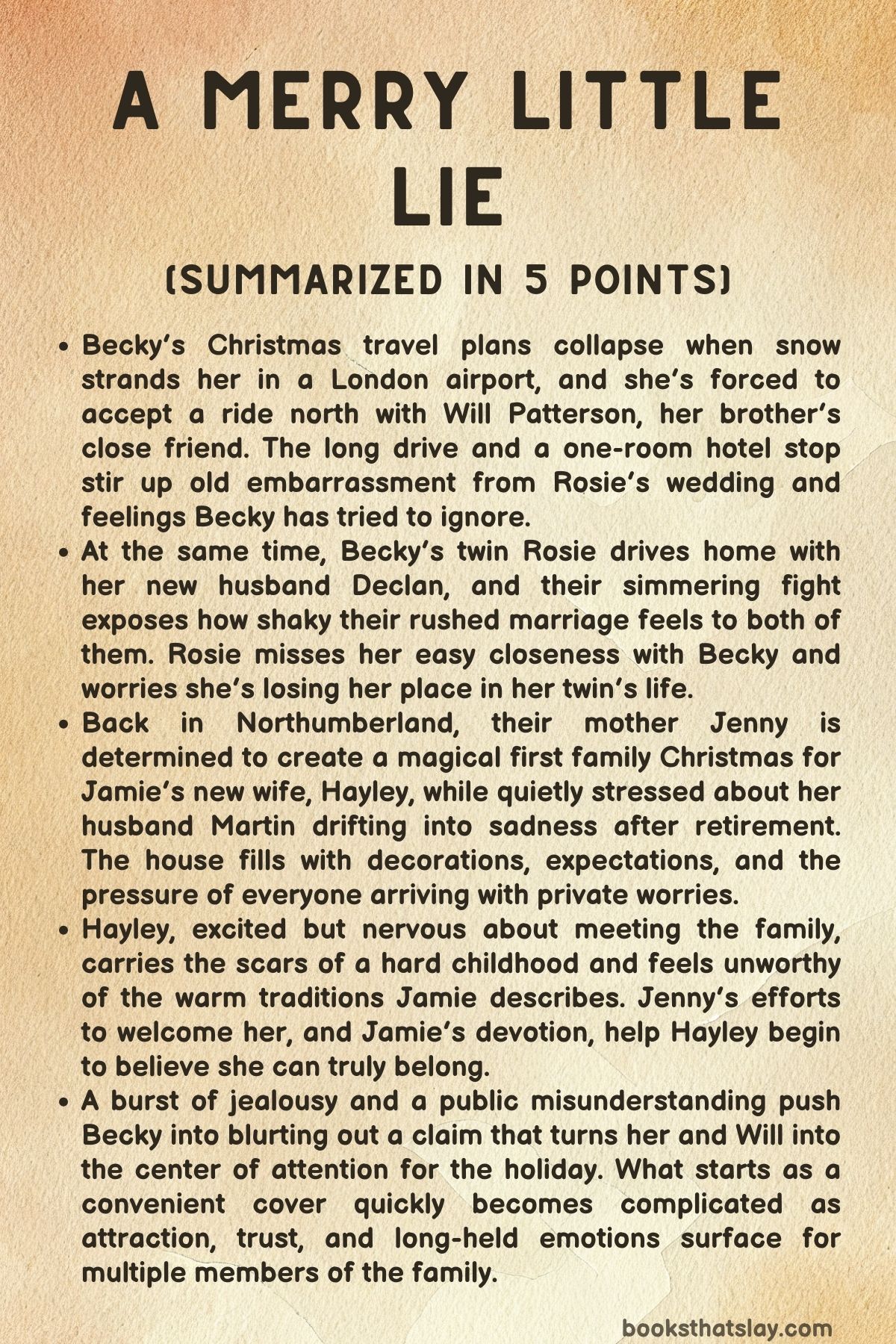

A Merry Little Lie by Sarah Morgan is a contemporary holiday romance set around a snowbound Christmas in Northumberland. The story follows three women in the same family—twin sisters Becky and Rosie, and their mother Jenny—each carrying quiet fears about love, belonging, and change.

When travel chaos forces Becky to share a long drive (and later a hotel room) with Will, her brother’s best friend, an impulsive lie turns into something neither of them expected. At the same time, Rosie’s new marriage wobbles under insecurity, and Jenny tries to hold her family together while worrying about her husband’s shaky retirement. It’s a warm, funny, family-centered romance about honesty, second chances, and the messy ways people find home.

Summary

Becky is stranded in a packed London airport a few days before Christmas, watching the departures board fill with cancellations as heavy snow shuts down flights. She needs to get back to Northumberland for her family holiday and for a party her brother Jamie is throwing for a “big announcement.” With trains on strike and rental cars disappearing fast, Becky briefly considers staying in London.

Family gatherings have felt harder lately—especially since her twin sister Rosie married Declan and their once effortless closeness has shifted. But memories of her mother’s rituals and the pull of home win out.

She heads to the car-rental line, already tense about facing a holiday where Rosie will arrive with her husband and Jamie with a new girlfriend, while Becky feels stuck, single, and unsure of her place.

In the queue Becky bumps into Will Patterson, Jamie’s lifelong best friend and a cardiologist she’s known since childhood. Their relationship is awkward after a humiliating moment at Rosie’s wedding that Becky refuses to think about.

Will notices she’s rattled and offers to drive her north in his own car. Becky pushes back, insisting she needs independence and privacy for work calls, but before she can decline fully, they hear the desks announce there are no cars left.

With no other way home, she accepts. They leave together into worsening weather, trying for light conversation while both sense the trip will be long, uncomfortable, and emotionally loaded.

Meanwhile Rosie sits in a freezing car in London with her husband Declan, their silence thick after a fight. The argument began when Rosie skipped Declan’s work Christmas party; he felt embarrassed going alone and hurt she didn’t support him, while she felt out of place and judged among his colleagues.

Rosie’s doubts spiral. She rushed their relationship forward—moving in quickly, proposing impulsively—and now fears she may have mistaken momentum for certainty.

On top of that she misses Becky, who has been distant for months, and worries their twin bond is slipping away just when Rosie needs it most. As they start their snowy drive north, the hurt between them stays close to the surface.

Back in Northumberland, their mother Jenny is preparing Mill House for Christmas with the anxious energy of someone trying to keep everything perfect. Her husband Martin retired from being a family doctor two months ago and has become quiet, withdrawn, and uninterested in daily life.

Jenny is frightened by how lost he seems, but she hides her worry behind lists and decorations. The upcoming party adds pressure: Jamie has been cryptic about his “big announcement,” and Jenny assumes he plans to propose to Hayley, a new girlfriend of only a few months.

She wants the house to look magical for Hayley’s first family holiday, even as she feels her own foundations wobbling.

Jamie and Hayley drive through the snowy countryside toward Mill House. Hayley is excited by the landscape, but nervous about meeting Jamie’s family and about the secret she and Jamie are carrying.

Her childhood in care left her expecting rejection, and she is terrified of doing something wrong. Jamie tries to reassure her by describing his family’s warm Christmas traditions—stockings by the fire, building toys together, noisy breakfasts.

Hayley admits her own Christmas memories are sparse and practical, shaped by donations rather than celebration. Jamie is moved and promises to give her the kind of Christmas she never had.

Their secret, however, is bigger than Jenny suspects: Jamie and Hayley are already married, and the party is meant to be their reveal.

Becky and Will’s drive turns into an overnight stop when accidents and bad roads slow them down. At a crowded hotel they discover only one room remains, an attic space with a single bed.

Will lies to both their mothers to avoid gossip, and Becky tries to treat the situation like a joke, even while her nerves spike. Dinner by a fire and shared desserts blur the line between teasing and attraction.

Becky keeps telling herself she isn’t that kind of person, that emotions are messy and irrational, and that love already complicated her life once before. Yet in the tiny room, with Will easy and close, her defenses start to slip.

The next day the family gathers at Mill House. Preparations for the party are in full swing as Jenny, Rosie, Hayley, and Jenny’s mother Phyllis cook and decorate.

Jenny notices Martin disappearing to hide upstairs, listening to podcasts about surviving retirement, and realizes he is struggling more than he admits. She gently pushes him to rejoin the family.

Rosie tries to act cheerful, but she’s exhausted by the drive and unsettled by how often Declan and Becky fall into easy laughter. When Becky arrives with Will, Rosie’s insecurity spikes into a rash, public accusation that Becky is in love with Declan.

Becky is stunned and, in a panic to protect Rosie and shut the moment down, blurts out a different claim: she’s in love with Will.

The room freezes, then erupts into delighted shock. Everyone assumes Becky and Will have been secretly together.

Will, reading Becky’s distress, backs her up without hesitation. Outside, Becky admits the truth: she lied to stop Rosie’s spiral and wants to correct it.

Will argues that taking it back now will only reignite Rosie’s fears. He suggests they pretend to be a couple through Christmas, then quietly “break up” later.

Becky hates the idea but sees no clean exit. To sell the story, Will pulls her close and kisses her.

Becky is startled by how real it feels, and by how hard it is to separate performance from desire.

Rosie soon regrets her outburst. She and Declan talk privately, and Rosie admits her jealousy comes from feeling useless next to Becky’s confidence and shared history with Declan.

Declan assures her he chose Rosie for who she is, not for a checklist of compatibility. Their conversation doesn’t solve everything instantly, but it steadies them.

Rosie also senses that Becky’s distance has deeper roots than Declan, though she doesn’t yet know what.

When Christmas Eve arrives, Jenny finally has a quiet moment with Jamie. He confesses that he and Hayley married in secret and apologizes for the drama of the delayed reveal.

Jenny forgives him and reassures him she loves Hayley, even if she needed time to adjust. Later Hayley finds Jenny’s hidden list titled “Perfect Christmas for Hayley.” Instead of feeling patronized, she’s touched by how hard Jenny tried to make her feel wanted.

The two share a sincere, healing conversation that cements Hayley’s place in the family.

Outside in the snow, Becky pulls Rosie aside and breaks down. She admits the relationship with Will began as a pretend couple act, but became real overnight.

She also confesses what happened at Rosie’s wedding: she panicked about losing her twin as her “number one person,” misread her grief as romantic feelings for Declan, and fled in shame. Will found her, listened, and helped her understand that her fear was about Rosie, not Declan.

Becky withdrew afterward, changed jobs impulsively, and carried months of guilt. Rosie is shocked, then relieved.

She admits she has had her own doubts about marriage and about Becky growing away from her. The sisters reaffirm their bond, softer and more honest than before.

Becky tries to go back to pretending in front of the family, but Will refuses to treat their night together as a fluke. On a beach walk he confronts her gently and admits he has loved her for years.

Becky finally lets herself say it back. Will reveals he bought a ring long ago, waiting for a moment when she might be ready.

He proposes on the shore, and Becky says yes, stunned and joyful. The family, watching from the house, celebrates the engagement.

Christmas Day arrives with the usual chaos—stockings, food, teasing, and laughter now threaded with new promises. Martin gives Jenny a playful “Worry Box” for her anxieties and plans a winter trip for them, signaling he is ready to find a new direction.

Hayley lies awake that night under the glow of the decorations, thinking about how imperfect and welcoming this Christmas has been. She nudges Jamie awake and starts to speak, hinting that another surprise may be on the way.

Characters

Becky

Becky is the story’s emotional anchor and the character most defined by inner contradiction: she is brilliant, pragmatic, and independent to the point of self-protection, yet quietly hungry for belonging and love. In A Merry Little Lie, she moves through life as a systems-thinker, someone who trusts logic, engineering, and competence more than feelings, which is why social situations and romantic vulnerability feel to her like unpredictable variables.

Her dread of returning home isn’t rooted in dislike of family but in fear of change—Rosie’s marriage has destabilized Becky’s sense of “twinhood” as her primary relationship, leaving her feeling displaced and lonely in ways she can’t quite name. That unprocessed grief misfires into anxiety about romance and rejection, and she responds by withdrawing, switching jobs impulsively, and trying to control distance rather than confront emotion.

What makes Becky compelling is that her arc isn’t about becoming a different person; it’s about recognizing that her emotional life is not illogical or shameful. Will’s steady presence gives her a safe mirror, and the forced “fake relationship” becomes the pressure-cooker that finally breaks her avoidance.

By the time she accepts Will’s love and her own, Becky hasn’t been “fixed” by romance—she has reclaimed her ability to trust herself, admit what she feels, and stop managing her life around what might hurt other people.

Will Patterson

Will is a quietly intense counterweight to Becky’s guardedness, a man whose calm competence masks long-held devotion. As Jamie’s lifelong best friend and a cardiologist, he embodies responsibility and steadiness, but A Merry Little Lie shows that his emotional courage is just as significant as his professional one.

He has loved Becky for years without pushing himself into her life, which suggests both patience and restraint, and he understands her better than she understands herself. Will is perceptive enough to notice her unhappiness in London, gentle enough not to pry when she resists, and bold enough to step in when she needs help even if she insists she doesn’t.

The “one bed” night and subsequent pretend romance reveal how he balances respect with desire—he never manipulates her, but once the door opens, he refuses to retreat into pretense. His proposal isn’t impulsive holiday spectacle; it is the culmination of years of quiet certainty symbolized by the ring he already bought.

Will’s role in the novel is not to rescue Becky but to hold steady until she can meet him in the same emotional reality, making him one of the book’s most grounded and tender figures.

Rosie

Rosie is the outwardly warm twin whose confidence hides deep vulnerability, particularly around worth and belonging. In A Merry Little Lie, Rosie has always been the social bridge for Becky, the one fluent in emotions, friendships, and performances of ease, which makes her upheaval after marriage especially striking.

She pushes love fast—dating, moving in, proposing—because speed feels like security to her, yet that same speed leaves her terrified she may have built her life on a mistake. Her fight with Declan exposes a core insecurity: she fears being seen as lesser, especially in spaces where she doesn’t understand the “rules,” like Declan’s workplace, and she internalizes imagined judgment quickly.

This anxiety then mutates into jealousy toward Becky, not because she doubts Becky’s integrity, but because Rosie has lived a lifetime beside someone who shares her face and history; any shift in that bond feels existential. Her public accusation is ugly but human—it’s a panic flare from someone terrified of losing both her marriage and her twin.

Rosie’s growth comes through humility and reconnection: she apologizes, listens, and finally names the truth that she still needs Becky as her “number one” person in a way marriage can’t replace. By the end, Rosie isn’t magically secure, but she is more honest, more communicative, and less ruled by fear.

Declan

Declan is the novel’s portrait of a good man learning emotional literacy at the speed of someone else’s pain. Within A Merry Little Lie, he is methodical, controlled, and rooted in practical logic—traits that serve him professionally but create friction in an intimate relationship with a partner who craves reassurance and emotional presence.

His irritation at Rosie’s packing or lack of structure isn’t cruelty; it’s a reflex toward order that he mistakes for helpfulness. When conflict arises, Declan’s instinct is to postpone, calm, and compartmentalize, which Rosie experiences as rejection because her style is to confront and feel immediately.

That mismatch is the heart of their struggle. Yet Declan consistently shows he is invested: he drives through dangerous snow, he admits embarrassment about attending the party alone, and he firmly denies any romantic interest in Becky when Rosie spirals.

His tenderness surfaces in quiet moments—agreeing Rosie is extraordinary under Phyllis’s prompting, offering to talk after noticing her absence, staying engaged even when hurt. Declan’s arc is not about dramatic transformation but about learning to translate love into the language Rosie can hear, and in doing so he becomes a believable, imperfect, fundamentally caring partner.

Jamie

Jamie is the family’s kinetic force, warmhearted and enthusiastic, but also impulsive enough to create chaos without fully seeing it. In A Merry Little Lie, he is the sibling around whom everyone else’s anxieties orbit: Becky fears another sudden engagement, Rosie feels destabilized by his new life, and Jenny worries about holding the household together under the pressure of his big surprise.

Jamie’s secret marriage to Hayley reveals both devotion and a blind spot—he protects Hayley by keeping things small, yet he underestimates how secrecy will stress his mother and isolate Hayley in a new family. Still, his emotional instincts are largely kind.

He is sensitive to Hayley’s past in care, deeply moved by her story, and determined to build for her the kind of Christmas she never had. Jamie is also a connector, the one who treats Will as family and whose friendships anchor the wider community around Mill House.

He grows through accountability rather than shame: he apologizes to Jenny, learns to stay beside Hayley socially, and embraces a future shaped by partnership rather than performance. His optimism is genuine, and the novel uses him to show how love can be both clumsy and sincere at once.

Hayley

Hayley embodies the theme of chosen family and the fear of not deserving it. In A Merry Little Lie, her excitement about Christmas is layered over a childhood of deprivation and instability, where holidays meant practical hand-me-downs and no sense of permanence.

That history leaves her hypervigilant about rejection: she memorizes family facts, worries about doing the wrong thing, and reads small cues as potential threats. At the same time, she is adventurous and openhearted, drawn to landscapes, traditions, and experiences she never had the chance to claim as “hers.” Her love for Jamie is sincere but also a refuge, which is why the secret marriage feels both romantic and risky—she wants security, but fears being a burden.

Hayley’s most moving moments are her quiet ones: feeling guilty while everyone cooks, worrying Jenny is less joyful about her marriage, and being stunned to discover the “Perfect Christmas for Hayley” list. When she sees Jenny’s effort not as pressure but as love, Hayley allows herself to believe she can belong without earning it through perfection.

By the end she recognizes that real family isn’t flawless or movie-like; it’s messy, attentive, and willing to meet you where your scars live.

Jennifer (Jenny)

Jenny is the emotional manager of the household, a woman who expresses love through preparation, tradition, and labor. In A Merry Little Lie, she is caught between generations—still a daughter caring for elderly parents, a wife worried for a drifting husband, and a mother trying to hold space for children whose adult lives are changing fast.

Jenny’s desire to engineer a “perfect” Christmas for Hayley isn’t superficial; it’s her attempt to create safety and welcome, especially for someone she fears might feel out of place. Yet that drive for perfection reveals Jenny’s deeper anxiety: she believes harmony depends on her constant effort, and any crack in the family is her responsibility to patch.

Martin’s withdrawal after retirement terrifies her because she can’t solve it with lists or decorations. Her arc is about learning that care also means letting others carry weight.

She begins to see Martin’s struggle not as laziness but grief for his lost purpose, and she chooses empathy over resentment. When she decides to play along with Becky and Will’s lie, it’s another act of protective love, but tempered by wiser flexibility.

Jenny ends the story still a worrier, but more supported, more seen, and more able to accept an imperfect holiday as a successful one.

Martin

Martin represents the silent crisis of identity loss that can follow retirement, especially for someone whose life was built around being needed. In A Merry Little Lie, he begins as a shadow in the house—pajamas, daytime television, avoidance—creating unease not because he is unkind, but because he seems absent from himself.

His admission that retirement makes him feel old and purposeless reframes his behavior as depression-like drift rather than stubbornness. The podcast about surviving retirement is a key detail: Martin is not refusing life; he is searching for a way to re-enter it without the role that once defined him.

His family’s bustling Christmas preparations contrast with his inertia, heightening his shame and isolation. But Martin is capable of tenderness and imagination when he is re-engaged, evidenced by the “Worry Box” gift for Jenny and the January trip he plans to soften the post-holiday emptiness.

His arc is gentle but meaningful: he moves from hiding to participating, from being cared for to caring again, showing that purpose can be rebuilt, not replaced.

Phyllis

Phyllis, Jenny’s mother, is the classic family matriarch with sharp eyes and sharper commentary, serving both humor and truth. In A Merry Little Lie, she operates as a kind of emotional detective: she notices Rosie’s forced cheer, clocks Becky and Will’s chemistry, and even remembers childhood patterns that hint at Becky’s previous cover-ups.

Her gossiping and boundary-skating are real flaws, but they come from engagement rather than malice—Phyllis loves her family fiercely and expresses it through attention and intrusion. She also offers direct affirmation, praising Rosie’s talent and pressing Declan to name Rosie’s value, which becomes a healing moment.

Phyllis’s role is to keep the emotional temperature honest: she doesn’t let people hide behind politeness, and even when she embarrasses Jenny, she nudges the family toward recognizing what’s already true.

Audrey Patterson

Audrey, Will’s mother, appears briefly but vividly as the warm, matchmaking, community-minded parent archetype. In A Merry Little Lie, her immediate romantic speculation about Becky and Will, while comic, also signals how long the older generation has sensed the possibility between them.

Audrey’s enthusiasm amplifies the social pressure that traps Becky in the lie, but not from manipulation—she’s acting from affectionate excitement and genuine belief that these two belong together. She represents the friendly, slightly intrusive village network that surrounds the family, making romance feel both private and publicly cherished.

Elsie

Elsie is mostly offstage, yet her presence matters as part of Will’s emotional history. In A Merry Little Lie, she functions as a contrast that clarifies Will’s heart: even his former partner recognized that his deepest feelings were for Becky.

Elsie is not used as a rival villain; instead she is evidence of Will’s long-standing, quiet truth. Her role reinforces the idea that Will’s love is not a holiday whim but something rooted and enduring.

Percy

Percy, the family’s English setter, is more than background charm; he is a small symbol of continuity and home. In A Merry Little Lie, Percy’s special rules and predictable behavior reinforce the family’s shared history and rituals.

His barking at Becky and Will’s arrival punctuates the moment when the lie detonates into real change, almost like the household itself announcing that the story has shifted. Percy represents uncomplicated belonging—he loves the family without conditions, mirroring what the human characters are struggling to trust.

Themes

Family bonds under pressure and renewal

Holiday time in A Merry Little Lie functions like a stress test for family ties that have quietly frayed. Becky’s dread of going home is not about a single conflict; it comes from sensing that the family she once knew is shifting into something she hasn’t learned how to stand inside.

Rosie’s marriage rearranges the twin dynamic that used to anchor Becky’s daily life, and that loss is experienced like grief even though nobody has died. The story keeps returning to small, concrete markers of belonging — stockings by the fireplace, shared breakfast rituals, a dog with house rules — to show how family identity is built through repeated acts, not speeches.

When new partners arrive, those rituals wobble. Jenny tries to compensate by manufacturing an idealized celebration, and her effort reveals a parent’s fear that love might not be enough to keep everyone feeling safe.

The family’s warmth is real, but it is also work, and the novel doesn’t sentimentalize that.

What restores the bonds is not perfection but honesty. Becky’s eventual confession to Rosie reframes months of distance as a panicked response to change rather than rejection, allowing the sisters to re-enter each other’s lives without shame.

Jamie’s quiet apology to Jenny likewise resets their relationship; he acknowledges the unintended harm of secrecy, and she chooses welcome over punishment. Even Martin’s retreat is folded into this theme: the family has to learn that care can mean noticing someone’s withdrawal and inviting them back without humiliation.

By the end, the household is not the same as it was in childhood, and the book treats that as both inevitable and survivable. Family love here is shown as flexible enough to include new spouses, new fears, and new versions of each person, provided they keep turning toward one another instead of away.

Love, fear, and the cost of pretending

A lie sits at the center of the plot, but the novel is less interested in deception as a moral failure than as a survival tactic people use when they’re scared. Becky blurts out the fake relationship with Will to stop Rosie’s accusation, and the family’s quick acceptance shows how eager they are to believe in neat romantic narratives.

The awkward comedy of pretending to be a couple exposes a more serious question: what happens when someone agrees to a story about themselves because telling the truth feels too risky? For Becky, the lie grants temporary safety inside her family’s expectations, but it also traps her in constant self-monitoring.

She is forced to perform feelings she does not yet understand, and that performance becomes a mirror that reveals feelings she has been refusing to name.

The theme works in parallel with Rosie and Declan. Their conflict grows not from the fact that they married quickly, but from the way they avoid their real insecurities.

Rosie fears she does not belong in Declan’s world and hears judgment in every silence. Declan fears being unsupported and hides that fear behind irritation.

Both are, in their own way, pretending to be fine until the pretending becomes unbearable. Jamie and Hayley add another layer: their secret marriage begins as protection for Hayley’s anxieties, yet it inadvertently creates new anxiety for Jenny and reinforces Hayley’s sense that she must earn acceptance through secrecy.

When love finally becomes real in the open, it is because the characters stop using performance as armor. Will’s confession that he has loved Becky for years breaks the false story and replaces it with a riskier truth.

The book’s stance is clear: fear-based pretending may buy time, but lasting intimacy requires choosing honesty even when the outcome isn’t guaranteed. The romantic resolution is therefore not just about a couple getting together, but about a person learning that love cannot grow inside a disguise.

Identity, self-worth, and finding a place in other people’s worlds

The novel keeps placing characters in rooms where they feel slightly out of place: Becky at her new job’s forced social culture, Rosie among Declan’s colleagues, Hayley in a family Christmas she has never experienced, Martin in a life after medicine. Each situation asks the same question from a different angle: who am I when the role I’m used to no longer fits?

Becky’s confidence in engineering contrasts sharply with her uncertainty in emotional spaces. She has built her identity on competence, logic, and independence, so romance and family change feel like territories where she lacks a map.

Rosie’s identity is tied to being the socially fluent twin and the artistic caretaker, but marriage confronts her with the fear that skill and warmth don’t automatically translate into belonging in Declan’s professional environment. Her jealousy around Becky is fueled by an old wound of comparison, not by any real betrayal.

Hayley’s arc makes the theme explicit through her childhood in care. She learned to expect rejection and to treat fitting in as a task that must be performed correctly.

Her careful memorizing of facts about Jamie’s family shows both her determination and her fear. The family’s traditions are new to her, and she reads them as tests of whether she deserves to stay.

Jenny, meanwhile, defines herself as the one who holds Christmas together, and that self-image becomes shaky when she cannot rely on Martin’s steady partnership or predict her children’s choices. Martin’s retirement is the starkest version of identity loss; after decades as a doctor, he faces a quiet house and wonders if he still matters.

Across these stories, self-worth is rebuilt through acceptance that isn’t conditional on performance. Rosie learns that Declan’s love isn’t contingent on her matching his world.

Hayley learns she can be welcomed without earning it through flawless behavior. Becky learns that being loved does not require her to become a different kind of person, only a more honest one.

Martin learns that usefulness can take new forms. The theme frames identity as something that must be renegotiated in every life transition, with family and partners acting as both the challenge and the support.

Belonging, chosen traditions, and the meaning of home

Snow, travel delays, and long drives are more than plot devices; they create a contrast between the instability outside and the idea of home as a desired refuge. Characters keep circling what “home” means.

For Becky, home is comfort mixed with dread — a place of cinnamon cookies and expectations, where love is certain but her place in the new arrangement feels uncertain. For Rosie, home is both Mill House and the pre-marriage closeness with Becky, and she experiences the move into married life as being slightly exiled from her original home.

Hayley’s understanding of home is the most fragile. Her childhood taught her that places are temporary and belonging can be withdrawn, so she approaches Mill House with excitement but also with a practiced readiness to be disappointed.

Traditions become a language for belonging. Jamie’s recollection of stockings and shared toys shows a childhood where home was made through playful sameness and reliable rituals.

Hayley’s memories of practical donations in care show a childhood where Christmas was about survival rather than affection. When Jenny makes a list to create a “perfect” holiday for Hayley, she is trying to translate love into a form Hayley can recognize.

The list is slightly misguided because it aims for cinema-level polish, but its motive is what matters: an adult choosing to build a home large enough for someone who has never had one. Hayley’s response reveals that home is not a fixed aesthetic; it is the feeling of being wanted even in the mess.

By the end, belonging is shown as a shared construction rather than a gift handed down intact. Becky and Will’s relationship, Rosie and Declan’s repair, Martin and Jenny’s new plans, and Hayley’s quiet relief after an imperfect but loving Christmas all point to the same conclusion.

Home is not just a place you return to; it is a set of relationships that keep re-choosing you, and that you keep re-choosing in return.