A Scar in the Bone Summary, Characters and Themes

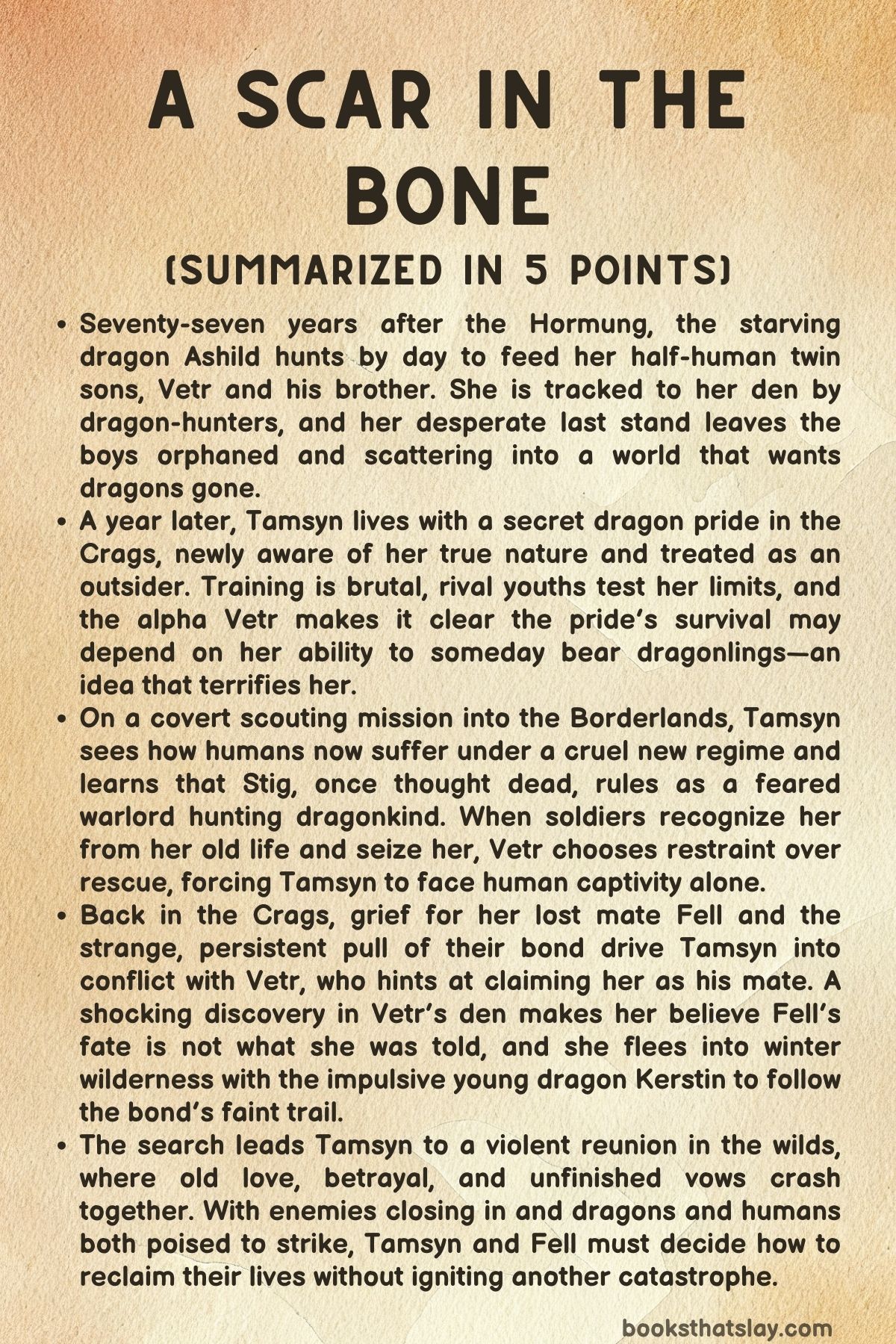

A Scar in the Bone by Sophie Jordan is a romantasy set in a harsh, post-war North where dragons hide in human form to survive. The story follows Tamsyn, a young woman raised as human who discovers she is dragon-born and is pulled between two worlds: a secret dragon pride in the Crags and the brutal human politics of the Borderlands.

Grief, identity, and survival shape her choices as old bonds refuse to die and new ones threaten to form. With danger rising on every side, Tamsyn must decide what loyalty means— to her kind, her past, and the mate she refuses to forget.

Summary

Seventy-seven years after the Hormung, dragons are nearly extinct and hunted to scraps. Ashild, one of the last, flies through a red sky to find food for her twin sons.

She returns empty-clawed to a deep mountain den where her children—who look human to strangers—wait hungrily. The stores are almost gone.

Ashild thinks about seeking another pride for safety, but doing so would mean taking a new mate and breeding in service of rebuilding dragonkind. She cannot face that after losing Sigurd, her bondmate who vanished two years earlier.

Worse, she fears other dragons will reject her sons for their human appearance.

Before she can decide, humans invade her tunnels. A dozen men arrive led by a gray-bearded hunter carrying an axe carved from dragon bone.

They delight in finding a dragon they assumed no longer existed and gape at her hoard. Seeing the boys, the leader orders his men not to hurt them, believing they are human.

Ashild fights with everything she has, crushing two attackers outright, but starvation has left her too weak. The group swarms her with steel.

The leader drives the dragon-bone axe into her chest and takes a black opal chain from her neck, a gift from Sigurd. Ashild’s final act is to lock eyes with her sons, willing them to live.

The axe falls again, and she dies as the boys watch.

A year later, one of those survivors—Tamsyn—lives within a hidden dragon pride in the Crags. Raised among humans, she only recently learned her true nature.

The pride feeds and trains her, but distrust shadows every day. In the sparring arena she faces Nayden and Kerstin, youths who often join forces against her.

Nayden pins her and mocks her, and when she slips free and bests them both, he snaps and breathes fire in violation of the rules. The flame scorches Tamsyn’s hair and temple.

Vetr, the pride’s alpha and a powerful mist-shader, storms in and ends the bout. He punishes Nayden and defends Tamsyn, reminding everyone they must fight in human form to keep their secret.

Nayden points to the purple blood at Tamsyn’s mouth, saying she cannot fully control her shifting and is therefore useless. Vetr rejects the insult and insists the pride needs her.

Later, Vetr confronts Tamsyn privately. He warns her the Crags are dangerous and tells her to answer fire with fire if Nayden attacks again.

Then he forces her to face the pride’s reality: there are only twenty-nine dragons left, ten females including her, and merely five unbonded women. The pride expects those five to become breeders.

Tamsyn hears the word “duty” and feels old human trauma rising in her throat. When Vetr leaves, panic takes root.

She begins to think seriously about escape.

At dinner she senses how low she sits in the hierarchy and how much her presence depends on Fell’s memory. Fell was her mate, a dragon who lived among humans as Lord of the Borderlands.

He was taken and presumed killed a year ago. Tamsyn still wears his necklace and carries a bond mark on her palm that sometimes buzzes like a ghost.

Kerstin chats by her side, speaking bluntly about the attention Vetr receives from other women and the pressure they all face to bond. Tamsyn blurts that she might leave.

Kerstin warns that there is nowhere safer, and that the Crags are all they have.

The next morning Vetr calls a rekon south to gather information before winter. He chooses two warriors and, to everyone’s surprise, names Tamsyn as the third.

Nayden protests loudly, declaring her unready. Vetr dismisses him and asks Tamsyn directly if she can go.

She nods despite fear.

They fly by night to a hidden cottage in the Borderlands, shift to human, and ride toward the port city of Porthavn. Along the road Tamsyn sees the land in collapse: travelers starving, villages frightened, and pikes lined with impaled bodies.

A dying girl begs silently from one stake. Tamsyn wants to help, but Harald refuses.

Vetr ends the victims’ suffering with quick kills and tells Tamsyn their mission is not rescue but observation, meant to stop another Threshing—a human purge of dragons. He wants separation between their kinds and says her role is to bring back knowledge to build that barrier.

In Porthavn they meet Arran, who reports that Fell no longer rules the north. The lord regent has appointed his own son Stig as Lord of the Borderlands.

Stig survived past battles and is now infamous for cruelty, raising tithes and ordering executions and witch burnings. His soldiers are also pushing into the Crags, likely searching for Tamsyn.

As they speak, soldiers enter the inn and recognize her as Lady Dryhten, the former princess who married Fell, known to humans as the Beast. Vetr claims she is his sister, but the soldiers mock him and seize Tamsyn.

They drag her east toward Stig’s army while Vetr, contained fury in his eyes, does not strike.

On the ride Tamsyn considers killing her captors to protect the pride, yet she cannot bring herself to slaughter them, especially the youngest, Frode, who is terrified and barely trained. The men carry dragon-bone weapons and speak openly about Stig’s obsession with exposing dragons.

After three days they reach a massive camp of nearly a thousand. Tamsyn thinks she has failed everyone.

She is taken to Stig’s command tent, but he is away hunting. Guards sneer that Stig already has a wife.

Then a richly dressed young woman bursts out, crying Tamsyn’s name. It is her sister Alise—alive, grown, and married to Stig.

Back in the Crags, time grinds through a bitter winter. Tamsyn’s nightmares worsen.

One night she wakes screaming and, in the darkness, a man rushes into her den. Half-asleep and desperate, she mistakes him for Fell, clings to him, and kisses him.

As they tumble together, reality cuts through: his scent is wrong, her bondmark is silent, and the nickname he uses is not Fell’s. She shoves him away and strikes him.

The man is Vetr. He admits he has watched over her and suggests again that she should become his mate so she will never sleep alone.

Tamsyn rejects him and begs to know if Fell might still live. Vetr says no.

As winter traps them inside, training turns brutal. Tamsyn numbs herself with chores and wine, but her palm keeps buzzing.

She sees Vetr holding a baby with gentle ease and feels confusing warmth. Kerstin teases her about Vetr and asks if she would ever choose him.

Tamsyn insists she has no choice in mates and refuses to look at her own feelings.

Driven by unrest, she goes to Vetr’s den to talk. He is gone.

She opens a chest, pulled by a strange whisper, and finds Fell’s black opal necklace at the bottom. Vetr returns and catches her holding it.

She demands the truth. Vetr admits he retrieved the necklace the day skelm dragons took Fell and confesses he now believes Fell is alive.

Her bondmark flared in his presence, proof that the bond still exists. He hid this because the likely fate is earthing—captives buried alive for centuries.

The thought shatters Tamsyn. She refuses to accept helplessness.

She vows she will not take another mate while Fell lives and runs with the necklace.

That night she slips out into a snow squall to follow the pull of her bondmark. Kerstin catches her and insists on coming.

They trek on foot through blinding cold, hiding from searchers overhead. When the storm breaks, the buzzing in Tamsyn’s palm suddenly dies.

She spins in terror, unable to find its direction. Kerstin says that if it has gone cold, Fell is likely in a deeper svefn-like state from long burial—alive but unreachable.

Without guidance, Tamsyn collapses in despair.

Not long after, she and Fell find each other in the wild. Their reunion begins with violence; both shift and fight on instinct until recognition snaps into place and her bondmark blazes.

Relief floods them. They hide in a hot-spring cave, and Tamsyn tells him everything: Stig’s takeover, Alise as his wife, the camp hunting her, and the pride’s pressure.

Fell sees scars on her back and learns Stig once tortured her to force confession. Rage hardens his resolve to reclaim his lands and kill Stig.

Tamsyn admits Vetr tried to push her toward a new bond, including unwanted advances. Fell burns with jealousy and betrayal, but he does not blame her.

They decide to return to the Borderlands together.

They fly partway, then travel on foot to avoid lookouts. Three Borderlands warriors confront them, then recognize Fell alive and kneel in shock.

They escort him toward the Borg. Harpies attack, and because they cannot reveal dragon forms in front of humans, they fight with swords.

Two men die. Fell orders Tamsyn to run while he and Magnus cover her.

Tamsyn is ambushed by Stig and his soldiers. Stig knocks her out, demands she transform, and locks her in a dragon-bone cage built to hold her.

As the wagon rolls, Fell steps from the trees and commands her release. Stig calls him traitor and swings a dragon-bone sword at Tamsyn’s face to “prove” her nature.

Fell blocks the blow and bleeds purple, exposing himself. He shifts into his silver dragon, seizes Stig, and tears off his head in the sky.

Tamsyn shifts into her red-gold dragon and fights beside him. They rout the soldiers, leaving survivors alive, including a stunned Magnus.

Vetr and the pride arrive. He mocks their lack of secrecy and hints at killing witnesses.

Tamsyn stands between the brothers and refuses more slaughter. Vetr agrees to another path: he releases enchanted fog that drops the humans into deep sleep and wipes their memories.

He tells Fell to claim raiders killed Stig, then departs.

When the soldiers awaken, they accept the false story. Fell and Tamsyn ride to the Borg, now without its old protective mist.

They walk through the gates together to reclaim their home.

A year later, Fell and Tamsyn rule the Borderlands, quietly rebuilding and secretly flying at night. Vetr rules the Crags, still watching from afar.

In the City, the lord regent mourns Stig and plots revenge, the Veturland king plans war, and a witch works a new spell in the dark—signaling that peace will not last.

Characters

Ashild

Ashild is introduced as a remnant of a shattered world, a dragon mother surviving in scarcity seventy-seven years after the Hormung. Her characterization rests on a tension between fierce instinct and exhausting grief.

She is powerful by nature, yet the story meets her in a state of starvation and isolation, which makes her vulnerability as important as her strength. Her love is singularly focused on her twin sons, and everything she does—hunting in daylight, worrying over dwindling stores, weighing whether to rejoin a pride—flows from that maternal drive.

The trauma of losing Sigurd shapes her internal world; the severed bond leaves her unable to imagine taking another mate even when survival demands it. She also carries a quiet defiance against dragon tradition: her fear that the pride would reject her human-looking child reveals both her protectiveness and her awareness that old rules may no longer fit the future.

Ashild’s final stand is tragic but not passive. She fights savagely, buying her sons time, and in death her last act is a form of will—locking eyes with both boys, pushing them toward survival.

Her arc is brief but foundational, establishing the cost of extinction and the fierce, lonely courage that echoes through the rest of the book.

Sigurd

Sigurd exists mostly through Ashild’s memory, but that absence is part of his role. He is the lost mate whose disappearance cut the bond and broke Ashild’s hope in pride or partnership.

The black opal he gave her becomes a symbol of that severed connection, later stolen by humans in a moment that compounds the violation of her death. Sigurd is thus less a present character than a shaping force: his loss explains Ashild’s refusal to remate and her dread of pride expectations, and he sets a thematic precedent for the book’s exploration of bonds—how they sustain, how they haunt, and how the uncertainty of a mate’s fate can freeze a life in grief.

Ashild’s twin sons (including Vetr as a child)

The twins begin as silent witnesses, but they embody the future Ashild dies for. Their dual nature—dragon truth inside human appearance—represents the evolving identity of dragonkind.

One twin is explicitly named Vetr, and his survival positions him as a living bridge between old dragon lineage and a changed world. The boys’ helplessness during Ashild’s slaughter intensifies the tragedy, yet their continued existence also plants the story’s core question: what kind of dragons will remain when tradition, biology, and necessity collide?

Even in childhood, their presence forces others to confront difference, and the fear Ashild feels for their acceptance foreshadows the ideological conflicts later within the pride.

Tamsyn

Tamsyn is the emotional center of A Scar in the Bone. She is shaped by dislocation: raised human, only recently revealed as dragon, and therefore treated as an outsider in both worlds.

Her defining trait is resilience under layered grief and pressure. She trains relentlessly despite humiliation, refuses to collapse under Nayden and Kerstin’s bullying, and survives burns and ridicule without surrendering her sense of self.

Yet her toughness doesn’t erase softness; she is horrified by human cruelty on the road, struggles with the dragon doctrine of killing witnesses, and repeatedly chooses mercy even when it endangers her. Fell’s death—or presumed death—haunts her, and the alive-feeling bond mark becomes her psychological tether, keeping her suspended between hope and despair.

Vetr’s insistence on her reproductive “duty” triggers trauma rooted in her past as a political pawn among humans, revealing that her fears aren’t only about dragons but about losing autonomy again. Her eventual decision to flee the pride to search for Fell shows both her refusal to accept imposed narratives and her willingness to risk everything for love.

When reunited with Fell, Tamsyn becomes more than a survivor; she is a moral counterweight to the harsher instincts of dragons around her. Her insistence on sparing human witnesses and resisting needless slaughter signals her growth into leadership grounded not in dominance, but in conscience.

Vetr

Vetr is a complex alpha figure whose authority blends genuine responsibility with blunt survivalism. As leader of the Crags pride, he is defined by pragmatism sharpened into severity.

He intervenes to stop Nayden’s rule-breaking not only out of fairness but because discipline is existential for a hidden species. His mist-shader power and commanding presence make him both protector and enforcer, and the pride’s reliance on him gives his decisions enormous moral weight.

Vetr’s central contradiction is that he values Tamsyn as necessary to dragonkind’s continuation while also treating her like a strategic resource—a breeder in a dwindling population. That utilitarian view is not simple cruelty; it is fear of extinction dressed as duty, and he believes harsh truths keep the pride alive.

His lie about Fell’s fate is similarly double-edged. He hides the possibility of Fell’s survival out of a grim mercy, convinced the likely truth would destroy Tamsyn, yet the deception reveals his tendency to decide for others what they can bear.

His romantic pursuit of Tamsyn is complicated by grief for his twin and by longing that edges into opportunism; he offers safety and bond as both comfort and solution, but he cannot fully separate desire from political necessity. By the end, ruling the Crags and still longing for her, Vetr stands as a portrait of a leader trapped between love, guilt, and the brutal arithmetic of survival.

Fell

Fell is the embodiment of fierce loyalty and wounded sovereignty. As Tamsyn’s mate, his bond with her is portrayed as deep, instinctive, and enduring beyond apparent death.

His survival after being buried by skelm dragons reframes him as both victim and avenger. He returns not softened but sharpened: furious at betrayal, enraged by Stig’s usurpation, and hungry to reclaim his people and lands.

Yet his rage is not indiscriminate. When Tamsyn confesses Vetr’s advances, Fell’s pain is real, but he refuses to blame her, showing a capacity for empathy that balances his violence.

His relationship with power is personal rather than abstract; he fights because his home was stolen and because the people under his rule suffered. The discovery of scars on Tamsyn’s back crystallizes his protective nature into vengeance, making Stig’s punishment feel inevitable.

Fell is also a symbol of dragon-human intersection: once lord among humans, secretly dragon, he navigates identity as both obligation and weapon. His public shift and the purple blood reveal are decisive moments where secrecy yields to survival and justice.

By reclaiming the Borderlands with Tamsyn, Fell becomes a ruler marked by quiet resolve rather than spectacle, a man-dragon whose love and wrath are equally elemental.

Nayden

Nayden represents the pride’s internal hostility toward difference. He is aggressive, competitive, and insecure, using cruelty to protect his sense of superiority within a threatened hierarchy.

His bullying of Tamsyn arises partly from prejudice against her human upbringing and partly from fear that her presence disrupts established pecking orders. His rule-breaking fire-breath in the arena is telling: it is a tantrum of someone who believes strength entitles him to dominance, even at the cost of communal safety.

His accusation about her purple blood and bytte failure is less about truth than about shaming her into alienation. Nayden embodies the instinctual, survival-at-all-costs faction of dragon society, a figure whose hostility is dangerous not simply because he is violent, but because he would rather fracture the pride than accept change.

Kerstin

Kerstin is a lively, reckless earth dragon whose surface chatter masks a deeper function in the story: she is both mirror and catalyst for Tamsyn. Unlike Nayden, she engages Tamsyn socially, even when she’s tactless or self-interested, and her presence offers Tamsyn a thread of belonging in the pride’s isolating hierarchy.

Kerstin’s bluntness at dinner, calling out Estrid and Gudru, shows her disregard for rank and her youthful impulse to puncture tension with noise. Yet her most important moment comes when she insists on joining Tamsyn’s escape.

This is not mere adventure-seeking; it is loyalty rooted in empathy, and possibly her own fear of being forced into unwanted mating. She knows earthing is real and chooses solidarity over safety, becoming the companion who makes Tamsyn’s desperate quest possible.

Kerstin thus embodies a new kind of dragon: less bound to rigid tradition, more willing to accept emotional truth, even if she doesn’t always understand the cost.

Harald

Harald functions as the pride’s practical warrior and a representative of dragon caution toward humans. On the rekon, he is steady, experienced, and skeptical of intervention.

His refusal to save the impaled victims is cruel on the surface but consistent with the mission’s logic and the pride’s survival code. Harald’s value in characterization lies in showing how trauma and secrecy create hardened ethics.

He isn’t sadistic; he is disciplined to prioritize the species over individual strangers. His presence also highlights the contrast between Tamsyn’s lingering human compassion and the pride’s cultivated detachment.

Arran

Arran is the recon’s informant figure, bringing political clarity and grounding the dragon mission in human reality. His role emphasizes his competence and awareness of shifting power in the Borderlands.

Through him, we see how Fell’s absence destabilized the north and allowed Stig’s reign to flourish. Arran’s loyalty appears aligned with Fell’s former rule, and he serves as a bridge between dragon interests and human political structures, demonstrating that not all humans are enemies and that alliances, however fragile, still matter.

Aksel

Aksel is a senior pride voice who reinforces the martial, ordered life inside the Crags. His command to gather in the arena signals his role as organizer and keeper of routine.

While not deeply individuated in the summary, he represents the pride’s institutional side—the machinery that keeps a dwindling people trained, obedient, and ready. His function helps illustrate that Vetr’s leadership is supported by a broader structure of elders and warriors, not merely personal dominance.

Anders

Anders appears as discipline embodied. When Nayden protests against Tamsyn’s selection for the rekon, Anders moves to reprimand him, marking himself as an upholder of hierarchy and loyalty to Vetr’s authority.

He stands for internal order, a reminder that dissent in a small, endangered society is not tolerated lightly. Anders’ presence reinforces the pride’s tension between individual ego and collective survival.

Brenna

Brenna is a steadying maternal and authoritative force within the pride, visible both in her stern control of dinner disruptions and in the tenderness with which Vetr holds her child. As skeppar, she occupies a role tied to order and tradition, but her motherhood also humanizes the pride’s harshness, reminding the reader what the survival project is for.

Through Brenna, the pride’s focus on breeding becomes emotionally grounded rather than purely strategic.

Mirja

Mirja, Brenna’s baby, symbolizes fragile continuity. Her existence makes the pride’s urgency about survival concrete, while also unsettling Tamsyn—she feels warmth toward the child but unease at what motherhood might be forced to mean for her.

Mirja functions as an emotional lens through which the stakes of extinction and duty become intimate.

Estrid and Gudru

Estrid and Gudru are less individualized in the summary, but together they represent rivalry and scarcity among the remaining unbonded females. Their quiet competition for Vetr’s attention underscores how limited choices distort relationships in the pride.

They are products of a world where mating is political and urgent. Their tension at dinner, sparked by Kerstin’s taunting, reveals a social environment where desire, status, and survival are braided tightly together.

Erling

Erling is named among the unbonded females, indicating her symbolic role in the pride’s dwindling reproductive future. Even without detailed scenes, her inclusion reinforces the demographic pressure that drives Vetr’s arguments.

She represents the silent weight of expectation placed on dragon women, a presence that forms part of the emotional cage Tamsyn fears.

Stig

Stig is the primary human antagonist, a study in cruelty empowered by fear and obsession. Once presumed dead, his survival and rise to lordship transform him into a living nightmare for both humans and dragons.

His rule is defined by spectacle of terror—impalements, higher tithes, witch burnings—not simply for punishment but to consolidate power through horror. Stig’s obsession with exposing Tamsyn as dragon reveals a paranoid hunger for dominance: dragons are both his political threat and his personal fixation.

His treatment of Tamsyn, including torture and imprisonment in a dragon-bone cage, shows his belief that identity can be beaten out of someone, and that monstrosity is whatever he labels as such. Yet Stig is not only brutal; he is ambitious and strategic, marrying Alise to legitimize power and raising an army to penetrate the Crags.

His death at Fell’s hands is thematically fitting, because his own dragon-hunting tools become irrelevant once dragons refuse to stay hidden.

Alise

Alise is Tamsyn’s sister, and her reappearance as Stig’s wife is a shocking convergence of past and present. She embodies the human political web that Tamsyn fled: alliances made through marriage, survival through proximity to power, and identity shaped by circumstances beyond one’s choosing.

The summary doesn’t show her full stance—whether she is complicit, trapped, or strategically adapting—but her emotional rush toward Tamsyn suggests lingering sisterly attachment despite her new role. Alise represents the painful truth that family can be reshaped by politics, and that human lives, like dragon ones, are often bent under regimes of duty.

Frode

Frode is the youngest soldier escorting Tamsyn, and his presence is crucial to her moral conflict. He is frightened, likely conscripted, and not yet hardened into cruelty.

Through Frode, the narrative complicates the dragon doctrine of killing witnesses. Tamsyn’s inability to kill him shows her enduring empathy and her refusal to become a simple predator of humans.

Frode functions as proof that innocence still exists in the human world, even inside an oppressive army.

Jorgen and Ari

Jorgen and Ari are soldiers within Stig’s force, and they serve as embodiments of the regime’s machinery. Jorgen’s role in delivering Tamsyn to camp shows the casual brutality and entitlement Stig’s army carries, while Ari’s constant suspicion and readiness with his sword demonstrates how fear of dragons warps human behavior into paranoia.

Individually they are not deeply explored, but together they represent the fearful, violent infrastructure that allows Stig’s tyranny to operate.

Magnus

Magnus is a Borderlands warrior who confronts Fell and Tamsyn, then kneels in shock when he recognizes Fell alive. He represents the human side of loyalty to Fell’s former rule—men who once served a lord they believed dead.

Magnus’ terror after witnessing dragons shift is honest and human, and his survival becomes a test of Tamsyn’s insistence against needless slaughter. He is thus a hinge character between worlds: a human witness who could become a threat, but is spared and memory-wiped, allowing the fragile coexistence Fell and Tamsyn envision to continue.

Themes

Survival, Hunger, and the Brutality of Scarcity

The opening situation in A Scar in the bone is survival reduced to its rawest form: a mother leaving safety in daylight because hunger is stronger than fear. Ashild’s starvation isn’t just physical decline; it reshapes her choices, compresses her world, and forces her to weigh futures she would otherwise reject.

The landscape has been hunted empty, the tunnels that once meant refuge now feel like a narrowing trap, and the jewels of her hoard offer power without nourishment. This contrast makes scarcity feel cruelly ironic: wealth that cannot feed a child is revealed as hollow.

Her decision point about joining a pride is also framed by deprivation. She doesn’t consider community out of desire, but because scarcity corners her into it.

That pressure exposes how survival can demand betrayal of personal grief, bodily autonomy, or cultural identity. When the humans arrive, the violence is not portrayed as heroic conflict; it is the predictable outcome of desperation meeting greed.

Ashild’s body is too weak to win, which emphasizes that scarcity doesn’t just kill through slow starvation, it also strips away the strength needed to resist other threats. Her death is horrifying, but the emotional core sits in her final calculation: if humans believe her sons are human, the mistake might save them.

Survival becomes a moral ledger where she spends her last moments buying their future with her own life. Later sections echo the same logic in a different register.

Tamsyn’s world inside the pride is also defined by resource anxiety, just shifted from food to safety, belonging, and strategic advantage. The pride’s obsession with secrecy, strict training, and reconnaissance missions comes from the same post-catastrophe survival mindset that drove Ashild into the sky.

Even Vetr’s cold insistence on self-preservation is rooted in collective scarcity of numbers, territory, and time. The human world beyond the Crags mirrors this with impalements, poverty, and a regime that weaponizes fear during hard times.

Scarcity thus fuses the two societies into a shared brutality: when resources shrink, compassion is treated as a liability, and life is measured by what can be protected, eaten, or controlled. The book keeps returning to the idea that extinction is not a distant threat but a daily condition, and that in such a condition, every relationship and institution is bent by the logic of survival.

Identity, Belonging, and the Pain of Being Between Worlds

Tamsyn’s struggle is not only about discovering she is dragon; it is about living in the unstable space between forms, cultures, and expectations. Raised among humans, she enters the pride with habits, language, and instincts shaped by a different moral order.

The pride sees her as useful yet suspect, a contradiction that becomes central to how she sees herself. Her purple blood under stress is a visible marker of that liminality: she cannot fully perform the discipline that makes dragons appear human, and so her body exposes her insecurity whenever she is pushed.

The sparring scene dramatizes this psychologically. She fights in human form under rules meant to preserve secrecy, yet her opponents slip in and out of dragonhood, using strength and cruelty to assert dominance.

Tamsyn survives through tactics learned in a human world where size isn’t everything, which makes her both threatening and alien to them. Her placement at dinner, questions dismissed, and social isolation show belonging as something policed through ritual hierarchy.

Even when Vetr declares she is “one of them,” the declaration feels like a strategic claim rather than unconditional acceptance, leaving her identity tethered to what she provides rather than who she is.

Her bond with Fell complicates this further. The bond mark and necklace are not just romance tokens; they are anchors to a self she fears losing.

Grief fractures identity into before and after: before, she was a human princess turned dragon mate; after, she is a widowed shifter treated like a breeding asset. Vetr’s resemblance to Fell, plus his role as alpha, creates a constant mirroring effect that disturbs her sense of who she is allowed to be.

The mistaken intimacy scene shocks because it reveals how grief can blur identity boundaries, making desire and memory collide in humiliating ways. Her flight from the pride is also an identity act: she chooses the truth of her bond over the pride’s definition of her duty.

When the bond goes silent in the wilderness, the collapse she experiences is not only fear for Fell; it is fear that the self built around that bond might evaporate.

The reunion with Fell restores the mark and seems to restore her wholeness, yet the novel does not present this as a simple return. The scars on her back, the trauma of torture, and her year of enforced dragon discipline mean she now carries both worlds inside her permanently.

In the final state of ruling quietly while flying secretly at night, identity remains split but no longer purely painful. She inhabits both roles with intention, refusing to erase either.

The story suggests that belonging is not a location or a single people; it is a negotiated state created by choice, loyalty, and the ongoing work of living with contradiction.

Love, Grief, and the Persistence of Bonds

Loss is treated in A Scar in the bone as a force that rearranges time. Ashild’s grief for Sigurd is still open two years after his disappearance, shaping her resistance to taking a new mate even when survival demands it.

Her love is not romantic nostalgia; it is a living commitment that makes the future feel like betrayal. That same emotional structure carries into Tamsyn’s arc.

Her bond with Fell lingers as a physical sensation, a pulse in the palm that refuses to accept the official story of his death. The bond mark becomes a kind of second heartbeat, turning grief into a bodily condition rather than a passing mood.

When she notices her birthday unseen, the grief is not for the date itself but for the life that used to witness her. The wind that seems to answer her whisper of Fell’s name highlights how love, in this narrative, is tied to magic and environment, as if the world itself remembers.

The nightmare and mistaken encounter with Vetr show grief at its most destabilizing. Desire here is not a betrayal of love but an overflow of loneliness, a human need that erupts in the absence of certainty.

The moment she realizes the man is not Fell is brutal partly because it exposes how deeply grief can hollow out perception. Yet the scene also reveals how love persists even in confusion: her body reaches for Fell because the bond has trained her to need him.

Vetr’s later confession that the bond indicates Fell might be alive reframes grief as incomplete knowledge. Tamsyn’s fury at being lied to is the fury of someone whose mourning was manipulated.

It is not only the possibility of rescue that drives her; it is the demand that love be honored with truth.

When Tamsyn and Fell reunite, the bond does more than reconnect lovers; it restores a sense of moral order. The flare in her palm confirms that what she trusted in her body was real, validating her refusal to move on under pressure.

Their physical reunion is intense because it carries a year of suspended life, but the emotional reunion is equally severe: they must integrate the damage done while apart. Fell’s reaction to her scars and to Vetr’s advances shows love turning into protective rage, but also into careful understanding.

He is wounded by the knowledge of Vetr’s closeness, yet he does not punish Tamsyn for surviving emotionally in the void he left behind. That distinction matters: love here is not possessive purity but the ability to see the other’s suffering clearly.

Even in the ending, bonds continue to echo outward. Vetr’s longing for Tamsyn is not a romantic subplot tacked on; it shows love as a political and communal complication.

The pride’s survival depends on bonds, and yet bonds create rivalries, grief, and the risk of repeating old harms. The book treats love as something that can heal, mislead, and motivate war, but above all as something that does not vanish simply because the world declares it finished.

Power, Control, and the Cost of Fear

Authority in A Scar in the bone is built on fear and maintained through spectacle. The humans who kill Ashild do so not only to remove a threat but to claim dominance and treasure, and their use of a dragon-bone axe makes that dominance literal: power is forged from the bodies of the conquered.

The scene is staged like a hunt, and the leader’s savoring of victory turns violence into ritual. This early example sets up a political world where control is reinforced by symbolic cruelty.

Later, the human regime under Stig magnifies that logic. Impalements, increased tithes, and witch burnings are not random brutality; they are governance by terror.

The pikes with living victims are especially telling. Keeping people alive in agony extends punishment into public warning, making bodies into boundary markers for acceptable behavior.

Fear thus becomes infrastructure.

Dragons replicate some of this structure in subtler ways. The pride’s hierarchy at the table, the enforcement of training rules, and the readiness to punish Nayden reveal a society that relies on strict order under threat of extinction.

Vetr’s authority is practical and protective, but it is also coercive. His blunt calculation of female numbers and talk of breeding reduces individuals to resources.

He believes he is speaking in survival terms, yet the effect on Tamsyn is domination through inevitability. Duty becomes a weapon because it is framed as non-negotiable.

The fact that Tamsyn’s panic is triggered by that word shows how power is inseparable from her past captivity; fear travels with her across societies.

The mission south makes the tension between observation and intervention a moral test of power. Vetr insists on distance, describing humans as outside their concern, while still killing suffering victims to end their pain.

His deflection when questioned suggests that power often hides behind strategic language. He wants a wall between species, but walls are also tools of control, deciding who is protected and who is abandoned.

When soldiers seize Tamsyn in the inn, Vetr’s refusal to fight shows another facet of power: restraint can be moral, but it can also be complicity when it protects strategy over a person. Tamsyn’s internal debate about killing witnesses exposes her own struggle with the dragon code of control.

She cannot commit the act because her human upbringing resists the dragon logic of erasing threats. Her mercy is risky, and the book does not romanticize it; it presents mercy as a choice that carries consequences in a fearful world.

The climax where Stig forces a “proof” of dragon nature frames control as obsession. He needs to expose and dominate what he fears, and his dragon-bone cage is a technological extension of that need.

Fell’s revelation through purple blood flips the power dynamic instantly, showing how hidden identities destabilize oppressive systems. Yet even after Stig’s death, fear does not disappear; it migrates to new rulers plotting revenge.

The dragons’ memory-fog solution is a final illustration of power’s ambiguity. It prevents massacre and protects secrecy, but it also violates human agency by rewriting minds.

The cost of fear, then, is not only suffering under tyrants; it is the erosion of ethical clarity for everyone trying to survive.