Anne of Avenue A Summary, Characters and Themes

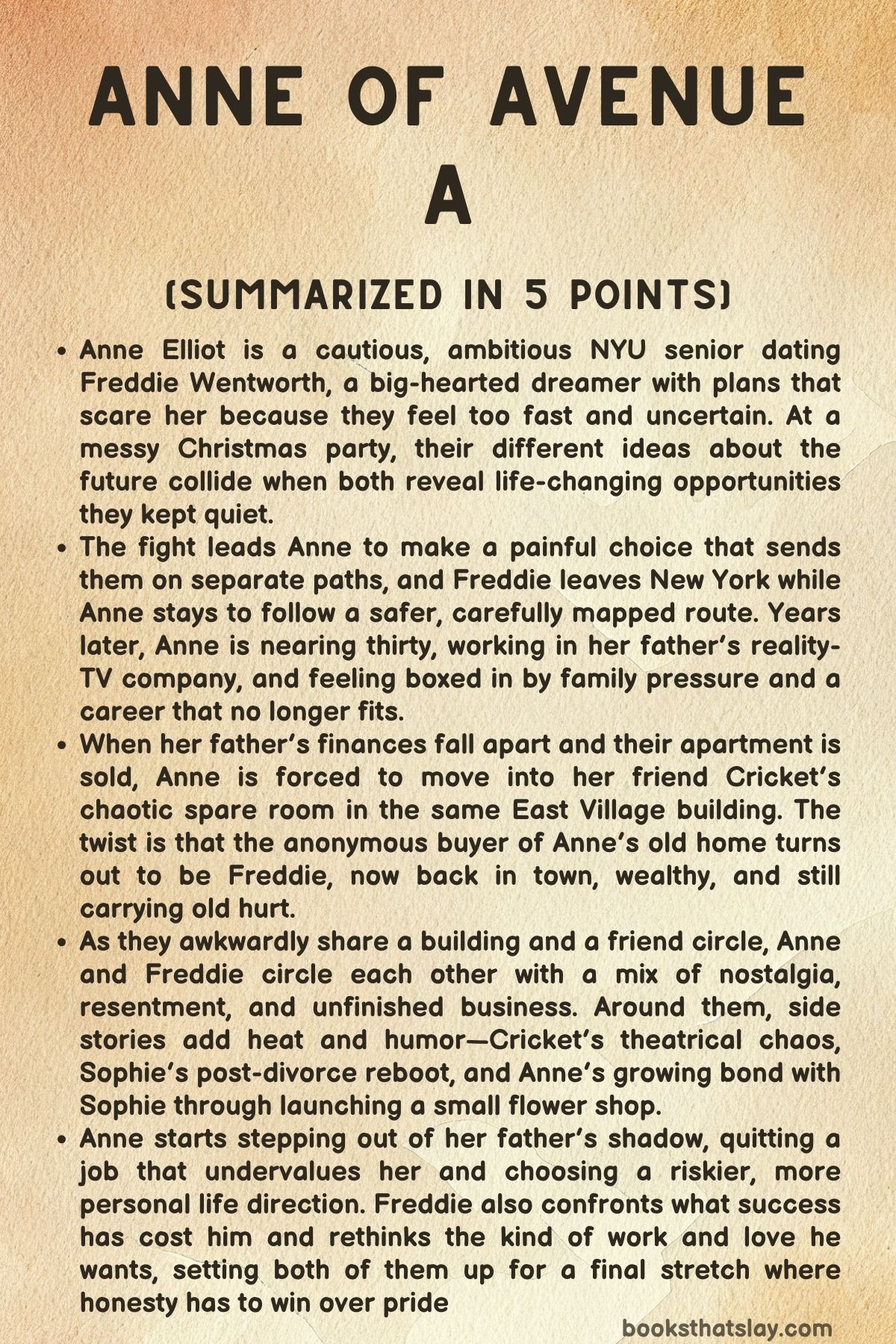

Anne of Avenue A by Audrey Bellezza and Emily Harding is a contemporary New York romance inspired by Persuasion, following two former college loves who collide again as adults. Anne Elliot once chose practicality over passion, ending her relationship with Freddie Wentworth right before graduation so he could chase a dream abroad.

Eight years later, her careful life is wobbling—her family’s TV business is failing, her housing is unstable, and she’s tired of being the responsible fixer. When Freddie returns wealthy, restless, and unexpectedly buys her childhood apartment, their unfinished story reopens. The novel tracks second chances, ambition, family pressure, and the hard work of choosing your own life.

Summary

Anne Elliot is finishing her senior year at NYU when she goes to her boyfriend Freddie Wentworth’s boisterous Christmas party at a neighborhood bar. She feels a little out of place in her simple outfit amid the holiday chaos, but Freddie’s goofy Santa costume and their easy affection make her feel safe.

After a drink is spilled on her, he takes her outside into the snow, wraps her in his coat, and they share a quiet moment that shows how deeply they know each other. Freddie gives her a small gift—a silver bracelet with a compass charm meant to collect memories from places they’ll travel together.

Then he shows her life-changing news: he’s been accepted into NYU’s Buenos Aires program with funding for his hydroponics project, and he wants to leave after graduation. He assumes Anne will come for at least part of the year, because they’ve talked for months about exploring the world side by side.

Anne’s first reaction is not joy but worry. She starts listing costs, logistics, and risks.

Freddie, thrilled and nervous, wants celebration, not a spreadsheet. The tension forces Anne to admit what she’s been hiding: months earlier she applied to Columbia Business School and was accepted into an MBA program starting in August.

Freddie is stunned that she kept this secret while criticizing his surprise plan. Their argument exposes a deeper split.

Freddie wants to follow opportunity and purpose wherever it takes him; Anne wants a carefully built future with stable steps and clear plans. The fight turns raw, with Freddie accusing her of letting her mother’s expectations steer her life, and Anne realizing Freddie might give up Argentina just to stay with her.

She can’t bear the thought of him shrinking himself for her, so she decides to end things, even though she doesn’t say the words that night. After reading one of his tender folded notes at home, she quietly commits to breaking up after Christmas.

Freddie leaves for Buenos Aires soon after, and their connection is severed.

Eight years pass. Anne is nearly thirty and still in New York, working for her father Walter Elliot at his small production company, Kellynch Productions.

She manages edits and finances for their only profitable reality show, Divorce Divas. When a violent on-camera fight between two stars becomes a legal case, all footage is seized as evidence and production halts indefinitely.

With no new episodes, the company loses its income stream, and layoffs loom. Anne is already exhausted when she learns another blow is coming from home: Walter’s latest divorce has gutted his finances.

His much younger ex-wife wins half their shared assets, including half ownership of the family apartment in the Uppercross co-op. Walter has secretly mortgaged the place and can’t buy her out.

The apartment must be sold, and Anne will have to leave the home she grew up in.

At the same time, Freddie returns to New York. He built his hydroponics startup into a global success, then sold it and is newly wealthy but hollowed out by years of travel and corporate pressure.

He wants a base in his hometown and begins apartment hunting with a realtor and his sister Sophie. He falls for a bright two-bedroom in the Uppercross building and buys it in cash, not knowing it’s Anne’s childhood home.

The sale stays anonymous, so Anne doesn’t learn the buyer’s identity. During a wine night with neighbors James, Cricket, and Bev, she vents about losing the apartment and scrambling to find housing.

Cricket offers her a temporary room in her own rent-controlled unit, ignoring the legal gray area. Anne accepts out of necessity and moves into Cricket’s chaotic, patchouli-scented apartment filled with theater flyers, K-pop posters, and mismatched furniture.

She tries to treat it like a short stopover while she figures out work and a new place to live.

The collision comes fast. A knock on the door reveals Freddie in a suit, newly moved in upstairs.

Both freeze. Cricket breezes in, introduces them as roommates and new owner, and casually drops that Freddie bought Anne’s father’s apartment.

Anne is mortified; Freddie is shaken. He retreats to his empty new home, walking through rooms still echoing with Anne’s past, realizing he’s about to repaint and erase the space she once inhabited.

Old hurt rises, especially at hearing Anne describe him as just someone she knew at NYU.

They avoid each other for days, but the building makes distance hard. Freddie’s housewarming party draws a crowd, and Sophie drags Anne upstairs before she can escape.

Sophie loudly announces their history to the room, which needles Freddie and embarrasses Anne. Freddie tosses a sharp comment about her business-school dreams, and Anne leaves early, furious and rattled.

Still, Sophie and Anne reconnect the next morning over coffee. Sophie has recently divorced and is trying to revive her flower shop.

Anne, who has years of financial and operational experience from Kellynch, offers to help her build a real plan. The two women begin working together, with Anne setting budgets, systems, and marketing ideas.

Sophie’s gratitude gives Anne a sense of usefulness separate from her father’s mess.

Freddie, meanwhile, is courted by a polished green-energy startup called AirSoil. Their CEO pitches him a high-profile executive role that would turn his farming technology into a luxury brand.

Freddie feels the pressure to say yes, but he’s uneasy about selling out the values that built his company. His friends remind him that after the sale he has time to decide who he wants to be next.

Life in the Uppercross keeps nudging Anne and Freddie together. During a small crisis involving a beat-up Christmas tree, Freddie helps her carry it upstairs and they decorate it in a quiet, almost domestic bubble.

The warmth cracks their defenses. Freddie admits he can’t do strangers with her and asks if they can try being friends.

Anne agrees, hoping they might rebuild something safer first. Their tentative truce leads to longer conversations, shared jokes, and a soft return of familiarity.

Thanksgiving brings a turning point. Anne’s father invites her to dinner, but she walks into a flashy gathering designed to celebrate a secret licensing deal for Divorce Divas, while the crew remains jobless and Anne’s work is treated like a convenience.

For the first time, she refuses to absorb his chaos. She quits on the spot and walks out, feeling the shock of freedom.

Soon after, at a rooftop birthday gathering in the building, she and Freddie fall into the same orbit of friends, laughter, and late-night calm. Freddie escorts her downstairs when she’s tipsy.

In her tiny room, emotions spill out: she admits she never stopped caring, and he sees a hidden box of his old notes, proof that their past has been alive in both of them. The dam breaks.

They kiss, then sleep together with the intensity of eight years of silence collapsing at once.

Morning doesn’t stay tender. Over coffee, old fractures reopen.

Freddie bristles at the idea of Anne returning to TV work, and Anne pushes back at his renewed criticisms of her mother’s influence. The argument spirals into their breakup history: Freddie says she ended things before they even tried; Anne says he left without making space for her dreams and punished her by blocking her.

Hurt turns sharp, and Freddie walks out coldly, leaving Anne stunned and angry at herself for hoping physical closeness meant emotional clarity.

Instead of sinking back into caution, Anne starts choosing honesty. Bev tells her there isn’t one perfect path, only the one you commit to.

When Theo, a former coworker, offers her a low-level job on a new show after leaning on her expertise, Anne sees the pattern of being used. She refuses the offer and decides to go all-in with Sophie on the flower shop.

She helps Sophie choose a name—Eufloria—and signs on as a fifty-fifty partner, stepping into a life she wants rather than a life that looks safe on paper.

Freddie has his own reckoning. At AirSoil, the CEO lays out a plan to make hydroponics a celebrity-endorsed status product.

Freddie rejects it outright, insisting his work should serve communities, not vanity. Walking away reignites the nonprofit vision he once had in college.

Time with his parents in Queens reminds him of why he started. He admits he still loves Anne.

His father tells him to apologize and decide which differences he can live with.

Eufloria’s launch party arrives in fresh snow. The shop is crowded, stylish, and alive.

Anne is proud and nervous, scanning the door for Freddie and feeling a bruised disappointment when he doesn’t appear inside. Her mother Bianca shows up briefly, and instead of criticizing Anne’s change of course, she surprises her by saying she’s proud and never wanted her trapped in finance.

Outside, Freddie arrives late and runs into Bianca. She finally tells him the truth Anne never said years ago: Anne broke up with him so he would go to Buenos Aires without sacrificing his future for her.

The revelation reframes everything. Freddie realizes her practicality was also love, and he understands the cost she paid.

He doesn’t want to steal the spotlight from Anne’s night, so he waits outside and writes her a folded paper-triangle letter like the ones he used to give her. He asks Sophie to deliver it after the party ends.

When Anne reads the note, she finds the words she has wanted for years: Freddie loves her, is sorry, and will be waiting at home if she wants him too. Anne runs through the snow to his apartment, not stopping for a coat.

Freddie wraps her in a blanket and apologizes for his bitterness, promising they can face hard conversations together instead of running from them. Anne answers with the truth she’s been circling for eight years: she loves him.

They reconcile fully, choosing each other with open eyes.

A year later, at a New Year’s Eve karaoke party with their close friends, Eufloria is thriving and expanding, and Anne feels anchored in a life she chose. Freddie takes her outside, gives her the very first paper triangle he wrote the night they met and kept all these years, then asks her to marry him.

Anne says yes, and their second chance becomes a shared future built on both love and intention.

Characters

Anne Elliot

Anne Elliot is the emotional and moral center of Anne of Avenue A, a woman whose defining trait is her sense of responsibility—sometimes to the point of self-erasure. In college, she is already a careful planner, measuring life in budgets, logistics, and sensible timelines, which makes her feel older than her peers and quietly out of step with Freddie’s spontaneity.

Her decision to break up with Freddie is not rooted in a lack of love but in a sacrificial instinct: she believes she must protect his future even if it costs her own happiness. Eight years later, we see the long shadow of that choice.

She has built a life that looks “successful” on paper—MBA, steady career at her father’s company, competence under pressure—but internally she is exhausted, emotionally undernourished, and stuck in patterns of pleasing difficult people. The slow reawakening she experiences in the Uppercross building is less about rekindling romance and more about reclaiming agency.

By choosing Eufloria and refusing both Theo’s undervaluing offer and her father’s manipulative orbit, Anne finally learns that a meaningful life does not require perfect certainty, only honest desire and the courage to live with the messiness of real commitment.

Freddie Wentworth

Freddie Wentworth embodies the tension between idealism and disillusionment in Anne of Avenue A. As a student, he is big-hearted, adventurous, and tender in ways Anne privately treasures—his handwritten notes, his compass bracelet, his dream of shared travel. His anger at the breakup is not petty; it comes from feeling blindsided and reduced to a footnote in Anne’s “sensible plan.” The eight-year gap transforms him outwardly into a polished success—wealthy, composed, moving through New York in expensive suits—yet inside he remains the same fiercely principled person.

He is tired of corporate machinery, allergic to compromise that betrays his values, and quietly lonely despite his achievements. Freddie’s emotional journey is about learning to reopen a wound he sealed with distance.

His initial stiffness around Anne masks fear that loving her again will mean reliving rejection, but the story reveals that his love never truly left—symbolized by the napkin note and his lifelong habit of folding letters for her. When he rejects Mark Segel’s luxury-brand vision and returns to his nonprofit dream, he reclaims the core self Anne once loved.

His eventual apology and love letter show his growth: he no longer wants a romance built on sacrifice or misunderstanding, but one built on choosing each other honestly and repeatedly.

Sophie Wentworth

Sophie is a vibrant catalyst who pushes both Anne and Freddie toward change. She enters the story as Freddie’s fiercely affectionate sister—pink-haired, bold, socially fearless—and she refuses to let old wounds remain politely buried.

Her own divorce from Jimmy adds depth to her role: she understands heartbreak not as abstract sympathy but as lived reality, and this gives her a quiet wisdom beneath her sparkling exterior. Sophie’s flower shop dream is as much about rebuilding her identity after a failed marriage as it is about starting a business.

Through her partnership with Anne, she offers Anne a different model of adulthood—one that values joy, risk, and creativity alongside competence. Sophie also functions as an emotional truth-teller, repeatedly pressing for the real story between Anne and Freddie and nudging them away from avoidance.

Her steady belief in Anne’s brilliance and her warmth toward Freddie help bridge the gap between them, making her both a sister and a kind of matchmaker who never treats love like a passive accident but like something worth fighting for.

Walter Elliot

Walter Elliot represents the glamorous, selfish instability that has shaped Anne’s over-responsibility. As Anne’s father and the head of Kellynch Productions, he is charming in public but careless in private, living beyond his means and depending on Anne to clean up his messes.

His divorce from MacKenzie and the forced sale of the Uppercross apartment expose how hollow his façade is: he has mortgaged their home, saved nothing, and treats crises as inconveniences others must fix. Walter’s manipulations—secret licensing deals, surprise Thanksgiving ambushes, constant demands for updates—illustrate why Anne learned to equate love with labor.

He is not openly cruel so much as perpetually self-centered, unable to see Anne as a daughter with needs rather than a competent extension of his brand. Anne’s decision to quit working for him is a major liberation, because it is the first time she refuses to be the adult in their relationship.

Walter thus serves as the primary force Anne must outgrow to become fully herself.

Bianca Elliot

Bianca is a complicated mix of distance, control, and surprising tenderness. Living largely abroad and calling from places like Paris, she exerts influence through expectation rather than presence, and Anne has internalized her voice as a standard of “the right choice.” Bianca’s past embarrassment over Freddie—when Anne called him her “friend”—highlights how much Anne learned to hide vulnerability in order to appear composed.

Yet Bianca is not a flat antagonist. Her late-story confession that she never wanted Anne trapped in finance reframes her as someone who may have pressured Anne out of fear rather than disdain.

When she expresses pride in Anne’s choice of Eufloria, it acts like a kind of emotional permission slip Anne didn’t know she needed. Bianca’s arc suggests that parental influence can be both wounding and redeemable, and that growth sometimes requires seeing the humanity behind the pressure.

Theo Travers

Theo Travers is a mirror for the professional version of Anne’s old life. As a showrunner at Kellynch, he initially appears as a friendly colleague with ambition, and he positions himself as someone who values Anne’s skills.

But his behavior slowly reveals a troubling dynamic: he leans heavily on Anne’s unpaid intellectual labor, then offers her an under-credited job as if it’s generous. His casual “date” framing and later lowball professional offer show how easily he blurs admiration with entitlement.

Theo is not villainous in a dramatic way; he is the kind of charismatic opportunist who thrives because competent people like Anne doubt their own worth. By refusing him, Anne breaks a lifelong habit of accepting crumbs and calling them opportunity.

Theo’s role in the story is to test whether Anne will keep choosing safety through self-sacrifice—or finally choose herself.

Cricket Rowley

Cricket is chaotic, theatrical, and oddly generous, embodying a kind of messy freedom Anne both fears and needs. Her apartment is sensory overload—tapestries, beanbags, incense, K-pop posters—and her lifestyle is the opposite of Anne’s tidy instincts.

Cricket’s reckless streak peaks in her arrest and her dramatic framing of injustice, which shows her tendency to turn life into performance. Yet she is also genuinely loyal.

She offers Anne a room without hesitation and repeatedly tries to include her in the building’s social life. Cricket doesn’t provide stability, but she provides space: living with her forces Anne to loosen control, to accept imperfection, and to find comfort outside rigid plans.

In the end, Cricket is a reminder that life can be loud and unplanned without being meaningless, and her presence softens Anne’s edges in the way a true friend often does—by being wholly herself.

Ellis Rowley

Ellis Rowley is the Uppercross board president and listing agent, embodying New York’s blend of community politics and quiet power plays. He manages the co-op with a focus on appearances and control, pushing fast approvals and dismissing objections even when conflicts of interest are obvious.

Ellis is not deeply explored emotionally, but his function is important: he represents a social structure that rewards insiders and smooth talkers. Ironically, despite his bureaucratic nature, he becomes part of Anne’s chosen community through James and the rooftop gatherings.

His presence helps frame the Uppercross as both a real home and a microcosm of competing desires, where Anne’s past literally changes hands without her consent.

James Rowley

James is Ellis’s husband and one of Anne’s warmest sources of everyday kindness. He is playful, domestic, and emotionally attentive in a way many characters aren’t, whether he’s baking a surprise cake or teasing Anne into laughing.

James operates as a stabilizing friend inside a building full of eccentric personalities, and his easy rapport with Anne shows what healthy companionship looks like—supportive without demanding repayment. His invitation to Freddie and his comfort around both Anne and Freddie help normalize their reconnection, making him quietly essential to the emotional ecosystem of Uppercross.

Bev

Bev is blunt, sardonic, and surprisingly insightful, acting as a grounding voice in Anne’s life. She doesn’t sugarcoat reality—whether warning about the illegality of Cricket’s sublet or calling out evasive dating talk on the rooftop—but her bluntness comes from care, not cruelty.

Bev’s key emotional role arrives when she tells Anne there isn’t a single “right choice,” a simple statement that cuts through years of Anne’s perfectionism. In a story about delayed love and second chances, Bev stands for practical wisdom: you make a life not by finding flawless paths but by committing to the one you want.

Glen

Glen enters as Cricket’s lawyer and romantic interest, but his personality suggests steadiness beneath the surface. He is calm, competent, and quietly protective—exactly the kind of person Cricket is drawn to when chaos catches up with her.

Glen’s presence also highlights Cricket’s vulnerability; her dreamy attachment to him suggests she craves someone who can anchor her without trying to restrain her. Though secondary, he adds a note of adult consequence to the story, reminding the reader that the building’s whimsical energy still exists within real legal and emotional stakes.

George Knightley

George is Freddie’s longtime friend and a quiet moral ally. He’s the kind of friend who can tease Freddie at a driving range but also point him back toward his core values.

George sees through the “job interview lunch” with Mark Segel and encourages Freddie’s nonprofit idealism, which helps Freddie find his way back to purpose. Importantly, George doesn’t push Freddie toward Anne in a sentimental way; he supports Freddie’s autonomy, believing that love should follow truth rather than nostalgia.

His steadiness provides Freddie with a model of grounded masculinity that balances ambition with conscience.

Will Darcy

Will Darcy’s role is smaller, but he rounds out Freddie’s world as part of a male friendship trio shaped by humor and candor. He participates in the teasing that lets Freddie vent without collapsing into bitterness, which keeps Freddie socially tethered during a period when he could easily drift into isolation.

Will’s presence reinforces that Freddie is not a lone romantic hero but a person embedded in loyal friendships.

Mark Segel

Mark Segel functions as the ideological antagonist to Freddie’s vision. As CEO of AirSoil, he is glossy, status-driven, and eager to turn sustainable technology into luxury branding.

Mark’s pitch reveals a worldview where innovation exists to serve power and wealth first, with moral language used as marketing. Freddie’s rejection of Mark is a turning point because it proves Freddie has not allowed success to hollow him out.

Mark therefore symbolizes the seductive compromise Freddie must refuse to remain himself.

Denise Sinclair

Denise Sinclair is flamboyant, self-mythologizing, and emblematic of reality TV’s performative appetite. Her filmed fight with Marsha triggers the collapse of Divorce Divas, and her Thanksgiving spectacle shows how she thrives in chaos without caring much about collateral damage.

Denise’s obsession with “content” makes her a human representation of the industry’s exploitation—she moves on to Theo’s new project while the crew sits unemployed. For Anne, Denise is a harsh reminder of what her work life has cost her: emotional burnout in service of someone else’s drama.

Marsha Beaumont

Marsha is less present on the page, but her legal action after the violent fight signals the volatility at the heart of Divorce Divas. She represents the moment when performance becomes consequence, forcing the show—and Anne’s life—into abrupt uncertainty.

In narrative terms, Marsha is the spark that makes Anne’s old world collapse, clearing space for the new one.

Birdie Carrington

Birdie is Freddie’s exuberant realtor, and she brings comic brightness to his homecoming. Her enthusiasm and quick intimacy contrast with Freddie’s exhaustion, making her a reminder of the city’s relentless energy.

She also serves as the agent of fate: by showing Freddie the Uppercross apartment, she unknowingly places him back into Anne’s orbit. Birdie is a small but pivotal force in the machinery of coincidence that drives the plot.

MacKenzie

MacKenzie, Walter’s much younger ex-wife, is a brief but impactful presence. Her legal claim to half of Walter’s assets and her intention to sell the apartment reveal that she is pragmatic and unwilling to protect Walter from the consequences of his own irresponsibility.

Though not deeply explored emotionally, she represents a boundary Walter never learned to respect, and her actions catalyze the upheaval that pushes Anne into transition.

Harold Vernon

Harold Vernon is Walter’s longtime lawyer and the voice of hard reality in the Elliot family. His job is to name what Walter refuses to face: the debts, the lack of savings, the inevitability of moving.

Harold’s role underscores how far Walter’s fantasy life has drifted from solvency and how much Anne has been carrying. He is less a character arc than a narrative instrument of truth.

Themes

Love, Timing, and the Weight of Unspoken Feelings

Anne and Freddie’s relationship in Anne of Avenue A is shaped less by a lack of love than by the timing of their lives and the things they never say out loud. Their breakup at the Half Pint isn’t a dramatic collapse of affection; it’s a collision between two futures that arrive too early and too suddenly.

Anne hears Freddie’s Argentina plan as a destabilizing leap, while Freddie hears her Columbia acceptance as a betrayal of shared dreams. What hurts most is not the choices themselves but the secrecy and the assumptions: Anne assumes Freddie will abandon his ambitions for her if she doesn’t intervene, and Freddie assumes Anne’s hesitation means she doesn’t believe in them.

Eight years later, the love is still alive, but it’s layered under pride, silence, and the habitual self-protection of adults who once got burned. Their reunion shows how love can persist in small artifacts—folded notes, remembered freckles, an old napkin in a wallet—while still being trapped by unresolved meaning.

The building setting forces proximity, but emotional closeness only returns when both characters learn to interpret the past with more generosity. Freddie’s late realization that Anne let him go out of care reframes years of resentment, and Anne’s admission about the fake Instagram reveals how devotion can survive even when contact doesn’t.

The story argues that love isn’t only about intensity; it’s about readiness and communication. When they finally reconcile, it happens because they stop treating love as a feeling that should magically align with life plans and start treating it as something chosen again, with full knowledge of risk.

Their happy ending doesn’t erase time lost; it acknowledges it, showing that love can be real, wrong-footed, delayed, and still worth returning to when the people involved finally grow into the same moment.

Ambition, Risk, and Competing Visions of a Good Life

From the first party scene to the final proposal, ambition is portrayed as both a compass and a battlefield. Anne’s ambition is orderly, credentialed, and defensive.

She sees security as a moral stance, not just a preference, shaped by her mother’s expectations and her father’s instability. Freddie’s ambition is restless and values-driven: he wants purpose, travel, and work that feels meaningful, even if it’s uncertain.

Their early fight shows how two ambitious people can still be misaligned because they define success differently. Anne doesn’t reject adventure because she lacks courage; she rejects it because she has absorbed a worldview where unpredictability equals danger.

Freddie doesn’t reject planning because he’s careless; he rejects it because he fears getting stuck in a life that looks impressive but feels empty. Both are partly right, and both are partly trapped by their own narratives.

The eight-year gap intensifies the contrast. Anne’s MBA and corporate pathway deliver competence, but not fulfillment.

Freddie’s hydroponics triumph delivers wealth, but also exhaustion and a subtle loss of self as corporate demands swallow the idealism that started the company. Their later arguments re-run the same philosophical split, now with adult stakes: Anne is still wary of giving up stability, and Freddie is still allergic to compromise that sells out his values.

What changes isn’t that one person “wins” the argument, but that each realizes ambition without self-knowledge can become a cage. Anne chooses Eufloria not because she suddenly stops being practical, but because she discovers a version of practicality that includes joy and personal ownership.

Freddie turns down AirSoil’s luxury branding because he returns to his original mission. Anne of Avenue A suggests that ambition should not be measured only by prestige or scale, but by alignment with who you want to be.

Risk becomes acceptable not when it disappears, but when it serves a life that feels yours.

Family Influence, Emotional Inheritance, and Breaking Old Patterns

Family in Anne of Avenue A functions like a silent partner in every major decision. Anne’s parents are not background figures; they are forces shaping her reflexes.

Walter’s financial recklessness and vanity create a childhood lesson that security can vanish overnight, pushing Anne toward control and caution. Bianca’s glamorous distance and constant opinion-making teach Anne that love is conditional on achievement and appearances, and that approval must be earned.

These influences don’t make Anne weak; they make her vigilant. Even as an adult, she is still doing emotional accounting for her parents’ chaos—fixing Walter’s messes at work, absorbing Bianca’s assumptions about what counts as a respectable life, and carrying a sense that stability is her job.

Freddie’s family offers a different inheritance. His parents’ home in Queens is imperfect but grounding, a place where he can garden, be teased, be tired, and still belong.

Sophie’s messy divorce and business struggle add another layer: the Wentworths are not idealized, but they model resilience and second chances rather than image management. The story traces how emotional inheritance can dictate romantic behavior.

Anne breaks up with Freddie partly because she’s internalized a caretaker role; she believes she must protect others from sacrifice, even if it costs her. Freddie reacts by cutting contact because he’s learned self-reliance and pride, not negotiation.

Their eventual healing requires both to step outside family scripts. Anne quits her father’s company in a moment of clarity: she refuses to keep paying for his irresponsibility with her own life.

That act is not just career-related; it’s an emotional boundary she never set before. Bianca’s later visit to Eufloria is equally important.

Her unexpected pride allows Anne to reframe her mother not as an unchanging judge, but as a person capable of growth. Freddie, for his part, listens to his father’s blunt advice to apologize and decide what differences matter.

Instead of repeating old defensiveness, he chooses humility. The theme here is not that family determines destiny, but that it sets defaults.

Anne of Avenue A is about noticing those defaults, questioning them, and choosing differently.

Home, Displacement, and Building a Life That Fits

Physical spaces in Anne of Avenue A carry emotional meaning, especially the Uppercross building and Anne’s childhood apartment. Losing that apartment is more than a real-estate event; it’s the collapse of a fragile identity Anne maintained for herself.

She has been living in the place that symbolized continuity while the rest of her life stayed in limbo. When Walter sells it, she’s forced to confront how little control she truly had and how much of her stability was borrowed from a past she can’t keep.

Her move into Cricket’s cluttered room feels like a step backward, but it also becomes a clearing point. The cramped, windowless space reflects her internal state: capable, exhausted, and trapped in other people’s decisions.

Freddie buying the apartment without knowing is almost cruelly symbolic. He wants a home base, something rooted after years of travel, and he chooses hers by accident—bringing their unresolved past into the literal walls around them.

His instinct to repaint and “erase traces” shows how home can be both refuge and reminder. For Anne, home shifts from a fixed place to something she must actively create.

Cleaning Cricket’s apartment, buying a battered Christmas tree, and putting up lights are small gestures of claiming space in conditions she didn’t choose. The flower shop becomes the larger version of that act.

Eufloria is not just a business; it is a home she builds with intention, community, and personal stake. The launch party shows her surrounded by people she chose rather than people assigned by history.

In that sense, home becomes relational and self-authored. The theme argues that displacement can be terrifying, but it can also strip away false shelters.

By the end, Anne and Freddie are not returning to the old apartment as the center of their lives; they are moving toward a new shared home built on honesty, purpose, and mutual respect. In Anne of Avenue A, home is not where you came from, but where you decide to belong.

Self-Worth, Being Valued, and Learning to Stop Settling

Anne’s growth is tied to a long, quiet struggle for self-worth. Early on, she measures her value by competence and usefulness.

She is the reliable one at Kellynch Productions, the fixer of crises, the adult in her parents’ orbit. That identity makes her strong, but it also makes her easy to exploit.

Walter relies on her labor without offering respect, and Theo relies on her expertise while keeping her officially small. Her initial reaction to Freddie’s Argentina plan shows the same pattern: she assumes responsibility for preventing sacrifice even though it’s not solely hers to manage.

Over time, this habit becomes settling—accepting less credit, less security, less joy, because she believes her role is to stabilize other people’s lives. The turning point at Thanksgiving is crucial.

Anne sees Walter celebrating money while the crew suffers and Denise hunts for “content,” and she finally refuses to be the invisible engine of someone else’s success. Quitting is a self-worth decision before it’s a career decision.

Her later meeting with Theo repeats the test. He offers her a job that is structurally smaller than the work she has been doing, confirming a dynamic where her contributions are assumed but not honored.

Anne’s refusal is not impulsive rebellion; it’s the first time she chooses her own value over proximity to prestige. Bev’s line about there being no single right choice lands because Anne has been waiting for external permission to pick the “correct” life.

When she chooses flowers, she chooses a life where her work and identity match. Freddie faces a parallel arc.

His corporate exhaustion comes from watching his ideals get priced and packaged. The AirSoil pitch is a moment where self-worth is tested through values: does he accept a powerful role that betrays his mission, or does he honor the thing that made him feel alive?

He chooses the latter, reclaiming respect for himself. Their reconciliation is partly romantic, but also about mutual valuation.

Freddie’s letter admits regret and commits to hard conversations; Anne runs through snow because she understands she deserves a love that stays and works. Anne of Avenue A frames self-worth as something practiced in decisions—choosing to be paid fairly, loved clearly, and recognized fully.

Forgiveness, Accountability, and Second Chances Without Erasing the Past

Second chances in Anne of Avenue A are not treated as simple rewinds. The eight-year separation is real damage, and the story doesn’t pretend otherwise.

When Anne and Freddie reunite, the attraction is immediate, but repair is not. Their post-Thanksgiving argument shows how old wounds survive in adult vocabulary.

Both are still keeping score: Freddie resents being left without a fight; Anne resents being punished with silence and blocked numbers. Accountability enters when they stop using the past as a weapon and start using it as information.

Freddie has to admit that his bitterness became a choice, not just a reaction. Blocking her number and staying angry for years may have felt self-protective, but it also froze him.

Anne has to admit that her control and secrecy hurt Freddie in ways she minimized. She didn’t only “set him free”; she decided for both of them.

Forgiveness becomes possible when motives are clarified. Bianca telling Freddie the truth is not a cheap plot fix; it’s the missing context that allows him to see love inside what looked like rejection.

Anne, meanwhile, sees Freddie’s idealism is not immaturity but integrity, and she sees how her own fear shaped the rupture. Their second chance comes with conditions: they promise to face differences instead of pre-deciding outcomes.

Importantly, the story doesn’t require either to become a different person. They don’t reconcile because Anne turns into a spontaneous traveler or Freddie turns into a risk-averse planner.

They reconcile because they accept the enduring parts of each other and choose which differences they can live with. The final proposal lands because it is rooted in history, not denial of it.

The first paper triangle is a relic of who they were, carried forward into who they are. Forgiveness here is not forgetting; it’s letting the past stop being a courtroom and start being a shared story.

Anne of Avenue A suggests that second chances are earned through honesty, clarified intent, and the courage to love someone again with open eyes.