Atlas of Unknowable Things Summary, Characters and Themes

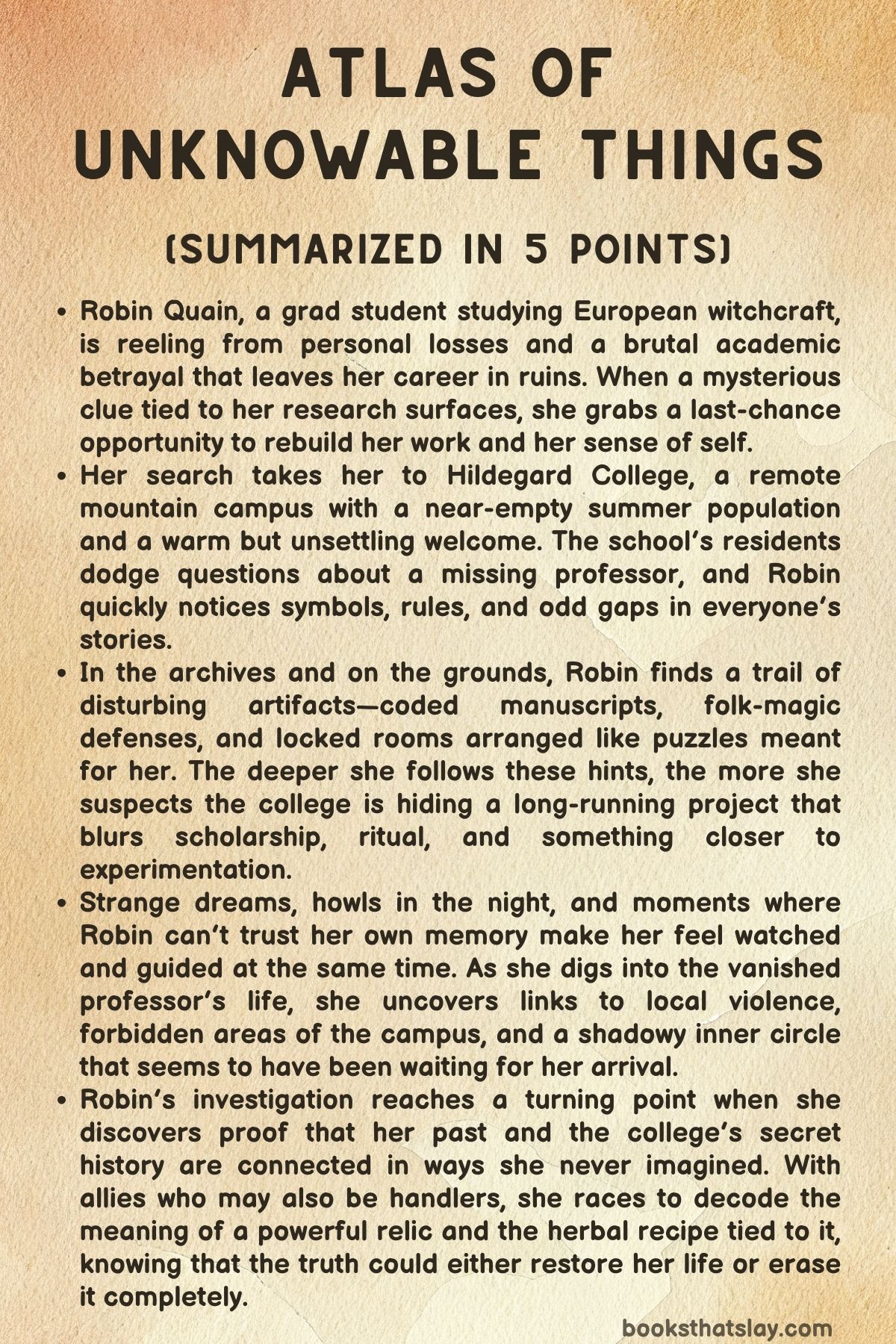

Atlas of Unknowable Things by McCormick Templeman is a literary horror novel about scholarship, betrayal, and the fragile border between rational inquiry and the supernatural. It follows Robin Quain, a graduate student whose academic life collapses after a trusted colleague steals her research on European witchcraft.

Searching for proof that could restore her career, Robin accepts a summer residency at remote Hildegard College in the Colorado Rockies. There, amid vanished professors, sealed-off islands, and unsettling folklore, her investigation becomes a dangerous test of memory and identity. The book blends campus mystery with occult history and psychological disorientation.

Summary

Robin Quain, a doctoral student studying European witchcraft, begins writing what was meant to be a private journal but turns into a record of obsession and dread. Her research centers on the witch-cult hypothesis: the idea that medieval witch trials targeted the remnants of an ancient fertility religion linked to Diana and Janus.

Robin starts from a place of grief and ruin. Her dog Kant dies, her boyfriend leaves and throws her out of their Red Hook apartment, and she is still reeling from a professional betrayal by fellow student Charles Danforth.

With nowhere to go, she moves into her cousin Paloma’s father’s rent-controlled townhouse in the East Village while her uncle is away. Paloma paints quietly; Robin tries to salvage her dissertation and her life.

Robin recounts the moment her project shifted from routine archival work to something that might overturn the field. She uncovered a set of letters between Joan of Arc and Gilles de Rais that referenced a secret religious practice and a ritual ointment.

Charles Danforth, charming and ambitious, befriended her during this breakthrough. They drank together, argued theory, and he offered to collaborate.

Trusting him, Robin showed him every note and lead. Charles then took her discoveries, reframed them as his own, and produced a celebrated dissertation.

He graduated with honors, got a publishing deal and a tenure-track job, while Robin’s academic future cratered. Rage and depression nearly consume her until a sharp-tongued colleague, Danica Felton, pushes her to fight back by writing a dissertation so airtight it would eclipse his.

Robin returns to work with a vengeance.

Her renewed research stalls on a frustrating detail. One Joan–Gilles letter lists ointment ingredients—aconite, angelica, and a strange herb called sangdhuppe—that Robin cannot identify in any pharmacopoeia.

She also can’t locate enough Rouen execution records to test the claim that accused witches died in groups of thirteen. Looking for modern echoes of old patterns, she reads a news report about Sabine Étienne, a young woman killed in a Rocky Mountain village where locals whisper that a werewolf did it.

Robin shows Paloma the article and photo. That night Paloma behaves unnervingly, drifting toward the door with a blank, hostile expression.

When Robin grabs her arm, Paloma says, “I know what you are,” and leaves. She returns later subdued and distant.

Robin digs into the Colorado story and finds another case: Dr. Isabelle Casimir, a Hildegard College scientist who vanished three weeks after Sabine’s death. A blog interview with Casimir mentions a relic excavated in Essex near Cressing Temple—a sculpture of thirteen women in a ring around a two-faced central figure.

Robin reads this as a coven around Janus and becomes convinced the relic could validate her thesis and ruin Charles’s claim. Hildegard also has deep manuscript archives and a summer residency.

Robin emails the head librarian, Dorian Dubois, applies, and is accepted almost instantly.

Meanwhile Paloma grows erratic, performing odd rituals around the townhouse and denying them afterward. Robin finds an unsent computer draft describing kidnapping, memory theft, and “Terrible Ones.” She schedules Paloma a psychiatric appointment, but Paloma disappears before it happens, leaving only a note saying she went to California.

Alone, Robin feels watched. She hears whispers in empty hallways, discovers unfamiliar symbols in her notes, and senses that something is sliding out of place in her mind.

She leaves New York for Colorado.

Hildegard College stands high in the Rockies, reached through a French-speaking enclave by a wary handyman named Jim. The gates bear a heart motif Robin sees but Jim claims not to, along with a French warning that outsiders should learn or stay silent.

The campus is a secluded Gothic compound with an old monastery turned into a library. Dorian welcomes her warmly and notes that Casimir recently “left.” He insists Casimir worked in cognitive neuro-programming, not archaeology, which clashes with the blog Robin read.

Robin meets Lexi Duarte, a behavioral psychologist; Finn Jeon, a systems scientist; and Aspen Thomas, the horticulture director. They are friendly but guarded, especially when Casimir is mentioned.

Robin spots occult-leaning symbols on campus, and her first nights bring white lights in the woods, animal howls, sleep paralysis, and a compulsive walk toward Casimir’s locked cabana.

Robin moves into Casimir’s former cabana and searches for the relic. She finds only expensive clothes and a locked basement stair.

Inside the basement she discovers hundreds of colored glass bottles hanging and standing in perfect concentric circles, their mouths aligned like a ritual instrument. The group reacts sharply when she mentions them.

The next morning the bottles vanish, and everyone claims the staff must have removed them. Robin’s dreams grow stranger; one features Charles warning her to “find the bluebird.” Another shows a horned, upright canine shape beside her bed.

A siren blares at night, and Aspen and Lexi insist Robin stay away from windows until it ends.

Robin begins scouring the grounds and nearby woods. She finds a fenced hollow around an ancient yew and hears Lexi summon Finn to discuss “the harvest.” Before dawn she follows flashes into the forest and sees a grave marked “Isabelle Casimir” with a horned god symbol.

When she brings Lexi and Dorian back, the grave is gone and they say she imagined it. Determined, Robin digs at the site and uncovers a burlap-wrapped baby doll holding a brass key and a note from Casimir: the relic is real, the danger is real, and Robin must be careful.

A stressed word in the note leads her to an anagram pointing to stained glass. The key opens a hidden storeroom filled with Casimir’s boxes and a bee-carved case containing divination cards and metal tiles.

Aspen later brings an herbalist journal suggesting sangdhuppe is a coded phrase for “blood of the hoopoe,” tied to extinct silphium.

Finn eventually tells Robin the blog post that drew her here was planted to lure her, and that Hildegard manipulates perception and memory. Robin disobeys orders and swims to the forbidden island.

There she finds a lantern-lit clearing with a marble pillar and a field of silphium, plus a domed stone office stocked with occult books. Solving a cipher on a blue desk, she uncovers The Book of Widows and a photo in which a maid is unmistakably Paloma, proving Paloma was at Hildegard long before Robin arrived.

Robin also finds dried blood around the pillar and, diving in the lake on the way back, discovers a massive metal grate under the “bottom,” like a cage keeping something down below.

Pressing harder, Robin is summoned to the island by the group. They force her to drink a bitter herbal mixture before speaking, then claim the mountains are inhabited by ancient forces and that they practice alchemy to contain a growing breach.

Robin panics, has a vivid vision of an enormous Greek-style temple in the woods, and wakes alone at dawn clutching The Book of Widows. She decides to flee, but her phone and laptop vanish and the campus empties out.

When she tries to escape with a delivery driver, Guillaume Étienne, he attacks her, calling her a witch and demanding to know where his sister Sabine is. Robin runs into the forest, reaching the same temple from her vision.

As her memories begin to unlock, Robin realizes she is not Robin at all but Isabelle Casimir, wiped and rebuilt. She breaks into a hidden chamber full of bottle circles and an altar lined with ritual objects.

There she finds the relic: thirteen warped figures around a horned, two-faced form. She takes it, then follows the chain of clues her former self arranged.

The dream of “bluebird” leads her to Charles’s old office, where she finds a key and a binder labeled Project Bluebird. Reading it restores her scientific past: she and Charles engineered a hippocampal prosthesis and used deep brain stimulation to cut and rewire memory.

Sabine Étienne, whose photo matches Paloma, was a test subject. Notes reveal that Jim is actually Uta Hopper Symon, Hildegard’s CFO, surveilling her.

Finn admits he orchestrated Isabelle’s clue trail like a controlled game to coax her into remembering safely. He brings her beneath the temple into an underground observatory.

There, tanks of deep blue liquid hold newborn, manatee-like beings; the liquid is a channel to another world. Hildegard harvests a ferromagnetic alloy from these creatures to enhance technology, including the prosthesis.

The barrier between worlds is failing, and Isabelle must restore the access method—now a retinal scan.

Using The Book of Widows as a coded recipe, Isabelle and Aspen map its symbols to herbs. She crushes the relic and finds a hidden scroll listing the true ingredients, including silphium disguised as hoopoe’s blood and licorice root to counter aconite.

Isabelle drinks a brewed tea that triggers full memory recovery. She remembers that the Terrible Ones depend on silphium, that she and Charles cultivated it and upset a natural cycle, and that during a breach she pushed Charles in panic, killing him against a marble pillar.

Overcome with guilt, she let Symon erase her mind.

When Subaru’s confession is overheard, Dorian tries to poison Isabelle, is exposed, and reveals he serves forces that want the breach widened. In the observatory he sabotages the controls and is dragged into the blue channel, devoured by predators from the other side.

With the system ruined, Isabelle insists on sealing the breach manually through an ancient underwater passage beneath the island. Aspen, Lexi, and Finn accompany her.

Isabelle dives into the otherworldly gate, repairs and caps it, and is chased back by something vast. She emerges in dark woods and meets Charles, now a ferryman-like presence.

He tells her it’s time. Taking his hand, Isabelle steps with him into the void, leaving the world she both saved and shattered behind.

Characters

Robin Quain / Dr. Isabelle Casimir

Robin is introduced as a graduate student whose intellectual life and personal life collapse at the same time, and that double-rupture shapes everything she becomes. Her project on the witch-cult hypothesis begins as a sincere academic attempt to recover suppressed histories, but the theft of her work by Charles turns scholarship into something like self-rescue: research becomes the only way to restore dignity, agency, and coherence.

At Hildegard, her skepticism and atheism stand out as a kind of psychological armor; she keeps insisting on rational explanations even as the environment sabotages her senses, because believing in the occult would mean surrendering the last stable part of her identity. The novel’s central twist—that Robin is actually Isabelle with an erased and re-scripted memory—retroactively clarifies her “unreliable narrator” quality: her voice is fractured not as a trick but as a symptom of being a person built from gaps, planted clues, and forced amnesia.

Her arc is thus less about discovering a secret world than about reassembling a self, and the final sacrifice reads as a tragic act of responsibility: once she remembers her role in the breach and Charles’s death, she chooses repair over survival, stepping into the void not in defeat but in an earned, devastating clarity.

Paloma Quain / Sabine Étienne

Paloma begins as Robin’s artistic cousin and safe harbor—someone grounded in paint, routine, and domestic intimacy while Robin’s academic life spirals. Her early oddness in the townhouse, the draft about “Terrible Ones,” and her sudden disappearance position her as a haunting riddle, but the later reveal that Paloma and Sabine are the same person reframes her entirely.

She becomes the living evidence of Hildegard’s experiments: a human being whose identity has been overwritten, who carries trauma in her body before she can articulate it, and whose behavior oscillates between fragile normalcy and flashes of terrified knowing. Paloma’s whispered “I know what you are” isn’t mystical insight so much as the spillover of buried memory recognizing a fellow victim.

She functions emotionally as Robin’s mirror—showing what mind-theft does to a person—and structurally as the breadcrumb trail that pulls Robin toward Hildegard. By the end, Paloma/Sabine embodies the novel’s cruelest theme: that institutions can erase a life so thoroughly that even the victim’s name becomes part of someone else’s puzzle.

Charles Danforth

Charles is both the mundane villain of academia and the supernatural hinge of the later plot, which is why his presence feels like a shadow across the whole book. At first he represents a familiar kind of betrayal—charming collaborator turned thief—using Robin’s trust to elevate himself while burying her career.

His dismissal of Robin as “hysterical” exposes his core strategy: he maintains power by defining other people’s reality for them. When the story deepens, Charles is revealed as a brilliant but ethically hollow scientist who helped create the memory-rewriting technology and the silphium project; the earlier academic theft becomes a smaller version of a lifelong practice of extraction.

Yet his arc isn’t flatly monstrous. In death he becomes a ferryman figure, a liminal guide beyond the breach, suggesting that whatever he was in life, he remains bound to the consequences of their shared work.

He is the embodiment of the book’s moral paradox: a man capable of tenderness and partnership, yet willing to destroy others and the world’s boundary for discovery and status.

Danica Felton

Danica appears briefly compared to Hildegard’s circle, but she matters because she is the only early relationship that offers Robin something like healthy confrontation. Her wit and blunt encouragement push Robin out of paralyzing grief and rage into action, but crucially, she doesn’t romanticize revenge; she channels Robin’s fury back into competence.

Danica therefore represents an ethical counterpoint to Charles: where he steals Robin’s mind and work, Danica returns Robin to herself by insisting she still has something worth defending. Even after Hildegard’s manipulation begins, Danica’s earlier voice lingers as a psychological anchor—proof that Robin once had a world where reality wasn’t constantly negotiated by hostile forces.

Dorian Dubois

Dorian enters as the gracious librarian-host, almost a Gothic archetype of the cultured gatekeeper, and he keeps that mask for long enough to be genuinely disorienting. His warmth, his careful attention to Robin’s comfort, and his willingness to discuss belief create a sense of intimacy that makes his later betrayal feel not just dangerous but personal.

Dorian’s worldview is steeped in the spiritual and the symbolic; unlike Robin, he doesn’t need proof because he experiences the grounds as already inhabited by moral and metaphysical forces. That devotion makes him the most ideologically committed antagonist: he isn’t exploiting the breach for power or curiosity so much as serving an opposite “side.” When exposed, he reveals the quiet fanaticism underneath his civility, showing how easily care can be weaponized.

His end—being dragged into the blue expanse and devoured—fits his role as a man who chose cosmic allegiance over human solidarity, and who finally meets the reality he claimed to understand.

Finn Jeon

Finn is the novel’s most slippery figure until the reveal, functioning as flirt, skeptic, provocateur, and co-conspirator in equal measure. His surface persona—weed-smoking systems scientist with a casual attitude toward authority—helps Robin feel she has an ally outside the campus’s stiff formalities, but he is also one of the architects of her controlled awakening.

What makes Finn compelling is that his manipulation is not purely predatory; he frames the clue-trail as an alternate-reality game designed to protect Robin/Isabelle from the shock of direct revelation. That logic is ethically gray: it treats her autonomy as secondary to what he believes is her survival, echoing the broader institutional paternalism of Hildegard.

Still, Finn is not aligned with Dorian’s destructive agenda. He is desperate to fix the failing barrier and needs Isabelle’s memory as the missing key, which makes him a portrait of someone trying to do right inside a system built on wrong.

His affection for Isabelle feels real, but it’s always braided with need, and that tension defines his character.

Aspen Thomas

Aspen is presented as the horticulture director, a caretaker of plants and remedies, and her connection to the apothecary garden makes her the story’s bridge between science and folk magic. She is often the first to supply practical help—offering tea, sharing the herbalist journal, assisting with the final potion—and that nurturer role initially reads as benign.

Yet her guardedness, her sudden coldness, and her participation in coercing Robin to drink the “medicine” reveal a harder edge: Aspen protects the group’s secrets with the same attention she gives her plants. Her deepest significance lies in her knowledge of coded ingredients and her ability to interpret The Book of Widows as both grimoire and recipe.

In the end she becomes one of the survivors working to repair the breach, suggesting that her loyalty is not to cruelty but to containment and continuity, even if she has long accepted unethical costs as the price of keeping the mountains “quiet.”

Lexi Duarte

Lexi plays the role of approachable guide at Hildegard, giving tours, offering Robin the bungalow, and behaving like the most socially normal member of the circle. That normalcy is itself part of the trap: she is the face of institutional friendliness, smoothing over forbidden zones and unexplained absences with calm reassurance.

As a behavioral psychologist and someone who grew up on the grounds, Lexi understands the mechanics of influence, memory, and compliance, which is why her presence around Robin always carries an undertone of soft control. Her reactions—especially when Robin begins to remember—suggest internal conflict, as if she is both frightened of what Isabelle might uncover and frightened for her.

Lexi thus embodies the banality of complicity: she doesn’t need to be cruel to help something cruel continue, because her expertise makes subtle coercion feel like care.

Jim / Uta Hopper Symon

Jim arrives as a minor, vaguely hostile handyman, an outsider-within-the-system who seems more superstition than threat. The reveal that he is actually Uta Hopper Symon, Hildegard’s CFO and a primary architect of the memory-erasure program, turns that early hostility into something chillingly purposeful.

Symon represents the administrative face of horror: not the zealot like Dorian, not the conflicted insider like Finn, but the managerial sponsor who makes experiments possible through money, access, and quiet oversight. His spying on Robin and his role in taking Isabelle to be erased show his belief that identity is a tool to be rearranged for institutional goals.

He is the human logic of Hildegard at its coldest—efficient, profit-minded, and fully willing to treat people as replaceable vessels.

Guillaume Étienne

Guillaume is initially a distant figure—Sabine’s brother in a Zoom call, a villager orbiting the campus’s mysteries—but when he appears in person he becomes raw grief in motion. His rage toward Robin, calling her a witch and demanding his sister back, is not irrational hysteria; it is what happens when official narratives erase a loved one and the only remaining explanations are folklore and fury.

Guillaume’s violence against Robin is ugly and wrong, but it springs from the same soil as the book’s central tragedy: people pushed into monstrousness by not knowing who has stolen their dead. He also serves as a reminder that Hildegard’s experiments don’t just mutilate subjects; they radiate harm into families and communities that never consented.

Jeanne Étienne

Jeanne carries the long memory of the region and functions like a living archive that rivals Hildegard’s manuscripts. Her stories about her grandfather cooking for secret elite parties, her old photographs, and her fierce insistence that Sabine might still be alive expose the campus as an intergenerational machine rather than a recent aberration.

Jeanne’s voice blends folklore with factual testimony, underlining the novel’s theme that “myth” is often the language left to people whose evidence has been systematically suppressed. Her distress at the end of the Zoom call conveys how unbearable it is to hold history when power refuses to acknowledge it.

Kant

Kant, Robin’s dog, dies early, but that death is not a throwaway tragedy. It marks the first rupture in Robin’s world and sets the tone of dispossession and loneliness that makes her vulnerable to Hildegard’s pull.

Kant symbolizes uncomplicated loyalty and the domestic life Robin loses; his absence is part of why she clings so hard to her work and later to the idea that meaning can still be excavated from ruins.

Themes

Scholarship as a form of hunger and self-destruction

Robin’s academic project in Atlas of Unknowable Things is not treated as a neutral career path; it behaves like a craving that reorganizes her life and then consumes it. From the moment her dog dies, her relationship collapses, and her home is taken away, research becomes the only structure she can cling to.

The manuscript she narrates makes clear that scholarship is also emotional shelter: it gives her a language for grief and rage when ordinary social supports fail. Yet the same work also pulls her into riskier and riskier terrain.

What begins as a dissertation about the witch-cult hypothesis turns into a personal quest for proof, vindication, and later survival, blurring the line between intellectual curiosity and compulsion. Her focus narrows until every symbol, rumor, artifact, and missing person looks like a key meant specifically for her.

This narrowing is not portrayed as heroic dedication. It is closer to addiction: it offers bursts of meaning, followed by deeper emptiness that only more research can temporarily fill.

The setting of Hildegard College intensifies this theme because the institution is itself a maze of archives, coded relics, and taboo knowledge. Robin is rewarded for pursuing answers but also punished for it by confusion, manipulation, and physical danger.

The story keeps asking what it costs to treat knowledge as personal salvation. In the end, the desire to “get it right” becomes inseparable from the desire to become whole again.

Scholarship is shown as a powerful tool, but also a hungry force that can hollow out the person holding it if they use it to replace love, safety, or self-trust.

Betrayal, humiliation, and the long shadow of revenge

The betrayal by Charles Danforth is the emotional engine that drives Robin long before the supernatural or scientific plot fully reveals itself. His theft of her work is not just professional sabotage; it is an assault on her sense of reality, because he rewrites their shared history into a story where her labor never mattered.

The way he dismisses her as hysterical and cuts her off echoes older patterns of silencing women, especially in intellectual spaces, and Robin’s spiraling anger grows from that humiliation. Her response is not quiet resilience; it is a wish to ruin him through superior scholarship, a form of revenge that still keeps her tethered to him.

Even after she arrives at Hildegard, memories of Charles intrude like a wound that will not close, and his voice appears in dreams and visions as both taunt and warning. The narrative suggests that betrayal reshapes time: it makes the past replay itself again and again, and it makes the future feel like a trial that must be won to correct what happened.

Later, when Robin learns she is Isabelle and that Charles is dead by her hand during the breach, the theme changes from revenge outwardly aimed at a rival to guilt inwardly aimed at herself. What she thought was a simple moral equation—he wronged me, I will defeat him—turns into a knot where love, collaboration, rivalry, and violence cannot be cleanly separated.

The story refuses to present revenge as healing. Instead, it shows how the desire to punish a betrayer can keep a person trapped inside the betrayer’s narrative, until they no longer know whether they are acting for justice, for ego, or for the simple need to feel powerful again.

Identity as a contested space shaped by memory

The most unsettling discovery in Atlas of Unknowable Things is not the relic or the otherworldly beings beneath the observatory, but the realization that “Robin” is a constructed self. The book treats identity less as a fixed core and more as a fragile agreement between memory, body, and environment.

Robin’s early disorientation—hearing whispers, finding symbols she does not remember drawing, sensing she is being watched—reads at first like psychological strain or supernatural influence. Over time, these experiences become evidence that her mind has been edited.

The hippocampal prosthesis and deep brain stimulation project show memory not as private property but as material that can be rearranged by institutions with enough power and secrecy. This raises an ethical horror: if memory can be rewritten, then the self becomes negotiable, and consent becomes meaningless unless the person can remember giving it.

Robin’s growing fear that others are manipulating what she sees and recalls is therefore not paranoia; it is a survival instinct in a world where those manipulations are real. The staged clues and puzzles set by Finn reinforce this theme in a gentler but still troubling way.

Even care is control when it decides what truth someone is “ready” to know. When Isabelle finally recovers the full story of who she is, including the death of Charles and her own choice to have her mind erased, identity becomes a moral burden.

Knowing herself means inheriting her past actions, and that knowledge cannot be undone without losing herself again. The final movement—stepping into the void with Charles—feels less like escape and more like the last consequence of a self rebuilt on missing pieces.

The book suggests that identity is not only who we are, but what we can bear to remember.

Closed communities, isolation, and the politics of secrecy

Hildegard College functions as more than a spooky campus; it is a model of how closed communities protect themselves. Everyone Robin meets belongs to the place in a familial, almost hereditary way.

They grew up together, share private histories, and speak in partial truths that mark her as an outsider. The physical terrain reinforces this social closure: high altitude, dense woods, forbidden paths, an off-limits island, locked doors, missing tools, and surveillance disguised as hospitality.

Robin’s isolation is both practical and psychological. She is far from her city life, her academic peers, and her cousin Paloma, and those absences make her more dependent on the small group who control what she eats, what she sees, and what she is told.

The community’s secrecy is presented as cultural tradition (“old ways” versus “new”), but also as a strategic defense of power. Knowledge at Hildegard is hoarded, performed through rituals, and released only under coercive conditions, such as the demand that she drink the foul medicine before being told the truth.

The villagers’ folklore about werewolves and the college’s denial of known events show how secrecy spills outward, shaping the wider region through rumor, fear, and selective forgetting. Even acts that look like kindness—giving her housing, tours, tea, companionship—are complicated by the possibility that they are also methods of containment.

The theme reaches a peak when Robin finds her devices missing and the campus suddenly empty, demonstrating how easily a closed system can erase someone’s link to the outside world. The book’s view of isolation is not romantic; it is political.

A sealed community can keep ancient dangers contained, but it can also create conditions where exploitation, experimentation, and disappearance become normal because there are no witnesses who are not already invested in the silence.

The ethical edge between science, belief, and exploitation

The narrative constantly tests the boundary between rational inquiry and the abuses committed in its name. Robin arrives insisting she is a skeptic and an atheist, committed to evidence.

Dorian counters with belief in angels, demons, and evil, and their conversations show that the issue is not whether belief is true but how belief is used. At Hildegard, scientific language and occult practice are not enemies; they are collaborators.

Isabelle and Charles’s neuro-programming work treats human memory as a system to be optimized, which leads directly to human testing on Sabine Étienne, the woman who is also Paloma. This is science without ethics: brilliant, ambitious, and casually violent.

At the same time, the group’s alchemical and ritual practices are not quaint superstition. They produce real effects because they are tied to ecological resources (silphium), otherworldly physics (the blue liquid channel), and technological power (the ferromagnetic alloy).

The story therefore refuses a simple “science bad, magic good” or “magic dangerous, science safe” split. Both are ways of reaching for control over life, death, and meaning, and both can slide into domination when unchecked.

The “harvest” of creatures from another world exposes the exploitative core of Hildegard’s project: knowledge and progress are funded by extraction from vulnerable beings who cannot consent. Even the attempt to fix the breach is morally mixed.

The goal is to protect humanity, but it relies on secrets, manipulation, and the expectation that Isabelle sacrifice herself. By staging the final repair as a literal dive into a channel between worlds, the book frames ethics as something that must be lived through risk, not solved by argument.

The question it leaves hanging is whether any pursuit of the unknowable can stay clean once it demands bodies, ecosystems, or minds as its price.

Women, erased histories, and reclaimed power

Women in Atlas of Unknowable Things are repeatedly positioned at the hinge between what is remembered and what is denied. Robin’s original research focuses on medieval witch hunts, a historical machine that targeted women’s bodies and knowledge while later historians often treated those victims as footnotes or fantasies.

Her impulse to prove an organized fertility religion is partly scholarly, but it is also a refusal to accept that women’s spiritual and social networks were only imaginary. The relic of thirteen women around a two-faced figure becomes symbolic of that struggle: women gathered in a circle, visible as a unit, not as isolated anomalies.

In the present-day plot, the same pattern repeats. Paloma/Sabine is abducted, used, and rewritten.

Isabelle allows her own mind to be erased in order to stop living with unbearable guilt, echoing how women are pushed to disappear when their stories threaten powerful men or institutions. Yet the book also tracks forms of reclaimed power.

Robin’s decision to continue her work after Charles’s theft is an early act of refusal. Isabelle’s eventual recovery of memory is another, because it brings back not only trauma but agency, including responsibility for Charles’s death.

The women-centered books, gardens, coded herb symbols, and “widows” archive signal a lineage of female knowledge that survives by disguising itself. Even the final choice to repair the breach, knowing it might cost her life, is framed as deliberate commitment rather than martyrdom forced on her by others.

The theme does not claim that women’s suffering automatically produces wisdom. Instead, it shows how systems repeatedly try to steal women’s labor, credibility, and even minds, and how the fight to reclaim those things is ongoing, messy, and sometimes fatal.