Blind Date with a Werewolf Summary, Characters and Themes

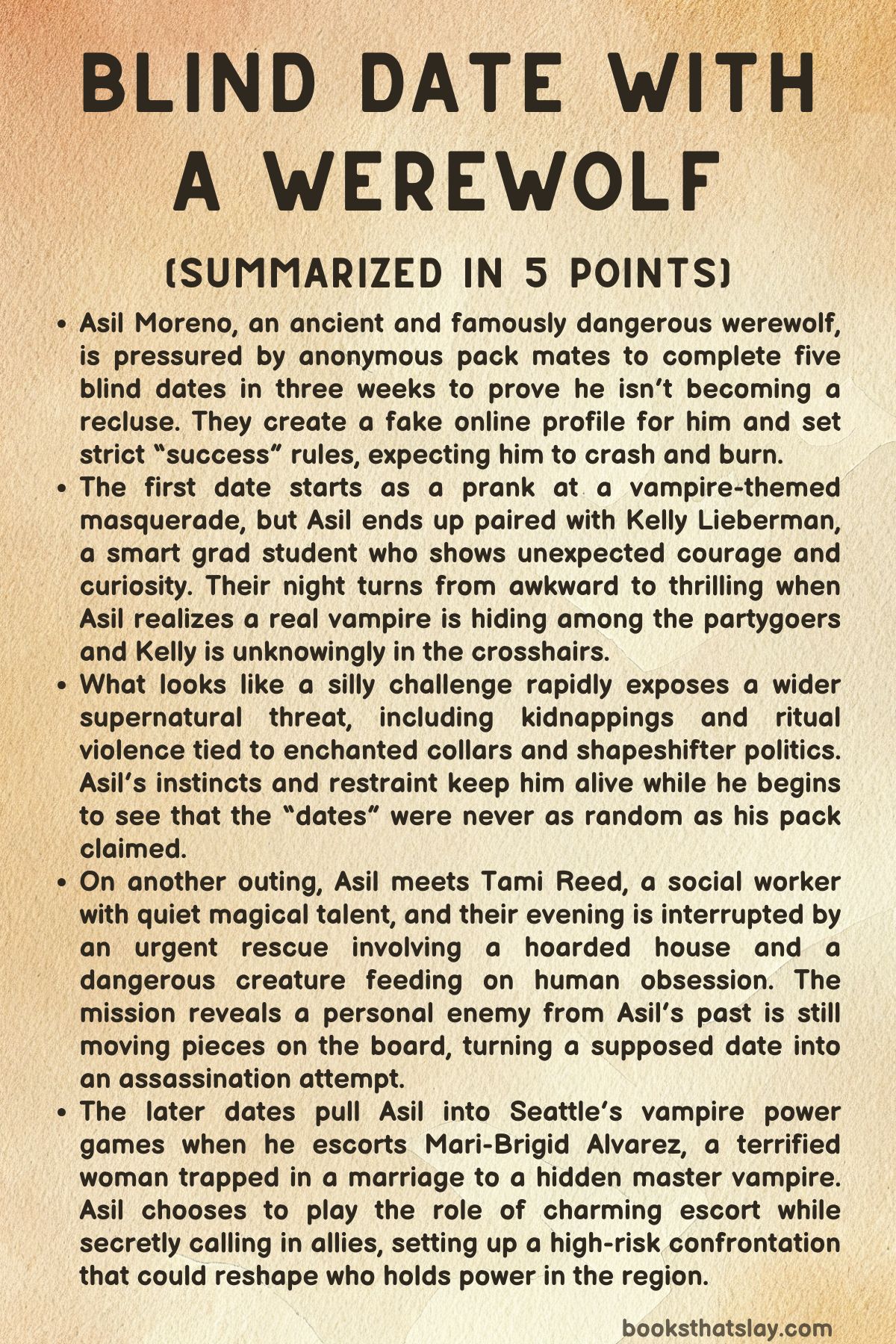

Blind Date with a Werewolf by Patricia Briggs is a fast, wry urban-fantasy novel set in her Alpha & Omega world. It follows Asil Moreno, an ancient, feared werewolf called the Moor, who is forced by meddling pack mates into a string of “blind dates” meant to pull him out of isolation.

What begins as a prank turns into a chain of supernatural crises involving vampires, witches, and fae politics. Through these chaotic nights, Asil’s loneliness, honor, and fierce restraint are tested, and an unexpected bond forms with Ruby, a half-fae ghost hunter carrying a deadly secret.

Summary

Asil Moreno, one of the oldest and most dangerous werewolves alive, receives an anonymous email from pack mates calling themselves his “Concerned Friends.” They claim he has become too cut off from others and issue a challenge: five dates in three weeks, all arranged through online profiles they created without his consent. The rules are half joke, half trap—each outing counts as successful only if nobody runs away screaming, nobody dies during the date, and Asil stays at least two hours.

A betting pool is already running on how quickly he will fail. Asil suspects which wolves are behind it, but instead of refusing, he accepts, partly out of curiosity and partly because he has little to lose.

The first date is with someone named “Kelly,” supposedly a woman from Missoula, and the plan is a winter vampire masquerade ball. Asil decides to meet for Thai food first, arriving with roses as a peace offering to an innocent stranger who thinks he’s been flirting online.

The situation turns upside down when the late, flustered “Kelly” shows up and is actually a young man. Mortified, Kelly explains that a friend set him up, expecting a humiliating prank, and he didn’t even have a way to cancel.

Asil handles the mistake with calm dignity, and Kelly, surprised by Asil’s patience and unreal beauty, chooses to stay so Asil won’t feel rejected. Over dinner, Kelly Lieberman, a 22-year-old toxicology grad student, proves clever, warm, and principled.

The evening becomes real rather than a gag.

Kelly won’t ride in Asil’s car for safety reasons, so Asil works around it by letting Kelly drive Asil’s Porsche to the hotel and taking a cab from there. Kelly’s nervous driving makes Asil quietly amused.

At the masquerade, Asil improvises a story that they’re a vampire and a werewolf pair as part of the theme; no one realizes they’re closer to the truth than anyone should be. Kelly is at ease in the costumed chaos, talking about role-playing games and dancing without embarrassment.

A friend of Kelly’s, Meg, arrives in a panic after speaking to her uncle Tag, a real werewolf, who warned that Asil is a legend and not safe to be near. Kelly refuses to bolt, trusting Asil’s steady presence.

They dance a tango and accidentally make a spectacle of themselves in a way that feels joyful for both. Then Kelly’s prankster friend Trace appears, smug that the setup worked.

At the same time, a newcomer named Bruce enters; to everyone else he’s an awkward college LARPer, but Asil recognizes the scent of a true vampire he once knew. Worse, Asil realizes Bruce has already bitten Kelly at some earlier time without Kelly understanding what happened.

Asil pulls Kelly aside, confirms the bite, and tells him quietly that vampires are real, enslave victims, and that Bruce is one of them. Kelly is frightened but keeps his head.

Rather than start a panic inside the ballroom, Asil and Kelly set a trap. Using Trace as bait for Bruce’s ego, they lure the vampire out into the winter woods.

There Bruce drops the friendly act and tries to hypnotize Kelly into servitude, revealing his bitterness and predatory hunger. Moonlight breaks through clouds, shattering the vampire’s control long enough for Kelly to resist and run.

Bruce gives chase, savoring fear like sport.

Kelly is driven back against a tree as Bruce shows his monstrous face. Kelly stalls him with daring talk, and Asil—already shifted into a lethal wolf—hits Bruce from the shadows.

The fight is savage and fast. Bruce is strong enough to slam Asil into trees, but Asil’s age and fury win; he tears off the vampire’s head and howls over the body.

Meg and Trace stumble onto the scene. Trace collapses in terror, and Meg freezes, trying to understand what she’s seeing.

Kelly, shaking but alive, bows slightly to Asil in instinctive respect and promises they will keep quiet and explain the danger to Trace. When Kelly looks up, Asil has already vanished into the night.

The “Concerned Friends” email again, gleeful that the first date counts as a success. They schedule another, then another, treating Asil’s life like a game.

The second outing goes disastrously wrong in a different way: it is a death-ritual ambush involving captive big cats and ritual killers. Asil survives without killing any living humans himself.

He frees an elderly lioness and a young tigress that had been enchanted and caged. When the dust settles, he stays in a remote Montana barn to guard them until help arrives.

The lioness is calm and affectionate, while the tigress is cautious and watchful. Asil arranges sanctuary for smaller animals and donates enough money to ensure the lioness will live comfortably at Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle.

Two tiger shapeshifters, Nura and her brother Hamza, arrive by helicopter. They explain the tigress, Zoya, is part of their extended family, stolen from South Asia where her line has been unable to shift for generations.

Nura shifts into tiger form to calm Zoya, then escorts her away. Asil keeps the remaining enchanted collar pieces, determined to find who ordered the kidnappings.

A collared male tiger who helped the plot is dragged down from hiding, and Bran Cornick—the Marrok, leader of North American werewolves—arrives. Asil hands Bran the captive as a “Christmas present,” warning that bigger supernatural forces are moving.

Bran takes the prisoner for interrogation. Before leaving, the lioness speaks mind-to-mind to Asil, revealing herself as an ancient, near-divine guardian who came hunting the same thieves.

She chooses retirement rather than more war.

For the third date, Asil meets Tami Reed, a Spokane social worker who thinks she is meeting a gardener. The dinner begins gently, with talk of plants and her work with homeless teens.

Then a frantic call comes from a client, Joshua, who says he and his little sisters are trapped in their hoarder mother’s house and smell smoke. Tami rushes to help, and Asil follows.

They force their way through a maze of filth and collapsing junk, freeing the children. Asil senses a supernatural serpent-creature feeding on the mother’s obsession with hoarding, and Tami confirms it.

They head into the basement to end it.

There, Tami betrays him. A hidden amulet twists her magic into something dark.

She is revealed as a weapon raised by Mariposa, a black witch tied to Asil’s past. Tami intended the emergency as bait and now tries to kill Asil using the entranced mother as sacrifice.

Joshua appears with a shotgun and shoots Tami dead. A young wyrm emerges and devours her body, but Asil gives his wolf full control and kills the creature swiftly with his sword.

He lets the house burn to erase proof, leaving the survivors safe and the supernatural traces gone. Furious, Asil warns his anonymous arrangers that their “background checks” are worthless.

The fourth date changes everything. Ruby, a half-fae ghost hunter living in a Victorian house, is waiting with her nervous werewolf friend Alan.

Alan arranged the meeting because Ruby is bound to a fae predator and needs help strong enough to survive what’s coming. Ruby doubts herself, convinced anyone she involves will die.

Alan calls to check Asil’s reputation and learns too late that Asil is the Moor. Panic rises, but before they can cancel, Asil arrives in the rain.

Inside, Asil quickly senses Ruby’s binding and that her captor is close. Ruby tries to keep the moment only about ghost hunting, but Asil’s quiet authority draws out the truth: she was bought as a child by a fae called Ivory Jim, tattooed with his blood, and magically geased to avoid powerful allies.

He feeds on her life and magic and tracks her through the tattoo. Ruby admits she tried to lure him here so Asil would be present, even though she didn’t want to risk him.

Ivory Jim arrives before she can say more. He claims Ruby as property and attacks Asil with cruel blue magic.

Dusty, the mischievous spirit of Peg’s dead twin, interferes just enough to break the fae’s rhythm. Ruby’s bound power finally snaps loose.

In a storm of raw force, steel knives form around her and drive through Ivory Jim, killing him. Asil steadies Ruby with a brief kiss that calms her spiraling magic, then helps remove the body using look-away magic so her human team won’t be destroyed by what they witnessed.

Ruby realizes Asil held back in the fight to give her the chance to free herself, not to rescue her like a helpless victim. She thanks him, invites him to dinner, and asks for another date.

Asil accepts, surprised to feel hope again.

Asil tries to refuse the final forced date, but circumstances pin him in Seattle during a huge storm, and strange powers push him toward the last appointment. He agrees under one condition: afterward he may send someone else on a date as a gift.

The final match is Mari-Brigid Alvarez, sent to a charity ball by her wealthy husband. Asil learns on the ride that the husband is a master vampire.

Mari-Brigid and her family servant-bodyguard Bobby are trapped in a system of cruelty: Alvarez forces her on dates with men he chooses, then murders the men if she doesn’t provide the lies he wants to hear. Bobby, bound by generations of service, cannot escape either.

Worse, Alvarez serves Bonarata, a rising vampire lord shifting power into the U.S.

At the ball, Asil plays the role of devoted escort while marking threats by scent. He draws attention to himself through bold dancing, then is led away to meet the hidden master.

He returns bloodied and exhilarated: he has exchanged blood with Alvarez, a risky tactic that overwhelms the vampire but also ties Asil to him. Asil keeps the bond so Alvarez will hunt him instead of Mari-Brigid and Bobby.

He rushes them to Ruby’s warded house, where werewolves and a witch defend them.

Asil chooses Woodland Park Zoo as the battlefield, near a lantern display that limits collateral damage. He kills a pack of elder vampires alone, taking vicious wounds.

Alvarez finally appears, taunting him and pinning him with bullets and a sword. Asil is seconds from death when the ancient lioness he once saved breaks her promise to stay out and crushes Alvarez, erasing his magic so he cannot rise again.

The bond snaps, freeing Mari-Brigid and Bobby. Asil staggers back to Ruby’s home as a battered, speaking wolf.

Ruby waits through the night terrified he is dead, then cradles his head when he returns. On New Year’s Eve, Asil and Ruby share a quiet meal while watching Kelly Lieberman on a safe, ordinary date Asil arranged as his promised gift.

The prank that started as mockery ends with Asil less alone, Ruby unbound, and several deadly powers removed from the world.

Characters

Asil Moreno

Asil Moreno, known as the Moor, is the gravitational center of Blind Date with a Werewolf. Ancient, courtly, and lethally competent, he carries the weight of centuries in a way that shows up as restraint rather than stiffness.

The dating challenge exposes one of his key traits: he is willing to play along with foolishness if it serves a purpose, whether that purpose is pack harmony, curiosity, or simply seeing what the world is putting in his path. His self-control is constant work—he monitors his temper, his wolf, and his capacity for violence like a man holding a storm behind his ribs.

Under the polished surface sits deep old grief, including the murder of his mate and the complicated scar of Mariposa’s betrayal, which makes him both wary of intimacy and quietly hungry for it. His moral code is sharp: he kills when necessary, protects the vulnerable without fanfare, and refuses to be commanded even by allies, yet he also gives gifts freely—donations for sanctuary, a zoo retirement for an old lioness, a second chance for Mari-Brigid and Bobby, and even a date for Kelly as repayment for decency.

Asil is not softened by age; he is refined by it, becoming a man who can tango in a masquerade, interrogate a conspirator, and walk into elder-vampire politics with the same calm, predatory clarity.

Kelly Lieberman

Kelly Lieberman begins as an accidental date and becomes a surprising measure of human courage. At twenty-two, he is witty, principled, and a little overwhelmed by the chaos he’s stepped into, yet he keeps choosing decency over safety.

His refusal to get into Asil’s car and his initial suspicion show practical intelligence, not cowardice. What makes Kelly stand out is his emotional steadiness: when confronted with the reality of vampires, he is shocked but not theatrical, and he listens, adapts, and follows a dangerous plan because it protects others.

His LARP background gives him a flexible imagination, but his bravery is real-world; he faces a predator, resists enthrallment, and survives by combining nerve with quick thinking. Even after witnessing violence that would break most people’s sense of reality, he remains generous—bowing to Asil’s wolf, promising discretion, and thanking Asil for the date instead of blaming him.

Kelly’s role is small in page time but big in meaning: he is proof that ordinary humans can be honorable in supernatural darkness, and the later glimpse of him dating Sherwood shows that Asil does not forget kindness.

Meg

Meg is the protective friend whose fear comes from knowledge, not melodrama. Her connection to the supernatural through her uncle Tag means she understands that the world behind the costume ball is real and lethal.

She reacts with panic because she believes she is trying to save Kelly’s life, and that fear is a form of love. What’s notable is that Meg listens when Asil speaks plainly; she doesn’t like him, but she recalibrates, stepping back once she believes Kelly is safe.

Meg embodies the thin line between the human social world and the hidden supernatural one, and her presence keeps the masquerade sequence grounded in real stakes.

Trace

Trace is the smug architect of the prank, a human catalyst for the story’s opening confrontation. His cockiness is less cruelty for cruelty’s sake and more the careless arrogance of someone who thinks the world is a stage for his jokes.

The moment things become real—blood, monsters, severed heads—Trace collapses instantly, revealing how shallow his confidence is. He functions as a contrast to Kelly: both are human, both are young, but where Kelly is brave and considerate, Trace is careless and self-serving.

His fainting at the corpse is a moral punctuation mark to his earlier swagger.

Tag

Tag, Meg’s uncle, is seen only through his warning, but that warning matters. As a werewolf aware of Asil’s legend, he is a voice of pack memory and caution.

His role underscores the hierarchy and danger within werewolf society: even among predators, Asil’s name carries the gravity of an apex threat. Tag’s protective instinct toward Meg and Kelly shows the pack’s social web extending into family ties and human friendships.

Bruce

Bruce is a vampire hiding in plain sight, doubling as a quiet horror in the ball sequence. His easy blending into human costuming highlights how predators exploit social camouflage.

The revelation that Kelly has been bitten before without realizing it makes Bruce a symbol of undetected violation rather than just a combatant. When he lures Kelly outside, his contempt for Christmas and priestly past give him a bitter, corrupted interior, suggesting a long decay from faith to predation.

His attempt to enthrall Kelly and savor the chase frames him as a sadist who enjoys domination for its own sake, which makes his beheading by Asil feel less like a victory lap and more like necessary sanitation.

Nura

Nura arrives as an emissary of tiger shapeshifter power, and she carries herself like someone used to being obeyed. She balances gratitude with authority—recognizing Asil’s effort to contact them, but also demanding the collar’s destruction because she understands how deep the threat runs.

Her method of calming Zoya in tiger form shows leadership rooted in instinct and family dominance, not cruelty. Nura’s presence widens the world beyond werewolves and vampires into a broader shapeshifter polity, hinting at court politics and ancient obligations.

Hamza

Hamza, Nura’s younger brother, is the heart-on-sleeve counterpart to her composure. His immediate horror at seeing Zoya caged reveals a strong moral compass and a protective family loyalty.

While he defers to Nura’s judgment, he is the one who voices the political stakes of the missing advisor, showing that he is not naïve—just more openly emotional. Hamza represents the next generation of tiger leadership: passionate, watchful, and already learning the cost of supernatural power games.

Zoya

Zoya is largely silent, but her fear and wariness carry the trauma of abduction and enchantment. Her family’s loss of tiger form for generations makes her situation feel like a cultural and biological wound, not just a kidnapping.

She reacts to dominance and safety through Nura, and her continued distrust of Asil even after rescue shows that healing is not immediate. Zoya functions as both a victim needing protection and a clue to a larger conspiracy targeting shapeshifters.

Bran Cornick

Bran Cornick, the Marrok, enters like a king stepping onto a battlefield after the swords have quieted. His authority is effortless; Asil respects him, but not submissively, which tells you how high both men rank in their own ways.

Bran’s quick read that “wider supernatural powers” are moving shows his strategic mind and long experience shepherding a volatile world. He accepts the collared tiger as a “Christmas present” with wry practicality, treating information as the true gift.

Bran anchors the larger series-level stakes: this isn’t just dating chaos, it’s a chessboard of predators and politics.

Tami Reed

Tami Reed is the story’s most painful betrayal. Introduced as a compassionate Spokane social worker and gentle gardener, she initially appears grounded, kind, and nervous in an ordinary human way, which makes her later reveal as Mariposa’s weapon feel like a trap laid for the reader too.

Her double life is shaped by indoctrination: raised by a black witch who framed vengeance as love, Tami performs empathy convincingly because she knows how to mirror it. She isn’t a cackling villain; she is a zealot who believes murder is family loyalty.

Her use of Helen as a power source and her readiness to sacrifice her show the depth of her corruption. Tami’s death—sudden, human, and at Joshua’s hand—highlights the tragedy of what she might have been without Mariposa’s shadow.

Joshua

Joshua is a teenage survivor with a spine of steel. He calls for help because he protects his little sisters, and he keeps his head in a supernatural crisis with the kind of street-smart practicality that saves lives.

His willingness to believe in wyrms and witches comes from experience with the world’s uglier corners. Most striking is his decisiveness: when Tami reveals herself and raises a knife over his mother, he acts without hesitation, ending the threat in a single shot.

Joshua embodies a raw, human heroism that doesn’t wait for permission.

Helen

Helen, Joshua’s mother, is a figure of devastation shaped by magical enthrallment and human collapse. Her hoarding isn’t just a personal failing; it is manipulated by a wyrm’s treasure-compulsion, turning her into both victim and danger.

She appears in trance, accusing others of theft, which shows how magic can hijack human pain into monstrous behavior. Her survival after the fire and the wyrm’s death leaves her future uncertain but suggests a fragile possibility of recovery once the supernatural hook is removed.

Mariposa

Mariposa never walks into the scene, but her fingerprints are everywhere. Asil’s foster daughter and black witch, she is the architect of his grief, having murdered his mate, and her legacy turns love into a weapon.

The amulet that twists Tami’s magic reveals Mariposa as a master of long games, shaping proxies to carry out vengeance years later. She represents the story’s theme of corrupted family ties: intimacy used to enslave, nurture used to poison.

Ruby

Ruby is a half-fae woman whose life has been a slow, controlled bleeding under Ivory Jim’s ownership. Her outward toughness and sarcasm are armor built over a century of captivity and fear.

She doubts her worth and dreads hurting others, which makes her agreement to involve Asil feel like both desperation and a bid for agency. Ruby’s supernatural sensitivity, her ability to read impressions from spirits, and her hidden age underscore that she is far more formidable than her binding allows her to be.

Her geas is heartbreaking: a forced isolation from the very kinds of power that could help her, designed to keep her prey. When she kills Ivory Jim, the burst of knives and watery darkness reads as both liberation and the return of a self she has had to bury.

Ruby grows into someone who can ask for a second date, heal Asil with her power, and stand as a host and ally in the final vampire siege. She is the emotional counterweight to Asil’s solitude: scarred, stubborn, and finally free enough to choose him.

Alan Choo

Alan Choo is a submissive werewolf whose loyalty is the spine of Ruby’s survival. He arranges the date as a calculated risk, not romantic meddling, because he understands Asil’s capacity to protect.

Alan’s terror upon realizing who Asil is shows the scale of Asil’s reputation, but his fear never turns into abandonment. He tries to cancel the date for Ruby’s safety, then pivots into support once events force honesty.

Alan is the quiet kind of brave: the person who keeps the machinery running, protects friends, and knows when to step aside so the truth can be spoken.

Terry

Terry, the team’s engineer, is a grounded professional presence inside the haunted-house chaos. He helps frame the ghost-hunting group as serious, not theatrical, and his inclusion emphasizes that Ruby’s circle is built from practical skills as well as supernatural sensitivity.

He functions as part of the social normalcy that Asil steps into, a reminder that everyday competence still matters in a world with monsters.

Max

Max is jovial, socially connective, and lightly touched by fae blood. His faint supernatural heritage makes him a bridge between Ruby’s hidden world and the human one, and his warmth helps normalize Asil’s presence to the group.

Max shows how mixed-blood individuals can exist in these stories not as tragic outcasts but as friendly, functional people woven into community.

Peg

Peg is shy but perceptive, and she becomes one of the earliest to recognize that magic is erupting when Ivory Jim attacks. Her alertness in crisis suggests that behind her quietness is sharp situational awareness.

Peg’s role is less about plot action and more about showing the team’s cohesion: they aren’t helpless spectators, they’re attentive allies who trust Ruby.

Dusty

Dusty, Peg’s dead twin brother, is a mischievous spirit and an unexpectedly vital participant. His ability to warn Ruby about Asil questioning Alan reveals agency beyond death, and his tripping of Ivory Jim during the battle makes him a literal force in the fight.

Dusty adds levity to the haunted house sequences, but he also shows what Ruby protects: a home where even the dead are treated as family.

Ivory Jim

Ivory Jim is the story’s embodiment of predatory fae ownership. He brands Ruby with blood magic, feeds on her in body and spirit, and keeps her isolated through a binding that weaponizes her own caution.

His starvation and corruption make him less refined trickster and more addict predator, driven by entitlement and hunger. He saunters into the house expecting obedience, and the casualness of that cruelty is what makes him terrifying.

His death at Ruby’s hands completes her arc from property to person, and his corpse being rolled away like garbage is a fitting reduction of his false grandeur.

Mari-Brigid Alvarez

Mari-Brigid is a trapped human navigating a gilded cage with sharp survival instincts. She is honest with Asil immediately, refusing the sexual expectation her husband forces on her, which shows a core of integrity that has survived years of abuse.

Her story reveals a life arranged by patriarchal and supernatural power—married off young, isolated, and used as bait for Alvarez’s games. Yet she is not passive; she works with Bobby to craft believable lies, seeks help when she senses a real ally, and plays her role at the ball with poised courage.

Mari-Brigid is a study in pragmatic resistance: she survives by strategizing, then chooses freedom when a door finally opens.

Bobby Anderson

Bobby Anderson is loyalty under duress. Trained, armed, and initially threatening to Asil, he is not a villain but a guard dog raised in someone else’s yard.

His family’s multigenerational servitude to Alvarez makes him another kind of captive. He protects Mari-Brigid not because he is ordered to, but because he has a conscience that refuses to die.

His blunt honesty about vampire politics and Alvarez’s function as Bonarata’s broker makes him a valuable witness. Bobby’s bond to Alvarez is psychological as well as supernatural, and his relief when it snaps speaks to how long he has lived half-owned.

Alvarez

Alvarez is the hidden master vampire, and the narrative treats him like a disease wearing silk gloves. His cruelty is systematic: sending his wife on dates, demanding explicit reports, and murdering men based on those stories is sadism turned into ritual.

The fact that neither Mari-Brigid nor Bobby has seen him directly adds to his mythic terror; he rules through distance and ancient minions. As the White Angel, he is revealed as an elder turned in childhood, giving him a chilling mix of innocence of appearance and monstrousness of appetite.

His plan to force Bobby into killing Mari-Brigid shows his love of cascading control. Alvarez is not just a personal abuser; he is a political node for Bonarata’s expansion, a parasite that feeds on both bodies and power structures.

His end beneath the lioness’s crushing intervention feels like a god striking down a tyrant.

Bonarata

Bonarata exists mostly as looming geopolitical pressure in vampire society. He is portrayed as a powerful lord moving his base toward the United States, with Alvarez as a key broker of borders and influence over humans and fae.

Even without direct appearance, Bonarata’s shadow expands the story from local horror to continental power shifts, hinting that Asil’s battles are part of a much larger war.

Angus

Angus, Seattle’s Alpha, is a quick, reliable commander who responds to Asil’s warning without ego. His readiness to prepare an ambush and his pack’s effectiveness against elder vampires show why territorial Alphas matter: they are the frontline governance of supernatural cities.

Angus represents competent leadership that trusts Asil’s judgment while holding the city together.

Moira

Moira, the witch allied with the Emerald City werewolves, is a stabilizing force in the mansion defense. She participates in killing elder vampires and ensuring their remains cannot regenerate, which demonstrates practical magical expertise rather than flashy spellcraft.

Moira symbolizes the necessary alliance between witches and werewolves when vampire politics become war.

Sherwood Post

Sherwood Post appears briefly at the end, but his presence is a quiet thematic closure. As the Marrok’s older brother and a man Asil sends on a date with Kelly, Sherwood becomes part of Asil’s gift economy—repaying Kelly’s decency by giving him a safe, meaningful connection.

Sherwood’s calm role in the epilogue suggests a future shaped by healing, community, and choice rather than coercion.

Themes

Solitude, companionship, and chosen connection

Asil begins Blind Date with a Werewolf in a place of self-contained isolation that feels older than simple introversion. His pack reads his distance as stagnation, not safety, and the prank of enforced dates is their clumsy way of pushing him back toward the messy world of people.

What makes this theme work is that solitude is not treated as a quirk to be fixed. It is presented as a survival habit for someone who has lived long enough to associate closeness with loss and danger.

Asil agrees to the challenge partly out of amusement, but also because the pack’s meddling gives him permission to try connection without admitting he wants it. Each date becomes a different mirror for what companionship could look like.

With Kelly Lieberman, a total stranger who refuses to be intimidated, Asil experiences company stripped of old history. Their night starts as an accident and a joke, yet it shifts into a real partnership the moment they choose to continue together.

Kelly’s decency and humor cut through Asil’s expectations that proximity only leads to pain. With Tami, companionship is shown in a darker form: the appearance of warmth can be weaponized, and a friendly setting can hide a trap.

That contrast sharpens the idea that connection is both a risk and a need. Ruby offers the most complex version of companionship because she is not simply a date; she is someone whose very survival depends on trust.

Their bond grows from shared danger rather than romantic intent, and the story treats the slow movement toward warmth as a kind of healing. By the end, Asil is still the same ancient wolf, but he is no longer defined solely by distance.

The pack’s “Concerned Friends” wager on failure, yet what they unintentionally do is place him in situations where he can practice being with others again. Companionship here is not framed as a cure for loneliness; it is framed as a decision made again and again, even when history makes that decision hard.

Agency, consent, and the fight against control

Power over one’s own life is a constant pressure point in Blind Date with a Werewolf, and nearly every major conflict turns on who gets to choose. The dates themselves begin as a theft of agency: Asil’s pack creates a profile for him, schedules meetings, and treats his personal boundaries as group entertainment.

He accepts their game, but the story never pretends this is a harmless prank. It is a reminder that even within family structures, consent can be ignored when people believe they know what is best for someone else.

That same problem escalates into far more violent forms when supernatural predators enter the picture. Vampires mesmerize, collar magic enslaves, geases bind, and fae tattoos track and drain.

These are not just fantasy devices; they are literalizations of coercion. Kelly’s brush with a vampire bite he didn’t understand shows how control can be placed on a person without their knowledge.

Zoya’s kidnapping and collaring show agency erased by force and ritual, and the fact that her family has lost tiger form for generations adds another layer: vulnerability increases when identity is already compromised. Ruby’s wrist tattoo is the sharpest example.

Ivory Jim’s ownership is not metaphorical; it is written into her body, her magic, and her ability to seek help. The theme becomes even more pointed when the geas prevents her from approaching powerful allies, meaning her agency is attacked not only by violence but by isolation.

Mari-Brigid and Bobby live under another version of control—social, financial, and supernatural. Alvarez’s system of sending her on dates, demanding reports, and murdering men as punishment converts intimacy into surveillance and terror.

What stands out is how the story treats liberation. It rarely comes from a single heroic act; it comes from moments where people reclaim choice under impossible pressure.

Kelly refuses the vampire’s command. Joshua pulls the trigger to stop Tami.

Ruby speaks Ivory Jim’s true name and then, when her binding breaks, decides her own attack. Mari-Brigid gives Asil the truth even though she has been trained to lie for survival.

Asil’s role is complicated—he protects others, but he also sometimes decides for them. The narrative is aware of that tension.

It suggests that real safety isn’t just being saved; it’s being able to act, to say no, and to be believed when you do.

The ethics of violence and the burden of protection

Violence in Blind Date with a Werewolf is never decorative; it is moral terrain. Asil is introduced as a legendary killer, and the pack’s betting pool assumes destruction will follow him like weather.

Yet the story keeps asking what violence is for, who it protects, and what it costs. Asil’s fights are often brutal, but they come attached to responsibility rather than appetite.

When he kills Bruce the vampire, it is not a victory lap; it is an urgent act to prevent a human from being enslaved. The scene is staged so that Kelly’s survival depends on Asil’s speed and skill, but it also forces Asil to confront his own instincts.

His wolf wants to take over, and his discipline in public spaces shows that power without restraint is indistinguishable from threat. The second date aftermath in the barn pushes this further.

Asil frees captive big cats, but the humans die not by his hand, rather by the tigress exacting her own justice. The story is careful about this distinction: Asil refuses to be an executioner by convenience, yet he recognizes that releasing a wronged predator may lead to blood.

His choice is still an ethical one, even if the consequences are messy. With Tami’s betrayal, violence becomes tragic necessity.

Joshua’s killing of Tami is not written as cathartic; it is a teenager forced into adulthood by a trap laid for him and his sisters. The wyrm consuming Tami’s body and Asil burning the hoard house to erase evidence underline how violence can clean up a threat while leaving survivors with silence and scars.

The final arc against Alvarez is the most explicit statement of this theme. Alvarez’s cruelty is systemic and long-standing, entangling Mari-Brigid, Bobby, and wider political danger.

Asil decides he must die, not out of revenge but because leaving him alive guarantees more victims and strengthens Bonarata’s expanding power. Still, Asil pays for that choice with wounds, exhaustion, and the risk of becoming bonded to the very monster he hunts.

Even the lioness’s intervention, crushing Alvarez when Asil is pinned and bleeding out, carries a moral weight: she breaks her promise to stay back because allowing him to live would be another kind of violence. Protection here is not gentle; it is a job that sometimes requires killing, and the ones who do it carry the memory of each death.

The book doesn’t romanticize that burden, but it does respect it.

Identity, transformation, and living with multiple selves

Supernatural identity in Blind Date with a Werewolf is more than flavor; it is a daily negotiation of self. Asil’s age, religion, and werewolf dominance create layers that do not always fit neatly together.

He is called “the Moor,” a label that compresses history into stereotype, and he carries a Muslim identity in a pack culture that treats Christmas as a communal marker. His quiet correction—Christmas means little to him—signals that identity is not just species or power rank.

It includes faith, culture, and the memories that come with them. The theme continues through characters whose forms are unstable or suppressed.

Zoya belongs to a tiger line that has lost shape-shifting ability for generations, so her very body is a record of family trauma. When Nura enters the cage as a tiger to calm her, it is both rescue and cultural restoration, reminding Zoya of a self she has been cut off from.

Ruby’s half-fae nature and bound magic show another kind of split identity. She is powerful and ancient, yet forced to present herself as ordinary and weak to survive the geas.

Her friends perceive her as a fragile leader; Asil smells the older truth underneath. The moment her power erupts against Ivory Jim is not just a fight scene.

It is identity reclaiming space after decades of suppression. Mari-Brigid is human in biology but treated as livestock in a vampire marriage.

Her identity has been rewritten by fear and performance, until Asil’s presence allows the truthful version of herself to re-emerge. Even Kelly’s night at the masquerade ball highlights the thin line between play-acting and real nature.

LARPing and costumes blur into an encounter with an actual vampire, showing how easily a person can be participating in a story bigger than they realize. For Asil himself, transformation has two meanings: the physical shift into wolf, and the internal shift between lethal instinct and controlled protector.

The narrative treats these selves as coexisting, not as one “true” self and one shameful shadow. His wolf speaks again only after he survives the final battle and returns to Ruby, suggesting that accepting connection helps integrate his fractured inner life.

Identity here is not a static label; it is what survives captivity, what adapts under threat, and what gets rebuilt through mutual recognition.

Community, loyalty, and imperfect care

The pack’s meddling begins the plot, and in doing so it exposes how community care can be both loving and invasive in Blind Date with a Werewolf. The “Concerned Friends” act out of real worry.

They want Asil engaged, laughing, present. But their method turns him into entertainment, and their betting pool shows how affection can carry cruelty when people stop taking another person’s boundaries seriously.

That tension is the heart of the community theme: belonging offers safety, yet it can also pressure individuals into roles they didn’t choose. Still, the story keeps returning to the idea that none of these characters survive alone.

Kelly’s willingness to stay after realizing the setup was a prank is a small act of loyalty to a stranger, but it becomes crucial because it leads him into partnership against the vampire. Meg’s panic and her attempt to yank Kelly away show another kind of loyalty—protective, anxious, sometimes controlling.

Nura and Hamza arriving for Zoya reinforce family obligation that crosses continents; they treat retrieving her not as optional kindness but as duty. Bran Cornick’s arrival at the barn, and Asil handing over a captive tiger as a “present,” show a political form of loyalty: alphas and elders sharing threats and burdens because the health of the wider supernatural world depends on it.

Ruby’s ghost-hunting crew is a different model of community. They are not powerful, and some are half-fae or human, but they have built an interdependent household where a dead twin brother’s spirit is treated as family rather than horror.

When Ivory Jim attacks, that community does not flee; they hold the line while Ruby and Asil fight. Mari-Brigid and Bobby also represent loyalty forged under oppression.

Bobby’s family has served Alvarez for generations, and his loyalty is coerced, yet he still tries to protect Mari-Brigid from the worst of Alvarez’s expectations. Their trust in Asil at the ball is risky, but it shows how alliances form when people choose each other over fear.

By the closing scenes, Asil arranging a date for Kelly with Sherwood Post is his answer to the pack’s earlier manipulation: he uses community influence to give someone a possibility, not to trap them. The book argues that care isn’t proven by control; it’s proven by standing beside someone when danger is real, and by learning to respect their choices even when you think you know better.