Bonds of Hercules Summary, Characters and Themes

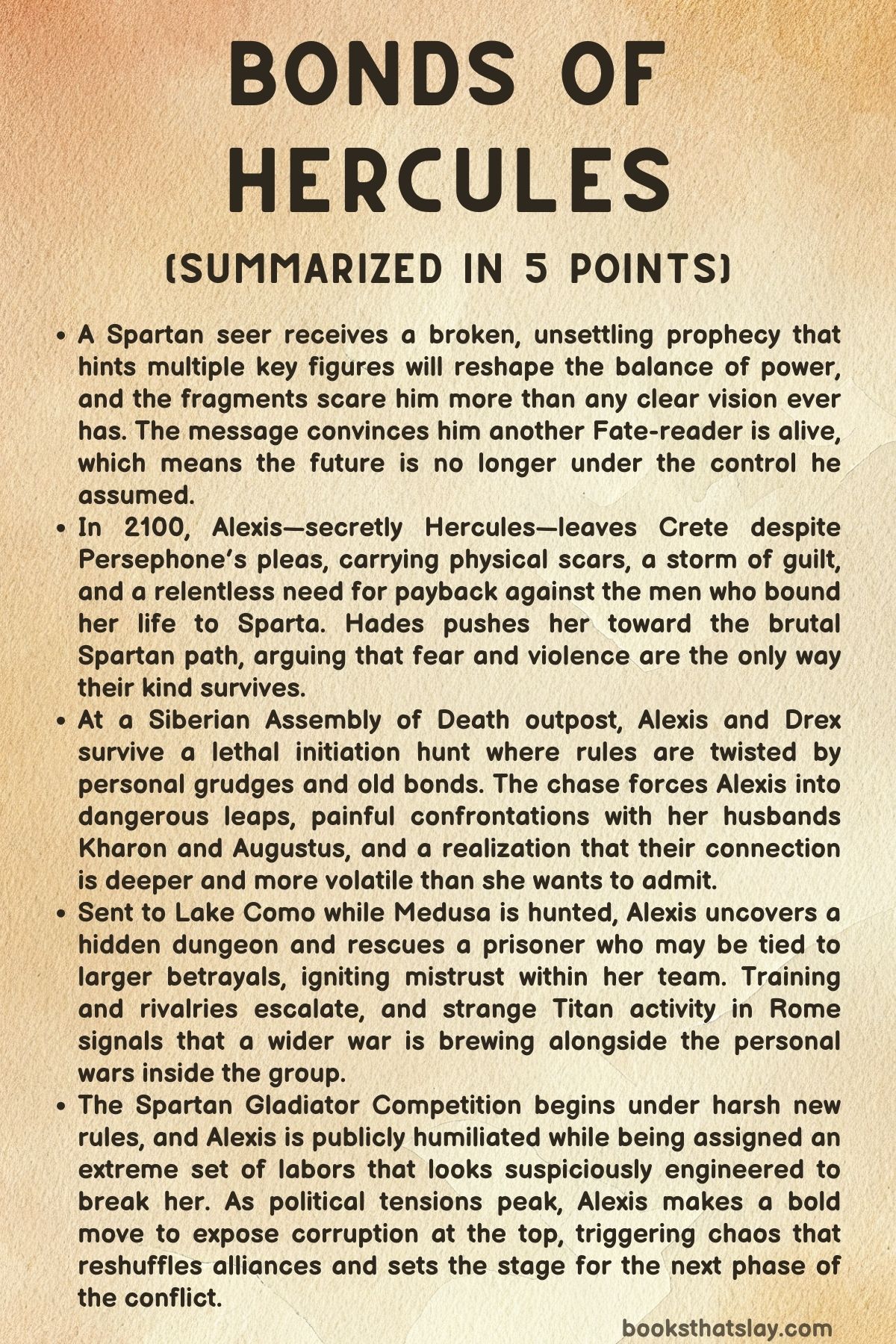

Bonds of Hercules by Jasmine Mas is a mythic-futurist dark romance set in a brutal Spartan world ruled by Olympian politics and chthonic assassins. The heroine, Alexis—secretly the reincarnated Hercules—carries physical scars, a violent power in her blood, and the haunting voices of those she’s killed.

Fleeing a forced marriage to two deadly husbands, she is pulled back into Sparta’s gladiator culture just as Fate itself begins to fracture. Prophecy, betrayal, and shifting loyalties collide while Alexis fights to survive, protect those she loves, and expose the rot at the heart of divine rule.

Summary

An elderly Spartan seer smokes a pipe to enter trance and read Fate, but the prophecy arrives shattered. He hears fragments about a “lost one” who will change what exists, a figure tied to death’s soldiers who will become more, and names like Kharon and the Serpent of Lore.

A “chained one” will reveal hidden evil, and a “monstrous one” will mend what’s broken. The seer is rattled: prophecies never come this unclear unless another Fate-reader lives.

Someone else with the rare Spartan gift is out there, and that means the balance of power is about to tilt.

In May 2100 on Crete, Alexis—whose true name is Hercules—stands outside the palace of the House of Hades. She remembers Persephone once asking Hades if human deaths during a mission were avoidable, only for him to return covered in blood and refuse to explain.

The memory adds to Alexis’s spiraling guilt. She has a blind left eye, a damaged left ear from childhood abuse, and a constant inner chorus of dying voices from people she has killed.

Persephone begs her to stay on Crete, promising safety from the Spartan Federation and the Assembly of Death. Persephone’s bond with Hades has expanded her ability to sense every living thing on the island, making lies impossible and letting her feel Alexis’s fear and rage through the land itself.

Alexis wants peace for herself and Charlie, Persephone’s quiet companion, but she believes she was made for war. She intends to return to Sparta, reclaim her poisonous power, and punish the husbands who trapped her.

Persephone warns the path will cost her soul. Alexis answers that the world never offered her kindness anyway.

Hades waits with Cerberus and tells Alexis Spartans like them are born for battle. In Sparta, survival requires becoming terrifying.

He insists the Assembly’s hunt is hazing and that she should make them fear her. When Alexis repeats his maxim—“No one fears the sane”—Hades takes her hand and uses Domus to leap them into Hell.

They reappear at a black outpost in Siberia, where Chthonic assassins line up for initiation. Two of them are Kharon and Augustus, Alexis’s husbands, who stare at her with hungry hostility.

Mentors Achilles and Patro are there with their beasts, along with Hermos and Agatha. Artemis rides in on a monstrous black horse and announces two new recruits: Alexis and Drex, an exiled Olympian heir trying to redeem his disgraced mentor’s legacy.

The initiation is a twenty-five-mile hunt through the forest. Recruits get an hour head start; they cannot leap or fight back.

If caught, they die. If they last until morning, they join and may choose mission partners.

Artemis shouts for them to run.

Alexis and Drex sprint into the icy woods. From Kharon’s view, the hunt is personal.

The marriage bond that forced Alexis to them has magnified their power and pain. His rage spikes when Hermos shoots Drex in the arm and Alexis in the calf.

Alexis refuses to leave Drex behind, dragging him while bleeding. Kharon, furious that his wife was harmed, executes Hermos on the spot and resumes the chase.

In a clearing, Augustus and Patro try to lure Alexis away from her husbands. Achilles blocks violence between the men.

Despite her injuries, Alexis leaps, rematerializing beside Kharon at the tree line. She grabs him and leaps again, dragging him to a Montana field near a militarized protected zone.

Kharon ties a tourniquet and tries to help her, but Alexis explodes with accusations—betrayal, stalking, kidnapping, and murdering any man who touched her. Kharon insists the marriage was meant to protect Chthonics from oppression and says he is trying to be better.

Alexis calls the relationship “just physical,” and Kharon snaps. She shoots at him and misses; he critiques her stance coldly.

She tasers him instead. He doesn’t fall.

He walks through the electricity, blood sizzling, grabs her chin, and kisses her while sparks leap between them. Augustus arrives, sees them, and orders Kharon to kiss her again.

He obeys. When Alexis repeats “just physical,” Kharon recoils as if struck.

Augustus decides to leap all three back, but Alexis refuses and leaps alone. The jump goes wrong because of her wounds.

She crashes into a humid rock tunnel lit by torches, hearing a woman scream ahead. Nyx, her inner guide, urges her to flee, but Alexis chooses the dark passage toward the screams.

Back at the outpost, Augustus overhears Hades telling Ares that Alexis was found unconscious in a dungeon alcove under the Cretan palace after a mis-leap; she barely avoided coma. Augustus, suffering migraines and bleeding eyes from the bond punishment, tries to see her, but Hades blocks him and condemns him as a disgrace.

Sirens then blare: Medusa has escaped the Underworld and killed two Olympians. Debate erupts, especially when Agatha reveals her Gorgon nature.

Augustus explains Medusa is feared not just for bloodline but for Fate power, and Kharon goes silent—Medusa is his sister. Artemis arrives with a battered Alexis and orders her to pick mission partners.

She chooses Achilles and Patro, not her husbands, and everyone is sent to Augustus’s Lake Como villa until Medusa is captured.

At the villa, Alexis returns to the place of her forced wedding. Augustus brings Charlie, claiming Persephone approved his joining tutoring with Helen.

Alexis, Drex, Helen, and Charlie sleep together for safety. That night Alexis hears screams again and discovers a hidden dungeon beneath the villa.

There she finds Ceres, a pink-haired muse, chained and tortured by Augustus. Despite warnings from Nyx, Alexis frees her.

Augustus and Kharon catch them, but Helen argues they can keep Ceres guarded while they investigate. Patro wants to interrogate Ceres by touch, but Alexis refuses to retraumatize her.

Under strict limits, Patro touches her and asks if she helped Theros. She says no, and Patro admits she isn’t lying, though he remains suspicious.

Ceres remembers almost nothing except the name “Zeus,” terrifying the girls.

Training begins in an underground course where older Chthonics hunt Alexis and Drex through darkness and explosions. Alexis can’t hit anyone.

Kharon corners her, forces her to hear his obsessive thoughts, and taunts that it isn’t only physical. Afterward her husbands pressure her in the showers, and she yells that she understands, overwhelmed by the tug-of-war for control.

On mission day, Persephone visits Alexis secretly, hinting that Alexis’s mixed Hades-Demeter bloodline is far more dangerous than anyone realizes. Artemis divides teams: Alexis goes to Rome with Patro and Achilles while others go to Canada and the Amazon.

Titans are behaving oddly, and Medusa’s escape is accelerating war. Each hunter must return with a Titan lip-tag.

In Rome, the city feels wrong—too silent for a Titan in a protected zone. Patro dismisses her unease.

Near the Colosseum, he stops her and says he and Achilles have waited to be alone with her.

Soon after, the Olympian rulers move the Spartan Gladiator Competition up. Competitors, including Alexis, are chained in cells beneath the coliseum.

Even Charlie and Helen are confined, enraging Alexis and Augustus. In a tiny cell with only one bed, tension flares; Kharon and Augustus kiss Alexis, but Augustus pulls back, insisting on rest.

Alexis’s protector beast, Fluffy Jr., collapses and convulses. Augustus fears a tumor but notes a rare alternative: molting.

Alexis clings to the belief he is molting and will live.

Opening ceremonies bring them into a roaring arena. Zeus announces thirteen days of blade-only combat.

Dice decide the number of opponents and rounds. When Alexis—competing as Hercules—steps forward, Ajax rips her toga to humiliate her.

Zeus assigns her the worst fate: twelve labors over three rounds. Kharon snaps Ajax’s neck for dishonoring her.

Hades and Persephone demand a re-roll, but Zeus refuses. Alexis hides her suspicion that the dice were rigged.

At a packed symposium, Athena confronts Alexis for the mounting chaos. Alexis reveals she secretly recorded an interrogation with Zeus and broadcasts it to everyone.

On the recording, she accuses Zeus of orchestrating the Titan assault, framing Medusa, and arranging her attempted murder. She pulls down her toga to show a scar from the plan.

Zeus, cornered, admits it all and mocks her. The hall erupts; Chthonic and Olympian leaders react with fury while Zeus vanishes in smoke.

Fate declares his betrayal public, naming the prophecy fulfilled.

In the panic, Alexis sees Patro and Achilles crack away toward Helen’s room. She races back to the villa with her husbands.

They find the room wrecked and Patro pinning “Ceres” to the wall. He rips off her wig, revealing Medusa.

Patro rages that Alexis freed a traitor. Kharon and Augustus shield her, and Alexis shouts that Zeus himself admitted Medusa was framed.

Alexis then explains the truth. During her mis-leap from Montana, she landed in the Underworld prison and followed screams to Medusa strapped under an age-stasis device while Hermes guards taunted her.

Alexis and Nyx killed the guards, freed Medusa, and carried her out. Hades warned Medusa was federation property but ultimately honored Alexis’s choice and helped them escape.

Needing a decoy, Alexis later returned to the villa dungeon, forced the real Ceres to confess to aiding Theros in murdering children, then killed her with her poisonous blood power. Helen chose to help cover it up.

They disguised Medusa as Ceres, staged a breakout, and Persephone disposed of Ceres’s body on Crete.

Two weeks later, Athena—now interim speaker—pardons Medusa but orders her to enroll at Rhodes Olympian University to study Fate. For safety, she must have two full-time bodyguards.

Hades assigns Patro and Achilles, the feared Crimson Duo. Medusa insists Alexis attend too, and Athena allows it.

Back at the villa, Alexis finally opens up about her foster-parent abuse and killing her foster mother to protect Charlie. Her husbands reveal they have captured her foster father and offer her vengeance.

Alexis stabs him with the Rod of Asclepius and walks away without regret.

The story closes with Patro’s darkening fixation on Medusa and Fate’s unseen forecast: a “lost one” will remake Sparta, Medusa will be bound to the Crimson Duo, and her powers will help heal allies and reshape the coming war.

Characters

Alexis (Hercules)

Alexis, whose true name is Hercules, is the emotional and moral center of Bonds of Hercules. She is a Spartan forged by abuse and war, carrying visible scars—blindness in one eye, partial deafness, and a body battered by childhood violence—and invisible ones, like the chorus of dying voices she hears from those she has killed.

Her inner life is a constant collision of rage, guilt, and a desperate craving for autonomy. Even when offered safety on Crete, she chooses the harsher path back to Sparta because ease feels like betrayal of who she has become.

Alexis’s agency is hard-won; she refuses to be reduced to a pawn, a wife, or a weapon, even as the world keeps trying to make her one. This stubborn will is both her salvation and her danger: she repeatedly risks herself for others—dragging Drex while wounded, freeing a prisoner in the dungeon, exposing Zeus publicly—yet she also embraces vengeance with chilling clarity when given the chance.

Her arc moves from survival and refusal to break, toward becoming a disruptive force in fate and politics, a “lost one” whose decisions reshape the balance of power.

Kharon

Kharon is one of Alexis’s husbands and embodies possessive devotion sharpened into violence. His love is not gentle; it is obsessive, territorial, and fused to a Spartan belief that protection equals control.

The forced marriage bond intensifies his power and pain, leaving him unstable and furious when Alexis escapes. Yet beneath that volatility sits a warped kind of conscience—he kills Hermos not because it breaks rules but because Alexis was harmed, showing his personal loyalty outweighs institutional law.

Kharon oscillates between predator and guardian: he stalks, kidnaps, and mutilates in her name, then strips off armor, binds her wound, and looks genuinely horrified by her self-destruction. His conflict is not about whether he loves her, but what that love permits him to do.

The story keeps pressing him toward a reckoning: if he claims he married her to protect Chthonics, he must confront the possibility that he is also one of her cages. His silence around Medusa’s escape reveals another layer—family loyalty and grief—hinting that his ferocity has roots in loss as much as desire.

Augustus

Augustus is Alexis’s other husband and functions as a colder mirror to Kharon’s heat. He is controlled, strategic, and politically aware, a man who believes survival depends on containment—of enemies, information, and even emotions.

The marriage bond punishes him physically with migraines and bleeding eyes, suggesting power for him is always paired with cost, and control is partly a defense against unraveling. His cruelty surfaces most starkly in the villa dungeon where he tortures Ceres, showing how far he will go to protect what he sees as the greater good.

Yet Bonds of Hercules complicates him by giving him real tenderness toward Alexis’s safety: he orders perimeter defenses, gives her a pager, insists she leap away if needed, and stops sexual escalation when rest and readiness matter. He wants her alive more than he wants to win her affection.

His tragedy is that the same protectiveness that could redeem him also fuels violations of her trust; he cannot fully grasp that fear and coercion, even when rationalized, are still forms of harm. Augustus stands at the fault line between devotion and tyranny, and the narrative keeps asking whether he can cross it without losing her—or himself.

Persephone

Persephone is the rare figure who offers Alexis love without ownership. Her power is rooted in land and life, and on Crete that power enlarges into near-omniscience; she senses every living thing and every deceit, making her both sanctuary and witness.

Emotionally, Persephone is a fierce protector who understands Alexis’s trauma as something felt in the soil, not just spoken aloud. She begs Alexis to stay not from weakness but from clarity: she sees that Sparta’s path will erode what remains of Alexis’s soul.

Persephone also carries political courage, quietly hiding Medusa and helping set a decoy plan in motion, even knowing it pits her against Olympian authority. She represents an alternative model of strength—nurturing, intuitive, and rooted in connection rather than domination.

Her role in the prophecy thread suggests she is not merely a comfort figure; she is an amplifier of change, someone whose love and power help catalyze Alexis into becoming more than a weapon.

Hades

Hades is a mentor-guardian figure whose worldview is carved from war. He believes Spartans like Alexis are made restless by nature, that sanity is weakness and fear is currency.

This philosophy can read as brutal indoctrination, but in Bonds of Hercules it also functions as a bitter kind of honesty about the Spartan system. Hades does not pretend the world is fair; he teaches Alexis to survive it by becoming legend.

His loyalty to her is visceral—he is furious at Zeus’s manipulations, protective when she is injured, and ultimately honors her choice to free Medusa despite the political fallout. That moment is important: for all his hardness, Hades respects agency.

He is also tied to the broader stakes of fate and war, reacting not just as a father-figure but as a ruler who recognizes that Zeus’s betrayal could fracture worlds. Hades stands for the old order of Spartan power, but his backing of Alexis hints he may be willing to let that order be remade.

Charlie

Charlie is quiet but pivotal, serving as Alexis’s anchor to humanity. His presence is tied directly to her origin trauma—she killed her foster mother to protect him—and that protective instinct still governs her choices.

Charlie’s silence is not emptiness; it’s survival intelligence. He reads danger, signals Persephone’s lies subtly, and moves carefully within a world of monsters and gods.

He represents what Alexis is trying to preserve inside herself: innocence, loyalty without violence, and love that doesn’t demand blood. The narrative keeps him close whenever Alexis teeters toward moral freefall, making him the living reminder that her fight is not only for vengeance but for a future where he can be safe.

Nyx

Nyx is the inner voice of caution, fear, and sometimes ruthless pragmatism inside Alexis. She is not just a conscience; she is a survival mechanism shaped by trauma, constantly urging flight, restraint, or self-preservation.

Alexis repeatedly defies her—choosing the screaming corridor, freeing Ceres, staying in Rome despite dread—showing that Nyx’s role is to embody the pull toward safety while Alexis embodies the pull toward meaning. Their relationship externalizes Alexis’s psychological battle: Nyx is the part that wants to live, Alexis is the part that wants to live for something.

As the stakes rise, Nyx becomes a measure of how far Alexis is drifting from fear into fate-shaping resolve.

Artemis

Artemis is authority made terrifying. She enters scenes like a storm—mounted on a monstrous horse, radiating dread—and her role as recruiter and judge for the Assembly of Death positions her as both gatekeeper and executioner.

She enforces Spartan tradition with cold ceremonial violence, slaughtering Cyclopes in a display that reminds everyone who holds power. Artemis is less a nurturer of soldiers than a sculptor of weapons; her initiation hunt is designed to break recruits or reveal what they are.

Yet she is not chaos for chaos’s sake. Her actions reflect a strategic awareness of the wider war with Titans and the political fragility caused by Medusa’s escape.

Artemis represents the uncompromising Spartan machine, and her approval is both a prize and a threat hanging over the younger Chthonics.

Patro

Patro is a volatile blend of brilliance, trauma, and possessive hunger. As a mentor and member of the feared Crimson Duo, he is lethally competent, but emotionally he is raw, jealous, and easily destabilized by threats to his control over Alexis or Achilles.

His contempt for Gorgons and his explosive reaction to Medusa reveal ingrained prejudice tied to fear of Fate’s power. Patro’s jealousy toward the husbands, and later toward Medusa, feels less like simple rivalry and more like a desperate attempt to secure belonging in a world where intimacy has repeatedly been weaponized against him.

The narrative exposes his tenderness only through Achilles, showing that love is possible for him but always tangled with dominance and fear of abandonment. His arc is slippery: he can be protective and loyal, yet also cruel, coercive, and dangerously fixated when his trauma is triggered.

Achilles

Achilles appears as Patro’s stabilizing counterpart—quietly fierce, deeply loyal, and emotionally clearer. He acts as a buffer between Patro and others, stepping in during conflicts and backing Alexis when Patro overreaches.

His protectiveness doesn’t carry the same overt need to control; instead it reads as devotion to both Patro and the people Patro claims as “theirs.” Achilles’s strength is in constancy: he loves Patro without flinching at his darkness, and that love becomes a source of power and peril. When he tells Patro that Alexis will be theirs, it shows he is not innocent of Spartan possessiveness; he is simply more composed in it.

Achilles embodies the frightening calm of a warrior who knows exactly what he wants and will not be swayed by guilt.

Drex

Drex is the underdog who refuses to stay small. As an exiled Olympian heir with a disgraced mentor, he enters the Assembly carrying shame he didn’t choose and a determination to prove he belongs.

His initiation alongside Alexis reveals grit and loyalty; even shot and bleeding, he keeps moving with her help, forming a bond built on shared survival rather than politics. Drex also functions as a rare peer for Alexis—someone outside her marriage and mentor entanglements—offering companionship that isn’t sexualized or hierarchical.

His arc suggests a coming transformation from nervous recruit to genuine force, potentially one of the “monstrous ones” or fate-touched figures the prophecy hints at.

Agatha

Agatha is a study in controlled monstrosity. Her revealed Gorgon visage and her defensive anger at Patro’s rant show that she has lived under suspicion and hatred long enough to sharpen her identity into armor.

She is not portrayed as soft or tragic; she is proud, dangerous, and unwilling to shrink for Spartan comfort. At the same time, she respects rules and hierarchy until they cross personal lines, which makes her a disciplined soldier rather than a rogue threat.

Agatha’s presence broadens the story’s theme that “monster” is a political label as much as a biological one.

Hermos

Hermos is the clearest example of Spartan cruelty without restraint. He shoots Drex and Alexis during the hunt not from necessity but from opportunistic aggression, treating the initiation as a chance to wound rivals.

His death at Kharon’s hands is framed less as tragedy and more as consequence, highlighting how the Spartan culture eats its own. Hermos’s role is short but important: he embodies the everyday violence Alexis is returning to, the kind that masquerades as tradition while serving personal sadism.

Medusa

Medusa is both symbol and person in Bonds of Hercules. Publicly she is mythic terror—an escaped Gorgon accused of killing Olympians—but privately she is a fate-touched prisoner whose suffering exposes Olympian hypocrisy.

Her power is not just petrification or bloodline; it is access to Fate itself, placing her at the heart of the prophecy and the war’s turning point. Medusa’s disguise as Ceres and her tense confrontations with Patro show a woman who has learned to survive through deception and fury, yet who also seeks allies, pushing for Alexis to join her at university.

She is traumatized but not broken, defiant even when cornered, and unwilling to accept the role of villain the world wrote for her. Her forced bond to the Crimson Duo sets up a fraught dynamic: she is chained to the very men who fear what she represents, and that tension is poised to become either healing or catastrophe.

Zeus

Zeus is the architect of betrayal and the face of corrupt power. He manipulates Titan attacks, frames Medusa, and tries to have Alexis killed, all while hiding behind law and spectacle.

His public confession at the symposium is chilling because he doesn’t crumble; he sneers. Zeus embodies leadership divorced from accountability, treating war and lives as chess pieces for supremacy.

His disappearance after exposure doesn’t end his danger, it deepens it, because it drives the political order into instability and leaves a vacuum that others may fill with equal ruthlessness. He is less a complex antagonist than a deliberate one: the story needs him as the rot that must be revealed for the world to change.

Athena

Athena serves as pragmatic order after Zeus’s collapse. She confronts Alexis not out of malice but to demand truth, and when truth detonates the room, she pivots into governance—pardoning Medusa while containing risk through mandated study and bodyguards.

Athena’s strength is institutional realism; she recognizes that justice and security must be balanced in a volatile federation. She is neither wholly ally nor adversary, but a leader trying to keep a fractured system from burning down.

Her decisions shape the new political terrain in which Alexis and Medusa will have to survive.

Ares

Ares operates in the background as a war-hardened authority aligned with Hades. His importance is in what he represents: the Spartan martial establishment that sees conflict as inevitable and readiness as sacred.

His presence in strategic conversations, like the investigation into Titan activity, positions him as a stabilizing war engine. He is less emotionally textured in the summary, but his role reinforces the sense that Sparta’s leaders are already braced for apocalypse.

Aphrodite

Aphrodite is a political alarm bell. She arrives with intelligence about Titan presence and redirects leaders into action, showing she is not simply a goddess of allure but a figure of influence and information within the Chthonic hierarchy.

Her unbeaten scar record and place among top leaders underline that her power is feared and respected. She embodies the idea that beauty and brutality coexist in Spartan divinity, and that war is as much about perception and momentum as blades.

Fate

Fate is the impersonal spine of the story. It appears through prophecy, labors, and public declaration, acting almost like a cosmic narrator that confirms when a turning point has arrived.

When Fate declares Zeus’s betrayal and the prophecy fulfilled, it’s not moral judgment so much as a statement of inevitability. Fate’s presence makes every character’s struggle feel simultaneously personal and prewritten, and the tension of the book lives in that gap: people fighting like their choices matter inside a universe that keeps insisting they are threads in a larger weave.

Ajax

Ajax is the enforcer of Spartan spectacle, using humiliation as a weapon. Ripping Alexis’s toga open in front of the arena reveals his function: to remind competitors that tradition excuses cruelty, especially toward those already targeted.

His death—Kharon snapping his neck—is a dramatic refusal of that tradition by someone who normally upholds Spartan law. Ajax is not just a villainous guard; he is a symbol of institutionalized degradation that Alexis’s presence begins to overturn.

Fluffy Jr.

Fluffy Jr., Alexis’s massive protector beast, is an extension of her vulnerability and hope. His convulsions and possible molting mirror Alexis’s own fear of losing what she loves and her refusal to accept easy despair.

She clings to the idea that he is transforming, not dying, because believing in his survival is tied to believing in her own possibility of renewal. Fluffy Jr. is also a quiet reminder that power in this world is not only human; bonds with beasts are emotional lifelines and strategic forces, and his growth may signal a coming escalation alongside Alexis’s own unfolding destiny.

Cerberus, Hydra, and Poco

These protector beasts function as emotional and thematic punctuation. Cerberus, beside Hades, reflects his dominion and watchfulness, reacting to Augustus in ways that amplify Augustus’s guilt and danger.

Hydra, small but fierce at Charlie’s side, symbolizes Persephone’s protective nurture and the fragile safety she tries to build for her people. Poco, Augustus’s raccoon protector, is almost tenderly ironic: a soft, clever creature guiding a hard, tormented man through pain, suggesting that even the most ruthless Spartans carry something small and loyal at their heels.

Themes

Fate, Prophecy, and the Limits of Foreknowledge

From the opening with the Spartan seer, the story positions Fate as both authority and puzzle. The prophecy arrives fragmented, which is abnormal in this world, and that abnormality matters more than the content itself.

Clarity has been a kind of social contract: prophecy gives direction, legitimizes power, and reduces uncertainty. When it breaks, the people who rely on it break too.

The seer’s terror at the possibility of another Fate-reader alive shows how knowledge of the future is also a monopoly. Whoever reads Fate can sway politics, warfare, and personal trajectories.

In Bonds of Hercules, prophecy is not a comforting roadmap; it is contested terrain. Names like Kharon, “the Serpent of Lore,” and “the monstrous one” function as half-lit signposts, forcing characters to act without full context.

That produces a world where choices must be made inside uncertainty, and therefore responsibility cannot be fully outsourced to destiny.

Medusa embodies this tension most sharply. She carries a rare power of Fate, and the entire federation’s fear of her is not only about what she might do, but about what she might know.

Her imprisonment under an age-stasis device is a political act aimed at freezing a future that threatens Olympian control. When Alexis frees Medusa, the act is framed less as rescuing a person and more as releasing a force that can rewrite the rules of prediction itself.

Later, Fate’s public declaration that the prophecy is fulfilled, right after Zeus’s confession, demonstrates another edge of the theme: prophecy can validate truth, but only after human courage drags that truth into daylight. Fate may pronounce, but people still have to risk everything to make the pronouncement real.

The novel keeps returning to the question of whether foresight guides action or cages it. Alexis’s decisions repeatedly reject passive obedience to “what will be.” Even when she suspects the dice are rigged in the Gladiator Competition, she plays along to keep Zeus exposed, choosing strategy over surrender.

In this way, Fate becomes a pressure system rather than a script: it pushes, distorts, and threatens to drown characters in inevitability, yet it cannot remove the need for will, sacrifice, and moral accounting.

Trauma, Survival, and the Cost of Power

Alexis’s body and mind carry the history of violence long before the plot’s wars begin. Her blind eye, damaged ear, and the chorus of dying voices in her head make trauma a living presence rather than a background detail.

Power in Bonds of Hercules is never clean; it is welded to memory, guilt, and survival habits formed in abuse. Her poison-like blood power, her ability to leap through space, and her growing reputation as Hercules are all linked to a past where strength became the only language that worked.

So even when Persephone offers a life of safety on Crete, Alexis cannot accept it, not because she loves suffering, but because her identity has been shaped in a world where ease equals vulnerability.

The narrative shows trauma as something that rewires desire and judgment. Alexis wants peace, yet her version of peace includes vengeance and control.

She is drawn toward the gladiator path because battle is familiar, and familiarity can feel like safety even when it is lethal. Her tendency to move toward screams in the Underworld tunnel, despite Nyx urging her to flee, shows how the injured self can become calibrated to crisis.

She does not seek danger for spectacle; she seeks it because ignoring it would mean repeating the helplessness that once defined her.

Kharon and Augustus are also marked by trauma that expresses itself through dominance, obsession, and fractured intimacy. Their marriage bond strengthens their powers while inflicting pain, mirroring how emotional bonds can become both anchor and wound.

Kharon’s furious execution of Hermos after Alexis is shot is not just possessiveness; it is a trauma response to the terror of losing the one person who now defines his sense of purpose. Augustus’s migraines, bleeding eyes, and the screaming victim voices he hears show a man being punished by his own history, unable to escape the bodily consequences of what he has done.

The book refuses to romanticize pain as a noble path to strength. Instead it tracks the price: insomnia in cramped cells, the inability to trust kindness, sexual dynamics that swing between comfort and re-enactment of control, and the constant sense that survival requires becoming harder than one wants to be.

Even a protector’s suffering, like Fluffy Jr.’s convulsions and possible molting, mirrors Alexis’s fear that her closest bonds may be dying inside transformations she can’t control. Power keeps them alive, but it also keeps reopening the same injuries.

The theme lands on a bleak truth: surviving violence can create extraordinary capability, yet that capability may feel like another chain unless the survivor finds a way to live beyond war.

Control, Betrayal, and the Politics of Truth

Authority in this world is built on manipulation of perception. Zeus’s regime depends less on raw strength than on narrative control: framing Medusa, arranging assassination attempts, rigging the labors dice, and maintaining a public face of lawful order.

The federation’s silence about war being held in check by mutually assured destruction shows a political structure that survives through managed fear. In Bonds of Hercules, betrayal is not a one-off twist; it is the operating system of empire.

Alexis’s decision to record Zeus and broadcast his confession is therefore revolutionary not merely because it exposes one tyrant, but because it demonstrates that truth can be weaponized against systems that have long monopolized it. The symposium scene turns a private accusation into a collective reckoning.

Importantly, Zeus’s fall is not caused by prophecy alone; it is caused by evidence combined with public witnessing. The story suggests that control collapses when lies are forced into the open where multiple factions must respond.

This theme also plays out at smaller scales. Patro and Achilles’s apparent mentorship hides personal agendas, sexual rivalry, and a sense of ownership over Alexis.

Their crack-away from the symposium to confront “Ceres” reveals how quickly allies can become enforcers when their worldview is threatened. Patro’s rage at Alexis for freeing Medusa shows betrayal as a matter of perspective: he thinks she betrayed Spartan security, while she believes she resisted Olympian corruption.

The moral landscape is unstable because loyalty is tied to competing definitions of safety and justice.

Even Alexis’s own deception—killing the real Ceres, disguising Medusa, staging a false breakout—forces the reader to sit with uncomfortable questions. She commits an act that would be monstrous in a different context, yet she sees it as necessary to protect someone framed by power.

The novel frames truth as something that sometimes requires dirty hands to survive. That does not excuse the violence, but it shows how corrupted systems corner people into choosing between ethical purity and effective resistance.

Kharon’s and Augustus’s marriages to Alexis are another form of control, initially justified as political protection for Chthonics. Yet that justification becomes indistinguishable from personal possession, and Alexis experiences it as captivity.

The story keeps asking where protection ends and domination begins. When Kharon supports letting the girls decide what to do with Ceres, it is a rare moment where a controlling framework loosens, hinting at the possibility of a different kind of loyalty.

The theme ultimately argues that betrayal is inevitable in a world where power thrives on secrecy. The counterforce is not blind trust, but courageous exposure—knowing that revealing the truth may fracture every bond you have, yet still doing it because living under a lie is worse.

Love, Bonding, and the Struggle for Autonomy

Relationships in Bonds of Hercules are built inside coercive structures—forced marriages, power-linked bonds, mentorship with possessive undertones, and alliances shaped by war. That environment makes love inseparable from questions of autonomy.

Alexis’s connection to Kharon and Augustus is physically intense and emotionally tangled, yet she repeatedly insists it is “just physical.” On the surface, that line is defensive; underneath, it is a demand to own her body and narrative after years of having both taken from her. Her stutter disappearing when she stops fearing them shows that fear had been governing her voice, and regaining speech is a form of reclaiming self.

Kharon and Augustus, for their part, do not understand autonomy as something that can coexist with their need to protect. Their devotion expresses itself through control: monitoring her safety, deciding where she sleeps, threatening consequences if she does not leap away from danger.

Their love is real, but it has grown in a culture where survival equals dominance. The marriage bond intensifies this problem by turning emotional attachment into a biological amplifier of power and pain.

The closer they are, the stronger and more tormented they become. That makes tenderness feel like risk, and control feel like care.

Other bonds echo the same tension. Persephone’s love for Alexis is gentle but also territorial, mediated through her ownership of Crete and her heightened sensing of every living thing there.

She offers shelter, yet her warning that the path back to Sparta will cost Alexis her soul positions love as a last appeal against self-destruction. Charlie’s bond with Alexis is quieter and more stable, rooted in shared survival rather than power games.

He functions as a reminder of a kind of love that does not require conquest.

Protectors deepen the theme by showing bonding outside romance. Fluffy Jr. is not merely a beast; he is an emotional tether for Alexis.

Her refusal to accept that his convulsions might be a tumor mirrors her refusal to accept that love can be mortal. Believing in his molting is an act of hope, almost a rebellion against the idea that the world always takes what she cares about.

The novel doesn’t present a neat resolution where love automatically heals. Instead it treats love as another battlefield: a place where people reenact trauma, negotiate safety, and test whether devotion can exist without ownership.

Alexis choosing mission partners other than her husbands is a crucial assertion of agency. So is her willingness to walk away from vengeance after stabbing her foster father, showing that autonomy also means deciding what kind of person she will be, not only whom she will be with.

The theme’s heartbeat is this ongoing fight to keep the self intact while still letting others close enough to matter.

Identity, Monstrosity, and Becoming More Than a Weapon

The characters in Bonds of Hercules live under labels that are both mythic and dehumanizing: Chthonic, Olympian, Gorgon, Titan-hunter, Hercules. Identity is treated as something assigned by bloodline, prophecy, and political need.

Alexis’s true name being Hercules ties her to a legacy of labors and public spectacle. When Ajax tears her toga and Zeus assigns her twelve labors with rigged dice, the humiliation is not random cruelty—it is an attempt to reduce her to a symbol: a weapon for the arena, a story for the crowd, a target for fear.

Her strategy of pretending acceptance signals that she refuses to be only what others name her.

Monstrosity is a social category as much as a biological one. Agatha’s revealed Gorgon visage triggers prejudice from Patro, showing how quickly “monster” becomes a reason to deny someone complexity.

Medusa’s treatment is the most extreme example: feared not for proven crimes, but for what her existence threatens in the balance of power. Her snakes and Fate-gift make her a walking accusation against Olympian rule.

The federation’s eventual pardon is conditional and academic—she must study Fate under supervision—suggesting that even when innocence is acknowledged, the system still tries to domesticate what it cannot kill.

Alexis’s inner chorus of dead voices keeps the idea of monstrosity inside her as well. She has killed many, and the story never lets her forget it.

Yet it also shows that “monster” can mean someone forced into violence by cruelty. Her childhood abuse, her killing of her foster mother to protect Charlie, and her later choice to free Medusa all complicate simple moral branding.

She is terrifying, but she is also someone trying to protect what little goodness she can still recognize.

Becoming “more” than a weapon is framed as both personal and political. Hades’s line that “no one fears the sane” pushes Spartans toward legend, implying that sanity and softness are liabilities.

The book challenges this by showing that legend without conscience becomes tyranny. Alexis’s exposure of Zeus, her defense of Medusa, and her refusal to allow Patro to violate a traumatized prisoner for information are moments where she asserts a self beyond battle utility.

The closing prophecy about a “lost one” changing Sparta and a “monstrous one” mending and restoring points to a future where the very traits that made certain people feared may be what saves their world. Identity here is not destiny stamped at birth; it is something fought for under pressure.

The theme insists that the path from monster to healer is not a transformation into something safer for others—it is a transformation into something truer for oneself, even if the world remains scared of what that truth looks like.