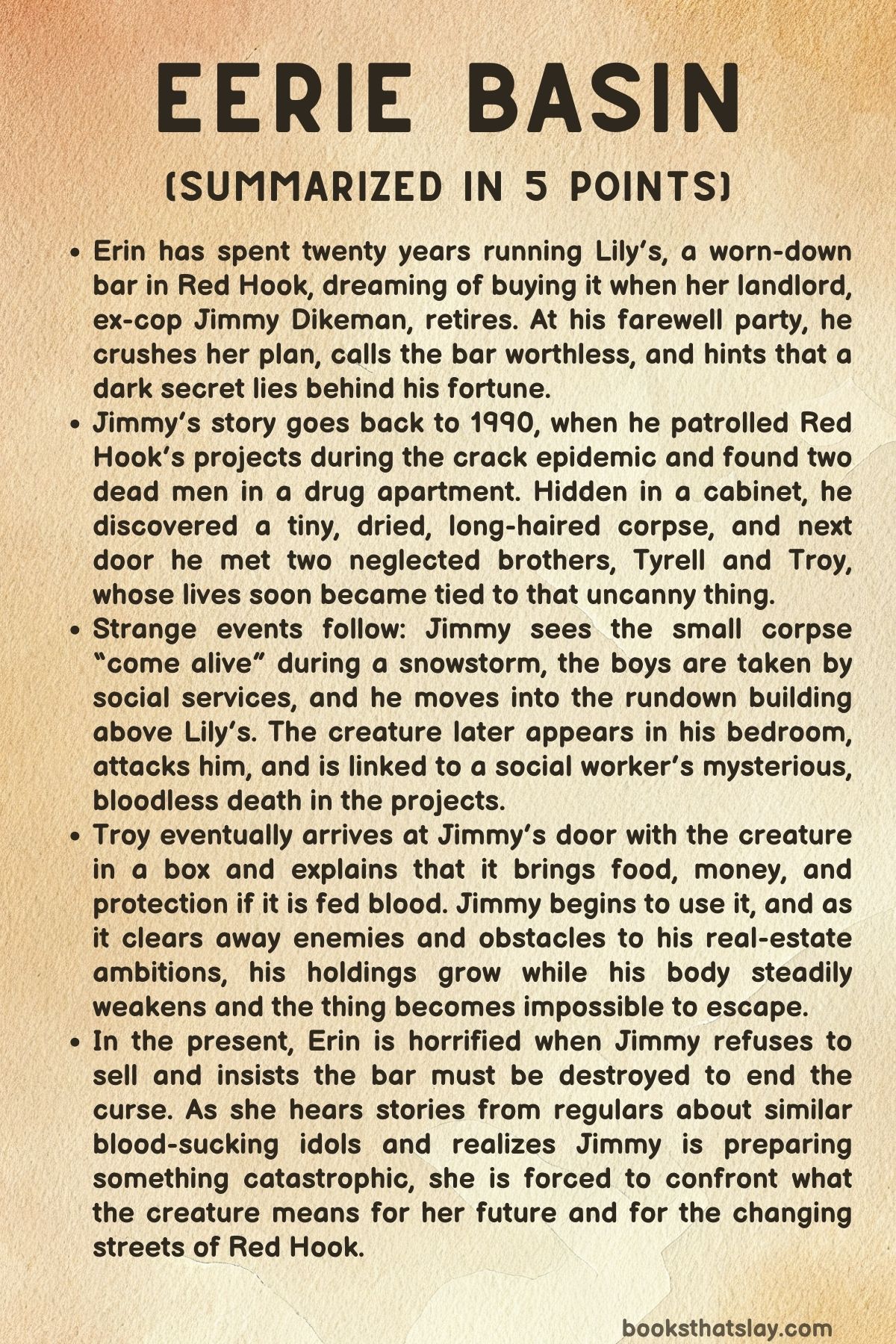

Eerie Basin by Ivy Pochoda Summary, Characters and Themes

Eerie Basin by Ivy Pochoda is a dark, slow-burn horror story set in the changing streets of Red Hook, Brooklyn. At its center is Lily’s, a worn-out neighborhood bar clinging to life as condos and fancy shops close in.

The story follows Erin, a stubborn bartender who has built her world around this place, and Jimmy Dikeman, a former cop turned landlord whose success hides something truly monstrous. Through their connection to a sinister Indonesian relic that trades blood for power, Eerie Basin explores gentrification, complicity, and the terrible bargains people make to survive and stay in control.

Summary

Erin has been behind the bar at Lily’s in Red Hook for two decades, serving regulars, breaking up fights, and keeping a dying neighborhood institution afloat. The world outside has changed: old warehouses have become sleek apartments; a fancy grocery store and boutiques have pushed out the docks and diners.

Lily’s looks like a relic, but for Erin it is home, future, and identity. She has scrimped and saved in secret, planning to buy the building from its owner, Jimmy Dikeman, once he retires and moves to Florida.

Jimmy is a former cop who turned his insider knowledge of the neighborhood into a real-estate empire. He owns Lily’s building along with several flashy properties along the waterfront.

On the night of his retirement party, with the regulars gathered and Jimmy basking in farewells, Erin finally reveals her surprise: a detailed plan to buy Lily’s, renovate just enough to survive, and keep it a true neighborhood bar. It is her dream and the payoff for twenty years of loyalty.

Instead of being impressed, Jimmy laughs in her face. He calls the bar worthless and says the building is coming down.

There will be no sale, no future for Lily’s, and no reward for Erin’s sacrifice. When she demands to know why, he decides to finally tell her how he really got rich—and why the building must not outlive him.

Jimmy’s story begins in 1990, when he is transferred to patrol the Red Hook projects during the crack epidemic. Violence is constant, the buildings are crumbling, and the police mostly move through like an occupying force.

After a drive-by shooting, Jimmy and his partner enter a drug apartment looking for suspects. Instead they find two dead men, the usual chaos of a crack den, and something stranger: in a cabinet, a tiny long-haired corpse, dried out and doll-like, with the proportions of a small person.

Next door live two boys, Tyrell and his younger brother Troy, alone and desperate. Their mother is gone, their food is scarce, and no one in the building seems to care.

Jimmy breaks the rules and quietly looks out for them, slipping them food and leaving the abandoned drug apartment open so they can raid it for supplies.

A few weeks later, he spots Troy carrying the little corpse like a toy. The sight unnerves him, but he lets it go.

On New Year’s Eve, during a snowstorm, he finds Troy alone in the boys’ freezing apartment—Tyrell has been hospitalized. Jimmy stays the night to keep the kid safe while men pound on the door, threatening them for stealing from the dealers.

Half asleep on the floor, he experiences something he cannot explain: he sees the tiny corpse get up, shuffle across the room, and open the door. When he fully wakes, Troy is clutching a fistful of the thing’s hair, and the small skeleton now lies tucked into Tyrell’s bed.

Alarmed, Jimmy reports the boys to social services. Troy is sent to the hospital, where doctors are baffled: he is severely anemic despite eating well.

At the same time, Jimmy’s own life is falling apart. His marriage is collapsing, and he moves into the decaying building that will later house Lily’s, buying it cheap.

One night, the same small creature appears in his bedroom. It crawls up his chest and bites him.

Jimmy traps it in a pillowcase and shoves it into the oven, only to find it gone by morning. Soon after, the social worker who handled the boys’ case is found dead in the projects’ lobby, her body strangely bloodless.

Months pass. Then Troy shows up at Jimmy’s door with a box.

Inside is the creature, no longer just a dried corpse but something clearly alive in its own disturbing way. Troy explains what he and Tyrell have learned: the creature gives money, food, and protection to whoever owns it, as long as it is fed blood.

First it accepted animal blood, then it demanded more. When it is not fed, it hunts on its own.

Whoever feeds it becomes its master—until they manage to pass it on. Troy is terrified that Tyrell will keep offering their blood, sacrificing them both.

He begs Jimmy to take the creature and destroy it, warning him never to feed it.

That same night, Jimmy sees the creature trying to leave his apartment, likely returning to the boys. In a panic, he offers his own wrist to keep it from escaping.

It feeds on him. Days later, Jimmy’s old captain, who has blocked his promotion for years, dies in a strange “rat attack.” With the captain gone, Jimmy’s promotion suddenly goes through.

He gets a pay raise, new status, and access to better loans. With this boost, he buys a waterfront warehouse, then more buildings.

Jimmy begins to understand the pattern. Whenever someone stands in the way of a deal—a seller, a bureaucrat, a rival—the creature can remove them.

Fires break out. “Accidents” happen.

People die in ways that make no sense. Each time, Jimmy has given more of his blood.

His body starts to fail. He is powerful and sick at the same time, bound to the creature he cannot quite destroy.

He tries to get rid of it, but it always finds its way back. Eventually he resigns himself to the idea that the only way to end its influence is to die with it, and to make sure no one inherits the building that shelters it.

Back in the present, Erin vents her anger to regulars Gina and Toni. She tells them Jimmy refused to sell and tried to scare her off with a story about a walking corpse.

Toni remarks that people who get mixed up with Jimmy’s deals never seem to thrive. Gina reacts more strongly.

She tells a family story about her mob-boss grandfather, who once owned an Indonesian blood-sucking idol known as a jenglot. The idol made him rich and feared, while draining his health.

When Gina’s grandmother tried to have it exorcised, the family’s power collapsed. Gina is convinced that the same jenglot eventually passed into the projects, then to Jimmy.

After closing, Jimmy again urges Erin to walk away—not just from Lily’s, but from Red Hook altogether. He still refuses to sell.

Once he leaves, Erin, shaken and angry, goes upstairs into his apartment. There she finds gas cans and propane tanks hidden in closets and corners.

The plan is obvious: Jimmy intends to burn the building down, killing himself and the jenglot and wiping Lily’s off the map.

Feeling betrayed and stranded, Erin heads out into the night. She walks along the waterfront, past Jimmy’s warehouses, to his gleaming Fairway building.

Nearby, in an abandoned trolley car, she finds him slumped and barely alive. The jenglot is on his chest, feeding on him like a parasite finally finishing its host.

Erin stands there and does nothing to help him.

When the creature, bloated on Jimmy’s blood, staggers toward her, Erin does not run. She is empty of illusions about loyalty, hard work, or fairness, and she is drawn to the raw power the jenglot represents.

With Lily’s doomed and her future in ruins, she holds out her wrist. As it feeds, she feels a surge of energy and possibility.

She realizes that Jimmy will die, the jenglot will attach itself to her, and she will walk back into Red Hook with a dangerous new ally. What she will do with that power—and what it will cost her—is the shadow hanging over whatever comes next.

Characters

Erin

Erin is the emotional center of Eerie Basin, the person most deeply rooted in Lily’s and in Red Hook’s older, rougher identity. She has spent twenty years tending bar at Lily’s, holding together a shabby space that functions as a refuge for regulars who do not fit into the polished, gentrified Brooklyn around them.

Her quiet discipline is revealed in the way she has secretly saved enough money to buy the bar; she is not just a sentimental caretaker, but a planner who believes in work, loyalty, and the slow accumulation of small gains. The shock when Jimmy mocks her plan and calls Lily’s worthless exposes how precarious her life really is: everything she has built depends on someone else’s hidden story and on structures of power she never fully understood.

At the same time, Erin is not simply a victim. Her decision at the end—to let the jenglot feed on Jimmy and then willingly offer it her own wrist—exposes a complex mixture of anger, desperation, and ambition.

She feels betrayed by Jimmy’s schemes to burn down the building and erase Lily’s, but she also sees in the jenglot a tool to rewrite the future of Red Hook. In that moment she stops trying to work within the rules of landlords, permits, and slow savings and instead embraces the same dangerous shortcut Jimmy used, but with eyes open.

She is drawn to the rush of possibility the jenglot offers, suggesting that beneath her loyalty and patience there has always been a hunger to shape the neighborhood, not merely to survive in it.

Erin’s moral arc is deliberately ambiguous. Watching Jimmy die without intervening suggests a ruthless streak; she allows the curse to claim him precisely because it makes room for her own ascent.

Yet the choice is also shaped by grief and exhaustion: after discovering the gas cans and realizing that Jimmy is willing to sacrifice her bar and her future, she understands that the system has already written her out. By accepting the jenglot, she chooses to become an active agent rather than another casualty.

Erin’s character therefore holds the unsettling question at the heart of Eerie Basin: when the world is rigged against you, what compromises and monstrosities are you willing to accept in order to finally hold power?

Jimmy Dikeman

Jimmy begins as a familiar figure: a former cop turned landlord, a man who has leveraged institutional authority into private property. But in Eerie Basin, his rise is inseparable from supernatural corruption.

The young Jimmy we see in 1990 is complicated. He brings food to Tyrell and Troy, leaves the drug apartment open to them, and spends a terrifying New Year’s Eve guarding Troy from the men pounding on the door.

These actions suggest a genuine desire to protect vulnerable kids in a brutal environment, or at least a paternalistic sense of responsibility. Yet even at his most sympathetic, Jimmy is operating inside a system that allows him to profit from others’ suffering; he soon moves into the building above Lily’s and buys it cheaply while the boys are absorbed into the machinery of social services.

The jenglot amplifies traits that are already present in him: ambition, resentment, and a need to prove himself. When he first feeds it and sees his hated former captain die in a gruesome “rat attack,” followed by his own promotion, he learns that shortcuts work and that violence can be outsourced to something deniable and otherworldly.

From there, his empire is built on a series of “necessary” sacrifices: a seller who will not budge, an official who blocks a permit. Jimmy tells himself he is just using what fate has put in his path, that he has to keep feeding the creature to maintain what he has built, but his body wasting away makes visible the moral and physical cost.

He becomes both master and slave of the jenglot, ostensibly controlling it while in reality having his life devoured to sustain his own power.

By the time we reach the present, Jimmy is a tragic figure who recognizes the curse too late. His plan to burn down Lily’s and die with the jenglot is an attempt at atonement, but it is also another act of collateral damage; he is willing to annihilate Erin’s dream to end his torment.

When he urges Erin to leave Red Hook, he is torn between wanting to protect her and wanting to clear the stage for his final gesture. His death, slumped in the trolley car with the jenglot on his chest, feels less like a heroic sacrifice and more like the inevitable end of a man who tried to ride a monster for decades.

Jimmy embodies a certain kind of urban power broker: outwardly respectable, shaped by the police and property systems, yet built on hidden violence and on the quiet exploitation of the poor.

Troy

Troy, the younger of the two brothers, embodies the perspective of a child trying to navigate hunger, violence, and the allure of supernatural protection. When Jimmy first encounters him, Troy is cradling the tiny skeleton like a toy, which suggests a disturbing intimacy with the jenglot but also a child’s attempt to find comfort in the only “companion” available.

He is living in a world where adults are absent or predatory, and the creature is both a source of fear and a provider of real benefits: food, money, safety from the dealers. That ambiguous bond is captured in the New Year’s Eve sequence, where the jenglot seems to move of its own accord while Troy clutches its hair; Troy’s reality is already blurred between nightmare and survival strategy.

As he grows older, Troy’s moral awareness deepens. When he later appears at Jimmy’s door with the box and begs him to take the jenglot, Troy is trying to break the cycle he and Tyrell have been trapped in.

His explanation—that the creature must be fed, that it escalates from animals to people, that it hunts on its own if starving—reveals that he has been complicit in feeding it but is also terrified of what it demands. More importantly, he fears that his older brother will continue to sacrifice them both to maintain the creature’s protection and the small, crooked advantages it offers.

Troy’s decision to give the jenglot away is a desperate act of resistance, an attempt to shift the burden to someone he believes might have the power to destroy it.

Troy’s character highlights how the curse of the jenglot is not just a metaphor for greedy landlords and mob bosses; it is also a pattern of intergenerational trauma passed through vulnerable families. He has been raised inside a logic where blood is a currency and safety is always conditional.

His plea to Jimmy—“never feed it”—is both a warning and a test of trust. Unfortunately, Jimmy fails that test almost immediately, proving how adults and institutions repeatedly betray children like Troy.

In this sense, Troy stands as one of the novel’s most quietly heartbreaking figures: a boy who recognizes evil and tries to stop it, only to watch another adult succumb to the same temptation.

Tyrell

Tyrell, the older brother, appears less frequently in the summary but exerts a powerful presence as both victim and potential perpetrator. When Jimmy first encounters the boys, Tyrell is the de facto guardian, the one responsible for keeping his younger brother alive in an environment ravaged by the crack epidemic.

His hospitalization on New Year’s Eve leaves Troy alone, and that absence underscores how fragile their survival structure is; one illness or injury can collapse the entire system. The fact that the jenglot ends up tucked into Tyrell’s bed while he is in the hospital suggests that the creature is being woven into the boys’ sense of family and protection, a replacement for the adults who fail them.

By the time Troy returns to Jimmy, the fear that “his brother will keep sacrificing them” hints that Tyrell has embraced the jenglot’s logic more fully. Whether he is willing to shed others’ blood, or simply unable to let go of the power it provides, Tyrell represents the way long-term exposure to violence and scarcity can twist a person’s moral compass.

He is not depicted as a cartoonish villain; his choices likely arise from the same desperation Troy feels. But where Troy tries to escape, Tyrell seems rooted in the belief that the jenglot is their only path to survival or advancement.

That divergence between the brothers mirrors the split we later see between Jimmy and Erin in how they respond to the creature.

Tyrell thus functions in Eerie Basin as a shadowy forerunner of characters like Jimmy and Erin: someone at an earlier stage of the same moral crossroads. The brief glimpses we get of him invite the reader to imagine a whole offstage history of compromises, justifications, and rationalizations.

His trajectory warns that once you accept blood as a price for safety, it becomes harder and harder to step away from the bargain, especially when you are the one responsible for another person’s life.

Gina

Gina acts as a crucial bridge between the supernatural story and the broader history of power and crime that underlies Eerie Basin. As the granddaughter of a mob boss who once owned an Indonesian blood-sucking idol, she carries a family memory of the jenglot long before it arrives in Red Hook’s projects or in Jimmy’s apartment.

Her recollection that the idol brought power while slowly killing her grandfather echoes Jimmy’s experience almost perfectly, suggesting that the creature is not tied to a single person or place but to a recurring pattern: the temptation to trade blood for influence. When she recalls how her grandmother’s attempt to have it exorcised coincided with the family’s fall from power, Gina reveals how tightly the jenglot is woven into their identity and status.

At the same time, Gina is more than a storyteller. Her shaken reaction to Jimmy’s tale shows that she recognizes the danger and reality of the jenglot, not just as folklore but as an active presence that keeps resurfacing.

She sees the cursed pattern in Jimmy’s luck and the misfortunes of those who deal with him, and her insight gives Erin—and the reader—a lens through which to interpret the bar’s precarious position. Gina is rooted in Lily’s as a regular, part of the bar’s informal family, and this social position enables her to connect private stories of supernatural horror with the neighborhood’s visible shifts in wealth and power.

In many ways, Gina functions as a chorus, commenting on the action and supplying background that complicates easy explanations. She suggests that what is happening in Red Hook is not unique but part of a longer lineage of cursed bargains stretching across oceans and generations.

Her character embodies the uneasy knowledge shared by those who live close to crime and power: nothing is free, and every “miracle” of wealth or protection is paid for by someone’s suffering, often hidden from public view.

Toni

Toni is another of Lily’s regulars, and while she may not have the mythic connection to the jenglot that Gina does, she serves an important role as the voice of neighborhood rumor and common sense. Her observation that people who deal with Jimmy always seem cursed is less a formal accusation than an instinctive pattern recognition.

Toni’s comments capture the way ordinary residents notice the strange coincidences and misfortunes around powerful figures long before any official narrative acknowledges them. She gives language to the neighborhood’s suspicion that Jimmy’s success has come at an unnatural cost.

Toni’s presence also deepens our understanding of Lily’s as a community hub. When Erin vents about Jimmy’s refusal to sell and his bizarre story of a walking corpse, Toni’s response shows how stories circulate in such spaces, merging gossip, superstition, and real fear.

She helps validate Erin’s unease, even if she cannot fully explain it. Together with Gina, Toni represents the collective consciousness of Red Hook’s old guard, the people who have seen enough to know that sudden wealth and rapid development always have a darker side.

In the larger architecture of Eerie Basin, Toni grounds the supernatural plot in the everyday. Her skepticism, humor, and sharp observations keep the narrative anchored in a bar stool reality, reminding us that for most people the curse of the jenglot is experienced not as a direct bite but as job loss, displacement, or unexplained misfortune when someone like Jimmy makes another deal to keep his empire growing.

Gina’s Grandfather

Gina’s mob-boss grandfather appears indirectly through her story, but he is a key figure in the jenglot’s journey and in the novel’s exploration of power. As a powerful criminal who uses the Indonesian idol to consolidate and expand his influence, he represents an earlier era of masculine authority built on violence and fear.

The jenglot does not change his essential nature; it acts as an amplifier, allowing him to do more of what he already does while slowly draining his life. His physical weakening as his power grows creates a grim irony: the more he wins in the external world, the more he loses in his body.

Through him, Eerie Basin suggests that the jenglot is drawn to people who already inhabit morally compromised roles. It does not create corruption out of nowhere; it attaches itself to those who are willing to pay in blood to keep their status.

Gina’s story implies that her grandfather accepted this bargain willingly, valuing dominance over health or longevity. His eventual downfall, coinciding with his wife’s attempt to exorcise the jenglot, illustrates how fragile such power really is once its supernatural scaffolding is removed.

He stands as an earlier version of Jimmy, foreshadowing what happens when a man builds his legacy on a secret hunger that can never be fully satisfied.

Gina’s Grandmother

Gina’s grandmother is a quieter but morally significant figure. She is the one who tries to have the jenglot exorcised, effectively choosing the loss of the family’s supernatural advantage in exchange for ending the blood-soaked bargain.

Her actions introduce the possibility of resistance into the novel’s pattern of cursed inheritance. Unlike her husband, she is willing to accept a decline in status, wealth, or influence if it means severing the connection to the creature that is killing them from within.

However, the family’s subsequent loss of power complicates her role. To those who valued the old dominance, she might appear responsible for their downfall, the one who “ruined” everything by casting out the source of their strength.

This tension echoes the broader dynamics in Eerie Basin between those who want to root out corrupt systems and those who fear the instability that change brings. Gina’s grandmother shows that rejecting the jenglot is possible, but the price is steep and the cost is borne not just by the individual but by the entire family network.

Her presence in the story raises the painful question of whether Erin, or anyone, will ever be willing to pay a similar price.

The Jenglot

The jenglot is both a supernatural monster and a symbol that threads together the lives of all the human characters in Eerie Basin. Physically, it begins as a tiny, dried, long-haired corpse, unsettling precisely because it is small and ambiguous, like a shriveled child or a discarded relic.

Its movements blur the line between dream and reality: Jimmy thinks he “dreams” it walking across the floor and opening the door, yet he wakes to tangible signs of its intervention. It can be contained in a cabinet or a pillowcase, shoved into an oven and somehow escape, carried in a box like contraband, then suddenly animate to hunt, feed, or return to its “owner.” This elusive behavior emphasizes that it is not a pet or a simple tool; it has its own will and its own needs.

The rules Troy explains make the jenglot’s logic brutally clear. It offers concrete, material benefits—food for starving boys, protection from violent dealers, promotions and real-estate deals for Jimmy—in exchange for blood.

At first, the price can be managed by feeding it animals, but the demand escalates to humans, and if its needs are not met, it hunts on its own, leaving bodies that appear oddly bloodless. This escalating appetite mirrors the way greed, addiction, or unchecked development always demand more: more land, more profit, more sacrifices that can be justified as necessary casualties.

The jenglot is the embodiment of a parasitic form of success, one that feeds off the life of individuals and communities.

Importantly, the jenglot passes from owner to owner: from Gina’s grandfather to the boys, from the boys to Jimmy, and finally from Jimmy to Erin. It is not destroyed by individual deaths or personal regrets; it simply attaches to someone new who is desperate enough to accept its terms.

This pattern suggests that the real “curse” is not a single creature but a recurring structure of power in which people believe they must trade something vital—blood, conscience, community spaces like Lily’s—to gain protection or advancement. When Erin feels a rush of possibility as it feeds on her wrist, the jenglot’s allure becomes painfully understandable.

It offers not vague promises but immediate agency in a world where the deck is stacked. As long as that world remains unjust, the creature will always find someone willing to let it feed.

Themes

Power, Corruption, and the Logic of Bargains

From the moment Jimmy offers his wrist to the jenglot, Eerie Basin treats power as something never acquired cleanly. Jimmy begins as a frustrated, overlooked cop, embittered by his stalled promotion and the chaos of the crack era in Red Hook.

The jenglot arrives as an answer to his grievances: a shortcut around bureaucratic humiliation, a way to rise above the neighborhood’s decay. Every “success” that follows—his promotion, the purchase of his first warehouse, the expansion of his real-estate empire—is stained by blood, quite literally paid for with his own body.

Power is framed not as a reward for virtue or hard work, but as a series of exchanges where the price is hidden at the start and revealed, too late, in physical and moral ruin.

Crucially, Jimmy’s corruption is not caricatured. He feeds the creature first out of fear and then out of rationalization, convincing himself that the deaths it causes are either deserved or inevitable.

When an obstructive superior dies in a horrific “rat attack,” Jimmy experiences not horror but grim satisfaction and relief. The narrative suggests that corruption often begins with small allowances: a drop of blood here, a justified death there.

Once he accepts that the jenglot can “solve problems,” every new obstacle invites a little more compromise. Jimmy’s role as landlord intensifies this dynamic.

His properties, bought through occult violence, become the visible face of his invisible pact. The neighborhood’s gentrification is thus shown as structurally linked to a supernatural economy of harm.

By the time Jimmy tries to destroy the jenglot by dying with it and burning the building, his attempt at atonement is itself compromised: he is still deciding who deserves to live and who must lose everything. His plan would erase Lily’s and ruin Erin’s future without her consent, continuing the same pattern of making choices over other people’s lives in order to manage his own guilt.

Power in Eerie Basin is never neutral; it always bears the mark of the bargains that brought it into being, and once those bargains begin, they are almost impossible to undo.

Gentrification, Real Estate, and the Violence of Urban Change

Red Hook in Eerie Basin is not just a backdrop; it is a contested zone where capital, memory, and survival constantly collide. Lily’s, with its shabby barstools and long history, represents a version of the neighborhood rooted in working-class continuity, habits, and local relationships.

Around it, new condos and shops rise, purchased and assembled by the very man whose secret pact with the jenglot fuels this transformation. Gentrification here is not described as an abstract economic process, but as a chain of individual decisions tied to harm: each building Jimmy acquires has, somewhere in its history, a trail of blood and unexplained disaster.

The violence of urban change is both literal and symbolic. Fires, accidents, and sudden deaths clear the way for development, dramatizing the way marginalized residents often vanish from neighborhoods undergoing “renewal.” The projects where Tyrell and Troy once lived are a reservoir of forgotten suffering, a place where boys can starve unseen and a social worker can die “oddly bloodless” without seriously interrupting the city’s narrative of progress.

Jimmy’s waterfront warehouses and gleaming Fairway building stand as trophies of a victory nobody in the neighborhood actually asked for. They are monuments to a prosperity that erases its own origin story.

Erin’s attachment to Lily’s complicates the usual gentrification script. She has worked there for twenty years, kept the bar alive during worse times, and painstakingly saved enough to buy it.

She is not a wealthy outsider, but she still longs to secure ownership in a landscape where property equals security and voice. Jimmy’s refusal to sell, and his plan to demolish the building entirely, shows how the power to shape the neighborhood’s future is concentrated in a small set of hands—hands already stained by supernatural violence.

By the novel’s end, when Erin offers her wrist to the jenglot, the question becomes whether the next phase of Red Hook’s transformation will repeat Jimmy’s brutal pattern or redirect that energy. The neighborhood’s fate is linked to who controls the creature, and therefore who controls the invisible forces behind the changing skyline.

Hunger, Scarcity, and an Economy of Blood

Hunger appears in Eerie Basin long before the jenglot begins feeding. Tyrell and Troy live in a near-empty apartment, half-starving, reliant on whatever scraps Jimmy allows them to take from the drug apartment next door.

Their hunger is physical and immediate—empty cupboards, freezing rooms, desperation that makes theft feel like a necessity rather than a crime. When Troy is later found severely anemic despite eating well in the hospital, that original hunger has taken on a new, more sinister form.

The jenglot has converted a scarcity of food into a more profound scarcity of blood, draining him even as his stomach is finally full.

The creature’s demands mirror the economics of the neighborhood. It promises protection, money, and food in exchange for a resource that seems abundant—blood.

At first, its owners can pretend the exchange is fair, even generous. The boys feed it from animals and perhaps from people they perceive as threats; Jimmy offers his own blood and tells himself that the deaths it causes are ultimately beneficial to him and even to the community, clearing away criminals or corrupt officials.

Over time, though, the creature makes it clear that its appetite is endless. Houses, promotions, and power all sit atop an invisible ledger of withdrawals taken from bodies in the form of drained lives and failing health.

Erin’s relationship to hunger is more subtle but just as real. She is not starving in a literal sense, but she is hungry for stability, for ownership, for proof that her two decades at Lily’s mean something more than a paycheck.

Jimmy’s dismissal of the bar as “worthless” exposes how precarious her investment in the place has always been. Her savings, her loyalty, and her labor are no match for a landlord’s whims.

When she finally offers her wrist to the jenglot, that gesture can be read as the moment her emotional hunger finds a terrifying outlet. She chooses to enter the same economy of blood that trapped Troy and Jimmy, gambling that the creature’s power will finally feed the needs that the ordinary world has ignored.

The novel suggests that in systems built on deprivation and exclusion, supernatural bargains are only an exaggerated version of the deals people already make to satisfy hunger—whether for food, safety, or a future.

Complicity, Moral Compromise, and the Stories People Tell Themselves

Throughout Eerie Basin, characters survive by telling themselves particular stories about what they have done and why. Jimmy thinks of himself as a man who tried to help Tyrell and Troy at the beginning—leaving doors unlocked, bringing food, staying the night in their freezing apartment.

Those early gestures form the backbone of his self-image, even as his later actions grow steadily more abhorrent. When the jenglot starts killing obstacles in his path, he accepts the benefits and mentally distances himself from the costs.

The deaths are accidents, or they happen to people who “had it coming,” or they are just the price of getting important work done. His complicity deepens each time he allows the creature to act without intervening or seeking genuine help.

Erin’s complicity is more compressed in time but equally significant. When she finds the gas cans and realizes Jimmy plans to burn the building, she experiences a rush of fury and despair rather than immediate alarm for his mental state.

The idea of losing Lily’s feels like a betrayal after decades of loyalty and invisible labor. Later, in the trolley car, she watches Jimmy while the jenglot drains him and chooses not to intervene.

That inaction is a moral decision as consequential as any of Jimmy’s active choices. She becomes a witness who refuses rescue, allowing the creature to finish the work that years of small compromises began.

When the jenglot staggers toward her and she offers her wrist, Erin crosses from outraged victim to willing participant.

The novel thus portrays complicity as something built gradually out of fear, resentment, and desire, rather than a single decisive act of evil. Both Jimmy and Erin step over lines because each new step feels like a logical extension of the last.

The supernatural element emphasizes how easy it is to outsource responsibility to forces that seem larger than oneself—whether those forces are creatures, institutions, or markets. Yet the book insists that the characters’ choices matter.

Jimmy could have refused to feed the jenglot, could have confessed, could have walked away from deals that required blood. Erin could have called for help, walked out of the trolley car, rejected the offer of power.

Their failure to do so exposes how the stories they tell themselves—about being cornered, about having “no choice”—are part of the machinery that keeps harm in motion.

The Body as Collateral: Extraction, Illness, and Decay

Bodies in Eerie Basin are treated like accounts from which value can be withdrawn. Troy’s anemia, the bloodless corpse of the social worker, Jimmy’s wasted frame, and finally the debilitation that overtakes him as his empire grows all point to a world where success is paid for in flesh.

The jenglot is a literalization of extraction: it drinks blood in exchange for material and social advantages. Yet its presence also draws attention to the less obvious ways the characters’ bodies are used up by their environment.

The boys’ malnutrition is a result of systemic neglect long before the creature enters their lives. Jimmy’s stress, insomnia, and physical decline could be read as symptoms of a policing and property regime that demands constant sacrifice from those who serve it.

The jenglot’s method of feeding blurs the line between voluntary and involuntary harm. When Jimmy first offers his wrist, he chooses to allow his own body to be drained.

That act feels, to him, like control: if someone must be hurt, better that it be himself than the boys. Over time, however, the creature’s hold over him becomes more coercive, and his “choice” looks more like addiction or bondage.

He is locked in a cycle where he must keep feeding it to keep his gains safe, even as the cost to his body accelerates. The organism can also hunt on its own if not fed, which means that Jimmy’s sacrifices are also an attempt to protect others from random attacks—a twisted repetition of his original role as a cop.

By the time Erin steps forward to offer her wrist, the theme of the body as collateral has shifted toward questions of agency. She has watched what the jenglot did to Jimmy, and she has heard Gina’s story of her grandfather’s slow destruction under a similar idol.

She cannot pretend ignorance. Her willingness to be bitten is therefore not naïve but defiant, a conscious wager that she can manage the cost better than the men before her or at least accept it as the price of rewriting her life in Red Hook.

The book uses these bodily transactions to ask what it means to stake one’s health, blood, or safety on a future that might never arrive—and whether, in a world shaped by exploitation, anyone truly escapes such stakes.

Haunting, Curses, and the Persistence of History

The jenglot is more than a monster in Eerie Basin; it is a carrier of history, moving from Gina’s mob family to the boys in the projects, and from them to Jimmy and then to Erin. Each transfer layers new stories onto the object.

Gina’s grandfather uses it to consolidate criminal power, and when her grandmother tries to have it exorcised, the family’s influence collapses. The creature vanishes only to resurface years later in a completely different context, as if drawn to spaces marked by desperation and ambition.

Its arrival in Red Hook’s projects suggests that the forces that once empowered organized crime have not disappeared but have migrated, adjusting to new forms of marginalization and urban neglect.

Jimmy’s experiences with the jenglot often take the form of hauntings. It appears in his bedroom, crawls up his chest, bites him, and then refuses to stay dead even when he tries to burn it in the oven.

Later, he dreams—or believes he dreams—of it walking across the floor and opening the boys’ door. These episodes blur the line between guilt, nightmare, and supernatural reality.

The creature becomes a physical manifestation of memories Jimmy cannot escape: the freezing apartment, the boys’ terror, the social worker’s death. No matter how high he climbs as landlord and investor, the jenglot returns to remind him that his wealth is built on unresolved harm.

Erin’s encounter at the end signals that the curse is not ending but changing hands. She recognizes that once Jimmy dies, the jenglot will follow her home, and she accepts that fate.

The haunting shifts focus, from a man trying to outrun his past to a woman prepared to wield that past as a weapon and a tool. The question is no longer whether the curse can be broken, but what kind of future can be built with something so loaded with history.

By tracing the jenglot’s path across families, classes, and generations, Eerie Basin suggests that communities are haunted by cycles of exploitation and power that move from era to era under new names. Exorcism attempts may temporarily quiet these forces, but unless the underlying patterns of greed, neglect, and violence are confronted, the curse simply finds a new host.

Ownership, Legacy, and Who Gets to Shape the Future

From the opening pages, Eerie Basin frames ownership as the central battleground for its characters’ hopes. Erin has spent two decades keeping Lily’s alive, not merely as a job but as a project of care and continuity.

She assumes that this dedication, combined with her hidden savings, has earned her a stake in the bar’s future. Jimmy, on the other hand, treats ownership as a legal and financial fact: he bought the building cheaply years ago, using the jenglot’s power and his position as a cop to secure deals others could not.

In his view, the bar is just another asset, and tearing it down is a rational move toward a more profitable or manageable future. This conflict lays bare a larger question: who has the right to decide what parts of a neighborhood survive?

Jimmy’s planned demolition of Lily’s is a form of erasure, not only of the bar but of Erin’s imagined legacy. She has envisioned herself as the next in a line of caretakers; he sees her as a tenant whose time is up.

His motive is entangled with his desire to die with the jenglot and prevent anyone else from inheriting the curse. Even in this apparently self-sacrificial plan, he claims the authority to decide the bar’s fate and, by extension, the fate of those who rely on it.

Ownership in this sense includes the power to destroy, to cut off possible futures for others in the name of personal redemption.

The transfer of the jenglot at the end reconfigures the question of legacy. Jimmy’s real-estate empire will likely pass into other hands through official channels, but the true engine behind that empire—the creature—moves privately to Erin.

She becomes, in effect, the new author of Red Hook’s next chapter, armed with a tool that can rearrange the neighborhood’s power relations as dramatically as Jimmy once did. Her acceptance of the jenglot is thrilling and terrifying because it opens the possibility that she will use it to defend the community, punish exploiters, or secure Lily’s symbolic successor—yet the pattern of blood-for-influence suggests that any such legacy will be compromised.

The novel closes with Erin poised between the desire to protect what she loves and the temptation to remake Red Hook according to her own vision, mirroring the choices Jimmy once faced. In doing so, Eerie Basin makes ownership not just a matter of deeds and titles, but a moral question about what kind of future one is willing to build and what one is willing to sacrifice to build it.