Enshittification Summary and Analysis

Enshittification by Cory Doctorow is a furious, funny, and very clear-eyed tour of how the modern tech world went rotten. Doctorow argues that platforms do not simply “get worse” by accident or because of a few bad CEOs.

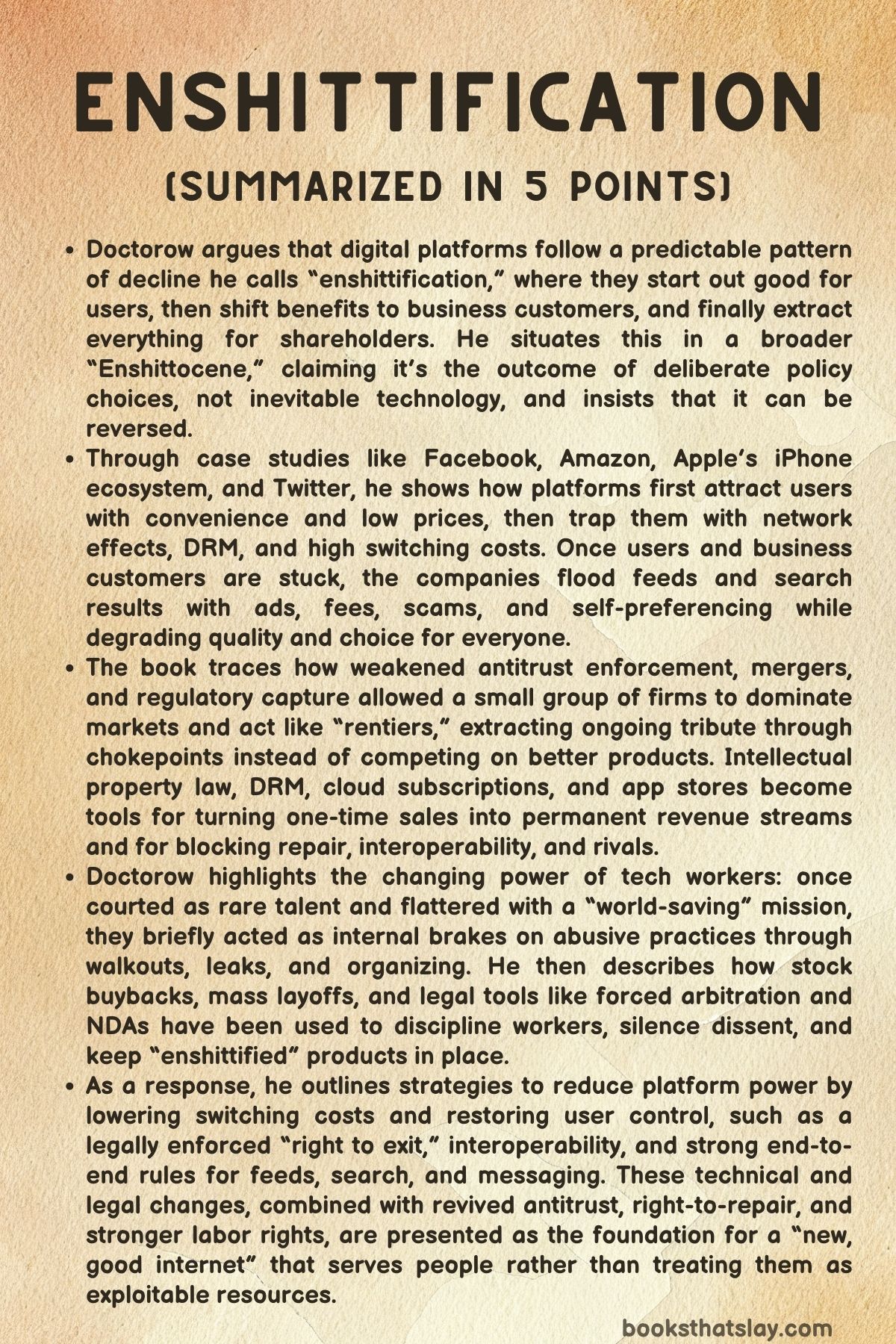

Instead, they follow a predictable pattern: at first they treat users well, then they turn toward business customers, and finally they sacrifice both to squeeze out every last cent for shareholders. The book traces how law, monopoly power, and design choices let this happen, and sets out concrete ideas for building a new, healthier digital ecosystem.

Summary

Enshittification starts from a simple observation: the internet and the devices tied to it feel worse every year. Doctorow gives that decay a name, “enshittification,” and argues that it follows a recognizable life cycle.

First, platforms shower users with benefits to draw them in. Next, they begin to favor business customers such as advertisers and merchants, quietly shifting value away from ordinary users.

Finally, they abuse both sides of the market to capture as much value as possible for themselves, leaving behind a service that barely functions but is hard to escape.

Platforms, he explains, are intermediaries connecting at least two groups: buyers and sellers, drivers and riders, friends and audiences. Early internet idealists hoped that digital tools would remove middlemen entirely so creators and consumers could deal directly.

Instead, mergers and lax antitrust enforcement produced a few mega-intermediaries like Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Google, plus new gatekeepers such as Uber and app stores. Rather than a world of many small, competitive middlemen, we got a handful of giants that were free to abuse their power.

The book moves through detailed case studies. Facebook begins as a clean, ad-free social network for students, encouraging people to build rich social graphs.

Switching costs grow as users invest their lives in the platform and drag their communities along. Once people are locked in, Facebook fills the feed with surveillance-based ads, deprioritizes genuine posts, and pressures publishers to give it their content for free while paying to reach their own audiences.

The result is a fragile system where everyone is dependent on Facebook’s opaque rules and sudden strategy shifts, even as the experience gets steadily worse.

Amazon follows a similar pattern. It starts by spending investor cash to make online shopping astonishingly convenient and cheap.

Prime, Kindle DRM, and a sprawling logistics network make it hard for customers and sellers to leave. With rivals weakened, Amazon turns on its merchants, using their sales data to clone winning products, burying competitors in search results, and layering fee after fee on sellers who must pay to remain visible and Prime-eligible.

Search pages fill up with ads, scammy products, and fake reviews. Both buyers and sellers are stuck paying what Doctorow calls an “Amazon tax” because they cannot easily go elsewhere together.

Apple’s iPhone story shows how a polished experience can turn into a control scheme. The early iPhone “just works,” and the App Store feels like a safe, curated marketplace.

Over time, Apple’s strict rules and technical locks ensure that apps, media, and even payment flows are channeled through its systems. Developers are lured with favorable terms, then hit with a 30 percent cut on transactions and banned from telling users about cheaper options off-platform.

Apple markets itself as privacy focused, yet quietly runs its own surveillance-based ad systems and selectively favors its own services over rivals.

Twitter (now X) is presented as an accelerated, chaotic version of the same story under a single, impulsive owner. Doctorow describes how, after Elon Musk’s takeover, moderation collapse, paid verification, API lockouts, and erratic policy changes made the site far worse, yet many users stayed because their communities were trapped there.

This shows how enshittified platforms can continue as “zombies,” animated by the mutual dependence of users, creators, and businesses who cannot coordinate a mass departure.

The book then widens its lens. Enshittification is not just about bad decisions inside individual firms; it is about the erosion of external checks.

For a time, tech workers themselves were a kind of constraint. Scarce skills, loose labor markets, and noncompete bans in places like California gave them unusual freedom to quit or resist when companies crossed ethical lines.

Firms responded by building a culture of “vocational awe,” telling employees they were on a heroic mission rather than simply doing a job. When that myth broke, especially as workers were asked to degrade products or support surveillance and military contracts, some pushed back.

Google becomes a major example of this internal conflict. Workers revolt over Project Maven, a military AI project, and over the handling of sexual misconduct by senior executives such as Andy Rubin.

Large walkouts win an end to forced arbitration in some cases, but management later cracks down on critics like Timnit Gebru, whose research highlighted the dangers of large language models. Meanwhile, the company spends tens of billions on stock buybacks and still lays off thousands, using fear to discipline remaining staff.

Doctorow connects this behavior to a broader shift from profit earned by production toward “rent” extracted from owning chokepoints.

That idea, drawn from Yanis Varoufakis’s “technofeudalism,” frames tech giants as lords of digital fiefdoms. Amazon controls access to customers; Apple and Google control app stores and mobile ecosystems; Uber controls rider–driver matching; ad platforms can raise prices or quietly worsen results.

These firms do not just compete; they charge admission and skim from all activity within their domain. Intellectual property law adds more arrows to their quiver: excessive patents, aggressive copyright claims, and anti-circumvention rules allow trolls and incumbents to threaten anyone who tries to build alternatives or fix problems.

Doctorow shows how cloud services amplify this power. Adobe’s shift to Creative Cloud lets it change terms and features on the fly, even threatening access to colors in old design files when Pantone licensing changes.

Unity, after becoming a dominant game engine, suddenly introduces a new per-install fee that would retroactively reshape developers’ economics. Massive backlash forces partial retreats, but the episode illustrates how centralized control enables sudden, one-sided rule changes.

Another major theme is how app-mediated work makes old-style labor abuse look new and high-tech. Gig platforms claim to be neutral “marketplaces” rather than employers, while their algorithms tightly manage pricing, routing, and ratings.

Examples like Uber’s wage-setting, Amazon’s hyper-monitored delivery drivers, outsourced call centers, and TikTok’s secret boosting of chosen content show how much power sits in software that is shielded from traditional regulatory categories.

After mapping the problem, Enshittification turns to ways out. Doctorow argues that instead of begging platforms to be nicer, we should make them less important.

Key tools include reducing switching costs, restoring competition, and giving users and workers real power over their tools and data. The fediverse, especially Mastodon, is presented as a working demonstration: users can move between servers while carrying their followers, follows, and blocks, and servers can cut ties with abusive communities.

From this example, he sketches a “right to exit,” where large platforms would be required to interoperate with rivals and provide standardized export files so people and communities can move without losing their networks.

He extends the “end-to-end” principle from network design to platform behavior. Services should faithfully carry what users request: a feed that actually shows posts from accounts you follow, search results that show the thing you asked for before ads and knockoffs, email that delivers messages you rescued from spam.

Deviations from this are not clever optimization but deceptive practice, and regulators could test for them with simple, repeatable checks.

Interoperability and a real right to repair are central. Doctorow lists examples of devices and services that become useless or hostile when a vendor flips a switch: printers that reject third-party ink, smart devices bricked by bad updates, even medical implants abandoned by bankrupt companies.

Laws like DMCA 1201, which criminalize bypassing digital locks, make it nearly impossible for independent repair shops, accessibility experts, or rival developers to legally build tools that keep products and services useful. Triennial exemptions help on paper but fail in practice because people are barred from sharing circumvention tools.

The book closes by tying together antitrust revival, interoperability campaigns, right-to-repair laws, labor organizing, and privacy struggles into a single project: building a “new, good internet.” Enshittification is not a natural law. It is the outcome of policy choices that strengthened monopolies, weakened regulators, banned self-help, and kept workers and users isolated.

By reversing those choices and insisting on competition, user mobility, and collective power, Doctorow argues that we can turn the same digital infrastructure that currently extracts from us into something that serves us instead.

Key People and Companies

Cory Doctorow

Cory Doctorow appears in Enshittification as both narrator and central moral presence, a guide who threads together anecdotes, case studies, and legal history into a unified indictment of the current digital order. He is not a detached academic; his voice is that of a participant-observer who remembers the “old, good internet” and feels personally betrayed by how it has been captured and degraded.

Throughout the book, Doctorow positions himself as someone who understands both technical architecture and political economy, constantly translating between the two. He insists that enshittification is not an accident or the inevitable outcome of “technology,” but the consequence of specific choices by identifiable people under a particular legal and economic regime.

This insistence reflects his character as a political storyteller: he wants the reader to feel that villains, victims, and possible heroes are all real and nameable, not abstractions.

Doctorow also functions as a kind of organizer-in-print. He repeatedly points away from resignation and toward coordinated action: worker organizing, regulatory reform, interoperability campaigns, and right-to-repair activism.

His character is defined by a refusal to accept the narrative that the internet’s collapse into surveillance and lock-in is natural or irreversible. Instead, he ties together scattered fights—antitrust, privacy, labor, repair, interoperability—into one story, hoping to give readers the same sense of unity that “ecology” once gave to disparate environmental struggles.

His role is to make the enshittified status quo feel neither inevitable nor apolitical, but contingent and therefore changeable.

Users and Communities

Users and communities in Enshittification are the primary victims of the platforms’ transformation, but they are also a latent source of power. Doctorow stresses how deeply people’s lives are interwoven with digital services: social ties, professional networks, mutual aid groups, fandoms, and family relationships all live on platforms.

This dependence is what makes “switching costs” so painful. Leaving Facebook, Twitter, or Amazon is not a simple consumer choice; it means losing easy access to friends, customers, colleagues, and support networks.

As enshittification advances, users are systematically downgraded from valued participants to exploited resources, their attention and data treated as raw material to be mined, sliced, and resold.

Yet the book also treats users as potential agents of change, especially when they act collectively. The example of Mastodon and the fediverse shows users and communities reclaiming some control by choosing different moderation regimes, migrating together between servers, and punishing abusive hosts through “defederation.” Doctorow’s proposed “right to exit” assumes that users, if freed from lock-in, will sometimes coordinate to leave exploitative platforms en masse, reshaping markets by their choices.

In this role, users resemble a sleeping giant: individually vulnerable and easy to manipulate, but collectively capable of turning enshittified giants into “zombie” platforms, sustained only by desperation until an exit route appears.

Tech Workers

Tech workers form one of the most complex collective characters in Enshittification. At first, they appear as beneficiaries of the tech boom, enjoying high salaries, lavish perks, and cultural prestige.

Their employers cultivate “vocational awe,” persuading them that they are not mere workers but heroic builders of the future, destined to become founders themselves. This ideology encourages them to accept brutal working hours and to overlook the growing harms of the products they build.

The companies’ strategy works for a while: instead of discipline via unions and clear labor rules, management governs through campus-like comfort and a sense of mission.

However, these same workers become a crucial internal check on enshittification when they feel that mission is being betrayed. At Google, revolts over Project Maven and the Andy Rubin scandal show tech workers suddenly discovering their capacity for collective action: organizing walkouts, leaking documents, and forcing management to abandon lucrative projects and change policies like forced arbitration for sexual misconduct.

In these moments they are a countervailing force against surveillance capitalism and militarization. Over time, though, mass layoffs, shrinking job mobility, and management’s growing intolerance for dissent (as in the firing of Timnit Gebru) erode this power.

Tech workers are transformed from autonomous artisans in high demand into more precarious employees who are expected to help enshittify products and accept it silently. They embody both the hope that insiders can resist and the danger of relying on elite conscience instead of formal worker power like unions.

Platform Owners and Shareholders

Platform owners and shareholders are the primary villains in Enshittification, even when individual names are only occasionally mentioned. They are characterized not by personal quirks but by a structural role: they are the group to whom all surplus is ultimately redirected as platforms move through Doctorow’s stages of decline.

In the early phase, they are willing to subsidize low prices, generous terms, and user-friendly features with investor money, treating losses as an investment in dominance. Once a platform has locked in users and business customers, these same owners demand that every possible margin be squeezed for profit.

This character becomes particularly stark in the discussion of stock buybacks, dividends, and mass layoffs. The decision to spend tens of billions on buybacks while firing thousands of workers is framed as a pure expression of shareholder supremacy: value is measured strictly by share price, not by the quality of services, the well-being of workers, or the health of the information ecosystem.

Owners push managers to treat platforms as “chokepoints” for rent extraction rather than as tools for solving problems. In this sense, platform owners and shareholders are the true protagonists of the Enshittocene, the ones whose expectations and incentives shape everything from spyware in phones to wage discrimination in gig work.

Facebook in Enshittification is a paradigmatic enshittified platform, a character that moves clearly through Doctorow’s three stages. It begins as a clean, appealing social network that really is “good to users”: a college-only space where people can build their social graph, see their friends’ posts chronologically, and enjoy the thrill of connection.

Facebook promises privacy and even offers tools to help users migrate from MySpace, framing itself as a friendlier alternative to the messier old platform. At this stage, Facebook’s character is that of an eager suitor, bearing gifts in the form of features and protections.

Once network effects and social lock-in entrench Facebook, its character shifts from suitor to exploiter. Users become the product; their attention and data are sold to advertisers and publishers, while algorithmic manipulation of the feed maximizes “engagement” at the cost of user intent.

Gradually, Facebook turns on business customers as well, charging more for reach, forcing publishers to post directly on its platform, and suppressing external links. The feed becomes crowded with ads, boosted posts, and clickbait, while users’ own chosen content is buried.

The company’s arc culminates in a kind of madness, exemplified by its Metaverse pivot: having enshittified its core product, it thrashes desperately for a new growth story. Facebook’s final characterization is that of a zombie monopoly—no longer beloved, often hated, but still difficult to escape because of the switching costs embedded in everyone’s social lives.

Amazon

Amazon is portrayed as a master of the bait-and-switch, a platform that moves from consumer champion to predatory landlord. At first, its character is almost heroic from a shopper’s perspective: low prices, fast and cheap shipping, generous return policies, and an ever-expanding catalog.

Investor cash subsidizes this generosity, while Amazon’s rhetoric celebrates efficiency and innovation. Prime memberships, one-click shopping, and a growing ecosystem of devices and services deepen the bond, making Amazon feel like a trustworthy default for everything.

Behind the scenes, however, Amazon is steadily reshaping markets to create dependence. Diapers.com is the most vivid example: Amazon is willing to burn $200 million selling diapers below cost to crush a rival, then buys and shuts it down.

For merchants, Amazon shifts from partner to overlord, using its privileged access to sales and supplier data to clone best-selling products, bury originals in search results, and load merchants with a tangle of fees. Over time, the character of Amazon’s search page changes: from a neutral directory of the best products to a pay-to-play battlefield crammed with sponsored results, low-quality clones, and manipulated reviews.

By the time the platform is fully enshittified, both shoppers and merchants feel trapped, paying an “Amazon tax” either in direct fees or in higher prices everywhere else. Amazon’s character becomes that of a tollbooth operator standing astride the digital mall.

Apple and the iPhone Ecosystem

Apple in Enshittification is a more ambiguous character, initially cast as the “good” alternative to surveillance-heavy, fragmented systems. The iPhone launches as a polished, cohesive ecosystem that “just works,” with a curated App Store that seems to protect users from malware and the chaos of unvetted apps.

Compared to Android’s wild west, Apple’s walled garden looks safe and dignified, promising privacy and quality. Users who enter this garden come to depend on its reliability, elegant design, and integrated services.

Over time, the walled garden becomes a trap. Apple’s control over the App Store, operating system, and DRM-locked media gives it immense leverage over both users and developers.

The book depicts Apple as selectively hypocritical about privacy: it quietly tolerates invasive tracking by big players like Facebook while preventing users from installing their own privacy defenses. Later, when it introduces a simple tracking opt-out that devastates third-party ad businesses, Apple simultaneously builds its own surveillance-based ad system, replacing rather than eliminating tracking.

Meanwhile, the company ratchets up its “tax” on developers, enforcing a 30 percent cut, banning steering to cheaper payment options, and exempting its own services. Independent firms cannot survive under these terms, while Apple’s own offerings receive favorable treatment.

The character of Apple thus shifts from benevolent curator to self-dealing gatekeeper, wielding user trust and platform control to extract rents under the banner of privacy and quality.

Twitter appears as a tragic figure that accelerates through the stages of enshittification in fast motion, particularly after Elon Musk’s takeover. Initially, Twitter is a quirky, open platform defined by its users’ creativity and the openness of its APIs.

Third-party clients, bots, and tools are not parasites but first-class citizens, and the company is famous for “paving desire paths” by incorporating user-invented practices like retweets and quote tweets. Twitter’s early character is that of a messy, improvisational commons where innovation comes from the edges.

As time passes, pre-Musk Twitter compromises on moderation and state pressure, but the real lurch into enshittification comes under Musk. The new owner, burdened with debt, slashes moderation staff, which floods feeds with scams and gore, and alienates advertisers.

Verification, once a signal of authenticity, is turned into a paid status symbol, then degraded into a badge of trolls and spammers. Unpaid accounts are suppressed, rival platforms are censored, and the API is strangled to prevent users from using tools that help them migrate elsewhere.

Twitter’s character morphs into that of an insecure tyrant, obsessed with forcing users to stay while stripping away everything that made the place livable. Yet even in this degraded state, people remain, because their social graphs and professional communities are still there.

Twitter becomes the archetypal “zombie platform”: visibly decayed, but animated by the inability of its user base to coordinate an exit.

Google’s Management and Corporate Culture

Google in Enshittification is portrayed as a company with a split personality. On one hand, it is the innovator that created world-class search and attracted brilliant engineers behind a “Don’t be evil” ethos.

On the other hand, it is a serial acquirer that buys success (Android, YouTube, Maps, Docs) and uses its dominance and default status to avoid meaningful competition. The internal documents revealed in antitrust cases show executives deliberately considering how to make search worse—such as forcing users into more queries to see more ads—undermining the myth that Google’s products are shaped only by user experience and technical excellence.

The book’s depiction of scandals like Project Maven, the Andy Rubin case, and Timnit Gebru’s firing reveal a leadership increasingly focused on stock price and political positioning rather than ethical commitments. The worker revolts show Google’s culture fraying, as employees who believed in the “Don’t be evil” brand learn that it is more slogan than principle.

When Google introduces dividends and a massive buyback just before cutting tens of thousands of jobs, its character definitively shifts from idealistic engineering shop to classic rent-extracting corporation. Google’s leaders become emblematic of how a company can weaponize a once-good product and a once-inspiring culture in service of financial engineering and monopoly preservation.

Microsoft

Microsoft appears as a long-running antagonist whose arc illustrates the ebb and flow of antitrust enforcement. Its early history, shaped by the IBM and DOJ cases, is a cautionary tale of how strong regulation can both restrain a monopolist and open space for new players like Google.

For a time, Microsoft seems chastened, pulling back from some aggressive tactics as it navigates legal scrutiny. This generates a sense that antitrust can work, that giants can be forced to behave.

But as institutional memory of those battles fades, Microsoft reverts to enshittifying behavior, especially as it migrates Office to the cloud via Office365. Cloud control allows Microsoft to change features, pricing, and interoperability on a whim, nudging or forcing users toward its preferred ecosystem and harvesting granular data on workplace behavior.

In the book’s narrative, Microsoft’s character is that of an old monopolist that learned just enough from past punishments to hide its claws for a while, then grows bolder as regulators go to sleep. Its story supports Doctorow’s broader claim that monopolies are not stable solutions; they are recurring problems that must be confronted again and again.

Adobe

Adobe in Enshittification is a tightly written example of how software companies use subscriptions and DRM to turn tools into perpetual rent streams. In its earlier days, Adobe’s Creative Suite is a one-time purchase: expensive, but owned.

With Creative Cloud, Adobe transitions to subscription-only access, transforming every designer’s workflow into a recurring revenue stream. The company’s character shifts from toolmaker to gatekeeper, controlling access not only to new versions but to the user’s own historical work.

The Pantone incident demonstrates the cruelty of this model. By allowing Pantone to effectively “ransom” access to colors embedded in old files, Adobe is portrayed as willing to hold users’ past creations hostage to third-party licensing deals.

Later, the attempt to quietly force users to accept terms that allow Adobe to use their work to train AI intensifies this depiction. The backlash that forces Adobe to retreat shows that users still have some power, but only when outrage is highly visible.

Adobe’s character thus becomes that of a company that treats creative labor not as something to enable but as a vein to mine over and over, using software control, DRM, and legal fine print to keep the vein open.

Unity

Unity serves as a dramatic case study in how enshittification can backfire when a company oversteps. Initially, Unity is a beloved game engine, lowering the barrier to entry for small developers and enabling a flourishing indie ecosystem.

Its business model seems aligned with creators’ interests: affordable tools, flexible licensing, and a sense that the company and its users are building something together. Unity’s character is that of an ally, the friend of the small studio.

The sudden imposition of a retroactive “runtime fee” on every install of Unity-built games shatters this trust. By changing the terms after developers have committed to long, expensive projects, Unity effectively announces that it sees those projects as hostages.

The industry’s furious response—public revolts, halted development, mass denunciations—is a rare example where enshittification sparks immediate, organized resistance. Leadership changes and a crushed stock price follow, though parts of the scheme remain.

Unity emerges as a cautionary character: a firm that mistook developers’ dependence for consent, and learned that some forms of rent extraction are so blatant that they can galvanize a counter-movement.

Uber and App-Based Gig Platforms

Uber and similar app-based gig platforms appear as archetypal “doing crime with an app” characters. They present themselves as mere intermediaries, digital marketplaces connecting drivers and riders, and thus claim exemption from labor laws, employer obligations, and regulatory frameworks built for traditional firms.

The book shows how this convenient fiction allows them to impose forms of control that would, in any other context, clearly mark them as employers: algorithmic wage-setting, opaque penalties, dynamic deactivation, performance surveillance, and constant metrics-based pressure.

The concept of “algorithmic wage discrimination” highlights how these platforms exploit their data to pay different people different amounts for similar work, making wages unpredictable and undermining worker solidarity. Uber’s character in the narrative is that of a cunning outlaw aristocrat, hiding behind code and “innovation” rhetoric while evading rules that protect workers and cities.

When paired with examples like Amazon’s hyper-monitored delivery drivers and the “pee bottle” scandal, Uber becomes part of a broader class of platforms that shift risk onto workers, demand total obedience, and then insist in court that those workers are independent entrepreneurs.

Regulators and Antitrust Enforcers

Regulators and antitrust enforcers in Enshittification are complicated supporting characters: sometimes heroic, sometimes absent, often constrained by courts and political shifts. Figures like Lina Khan at the FTC, Jonathan Kanter at the DOJ, and agencies such as the CFPB or the UK’s Digital Markets Unit are portrayed as a new generation trying to revive dormant tools and adapt them to platform capitalism.

Their efforts to challenge mergers, design interoperability rules, and penalize deceptive practices represent a partial revival of the state’s ability to constrain corporate power.

At the same time, courts and politicians, especially in moments of deregulatory or authoritarian ascendancy, are shown undermining these regulators. Decisions that gut doctrines like Chevron deference and political interventions that fire or sideline key enforcers reduce the administrative state’s capacity to act.

The book portrays Trump and his allies as eager to stall or reverse regulatory efforts while indulging in culture-war distractions. Regulators thus appear as embattled protagonists in a hostile environment, often outgunned by well-funded corporations and hostile legal doctrines, but still crucial to any path out of the Enshittocene.

Yanis Varoufakis and the Concept of Technofeudalism

Yanis Varoufakis appears less as a character in his own right and more as a representative of a theoretical lens: technofeudalism. In Enshittification, his work is used to articulate the shift from profit, earned by investing in production, to rent, extracted simply by owning and controlling chokepoints in the digital economy.

Varoufakis’s idea helps Doctorow frame platforms not just as big companies but as a new kind of feudal lord, charging access fees to markets, audiences, and infrastructure.

By invoking Varoufakis, the book signals that it is part of a broader intellectual conversation about the nature of contemporary capitalism. Technofeudalism gives a name to the intuition that being a merchant on Amazon or a creator on TikTok feels less like a business partnership and more like tenancy on someone else’s land.

Varoufakis’s role, therefore, is to provide vocabulary and conceptual clarity that turns scattered grievances into a coherent diagnosis, reinforcing Doctorow’s argument that the core problem is rent extraction via control of chokepoints.

Intellectual Property Enforcers and Trolls

Patent trolls, copyright trolls, and copyleft trolls appear in Enshittification as a swarm of parasitic minor villains who nonetheless wield significant power. They rarely produce anything themselves; their business is to weaponize overbroad intellectual property laws and technical license conditions to extract settlements from productive firms and individuals.

Creative Commons images turned into traps through tiny attribution gotchas, or mass-produced works designed to generate lawsuits, exemplify how something originally meant to encourage sharing can be twisted into a business model of legal ambush.

These trolls are the foot soldiers of technofeudalism, exploiting laws drafted and expanded under pressure from large corporate rightsholders. Their existence underscores a core theme of the book: rules written to protect “property” in the abstract can, in practice, become tools to punish creativity, experimentation, and small-scale production.

As characters, they represent the absurdity and cruelty of a legal order that treats accidental license violations as opportunities for extraction, while allowing large platforms to abuse users with relative impunity.

Interoperability and Right-to-Repair Activists

Interoperability advocates, right-to-repair organizers, and the builders of the fediverse occupy the role of underdog heroes in Enshittification. They are the people who refuse to accept that devices must be bricked when a company folds, that printers must reject third-party ink, or that smart home gear must die when a vendor turns off a server.

They often work in small organizations, local politics, or specialized domains like agricultural equipment or medical devices, but their efforts share a common goal: restoring user control by enabling alternative software, parts, and services.

These activists are central to the idea of adversarial interoperability, the practice of building tools that plug into, route around, or replace enshittified systems without the platform’s permission. In a world where DMCA-style anti-circumvention laws criminalize reverse engineering and tool-sharing, their work is risky, but it is also presented as essential.

They embody the possibility of a “new, good internet” in which users are not trapped in proprietary silos but can exit, modify, and repair. As characters, they are stubborn, technical, and politically savvy, using small legal openings—like state-level right-to-repair laws—to chip away at global regimes that protect corporate choke points.

Themes

The Lifecycle of Enshittification and Platform Decay

Doctorow presents enshittification as a predictable, staged process rather than a random decline in quality, and Enshittification keeps returning to the same structural pattern: platforms first court users, then business customers, and finally strip-mine both to enrich shareholders. Early on, platforms appear almost altruistic.

Facebook offers a clean feed of friends’ posts and tools to coordinate social life; Amazon burns investor cash to subsidize low prices and convenient delivery; Apple’s iPhone seems like a safe, polished refuge from malware and chaotic ecosystems. These early phases are not accidents or expressions of corporate benevolence; they are investments.

The platform is spending money and foregoing profit to build a user base, construct switching costs, and create expectations that life, work, and community run through its infrastructure.

Once the user base is locked in, the balance shifts toward business customers. Advertisers and merchants are initially treated well: honest rankings, reasonable rates, clear rules.

Publishers get traffic from Facebook, small merchants gain a national audience through Amazon, developers flock to the App Store with the promise of fair revenue shares. But as the platform’s dominance grows, it begins modifying the rules in ways that capture more of the surplus it once shared.

Organic reach is throttled unless publishers pay. Amazon pushes sponsored results and clones successful products.

Apple raises its take on transactions and bans cheaper payment routes. Eventually, even business customers are no longer partners but hostages, facing rising fees, degraded visibility, and arbitrary enforcement.

The end state is a “zombie” service: users stay because their social graph, data, and livelihoods are stuck there; businesses stay because there is nowhere comparable to go; the platform is visibly worse for everyone, but the costs of leaving are higher than the misery of staying. Enshittification in this sense is not a moral failing or “tech gone wrong” story but a logical consequence of power accumulating inside closed two-sided markets whose owners face few external constraints.

Monopoly, Concentration, and Rentier Capitalism

Across the case studies, Enshittification treats monopoly not as a backdrop but as the engine that allows enshittification to run to completion. Doctorow argues that the transformation from competitive markets to concentrated “chokepoints” is enabled by a long political project: weakening antitrust enforcement, tolerating predatory pricing, and measuring harm only through short-term consumer prices.

Amazon’s war on Diapers.com is presented as a textbook example of how a firm with deep capital reserves can sell below cost to eliminate a rival, absorb its assets, and then quietly shut it down. This is not clever entrepreneurship; it’s the exercise of a war chest to buy a market, betting that regulators will look away as long as prices are temporarily low.

Over time, these tactics yield industries dominated by a few giants who can behave less like businesses and more like landlords. The book draws on Varoufakis’s “technofeudalism” to describe how platforms shift from earning profits by producing and improving things to extracting rent simply by owning bottlenecks.

They charge for access, visibility, and participation: Amazon takes a cut from nearly every dollar a merchant earns on the platform; Apple and Google skim up to 30% of app revenue; Uber controls access to riders; Facebook and Google control access to audiences. These actors become both monopoly sellers to users and monopsony buyers from workers and suppliers, squeezing both sides.

Even when firms continue to innovate in small ways, their most reliable income comes from controlling the rails that others must use. Stock buybacks and dividends at firms like Google become symptoms of this transition: instead of reinvesting in products or staff, surplus is used to boost share price and reward investors.

Enshittification thus appears as the cultural and experiential face of a deeper economic shift, where concentrated power and lax oversight transform digital infrastructure into rent-extracting estates.

Lock-In, Switching Costs, and User Autonomy

The book repeatedly shows that enshittification only “works” because users and business customers cannot easily leave. Network effects, data silos, DRM, proprietary formats, and contractual restraints all contribute to a landscape where the decision to walk away is punishingly expensive.

Facebook’s early promise not to spy, or Apple’s promise that the iPhone “just works,” matter less than the fact that, once established, these systems become the default location for friendships, work collaboration, community organizing, and even access to customers. Leaving Facebook means losing contact with groups, events, and networks.

Leaving Amazon as a merchant means abandoning the place where most customers start their search. Leaving Apple’s ecosystem means abandoning purchased apps, DRM-locked media, and tightly integrated services.

Doctorow is particularly interested in switching costs as a policy lever. When users lack a “right to exit,” platforms can tighten the screws indefinitely, confident that complaints will not translate into mass departures.

That is why the fediverse and ActivityPub loom so large in Enshittification: they offer a living demonstration that migration can be almost painless if the system is designed for it. On Mastodon, a user can move from one server to another, carrying followers, follows, and blocks in a simple export–import step.

Servers can cut ties with abusive instances, and communities can relocate together when governance fails. This stands as an existence proof that social graphs need not be prison walls.

Doctorow’s proposal to legally mandate such interoperability for dominant platforms reframes autonomy as a structural condition, not a matter of individual willpower. If Twitter or Facebook had to provide a standardized file that any compatible service could import, the fear of losing one’s network would diminish, and platforms would face a constant competitive threat from outside services that promise better moderation, better economics, or better governance.

Lock-in is therefore not just a technical detail but a central theme: it is the hidden infrastructure that converts dissatisfaction into resignation, making enshittification sustainable even when everyone can see that things are getting worse.

Surveillance, Data Extraction, and Algorithmic Control

Surveillance in Enshittification is not treated as a side effect of advertising but as a core tool for extraction and control. Platforms gather data to target ads more precisely, but also to manipulate the behavior of users, workers, and business partners.

Facebook’s slow transformation from a chronological feed into a pay-to-play attention marketplace depends on continuous measurement and profiling. Google’s ad systems use search terms, browsing data, and complex auction manipulations like “semantic matching” to show more ads, charge more for them, and obscure what is actually happening from both advertisers and users.

Apple’s trajectory from privacy-forward branding to running its own data-fueled ad network illustrates how “privacy” itself can become a competitive weapon: by crippling third-party tracking while maintaining privileged access for its own systems, Apple converts the moral high ground into a strategic moat.

The same logic extends beyond consumer-facing interfaces into the working lives of people whose labor is mediated by apps. Uber’s “algorithmic wage discrimination” depends on collecting vast amounts of data on driver behavior, location, and acceptance patterns, then using that information to customize offers and subtly reduce bargaining power.

Amazon’s logistics empire monitors drivers to absurd degrees, down to bathroom breaks, using data dashboards to justify punishing quotas and automated discipline. TikTok’s hidden “heating” tool allows staff to push particular videos into virality, sustaining the illusion of a neutral recommendation algorithm while quietly rewarding or punishing creators for strategic reasons.

In each case, the platform uses its data advantage to rewrite the terms of participation after participants have already become dependent. Surveillance thus underpins both economic enshittification (by enabling ever more granular price discrimination and rent extraction) and political enshittification (by letting firms design attention architectures that favor their interests over users’ autonomy).

Doctorow’s concern is not only privacy in the narrow sense, but the way asymmetries of knowledge create asymmetries of power, turning both consumers and workers into experimental subjects in systems they do not control and barely understand.

Labor, Vocational Awe, and the Crushing of Worker Power

One of the striking threads in Enshittification is its depiction of tech workers as both beneficiaries and eventual casualties of enshittification. Early on, the scarcity of their skills and the absence of noncompete enforcement in places like California give them unusual bargaining power.

Instead of traditional factory-floor discipline, employers cultivate “vocational awe”: the belief that building apps or platforms is a noble mission, not just a job. Lavish perks, playful campuses, and slogans about changing the world encourage engineers to work extreme hours and internalize corporate goals as personal ethics.

For a time, this arrangement produces a workforce that identifies strongly with products and users, and occasionally pushes back when management demands harmful changes. The revolt over Google’s Project Maven and the walkouts over Andy Rubin’s payout show staff using their labor market strength and moral authority to contest decisions about surveillance, military work, and sexual abuse cover-ups.

But as the book progresses, this fragile check on corporate excess is systematically eroded. Binding arbitration clauses and NDAs strip workers of legal recourse and silence; Supreme Court decisions extend these tools into nearly every employment relationship.

Unionization efforts meet sophisticated resistance. Most dramatically, mass layoffs at profitable firms send a clear message: loyalty and performance offer no protection, and management is willing to fire thousands simply to reassure investors and discipline those who remain.

Google’s choice to spend tens of billions on buybacks and then shed tens of thousands of employees symbolizes this shift from investing in people and products to treating staff as a variable cost and stock price as the true product. Internal critics like Timnit Gebru, who challenge the ethics and risks of large language models, are sidelined or expelled, shrinking the space for conscience within the firm.

Vocational awe curdles into disillusionment as workers realize that the “world-changing” mission can be flipped overnight into a justification for abusive business models, surveillance products, or military contracts. In the end, worker power appears as another constraint that was temporarily present, briefly effective, and then deliberately undermined to clear the path for full enshittification.

Law, Intellectual Property, and Regulatory Capture

Doctorow shows that the legal environment is not a neutral backdrop but an active participant in enshittification. Over decades, antitrust enforcement is narrowed to a single question—are prices lower today?—which leaves regulators blind to harms involving quality, innovation, privacy, and worker exploitation.

This myopia allows dominant platforms to grow through mergers, exclusive contracts, and predatory tactics with little fear of challenge. When regulators finally stir, as in the DOJ’s case against Google search defaults, they uncover internal documents that confirm deliberate strategies to worsen experiences for users in order to increase ad impressions.

Yet these cases are exceptions in a broader landscape where firms shape the rules as much as they obey them.

Intellectual property law, particularly anti-circumvention measures like DMCA Section 1201 and their international clones, becomes a key legal tool for maintaining chokepoints. By criminalizing the act of bypassing digital locks even for lawful purposes, these statutes give companies the power to prevent repair, block interoperability, and suppress competing services that would help users escape enshittified ecosystems.

The absurdity of exemptions that allow an individual blind person to crack their own software, but forbid anyone from sharing tools with them, underscores how the system is designed to preserve corporate control, not public interest. Parallel abuses by patent trolls, copyright trolls, and bad-faith actors exploiting Creative Commons licenses reveal how IP frameworks are weaponized to extract settlements from productive firms and small creators.

At the same time, regulatory agencies are whipsawed by political cycles: moments of renewed antitrust ambition under figures like Lina Khan and Jonathan Kanter are followed by court decisions that strip agencies of interpretive authority and administrations that redirect them into culture-war theater. The result is a patchwork of partial victories and sweeping defeats, in which tech giants can usually count on weak oversight and fragmented enforcement.

Regulatory capture is not just lobbyists whispering in lawmakers’ ears; it is the overall drift of law toward protecting capitalized chokepoints and criminalizing the tools that citizens might use to resist them.

Interoperability, Right to Repair, and the Struggle for a New Internet

Despite its bleak catalog of abuses, Enshittification is ultimately organized around the possibility of reversing the trend by restoring interoperability, repair, and genuine exit rights. Doctorow argues that the “old, good internet” was not utopian because people were nicer, but because its architecture and legal environment prevented any single actor from totalizing control.

Open protocols, open standards, and a diversity of intermediaries gave users choices and made it easier for innovators to build on top of existing systems. The challenge, then, is not to return nostalgically to that era, but to design a “new, good internet” that preserves modern usability while reintroducing competition and user self-defense.

Key to this vision are concrete mechanisms such as the right to exit, end-to-end obligations, and right to repair. A legal requirement that dominant platforms provide standardized, machine-readable export files—and federate with rivals where appropriate—would let communities relocate together without losing their networks.

End-to-end rules for social feeds, email, and search would give users at least one honest channel free of pay-to-play manipulation, making deceptive ranking and throttling practices legally risky. Right-to-repair and anti-DRM campaigns, especially in focused domains like cars, wheelchairs, and consumer electronics, would pry open hardware so that independent shops and developers can keep devices functioning and compatible even after manufacturers abandon them.

These interventions are framed as mutually reinforcing: interoperability and repair lower switching costs; lower switching costs revive competition; revived competition punishes enshittification. Doctorow stresses that none of this happens automatically.

It requires organizing by workers, consumers, and citizens, along with regulators who choose administrable, testable rules rather than vague mandates. The closing argument is that enshittification is a political outcome, not a law of nature, and that the same digital tools currently used to surveil and manipulate can be repurposed to coordinate resistance, build alternatives like the fediverse, and push governments toward policies that favor open systems over chokepoints.