One Killer Night Summary, Characters and Themes

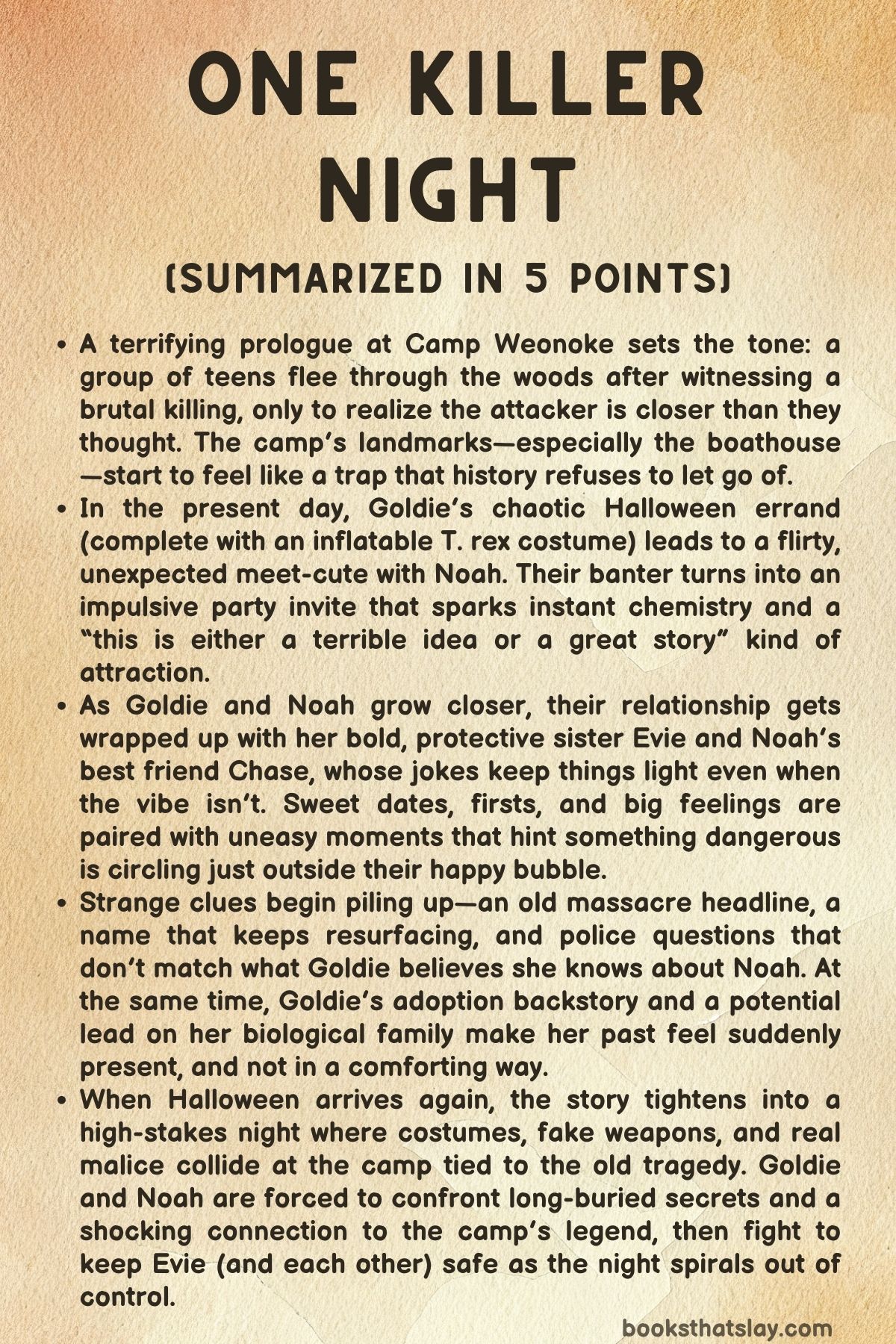

One Killer Night by Trilina Pucci is a romantic thriller that fuses modern-day charm with chilling suspense. It follows Goldie, a quirky and lovable woman who meets the mysterious Noah on Halloween night.

What begins as a lighthearted, funny encounter quickly spirals into something darker as their budding romance unearths secrets buried for decades. With a mix of humor, heat, and horror, the story explores identity, love, and inherited violence. Pucci balances romance and terror, crafting a narrative where love can heal deep wounds but the past always leaves a shadow. The novel builds from flirtation to a full-blown nightmare that refuses to stay buried.

Summary

The book opens in a haunting prologue where a terrified girl and four boys flee through the woods after witnessing a brutal murder. Panic and confusion reign as they try to find safety, but one of them is killed before their eyes by a monstrous figure.

The killer’s chilling words—there’s no escaping him—set the stage for a story where trauma and violence echo across generations.

Years later, on Halloween night, Goldie is introduced as a warm, clumsy woman with a wicked sense of humor. She’s shopping for her sister Evie, a special effects artist, while wearing an inflatable dinosaur costume.

A chance encounter at Walgreens with an attractive stranger named Noah turns into instant chemistry. Their playful banter, full of pop-culture jokes, leads Goldie to impulsively invite him to a Halloween party at Evie’s workplace.

Noah, intrigued and amused by Goldie’s spontaneity, decides to go. He throws together a ghost costume from a bedsheet and arrives at the warehouse, where he learns the party is an elaborate horror-themed event hosted by Mass FX.

When he spots Goldie out of costume, he’s captivated. They flirt, tease each other, and end up leaving together for a quieter night out.

Riding through Boston on Noah’s motorcycle, they talk about their pasts—Goldie reveals she’s adopted, found as a baby at a police station, while Noah shares that he lost his mother and never knew his father. Their connection deepens through humor and honesty.

When Goldie sets playful “date conditions,” including stealing her candy and giving her an unforgettable kiss, Noah rises to the challenge. They end their first date with an intense, memorable kiss and decide to see each other again.

As their relationship grows, Noah’s best friend Chase brings comic relief and skepticism about Noah’s seriousness. Despite Chase’s teasing, Noah is determined to make Goldie his girlfriend.

At a dinner orchestrated by Chase, the relationship becomes official. But when a drunk man calls Noah “Davis” and references a mysterious place called Darkwater Bay, hints of Noah’s hidden past surface.

That night, a shadowy figure watches them from afar.

Their love story continues with passion and laughter, but nightmares begin to disturb Noah. He wakes one night to find a mysterious envelope containing newspaper clippings about a decades-old massacre.

Before he can make sense of it, Goldie unknowingly startles him, and he hides his discovery. His fear grows, but he tries to protect Goldie from whatever haunts him.

Months later, during a Christmas festival, Goldie, Noah, Chase, and Evie reunite for a chaotic but cheerful day. When Goldie enters a House of Mirrors, a confrontation with a harasser ends violently as Noah nearly kills the man.

His protective instinct turns into rage, leaving Goldie shaken but touched by his devotion. She reassures him of her feelings, and they reaffirm their love.

By summer, Goldie’s career begins to bloom when her writing is published in a lifestyle magazine. Her happiness is interrupted when she finds another newspaper clipping about a massacre at “Darkwater.” The story seems familiar, but she can’t recall why.

When Evie mentions birth-parent searchers contacting their father, a thread of mystery ties Goldie’s present to something much older.

Flashbacks to the past reveal the origins of that darkness. At Camp Weonoke decades earlier, a young counselor named Sonny becomes entangled with a dangerous boy named Billy, the camp’s janitor.

Their relationship turns violent when jealousy and obsession drive Billy to assault her. Sonny’s boyfriend Davis intervenes, and the boys take revenge by torturing Billy and leaving him for dead.

But Billy survives.

Back in the present, Goldie’s world begins to unravel. Chase is nearly killed in a hit-and-run involving Noah’s motorcycle, and detectives begin investigating.

They reveal there’s no record of a “Noah Adler,” making Goldie question everything she knows. Noah’s secrecy deepens the sense of foreboding.

Months later, Noah plans to propose at a surprise Halloween party that mirrors the night they met. Goldie, dressed again in her dinosaur costume, enjoys the party until she answers a call on Noah’s forgotten phone.

A police officer informs her that fingerprints found in the hit-and-run case belong to Davis Keller, not Noah Adler. The name jolts her memory—the drunk man who once called Noah “Davis.” She realizes Noah has been lying about his identity.

The story returns to Camp Weonoke, now a reopened site for a Halloween event. Goldie and Evie are there, unaware of the nightmare awaiting them.

When Goldie explores the camp, she meets Remus, a creepy manager who recounts the legend of the camp’s massacre—a boy, betrayed and tortured, returned to slaughter five counselors. The myth unsettles her, and when she’s later attacked, she discovers her assailant is Noah.

Noah pleads that she’s in danger and that he’s been trying to protect her. Goldie locks herself away until he reveals proof: a message showing the murder of a private investigator who had been helping Goldie trace her past.

Noah explains the truth—his real name is Davis Keller, and his mother was one of the survivors of the original Camp Weonoke massacre. The killer from that night, William Bromley, is his father—and still alive.

Together, they race to find Evie as chaos erupts at the camp’s party. Remus turns on Noah, and the true killer, Billy, appears.

In a shocking twist, Billy reveals that he isn’t Noah’s father—he’s Goldie’s. He proves it by showing her matching birthmark, exposing that she is the daughter of the man responsible for the Camp Weonoke killings.

The final confrontation happens at the boathouse, echoing the terror of the prologue. Billy attacks the group, stabbing and brutalizing them in the chaos.

Noah fights to save Goldie and ultimately kills Billy with his own knife. Sirens fill the air as the nightmare ends, and the survivors are rescued.

Weeks later, Noah moves to Los Angeles for work, and Goldie decides to follow him. He surprises her at her job with an elaborate floral proposal, and they marry that same day.

Eighteen months later, their love story has been turned into a film written by Goldie herself. At the movie’s private screening, everything seems perfect—until a scream breaks the peace.

Evie discovers a human heart pinned inside a bathroom stall with blood written above it: “She’s mine.” The message suggests that the terror they thought was over has only begun.

Characters

Goldie

Goldie is the heart of One Killer Night, a woman whose blend of humor, resilience, and vulnerability drives the emotional current of the story. Introduced in a comic light—fumbling through a Walgreens in an inflatable T. rex costume—she embodies both quirkiness and a hidden depth that gradually unfolds.

Her humor masks a lifetime of insecurity about belonging, stemming from her mysterious adoption and the absence of biological roots. Over time, Goldie transforms from an awkward, self-deprecating young woman into a determined survivor and storyteller, confronting the trauma intertwined with her birth.

Her creative spirit as an aspiring writer mirrors her emotional journey: she’s always searching for truth beneath appearances, crafting meaning from chaos. Goldie’s relationship with Noah begins as a flirtatious accident but grows into something intense, raw, and dangerous, forcing her to balance love with suspicion when his secrets threaten everything.

By the novel’s end, Goldie’s evolution is profound—she moves from being defined by her past to actively reclaiming it, turning horror into art, and ultimately confronting her biological father, the monster who shaped her origins.

Noah (Davis Keller)

Noah—or rather Davis Keller—serves as both love interest and tragic hero, embodying the duality of protector and haunted soul. His initial charm, easy wit, and gentleness toward Goldie conceal a deeply fractured identity.

His past, tied to the horrific Camp Weonoke massacre, has left him with survivor’s guilt and a constant shadow of paranoia. Noah’s life is built on concealment—of his real name, his father’s crimes, and the violence he’s inherited.

Yet, despite his bloodline, he resists the darkness that shaped him, channeling it into tenderness and protectiveness toward Goldie. His relationship with Chase provides glimpses of loyalty and found family, contrasting the absence of biological connection.

As the story unfolds, Noah’s secrets erode the trust he builds with Goldie, and his inner battle between love and fear intensifies. His confrontation with Billy becomes both literal and symbolic—a son rejecting his monstrous inheritance.

Ultimately, Noah’s journey is one of redemption through love, his vulnerability proving that one’s lineage doesn’t dictate one’s humanity.

Evie

Evie, Goldie’s vivacious sister, brings levity and fierce loyalty to the otherwise grim narrative. As a special-effects artist who thrives on gore and theatricality, she represents the playful yet resilient spirit that helps both sisters endure trauma.

Her relationship with Goldie is filled with teasing and affection, yet beneath the sarcasm lies deep devotion; Evie acts as both protector and provocateur. She often bridges the gap between the ordinary world and the horror surrounding them, her love for cinematic violence contrasting with the real terror they eventually face.

Evie’s interactions with Chase add humor and heart—her fiery temper and quick wit clashing with his charm, hinting at an opposites-attract dynamic. In the climax, Evie’s courage and quick thinking parallel Goldie’s growth, proving her to be more than comic relief.

She embodies sisterhood in its truest sense: chaotic, loyal, and unyielding in the face of danger.

Chase

Chase is the comic foil and emotional glue of the group—a flirtatious, irreverent chef whose loyalty to Noah transcends superficial bravado. Initially, he appears as a carefree womanizer with a sharp tongue and a penchant for stirring trouble, but his actions reveal a deep sense of loyalty and selflessness.

His playful rivalry with Evie creates much of the novel’s comedic relief, yet their chemistry suggests an emotional undercurrent that humanizes both. Chase’s protective instincts toward Noah and Goldie come to light in moments of crisis, particularly when he risks his life during the climactic confrontation at Camp Weonoke.

His survival, despite grave injuries, reinforces his symbolic role as the resilient friend who keeps humor alive even amid tragedy. Chase represents the value of chosen family—the people who stay when bloodlines fail—and provides the warmth and irreverence that balance the novel’s darkness.

Billy Bromley

Billy Bromley is the malignant force threading through generations of horror in One Killer Night. His evolution from an obsessive, humiliated camp worker into a sadistic killer blurs the line between victim and villain.

Once a boy consumed by love and resentment, Billy becomes the embodiment of corrupted passion—a man whose obsession with ownership and revenge defines his entire life. His relationship with Sonny begins as a perverse love story and decays into possession and violence, culminating in the massacre that haunts the narrative.

Billy’s reappearance decades later ties the story’s past and present, revealing not only his survival but his continued desire for control, now focused on his biological daughter, Goldie. His claim of paternity transforms horror into an existential crisis for Goldie, forcing her to reconcile her identity with monstrosity.

Billy’s death at Noah’s hands is both an act of justice and tragedy, ending a generational curse but leaving the scar of inherited trauma.

Sonny

Sonny, though present mainly in flashbacks, serves as the emotional fulcrum of the novel’s past timeline. Her story at Camp Weonoke—trapped between Billy’s obsession and Davis’s cruelty—sets the foundation for the tragedy that reverberates through Goldie’s life decades later.

Sonny’s complexity lies in her vulnerability and her attempts to survive in a system that objectifies and silences her. She is both victim and catalyst: her entanglement with Billy triggers his descent, and her death cements the legend that drives the novel’s horror.

Sonny’s connection to both Davis and Billy foreshadows the intertwined destinies of Noah and Goldie, making her a ghostly presence who symbolizes the price of unchecked desire and betrayal.

Davis (Senior)

Davis, the charismatic counselor at Camp Weonoke, represents the dangerous allure of power and privilege. On the surface, he’s the charming leader every camper admires; underneath, he is manipulative, entitled, and morally corrupt.

His treatment of Billy—taunting and dehumanizing him—becomes the match that ignites the massacre. Davis’s cruelty exposes the class and social divides at the camp, contrasting the privileged counselors with the working-class “townie.” His legacy lingers through Noah, not as biological lineage but as an inherited name and trauma.

Davis’s role in the tragedy underscores one of the novel’s central themes: how cruelty, disguised as superiority, perpetuates cycles of violence.

Themes

Trauma and Survival

The emotional and psychological weight of trauma anchors One Killer Night, shaping the characters’ decisions and their relationships. The book opens with a violent prologue that sets the tone of fear and survival, depicting how trauma lingers long after the event itself.

This early horror connects directly to the later lives of characters like Goldie and Noah, who carry inherited scars from the massacre at Camp Weonoke. Their bond becomes both a coping mechanism and a mirror for their haunted pasts.

For Goldie, the trauma is layered—she has abandonment woven into her identity as an adopted child and later must confront the revelation that her biological father is a murderer. Noah’s trauma, in contrast, is tied to guilt, secrecy, and the burden of legacy as the son of a killer.

Both characters struggle between wanting normalcy and fearing they are doomed to repeat the past. The novel treats trauma as cyclical, showing how it ripples across generations through secrecy and repression.

Even moments of levity—Goldie’s humor, Evie’s sarcasm, or Noah’s flirtation—are tinged with a sense of fragility. The act of surviving, in this context, becomes more than escaping physical danger; it means learning to live with the unseen scars.

When Goldie confronts her past in the final scenes, survival transforms into reclaiming power. She refuses to be defined by her lineage, proving that trauma may shape identity but does not have to dictate destiny.

Identity and Inheritance

Identity operates at the heart of One Killer Night, not merely as a matter of self-discovery but as a confrontation with the truths hidden in one’s bloodline. Goldie’s identity journey begins with her being an adopted child—someone whose origin story was left blank—and culminates in the horrific revelation that her biological father is Billy, the killer at the center of the Camp Weonoke massacre.

The novel explores how identity can be both self-made and inherited, and how the two often conflict. Goldie constructs her life around humor, creativity, and love, trying to fill the void of not knowing where she comes from.

Yet as she digs deeper, she learns that her past is not empty but terrifyingly full. The inheritance of violence complicates her sense of self; she must decide whether blood defines her morality.

Noah experiences a parallel journey, growing up under the shadow of his father’s crimes and choosing reinvention through lies—changing his name from Davis Keller to Noah Adler. His reinvention underscores the novel’s question: can one truly escape who they are?

Both characters ultimately reject the deterministic power of inheritance. Their union at the end—marked by marriage and artistic creation—serves as an act of redefinition.

Identity, the novel suggests, is not static or purely biological but something constantly rebuilt through love, truth, and resilience.

Love and Redemption

In One Killer Night, love functions as both salvation and vulnerability. The romance between Goldie and Noah begins with light-hearted playfulness but gradually deepens into an emotional refuge against the darkness surrounding them.

Their connection humanizes the narrative’s violence, illustrating how affection can offer a sense of grounding even when the world feels unstable. For Noah, love becomes a chance at redemption.

Haunted by his father’s crimes and his own history of deceit, he sees Goldie as proof that he can build something pure from the wreckage of his past. His protectiveness, sometimes verging on paranoia, reflects his fear that he cannot preserve the good he has found.

Goldie, too, uses love as a form of healing—her affection allows her to trust despite betrayal and fear. The novel complicates love by setting it against horror; intimacy and terror coexist, forcing the characters to prove their devotion in extreme circumstances.

The final scenes, where Goldie and Noah survive and later marry, transform love into an act of defiance. Their bond rejects the violence that created them, rewriting their families’ histories through compassion.

Redemption in this story does not mean erasing the past but learning to live truthfully in its aftermath, with love serving as the bridge between pain and hope.

The Past’s Grip on the Present

Throughout One Killer Night, the past exerts a constant, almost suffocating pressure on the present. Every joyful or ordinary moment carries the echo of past crimes and buried secrets.

The massacre at Camp Weonoke, though decades old, shapes every major event in the book—from Noah’s hidden identity to the recurrence of the killer’s violence. The novel uses this haunting continuity to show how unresolved evil festers in silence.

Goldie’s adoption initially appears to free her from history, but as the story unfolds, her roots in that violent past drag her back into danger. Similarly, Noah’s attempt to reinvent himself collapses once his old name—Davis Keller—resurfaces, proving that reinvention cannot succeed without confrontation.

The Camp Weonoke legend functions as both literal and symbolic reminder: horrors buried without acknowledgment always return. Even the romantic and domestic aspects of the narrative are touched by this theme; the couple’s love story is shadowed by lies born from fear of the past.

By the end, when truth is forced into the open and the past literally resurfaces in the form of Billy, the novel suggests that liberation comes only through facing what has been suppressed. The grip of the past loosens not when forgotten, but when confronted and understood.

Good, Evil, and Moral Inheritance

One Killer Night blurs the line between good and evil, exploring how morality is shaped by context, trauma, and bloodline. Billy represents the pure embodiment of unchecked evil—his violence justified by his delusions of love and betrayal.

Yet the narrative resists simplifying his legacy. Through Noah and Goldie, it raises questions about whether the sins of parents are inevitably passed down to their children.

Noah’s entire life becomes a test of moral inheritance: he fears that the capacity for violence might be embedded in him, and this fear informs both his protectiveness and volatility. Goldie, upon learning she is Billy’s daughter, faces the same existential dread—that the darkness in her father might also exist in her.

However, both characters demonstrate through their choices that morality is not a product of lineage but of agency. Their acts of love, bravery, and truth-telling stand as counterpoints to Billy’s cruelty.

The novel also critiques society’s obsession with labeling people as “monsters” or “heroes,” showing how both terms can obscure human complexity. In the end, Noah and Goldie’s survival represents not only physical triumph but moral victory—a declaration that goodness is something one must choose and nurture, even when born from the darkest origins.