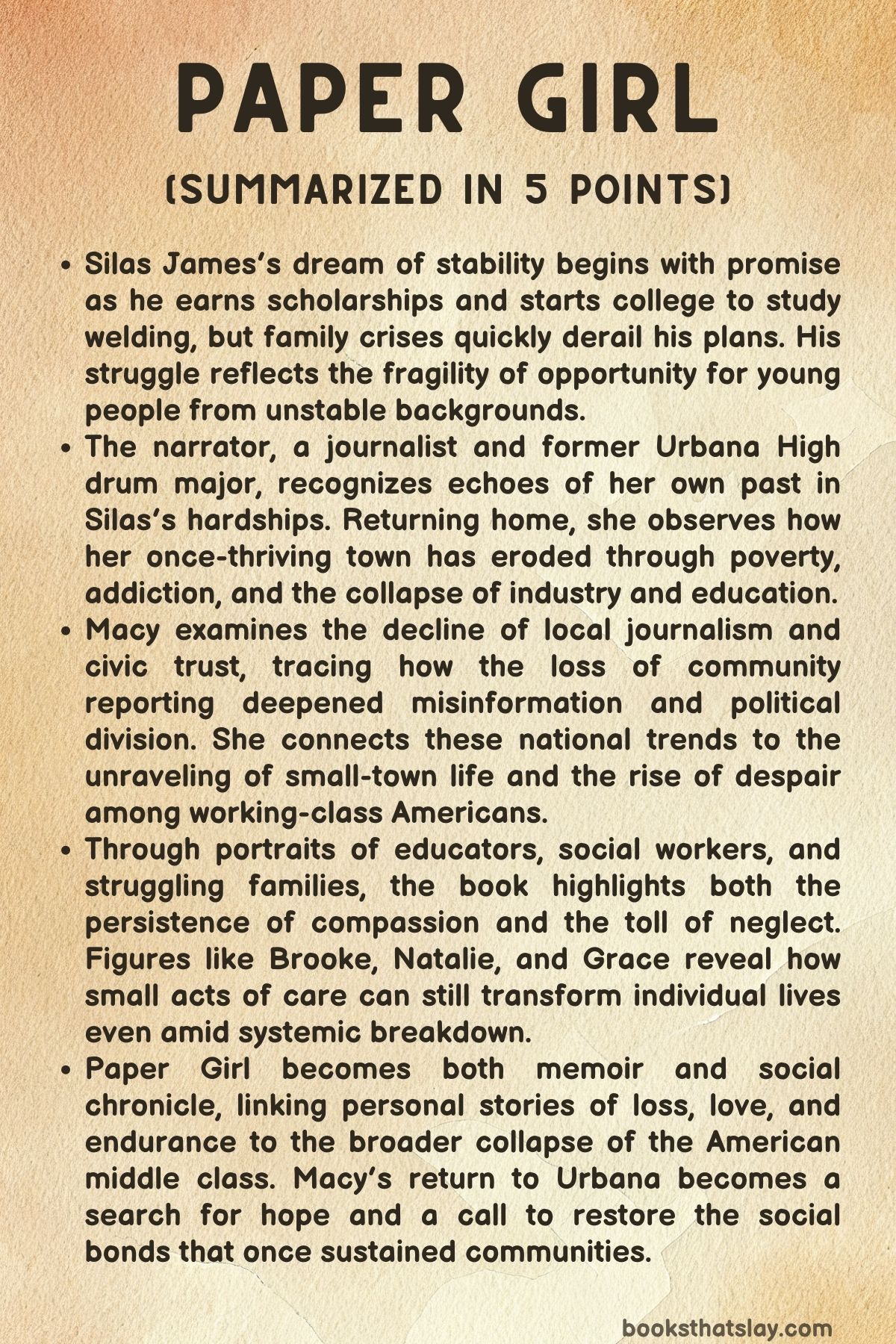

Paper Girl by Beth Macy Summary and Analysis

Paper Girl by Beth Macy is a deeply reported memoir that examines the unraveling of small-town America through the intersecting lives of ordinary people in Urbana, Ohio. At its center is the narrator along with Silas James, a young transgender man whose coming-of-age unfolds against the backdrop of economic collapse, addiction, and the erosion of public trust.

Macy, returning to her own hometown, uses Silas’s story—and that of her own family—to explore how deindustrialization, broken institutions, and the disappearance of local journalism have reshaped the meaning of community. Both personal and political, the book captures America’s loss of connection and its uncertain search for renewal.

Summary

Silas James, eighteen and newly graduated from Urbana High School, begins his adult life with cautious optimism. After a turbulent childhood marked by poverty, addiction, and instability, he earns two scholarships to Clark State Community College to study welding—a path he views as both practical and creative.

For a brief moment, his life seems to gain direction. But within days of starting college, his car breaks down, and a relative he lives with suffers a serious concussion.

Forced to quit school to care for her, Silas’s hopes collapse as quickly as they had formed, echoing a lifetime of interrupted beginnings.

Silas’s graduation had been filled with contradictions: joy mixed with the absence of loved ones. His grandparents rode four days from Texas to celebrate but missed the ceremony due to their inability to drive at night.

His counselor, Mrs. Flowers, arrived at his chaotic party with a small cash gift, while his sister stayed away. Throughout high school, Silas’s teachers and counselors had built a web of support—arranging rides, food, and emotional guidance.

His place in the marching band, where he rose to drum major, gave him pride and belonging. It was there that he found refuge in music, mentorship, and discipline.

During that time, he came out as transgender and adopted the name Silas, a choice that symbolized both strength and a rooted sense of self.

The narrator—Macy herself—sees in Silas a mirror of her own past. Like him, she grew up poor in Urbana, once a thriving manufacturing town.

When she was young, education and hard work could still lift a person out of hardship. Now, the same paths are blocked by rising costs, decaying infrastructure, and vanishing public investment.

The author contrasts her generation’s optimism with Silas’s, whose community has been gutted by factory closures, collapsing unions, and widening inequality. The erosion of education funding, especially the shrinking value of Pell Grants, has made college nearly impossible for low-income youth.

As opportunities vanish, despair fills the void—manifested in addiction, homelessness, and suicide.

Silas’s story unfolds as an emblem of these larger forces. His father died from an overdose, his mother cycles in and out of jail, and he has survived homelessness and abuse.

Teachers act as stand-ins for parents, yet even their support cannot insulate him from poverty’s relentless pull. His school’s once-mighty marching band has dwindled to a fraction of its former size, mirroring the town’s collapse.

Isolated and exhausted, Silas eventually reaches a breaking point, sitting alone with a knife and pills, contemplating ending his life.

Macy juxtaposes this with her own childhood in Urbana’s postwar golden era. The town once thrived on manufacturing, education, and civic pride, led by figures like Warren Grimes, whose airplane-light factory defined the local economy.

But as industries moved overseas, the foundation crumbled. Poverty deepened, social ties weakened, and resentment grew.

Where the town once championed learning and cooperation, division and apathy took hold. Confederate flags began to appear where Union ones once flew.

Political polarization fractured families—including Macy’s own.

The decline of local journalism becomes one of the book’s central motifs. Macy recounts the closure of historic papers like The Jefferson Herald, victims of the digital economy that drained ad revenue while exploiting journalistic labor.

With the death of local news came the death of shared reality. Residents, now informed by partisan social media, turned against each other.

Misinformation flourished, trust vanished, and civic life withered. Macy describes old newspaper boxes repurposed to distribute naloxone, a haunting symbol of how journalism’s collapse parallels addiction’s rise.

Her mother’s final years unfold against this backdrop of national fracture. Suffering from dementia, she retains humor and spirit—joking about memory loss, dancing, and finding companionship in assisted living.

Yet her decline coincides with the country’s own: the 2020 election divides the family even at her bedside. Macy’s siblings and friends split over politics, with some embracing conspiracy theories, others retreating from dialogue entirely.

Local newspapers, stripped to skeleton staffs, can no longer mediate truth. The Urbana Daily Citizen, once a fixture of civic life, prints only twice weekly.

The information vacuum allows extremism to take root, with some residents joining January 6 conspiracies or militias.

Meanwhile, the book introduces Brooke, a school liaison working at the front lines of Urbana’s social breakdown. She manages everything from truancy to child abuse cases, often entering homes filled with addiction, neglect, and violence.

Her stories—of students like Lindsey, who attacked her during a home visit, and Maddie, a survivor of sexual abuse—illustrate how trauma has become the norm for many children. Despite immense pressure, Brooke fights to keep them connected to school, often as the only adult consistently showing up for them.

The narrative also revisits Urbana’s buried racial history. The 1897 lynching of Charles “Click” Mitchell, a Black hotel porter falsely accused of rape, haunts the town’s conscience.

Mark Evans, Mitchell’s descendant, campaigns for recognition and memorialization, but encounters resistance. Many residents prefer silence over confrontation.

Evans’s work reveals the town’s long-suppressed racial wounds, exposing how denial perpetuates injustice.

Macy then turns to her sister Terry’s widowhood, marked by loss, humor, and gradual healing. Their family gathers for a memorial, bridging political divisions that had once seemed insurmountable.

Even the brother once estranged during the Trump years returns, seeking reconciliation. These scenes of fragile reunion suggest that small acts of empathy can still survive amid bitterness.

By 2024, Urbana’s annual county fair becomes a microcosm of America’s turmoil. Among livestock shows and food stalls, political activists argue over gun rights and abortion.

Local Democrats face hostility; misinformation spreads unchecked. The director of the Urbana Youth Center, Justin Weller, becomes the target of smear campaigns accusing him of corruption and grooming.

Undeterred, he and his staff provide lifelines for teens trapped in poverty, offering tutoring, meals, and jobs. One success story is Grace Slagle, an autistic teen who escapes homelessness with the center’s help—earning a GED, a job, and her own apartment.

Her transformation embodies the remnants of hope in a broken system.

Silas reappears near the book’s end. He has rebuilt parts of his life, working a steady job, living with his boyfriend Max, and caring for his younger siblings after their mother’s relapse.

Though still haunted by instability, he demonstrates quiet resilience. On Christmas Eve 2024, he proposes to Max—a moment of love and persistence against the odds.

The final scenes return to the narrator’s own reckoning. As the 2024 election plunges the nation into renewed conflict and fear, she trains briefly with a firearm but decides against owning one.

The gesture underscores her refusal to surrender to paranoia. She observes her town—its shuttered factories, its neglected schools, its hollowed-out newspaper office—and wonders whether America can still rebuild trust.

When Trump regains power and pardons January 6 rioters, the sense of unraveling deepens. Yet in Silas’s endurance, in Grace’s newfound independence, and in the quiet work of people like Brooke and Weller, Macy finds flickers of resilience.

Paper Girl closes not with resolution, but with determination: the belief that truth-telling and human connection, however fragile, remain the last tools for saving what’s left of community.

Characters

Silas James

Silas James stands at the heart of Paper Girl, embodying both the resilience and fragility of America’s forgotten youth. Once known as Elizabeth before coming out as transgender, Silas represents a generation caught between dreams of independence and the crushing weight of inherited instability.

His story is one of persistence amid systemic collapse—he navigates homelessness, family trauma, and the loss of opportunity with remarkable grit. Silas’s brief success at college and his passion for welding reveal his desire to build something lasting, not just in metal but in life.

Yet, the same social decay that eroded his hometown’s institutions thwarts his progress, forcing him into premature adulthood as caretaker and survivor. His courage to live authentically, despite poverty and prejudice, reflects an inner strength that defines him.

Still, beneath that strength lies exhaustion—a sense of futility mirrored in his moment of suicidal contemplation. Silas becomes the mirror through which the author explores the intersection of personal identity, economic despair, and the crumbling American promise.

The Narrator (Beth Macy)

The narrator of Paper Girl, Beth Macy, serves not merely as observer but as participant and chronicler of her community’s unraveling. Returning to Urbana after decades, she confronts the erosion of the very structures—education, journalism, social trust—that once enabled her own escape from poverty.

Through her reflections, Macy bridges the gap between generations, contrasting her own journey out of hardship with Silas’s entrapment in it. Her tone alternates between empathy and lament; she sees in Silas the echo of her younger self and in Urbana the ghost of a nation that has turned away from collective responsibility.

Macy’s dual perspective—as journalist and hometown witness—allows her to dissect systemic decline while maintaining a deeply human lens. Her voice is both elegiac and defiant, seeking meaning in the ruins of community life.

Ultimately, Macy becomes a moral compass in the narrative, urging readers to recognize that personal resilience cannot substitute for social justice.

Brooke

Brooke, the school liaison in Urbana, is one of the unsung heroes of Paper Girl, a symbol of compassion within broken systems. Her work transcends traditional education roles; she is part counselor, social worker, and first responder in the lives of neglected children.

Brooke’s daily encounters with addiction, abuse, and generational poverty highlight both her endurance and the deep fractures within the town’s social fabric. Her brutal assault by a student during an intervention underscores the physical and emotional toll of her labor.

Despite trauma, Brooke persists, reflecting the kind of moral courage rarely acknowledged in public narratives. She becomes a grounding force amid the chaos, offering fragile hope through human connection, even when institutions fail to support her.

Grace Slagle

Grace Slagle’s transformation from an abandoned, autistic teenager to an independent young woman forms one of the most uplifting arcs in Paper Girl. Initially trapped in neglect and homelessness, Grace embodies the consequences of systemic failure—but through the guidance of Natalie Yoder, she discovers autonomy.

Her journey is one of reclamation: learning hygiene, work skills, and emotional boundaries while resisting her mother’s manipulative demands. Grace’s story underscores the redemptive power of mentorship and compassion.

She stands as proof that intervention at the right time can redirect a life otherwise lost to poverty and trauma. Her newfound independence—a job, an apartment, and a sense of self-worth—offers a glimmer of hope in a landscape of despair.

Natalie Yoder

Natalie Yoder serves as both savior and sustainer in Paper Girl, representing the best of community action in a town otherwise paralyzed by division. As a mentor at the Urbana Youth Center, Natalie devotes herself to rescuing children like Grace from neglect and homelessness.

Her nurturing yet disciplined approach blends empathy with practicality—she doesn’t simply provide shelter but teaches survival. Natalie’s relationship with Grace mirrors the kind of transformative care that institutions once offered but now rarely do.

In her, Macy captures the quiet heroism of ordinary citizens who step in where government and systems have retreated. Natalie’s work with the Youth Center also places her at the heart of Urbana’s political turbulence, showing how compassion itself becomes a radical act in a polarized America.

Justin Weller

Justin Weller, director of the Urbana Youth Center, symbolizes the embattled civic leader in a post-truth society. His tireless advocacy for youth empowerment meets with smear campaigns, defamation, and political retaliation—emblems of how truth and goodwill are weaponized in divided communities.

Weller’s resilience in maintaining the center despite threats and financial obstruction illustrates moral steadfastness under siege. He stands as a testament to the idea that progress now requires defiance against misinformation and fear.

Weller’s plight mirrors the decay of local journalism and public trust that the book chronicles, transforming him into both victim and visionary—a modern figure of integrity in an age of suspicion.

Heather Tiefenthaler

Heather Tiefenthaler emerges as a figure of civic conscience within Paper Girl, navigating the hostile terrain of small-town politics. As a Democrat in deeply conservative Urbana, she embodies both courage and vulnerability, confronting threats, disinformation, and the specter of political violence.

Her efforts to bridge divides and advocate for democratic values make her one of the book’s most quietly powerful voices. Tiefenthaler’s interactions with national thinkers reveal her awareness of the larger ideological war consuming rural America.

Yet her local activism remains deeply personal—rooted in the belief that communities can be healed through engagement rather than abandonment. She represents the conscience of small-town America, fighting for truth even as institutions crumble around her.

Terry

Terry, the narrator’s sister, provides an intimate counterpoint to the broader social collapse in Paper Girl. Living with disability from childhood polio, she experiences loss, love, and rediscovered independence after her husband John’s death.

Her resilience and humor soften the book’s heavier themes, illustrating endurance within domestic and emotional spheres. Terry’s gradual recovery of financial and emotional self-sufficiency mirrors the broader yearning for stability that permeates the narrative.

Her story also becomes a space for family reconciliation—where grief, faith, and affection coexist amid lingering political tensions. Through Terry, Macy explores how personal healing parallels the collective need for restoration.

The Narrator’s Mother (Cookie)

Cookie, the narrator’s mother, stands as both matriarch and metaphor within Paper Girl—a woman shaped by resilience yet diminished by time and illness. Her wit and stubborn independence remain intact even as vascular dementia steals her memory and autonomy.

Cookie’s friendship with Yvonne and their imagined escapes evoke a bittersweet defiance against aging and confinement. Through her, Macy captures the tenderness and tragedy of a generation that built the postwar middle class only to see its security dissolve.

Cookie’s final days, set against the backdrop of political polarization and family discord, encapsulate the emotional heart of the book: the struggle to preserve dignity, connection, and humor in a world coming apart.

Mark Evans

Mark Evans represents the moral historian of Urbana—a man determined to excavate buried truths. As a descendant of Charles “Click” Mitchell, the lynched Black porter, Evans seeks justice through remembrance.

His research and activism confront the town’s denial of its racist past, positioning him as both truth-teller and outcast. His interactions with white classmates reveal the discomfort that still accompanies racial reckoning in small-town America.

Evans’s persistence transforms him into a custodian of collective memory, refusing to let silence bury the crimes of history. Through him, Macy exposes the tension between reconciliation and accountability, reminding readers that healing requires confrontation, not forgetfulness.

Maddie Allen

Maddie Allen’s story threads resilience through trauma. Once a promising student, she endures sexual abuse, family instability, and poverty, yet continues striving for education and purpose.

Her decision to pursue addiction counseling after surviving her own crises demonstrates the cyclical nature of compassion born from suffering. Maddie’s perseverance in working multiple jobs and studying online underscores the endurance required of young people in communities abandoned by opportunity.

Through her, Paper Girl reaffirms that survival itself can be an act of defiance—and that hope often persists, quietly, in those society overlooks.

Themes

The Erosion of the American Dream

In Paper Girl, the decline of the American Dream is illustrated through the interwoven lives of Silas, the narrator, and the people of Urbana. The story traces how generational poverty, the collapse of local industries, and dwindling educational support systems have replaced upward mobility with resignation.

Silas, a young man of extraordinary perseverance, embodies the thwarted promise of a system that once rewarded hard work and ambition. His scholarships and early academic promise symbolize the remnants of that dream, but his withdrawal from college due to familial crisis exposes how fragile opportunity has become for those without social or financial safety nets.

The narrator’s reflection on her own escape through education decades earlier underlines the widening gulf between past and present. Where Pell Grants and factory jobs once provided ladders out of poverty, now bureaucracy, tuition inflation, and precarious work leave young people stranded.

This transformation of Urbana from a community of striving workers into one of survivalists mirrors America’s broader economic and moral decay. The American Dream here is not simply deferred—it is systematically dismantled by policies that prioritize profit over people and by cultural forces that breed division rather than solidarity.

The once-shared faith in progress and self-betterment has withered into cynicism, leaving individuals like Silas to shoulder the burden of societal failure alone. The novel mourns this loss not as a nostalgic longing but as an indictment of a nation that has abandoned its most vulnerable.

Decline of Community and the Collapse of Local Journalism

The disappearance of local journalism in Paper Girl functions as both a metaphor and a mechanism for the unraveling of civic life. Urbana’s decaying newspapers symbolize the erosion of truth, connection, and accountability within small-town America.

The narrator’s observations about the fall of Herald Publishing and the repurposing of newspaper boxes into naloxone dispensers create a powerful image of transformation—from information that sustained democracy to medication that sustains survival. The shift from community-driven reporting to social media outrage signifies a broader collapse of shared understanding.

Without local news, citizens no longer see themselves as part of a collective story; they become isolated, suspicious, and susceptible to disinformation. The narrative links this decline to the corrosive influence of digital corporations, protected by outdated legislation like Section 230, which enables platforms to amplify division without responsibility.

The resulting environment nurtures conspiracy theories, political extremism, and social alienation. In Urbana, neighbors turn against one another, unable to distinguish fact from manipulation.

This disintegration of trust extends into families and schools, leaving educators and civic workers to fill voids once occupied by community institutions. The novel’s portrayal of the dying press underscores that democracy cannot survive without credible local storytelling—it is through these shared narratives that empathy and accountability once flourished.

The decline of journalism thus parallels the decay of moral infrastructure, showing how truth itself has become a casualty of neglect and greed.

Poverty, Addiction, and the Burden of Survival

Poverty and addiction in Paper Girl are not presented as isolated tragedies but as systemic consequences of abandonment—economic, political, and emotional. Silas’s story reveals how instability breeds despair across generations: an incarcerated mother, an addicted father, and a cycle of loss that forces children into premature adulthood.

His reliance on marijuana, his exhaustion from caretaking, and his near-suicidal collapse are portrayed with unflinching empathy. Parallel accounts of students like Maddie Allen and Grace Slagle expand this portrait of rural hardship, showing how trauma, homelessness, and neglect intertwine with the failures of institutions meant to protect youth.

Educators like Brooke and Yoder become de facto social workers, navigating crises that stretch beyond the classroom. Addiction here is both a symptom and a metaphor—representing a society self-medicating against its own moral and economic decline.

Factories that once offered identity and stability have been replaced by temp jobs and fentanyl. The despair of Urbana mirrors a nation numbed by inequality and disillusionment.

Macy’s portrayal avoids sensationalism; instead, it humanizes poverty by showing its emotional toll—the fatigue, the quiet dignity, the flickering hope. Poverty in this narrative is not a moral failing but a consequence of structural cruelty.

Survival becomes an act of resistance, and each small victory—a GED earned, a child rescued, a relationship reconciled—becomes a testament to the endurance of those whom society has written off.

Political Polarization and the Fracturing of Truth

Political division saturates Paper Girl, shaping not only public discourse but private relationships. The narrator’s family, once bonded by shared struggle, becomes emblematic of a nation at war with itself.

Arguments erupt at hospital bedsides and funerals; siblings and old friends sever ties over conspiracy theories; and local elections become battlegrounds of ideology rather than governance. The novel exposes how misinformation, amplified by the vacuum left by dying local media, transforms communities into echo chambers of resentment.

Urbana’s transformation—from a union-strong, working-class town to one filled with Confederate flags and extremist sympathies—reflects the distortion of identity that comes when history is forgotten and fear replaces empathy. Macy does not reduce this divide to caricature; instead, she explores how economic despair and cultural isolation create fertile ground for radicalization.

Characters like Heather Tiefenthaler and Justin Weller struggle to uphold civic engagement amid threats and lies, while educators and social workers confront the tangible consequences of polarization: withdrawn funding, distrust, and violence. The novel suggests that America’s political fracture is not purely ideological—it is existential.

Truth itself has become partisan, and reality negotiable. By showing how misinformation erodes both democracy and intimacy, Macy warns that without a revival of shared purpose and honest dialogue, the nation risks consuming itself from within.

Education as the Last Fragile Lifeline

Education stands as both a sanctuary and a battlefield in Paper Girl. For Silas, it represents the only plausible escape from generational hardship, yet every institutional safeguard that once upheld that promise has weakened.

Teachers and mentors replace absent parents, struggling against an underfunded, overstretched system. The narrator’s reflection on her own college years—when federal grants enabled her to rise from poverty—underscores how much opportunity has receded.

In contemporary Urbana, students must work multiple jobs, care for siblings, or fight trauma just to stay in school. The educators depicted—Brooke, Flowers, and others—labor not just to teach but to preserve faith in the possibility of learning itself.

Attendance laws, diversion programs, and interventions attempt to compensate for what has been lost at home, but bureaucracy often blunts their impact. The contrast between Silas’s artistic drive in welding and his economic entrapment highlights a central paradox: education still holds transformative potential, but only for those who can afford stability long enough to access it.

The book treats education as the last remaining thread connecting individuals to collective hope. Yet, as Urbana’s dropout rates rise and public trust in institutions crumbles, that thread frays.

Macy portrays classrooms as microcosms of the nation—filled with resilience, disillusionment, and unfulfilled promise. In the end, education remains the most fragile yet vital tool for restoring what America has lost: belief in a future worth striving for.