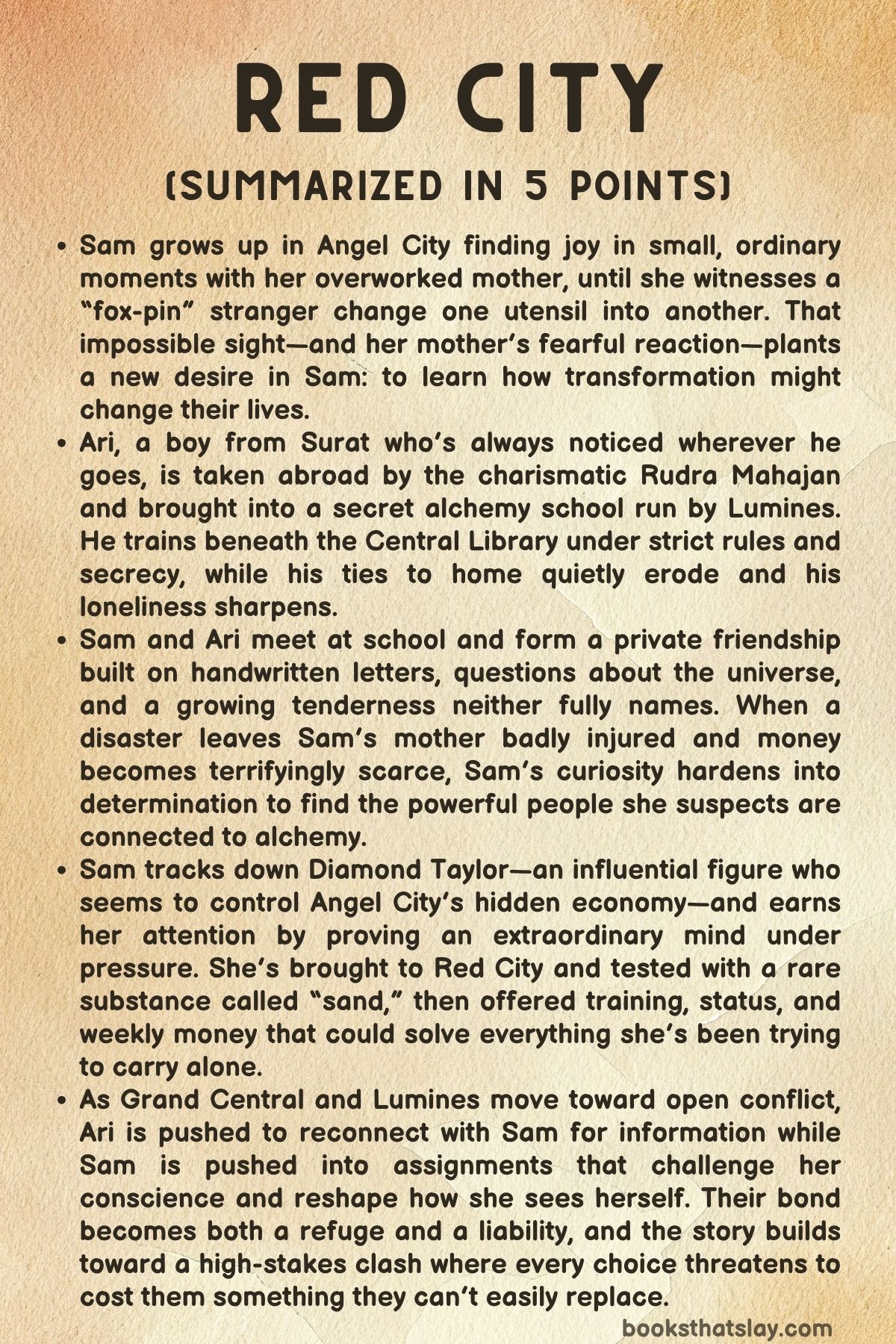

Red City by Marie Lu Summary, Characters and Themes

Red City by Marie Lu is a near-future crime fantasy set in Angel City, California, where a hidden alchemical underworld quietly shapes wealth, beauty, and power. The story follows Sam, a working-class student with a flawless memory, and Ari, a boy taken from India and trained by a secret syndicate.

Their lives collide with Diamond Taylor, the city’s celebrated billionaire, whose empire runs on “sand,” a rare alchemical substance that perfects what it touches while demanding a brutal price. It’s a story about ambition, love, and what people trade away to feel safe, seen, and unstoppable.

Summary

Sam grows up in Angel City with her mother in a small apartment that still feels magical to her because she notices every detail—the cracks in the ceiling, the weeds in the sidewalk, the meals her mother improvises after long shifts at a Chinese restaurant called Mandarin Palace. Sam’s mother works constantly, stretching wages that never last.

Sam accepts their life until one day she witnesses something she can’t explain: two elegant men with gold fox pins speak in coded terms at the restaurant, and one of them changes a utensil in his hand as if matter can be rearranged by thought. Sam’s perfect memory confirms she didn’t imagine it.

Her mother’s fearful reaction tells Sam the truth is dangerous.

Sam begins obsessively researching alchemy, especially rumors around Diamond Taylor, a public philanthropist and corporate titan whose influence dominates the city. When Sam’s mother finds her search history, she erupts—not only angry, but terrified—and destroys Sam’s treasured stuffed rabbit in front of her.

The threat is clear: stop looking. Sam promises, but the violence only hardens her need to understand what’s real and why her mother is so afraid.

Elsewhere, Ari grows up in Surat, India, always drawing attention for his striking looks. A man calling himself Prometheus demonstrates a miracle by turning dirt into an ice cream bar.

The next day, Ari is taken abroad with his mother’s consent, transported into a world he never chose. In Angel City, Prometheus—Rudra Mahajan—places Ari in luxury and enrolls him in Lumines, a secret organization that trains alchemists beneath a grand gallery near the central library.

Ari learns alchemy as a strict science of balance and transformation. He also learns its rules: you can refine and reshape matter, but you cannot restore a soul or bring the dead back.

Students adopt “attributions,” names of historic figures, to symbolize immortality. Ari works relentlessly, while Rudra intercepts his letters home, cutting him off until his language and family begin to feel distant.

At school, Ari meets Sam, who seems invisible to everyone else. Her quiet presence is a relief in a life where he can’t escape being noticed.

They form a friendship through handwritten letters—questions, theories, jokes, and wonder about light, time, and what makes a person real. They keep secrets: Sam hides her hunger for alchemy; Ari hides that he is an alchemy student.

Over time, the friendship turns into something gentler and more intimate, especially during a rainy wait in the library when Ari tells her, in his own symbolic way, that he likes her exactly as she is.

Sam’s life fractures when Mandarin Palace explodes. Her mother survives but is badly burned, and the bills and pain push them deeper into desperation.

Sam tries to hold everything together—cooking, caretaking, searching for work—while her mother forces herself through interviews that always end in rejection. Sam feels trapped by poverty and by the sense that she and her mother can be discarded by the city without consequence.

Then Sam has a nightmare about Diamond Taylor harming her, and the image sticks. She remembers whispers that Diamond can erase debts and make wishes come true.

Sam goes to the Odyssey Theater on the opening night of a show called Firefly, sneaks inside, and finally sees Diamond in person, surrounded by fox-pin associates. When Diamond leaves, Sam follows and overhears a conversation about rival syndicates, a substance called sand, and a coming conflict.

Diamond’s son, Will Taylor, detects Sam, and she’s dragged out. To survive, Sam proves her memory by repeating their exact words and reciting long sequences of pi.

Diamond tests her again with complex notes, then offers her a chance: return tomorrow.

Will brings Sam to Red City, the Taylors’ fortified estate, where Grand Central operates as an alchemy syndicate masked as a corporation. Sam learns sand is refined from the philosopher’s stone and enhances a person’s gifts and appearance, pushing them toward “perfection.” Philosophers who can create it are rare and often die young.

Sam is evaluated at the Observatory, their training college. Given sand, her senses sharpen, and she discovers she can perceive the hidden structure of materials.

Blindfolded, she identifies elements by touch, sensing their internal patterns. She passes a test no novice has ever passed so quickly.

Will pays her $2,000 as her first weekly wage and promises she will never fear money again.

Soon, violence becomes the cost of belonging. After an attempt on Will’s life, Diamond prepares retaliation against Lumines.

Sam is assigned to work with Sebastian, a killer Diamond recruited and empowered. He forces Sam into her first murder during a hunt for Lumines operatives.

She follows orders, but afterward she is sick with guilt and panic, scrubbing her hands raw. Diamond rewards loyalty with money and attention while pressuring Sam to harden herself, reminding her that value is something you must defend.

Meanwhile, Lumines orders Ari to reconnect with Sam and use their history as a channel into Grand Central. Ari is torn between duty and the person Sam was to him.

His efforts to live normally fail; even during a date with Charlotte, the police chief’s daughter, he can’t stop thinking about Sam. When Sam and Ari meet again at a moonlit beach, they approach each other like enemies, weapons ready, then talk like people who never finished a sentence years ago.

They agree to meet again each full moon, still unsure whether they are reconnecting or circling a trap.

The syndicate war escalates. Hanover, one of Diamond’s people, is captured and returned dead after torture.

Diamond decides to break a taboo and target a Lumines philosopher at an Oxford conference. Sam travels with Will under false pretenses, dressed and prepared to enter the highest circles of their world.

But Sam has been planning her own counterstrike: she contacts the police, intending to expose Grand Central.

Diamond discovers Sam’s betrayal. Sam is captured and punished with extreme cruelty, left broken and abandoned.

She nearly dies, repeating her mother’s voice in her mind—always try—until she is rescued by Dr. Amerson, an alchiatrist once connected to Diamond. Amerson saves Sam out of conscience and because Will secretly asked her to, but Sebastian murders Amerson before the fallout can end.

A prisoner exchange at Red City collapses into chaos when Diamond orders executions and the police raid the estate—set in motion by Sam’s testimony. In the gunfire, Sam rescues Ari, guiding him toward an escape tunnel.

Will intercepts them, and the confrontation becomes an alchemical fight with lethal stakes. Sam, barely able to stand, uses her remaining strength to drive a golden spike through Will’s chest, and she and Ari escape long enough for Sam to make a final choice: Ari must flee while she stays as the police’s key witness.

Ari leaves, devastated. Sam surrenders as helicopters flood the night sky over the ruined estate.

Diamond dies in custody, sick and alone, clinging to the memory of what she built and what it cost. Sam is released, but she is not free inside herself.

Sebastian finds her and offers a new path: Grand Central can be rebuilt under a different leader in Londinium, and Sam has a place waiting. She accepts, telling herself she will destroy the system from within, while also admitting the darker truth—she cannot fully let go of the world that finally gave her power and security.

Ari survives abroad, learning his family is finally safe, yet realizing he no longer belongs in the life he was taken from. When he hears Sam has joined a new syndicate, he mourns what they lost and what still pulls him forward.

With a letter of love and regret in hand, he turns toward the sea and sets his course for Londinium, moving toward the place where Sam’s choice has taken her.

Characters

Sam

In Red City, Sam begins as a girl who treats scarcity like a kind of art: she notices beauty in cracks on the ceiling and weeds on the sidewalk, and that tenderness becomes her earliest form of power. What makes her dangerous later is that the same attention that lets her romanticize a tiny apartment also lets her recognize patterns other people miss.

Her near-perfect memory is not just a “gift” but a moral pressure-cooker—she can’t unknow what she has seen, can’t dilute it with denial, and that makes her both brave and brittle. Sam’s central conflict is hunger: hunger for safety, for rest for her mother, for a life that doesn’t feel like constant subtraction.

Alchemy becomes the language of that hunger because it promises transformation without apology, and Sam’s arc shows how quickly a desire to protect can evolve into a desire to control.

Once Grand Central takes her in, she learns that being “seen” by power is a drug of its own, as intoxicating as sand. Sam’s first kill marks a decisive shift: she doesn’t only get pulled into violence; she chooses it under pressure, and the aftermath—vomiting, compulsive hand-washing, weight loss—reveals how her conscience fights to stay intact even as her environment rewards numbness.

Her relationship with Ari complicates everything because he represents a version of her life where secrecy was intimate rather than predatory: letters, quiet attention, a love that doesn’t demand she become someone else. Yet by the end, Sam’s choice to re-enter the underworld is not framed as simple corruption; it reads like an admission that she has been permanently altered.

She wants freedom, but she also wants belonging and agency, and she convinces herself that the only way to end the syndicate is from inside—even if part of her is also returning because she no longer knows how to live without the sharp edges of that world.

Ari

Ari’s defining wound is visibility. He grows up as someone people look at, interpret, and claim, and he learns early that attention can be a cage.

That is why Sam fascinates him: she is “invisible” in the social landscape where he is always exposed, and she offers him the rare relief of being with someone who doesn’t treat him like an ornament or an object. His diligence in training is rooted in love and duty—he is trying to earn a future for his family—yet the tragedy is that the system he enters rewrites those motivations, gradually starving his language, his memories, and his sense of home.

The intercepted letters are a quiet cruelty that becomes enormous over time: Ari doesn’t simply miss his family; he is engineered to forget them.

Ari’s moral struggle is less about whether he is capable of violence and more about whether he can remain a whole person inside an institution that demands compartmentalization. His attempts at normalcy—like dating Charlotte—collapse because Sam is not just a crush; she is the last link to a self that existed before his training became a total identity.

His use of bioalchemy in intimacy shows how power leaks into the most private places, turning even pleasure into performance and manipulation, and it leaves him disturbed because he senses what he is becoming. When Lumines orders him to reconnect with Sam as an instrument, he is forced into the worst version of his childhood dynamic: being seen and used.

Still, his persistence in meeting her at the beach and his willingness to walk toward Londinium at the end suggest that Ari’s core desire is not dominance but reunion—he keeps choosing connection even when it threatens his safety, because connection is the only thing that makes his transformed life feel real.

Diamond Taylor

Diamond is the story’s clearest embodiment of controlled attention: she can sit “ordinary-looking” in a theater and still bend the room around her. Her power is built on a philosophy that greatness justifies cruelty, and she treats people as investments—assets to refine, spend, and discard.

The way she tests Sam is revealing: she is impressed not by kindness, but by utility and precision. Diamond’s mentorship is therefore a trap disguised as elevation; she offers money, status, training, and a new identity, but every gift is also a leash.

She is also profoundly hollowed out. Illness drains her, but the deeper decay is spiritual: decades of shaping others into tools has eroded her capacity to love without possession.

Even her relationship with Will is steeped in experimentation, legacy, and fear of weakness. Diamond’s willingness to wage war, target rivals, and violate taboos underscores that she sees morality as a story told by the winning side.

Yet her final memories complicate her villainy—not by absolving her, but by showing the private cost of her worldview. When she imagines reuniting with Peter as she dies, it suggests that beneath the empire and the sand, she is still driven by longing, and that longing has been distorted into a relentless need to control the world before it can take anything else from her.

Will Taylor

Will is the heir who has been trained to be a weapon while still being asked to remain a son. He carries the polish and authority of Grand Central, but his interactions with Sam hint at a quieter complexity: he can be threatening and magnetic, yet he also seems to recognize parts of her that mirror his own captivity inside Diamond’s expectations.

His role as Sam’s guide into Red City is layered with power imbalance—he is the gatekeeper to money, safety, and knowledge—yet he’s also someone who appears to understand what it means to be shaped by a system that calls itself “perfection.”

His inability to kill Sam when ordered suggests a fracture between what he has been taught to do and what he can actually bear to do, and that fracture matters. In the final duel, Will becomes the personification of institutional force: skilled, relentless, and sure of his right to win.

Sam’s decision to impale him is not only self-defense; it is her severing of the path where she could have become his counterpart inside Diamond’s world. The later implication that his body is missing keeps his character hovering in ambiguity—either as a literal survival or as a symbol that legacies like his don’t disappear cleanly.

He is, in a sense, the most personal cost of Sam’s war: the person she kills who also represents the version of her life that might have stayed inside Grand Central without rebellion.

Sebastian

Sebastian is what the alchemical underworld produces when the soul is treated as expendable. He narrates himself as an artist of killing, which is both a defense mechanism and a recruitment tactic: by aestheticizing violence, he tries to make it contagious.

His presence functions as an initiation ritual for Sam—he is the mentor who teaches her the practical reality of what Grand Central’s power means on the street. The porcelain-and-tile murder is not just brutality; it is spectacle, a demonstration that alchemy can erase the line between body and environment, turning a person into “evidence” that can be rearranged.

What makes Sebastian especially chilling is his predictability. He is loyal to power, not people; he kills because it is his purpose and because the syndicate has given him a context where his worst impulses are rewarded.

The summary’s warning that decades in alchemy leave “empty shells like Sebastian” positions him as a cautionary endpoint: skill without empathy, identity without humanity. Even after Diamond’s fall, he persists as the recruiter of the next regime, tempting Sam back with offers and half-truths.

He is the voice of the underworld saying, “You’re one of us now,” and the fact that he can say it with confidence shows how successfully the system converts trauma into allegiance.

Rudra Mahajan

Rudra is the predator who wears the mask of opportunity. As Prometheus, he performs “miracles” to seduce Ari into believing transformation is a gift rather than a transaction.

His true power lies not only in alchemy but in logistics: he isolates Ari in luxury, controls his communication, and slowly edits his identity until the boy’s family becomes a faint blur. Intercepting letters is a profoundly intimate violation, a way of ensuring that Ari’s loyalty can only flow upward toward the organization.

Rudra also represents a specific kind of institutional cruelty: punishment framed as correction. Isla’s history with him shows how the system disciplines attachment, especially when it threatens secrecy.

His role at the prisoner exchange underscores his willingness to treat lives as bargaining chips and casualties as acceptable losses. In the story’s ecosystem, Rudra is not simply a villainous individual; he is a mechanism of recruitment and retention, proving that the most effective oppressors are often those who can make exploitation look like destiny.

Isla

Isla is severity shaped into a protective shell. As a tutor and enforcer within Lumines, she believes in rules because she has seen what happens when rules break—particularly to women who become “personally involved” in ways the syndicate disapproves of.

Her warning to Ari is not moralizing; it is fear translated into discipline, the voice of someone who has survived the consequences of attachment and knows how quickly love becomes leverage in a world built on secrets.

What makes Isla compelling is that she is both participant and witness. She trains others in power while quietly carrying the knowledge of how that power destroys.

Her later role—meeting Ari, telling him his family is free, and revealing Sam’s new alignment—positions her as a bridge between the personal and the political. She does not offer comforting illusions; she offers facts, boundaries, and the hard truth that survival often requires choosing what pain you can live with.

Reed

Reed functions as Lumines’ strategist, the person who turns relationships into access points. His directive to Ari about Sam is calculated: he wants nostalgia weaponized, intimacy converted into surveillance.

Reed’s leadership style, as implied here, is not about dramatic displays but about leverage and plausible deniability—using someone else’s feelings so the organization can reach into Grand Central without exposing itself.

In the prisoner exchange, Reed appears as one of the figures willing to gamble with chaos, and the collapse of the standoff shows the limits of strategy when pride and vengeance take over. Reed represents the idea that even the “rival” syndicate is not morally cleaner; it is simply differently organized, equally willing to bend people into tools.

Hanover

Hanover’s significance is partly structural: he is the connective tissue of Grand Central’s operations, the person tasked with supplier relations and the practical maintenance of an empire. His capture and tortured death are meant to be a message, and that is exactly why his character matters.

He embodies how syndicate wars are fought not only with philosophers and leaders but by brutalizing the workers who keep the machine running.

His death also escalates Sam’s role: losing Hanover becomes part of the chain that pulls her toward a philosopher assassination assignment. In that sense, Hanover is one of the story’s reminders that “eye for an eye” logic always spreads outward, consuming people who are not the original architects of conflict.

Maclan

Maclan, labeled “Kafka” within Lumines, becomes a victim whose death is designed to erase his humanity and turn him into a cautionary object. The method of his murder—being transmuted into porcelain and tile and fused to a bathroom—communicates Grand Central’s ethos: power should be seen, feared, and made unforgettable.

Maclan’s limited presence is purposeful; he is not developed as a full person in this summary because the syndicates themselves do not treat him as one.

His death is also Sam’s first step into deliberate violence, making Maclan a grim pivot-point: the moment her fear becomes complicity. The public ruling of “overdose” adds another layer, showing how institutions can transmute truth the way alchemists transmute matter.

Kane

Kane is the shooter whose capture reveals Diamond’s preference for terror as theater. The Confession Rooms, the camera, the implication of mutilation—these details frame punishment as performance meant to discipline not only the victim but the witnesses, including Sam.

Kane’s function in the story is to show what Grand Central does to threats and how it uses spectacle to keep its own members compliant.

The dumping of his mutilated body downtown is the final act of that spectacle: violence exported into the city as a warning. For Sam, Kane’s fate becomes part of her unraveling, because she is forced to stand near the edge of what the syndicate calls “necessary” and realize how quickly “necessary” becomes grotesque.

Charlotte

Charlotte, the police chief’s daughter, represents a doorway into a normal life that Ari cannot actually step through. On paper, she is safety: a socially acceptable relationship, a future not shaped by syndicate secrecy.

In practice, she becomes evidence of Ari’s dislocation. His inability to be present with her shows that his internal world has been occupied by Sam and by the moral stress of his double life.

The use of bioalchemy during sex turns Charlotte into a site where the story interrogates consent and control. Even if she experiences pleasure, Ari’s manipulation reveals how power habits can infiltrate intimacy, and his discomfort afterward suggests he recognizes the violation.

Charlotte is less a romantic character here and more a mirror held up to Ari: a proof that he can no longer pretend his gifts are separate from his ethics.

Dominique St. Clair

Dominique, called “Cleopatra,” is important precisely because philosophers are taboo targets. Her status marks the boundary the syndicates claim they will not cross, and Diamond’s decision to assassinate her signals that the war has moved into sacrilege territory.

Dominique’s presence as an Oxford-attending philosopher also reinforces how global and elite this world is—conferences, attributions, and reputations functioning like both scholarship and organized crime.

Even without extensive personal detail in the summary, Dominique’s role is weighty: she symbolizes the rare creators whose lives are consumed by the system’s hunger for perfection. The fact that philosophers die young and are treated as invaluable commodities makes her less an individual in syndicate eyes and more a resource, which is exactly the horror the story is highlighting.

Demeter

Demeter, also known as Dr. Amerson, is the character who most explicitly names the spiritual cost of alchemy. As an “alchiatrist” and former insider, she understands the gradual erosion that turns gifted people into empty instruments, and she speaks about it with the exhaustion of someone who has watched decay from the inside.

Her decision to save Sam is therefore a moral rupture: after a life of complicity, she performs an act of care that risks everything.

Her self-reflection exposes the story’s most unsettling idea—that cruelty can become routine even in someone who once wanted to heal. The detail that she tortured Will as a child during experiments underscores how systems normalize harm by calling it progress.

Demeter’s murder, swift and intimate, reinforces the underworld’s intolerance for redemption: the moment she tries to step out of the machine, the machine eliminates her.

Peter Taylor

Peter’s influence is largely posthumous, but it shapes the entire economy of the story. His discovery of the philosopher’s stone, and Diamond’s transformation of it into sand, establishes the central drug-metaphor of perfection: enhancement that looks like salvation while accelerating moral decay and death.

Peter is also part of Diamond’s emotional mythology—her remembered love, her imagined reunion—which suggests that the empire may have begun with genuine partnership or shared ambition before it hardened into predation.

He functions as a haunting absence: the origin point of the miracle that corrupted everything. In a narrative obsessed with transformation, Peter is the reminder that inventions outlive inventors, and that the ethics of a creation can be permanently warped by the hands that commercialize it.

Hayes

Hayes, the coworker killed in the Mandarin Palace explosion, represents collateral loss in the “ordinary” world before the syndicate war fully takes over Sam’s life. His death is a sudden, banal tragedy—gas leak, cigarette, disaster—that contrasts sharply with the later deliberate violence of alchemical executions.

That contrast matters because it changes the texture of Sam’s desperation: fate can ruin you randomly, but power can ruin you on purpose, and Sam’s turn toward alchemy is partly a refusal to remain at the mercy of accidents.

Eleanor Mien

Eleanor Mien, tied to Belle Epoque in Londinium, appears as the next face of the same enduring system. She represents continuity: even when Diamond dies and Grand Central collapses publicly, the infrastructure of ambition, vanity, and profit remains ready to be rebuilt under a new banner.

For Sam, Eleanor is both an opportunity and a trap—an invitation to regain belonging and influence, framed as a “position” rather than a sentence.

Her presence at the end sharpens the story’s final tension: the underworld doesn’t end; it changes management. Eleanor’s role suggests a more international, perhaps more refined iteration of the syndicate economy, where “perfection” can be packaged with new aesthetics while repeating the same moral emptiness.

Prometheus

Prometheus is the persona Rudra uses, and that persona matters because it reveals how recruitment works in this world: it begins with wonder. Turning dirt into an ice cream bar is not just a trick; it is an argument that reality can be rewritten, that a boy’s life can be rewritten, and that the rewrite will feel like destiny rather than coercion.

Prometheus, as a mask, embodies the story’s seductive lie—that transformation is always benevolent. The later exposure of Rudra’s control shows what the mask is designed to hide: transformation as ownership.

Themes

Perfection, transformation, and what it costs to want more

Sam’s earliest sense of transformation begins as something intimate and harmless: a cracked ceiling that still feels like a constellation, leftover meals that become a kind of magic through her mother’s skill, and the idea that a small life can still be full. When she witnesses matter change in front of her eyes, the meaning of “better” shifts from a daydream into a measurable possibility.

In Red City, alchemy isn’t presented as a cute fantasy upgrade; it is a system that turns longing into currency and then charges interest. The rules Ari learns—especially the boundary around souls—frame perfection as an asymptote: always approached, never reached, and never without consequences.

That creates a moral pressure cooker for both protagonists. Sam wants rest for her mother, safety for herself, and relief from the humiliations of scarcity, and those desires feel reasonable until they become the entry ticket into a world that monetizes human potential.

Ari’s training is also sold as advancement, yet it functions like a slow erasure: he excels while his family becomes distant, his language fades, and his sense of belonging gets traded for status and skill. The “sand” intensifies this theme by turning perfection into a product.

It sharpens gifts, appearance, and sensation, but it also narrows people into what they can produce for the syndicate. Diamond’s promise that Sam will never fear money again is true in the shallowest sense and corrosive in every deeper sense, because it replaces fear of bills with fear of disobedience and disposability.

When Sam realizes her achievements “weren’t free,” the story lands on an unsentimental insight: transformation can be real and still be predatory, especially when someone else controls the terms of your upgrade.

Wealth, class, and the trap of being “rescued”

Sam’s home life establishes a specific kind of poverty: not just low income, but constant calculation, the quiet dread behind every small accident, and the way a single event can collapse stability. The explosion that injures her mother turns struggle into a survival treadmill—medical costs, job rejections, the body itself becoming a barrier to employment.

That context makes Diamond’s world feel like an alternative universe, one where doors open silently, money appears without friction, and private fittings on Bond Street can be arranged like an everyday errand. Red City uses this contrast to show how wealth doesn’t merely purchase comfort; it rewrites what is considered normal, what is considered possible, and what is considered forgivable.

Sam’s entry into Grand Central is framed as opportunity, but the conditions reveal a familiar pattern: a powerful institution identifies talent in someone desperate enough to say yes, then names the arrangement “help” while building leverage. The weekly payments, the sudden deposits, and the luxury makeover are not generosity; they are tools that create dependence and complicity.

Sam’s mother’s injuries also highlight how class governs whose pain is treated as urgent and whose pain is treated as inconvenient. Her mother avoids bills by avoiding care, while Diamond treats bodies as modifiable assets within a private ecosystem of doctors, labs, and enforcers.

Ari’s experience mirrors this trap from another angle: he is “chosen” and placed in a lavish apartment, but his access to comfort is conditional on obedience, isolation, and the quiet severing of home ties. Even the elite students around him express class power through disdain, turning polish into a weapon.

The story’s sharpest point is that “rescue” offered by the rich often arrives as a contract you never fully read, because hunger and fear make fine print invisible.

Control through secrecy, surveillance, and curated truth

The hidden societies in Red City don’t survive by being stronger alone; they survive by managing information. The gold fox pins, the coded attributions, the rule against speaking to outsiders—these aren’t just aesthetic details.

They form an infrastructure that decides who gets to know reality and who must live in the fog. Ari’s intercepted letters are a clear example of how surveillance can be dressed up as guidance.

He believes he is studying for his family, yet the silence he receives is manufactured, and that manufactured silence reshapes him over years. He is not simply isolated; he is edited.

Sam experiences secrecy differently: she starts on the outside looking in, senses fear in her mother’s reaction, and then gets pulled inside because her memory is valuable. Once inside, secrecy becomes a leash.

She cannot speak freely, cannot confess to Ari, cannot even tell the truth about travel without risking punishment. The syndicates also show how control thrives on selective honesty.

Will explains alchemy and sand with enough candor to hook Sam but not enough to protect her. Diamond tells the truth when it strengthens her position and withholds truth when it would reduce her authority.

Even mentorship becomes an instrument: Diamond acknowledges Sam’s value only after Sam proves useful, and the praise is designed to bind. The Confession Rooms, the staged terror, and the casual disposal of bodies demonstrate that secrecy is enforced not only by rules but by spectacle—fear as a lesson for anyone tempted to step outside the script.

When Sam later involves the police, it’s not just a tactical move; it’s a rebellion against an information regime that depends on keeping outsiders blind and insiders complicit. Yet the ending complicates any clean victory, because Sam’s choice to return suggests that secrecy is also addictive: it offers belonging, status, and a clear identity in exchange for silence.

The story keeps asking a hard question without dressing it up: if someone controls what you know, how much of your life is actually yours?

Visibility, identity, and the violence of being seen the wrong way

Sam and Ari are built as emotional opposites in how the world registers them. Ari is noticed everywhere, and that constant attention doesn’t read as admiration; it reads as captivity.

He becomes a surface others project onto, and even his attractiveness is described like a spotlight he cannot switch off. Sam, meanwhile, moves through school as if she’s made of air.

Her invisibility is not a superpower; it is a social verdict that teaches her she can be overlooked even when she is brilliant. Their bond forms in the space between these experiences: Ari envies the quiet Sam inhabits, Sam envies the validation Ari cannot escape, and both misunderstand the other at first because they only see the fantasy version of what they lack.

Red City expands this theme through the practice of taking “attributions.” The idea of adopting the names of historical figures looks like a path to immortality, but it also suggests identity as costume, legacy as branding, and selfhood as something you can curate for power. Ari’s gradual loss of Gujarati is another form of identity violence—less dramatic than a beating, but similarly irreversible.

It shows how institutions can reshape a person without leaving obvious bruises, until home becomes a memory that no longer fits in the mouth. Sam’s identity shifts too, from dutiful daughter to secret apprentice to killer to witness, and each shift is forced faster than her body and mind can process.

Her obsessive handwashing after the murders reads as an attempt to restore a boundary between who she was and what she did, using skin as the last line of defense. The tragedy is that both protagonists are seen most intensely when they become useful—Ari as a talented alchemist, Sam as a rare mind—and that kind of visibility is conditional, transactional, and unsafe.

The story treats “being seen” as a need, but also as a threat, because the wrong gaze can turn a person into property.

Violence, moral injury, and how people learn to live with what they’ve done

The killings in Red City are not written as action set pieces meant to thrill; they function as turning points that change the texture of Sam’s inner life. Sebastian’s presence is crucial because he represents what happens when violence stops feeling like a decision and becomes a craft.

He speaks about killing like an aesthetic pursuit, which is horrifying not only because of the acts, but because of the calm certainty that this is a stable identity. Sam’s first deliberate kill is staged as an initiation that she does not want, yet feels forced to complete to survive and to prove she belongs.

Immediately afterward, the narrative tracks the consequences in her body: nausea, compulsive washing, loss of appetite, a mind that keeps replaying images it can’t file away. That is moral injury rather than simple guilt—the sense that something inside has been damaged at the level of meaning, not just emotion.

Diamond’s torture methods and the Confession Rooms show violence as governance. Pain is used to teach hierarchy, and mutilation is used to turn fear into loyalty.

The alchiatrist Demeter adds another layer by showing how caring professions can be corrupted when power offers a shortcut to mastery. Her reflections expose a slow numbing: the way repeated transgressions can make cruelty feel ordinary, then necessary, then invisible.

Even Ari’s use of bioalchemy during sex is part of this theme, because it shows how power can seep into intimate spaces and distort consent, attention, and self-respect. He is unsettled by himself, and that unsettled feeling matters because it marks the remaining boundary between him and the monsters around him.

The story also refuses to pretend that violence ends when someone escapes. Sam’s scars, including the stone-transmuted damage, are lasting evidence that the body keeps receipts.

The final temptation from Sebastian suggests the darkest truth the book offers: once you’ve been trained to survive in a violent system, peace can feel like exile, and returning can feel like the only place your altered self makes sense.

Love, loyalty, and the pain of choosing a side when every side is compromised

Sam and Ari’s relationship begins with small, human gestures—handwritten notes, curiosity, a shared sense that the world is stranger than it admits. That early tenderness matters because it becomes the emotional baseline against which later betrayals are measured.

When power enters their lives, their bond doesn’t disappear; it gets recruited. Lumines and Grand Central both treat affection as an access point, a way to reach leadership, gather intelligence, or capture a valuable person alive.

Ari is ordered to use nostalgia as a tool, and Sam is ordered to bring “Shakespeare” to Diamond, turning a private connection into a strategic asset. What makes this theme hit is that neither of them is lying about their feelings even when they are lying about their actions.

Their full-moon meetings on the beach show intimacy under threat: they arrive armed, test each other with questions, and still cannot let go. Loyalty becomes less about devotion and more about triage—who can you protect today without destroying them tomorrow.

Sam’s eventual decision to involve the police is not framed as purity; it is framed as necessity, desperation, and a bid to stop a machine that has already taken too much. Yet her later acceptance of Sebastian’s offer complicates the idea of redemption.

The claim that she will destroy the syndicate from within may be partly true, but it also reads as an admission that belonging has become tied to danger and influence. The most emotional loyalty in the book is not to a faction but to a person: Sam refusing to flee because Ari is imprisoned, and Ari walking toward Londinium because the story of his life no longer makes sense without her.

By the end of Red City, love is not a safe haven; it is a motive that keeps characters moving even when every step costs them something. The book’s bleakest tenderness is that devotion survives the systems designed to exploit it, but survival doesn’t guarantee innocence, and reunion doesn’t guarantee rescue.