Remain by Nicholas Sparks Summary, Characters and Themes

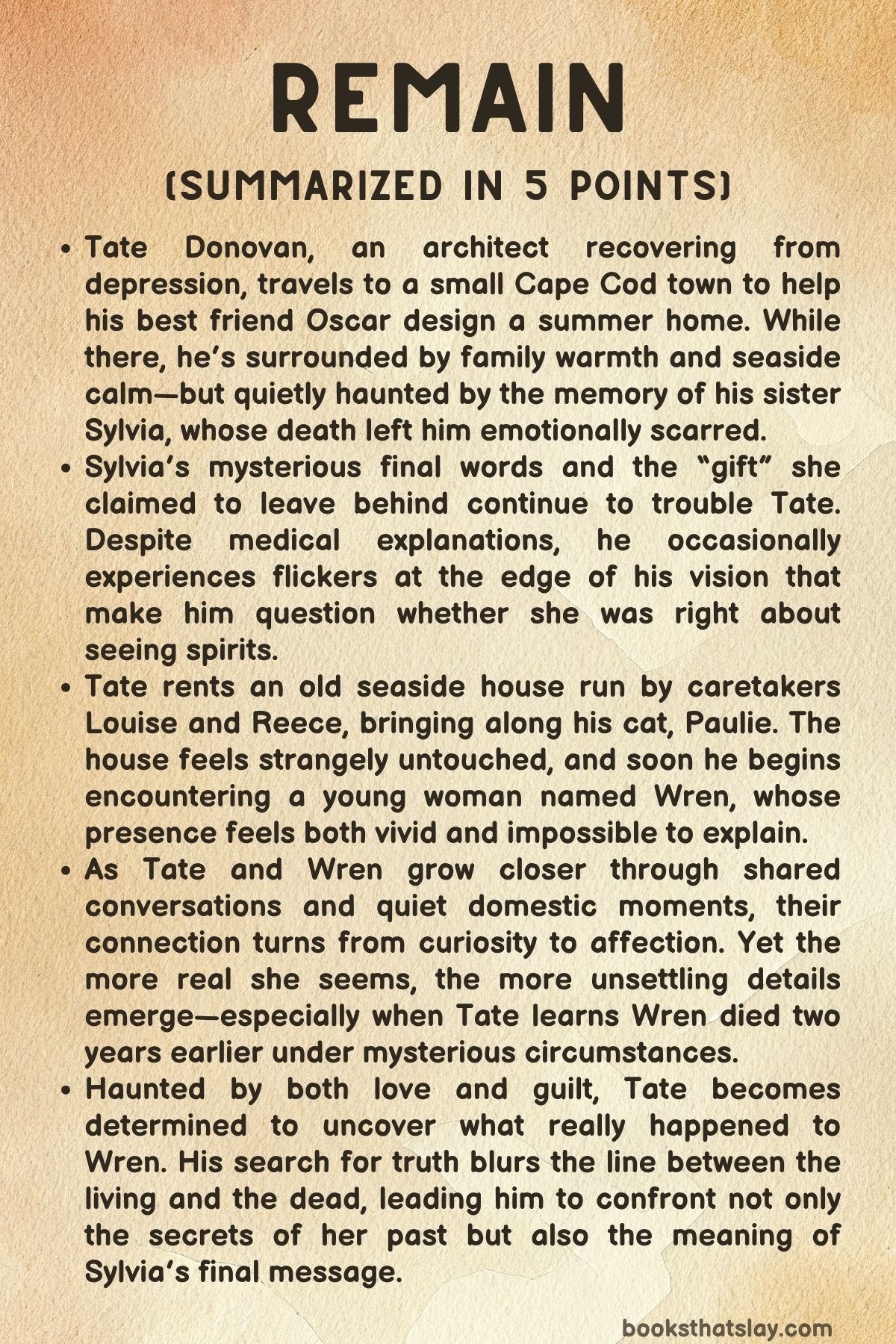

Remain by Nicholas Sparks and M. Night Shyamalan is a romantic mystery with a supernatural edge, centered on grief, second chances, and the idea that some unfinished stories refuse to end quietly. Architect Tate Donovan arrives in a Cape Cod town hoping for calm while helping his best friend design a summer home.

Instead, he’s drawn into an unsettling rented house, strange sightings he can’t explain, and a connection that feels impossible but real. As Tate faces his own fragile recovery, he’s forced to question what he believes about loss, love, and the boundaries between life and death.

Summary

Tate Donovan, a successful New York architect, drives to Heatherington on Cape Cod to help his lifelong friend Oscar plan a sprawling summer home for Oscar’s big, lively family. The town is busy with preparations for a music festival, and the coastal quiet seems like the kind of place Tate could finally breathe again.

Oscar, now a billionaire from a sports-jersey business, is thrilled Tate is there—but also watchful. Tate recently survived a serious collapse after the death of his sister Sylvia, and Oscar worries the darkness could return.

Tate’s grief runs deep because Sylvia was the one steady source of love in a childhood shaped by wealthy, distant parents. She grew up sick and often homebound, developing a rich inner world and a habit of noticing what others missed.

Tate left for boarding school and found real family warmth for the first time with Oscar’s immigrant household. As adults, Tate built a career on his own terms, while Sylvia created a gentle life with her husband, Mike, a music teacher.

Then Sylvia’s health failed again, and she died waiting for a heart transplant. Her death broke Tate open, and Oscar intervened to get him into psychiatric care, where therapy and medication helped him stand up again, even if he still felt unsteady.

Before Sylvia died, she told Tate unsettling things: that she saw spirits, that their parents had come to her, and that their mother had instructed her to breathe into Tate’s mouth as a kind of gift. Sylvia also promised that Tate would fall in love and that his life would change.

Tate tried to treat it as illness talking, yet he continued to experience brief flickers in his vision—moments that felt like movement just outside his focus.

In Heatherington, Tate rents a grand Victorian once run as a bed-and-breakfast. The caretakers, Louise and Reece Gaston, are friendly but tense, and they insist the place is empty and newly reopened for rentals.

Tate secretly brings his cat, Paulie. The house is beautiful, with ocean views and odd details, including a hallway bathroom door marked with a playful sign.

Almost immediately, Tate senses something off: faint humming when no one is there, a vivid nightmare of the bathroom door opening onto a cold, living darkness, and a growing feeling that the house is listening.

The next morning, Tate receives a video message Sylvia recorded before her death. In it, she tells him to talk to a stranger, to risk connection, and to remember that being needed can help a person heal.

Tate watches the video again and again, shaken by how alive Sylvia seems on the screen.

Soon after, Tate walks downstairs and finds a young woman calmly doing yoga in the parlor as if she belongs there. She’s direct, curious, and oddly unafraid of his tears.

When he admits what’s wrong, he ends up telling her everything: Sylvia, the breakdown, the hospital, the fear of sliding backward. The woman listens closely, then disappears in the span of a moment—vanishing while Louise is at the front door.

Tate searches the house, but every other room is locked, and Louise insists no one else is staying there.

The woman returns the next day, reappearing with new proof of presence: a large jigsaw puzzle set up under the dining table and a sweating glass of ice water. She introduces herself as Wren.

Tate tries to summon Louise and Reece as witnesses, but the instant they step inside, Wren and all evidence of her are gone. Alarmed, Reece reveals the truth Tate can hardly accept: Wren Tobin died almost two years earlier.

Tate frantically searches online and finds photos confirming it—Wren is the same woman he’s been speaking with, down to the clothes. Terrified that his mind is failing, he sets traps and records the hallway at night.

The bathroom door opens on its own. Water runs.

He hears a whisper for help and brutal impacts, but on video the figure he sees isn’t visible—only the sounds, the door, the faucet. Oscar watches the footage and urges Tate to leave, but Tate refuses.

If Sylvia’s final message was about reaching outward, then maybe this is what she meant. Tate decides he has to help Wren.

Wren begins appearing more often, though her image sometimes flickers, especially during storms. Tate grows attached to her fast, surprised by how easy it feels to talk to her.

They cook together, share wine, and trade stories about loneliness and fear. Wren admits she wants to sell the house and leave town, but she’s scared of what comes next.

She also tells Tate about Dax, a married counselor who became obsessed with her after she asked for advice, then stalked her when she rejected him. Tate, still haunted by his own past, understands the shame of being trapped in a story you can’t control.

Their bond turns romantic. After a playful “no-touching” challenge breaks down, Tate kisses her—and the power cuts out.

Wren vanishes. Later that night, Tate encounters a terrifying version of Wren in the bathroom: damaged, grieving, and locked into a violent loop.

In broken whispers, she insists she didn’t die by accident. She was murdered.

Tate and Oscar begin digging into Wren’s past, focusing on three men: Griffin, her ex-husband; Nash, a business partner with a history of betrayal; and Dax, the stalker. Tate meets Griffin and senses polish and performance.

Nash reacts with fury when confronted. Meanwhile, Tate’s determination makes him a target.

One night, he’s shoved down the cellar stairs and attacked by an unseen assailant. Injured, he refuses to back off.

During the music festival, Tate and Oscar work through alibis and pressure points. Tate also notices his old flickering visions intensifying, as if Wren is pulling him toward something specific.

He returns to the house and waits near the upstairs bathroom. Then he witnesses a replay of Wren’s final moments: an intruder wearing a smiling emoji mask attacks her, slamming her head into the faucet.

A second masked figure enters, helps stage the drowning, and steals Wren’s heart-shaped locket. Tate realizes two people were involved—and remembers seeing that same locket worn by Louise.

Before he can act, Tate is struck from behind by someone he recognizes and knocked unconscious. Wren, watching helplessly, senses the house is being set on fire.

Reece is deliberately fueling the flames. Oscar arrives and sees Wren at the window, signaling desperately.

As he tries to help, Louise rams him with a truck, then hits him again.

Inside, Wren urges Tate to wake. He revives and escapes the burning house, only to face Reece with a crowbar.

An explosion ends Reece’s attack, and Tate drags the badly injured Oscar away. Louise tries to finish the job, but police arrive in time to arrest her as the house collapses into ash.

Investigators confirm Reece started the fire and that both Reece and Louise had financial motives tied to Wren’s inheritance. Louise pleads guilty to attempted murder.

After recovery, Tate returns to the ruins and sees Wren one last time—calm, finally unburdened. They say goodbye, and she fades away.

Months later, Tate rebuilds his life, returns to work, and begins dating again. When he later sees the ghost of a child in snowy Central Park, leaving no footprints, Tate accepts that Sylvia’s “gift” is real: he can perceive those who remain, and he can help them find an ending.

Characters

Tate Donovan

Tate Donovan is the emotional and psychological center of REMAIN, portrayed as a deeply introspective man burdened by loss and an enduring sense of guilt. An architect from New York, he arrives in Heatherington seeking solace, but also unknowingly, a reckoning with his past and his fractured sense of self.

His character embodies grief, mental fragility, and redemption. Having suffered through depression and hospitalization following the death of his sister Sylvia, Tate’s world is colored by memory and melancholy.

His relationship with Sylvia defines him: her compassion and mysticism serve as both comfort and torment after her passing. Tate’s interactions with Wren become an extension of that emotional inheritance, forcing him to confront his fear of connection and his need for healing.

Through Wren’s ghostly presence, Tate evolves from a man paralyzed by grief into someone capable of embracing life again. The supernatural encounters he experiences are metaphors for his internal battles—between rationality and belief, detachment and empathy.

By the end of the novel, Tate’s journey is both spiritual and human: he accepts that love can transcend death, and that his purpose lies in using his “gift” to help others, mirroring Sylvia’s final wish for him to live and connect.

Wren Tobin

Wren Tobin is the haunting yet luminous figure who bridges the realms of life and death in REMAIN. Once a vibrant and determined woman burdened by personal losses and betrayals, she becomes the embodiment of unfinished business and restless love.

Wren’s life, marked by her grandmother’s death, failed ventures, and abusive relationships, is defined by independence shadowed by loneliness. Her posthumous existence reflects the turmoil of a spirit seeking truth and closure.

When Tate encounters her, Wren’s presence oscillates between warmth and fragility, revealing a ghost still tethered to pain, injustice, and longing. Her relationship with Tate transforms from eerie fascination to profound emotional intimacy—an unlikely love that transcends mortality.

Through their connection, she reclaims her humanity and confronts the trauma of her murder. Wren’s death, later revealed to be a calculated act of greed and betrayal, redefines her as both victim and guide.

Her eventual peace symbolizes acceptance and forgiveness, while her final farewell to Tate closes the loop between loss and healing. Wren is not merely a spectral figure; she represents the persistence of love and truth even beyond death.

Oscar

Oscar stands as the loyal, grounded counterpart to Tate’s instability in REMAIN. A self-made billionaire with an entrepreneurial spirit and a generous heart, Oscar represents friendship in its purest and most steadfast form.

His boisterous personality and devotion to his family contrast sharply with Tate’s introspection, making him both a foil and a stabilizing force. Oscar’s compassion extends beyond camaraderie—he becomes the guardian of Tate’s well-being, ensuring his friend doesn’t succumb again to despair.

His practical outlook and innate warmth humanize the narrative, anchoring the supernatural and emotional turbulence surrounding Tate. Yet, beneath his jovial surface lies quiet wisdom; Oscar understands pain and loyalty, and his willingness to risk his life during the story’s climax underscores his courage and moral integrity.

His near-death encounter at the hands of Louise further highlights his role as a symbol of unconditional friendship. Through Oscar, the novel celebrates the importance of human connection as the most tangible form of salvation.

Sylvia Donovan

Sylvia Donovan, though deceased for much of REMAIN, is a spectral presence whose influence shapes every major event. She is Tate’s sister, confidante, and moral compass—a figure of compassion, mysticism, and spiritual foresight.

In life, Sylvia’s illness confined her physically but awakened her inner vision, allowing her to perceive the unseen. Her belief in the afterlife and her calm acceptance of mortality make her both ethereal and deeply human.

Sylvia’s recorded messages to Tate form the emotional thread of the novel, serving as both guidance and prophecy. Her mysterious instruction to “breathe into Tate’s mouth” and the later manifestation of his supernatural sensitivity imply that she passed on a metaphysical gift—the ability to bridge worlds.

Through her, the novel explores the intersection of love, faith, and destiny. Sylvia’s wisdom enables Tate’s eventual transformation, as he learns to embrace both his grief and his gift.

In essence, she remains the book’s spiritual architect, shaping its emotional and thematic design long after her physical death.

Louise Gaston

Louise Gaston appears initially as a benign caretaker, polite and slightly wary, yet gradually evolves into one of REMAIN’s most chilling antagonists. Her character is a study in suppressed resentment and greed disguised as domestic decency.

Alongside her husband Reece, she manages the bed-and-breakfast where Tate stays, presenting an image of small-town reliability. However, as the narrative unfolds, Louise’s maternal façade crumbles, revealing jealousy, bitterness, and a willingness to commit murder for inheritance.

Her role in Wren’s death and later attempt to kill Tate and Oscar exposes the darkness festering beneath Heatherington’s tranquil surface. Louise’s duality—caretaker and killer—symbolizes the novel’s theme of deception and the hidden corruption within seemingly ordinary lives.

In contrast to Wren’s yearning for peace, Louise’s descent into violence underscores how unchecked greed can destroy both body and soul.

Reece Gaston

Reece Gaston complements Louise’s duplicity with a colder, more menacing presence. Initially portrayed as a gruff but harmless handyman, he is later revealed to be both complicit in and the executor of Wren’s murder.

His motivations—financial desperation and loyalty to Louise—expose a weak, easily manipulated man whose moral decay becomes literal when he burns the house to erase evidence. Reece’s act of arson, which ultimately leads to his death, symbolizes self-destruction born of guilt and cowardice.

Unlike Tate, who faces his inner ghosts, Reece runs from his, choosing denial until it consumes him. He embodies the novel’s darker reflection of human fragility—the capacity for evil when conscience gives way to greed.

Mike

Mike, Sylvia’s widower, is a figure of quiet strength and compassion, representing continuity and healing in REMAIN. His presence, though limited, is vital: he serves as a bridge between Tate’s past and present, offering stability and emotional grounding.

Mike’s role in delivering Sylvia’s recorded messages acts as a narrative catalyst, reigniting Tate’s journey toward closure. He symbolizes acceptance—the ability to honor love lost without being imprisoned by it.

Through Mike, the novel highlights resilience and the gentle endurance of those left behind, contrasting with Tate’s initial paralysis in grief.

Dax, Griffin, and Nash

These three men—Dax, Griffin, and Nash—form a trinity of suspicion surrounding Wren’s death, each embodying a different form of masculine failure. Dax, the manipulative counselor, represents obsession masked as concern; Griffin, the charming ex-husband, personifies deceit hidden behind charisma; and Nash, the bitter business partner, illustrates greed and betrayal.

Collectively, they serve as mirrors to Wren’s suffering and the toxic relationships that haunted her life. Each man, in some way, exploited or failed her, making them symbolic of the forces—control, manipulation, and exploitation—that trapped her both in life and after death.

Their eventual exoneration or exposure reinforces the story’s message that truth, though obscured by layers of deception, ultimately surfaces.

Paulie

Paulie, Tate’s cat, may seem minor but carries symbolic weight throughout REMAIN. As the one living being that connects Tate’s past, present, and supernatural encounters, Paulie represents innocence, grounding, and loyalty.

His instinctive reactions to unseen presences serve as subtle barometers of truth, reminding both Tate and the reader of the thin veil separating the natural from the supernatural. Paulie’s companionship softens Tate’s solitude, functioning almost as a silent guardian who senses what words cannot express.

Themes

Grief and Healing

In REMAIN, grief is not a passing emotional state but a living presence that shapes every decision and perception of the protagonist, Tate Donovan. His life after Sylvia’s death becomes a study in suspended time—where healing feels less like recovery and more like reorientation toward meaning.

Tate’s grief is compounded by guilt, loneliness, and the haunting echo of unfinished conversations. His sister’s final words—claiming connection with the afterlife and predicting his eventual transformation—linger as both comfort and curse.

The book situates grief as a process intertwined with love, suggesting that the depth of loss mirrors the depth of connection. Tate’s encounters with Wren’s ghost expand this theme, turning mourning into an act of communion across boundaries of life and death.

What begins as a psychological struggle becomes spiritual renewal, where accepting pain becomes the first step toward rediscovering purpose. By the end, Tate’s ability to perceive spirits is not treated as delusion but as evolution, implying that grief, when embraced, can lead to a heightened understanding of existence.

His love for Sylvia and later for Wren embodies the paradox of loss—that mourning can awaken one’s most vital capacities for empathy and care. The narrative ultimately frames grief not as something to escape but as a passage through which one learns to remain connected—to memory, to humanity, and to the mysterious continuity of love.

Love Beyond Life

The relationship between Tate and Wren forms the emotional center of REMAIN, exploring love that transcends physical boundaries. Their bond defies conventional definitions of intimacy, unfolding between a living man and a spirit caught between worlds.

This supernatural love story becomes a metaphor for the endurance of affection even after death, challenging the reader to consider the limits of connection. Tate’s growing attachment to Wren is as much about healing his own emptiness as it is about recognizing her unresolved anguish.

Their relationship reflects two incomplete souls—one haunted by loss, the other trapped by injustice—finding solace in each other’s presence. The narrative does not romanticize the impossibility of their love; rather, it uses it to explore the nature of emotional truth.

Love, in this context, becomes an act of recognition: seeing another being wholly, even when that being exists beyond ordinary perception. Their moments together—cooking, talking, laughing—offer glimpses of ordinary intimacy rendered extraordinary by their circumstances.

When Wren fades away after achieving peace, it reinforces that love’s purpose is not possession but liberation. Through loving Wren, Tate learns to love the living again.

By the closing scenes, love has become an energy that moves through time, bridging realities, proving that what remains after death is not emptiness but continuity of care, memory, and meaning.

Mental Health and Perception

REMAIN treats mental health with unusual tenderness, portraying Tate’s depression and visions not as simple symptoms but as thresholds between states of awareness. His hospitalization, therapy, and medication are part of his recovery, yet the narrative also questions what defines sanity in a world filled with unseen grief and invisible presences.

The flickers Tate perceives could be hallucinations or glimpses of another reality, and this ambiguity anchors the story’s tension. Nicholas Sparks and M. Night Shyamalan use this uncertainty to explore how trauma alters perception—how the mind’s sensitivity to pain can sometimes open doors to deeper understanding.

Tate’s journey mirrors the struggle many face when trying to reconcile rational treatment with experiences that defy clinical explanation. His visions of Wren might symbolize unresolved trauma, yet they also catalyze growth and moral awakening.

The story respects psychological realism while allowing for spiritual possibility, suggesting that what society labels as “madness” may, in certain contexts, be the psyche’s way of restoring coherence. Tate’s eventual acceptance of his ability to see spirits marks not regression into delusion but evolution toward wholeness.

The novel thus reframes mental fragility as a form of heightened empathy—a reminder that healing often requires acknowledging the truths that lie beyond reason.

Guilt, Redemption, and Responsibility

Throughout REMAIN, guilt operates as a force both destructive and redemptive. Tate carries guilt for Sylvia’s death, believing he failed her in her final moments.

This internalized blame shapes his isolation and fuels his obsessive need to help Wren’s spirit find peace. His quest to uncover the truth of her murder becomes a form of self-purification, a way to transform passive sorrow into moral action.

The novel suggests that redemption is earned not through denial of guilt but through responsibility—through acts that honor the lost by protecting the living. Oscar’s friendship plays a crucial role in this process, grounding Tate’s emotional turmoil in genuine care and accountability.

Wren, too, is haunted by her own guilt—over failed relationships, misplaced trust, and fear of moving on. When she reveals that her death was not an accident but a crime, her spirit’s restlessness mirrors Tate’s psychological entrapment.

Both must confront painful truths to be freed. By exposing Wren’s killers and surviving the inferno, Tate symbolically burns away his self-condemnation.

Redemption, in the novel’s moral universe, is not divine absolution but human persistence—the willingness to act despite despair. When Wren’s spirit finally departs, it signifies Tate’s rebirth as someone who can live without being defined by remorse, carrying forward the lessons of love, courage, and forgiveness.

The Intersection of Life, Death, and the Supernatural

The supernatural in REMAIN is less a genre device than an existential inquiry. The ghosts, visions, and inexplicable phenomena are treated as extensions of emotional reality—manifestations of what lingers when human lives end abruptly or unresolved.

The boundary between the living and the dead is portrayed as porous, maintained only by perception and acceptance. Through Wren and Sylvia, the story argues that death does not annihilate consciousness but transforms it.

The spirits who appear are not malevolent entities but echoes seeking acknowledgment and closure. Tate’s evolving ability to perceive them parallels his movement from denial to acceptance, from self-absorption to compassion.

The haunting of the house symbolizes humanity’s collective struggle with what it means to “remain”—to exist between remembering and forgetting, loss and renewal. By integrating ghostly presences into a deeply emotional human story, the novel redefines haunting as a metaphor for empathy: the act of recognizing another’s pain even when unseen.

The closing scene, where Tate sees a ghostly boy in Central Park, confirms this transformation. What once terrified him now calls to his compassion.

In embracing the supernatural as part of life’s continuum, Tate embodies the novel’s ultimate message—that love and consciousness are not extinguished by death, but continue, quietly, in the spaces where remembrance and mercy endure.