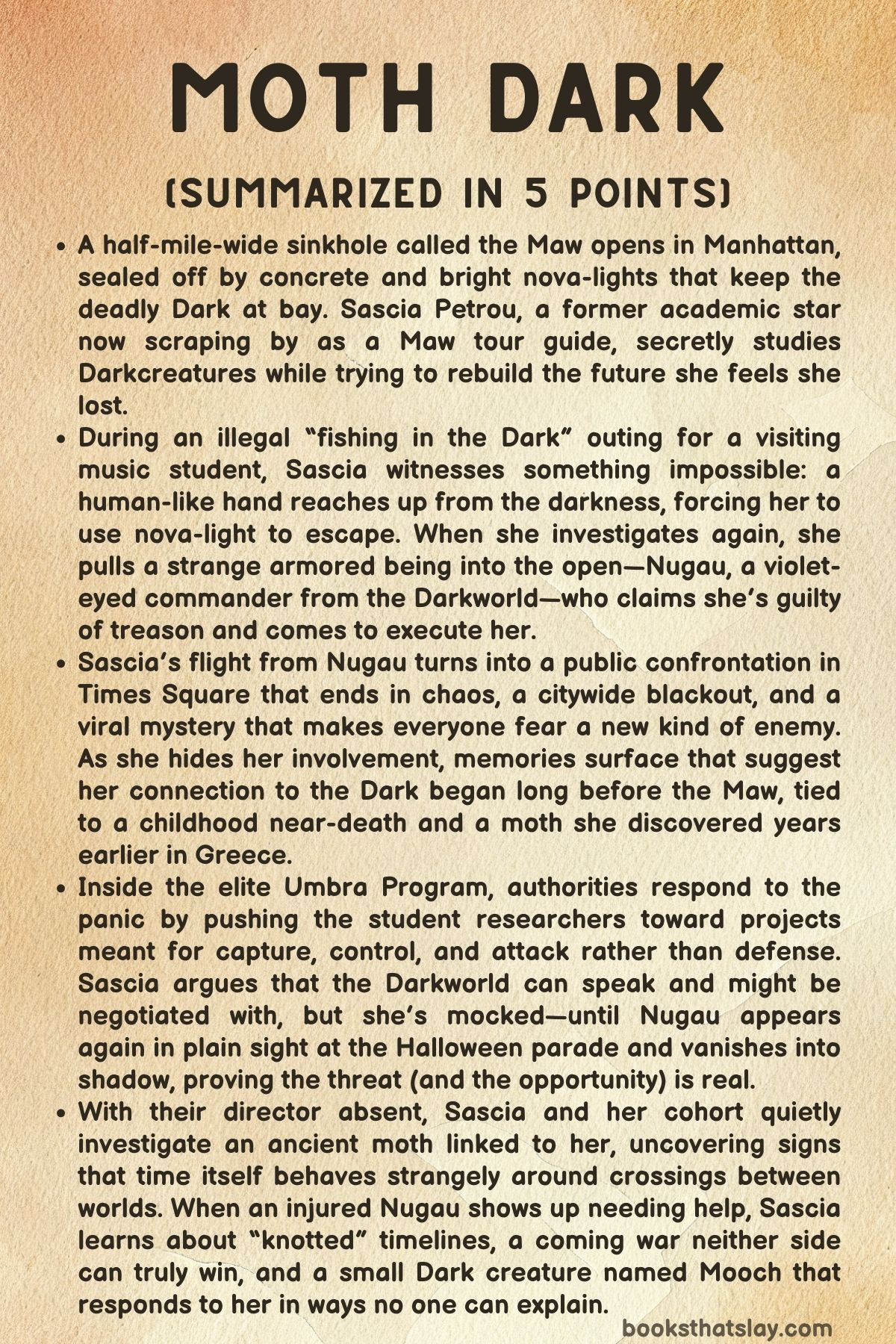

Moth Dark Summary, Characters and Themes

Moth Dark by Kika Hatzopoulou is a contemporary fantasy set in a New York City altered by the Maw, a half-mile sinkhole where a living darkness seeps into the world. Sascia Petrou, a former academic prodigy now scraping by as a tour guide, is obsessed with the Dark’s creatures and the strange moths she studies in secret.

When a violent encounter reveals a humanoid visitor from the other side, Sascia is pulled into a conflict between governments and a shadow realm called Itkalin—along with a dangerous discovery: time itself is tangled between the two worlds.

Summary

The Maw appears overnight in Manhattan, a vast pit of darkness so deep and strange it seems to swallow light. Authorities surround it with concrete and powerful nova-lights to hold back the Dark that leaks out.

Sascia Petrou makes her living guiding tourists around the barrier, explaining the disaster with practiced calm while privately fearing what might still be inside. Once, she was headed for a bright academic future; now she’s stuck in remedial classes, paying for them by selling stories about the very phenomenon that ruined her life.

After one tour, a Juilliard student named Yvonne asks Sascia for something illegal: a chance to “fish” in the Dark through small fissures in the city, catching harmless Darkcreatures as trophies. Sascia agrees for extra money and takes her to a hidden access point in a decommissioned sewer.

Using portable nova-lights and specialized gear, Sascia has Yvonne lower a baited line into the darkness, warning her that light kills most Dark life, so the lights must go out when something bites.

When the lights click off, bright Darkfireflies rise from the opening in brilliant colors. Yvonne captures a few, thrilled, while Sascia collects a sample for her own secret research.

Then something far worse happens: a gray-blue hand with a thumb grabs Sascia’s wrist from inside the Dark. She panics and fires her nova-gun into the hole, burning the hand away and killing the remaining fireflies.

Yvonne, thinking it was only a tentacle, leaves delighted with her jar. Sascia leaves shaken and calls her cousin Danny, a student in the elite Umbra Program that studies Dark phenomena.

He urges caution and pushes her to pick up a sonar device from Umbra to check for activity.

At Umbra, Sascia sneaks into her private lab and checks her prized Darkmoths—unusual insects that react to disturbances at their linked sites. One moth’s recording confirms something major occurred during her alley encounter.

Professor Carr, the program’s severe director, catches her working late and lectures her about her declining performance and wasted potential. Sascia hides what she saw, afraid Carr will exploit it.

That night, Sascia returns to the sewer access point with the sonar. Readings suggest nothing urgent, but her curiosity wins.

When she reaches into the opening again, moths swarm and a human-like touch meets her. She pulls a figure up from the darkness: a tall, violet-eyed humanoid in living, plant-like armor.

He calls himself Nugau, a prince and commander from Itkalin, and declares Sascia guilty of treason tied to something called the Battle of Feathers. He raises a crystal scythe to execute her.

Sascia escapes into the city with Nugau chasing her at impossible speed. Her nova-gun burns him, but he keeps coming.

In Times Square, police intervene. Bullets do nothing as Nugau summons a shield of solid shadow.

When authorities fire a powerful nova-light cannon, a surge of darkness blackouts the area, and Nugau vanishes. A viral video spreads, and New York erupts into fear, costumes, rumors, and demands for retaliation.

Umbra responds by shifting its research toward war. In a tense meeting, Carr announces orders from Chapter XI: countermeasures, nullification devices, and even offensive bioweapon projects.

Sascia argues that Nugau spoke English and might be reasoned with, and she suggests the Dark is closer to magic than biology. Carr mocks her and insists obedience.

The students comply outwardly, but unease grows as the world arms itself and begins burning and bombing Dark patches.

During the Halloween parade, Sascia notices an oversized moth—older and stranger than anything documented—appear again. It leads them to a costumed woman with violet eyes and cobalt markings who introduces herself as Nugau.

Sascia realizes this is not a prank: Nugau speaks as an outsider, calls humans “your people,” and recognizes Sascia’s moth as a god of Itkalin. Shadows gather on Nugau’s fingers, and in front of the group, Nugau slips into darkness and disappears.

Sascia finally admits to her cohort that the Times Square attacker was real and connected to her.

The students secretly regroup in Sascia’s lab to investigate. Genetic tests suggest the ancient moth predates known Darkcreatures, hinting at time anomalies in Dark biology.

Meanwhile, Sascia’s family life frays; relatives resent her choices, and old guilt surfaces about an accident that left Danny paralyzed.

One night, Nugau appears in Sascia’s bedroom badly injured, poisoned by a tar-like substance. Sascia treats them alone, guided by frantic moth behavior, and extracts a tar-coated moth lodged in Nugau’s throat.

As Nugau recovers, they explain “ymneen,” knotted time: travel between worlds tangles timelines, making encounters happen out of order. Nugau warns a war is coming that neither side can win, and insists separation is the only way to protect both worlds.

Sascia later finds herself in Itkalin, forming a fragile alliance with Nugau and their companions. She learns their leadership is earned through a Trial and a Claim, amplified by a force called the Thistha Ren.

Sascia also discovers she can “call” Mooch, a rift-making creature, not by command but by invitation—suggesting she has a deeper link to the Dark than she understood. Together they plan to prove that cooperation is possible and that the strange behavior of the itka moths points to a larger purpose behind the worlds’ connection.

Sascia trains for a public challenge in front of the Jagged Blade army and succeeds, earning growing respect—until the Queen arrives and forces a brutal test by trapping everyone in a shifting Labyrinth. Inside, betrayal and violence erupt.

Sascia fights to protect her allies, kills an attacker in close combat, and survives only with help, including human antibiotics retrieved at great risk. The experience hardens her resolve: answering every threat with force only feeds the cycle.

When Nugau attempts to present evidence and begin a Claim, the Queen unexpectedly yields the throne willingly, leaving motives unclear. Later, the conflict returns to the human side in a decisive raid: Sascia’s cohort, led by Crow’s hacking and a chaotic diversion using Darkrats and irritants, infiltrates a guarded compound.

They find Nugau chained inside a cage built from the same nova-light panel technology Sascia and Danny developed, with tubes draining black liquid from Nugau’s body. Professor Carr reveals the ambush was designed to lure Sascia.

He is building a permanent Darkgate and believes Sascia and her moths are the key.

Sascia pretends to comply, then uses Mooch to open a rift that brings Itkalin fighters into the facility. A battle erupts, livestreamed to the world.

Sascia releases swarms of itka moths to immobilize both sides and forces a ceasefire long enough to expose Carr’s deception and the time risks of tearing the worlds open. Nugau sends their forces back, then tries to pull all Dark from Earth into themself to end the threat.

Sascia stops them the only way she can, repeating a moment from their tangled timeline: she kisses Nugau while guiding Mooch into their mouth, triggering the “poison” incident that is revealed to be the cure that saves them and breaks the immediate crisis.

Afterward, public behavior shifts as people begin protecting wounded Dark life instead of destroying it. Chapter XI shuts down the Umbra Program, Carr is brought to trial, and leadership changes.

Sascia and her friends build a licensed sanctuary greenhouse for returning Dark flora and fauna. Beneath a growing Darksycamore, Sascia uses her new control to search the knotted timeline and pull different versions of Nugau into reach until she finds the one who recognizes her.

They share a brief moment together before Nugau returns to the Dark, headed toward a pivotal choice that will decide whether the loop continues—or whether everything unravels.

Characters

Sascia Petrou

Sascia is the story’s emotional and moral center in Moth Dark, defined by a life split between public performance and private obsession. Outwardly, she’s a hustling tour guide selling controlled fear around the Maw; inwardly, she’s still the academic prodigy who never stopped trying to understand the Dark on her own terms.

What makes her compelling is how her “failure” is both real and misleading: she did fall off the expected path, but she’s also doing the most original work in the narrative—quietly building a bridge between worlds when institutions only know how to build weapons. Her dread of the Maw isn’t simple terror; it’s intimacy with something that has shaped her identity since childhood, and that intimacy becomes agency once she accepts that she’s not merely adjacent to the Dark but entangled with it.

Sascia’s growth is a shift from secrecy as self-protection to truth as strategy: she learns that hiding information keeps her safe in the moment but feeds larger disasters, while speaking and acting openly can interrupt the cycle of escalation. Even when she fights, her defining trait is reluctance to reduce living beings to targets—her hesitation with the Ul’amoon and her later insistence on stopping the battle in the silo show a person trying to win without becoming what she fears.

The knotted timeline forces her into a rare kind of maturity: she has to live with versions of events where she is victim, aggressor, and rescuer, and still choose compassion without denying responsibility.

Nugau

Nugau is both antagonist and love interest at different points in the knotted timeline, which is exactly the point: they are not a single “type” of person but a moving consequence of war, duty, grief, and temporal dislocation. As a prince and commander, Nugau arrives with the terrifying clarity of someone trained to treat judgment as action; their first impulse is execution, not conversation, because they come from a culture where survival has likely depended on decisiveness.

But the story steadily reveals that this hardness is not innate cruelty—it is armor built from catastrophe, especially the long-term trauma of bombs, losses, and the cost of time slipping away. Nugau’s shifting behavior across encounters highlights how identity changes under different histories: an older, scarred Nugau carries the weight of choices already made, while a younger Nugau still has room for curiosity, flirting, and doubt.

Their core conflict is loyalty versus conscience, sharpened by their relationship to their mother and the throne; they could seize power, but the personal cost of turning against family and tradition keeps them suspended until events force a decision. Nugau’s tenderness is inseparable from danger—desire, hunger, and fascination blur at times, especially when they are injured and unguarded—yet that volatility reads as the human-like edge of someone who has never been allowed softness without consequences.

Ultimately, Nugau becomes a figure of reluctant leadership: they move from enforcing a verdict to trying to rewrite the rules that produce verdicts at all, even when doing so risks being seen as weak by their own people and exploitable by humans.

Danny Jacobs

Danny functions as Sascia’s anchor to ordinary affection and as the living reminder of the story’s costs. Their bond has childhood roots in shared curiosity—two kids studying something forbidden and wondrous—so Danny isn’t merely a sidekick; he’s the witness to Sascia’s earliest formation and the person who knows how long her obsession has been love rather than thrill-seeking.

The paralysis caused by the sewer accident is the most important emotional scar in Sascia’s life, and Danny carries it with a complicated mix of support and implicit grief: he continues to stand beside her while also embodying what her choices can break. As a researcher, Danny’s role is also thematic: he represents science with a conscience, someone who fears escalation and understands that knowledge can be turned into a cage.

His warnings are practical (sonar, safety) but also relational—he tries to keep Sascia alive without fully understanding how far the entanglement goes. When he joins the cohort’s covert resistance against Carr, Danny becomes a measure of trust: he is willing to risk himself again, which reframes the earlier accident from “Sascia ruined his life” into “their connection is resilient enough to keep choosing each other.” He ends up symbolizing the possibility of repairing harm without pretending it never happened.

Professor Carr

Carr is the story’s clearest portrait of institutional arrogance: a person who mistakes control for competence and obedience for morality. He views Sascia’s “lost potential” as a personal affront, which exposes how he treats students as assets to be optimized rather than people with agency and fear.

His scientific worldview is not simply rational; it’s possessive—he assumes the unknown exists to be captured, extracted, and weaponized, and he treats the Dark like a resource deposit rather than a living ecology. That mindset makes his pivot into bioweapons and permanent gate-building feel inevitable, not surprising: once fear and power become the guiding principles, every ethical boundary becomes “a necessary step.” Carr is also manipulative in a specifically academic way—he uses hierarchy, shame, and the promise of legitimacy to herd the cohort into complicity, then escalates into literal entrapment when persuasion isn’t enough.

What makes him chilling is that he believes he’s saving humanity; the story suggests his villainy is less sadism than certainty, the kind that can justify anything. His downfall is tied to exposure: the moment his methods are dragged into public view, the legitimacy he depends on begins to rot.

Tae-Suk Ho

Tae is a study in brilliance under pressure and what it means to be “the favorite” in a system that weaponizes talent. Positioned closest to Carr, Tae initially reads as an extension of the hierarchy, but the narrative gradually emphasizes that proximity to power is not the same as loyalty to it.

His work on nova-cannon designs becomes morally dangerous once repurposed, and Tae’s arc is shaped by the realization that invention is never neutral when authorities are hungry for tools. Unlike Sascia, who leads with instinct and empathy, Tae leads with precision: he wants clean solutions, controllable variables, and devices that function predictably.

That makes his eventual participation in sabotaging Carr especially significant, because it means he chooses uncertainty and risk over the false safety of compliance. Tae’s competence in the compound sequence also frames him as the cohort’s operational backbone—someone who can translate values into action without romanticizing the situation.

Crow

Crow represents the sharp edge of resistance: ethically messy, strategically necessary, and allergic to institutional permission. Their remote presence in meetings and later role in hacking and livestreaming positions them as a modern counter-power, someone who can puncture secrecy by turning it into spectacle.

Crow’s moral profile is complex because they weaponize information the way Carr weaponizes science; the difference is intent and target, but the method still carries harm potential. By orchestrating chaos (through hacks, diversions, and exposure) Crow shows that in a world sliding toward war, “clean” activism may be too slow.

The probation outcome—no internet devices—captures the story’s ambivalence about them: Crow helps stop a catastrophe, but the narrative refuses to crown them as purely heroic, implying that unchecked capability is dangerous even when used for good.

Andres Matthei

Andres is the cohort member most visibly pulled by the logic of preparedness and force, which makes him a key lens on how fear recruits otherwise thoughtful people. His willingness to pivot toward offensive applications doesn’t necessarily mean he enjoys violence; it suggests he believes the world will choose violence regardless, so survival depends on being ahead.

That pragmatism becomes a moral trap, because each “realistic” compromise feeds the machine Carr is building. Andres later contributes to Carr’s downfall through infiltration and information, which reframes him as someone capable of changing course when faced with undeniable evidence of abuse.

He embodies the story’s question of accountability: how much complicity comes from coercion, how much from belief, and how much can be redeemed through action once you understand what you’ve enabled.

Shivani Kaur

Shivani functions as a conscience-with-teeth: she worries openly about escalation and public panic, but she’s also willing to engage in uncomfortable tactics when the situation demands it. Her role in the compound plan—using Darkrats and biologically grotesque diversion—shows a character who understands that ethical purity can be a luxury during crisis.

That said, Shivani’s fear about nova-bombs and the public arming itself is one of the story’s most grounded warnings, because she sees how quickly “defense” becomes normalization of cruelty. She balances Sascia’s more personal, intimate connection to the Dark with a broader societal awareness: even if Sascia and Nugau solve their piece, the world can still choose hatred.

Shivani’s value to the narrative is that she refuses to let wonder erase consequences.

Boqin Shen

Shen is the story’s symbol of fragile, endangered diplomacy—the kind of leadership that tries to hold peace while being undermined by institutions built for war. Even mostly offstage, Shen’s influence is felt through what others say about them: they are the peace stance that governments and Chapter XI push against, suggesting that moral leadership often loses in the short term to fear-based policy.

Shen’s reinstatement at the end functions less as a triumphant return and more as a corrective after catastrophe: the story implies that peace wasn’t naïve, it was simply outgunned until the truth became too visible to ignore.

Yvonne Coleman-Zhao

Yvonne is a catalyst character whose brief presence reveals the story’s early ethical landscape. She arrives as a curious outsider, someone who wants an experience and a souvenir, and her Juilliard identity reinforces that she is tuned to spectacle and emotion rather than scientific caution.

Yvonne’s excitement at “fishing” in the Dark contrasts sharply with Sascia’s reverence and dread, highlighting how easily the Dark can be commodified by people who don’t live with its consequences. She also serves as a mirror for Sascia’s secrecy: Sascia can perform control and confidence for a client, but the moment the gray-blue hand appears, the performance shatters.

Yvonne leaving with a jar of fireflies captures an early theme that repeats later on a larger scale—humans taking pieces of the Dark without understanding what they’re provoking.

Mooch

Mooch is more than a pet-like companion; it is a living mechanism of fate, agency, and connection. On the surface, Mooch is a quirky, almost playful itka moth that steals snacks and opens rifts, but the story steadily reveals that its “help” is also authorship: it controls crossings, pulls people into moments, and effectively edits the order in which Sascia and Nugau meet.

That makes Mooch a character who blurs the line between creature and cosmic principle—an embodiment of the Dark’s agenda, or at least the Dark’s self-correcting logic. Sascia’s ability to “call” Mooch through invitation rather than command is crucial: it shows that true relationship across worlds can’t be built on control.

Mooch’s most striking trait is ambiguity; it saves and endangers in the same motion, forcing the characters to accept that the universe they’re in doesn’t care about clean narratives. In the end, Mooch becomes the hinge of mercy: the same “poison” incident that once looked like horror is reframed as the cure, suggesting Mooch engineers pain to prevent greater ruin.

Orran

Orran is the clearest expression of protective devotion within Itkalin’s side, a warrior whose competence is paired with caretaking. Training Sascia and trying to physically lift her out of danger positions Orran as someone who believes in decisive action, yet their loyalty isn’t blind; it’s rooted in the belief that Sascia matters to the future.

Orran’s injury in the Labyrinth, and their survival afterward, also makes them a symbol of how violence scars even the “best” defenders. They are a reminder that bravery often means absorbing damage so others can keep moving, and that such sacrifice doesn’t automatically make the world kinder.

Thalla

Thalla operates as strategist and stabilizer, using mist, stealth, and disciplined action rather than dramatic force. Their presence emphasizes that Itkalin’s people are not monolithic villains; they have members capable of restraint, planning, and loyalty grounded in something other than vengeance.

Thalla’s actions in both the Labyrinth and the compound confrontation show a character who can fight effectively without losing sight of objectives beyond bloodshed. In group dynamics, Thalla often feels like the person preventing emotion from collapsing into chaos, especially around Sascia’s human vulnerability and Nugau’s volatile leadership.

Ktren

Ktren embodies the factional cruelty that thrives in wartime—the kind of zeal that treats betrayal as a justification for any brutality. As a hunter in the Labyrinth, Ktren is not merely an opponent but a test designed to force Sascia into the very violence she wants to avoid.

Their attack and the intimate savagery of the fight, including the bite and the close-quarters struggle, makes Ktren feel like the physical manifestation of escalation: once the blade is drawn, there is no safe distance. Sascia killing Ktren becomes a moral wound that matters because it isn’t brushed aside; it sticks, raising the question of whether survival inevitably turns you into what you resist, or whether you can carry guilt and still choose a different future afterward.

The Queen of Itkalin

The Queen is power as environment: she doesn’t just rule, she reshapes reality around her, including the Labyrinth itself. Her leadership style is theatrical and coercive—forcing dance, forcing trials, forcing spectacle—suggesting a ruler who understands control through ritual and fear as much as through magic.

The non-hereditary Claim system adds complexity to her: she is not merely a queen by bloodline, but a victor amplified by Thistha Ren, which implies her authority is earned through violence and maintained through amplification. Her relationship with Nugau blends disappointment, blame, and possessiveness; she treats Nugau’s past absence as a betrayal of the realm, and she weaponizes that grievance to keep them in a state of guilt.

Even when she “yields” the throne, it reads as a strategic move rather than generosity, consistent with someone who sees people as pieces to position. The Queen’s role is central to the theme that war is often sustained by leaders who can’t imagine safety without dominance.

Ksenya

Ksenya’s role highlights the human cost of covert resistance: the person who agrees to be seen, grabbed, and mislabeled so the plan can work. Disguised as “the moth girl,” she becomes a deliberate decoy, which indicates both courage and a willingness to accept reputational damage for the group’s larger purpose.

Ksenya is important precisely because she is not framed as special by magic or destiny; her bravery is ordinary and tactical, the kind that makes large-scale heroics possible.

Sascia’s Parents

Sascia’s parents represent the gravitational pull of ordinary life—family labor, anniversaries, expectations, and the desire to believe a loved one can return to a safer path. Their restaurant is a grounding setting, a reminder that Sascia’s choices ripple outward into people who did not choose the Dark.

They are also part of the story’s tension around secrecy: Sascia’s silence protects them, but it also isolates her, making family scenes feel like both comfort and suffocation.

Aunt Rania

Aunt Rania embodies the voice of blame that often follows trauma, especially within families. Her anger at Sascia over Danny’s injury and squandered opportunities is harsh, but it also comes from a recognizable place: fear of repeating catastrophe and grief that never found resolution.

Rania’s function is to keep the narrative from romanticizing Sascia’s obsession; she insists on consequences and refuses to let “destiny” excuse harm. Even when she feels unfair, she forces the reader to sit with the reality that accidents can permanently alter lives, and that love doesn’t erase resentment.

Nan

Nan appears as a small but meaningful figure of human kindness inside a hostile cross-world context. By hiding and caring for Nugau when they were stranded, Nan becomes proof that compassion exists outside politics and without full understanding.

Her presence strengthens the story’s argument that “the other side” isn’t inherently monstrous; individual mercy can exist even when systems are built for fear.

Kilorn

Kilorn functions primarily as a wound in Nugau’s history—a named loss that turns abstract tragedy into personal grief. Mentioning Kilorn’s death anchors Nugau’s worldview in something that can’t be debated away: when you’ve lost someone to disasters tied to the world-linking conflict, the temptation to choose vengeance stops being theoretical.

Kilorn’s role is to explain, not justify, why war-thinking can feel like the only language left.

Themes

Fear, fascination, and the business of catastrophe

A half-mile-wide sinkhole in the middle of Manhattan does not stay a private horror for long. The Maw becomes a spectacle with barriers, nova-lights, and guided tours, turning an event that should reorder people’s sense of safety into something that can be narrated, priced, and consumed.

Sascia’s job puts her at the edge of that transformation: she sells controlled proximity to the unknown while her own body carries the cost of being near it. This tension makes fear feel transactional.

Tourists buy a story about darkness that can be safely framed by rules, equipment, and a confident guide voice. Sascia knows those rules are fragile, and the gap between performance and reality becomes part of her daily survival.

In Moth Dark, dread is not only an emotion; it becomes an economy, a social currency, and a way the city protects itself from having to sit with uncertainty.

That same dynamic spreads to the public response after the Times Square incident. A terrifying encounter is immediately turned into viral video, conspiracy theories, costumes, and arguments about whether the right response is peace or war.

The speed of that cultural conversion matters: it shows how communities often process threat by packaging it into something familiar—an outfit, a headline, a slogan—so it can be handled without changing anything deeper. The parade scene is especially sharp because it shows fear and entertainment sharing the same street.

People laugh about costume accuracy while the real figure stands right there, reminding the reader that public confidence can be built on misrecognition. The Maw’s darkness does not only distort light; it distorts perception, encouraging people to replace careful understanding with stories that feel satisfying.

Sascia’s private terror, by contrast, is messy and bodily: shaking hands, sleepless nights, a constant calculation of risk. That contrast highlights how catastrophe can be domesticated socially even while it remains wild and personal.

Knowledge as power and the ethics of research under command

The Umbra Program presents itself as a place of discovery, but the hierarchy in the meeting room reveals the hidden structure: prestige, obedience, and proximity to authority determine whose work matters and what kind of work is permitted. When Chapter XI orders reassignments, the research agenda pivots quickly from observation and defense to control and harm.

A genetic sample becomes a potential weapon. A moth garden becomes a trapping system.

A device meant to counter a blast becomes part of a broader escalation strategy. The speed of the shift is the point: in Moth Dark, the moral character of science is not guaranteed by intelligence, talent, or even good intentions.

It is shaped by who funds, who commands, and who benefits.

Professor Carr embodies the danger of treating curiosity as raw material for domination. He dismisses Sascia’s belief that the Dark might be magic, not because the claim is impossible, but because it threatens his model of expertise: if the world exceeds his framework, then he cannot control it, and control is what he wants.

The students’ dread is not only about the Dark; it is about what they are being asked to become. Their private “war room” is a quiet form of resistance, an attempt to reclaim research as understanding rather than manufacture.

Even that resistance is compromised, because their inventions are later used as prototypes in Nugau’s cage. The story refuses to let anyone off the hook easily: the cohort did not design a torture device, but their work becomes one when placed in Carr’s hands.

That chain forces a question that keeps returning across the plot: what responsibility does a researcher carry when their tools are repurposed?

The compound raid exposes the final shape of knowledge as leverage. Carr does not only weaponize Dark power; he weaponizes Sascia’s relationships by offering her friends and family as bargaining chips.

The scientific project becomes hostage-taking with a lab coat. Against that, the livestreaming twist matters because it shifts power from secrecy to exposure.

The same systems that encourage militarization also rely on control of narrative, and once the battle is visible, the institutional mask cracks. The shutdown of the Umbra Program at the end is not simply punishment; it is an admission that the structure was designed to turn wonder into coercion.

Secrecy, shame, and the struggle to own your story

Sascia’s life runs on concealment long before she meets Nugau. She hides academic derailment behind tour-guide patter, hides illegal excursions behind a professional face, and hides her moth research behind locked doors.

The secrecy is not framed as stylish mystery; it is framed as a survival strategy in a world that punishes deviation. Her history as a prodigy makes her “failure” feel like public property—something others are entitled to judge, correct, or exploit.

Carr’s disappointment is not just personal criticism; it is institutional shame, the kind that turns a person into a cautionary tale. That pressure helps explain why Sascia does not report the hand in the Dark or the truth about Nugau.

She expects that disclosure will not lead to support; it will lead to extraction.

Family scenes intensify this theme by showing that secrecy is not limited to labs. At the restaurant and the anniversary gathering, love and accusation share the same table.

Aunt Rania’s blame about Danny’s injury turns guilt into a family inheritance, something Sascia cannot set down even when she tries to rebuild her future. The narrative keeps returning to the idea that Sascia is “pretending” to live normally, and the bitterness in that word matters.

She is not merely lying to others; she is fighting to keep a coherent self-image when her life has been fractured by trauma, disappointment, and obsession. In Moth Dark, the damage of secrecy is double-edged: it isolates Sascia, but it also protects her from a system that would use the truth to control her.

When Nugau appears injured in her bedroom, Sascia’s refusal to call others looks like paranoia at first, but it also reads as a learned response to institutional predation. She chooses hands-on care, direct accountability, and private risk over handing the situation to authorities.

That choice is morally complicated, and the story treats it that way. Sascia’s secrecy can endanger people, yet openness can also become a weapon against her.

By the end, the arc does not suggest that honesty fixes everything. Instead, it suggests a narrower, harder victory: Sascia begins to decide when disclosure serves understanding and when it serves exploitation.

Owning your story becomes less about confessing and more about choosing the terms under which you are seen.

Othering, propaganda, and the politics of contact between worlds

A single figure in Times Square becomes a symbol onto which humanity projects every fear about invasion, contamination, and loss of control. People argue about peace versus war, but both sides often speak as if the other world is a single unified enemy.

The language around Nugau shows how quickly personhood can be stripped away. Sascia calls them an “elf prince” early on because she lacks vocabulary, and that label is not harmless; it packages a complex being into a costume category.

The public follows the same pattern at scale, converting the unknown into stereotypes that can be mocked, hunted, or rallied against. The Halloween parade scene becomes a mirror held up to that process: a crowd rehearses fear as entertainment while the real stakes sit inches away.

The aesin world has its own version of othering. Nugau refers to humans as “your people,” and the Itkalin leadership frames humans through the logic of treason, judgment, and collective guilt.

The “Battle of Feathers” accusation shows how one side’s internal history can become a death sentence for an outsider who does not even understand the charge. In Moth Dark, contact between worlds does not automatically produce empathy; it produces political narratives designed to justify violence.

The Queen’s insistence on separation is presented as strategy, but it also reads as ideology: a belief that safety requires strict boundaries and that crossing itself is a threat.

What pushes against this is the messy, practical work of relationship. Sascia and Nugau’s alliance is not based on abstract unity; it forms through injuries treated, truths exchanged, and risks taken in front of hostile witnesses.

The Heart Trial performed before the army becomes a staged argument for cooperation, using spectacle to counter spectacle. That matters because both worlds communicate through public rituals: rallies, trials, viral footage, military demonstrations.

The story suggests that politics is not only policy; it is performance, and whoever controls the performance controls the emotional logic of the crowd.

The ending sanctuary in Jackson Heights offers a different model of contact. Instead of framing Dark life as a military problem, the community begins shielding wounded creatures and dimming nova lights.

This is not portrayed as instant harmony; it is portrayed as a choice to resist reflexive dehumanization. The shift is small but meaningful: it replaces “enemy” with “wounded,” and that linguistic move changes what actions become possible.

Knotted time, memory across versions, and responsibility without certainty

Time in Moth Dark behaves less like a straight line and more like a set of entangled crossings that produce contradictory “first meetings.” Sascia encounters different versions of Nugau—scarred, younger, dying—and only later understands that these are not separate people but the same person arriving from different points. The effect is not a puzzle for puzzle’s sake.

It changes how blame works. If Nugau tries to execute Sascia in one moment but later depends on her care in another, then simple moral labels fail.

The story forces attention onto context: what did each version know, fear, and believe when they acted? This makes accountability harder but also more human, because real conflict often comes from partial information and misread intentions.

Mooch’s role adds another layer. The crossings are not random accidents; they seem guided by a being that can open slits in the Dark and decide who appears when.

That creates a tension between fate and agency. If Mooch controls timing, are Sascia and Nugau merely reacting inside a pre-set loop?

The narrative answers by showing that choices still matter inside constraints. Sascia chooses not to kill the chained Ul’amoon even when it would earn easy approval.

She chooses to reveal Carr’s deception publicly. Nugau chooses to attempt a Claim not as conquest but as an attempt to stop escalation.

These decisions do not erase the loop, but they change what the loop contains.

The reframing of the “poison” incident is one of the clearest thematic payoffs. An earlier moment that felt like grotesque contamination becomes, in another context, the mechanism of survival when Sascia guides Mooch into Nugau’s mouth during the final confrontation.

This reversal highlights how meaning depends on sequence and knowledge. The same act can be harm or rescue depending on when it happens and why.

That instability pushes the theme of responsibility: Sascia cannot control the larger structure of knotted time, but she can control her intent and her care in the moment she occupies.

The final image—Sascia searching the timeline to find the Nugau who recognizes her, while Nugau faces the choice of saving a drowning child—places moral weight on preserving a history that contains suffering because it also contains relationships, growth, and hard-won understanding. It turns time travel from fantasy escape into an ethical problem: if you can undo pain, what else do you erase, and who do you become afterward?

Leadership, legitimacy, and the danger of rule through amplified force

Power in Moth Dark appears in several forms—political authority, magical amplification, institutional command—and the story consistently asks how legitimacy is produced. In Itkalin, rulership is not hereditary; it requires a Claim and a Trial, and the Thistha Ren magnifies the victor’s power.

That system sounds merit-based on paper, but its emotional reality is brutal: Trials reward those who can survive public violence and command collective belief. The Queen’s dominance is therefore not only personal strength; it is strength made larger by a structure designed to escalate it.

When she traps everyone in the Labyrinth and declares the true Heart Trial has begun, she uses ritual as coercion, turning “tradition” into a weapon that forces compliance while claiming moral authority.

Nugau’s reluctance to challenge their mother highlights the difference between having capacity and seeking control. Their refusal is not framed as weakness; it is framed as a moral stance shaped by grief, loyalty, and fear of what power does to a person.

Sascia’s argument that courage can be nonviolent reframes leadership as restraint rather than conquest. That reframing becomes crucial later when Nugau tries to address the army with evidence and a plea to seek the itka’s true purpose.

They attempt to lead through persuasion instead of fear, and the Queen’s immediate move—freezing Nugau’s arm—shows how authoritarian leadership responds to nonviolent legitimacy: by disabling it.

On the human side, Chapter XI and Carr operate as a shadow version of the same theme. Carr’s authority in the Umbra Program depends on gatekeeping, mockery, and hierarchical control of careers.

His Darkgate project shows the final logic of illegitimate leadership: create a crisis, offer protection, and demand obedience. He even frames his coercion as necessary progress.

When his trap is exposed via livestream, legitimacy shifts because the public can see the gap between stated mission and actual behavior.

The ending does not claim that replacing one leader fixes everything. The Queen’s “willing” yield is presented as shocking precisely because it is ambiguous—an act that could be strategic surrender, manipulation, or a calculated attempt to control the narrative of defeat.

What matters thematically is that leadership is shown as something that can be challenged by collective witnessing. Whether in a throne room or a lab, rule becomes unstable when people recognize the performance behind it and refuse to keep clapping.

Violence, restraint, and breaking the reflex of escalation

Conflict in Moth Dark is immediate and physical—scythes, nova guns, soldiers, shadow shields—but the thematic weight falls on how quickly violence becomes automatic. The phrase Sascia later articulates to Nugau—when met with a blade, you answer with a blade—captures the trap both worlds are falling into.

The Umbra reassignments institutionalize that reflex by converting research into attack planning. Public panic does the same through nova-bombs, armed civilians, and political pressure against peaceful leadership.

On the aesin side, the treason charge and the army’s hunger for a Claim reduce complex problems into targets and punishments. The story treats escalation as a system, not a mood: once fear sets the rules, every side interprets restraint as vulnerability.

Against that current, Sascia’s defining resistance is not pacifism at all costs; it is a refusal to let violence become the only language available. She repeatedly insists on communication even when she is mocked, hunted, or injured.

Her compassion toward the chained Ul’amoon is a key moment because it interrupts the expected arc of “prove yourself by killing.” She recognizes suffering and captivity even in a monstrous body, and that recognition undermines the trial’s intended lesson. Later, when she releases the itka moths to pin both human and aesin fighters to the walls, she uses power to stop harm rather than to win.

It is force, but it is force used for disarmament, followed by explanation. The order matters: she creates safety first, then demands a different conversation.

Nugau’s arc runs parallel. Early versions of Nugau seek execution and revenge, but later they become committed to understanding the knotted time and preventing a war that cannot be won.

Their decision to attempt the Royal Claim is still a power play, yet it is framed as a tactic to remove amplified authority rather than to claim dominance for its own sake. Even the final choice to seal the rift by flinging Mooch into the Dark shows a willingness to sacrifice personal connection to prevent further slaughter.

The conclusion pushes the theme beyond battlefields. Ordinary people begin shielding wounded Dark creatures and smothering nova lights, shifting from “destroy the threat” to “reduce harm.” That is how escalation truly breaks: not with a single heroic speech, but with widespread refusal to keep treating fear as permission.

Desire, consent, and vulnerability as both risk and refuge

Bodies in Moth Dark are never abstract. Sascia’s injuries, exhaustion, and period are described as part of the plot’s reality, grounding high-stakes magic in lived physical experience.

That grounding shapes how intimacy appears: it is not an ornamental subplot, but a site where power and safety are negotiated. The Queen forcing Sascia and Nugau to dance the tarant—an intimate mating dance—turns sexuality into political theater.

The dance is coerced, watched, and intended to humiliate or bind, showing how authoritarian power often claims ownership over private experience. In that moment, intimacy is not comfort; it is surveillance.

At the same time, Sascia and Nugau’s growing closeness also becomes a form of refuge because it is one of the few spaces where honesty can exist without immediate exploitation. Their conversations about courage, separation, and fear carry emotional intimacy even before any physical act does.

When Nugau, semi-conscious and injured, asks Sascia to kiss them “one last time,” the request lands in an ethically unstable space—desire mixed with delirium, vulnerability mixed with danger. The story does not frame it as simple romance; it frames it as a moment where care, attraction, and boundaries collide.

Sascia’s choices repeatedly show awareness of risk: she refuses to involve others, but she also refuses to surrender her agency to Nugau’s intensity.

The climactic kiss in the silo is the sharpest expression of this theme because it is both emotional and tactical. Sascia kisses Nugau while guiding Mooch into Nugau’s mouth, using intimacy as a method to save Nugau and resolve a time knot that would otherwise kill them.

That combination could read as manipulation, but the narrative frames it as a desperate act of protection within a collapsing situation where consent, survival, and trust are tangled. The earlier “poison” incident is retroactively transformed by this act, showing how intimacy can carry consequences across timelines.

By the end, the brief reunion kiss after Sascia searches the knotted timeline feels earned not because it is triumphant, but because it is chosen. After so many scenes where institutions and monarchs try to control bodies—through cages, siphoning tubes, forced dances, and public trials—any mutual touch becomes an act of reclaiming personhood.

Coexistence, ecology, and the moral claim of nonhuman life

The Dark is not only a threat; it is an ecosystem full of creatures, plants, and behaviors that do not fit human categories. Sascia’s illegal “fishing” excursions expose the moral ambiguity at the heart of early contact.

On the surface, the activity looks like harmless adventure tourism—catching small creatures, collecting souvenirs, telling stories. But Sascia’s private research complicates it: the creatures are not props, and the Dark is not a theme park.

The rule that light kills Darkcreatures creates an immediate ethical tension because human safety relies on illumination that is lethal to the very life people are trying to understand. The accidental massacre of Darkfireflies after Sascia fires into the hole becomes a small tragedy that hints at a larger pattern: even defensive human actions can be ecologically devastating.

The Darkmoths are the clearest symbol of this theme because they are living instruments and living beings at once. They “mirror disturbances,” they swarm, they groom an ancient ancestor, and they guide Sascia’s attention during Nugau’s poisoning.

That guidance suggests intelligence or at least agency that deserves respect. The “Darknomaly” adds further weight by implying deep time and endurance, making the Dark ecosystem older and stranger than modern science can comfortably hold.

Once life is understood as ancient and meaningful on its own terms, treating it as raw material for weapons becomes harder to justify.

Carr’s siphoning of Nugau’s power and his attempt to create a permanent Darkgate represent ecological exploitation at industrial scale. He is not only hurting a person; he is attempting to force an entire world-connection into a machine-driven resource stream.

Nugau’s later act—pulling Dark from Earth into himself—flips the exploitation, but it risks mass death of Dark life under human light. Sascia stopping Nugau from ingesting more Dark shows that her ethics extend beyond allegiance to either side.

She is resisting the idea that ending conflict is worth ecological annihilation.

The sanctuary built in Jackson Heights is the thematic resolution: a deliberate space for Darkflora and Darkfauna to recover, nurtured rather than controlled. The change in human behavior—shielding wounded creatures and smothering nova lights—signals a shift from domination to caretaking.

Coexistence is presented as work: building infrastructure, changing habits, and accepting that safety may require learning to live beside difference instead of trying to erase it.