Some Kind of Famous Summary, Characters and Themes

Some Kind of Famous by Ava Wilder is a contemporary romance that explores the fragile balance between fame, family, and self-acceptance. At its heart, it follows Merritt Valentine, a former teenage pop star whose life has derailed after fame’s collapse.

Now in her thirties and living in the shadow of her successful twin sister Olivia in a small Colorado town, Merritt grapples with rebuilding her identity away from the spotlight. When she meets Niko Petrakis, a gentle, artistic handyman, their growing connection challenges both to confront past wounds and rediscover creativity, trust, and love. The novel blends humor, warmth, and emotional complexity in a story about second chances and belonging.

Summary

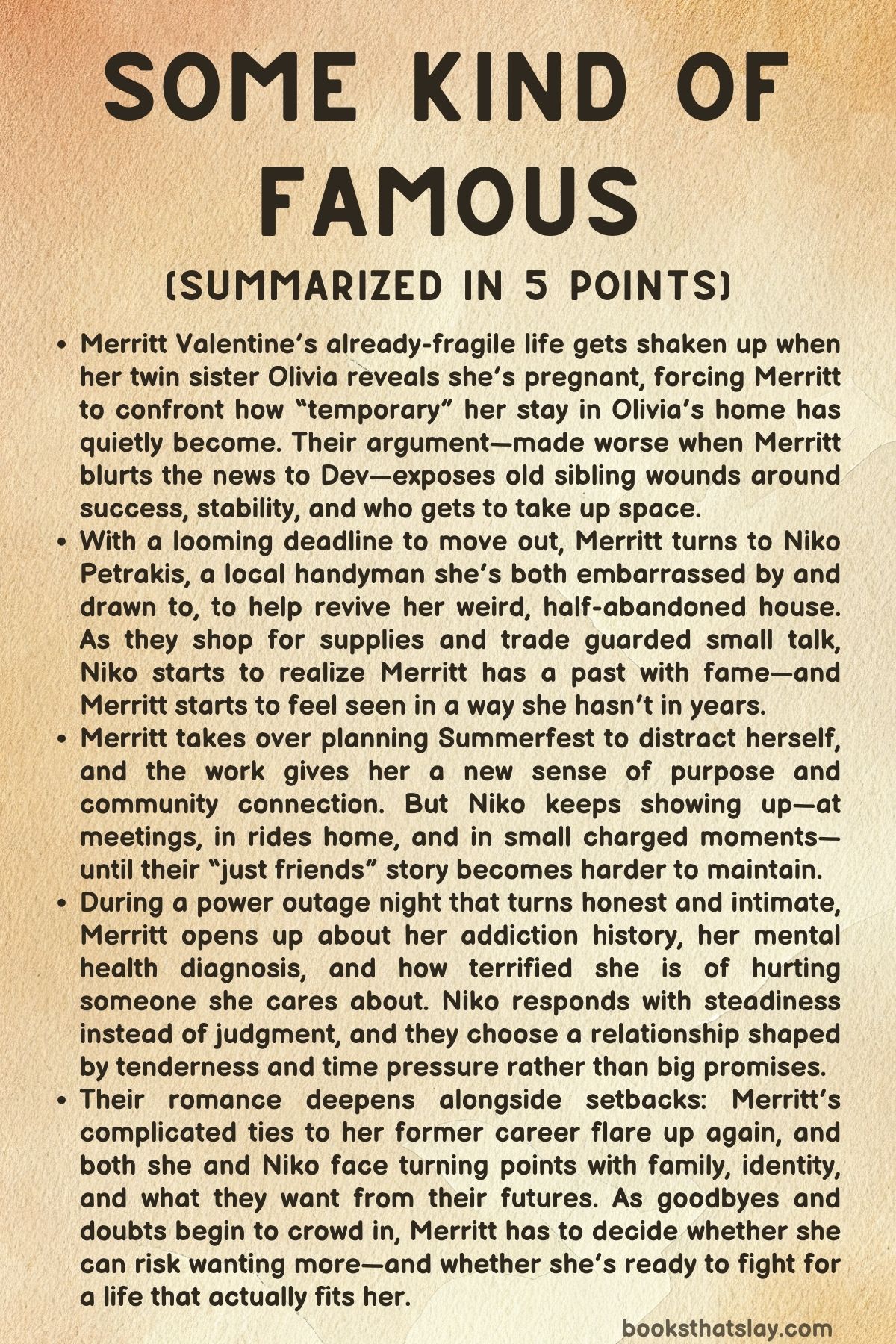

Merritt Valentine’s life is at a crossroads. Once a famous teenage musician, she’s now living with her twin sister Olivia and Olivia’s husband, Dev, in the quiet Colorado town of Crested Peak.

What was meant to be a temporary stay has stretched into two years of inertia, her fixer-upper house standing neglected while she tries to rebuild her life after a failed career and heartbreak. The fragile calm breaks when Olivia arrives one evening visibly anxious, revealing that she’s pregnant.

Though Merritt wants to be happy for her, she’s unsettled by the realization that Olivia’s next chapter means she’ll have to move out.

Their conversation soon becomes tense. Olivia admits she removed her birth control without telling anyone, and that Dev plans to turn Merritt’s room into his office.

Hurt and defensive, Merritt blurts out Olivia’s pregnancy before her sister can share the news herself. The fallout leaves both feeling guilty, but later that night, they reconcile on the porch.

Olivia reveals she’s having twins, and they talk about their late father, whose absence still lingers. She suggests Merritt call Niko Petrakis, a handyman and friend, to finally start working on her long-abandoned house.

Merritt is reluctant—she’s embarrassed by an earlier awkward encounter with him—but agrees to reach out.

From Niko’s perspective, Merritt’s home—nicknamed “The Mollusk”—is a quirky architectural mess, yet he finds her intensity fascinating. Though she’s guarded, he senses her loneliness.

When he jokingly compares the house’s timeline to a pregnancy, she accidentally reveals Olivia’s secret again, realizing how easily she slips. Niko, amused and intrigued, invites her to join him on a supply run to Silverton.

During the trip, their chemistry grows. They bond over music and art, though Merritt remains wary of intimacy and recognition.

When a flea market vendor recognizes her, Niko senses a deeper story behind her fame but chooses not to pry.

Their dynamic continues to evolve through casual encounters around town. Merritt, self-conscious about her past and afraid of new beginnings, finds herself drawn to Niko’s quiet steadiness.

Olivia, protective of her sister’s fragile recovery, warns Merritt not to play with his emotions. Trying to prove her responsibility, Merritt volunteers to help organize the town’s Summerfest, finding a small sense of purpose again.

At the festival planning meetings, Merritt suggests a humorous “Mr. Crested Peak” pageant that unexpectedly becomes the event’s main attraction. When Niko arrives late and sits beside her, their mutual attraction deepens.

He later offers her a ride home, and their conversation is charged with unspoken feelings. Despite promising herself not to get involved, Merritt can’t help thinking about him.

As Niko continues renovating her house, they share more moments of connection. He invites her to see his furniture workshop, and their visit turns unexpectedly intimate when she discovers his art—including a nude self-portrait.

Though flustered, she compliments his work, and their tension grows. Their friends notice the spark between them, teasing both relentlessly.

Still, they avoid acting on it, caught between desire and hesitation.

Meanwhile, Merritt’s old publicist reaches out, suggesting a collaboration that could revive her music career. The thought dredges up painful memories of addiction, public scrutiny, and the breakdown that ended her fame.

She pushes the idea aside, focusing on her friendship with Niko. During their time collecting donations for the festival auction, their bond deepens through laughter and small talk.

Later that night at the local bar, their playful banter gives way to something tender and raw. When the band recognizes her from her pop-star days, she endures the attention gracefully, realizing she’s no longer defined by it.

As the weeks pass, Merritt struggles with conflicting emotions—her growing love for Niko and her fear of repeating old mistakes. Their friendship eventually turns romantic after a power outage leaves them alone together at her house.

They talk honestly for the first time, sharing secrets and pain. Merritt opens up about her overdose, her diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, and her constant fear of losing control.

Niko responds with compassion, revealing his own complicated family history and quiet insecurities. Their vulnerability draws them closer, and they finally give in to their attraction.

Their relationship begins gently, with both finding comfort in each other’s presence.

The following weeks are filled with small joys—lazy mornings, music, laughter, and love that feels real. Niko’s calm balances Merritt’s intensity, and she rediscovers her creativity, writing songs again.

But beneath their happiness, the expiration date of their summer looms. Niko’s rental home is being sold, and he plans to move away.

When an argument about her ex-boyfriend breaks out, they make love in an attempt to mend the rift, but Merritt dissociates during the act. The episode exposes the fragility beneath their connection.

Niko reassures her tenderly, but afterward, both are forced to confront that love alone may not heal everything.

As summer ends, Niko prepares to leave town. Merritt helps him pack and attends his farewell party, hiding her heartbreak behind a brave face.

They spend one last night together, and when she wakes the next morning, he’s gone. Alone in her empty house, she finds a mural he painted across her wall—a vivid map of Crested Peak filled with their memories.

The gesture devastates and comforts her in equal measure.

Trying to move forward, Merritt throws herself into Olivia’s baby shower. When she realizes she’s missed her period, she quietly takes a pregnancy test.

Olivia discovers it, and they erupt into a painful argument that unearths old wounds from Merritt’s overdose years earlier. The sisters finally speak honestly, grieving the trauma that scarred them both.

When the test turns positive, they embrace, reconciling fully.

Meanwhile, Niko settles in Arizona with his family, missing Merritt but finding solace in his art. His paintings unexpectedly gain attention, signaling a new chapter.

He reconnects with his mother and comes out as bisexual, feeling more at peace than ever.

Back in Colorado, Merritt learns that her pregnancy was a brief miscarriage. The loss stirs complex emotions, but it also brings clarity.

Talking with Olivia, she realizes how much she’s grown and that she truly loves Niko. Deciding to fight for him, she takes it as a sign when her tarot reading reveals the Two of Cups—partnership and reunion.

At the same time, Niko hears that Merritt had bought a pregnancy test and rushes back, terrified she might need him. But when he arrives at her house after hours of driving, she’s gone—because she’s already flown to Greece to find him.

Their miscommunication ends in laughter over the phone as they confess their love. Merritt assures him she’s no longer pregnant, but that she still wants a life with him.

They agree to reunite.

Meeting again in Athens, they fall into each other’s arms. They talk openly about their fears and plans, reaffirming that their love is worth the risk.

Niko takes her to his grandmother’s village, where she meets his family and witnesses the joy he’d long been missing. Their time together in Greece cements their bond and marks a new beginning.

A year later, Merritt and Niko are thriving back in Crested Peak. She’s returned to music, recording new songs in the studio he built for her, while he’s become a respected artist and town council member.

They live surrounded by friends, family, and a shared sense of peace. In the novel’s closing moments, they rest together in their hammock, their matching tattoos symbolizing unity and resilience.

Merritt feels content at last—famous not for her past, but for the love and life she’s built anew.

Characters

Merritt Valentine

Merritt Valentine stands at the emotional core of Some Kind of Famous, a woman navigating the wreckage of fame, failed love, and the search for self-acceptance. Once a teenage pop sensation, she now lives in quiet exile, battling the weight of her past and her diagnosis of borderline personality disorder.

Her relationship with music reflects her fractured identity—something that once gave her power but also consumed her. Merritt’s decision to rebuild her abandoned house mirrors her internal restoration, a literal reconstruction of a life she thought had fallen apart.

Her relationship with Niko becomes a catalyst for healing: through his quiet empathy, she learns that vulnerability can coexist with strength. Merritt’s arc is one of redemption, as she moves from shame and isolation to creative rebirth and emotional intimacy.

By the end, she’s not just a survivor of her own story but its author, reclaiming the music, love, and sense of self that fame had stolen from her.

Olivia Valentine

Olivia serves as Merritt’s foil—organized, accomplished, and seemingly in control, yet carrying her own insecurities. As the “responsible” twin, she’s built a life defined by stability: a PhD, a husband, a home.

However, her pregnancy forces her to confront both her dependence on control and her emotional distance from her sister. Beneath her polished exterior lies deep fear—fear of losing the family dynamic she’s known and of Merritt slipping back into self-destruction.

Their volatile yet loving relationship underscores the novel’s themes of sisterhood and forgiveness. When Olivia finally admits the fear and guilt she felt during Merritt’s breakdown, her character transforms from judgmental caretaker to compassionate equal.

By the end, she evolves into a figure of empathy and renewal, her motherhood symbolizing both literal and emotional rebirth for their family.

Niko Petrakis

Niko represents grounded warmth and quiet resilience in contrast to Merritt’s chaos. A Greek-American handyman and artist, he embodies authenticity—someone who has also wrestled with displacement, abandonment, and identity.

Niko’s artistic sensibility mirrors Merritt’s, but his expression is tactile and unpretentious, anchored in creation rather than performance. His relationship with Merritt allows him to explore his own fears of vulnerability; his compassion becomes transformative for them both.

Through him, the novel challenges the notion that love must be dramatic or destructive—it can be gentle, healing, and profoundly human. His bisexuality, revealed later in the story, reinforces his openness and honesty, qualities that become central to his bond with Merritt.

Niko’s evolution from a quiet handyman to a successful artist and partner shows how love, when mutual and transparent, nurtures growth rather than consuming it.

Dev

Dev, Olivia’s husband, operates on the periphery yet plays an important role in highlighting Merritt’s feelings of displacement. He represents the stability Merritt both envies and resents—a man with a steady career and a clear place within Olivia’s world.

His discomfort around Merritt and Niko’s connection exposes the quiet fractures within the seemingly perfect domestic sphere. Though not unkind, Dev’s character reflects the subtle tension between duty and affection; he is a man who means well but struggles to navigate emotional complexity.

His presence grounds Olivia’s story while simultaneously serving as a mirror for Merritt’s alienation, underscoring how family can feel both safe and suffocating.

Alan

Alan embodies Merritt’s old life—one defined by emotional distance disguised as passion. Their long-distance, largely virtual affair reflects her avoidance of genuine connection.

He is a man drawn to the idea of Merritt rather than the person, serving as a symbol of her self-sabotaging tendencies. Through their disengagement, Merritt recognizes how much she’s been living in emotional limbo, clinging to the comfort of being wanted without risking being truly known.

Alan’s presence fades as Niko’s grows, marking the shift from hollow validation to authentic intimacy.

Freya, Pam, Simon, and Jo

Freya and Pam provide the grounding presence of small-town community—women who draw Merritt back into the rhythm of ordinary life through the Summerfest committee. They represent acceptance without pretense, offering her a sense of belonging that fame never did.

Simon and Jo, Niko’s roommates, add levity and warmth to the story, humanizing both Merritt and Niko by anchoring them in friendship. Jo’s admiration for Merritt as a fan transforms into genuine respect, showing how fame can evolve from a barrier into a bridge once real humanity is seen beneath it.

Themes

Identity after fame and the right to be ordinary

Merritt’s relationship with fame is not framed as a glamorous backstory but as an ongoing wound that affects how she moves through rooms, how she interprets attention, and how she protects herself from being “seen” in ways she can’t control. In Some Kind of Famous, recognition functions like a spotlight she can’t switch off: strangers know her face, yet they keep a careful distance, as if her past celebrity makes her less approachable and more fragile at the same time.

That social hesitation mirrors Merritt’s own internal split between the person the public once consumed and the person she is trying to become. Her refusal to talk about why she stopped making music reads less like mystery and more like self-preservation; she has learned that explanations invite judgment, and judgment can become a trigger.

This theme gains weight through contrast: Olivia’s identity looks stable and legible to others—degree, marriage, house, career—while Merritt’s looks like an unfinished sentence. The town, with its routines and committees and small businesses, becomes a testing ground for whether Merritt can belong without performing.

Even her house, with its strange architecture and abandonment, symbolizes the problem: a structure that exists, but doesn’t yet feel inhabitable. Niko’s presence presses gently against Merritt’s defenses because he wants to know her without consuming her; he resists researching her story and instead chooses earned intimacy over curated myth.

That choice matters because it gives Merritt a model for how her history can be acknowledged without becoming the only thing that defines her. The arc suggests that “moving on” is not the point—what matters is reclaiming authorship.

Merritt’s return to music at the end is meaningful precisely because it isn’t a return to the old machine of fame; it’s a return to her own voice, on terms she sets, in a life where being ordinary is not failure but freedom.

Sibling intimacy, resentment, and the shifting balance of care

The sisterhood at the center of Some Kind of Famous is built from love, competition, and the quiet accounting that happens when two people share a childhood but not the same adulthood. Olivia and Merritt know each other’s tells, history, and vulnerabilities, which makes their conflict sharper: the person most capable of hurting you is often the one who understands exactly where it will land.

Olivia’s pregnancy forces the question that Merritt has avoided for two years—whether her stay in the family home is refuge or stagnation—and the practical consequence (losing her room) lands as an emotional verdict: you’re no longer allowed to pause. Merritt’s anger is not simply about space; it’s about being repositioned as a temporary problem to solve, especially by a sister whose life appears organized and socially approved.

At the same time, Olivia’s frustration is not only about logistics; it carries the exhaustion of being the “responsible one” who has had to worry in the past that Merritt might not survive herself. When Olivia reveals she was terrified after Merritt’s suicide attempt, the dynamic clarifies: underneath the judgment is fear, and underneath Merritt’s defensiveness is shame and grief about the damage her pain caused.

Their reconciliation is not a clean reset but a renegotiation of roles. Olivia tries to protect Niko from Merritt, implying Merritt is inherently dangerous in love, and Merritt takes that warning in because she half-believes it.

Yet later, Olivia also admits she was wrong to reduce her sister to a risk profile. The theme insists that sibling love is not always soft; sometimes it is controlling, sometimes it is resentful, and sometimes it is the only force that makes honesty possible.

The twin detail intensifies this because twins invite constant comparison: Merritt’s stalled career and Olivia’s stability become a living scoreboard neither asked for. What changes across the story is their willingness to see each other as separate adults rather than opposing halves of a single narrative.

By the end, the sisters are not magically harmonious; they are more truthful. That truth includes apology, accountability, and the recognition that caretaking can become a trap if it replaces respect.

Mental health, trauma, and the work of staying alive

Merritt’s mental health is not treated as a twist or a label for drama; it is shown as a daily reality that shapes memory, desire, and decision-making. Her history with addiction and overdose clarifies that the danger was not abstract—her body has already come close to not being here.

The disclosure of borderline personality disorder is handled in a way that emphasizes patterns rather than stereotypes: impulsivity, fear of abandonment, and intensity in relationships appear as experiences Merritt understands and fears, not as a moral failing. When she tells Niko she becomes “obsessed,” it is both honesty and warning, and the tension of the romance comes partly from whether love can survive the pressure of that intensity without turning into harm.

The dissociation scene in the pool and afterward marks a critical truth: even in wanted intimacy, the nervous system can revolt. Merritt’s grounding with ice is not romanticized; it’s practical, learned, and a little lonely because it exposes how private her coping has been.

Niko’s response matters here: he does not punish her for needing to stop, and he does not demand an explanation that turns her body into a courtroom. That reaction models a form of care that is neither pity nor control.

Still, the story doesn’t suggest that one supportive partner fixes everything. Merritt remains afraid of what she can do to someone she loves, and Niko carries his own tenderness and insecurity, including the ache of loving someone who might leave emotionally to protect herself.

The theme also explores how public life can intensify trauma. Merritt describes how painful it was to give so much of herself to strangers, which suggests that her breakdown wasn’t only personal weakness; it was also a product of constant exposure and expectation.

Healing, then, is shown as relational and structural: therapy is named, boundaries are practiced, and Merritt learns that being honest about her needs is not the same as being “too much.” The ending doesn’t erase her diagnosis; instead, it frames stability as something built—through routines, honest conversations, creative work, and a partnership that treats mental health as part of life rather than a reason to withdraw from it.

Creativity as vulnerability and as a path back to agency

Creative work in Some Kind of Famous is tied to identity, but also to risk: making art means being seen, and being seen has hurt both leads. Merritt’s music history shows creativity as exposure—her voice and image once belonged to an industry and an audience that expected endless access.

Her refusal to return to music is not laziness; it is a protective boundary against a version of creativity that required self-erasure. Niko’s art offers a parallel in a quieter key.

He paints for himself and avoids formal study because he fears that external validation would change the relationship between him and his work. That fear is not irrational; it’s a recognition that once art becomes a product, it can stop being a refuge.

Their relationship becomes the space where creativity is reimagined. Niko listens to Merritt’s old songs and responds as a person, not as a consumer, which lets her remember that her music once meant connection rather than extraction.

The moment she plays guitar for him again carries emotional force because it happens in private, without performance pressure, and with the possibility of joy. Meanwhile, Merritt pushes Niko to donate a painting and to acknowledge his talent, not as a marketing strategy but as an invitation to step into his own worth.

His eventual recognition—one of his works appearing in a viral context—arrives almost by accident, suggesting that creative success can be an outcome without being the goal. The theme also highlights the difference between validation and meaning.

Merritt receives an email about collaboration that triggers old memories and trauma; the opportunity isn’t automatically good just because it signals career revival. What matters is consent and readiness.

By the end, the studio Niko builds for Merritt symbolizes a new contract with creativity: art made in a space shaped by love, safety, and mutual respect, rather than by pressure. Their creative lives become less about proving something to the world and more about telling the truth to themselves.

In that sense, creativity becomes an instrument of agency. It allows Merritt to reclaim her voice on her own timeline, and it allows Niko to step forward without losing the private core that made his art real in the first place.

Home, belonging, and the fear of being displaced

The question of where Merritt belongs is expressed through literal rooms, keys, renovations, and the uncomfortable reality that refuge can quietly become dependence. Merritt’s long stay in Olivia and Dev’s house begins as temporary, but time turns it into a soft limbo where she is protected from risk yet also protected from growth.

Olivia’s pregnancy forces that limbo to collapse, and Merritt experiences the demand to move as a rejection, even though it is also a natural life transition for a family expanding. The emotional charge comes from the imbalance of control: Olivia and Dev own the space, set the rules, and can repurpose Merritt’s room into an office without asking in a way that feels collaborative.

That dynamic brings up old sibling hierarchies—Olivia as the capable architect of a life, Merritt as the guest whose needs must be managed. Merritt’s own house, “The Mollusk,” is a physical representation of her stalled inner life: strange, half-abandoned, full of potential that feels impossible to access alone.

Renovation becomes more than carpentry; it becomes a rehearsal for taking up space without apology. Niko copying the keys is symbolically rich because it is about access and trust.

To let someone into your home is to admit you plan to stay, that you believe the place is worth maintaining. At the same time, Niko himself is facing displacement when his rental is converted into a vacation property, which frames housing insecurity as not only personal but systemic.

His imminent move intensifies the romance, but it also exposes how precarious “home” can be when it depends on markets and other people’s decisions. Their shared time in the rental house creates a temporary home that is emotionally real even if it has an expiration date, and the mural he leaves behind is an act of anchoring—proof that what they built mattered.

When Merritt later decides to fight for him, she is also fighting for a home that is chosen rather than assigned. The final vision of them living together in Crested Peak, surrounded by friends and family, does not suggest home is a perfect refuge; it suggests home is built through commitment, community, and the courage to stop living as if you might be asked to leave at any moment.

Love without rescue, and the discipline of mutual care

The romance between Merritt and Niko rejects the fantasy that love fixes damage, even as it insists that love can create conditions where healing is more possible. Merritt is drawn to Niko partly because he is steady and kind, and she worries that her intensity will consume him.

Olivia’s warning not to toy with him echoes a broader fear: that Merritt’s history makes her inherently unsafe to love. The story refuses that simplification.

Merritt does not become harmless; she becomes more honest. Niko does not become a savior; he becomes a partner who listens, sets boundaries, and stays present without turning her pain into his purpose.

Their decision to frame the relationship as temporary is a protective strategy for both of them, a way to enjoy closeness without promising what they fear they cannot sustain. But the feelings become real anyway, and the tension shifts from “should we” to “how do we do this responsibly.” The dissociation moment is crucial because it shows care as behavior, not sentiment.

Niko doesn’t make it about himself, and Merritt doesn’t pretend she’s fine to keep him. That exchange models intimacy that respects the body’s signals and the mind’s limits.

The theme also explores how love can challenge avoidance. Merritt tries to manage her feelings by texting Alan, reaching for a familiar, low-risk script of connection that doesn’t demand full presence.

Niko disrupts that pattern because he is physically and emotionally there, and he expects truth. Meanwhile, Niko’s own disclosures—about his family history and his bisexuality—show that he is not simply the stable caretaker; he is also someone with vulnerability and a desire to be fully known.

Their reunion sequence, with both traveling in opposite directions to reach each other, underscores the shift from passive longing to active choice. Love becomes a decision that includes logistics, difficult conversations, and the willingness to face consequences together.

By the end, the relationship is portrayed as grounded not in grand gestures but in shared work: building a studio, joining community life, making room for each other’s ambitions, and creating routines that support stability. The theme argues that mutual care is not romantic perfection; it is a practiced commitment to show up with honesty, patience, and respect—especially when old patterns threaten to take over.