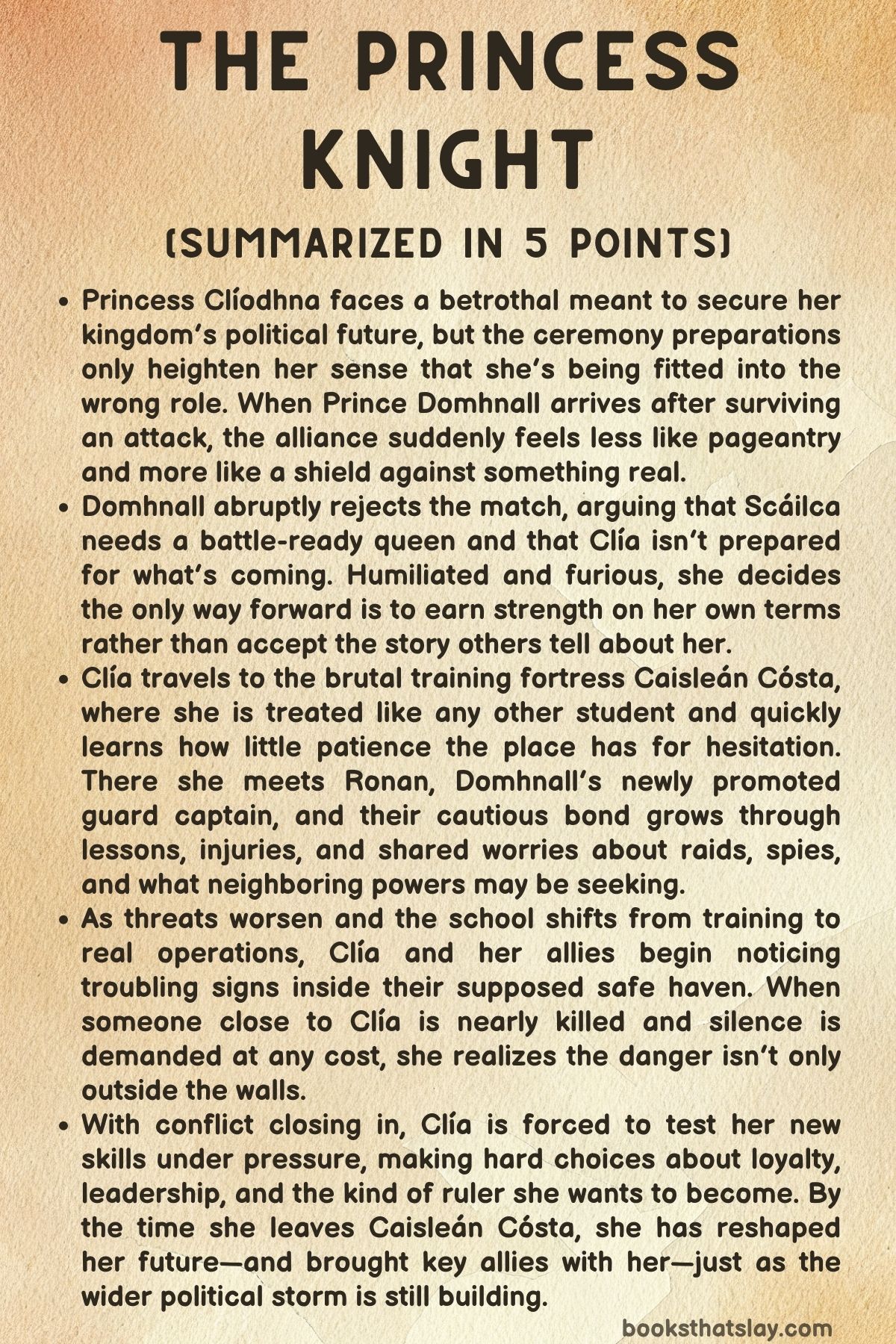

The Princess Knight Summary, Characters and Themes

The Princess Knight by Cait Jacobs is a fantasy coming-of-age story set among rival kingdoms, court expectations, and rising border threats. Princess Clíodhna of Álainndore is raised to be a diplomatic symbol—polished, obedient, and ready for a political marriage that will secure druidic favor.

But when war rumors turn real and her intended match rejects her as “too soft” for what’s coming, Clía chooses a different path. She leaves the safety of court to train at a harsh warrior stronghold, chasing a title she was never meant to claim—and discovering power, danger, and love where she least expected it.

Summary

Clíodhna keeps to her rooms while Álainndore prepares to welcome Prince Domhnall of Scáilca, the man she is expected to marry. The palace is busy with banners, feasts, and rituals, but Clía feels only pressure.

Even her betrothal gown feels wrong until she takes scissors to it and rebuilds it with her tailor, Sárait, shaping it into something that finally matches how she wants to stand in the world—careful, controlled, and “right.” Her mother, Queen Eithne, treats the marriage as sacred theatre: a public sign that Álainndore and Scáilca are united, pleasing both the gods and the Draoi whose blessings keep the land fertile. Clía agrees in public, but privately she worries that if anything goes off-script, she will be blamed.

Outside the palace polish, darker news circulates. Supplies go missing in northern villages, and there are rumors that Tinelann may be involved.

Clía overhears a report and is scolded for listening, but she cannot ignore the sense that something is shifting. Her closest comfort is Murphy, a young dobhar-chú she saved after warriors killed its parents.

Murphy’s steady loyalty makes Clía feel less alone in a court where every smile comes with conditions.

Across the sea, Ronan Ó Faoláin starts his first day as captain of Domhnall’s guard. He’s promoted after the previous captain is found dead, and his commander warns him that Ionróiran raids are rising.

Ronan carries old grief and chronic pain in his ankles, but he’s determined to prove he deserves the role. On the journey to Álainndore, he senses danger in the forest and stops the caravan just in time.

An ambush erupts, and Ronan fights hard to keep attackers from reaching the prince’s carriage. Domhnall kills one assailant; Ronan kills another at close range.

They survive, but the message is clear: the road itself is no longer safe.

Domhnall arrives at Álainndore with blood on Scáilcan armor and too few guards. In private, he tells Queen Eithne about the attack near the Hill of Tiarnas and warns that the Ionróirans may be working with Tinelann to sidestep treaties by using forces not bound by old agreements.

Eithne refuses to accept the possibility, but Domhnall insists the threat is spreading. He even plans to leave the next morning instead of staying for celebrations, which unsettles the court.

Eithne sends Clía to speak with Domhnall in the eastern courtyard, expecting them to perform closeness. Instead, Domhnall shocks her: he will not marry her.

He claims Scáilca needs a warrior-queen, someone who can stand at the front when war comes, and he says Clía is not that. Clía is furious—not only because the alliance is at risk, but because he reduces her to a “pretty face” after a lifetime of being trained to serve as a symbol.

Ronan witnesses enough of the exchange to understand how deeply it cuts.

A war council forms, and the bad news piles up. Álainndore’s Chief Barra is found dead in an alley.

Domhnall’s guard captain was killed days earlier. Domhnall urges scouting near the Diamhair Mountains to learn what Tinelann is doing, but Chief Ó Connor refuses permission, saying Álainndore won’t move unless directly attacked.

Clía senses Ó Connor is hiding how close the danger already is, but in the moment she stays silent—then hates herself for it.

Back in her rooms, Clía tears apart the dress meant for her betrothal, and she hears court whispers branding her weak. During a fidchell game with Ó Connor, she argues that waiting is foolish; he insists they’re prepared, yet his evasions confirm her suspicion that the kingdom is already bleeding at the edges.

When she learns Domhnall and Ronan will train at Caisleán Cósta under General Kordislaen, Clía makes a decision: if she’s going to be judged as too fragile to matter, she’ll change what she can control. She will train, earn the title of curadh, and force the world to see her differently.

In the sacred grove, the Draoi pressure the king and queen, hinting that Álainndore’s disunity could cost them magical support. After the Draoi leave, Eithne blames Clía for the broken betrothal.

Clía counters with a plan: she’ll go to Caisleán Cósta and return stronger, improving Álainndore’s standing when conflict arrives. Eithne finally agrees, warning her the training is brutal and that Clía’s motives will be questioned.

At Caisleán Cósta, Clía is treated like any other student—ignored at the carriage, given a tiny windowless room, marched into an arena where Kordislaen demands an immediate trial by duel to first blood. Paired against the fierce Niamh Morrigan, Clía tries to refuse, but refusal is not allowed.

She’s cut and humiliated, and Kordislaen orders her to put the weapon away and leave. Ronan arrives to begin his own training track and receives private praise from Kordislaen, along with a warning to keep quiet about any special help.

Ronan finds Clía alone in the library and tends her wound. Pressed, Clía admits she has something to prove.

Together they piece through unsettling possibilities: Tinelann may be searching for the lost Ríoghain’s Jewel, using raids as cover. Clía’s fear for Álainndore deepens, especially as letters home are restricted.

Domhnall confronts her at Caisleán and bluntly declares he will marry someone else for political reasons—Niamh—confirming that Clía was never his chosen future.

Clía is saved from being sent away when Ó Connor’s bargaining brings Sárait to the castle. Sárait steadies Clía, and Clía begins to rebuild herself the way she rebuilt that first gown: with patience, stubborn practice, and craft.

In hidden passages, Clía discovers rare silver cloth infused with iron by the Draoi—so tough it resists blades. She and Sárait quietly design a secret project, turning fashion skill into something meant for survival.

Training intensifies. On a Ghostwood mission, Clía is placed with Ronan, Domhnall, Niamh, Kían Horgan, and Commander Ó Dálaigh.

Ronan begins teaching her sword work early each morning, and study sessions turn into friendship and then into a bond neither of them planned. Ronan gives her a sword fitted with a pink crystal from her first mission; she names it Camhaoir, “Daybreak.” A kiss follows, witnessed by Niamh, and Clía pulls away, insisting duty must come first.

Still, the connection remains.

As raids worsen, dalta classes end and trainees are folded into real patrols and missions. Clía overhears secret orders about “handling” a security matter by dawn, adding to her suspicion that threats exist inside the walls as well as beyond them.

Then Sárait collapses with signs of poisoning. Kordislaen refuses help until Clía and Kían push back, and Ó Connor brings a healer who stabilizes her.

Clía realizes that speaking up makes enemies—but staying quiet costs people.

Soon after, the castle is attacked. Griffin locks Clía and Domhnall in a hidden storage space, but Murphy helps break them out.

Clía arms herself, retrieves Camhaoir, and joins the fight. In the chaos, Camhaoir’s gem glows, feeding her stamina with strange energy.

Underground tunnels collapse as defenders sacrifice ground to block invaders, and Clía finds Ronan alive but battered. Learning Kordislaen was seen heading toward the cliffs, Clía and Ronan race after him and discover the truth: Kordislaen is not simply harsh—he’s aligned with the enemy.

On the cliffs, Kordislaen taunts Ronan with memories of his mother’s death, then wounds Ronan’s sword arm. Domhnall and Niamh arrive as a ship packed with Ionróiran warriors nears a vulnerable tunnel entrance.

Ronan chooses to lead troops to defend the tunnel while Clía stays to finish Kordislaen. They exchange swords—Ronan takes Camhaoir to keep fighting, and Clía trusts her secret armor to keep her alive.

Ronan leads a brutal defense at the cliffside tunnel as Murphy attacks boats from the water. Domhnall is badly wounded, and their ally MacCraith dies saving him.

Meanwhile, Clía provokes Kordislaen into a direct duel, exploits his injured leg, and uses her armor and training to survive his strikes. She disarms him and kills him, and without his control the attackers break and retreat.

In the aftermath, the survivors rebuild and count the dead. Sárait recovers.

Domhnall prepares to return to marry Niamh, his face scarred and his future narrowed. Clía avoids Ronan for a time, frightened by how much she wants him and how dangerous that want feels.

But on the morning she leaves Caisleán Cósta, she goes to Ronan and speaks plainly. They agree the jewel’s power must remain secret.

Clía offers him a place beside her—not as Domhnall’s guard, but as Álainndore’s new chief of war.

Clía departs with Ronan and Murphy, leaving behind the court’s old story for her life. Months later, they rest by Álainndore’s palace lake, preparing to meet Ronan’s father and holding an invitation to Domhnall and Niamh’s wedding.

The alliance that began as a forced betrothal has shifted into something else: a partnership built on choice, training, and a readiness to face what’s coming.

Characters

Clíodhna (Clía)

Clía begins as someone trained to survive court life by controlling what she can: appearances, etiquette, and the promise that if everything is “perfect,” nothing will go wrong. Her fixation on remaking the betrothal gown is less vanity than a coping mechanism, a way to manufacture certainty when her future is being decided around her.

What makes her compelling is that she does not lose her softness to become formidable; she carries it into the battlefield. Her tenderness toward Murphy and her loyalty to Sárait show that her bravery is rooted in care, not conquest.

As training strips away privilege and protection, she is forced to confront how much of her fear comes from being told she is fragile, and how much comes from believing it. By choosing Caisleán Cósta and enduring humiliation, she reframes her identity from ceremonial heir to active protector, and her growth is marked by repeated decisions to act even when she is terrified.

The shimmering fabric she becomes obsessed with is an extension of her arc: she turns “women’s work” into literal armor, proving that craft can be as strategic as a sword. When she finally kills Kordislaen, it is not a loss of innocence so much as a claim of authority—she stops asking permission to be strong and becomes the person who sets the terms.

Prince Domhnall of Scáilca

Domhnall is a prince shaped by looming catastrophe, the kind of leader who treats relationships as pieces on a board and then is surprised when people bleed. His refusal to marry Clía is a political calculation delivered with cruelty, and the cruelty matters: it exposes how easily he reduces someone he cares about into an “asset” that failed to meet requirements.

At the same time, Domhnall is not simply heartless; he carries an honest dread about what is coming and behaves like someone trying to outrun grief by preemptively hardening himself. His dynamic with Ronan reveals his worst habit—using promises as leverage—and his later confrontation with consequences suggests he is capable of self-awareness, even if he does not always choose better.

His engagement to Niamh reads as the version of kingship he thinks he must embody: a union built for war readiness. The injury he sustains in the battle mirrors his moral and emotional scars—his world is not cleanly controllable, and he cannot “policy” his way out of pain.

By the end, his gestures toward Clía and Ronan feel like a reluctant admission that he misjudged them, and that leadership without respect becomes isolation.

Ronan Ó Faoláin

Ronan is the story’s quiet engine: disciplined, observant, and haunted. His chronic ankle pain and childhood trauma are not decorative backstory; they define how he moves through power structures, always proving, always bracing for loss.

He is promoted into responsibility in the shadow of death, and that pattern follows him—he keeps surviving while people around him pay the price. Ronan’s competence is paired with a deeply protective instinct, which becomes most visible in small, intimate actions: cleaning Clía’s wound, making her a sword, offering steadiness without demanding control.

He is also vulnerable to manipulation because he wants belonging so badly, and Domhnall exploits that longing with the promise of Caisleán Cósta. Ronan’s bond with Camhaoir and the strange power he feels while wielding it adds a second layer to his arc: he is not only learning to fight, he is learning to lead while carrying something dangerous and secret.

Choosing to leave Scáilca’s service to become Álainndore’s chief of war is his most radical act of self-definition—he stops being an extension of a prince’s needs and becomes a partner in a shared mission, even while knowing that love and duty will keep testing each other.

Queen Eithne

Eithne is the embodiment of statecraft as performance. She treats alliance-making like ritual theater—decorations, toasts, and divine symbolism are tools to stabilize a fragile political ecosystem.

Her reliance on the story of Tara and Ríoghain is not merely faith; it is propaganda with sacred language, designed to keep nobles compliant and the Draoi appeased. As a mother, she is harsh in a way that feels both strategic and personal: she blames Clía for outcomes Eithne herself engineered, because admitting miscalculation would weaken her authority.

Yet she is not indifferent to survival; she makes decisions under pressure and ultimately supports Clía’s training because she can be convinced by advantage. Eithne’s most revealing trait is that she confuses control with safety, and her parenting becomes an extension of governance—Clía is treated as a diplomatic instrument until Clía forces her to recognize the daughter underneath.

Chief Ó Connor

Ó Connor is mentor, strategist, and gatekeeper rolled into one, and he is often the only adult who treats Clía like a person instead of a symbol. His banter and the fidchell games are not trivial; they are how he teaches her to think in moves and countermoves when everyone else expects her to smile and obey.

At the same time, he is a man of secrets, withholding information about threats on Álainndore’s shores and refusing to commit support to Scáilca unless forced. That refusal is not simple cowardice; it suggests a belief that premature action could destabilize Álainndore internally, or expose vulnerabilities he cannot admit.

His willingness to pull strings with Kordislaen and send Sárait to Caisleán shows how he operates—relationships are his weapons. The most important shift in his role is that he becomes less a protector and more a catalyst: by nudging Clía toward offense, he helps create a future leader who will not wait for permission to defend her people.

Sárait

Sárait begins as a tailor delivering a gown and quickly becomes one of the story’s strongest quiet forces. She understands Clía’s need for control without mocking it, and the act of remaking the dress becomes their first shared act of rebellion against a destiny pre-stitched by others.

At Caisleán, Sárait serves as a lifeline to home and a reminder that dignity can be crafted, not granted. Her guidance is practical, affectionate, and relentless: she pushes Clía to keep going when Clía wants to collapse.

The hidden fabric room and the enchanted silver cloth connect Sárait to a deeper undercurrent of the world, where craft, Draoi power, and warfare intersect. Her poisoning attempt is a turning point because it proves that the conflict is not only at borders; it is inside institutions, among “allies,” and within the castle walls.

Surviving makes her more than a helper—she becomes living evidence that resistance is necessary, and that the enemy can reach anyone.

Murphy

Murphy is more than a companion animal; he is Clía’s moral anchor. Rescued after violence, he embodies what war destroys and what Clía refuses to become numb to.

His presence repeatedly collapses the boundary between “court problems” and real stakes, because he is a constant reminder of innocent casualties. When he saves Clía and Domhnall from confinement and later attacks boats in battle, he transforms from symbol of tenderness into active protector, mirroring Clía’s own evolution.

Murphy’s loyalty also highlights a theme the human characters struggle with: devotion without politics. He chooses Clía simply because she saved him, and that purity throws the court’s transactional relationships into sharper relief.

General Kordislaen

Kordislaen is the story’s clearest embodiment of power without conscience. He presents brutality as meritocracy, using fear to control trainees and filtering out those who do not already fit his definition of “worthy.” His interest in secrecy, his cold response to Sárait’s collapse, and the ominous orders Clía overhears all paint him as someone who treats people as expendable tools in a larger game.

He is also personally cruel, targeting Ronan’s trauma to destabilize him at a critical moment, which reveals that he understands psychology and enjoys using it. Kordislaen’s pristine appearance while others bleed marks him as a predator rather than a protector—he watches war like a stage he believes he owns.

His death at Clía’s hands is not just vengeance; it is the narrative severing of a corrupt lineage of martial authority, making space for a new kind of leadership built from responsibility rather than domination.

Draoi Griffin

Griffin functions like an institutional mask: polite, authoritative, and unsettlingly willing to enforce secrecy. He ushers students into the system, explains the rules, and then participates in morally questionable containment by locking Clía and Domhnall away when the castle erupts into chaos.

Whether his motives are obedience, fear, or complicity, the effect is the same—he demonstrates how “neutral” bureaucratic power becomes dangerous during crises. His later strategic discussions also show the Draoi perspective: measured, resource-conscious, and often more concerned with long-term stability than individual suffering.

Draoi Ruairc

Ruairc represents external spiritual pressure turned political leverage. He does not merely advise; he threatens withdrawal of druidic support, making it clear that the gods and the Draoi are power blocs, not distant mysticism.

His presence forces Álainndore’s rulers to confront how precarious their standing is, especially when neighboring lands suffer from diminished druidic favor. In narrative terms, he is the voice that makes “unity” feel less like an ideal and more like coercion.

Commander Derval

Derval is a disciplined professional who frames the stakes early: the guard’s duty is not abstract honor, it is survival under rising raids. Her warning to Ronan about mistakes shows the culture of Scáilca’s military—results matter, and failure has immediate consequences.

Even with limited page presence, she reinforces how high the pressure is on Ronan and how little room he has to be anything but excellent.

Grúgán

Grúgán’s death is a shadow that hangs over Ronan’s promotion. He signals that the danger is not limited to battlefield ambushes; it can reach inside hierarchies and remove key people quietly.

Even as an offstage figure, he raises the possibility of intrigue, infiltration, or targeted elimination, setting a tone of mistrust.

Chief Barra

Barra’s sudden death in an alley is an alarm bell for Álainndore’s complacency. He is evidence that the conflict has already arrived, regardless of what leaders want to believe.

His murder also functions as narrative pressure on Clía—she recognizes that denial is no longer safe, and that hidden rot inside the realm can be as fatal as foreign invasion.

Niamh Morrigan

Niamh enters as an obstacle: powerful, aggressive, and positioned as the kind of warrior Domhnall claims he needs. Her early dominance over Clía in the trial reinforces the story’s initial hierarchy of strength.

What makes her interesting is that she does not remain a flat rival. She recognizes Clía’s courage when Clía defends Sárait, and later she acts decisively during battle, taking command and forcing Ronan forward when hesitation could doom others.

She also carries her own vulnerability under the armor—Domhnall’s fear for her safety reveals that she is not simply a political pick, she is someone with real stakes. Niamh ultimately represents a parallel path for womanhood in war: she fits the old definition of formidable, but she is capable of respect and alliance once Clía proves herself on her own terms.

Kían Horgan

Kían is the charm of the noble class with a conscience, and his warmth serves as social glue in a tense group. He provides observations about suspicious activity and helps keep attention on real threats instead of court drama.

His grief for MacCraith and his decision to remain in the north show a deeper commitment than performative bravery; he chooses ongoing service over comfort. Kían’s role is also relational—he bridges factions, supports Clía and Sárait, and acts as a messenger figure who understands that information can be as valuable as steel.

Commander Ó Dálaigh

Ó Dálaigh’s presence on the Ghostwood mission adds a stabilizing layer of command. He represents the professional backbone of Caisleán’s operations: planning, logistics, and the expectation that trainees will face real danger quickly.

Even without a personal arc, he shapes the environment that forces the younger characters to mature fast.

MacCraith

MacCraith is the story’s reminder that valor often ends in quiet tragedy. He returns with additional warriors after delivering a plea for aid, and his death—stabbed from behind after saving Domhnall—captures the unfairness of war: heroism does not guarantee survival, and the most loyal people can be removed in an instant.

His loss lands heavily because it is not symbolic; it is practical damage to morale, leadership, and the future.

Tara and Ríoghain

These divine lovers operate as living mythology in the political sphere. Eithne uses their story to frame the marriage as sacred reenactment, turning romance into public ritual meant to reassure gods and Druids alike.

For Clía, the myth becomes something to outgrow: she refuses to remain a symbol in someone else’s legend and instead starts writing her own, one defined by earned strength rather than divine costume.

Tinelann

Tinelann is the political specter behind the violence, the possible mastermind leveraging loopholes and proxies to bypass treaties and destabilize rivals. Even when not physically present, the suspicion around Tinelann drives strategy, paranoia, and urgent preparation.

The idea that they may be searching for Ríoghain’s Jewel adds a layer of ambition beyond conquest, suggesting a conflict that is as much about power sources and mythic artifacts as it is about territory.

Themes

Control, Perfection, and the Anxiety of Ceremony

Silence, fabric, and exact measurements become Clíodhna’s first language for coping with a life that keeps being decided in rooms where she is expected to smile. The wedding gown episode is not just a prelude about clothing; it exposes how perfectionism can function like armor when someone feels cornered by expectations.

She cannot accept any alternative dress because the problem is never really the hemline or the beadwork. The problem is that the entire event is built to reassure other people: her mother’s political plans, the court’s appetite for spectacle, and even the religious narrative Queen Eithne wants to reenact for the Draoi.

Clía’s insistence on remaking the gown until it feels “right” shows a desperate search for a single domain where her preferences carry real weight. The calm she experiences once the dress finally fits is temporary relief, the kind that comes from making one piece of the world obey.

It also foreshadows how quickly that relief collapses when Domhnall refuses the betrothal and the court rewrites her story as weakness. In that moment, perfection is revealed as a bargain that was never guaranteed: she can do everything “correctly” and still be humiliated.

This theme evolves when Clía carries the same instinct into training. At Caisleán Cósta, there is no ceremony she can control, no tailor’s quiet collaboration, and no private room that feels safe.

The institution’s cruelty forces her to confront a hard truth: control based on appearances is brittle, and control grounded in capability is slow, painful, and public. Her shift from obsessing over a perfect day to designing practical clothing and covert armor is a shift from perfection as performance to competence as survival.

Even then, the story keeps testing whether control is ever fully available to her. Letters are monitored, secrets are policed, and violence interrupts schedules.

Clía’s growth does not eliminate anxiety; it changes what she does with it. She stops trying to make life flawless and starts trying to make herself ready, accepting that readiness is not a guarantee of comfort, only a refusal to be helpless.

Identity Under Scrutiny and the Demand to Earn Authority

Clía begins as someone whose identity is treated as a title rather than a self. She is “supposed to be” a future queen, “supposed to be” agreeable, and “supposed to be” a symbol that confirms alliances.

Domhnall’s rejection is brutal because it turns that symbolic identity into an insult, reducing her to decoration and declaring her unfit for a harsher world. That humiliation is not simply romantic rejection; it is a political and personal demotion delivered in private but designed to echo publicly.

The whispers in the castle afterward show how quickly a court can turn a woman’s interior life into gossip and how easily “strength” is defined by others as something she either naturally has or does not. The accusation of weakness becomes a trap: if she protests, she is emotional; if she accepts it, she confirms it.

The narrative uses this pressure to show identity as contested territory rather than a stable trait.

Training reframes identity as something built through repeated choices. At Caisleán Cósta, Clía is treated like any other dalta, stripped of deference, and forced to confront the gap between how she has been presented and what she can actually do.

The early duel, where she is injured and dismissed, is a public attempt to freeze her identity in failure. What changes her trajectory is not a sudden revelation of hidden talent but her refusal to leave.

She keeps showing up, keeps learning, and keeps taking on responsibilities that are not glamorous. Over time, identity becomes less about being recognized and more about acting consistently under pressure: defending Sárait when it is risky, demanding honesty about threats, choosing to fight during the siege, and refusing to let others decide what she is allowed to be.

The curadh pin matters because it is an institutional recognition, but the deeper shift is that she stops needing permission to consider herself capable.

The theme also complicates what “authority” should look like. Clía’s mother wants authority that reassures elites and the Draoi; Domhnall wants authority that intimidates enemies; Kordislaen wants authority that crushes students into obedience.

Clía gradually forms a different model: authority that protects, that prepares, and that tells the truth even when truth is inconvenient. Her final choice to bring Ronan with her and elevate him as Álainndore’s chief of war signals a leadership identity rooted in partnership and competence, not bloodline alone.

Identity becomes something she claims, demonstrates, and shares rather than something the court grants and then withdraws.

Political Marriage, Sacred Legitimacy, and the Machinery of Alliance

The betrothal in The Princess Knight is engineered like a public ritual designed to stabilize the world, not a personal decision. Queen Eithne’s planning frames marriage as a strategic response to failing harvests, shifting seas, and the Draoi’s influence, which turns romance into an economic and spiritual instrument.

The story shows how political systems often rely on pageantry to disguise coercion: a staged welcome, a private walk meant to produce the right impression, and a mythic story about divine lovers used to make human bargaining seem holy. This does more than pressure Clía; it reveals the kind of governance Álainndore practices, where legitimacy is borrowed from religious symbolism and maintained through appearances of unity.

When the Draoi later pressures the king and queen, the threat is not merely disapproval but withdrawal of support that affects land and livelihood. The sacred is not separate from politics; it is one of its enforcement tools.

Domhnall’s refusal also exposes the cruelty of alliance-making. He does not say the match fails because of diplomatic complications; he says Clía herself is insufficient, making her body and reputation the negotiable currency.

His pivot toward marrying Niamh underscores how quickly individuals can be swapped when marriage is treated as strategy. Yet the narrative refuses a simplistic condemnation of politics.

There are real threats, raids, and deaths; alliances might be necessary. The question becomes what kind of political system is being protected and who it sacrifices.

Álainndore’s leadership clings to denial and ritual; Scáilca’s leadership pushes for preparedness and intelligence. Both approaches contain self-interest, and the people caught between them are expected to bear the cost.

This theme deepens during the siege and the aftermath. Once violence arrives at the gates, ceremony is irrelevant, and the legitimacy that mattered yesterday is replaced by the immediate need to hold walls, defend tunnels, and treat the wounded.

The story suggests that political marriage is often advertised as protection but can become a distraction from building real protective capacity. Clía’s decision to train, then to return with Ronan as a military leader, is a different kind of alliance: not a symbolic union meant to impress the Draoi, but a practical coalition grounded in shared knowledge and shared risk.

The invitation to Domhnall and Niamh’s wedding at the end lingers like a reminder that politics continues, but the meaning of marriage has shifted for Clía. She has seen what the machinery demands and has started carving out a version of alliance that does not require her to be reduced to an emblem.

Denial, Preparedness, and the Cost of Waiting for Proof

Warnings arrive early: stolen supplies, rumors of involvement from Tinelann, the death of a guard captain, and an ambush near Tiarnas. The story uses these signals to contrast two instincts in leadership: insistence on certainty and insistence on readiness.

Chief Ó Connor’s refusal to authorize support unless Álainndore is directly attacked represents a familiar political posture—avoid commitment, avoid provoking conflict, and preserve the image of calm. Domhnall’s frustration represents the opposite posture: treat early signals as meaningful, assume adversaries are already adapting, and act before choices narrow.

The narrative shows how denial can masquerade as prudence. Ó Connor claims readiness, yet he dismisses reports, hides details, and blocks communication with the monarchs.

His stance is not neutral; it is a decision to keep the kingdom’s posture unchanged, even as deaths and raids suggest the posture is already outdated.

Clía’s evolution tracks the emotional cost of waiting for proof. At first, she is consumed by her own fear of personal failure, but denial in her environment forces her to broaden that fear into political dread.

She senses that danger has already reached their shores, not because she has official intelligence, but because the patterns are visible: missing supplies, sudden deaths, evasive answers, and the court’s desperate focus on keeping a betrothal narrative intact. The narrative makes clear that “waiting until attacked” is not a clean threshold.

People die before the line is officially crossed; communities are tested, not kingdoms. By the time the siege happens, the cost of delay has already been paid in bodies, poisoned allies, and compromised tunnels.

Preparedness is not portrayed as paranoia; it is portrayed as responsibility that is emotionally difficult because it requires acting on uncertainty. Scouting, training, reinforcing defenses, and sharing intelligence all involve admitting vulnerability.

The story also critiques preparedness when it is centralized under unaccountable power, as seen in Kordislaen’s secrecy and threats. Still, the central argument remains: leaders who demand perfect certainty tend to outsource risk to ordinary people.

Clía’s final role, traveling back with Ronan to shape Álainndore’s defense, is a commitment to preparedness as a form of care—choosing to face ugly possibilities early so fewer people are forced to face them alone later. The theme leaves an uneasy aftertaste: even after victory, threats remain, and the temptation to pretend things are stable will return.

The story’s insistence is that stability built on refusal to see is not stability at all.

Trauma, Chronic Pain, and the Quiet Ways Survival Reshapes a Person

Ronan’s body carries history in a way that cannot be hidden by rank or competence. His ankle pain is not a decorative detail; it is a constant reminder that heroism has a physical price that continues long after a fight ends.

The narrative treats trauma as something that persists in muscle memory, in flinches, in exhaustion, and in self-blame. Ronan’s recollections of his mother’s death and the moment he was saved form the emotional foundation of his drive to protect Domhnall and later to protect Clía.

He is not simply brave; he is vigilant, shaped by an early lesson that safety can vanish in seconds. That vigilance becomes both strength and burden.

It makes him effective in ambushes and battles, but it also traps him in a mindset where he is always responsible for outcomes he cannot fully control. His guilt is a form of loyalty to the past, an attempt to keep his mother’s death from becoming “just something that happened.”

Clía’s trauma is different in texture but similarly persistent. She experiences the violence of reduction—being publicly framed as weak, privately insulted, and socially erased into rumor.

Later, she experiences direct violence in the duel, the poisoning of Sárait, and the siege itself. The story shows how trauma can be social and psychological before it becomes physical.

Her initial response is to retreat, to tear apart the dress, to isolate. Over time, she learns to translate pain into purpose without denying that it hurts.

That translation is not always healthy; her insistence on duty sometimes functions as a way to avoid vulnerability, especially in her relationship with Ronan. When she apologizes for wanting something personal, it reveals how trauma can convince someone that desire is dangerous and that connection is a liability.

The magical surge linked to Camhaoir and the glowing crystal adds another layer. Power arrives not as pure empowerment but as something unsettling, something that changes what the body can do in crisis.

Ronan’s feeling of strange energy while wielding the sword suggests that strength can be borrowed from forces that demand secrecy and carry unknown costs. Trauma and power are both depicted as things that can transform a person in ways they might not fully choose.

Survival, in this story, does not restore anyone to who they were. It produces new versions of them—more capable, more wary, sometimes harder, sometimes tender in unexpected moments.

The tenderness matters: Ronan bandaging Clía, the gift of the sword, Clía’s grief over MacCraith, and her insistence on saving Sárait. These acts argue that survival is not only endurance; it is the ongoing decision not to let pain make you cruel.

Institutions, Mentorship, and the Abuse Hidden Behind “Making the Best”

Caisleán Cósta presents training as a gatekeeping system that claims legitimacy through brutality. Kordislaen’s opening speech and immediate demand for blood frame violence as a measure of worth, and his public shaming of Clía attempts to define her future in front of peers.

The institution’s structure encourages students to accept humiliation as normal and to treat compassion as weakness. This theme matters because it contrasts sharply with what Clía actually needs to become competent.

She needs instruction, repetition, feedback, and trust. Instead, she is thrown into a trial designed to produce spectacle and hierarchy.

The narrative is clear that this approach does not only test students; it selects for those willing to harm others, to accept harm silently, or to thrive in fear. “Only the best” becomes a slogan that excuses cruelty and allows leaders to frame any resistance as proof of unfitness.

Mentorship appears in two opposing forms. Ronan becomes the model of supportive mentorship: he teaches Clía, offers practical help, speaks honestly, and respects her agency even when he disagrees.

Ó Connor also acts as a mentor, but in a politically complicated way—he nudges her toward offense and uses relationships to open doors, yet he also hides information and tries to manage outcomes. Sárait mentors Clía through craft, reminding her that competence can be built and that time is not over simply because the court has decided a narrative.

Against these, Kordislaen represents mentorship as ownership. His private instructions to Ronan to keep quiet about special assistance, his threats about secrecy, and his refusal to treat Sárait show a leader who hoards control.

When he is later revealed as a direct threat, it confirms what his training style already suggested: the institution’s brutality was not neutral rigor but a method for consolidating power and loyalty through fear.

The theme culminates in the realization that institutions often demand vows and silence under the banner of security. Clía overhearing an order to “handle” a matter by dawn hints at a culture where problems are removed rather than addressed.

That atmosphere makes poisoning plausible and makes truth dangerous. The story’s critique is not that discipline is unnecessary, but that discipline without accountability becomes a weapon.

By the end, Clía’s growth involves choosing which mentors to trust and which institutional rules to challenge. She learns to respect training while refusing the idea that suffering is the only teacher.

The future she starts building with Ronan suggests an alternative: leadership that demands excellence while still treating people as people, not as disposable proof of a system’s toughness.

Secrecy, Information Control, and the Weaponization of Silence

Rumors, restricted letters, and blocked audiences reveal a world where information is treated like contraband. Early on, Clía’s eavesdropping is framed as misbehavior, and the reprimand she receives signals a hierarchy where knowledge belongs to officials, not heirs.

Yet the narrative repeatedly shows that withholding information creates vulnerability. Ó Connor’s insistence that Álainndore will not act until attacked is paired with his evasiveness about missing supplies and a chief’s death.

The royal court’s focus on presenting unity to the Draoi requires suppressing doubts, which turns silence into a tool for maintaining appearances. Domhnall’s warnings about treaties being bypassed show how adversaries exploit gaps created by formal rules.

If enemies can adapt, then leaders who refuse to share intelligence are not cautious; they are slow.

At Caisleán Cósta, secrecy becomes institutional policy. Kordislaen’s threat that nothing may leave the castle, not even in letters, is framed as security, but it also creates the perfect environment for internal wrongdoing.

When Clía later overhears a superior ordering a subordinate to “handle” something quietly, it confirms that secrecy can protect the wrong people. The poisoning of Sárait becomes a case study in how silence enables harm: if resources are withheld, if questions are discouraged, and if reputations matter more than truth, then an ally can be targeted with limited consequence.

Clía’s decision to resist publicly, alongside Kían and Ó Connor’s healer, is a refusal to accept the institution’s preferred silence.

The theme also extends to magical artifacts and power. The suspicion that Tinelann is searching for Ríoghain’s Jewel and the later agreement that the jewel must remain secret show how knowledge can be existentially dangerous.

Clía and Ronan are forced to make adult decisions about what truths can be shared, with whom, and when. Secrecy becomes morally ambiguous: sometimes it is protection, sometimes it is control, sometimes it is cowardice.

The story’s tension lies in distinguishing these. Domhnall’s deflections about what “must be done” suggest secrets used to manage people’s emotions and choices.

Ronan being told to hide special assistance suggests secrets used to preserve a leader’s image of fairness. Clía and Ronan hiding the jewel suggests secrecy used to prevent exploitation and larger conflict.

By the end, the narrative does not romanticize transparency; it insists on discernment. Silence is never neutral, and the theme asks the reader to judge silence by its effects: does it protect the vulnerable, or does it protect power?

Love, Loyalty, and Partnership Chosen in the Shadow of Duty

Affection in The Princess Knight is always pressured by politics. Clía’s early attachment to Domhnall is intertwined with years of expectation, making it difficult to separate genuine feeling from the comfort of a familiar script.

When Domhnall ends the betrothal, his words attempt to erase not only romance but dignity, and that forces Clía to confront how often “love” in her world is conditional on usefulness. Her later calm when he announces his betrothal to Niamh is a turning point: it is not numbness, but release from chasing approval from someone who measured her by an image he wanted.

That release creates space for a different kind of connection to develop.

Clía and Ronan’s relationship grows out of shared work, shared truth, and mutual care rather than court performance. He helps her after she is injured, teaches her without belittling her, and respects her choice to prioritize duty even when it hurts him.

Their kisses are charged not just with desire but with fear—fear of gossip, fear of consequences, fear that softness will be punished in a world that rewards hardness. Clía’s insistence that she “can’t afford” personal entanglement reveals how duty can become a shield against vulnerability.

Ronan’s decision to pull back after the first kiss shows a moral discipline that contrasts with Domhn importing his needs onto others. Still, the story does not treat restraint as purity; it treats it as painful realism, and it shows how people can use duty to avoid confronting what they want.

The siege changes the stakes. When death is immediate, the idea that love is a distraction becomes harder to maintain.

Their night together before the mission is not escapism; it is a human claim to life in the face of probable loss. Afterward, the narrative tests whether partnership can survive when choices become tactical.

Ronan leaving Clía on the cliffs to defend the tunnel is both love and duty expressed through separation: trust that she can finish what must be finished, and acceptance that protecting many may require risking the one. The final decision—Ronan accepting her offer to become Álainndore’s chief of war and traveling with her—redefines partnership as shared leadership.

Love is not framed as a reward after victory; it is framed as a strategic and emotional alliance built on respect. In the closing scene by the lake, the cane that conceals a sword captures the story’s final claim: tenderness and readiness can coexist, and the most sustaining loyalty is the kind chosen freely, not assigned by a throne room plan.